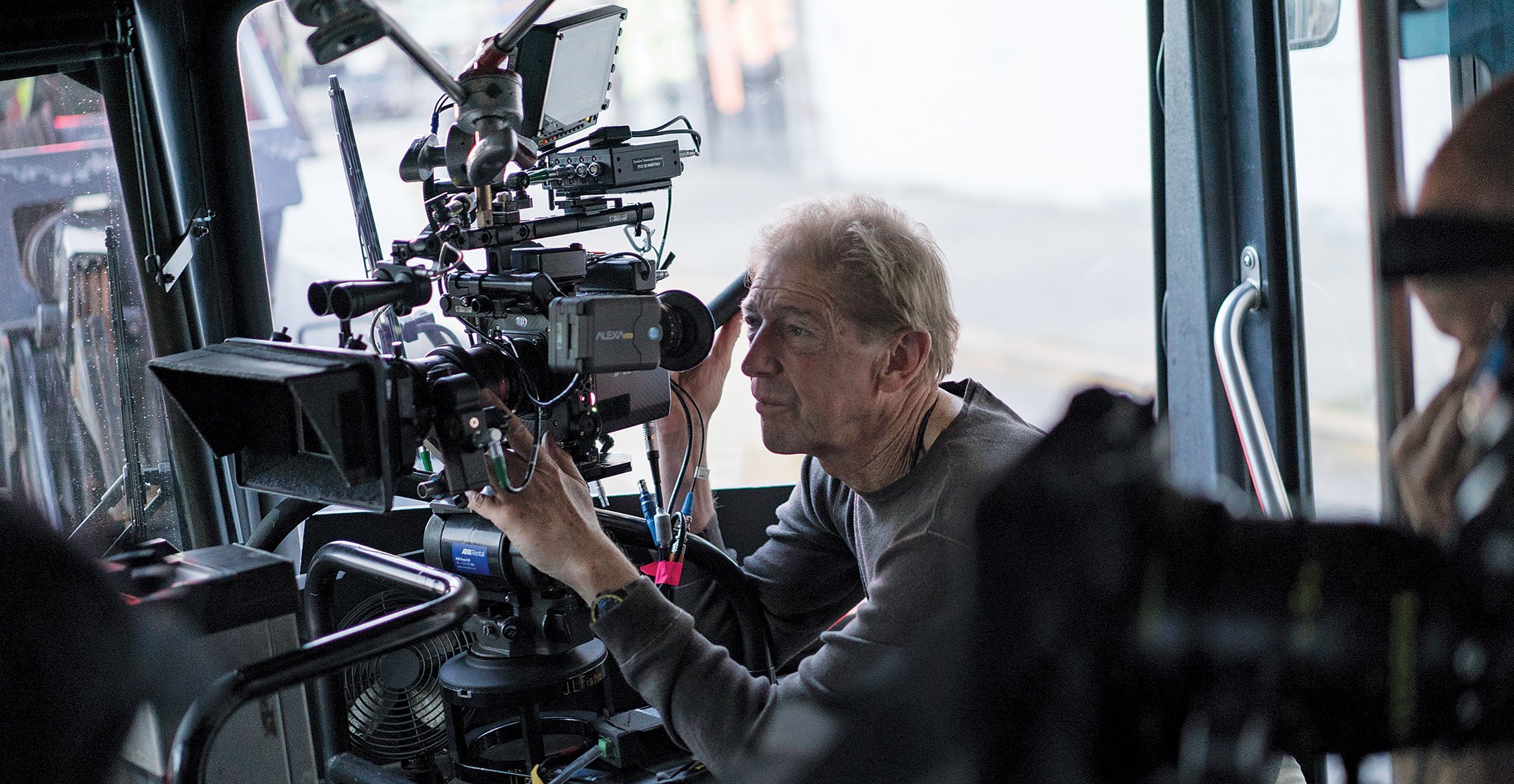

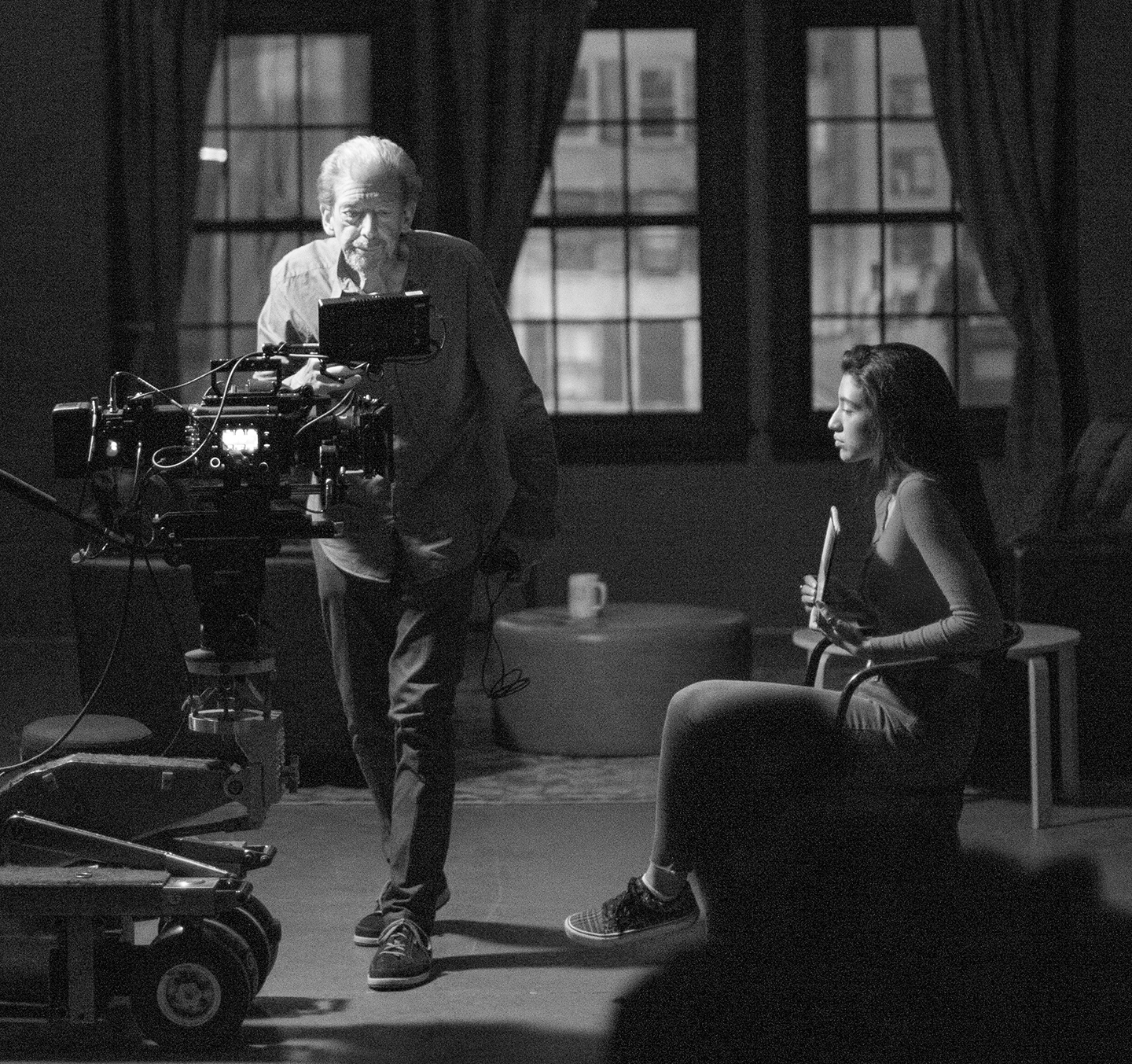

Artistry in Balance: Fred Elmes, ASC

With an instinct for collaboration, the ASC’s 2020 Lifetime Achievement Award honoree aims to serve the storytelling.

“I have to be moved by the story, and I want to build a relationship with the director that allows me to ask intimate questions about why the story moves them.” — Frederick Elmes, ASC

Whereas some take a circuitous route to a life behind the camera, the path of Frederick Elmes, ASC — this year’s ASC Lifetime Achievement Award honoree — was steady, straight and started at a young age, when his father gave him a 35mm Leica. Raised in Mountain Lakes, N.J., Elmes immersed himself in still photography, which led to shooting 8mm and 16mm home movies, and then to filming staged productions with friends and family.

“I grew up with movies,” he recollects, “especially Hollywood movies — musical comedies, Buster Keaton, and Abbott and Costello. My brother and I saw The Day the Earth Stood Still at a time when you could see two or three movies for a couple of bucks, and I remember sitting through it twice because I really dug it.”

Elmes attended the Rochester Institute of Technology as an undergraduate; he studied photo illustration, art history and photojournalism. His interests began to pivot toward filmmaking during that time, and after graduating from RIT, he enrolled in the newly established graduate-film program at New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts. There he was taught by Czech cinematographer Beda Batka, among others, and worked as Batka’s teaching assistant and as a projectionist in the school’s screening room, called “the Bijou.” Through that program, he met future collaborator Martha Coolidge and future ASC colleague Tom Houghton.

“Fred was in the class ahead of mine, along with Martha,” Houghton recalls. “My first week there, we had a Friday night screening of Husbands. [Director] John Cassavetes and [actor] Ben Gazzara were there in our small screening room; Martin Scorsese was standing in the back; and Fred was up in the booth.”

For Elmes, watching movies as a projectionist was as much an education as learning about them in a formal classroom setting. He credits the films of Ingmar Bergman, specifically The Seventh Seal (photographed by Gunnar Fischer), with opening his eyes to cinema that dealt with “bigger issues” than the typical Hollywood fare. He notes that it was Bergman’s work with Sven Nykvist, ASC on Persona that illuminated for him how story and visuals could be combined to create a total mood. “Bergman’s films convinced me the photography was a part of the storytelling,” Elmes explains. “He tells us something about the characters and drama through the camera and lighting. That stuck with me as a more interesting way to make films.”

Elmes graduated from NYU in 1972 and moved to Los Angeles after receiving a fellowship at the American Film Institute’s conservatory program. He continued to work as a projectionist there, and soon crossed paths with Cassavetes again. He was recruited as a camera assistant for A Woman Under the Influence through an arrangement with AFI that put students to work on the director’s low-budget features. Elmes later joined Cassavetes’ The Killing of a Chinese Bookie as camera operator, this time with much more responsibility.

“Working with John is where I learned to dive in and roll with the whole filmmaking process, to be present and watch how a scene unfolds,” Elmes says of the famously freeform director. “John liked the idea of a bunch of young people getting together to make a movie. He despised anything that ‘looked like’ a Hollywood movie. He also didn’t like to give people titles. On Killing of a Chinese Bookie, I got ‘camera operator,’ even though I did most of the lighting as well, and Don Robinson was our ‘gaffer’ — but it was really all of us together doing everything.”

While working on Chinese Bookie, Elmes began collaborating with fellow AFI student David Lynch on his surrealistic student film, titled Eraserhead, a process that would last about four years. “Eraserhead and Chinese Bookie were the first significant films for me because they were features,” the cinematographer says, “and because of the bond that forms during the time you spend in that constant give-and-take with the director.”

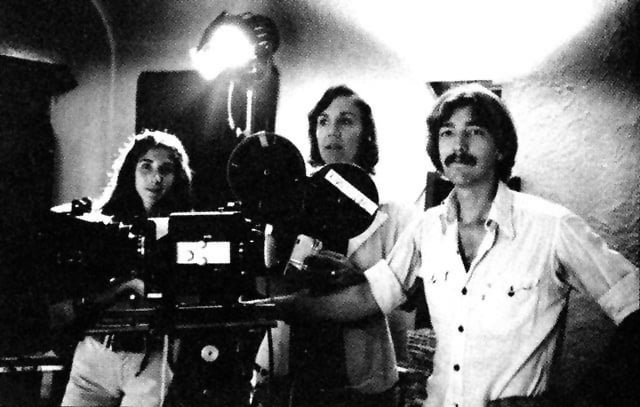

Elmes has since enjoyed many such collaborations — and continues to do so. For 1983’s Valley Girl, a Romeo-and-Juliet story about a sweet teenager from the San Fernando Valley (played by Deborah Foreman) and a punk from Hollywood (Nicolas Cage), Elmes was reunited with fellow NYU alum Coolidge. “The producers had bought the title Valley Girl after Zappa’s song became a hit, and they just wanted to make an exploitation film,” Elmes says. “The story and the charm of the film really came from Martha.”

He remembers the production as being incredibly challenging, with only a 20-day schedule and 60,000' of 35mm film at his disposal. “We’d work all through the night and then stay up to shoot the sunrise,” he says. But the myriad difficulties were beside the point. “What was exciting was taking a story from the writing to something you could share visually.”

“Valley Girl was a cheap film done with great artistry,” says Coolidge. “Fred wanted to go further with color than just controlling it. All the way through, we had a unique color design for each location, and characters even had their own colors. That movie is like bubblegum — very pop.”

River’s Edge (1986), directed by Tim Hunter, was inspired by a true story about a group of small-town teenagers coping with one friend’s murder of another. “We had an amazing cast, and Tim was working from a great script [by Neal Jimenez],” Elmes recalls. “It’s a gruesome story, but it happened. So, together we created the world where these events could unfold, and that process was quite satisfying.”

A similar underbelly lies beneath the small-town setting of Blue Velvet (1986), Elmes’ second feature with Lynch. “Creating a world with that dichotomy was wonderful,” Elmes relates. He describes Lynch’s creative process as meticulous, noting that the film’s opening scene — a slow-motion sequence featuring white picket fences, children crossing the street, and firefighters waving from a red fire truck passing by — was conceptualized and plotted out long before the cameras started rolling. “David’s process was holistic; the camera movement, the light and the mood on the set were all integrated with the way he directed the actors. It all became of the piece.”

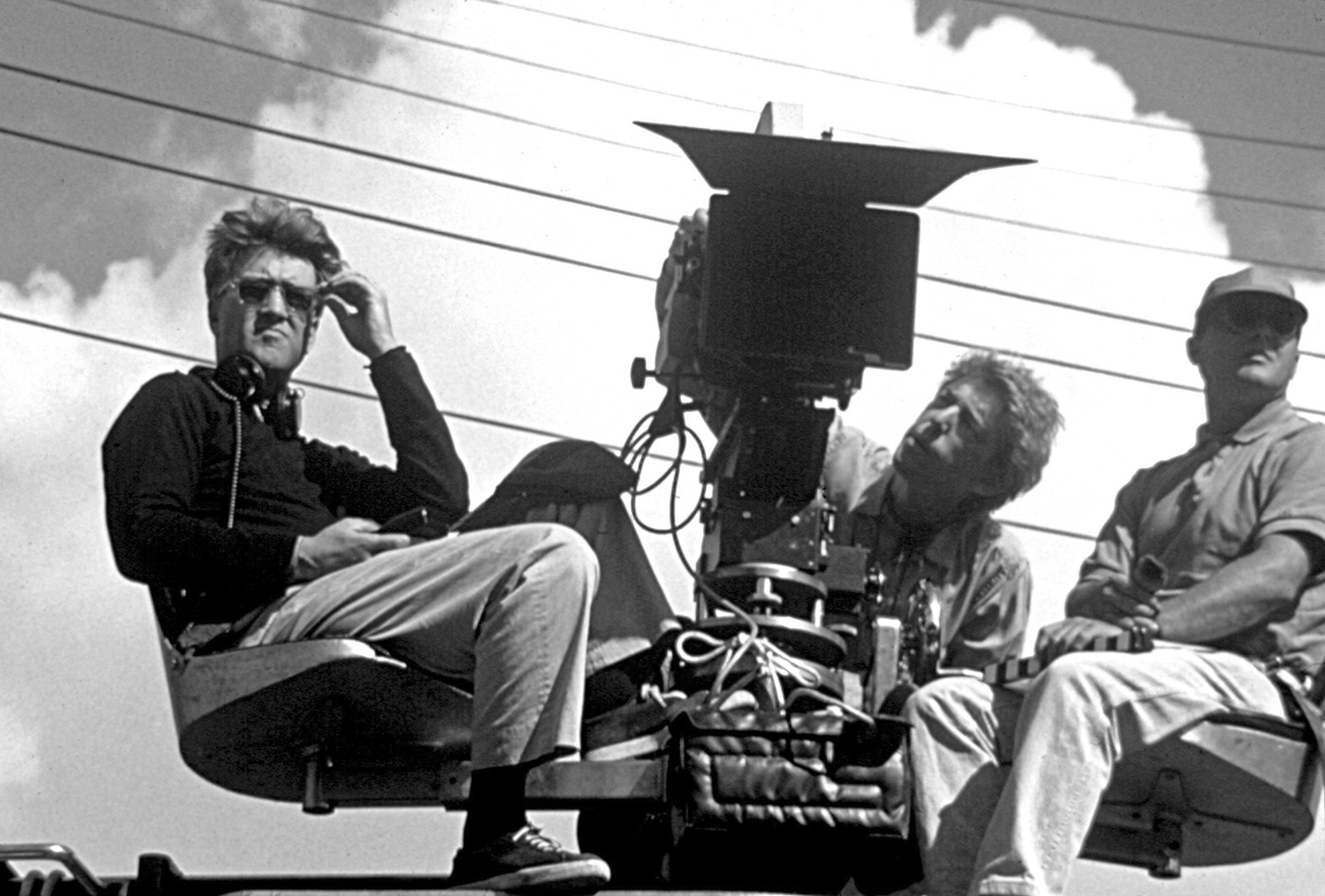

He and Lynch, who were honored with Camerimage’s Duo Award in 2000, continued their exploration of light and darkness with Wild at Heart (1990), an erotic thriller, road movie and berserk homage to The Wizard of Oz. Elmes’ photography sets the screen ablaze. “The fascination with fire, the flames, the lighting of a cigarette — all of that was in the script,” he says. “I did some early camera tests to see how dramatic a close-up we could make of a match striking and lighting a cigarette. We made a massive outdoor bonfire for the opening-title sequence against the wall of flame. It was a major undertaking, and it reflects the enthusiasm we had for making our vision a reality.”

Technical aspects aside, it’s the story at the core of the film — pure love vs. pure evil — that continues to fascinate Elmes. He points to the memorable scene in which Lula (Laura Dern) and Sailor (Nicolas Cage) are driving in rural Texas, broke, on the run, and unable to find anything but bad news on the radio. Suddenly, Sailor finds a speed-metal station. Their car screeches to a halt, and the camera cranes up to a wide, high angle of the couple dancing on the side of the road as the burning sun sets dramatically in the background:

“I still find the scene moving when I watch it now,” the cinematographer says. “The funny thing is that it was all filmed in just a few minutes. The sun was really setting, and there was no time to discuss the shots. We just went with our instincts.”

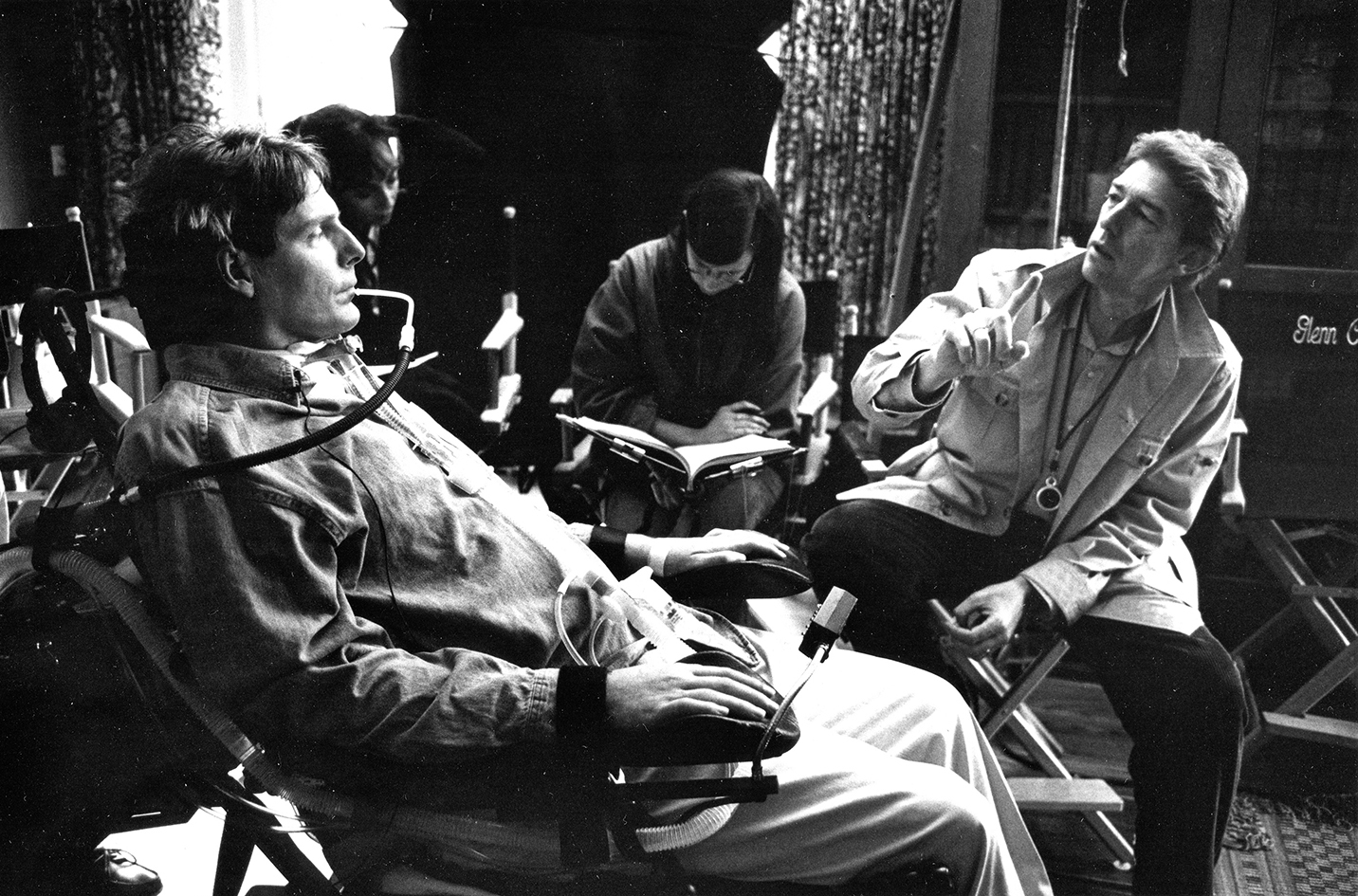

A world away, in New Canaan, Conn., Ang Lee’s The Ice Storm (1997) follows two dysfunctional families as they struggle to cope with thawing social norms in the early 1970s. Lee was just coming off the success of Sense and Sensibility, his first English-language film, and Elmes went into their first meeting impressed by how different the Taiwanese director’s films were from one another. “I had a great deal of confidence in Ang’s ability to tackle a story about that pivotal moment in this country, even though he had not experienced it firsthand,” Elmes says. “The human drama is what he fully understood.”

Elmes’ art-history education came into play on the project. He and Lee drew their visual inspiration from the Photorealist Movement of the late 1960s and early ’70s, specifically the work of Ralph Goings and Richard Estes. “It was a painting style that grew out of abstract expressionism and minimalist art. It tried to simplify the detail in things and use architecture and light differently. Ang and I really connected on that.”

Another filmmaker with whom Elmes has enjoyed multiple collaborations is Jim Jarmusch. Their latest feature together, The Dead Don’t Die, opened the 2019 Cannes Film Festival, and they have teamed on several others, beginning with 1991’s Night on Earth. Prior to that, Jarmusch had made a number of pictures with cinematographers Tom DiCillo and Robby Müller, NSC, BVK. “Robby wasn’t able to shoot Night on Earth, and I was a bit freaked out by that,” Jarmusch admits. “I wanted to meet Fred based on what I knew about his films and the people who worked with him, so we met in L.A. Afterwards, I heard that he told some people he felt I didn’t like him, which was funny because I got the feeling he didn’t like me!”

In fact, Elmes had been extremely impressed by Jarmusch’s Stranger Than Paradise and was keen to work with him. “Jim asked if I wanted to do a feature film made up of five short stories in several different languages, all taking place at night in taxicabs in five different cities during the winter,” Elmes recalls. “I said ‘yes’ because I thought it would be an adventure, and I liked his films. I’ve been fortunate to work with him ever since.”

Jarmusch characterizes Night on Earth’s production as extremely complicated and says Elmes’ indefatigable grit was instrumental throughout the shoot. “In Helsinki, Fred had a variable-speed motor built to control the panning of our lights while we were driving,” the director recalls. “Then we had the engine removed from one of the cars so we could put Fred and the camera in the engine cavity. It was about 20 below zero, at night, in the winter. Fred is just very tough and strong. Even if I want to call it, he’s ready to get another setup. You almost have to pull him off the set sometimes!” Jarmusch notes that Night on Earth co-star Gena Rowlands called Elmes “Young Freddie,” as they had worked together 20 years earlier on A Woman Under the Influence. The director also fondly recalls shopping for silk diffusions with Elmes in the lingerie boutiques of Paris.

“Fred’s aesthetic sense is highly sophisticated, but he also has a very technical mind, and those two things are in perfect balance,” Jarmusch notes. “One of my Native American friends calls it ‘going down the river with your feet in different canoes.’”

Elmes has worked long enough and widely enough that there are regular crewmembers he can call on just about anywhere in the United States or Canada. He cites New York gaffers Jonathan Lumley and John Raugalis and L.A. gaffer Mike Katz as particularly invaluable. “They always know the right way to approach me with a solution,” he notes. “The fewer words I have to use, the better.”

With recommendations from Haskell Wexler, Caleb Deschanel and Steven Poster, Elmes was invited into the ASC in 1993. He has since been elected to multiple terms on the Society’s Board of Governors, and is a current Board member.

Elmes’ cinematography has so far garnered a Primetime Emmy Award (for the “Ordinary Death” episode of The Night Of) and two Film Independent Spirit Awards (for Night on Earth and Wild at Heart). He was also honored in 2017 by the American Film Institute with their Franklin J. Schaffner Alumni Medal.

But as someone who sees his creative process as inextricably linked to that of his collaborators, recognition for his own work takes a little getting used to. “When I start a film,” Elmes says, “my hope is that I don’t repeat myself with an identifiable style, that my process helps the director see his or her film a little better, and that as a team, we can get there together.”

Introduced by director Lisa Cholodenko — with whom he collaborated on the HBO series Olive Kitteridge — you can watch Elmes accept the ASC Lifetime Achievement Award here: