Artfully Capturing Comedy: Will & Grace

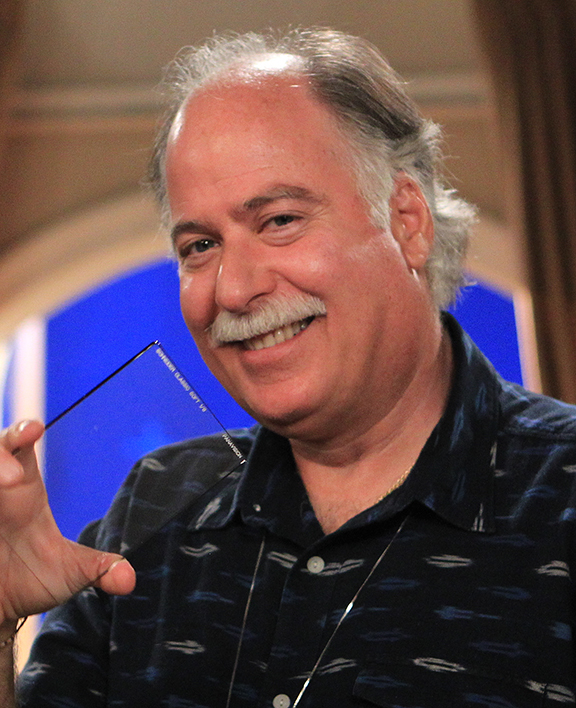

Emmy-winning cinematographer Gary Baum, ASC discusses his multi-camera lighting approach on the long-running series.

Emmy-winning cinematographer Gary Baum, ASC discusses his multi-camera lighting approach on the long-running series.

At this year’s Primetime Emmys, Gary Baum, ASC was honored with Outstanding Cinematography for a Multi-Camera Series for the “A Gay Olde Christmas” episode of Will & Grace. Baum spoke with American Cinematographerabout his work on that episode, his workflow and technology choices for multi-camera shows, and his philosophy of lighting.

The winning episode begins as the show’s characters visit the Tenement Museum in Manhattan and, as they take a tour, are transported back in time to New York City of 1911. “The script was conceived and written as a period piece,” Baum explains. “We had built all new sets: a museum lobby, a tenement, an upscale townhouse and an exterior.”

Set decoration was meticulously recreated, and Baum also worked with production design on the paint scheme. The show runners initially wanted the period piece section to be sepia-toned; Baum researched turn-of-the-century photographs of Jacob Riis and Lewis Hine, and shot some tests. “Then I had my colorist, Craig Budrick, pull back on the saturation, and I experimented with different filtration,” he says.

Baum and the team showed four different versions, and everyone agreed that the Steadicam shot moving from the current day museum lobby into the tenement exhibit would dissolve from the established look to black-and-white, and then to pastel colors in different degrees of desaturation, depending on the set.

With his gaffer Ben Zura and key grip Alfie Cunningham, Baum was able to achieve a softer lighting approach. “To emulate the vintage look, we used a covered wagon — silk over our bounce — and had some of the individual light units wrapped with diffusion, rather than placed closer to the Fresnel,” he says. “I also used a slightly different filter for each set, to complement the set design and wardrobe. I used Schneider Classic Softs in various strengths; I think I doubled up on one of the sets with a number 1 and a ½.”

The production originally planned to shoot the exterior street on the Universal backlot but, ultimately, the brownstones and street were built on stage. “Adding snowfall presented another challenge,” says Baum. “The scene was written for night, but I suggested it could be dusk, so we could add soft bluish hue that would contrast with the falling snow. We achieved that by adding two small LED space lights at 5K temperature, bouncing with equivalent Kelvin through the covered wagon.” The key lights were at approximately 2,950K, he continues. “We kept the singles and two-shots as long as possible on the lens, with a stop of T3.5,” he says. “Extremely well written and brilliantly acted, it was a very special visual episode that we don’t always have the opportunity to create.”

Baum has the history to prove it: he started working on Will & Grace in 2005, in the show’s first incarnation. “We are basically shooting a Broadway-style theatrical show in front of an audience,” he explains. “The audience’s experience, participation and interaction with the cast are what makes the performance come alive. In that respect, capturing scenes within the show without interruption is essential to the process.”

In 2005, Baum shot on Eastman 5294 400T 35mm film with Panaflexes, with exposureset for 400 ASA. “I had to light with a key of about 25 to 30 foot-candles to achieve an F3.2,” he says. “Now, with the Will & Grace reboot [in 2017], we wanted the show to look like the [original] Will & Grace, but cognizant that HD capture meant we’d have to work on it.”

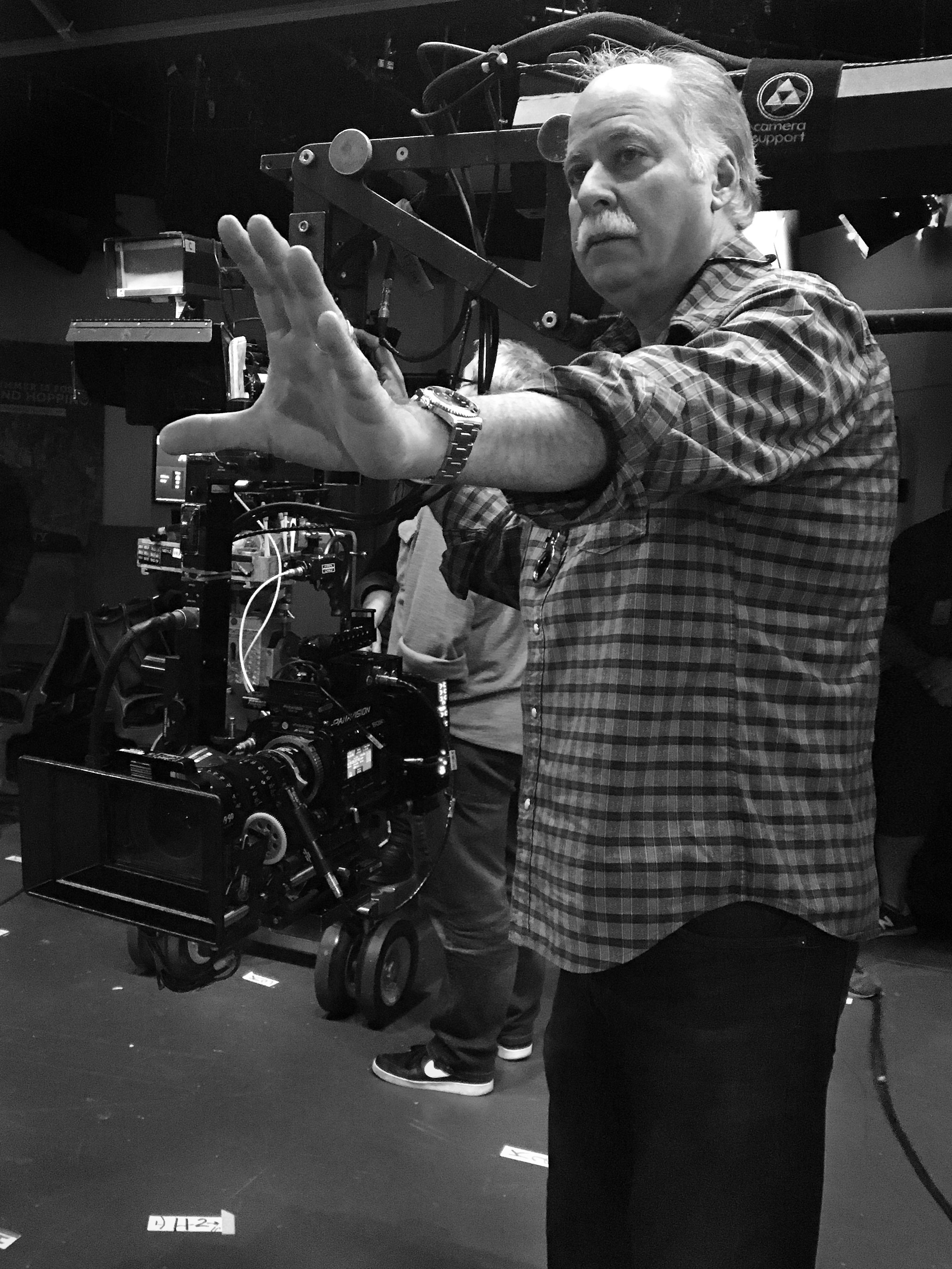

“Cameras are constantly moving about on the stage floor capturing their rehearsed shots. In essence, the audience is watching a theatrical style performance with a four-camera ballet.”

Baum currently shoots with Sony PMW-F55s, exposing at an effective range of about 1200 ASA. “I’m still using the same Panavision Primo [11:1 zoom] lenses that we used 20 years ago, but now I can key at about 14 foot-candles, achieving a stop of F4,” he says. “Key-to-fill ratio is equivalent as is contrast to brightness. However, we’re not using fewer lighting units, just less intensity.” He adds that he’s “always testing new and improved filtration in order to keep the film cinematic look. My approach to cinematography is essentially the same. I light to a specific stop, using a light meter for reference, but I’m more aware of the constantly changing lighting options available, most notably, LEDs that we carry for Obie lights and close-quarter capture.”

On Will & Grace, Baum uses four cameras on dollies, each of which has specific assignments on a per-scene basis. “Cameras are constantly moving about on the stage floor capturing their rehearsed shots,” he says. “In essence, the audience is watching a theatrical style performance with a four-camera ballet.”

Baum can’t light from the floor because of that same constant camera movement. “We also don’t have the luxury of multiple lighting set-ups within a scene,” he explains. “When we light for a specific set, we have to accommodate for four cameras with multiple angles, sometimes 40 per scene. We try to achieve and maintain a single-camera cinematic look while not interfering with the script or the energy that is live-audience specific.”

Growing up in New York, Baum’s attraction to working in motion pictures began when he was in high school. Although he was taking photography and cinema classes, what sealed the deal was when he exited the subway on the way to class and saw Owen Roizman, ASC and his crew shooting what would become the famous chase scene in The French Connection (1971). “Two days later, I was still out there with my friends, watching,” he recalls. “We were in awe of everything. It was a great learning experience. At that point, I decided, this is what I want to do.”

After relocating to Los Angeles and his first year of college, Baum got a job at Panavision working with the electronics department, and then got a job as a film loader at Lorimar on the MGM studio lot. At the same time, he continued his education at UCLA, studying writing, cinema and theory classes. “I had a writing class with Nat Perrin, who used to write for the Marx Brothers,” says Baum. “He introduced me to [four-time Oscar winner] Joe Ruttenberg, ASC by asking me to take him home. He was very encouraging.”

“We’re making comedy. You can laugh all day long, which we did, and have a close working relationship with everyone. I found it — and still find it — to be a very uplifting experience.”

The writing class, Baum adds, was “just part of the curriculum. I was always more visual and was doing a lot of still work. I found writing interesting but it didn’t change my mind [about my career path]. It added another dimension to the crafting of a film or TV show.”

Baum says that Charlie Correll, ASC gave him his first chance out of the loading room. “I also worked with Bob Caramico [ASC] on Dallas, with William Gereghty on MacGyver, as well as The A-Team, in the 1980s,” he says. “It was an interesting time.” He also had a chance to assist 2nd unit on features including Heart Like a Wheel, Die Hard 2 and then Ghost Dad. He next got a job with John C. Flinn III, ASC on Magnum P.I. and then Jake and the Fatman.

On a day call on the series Step by Step, Baum met series cinematographer Tony Askins, ASC. “I’d never assisted on a multi-camera show before,” he says. “Tony asked me if I could stay on until the next week, and then asked if I wanted to finish the season. And I never really left.” Baum moved up to first unit operator on the show and got into the swing of the multi-camera show. “I was used to doing one shot at a time,” he says. “Here, I had to manage seven or eight different scenes, with 10 or 12 different focuses and lens size changes per scene. I had to retain information over a period of a couple of days, managing every scene. It was a very disciplined approach to the art of pulling focus, and I learned how to do it.”

Multi-camera clicked for Baum for other reasons as well, he says. “We’re making comedy,” he says. “You can laugh all day long, which we did, and have a close working relationship with everyone. I found it — and still find it — to be a very uplifting experience.”

When Askins moved on to shoot the pilot and first season of Will & Grace in 1998, Baum came with him as an operator, and those early days of working on the show were key to his growth as a cinematographer because Askins had become a true mentor. “I was constantly watching what Tony was doing,” says Baum. “He explained how he was lighting, and I learned over a period of several years.”

“To get another chance on working on the show that you moved up on, 15 years later, is very unique and gratifying.”

When Askins decided to retire in 2005, he suggested Baum take over, and show runners David Kohan and Max Mutchnick, and director James Burrows agreed. “I felt prepared, but it’s always a learning experience when you move up,” Baum remembers. “What I learned from Tony is how he handled his lighting, grip and camera crew. As a DoP, people look to you for certain things and you have to be able to navigate through a lot of different situations. I also learned from Tony to have a lot of patience; you’re always actively practicing it. I learned how to treat other crafts on the set with total respect. Tony was well known for never raising his voice. He was a different person than I am — I’m not always a person of few words the way he was — but I don’t raise my voice either.”

Baum would photograph two seasons of Will & Grace before the show wrapped in 2006. He then moved on to shoot such shows as The Class, Gary Unmarried, The Soul Man, Hot in Cleveland, Sullivan & Son, 2 Broke Girls, The Millers, Mike & Molly, Crowded, Superior Doughnuts and Man With A Plan — earning eight Emmy nominations and a win in 2015 for his work on Mike & Molly, along the way — before returning to Will & Grace for the show’s successful 2017 reboot.

“Receiving the Emmy for Will & Grace was of course very special to me, Jim Burrows, Max and David,” says Baum. “To get another chance on working on the show that you moved up on, 15 years later, is very unique and gratifying. Tony called me shortly afterwards, and we had a longer chat than usual. He told me how much he enjoyed the show and how proud he was. It was a very emotional conversation; I thanked him again for setting a fine example in character, and taking the time to guide and educate. Not realizing it would be the last time we would talk, Tony passed away a few weeks later.”

Yet a legacy of excellence continues.