Behind the Curtain: The Wizard of Oz

A cadre of creative minds infused MGM’s classic fantasy with a timeless supply of movie magic.

This article originally appeared in AC, Dec. 1998.

"For nearly 40 years this story has given faithful service to the Young in Heart; and Time has been powerless to put its kindly philosophy out of fashion. To those of you who have been faithful to it in return... and to the Young in Heart ...we dedicate this picture."

With those words, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer introduced what became the most popular Technicolor fantasy ever made, The Wizard of Oz. The picture was produced in 1938-’39, with the Great Depression slowly grinding to a close and the specter of global war looming on the horizon. With a final cost of $2,777,000, it was also one of the most expensive pictures ever made.

The script was based on L. Frank Baum's 1900 book The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, which sold over a million copies and launched a long series of Oz books. It had been dramatized on the stage and was filmed by the Selig Polyscope Company in 1910. In 1913, Baum founded the Oz Film Company in Hollywood and made three Land of Oz features, all of which failed. I. E. Chadwick produced a silent Wizard in 1925 which also flopped, despite featuring Larry Semon as the Scarecrow, Oliver Hardy as the Tin Woodsman, and Charlie Murray as the Wizard. In the 1930s, Samuel Goldwyn paid Baum $40,000 for film rights. Fantasy was still a hard sell in the Thirties, but it became easier in 1937 following the immense success of Walt Disney's first feature-length cartoon, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. Louis B. Mayer, the top man at MGM, bought the rights from Goldwyn for $75,000 in June of 1938.

MGM, then the world's richest motion picture company, stepped gingerly into the realm of "natural color." They began including two-color Technicolor sequences in silent features as early as 1924, with The Uninvited Guest. They also made several complete Technicolor features and shorts in the late 1920s and early '30s. Most producers were reluctant to go forward with color films even after the much-improved three-color process was introduced in 1934. Aside from the added expense, many patrons claimed that color films gave them headaches — the same complaint they had lodged against talkies a decade earlier. But by the end of 1938, with 25 Technicolor features in release, color had become a selling point instead of a liability. A look at, say, The Adventures of Robin Hood was sufficient to convert many naysayers.

In a last-minute decision, MGM finally took the three-color plunge for a 12-reel feature, Sweethearts, starring Jeanette MacDonald and Nelson Eddy. While that film was still in production, it was announced that The Wizard of Oz would also be filmed in Technicolor.

Mervyn LeRoy, a long-time Warner Bros. director, was lured away to MGM with a lucrative contract offer. He wanted to produce and direct Wizard, but was informed he was assigned to produce but not direct the high-budget project.

Shirley Temple, Twentieth Century Fox’s child superstar, was originally sought for the lead role of Dorothy, but for various reasons, the deal was never consummated. Universal’s singing star Deanna Durbin was also considered, but her childish contours were blossoming. Judy Garland, 16, was under contract to MGM and was a stronger singer than Temple, but was at first thought to be too old for the part. She was small, however, and careful costuming and a bust-flattening undergarment made her appear much younger. Her screen test convinced everyone that she was ideal for the part.

Casting of the Wizard was more complicated. LeRoy wanted Ed Wynn, who felt that the part was too small. The studio's next choice was W.C. Fields — a mind-boggling concept! Fields begged off because he was preparing You Can't Cheat an Honest Man at Universal. Others who were considered included Victor Moore, Hugh Herbert, Robert Benchley and Charles Winninger. It's easy to imagine any of these actors performing the role beautifully, but the final choice, Frank Morgan, proved to be the perfect Wizard.

Lanky, loose-jointed dancer Buddy Ebsen was signed to play the Scarecrow, a part for which he was ideally suited. However, another tall dancer, Ray Bolger, wanted the part so badly that he replaced Ebsen, who was then assigned to play the Tin Woodsman. Bert Lahr, the Broadway comic who hadn't quite caught on in movies, was hired as the Cowardly Lion — and almost stole the show from everybody.

LeRoy wanted Gale Sondergaard to play the Wicked Witch as a glamorous villainess, but the studio chiefs overruled him, demanding a traditional witch. Edna Mae Oliver and Margaret Hamilton were interviewed, and the role went to Hamilton.

Ziegfeld Follies star Fanny Brice was first considered for the Good Witch, but the final choice was Billie Burke, Ziegfeld's widow. May Robson and Sarah Padden were tested for Aunt Em; Clara Blandick got the part.

Noel Langley, Florence Ryerson and Edgar Allan Woolf were the credited authors of the final screenplay, which was begun in late February 1938 and completed in August. Other writers involved were Herman J. Mankiewicz, Irving Brecher, Robert Pirosh, George Seaton, Herbert Fields, Jack Mintz and Ogden Nash.

The tale begins in Kansas, where Dorothy lives with her Aunt Em and Uncle Henry and enjoys the friendship of three farmhands: Hunk, Zeke and Hickory. One day, Dorothy's dog, Toto, bites the vicious Miss Gulch, who obtains an order for the pet's destruction. Dorothy flees with Toto but runs for home after talking to Professor Marvel, a fortune-teller and balloonist. As she arrives, a tornado hits the house. Knocked unconscious, Dorothy awakes to find the house spinning through the air. When it crashes down, she emerges in Munchkinland, which is inhabited by little people, in the Land of Oz. The house has squashed the Wicked Witch of the East.

Glinda, the Good Witch of the North, arrives and slides the evil witch's magic ruby slippers on Dorothy's feet. Before Dorothy can break in her new heels, however, the Wicked Witch of the West swears vengeance. Glinda tells Dorothy to follow the yellow brick road to the Emerald City, where a powerful Wizard can help her get back to Kansas.

On the way she meets a Scarecrow who says he has no brain, a Tin Woodsman who claims to have no heart, and a lion who is a coward. The three join up and travel to the Emerald City, where a terrifying apparition appears and finally agrees to help them all if they will bring him the Wicked Witch's magic broomstick. It's a hazardous journey. As the group passes through the Haunted Forest, Dorothy and Toto are seized by flying monkeys who carry them away to the Witch's castle. Toto escapes and brings Dorothy's friends to rescue her, but they are also captured. When the Witch sets the Scarecrow on fire, Dorothy throws water on him. Some of it splashes on the Witch, destroying her.

Dorothy and her friends take the broomstick and return to face the Mighty Oz. In his palace, Toto pulls aside a curtain, revealing a man operating levers that create the illusion of the Wizard. Humbled, he gives the Scarecrow a diploma, the Tin Woodsman a testimonial and the lion a medal, convincing them that they now have the virtuous qualities they previously lacked. Admitting that he is just a balloonist from Kansas, the Wizard offers to take Dorothy home. However, Toto jumps out of the gondola to chase a cat and Dorothy chases after him as the balloon is carried away. Glinda tells her she can go home if she clicks the heels of the ruby slippers and thinks "There's no place like home" three times. After reciting this magical mantra, Dorothy awakens in her bed, surrounded by her aunt and uncle, the three farmhands — who bear an uncanny resemblance to the Scarecrow, the Tin Man and the Lion — and Professor Marvel, whom we realize is the Wizard.

Principal photography of this fantastic adventure story began on October 13 with Richard Thorpe directing. Hal Rosson, ASC was director of photography, with Allen B. Davey, ASC serving as Technicolor cinematographer. Thorpe had made four great Tarzan films and the remarkable Night Must Fall, but the rushes soon convinced producer LeRoy that the director was not capturing the desired fairytale quality. After 11 days, production was halted and George Cukor assumed directorial duties. But Cukor left after a week to begin preparing Gone With the Wind. He was replaced by Victor Fleming, a hard-boiled former cinematographer. Ironically, Fleming later replaced Cukor on GWTW as well.

In late October, Ebsen became seriously ill from breathing the powdered aluminum dusted over his Tin Man makeup. He recovered after six weeks in the hospital, but MGM had already borrowed Jack Haley from Fox to replace him.

The next casualty was Margaret Hamilton, who was supposed to disappear from Munchkinland in a burst of smoke and fire. To do this, she had to step on a certain part of the road and descend on an elevator. After several takes, the pyrotechnics ignited too soon and she was seriously burned on the face and hand. Later, Hamilton's stunt double, Betty Danko, was badly injured while riding (on wires) the witch's smoke-spitting broomstick. The prop exploded, sending her to the hospital for 11 days and leaving her with permanent scars.

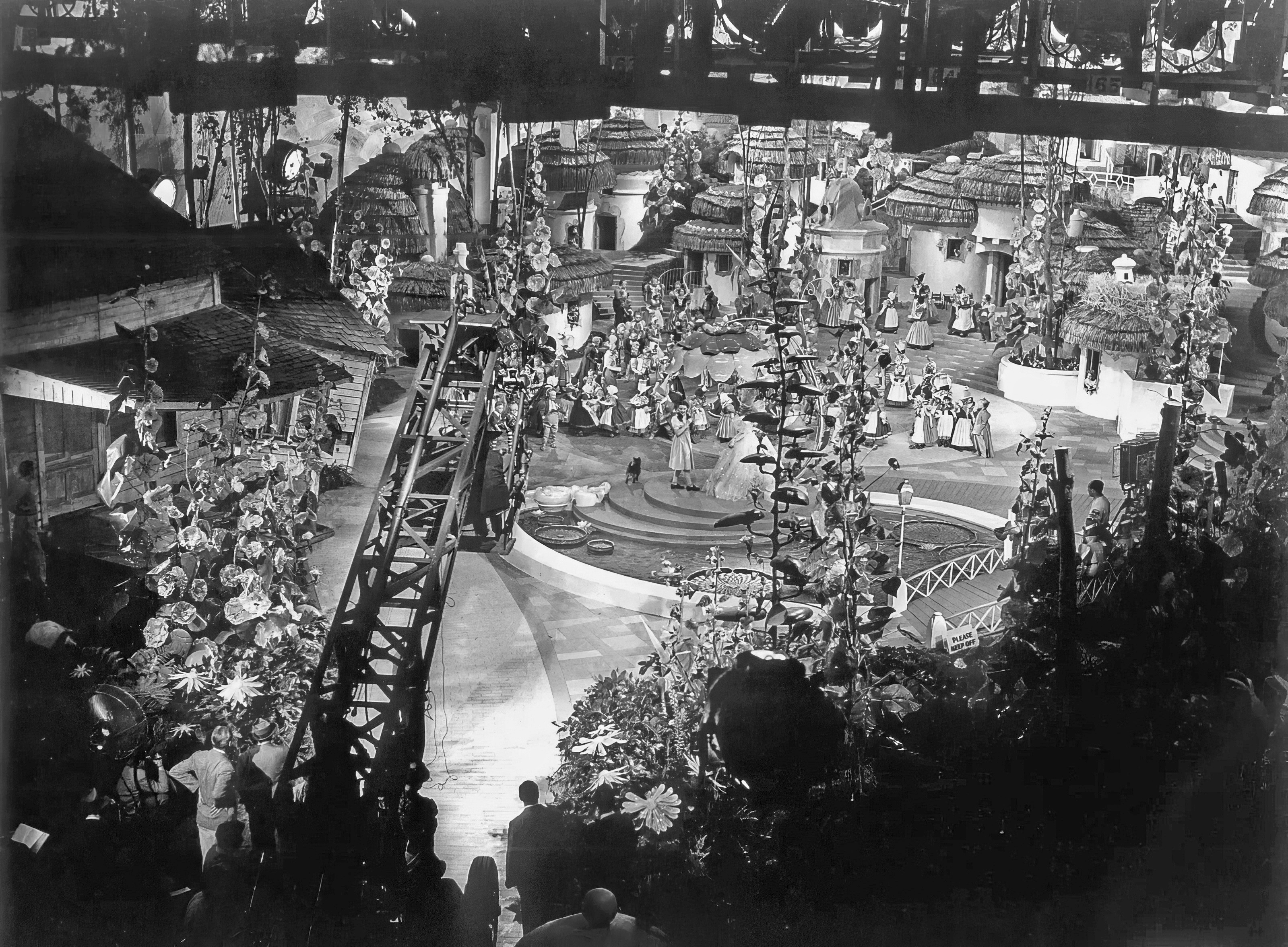

The Technicolor photography for Oz was difficult because of the vastness of the sets. It would have been next to impossible except that Technicolor had just introduced its new, "faster" film, which today would have an ASA rating of about 50. Even so, Rosson was astonished at the number of big arcs required to light the picture. The heat was enormous and was especially torturous for the actors in their heavy costumes. On some sets, as many as eight cameras — about a third of Technicolor's inventory — were used, with one getting the overall scene while others were hidden among the scenery for tighter shots. The main camera, mounted on a huge crane, was kept moving, tracking with the subjects in most shots.

A preponderance of shiny surfaces, such as the Tin Man's metallic suit, the big prop emeralds, and even the sequined red slippers, caused problems by creating distracting reflections.

The Kansas scenes at the beginning, directed by King Vidor, were photographed in black-and-white. They were printed in the MGM laboratory's beautiful but long-extinct Sepia Platinum process, which not only gave the images a sepia tone, but lent an iridescent quality to the highlights. The process was also used in other pictures of the era, such as Ziegfeld Girl, Tarzan Finds a Son! and Girl of the Golden West. In Oz, frames were hand-painted in order to create the transition to color.

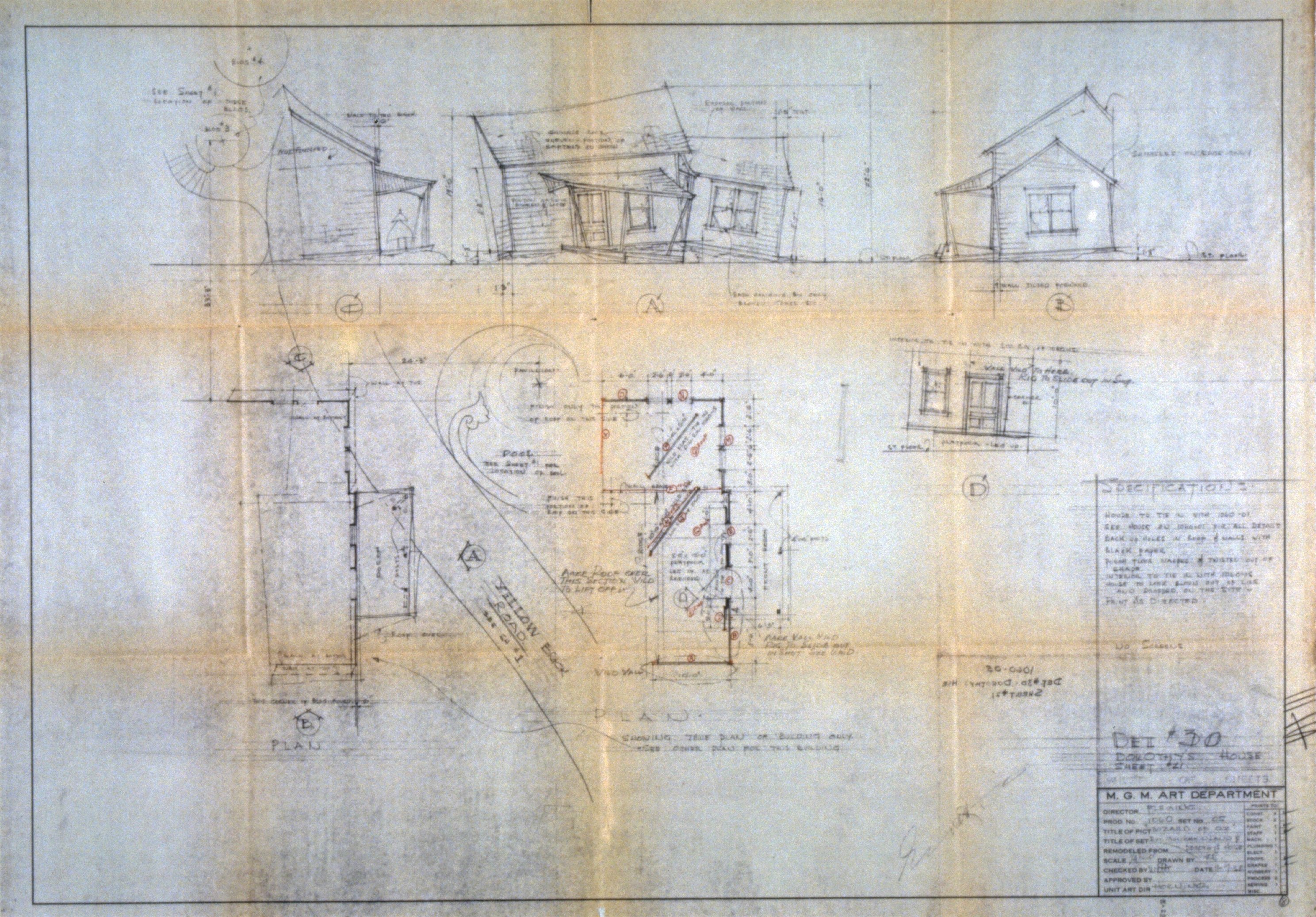

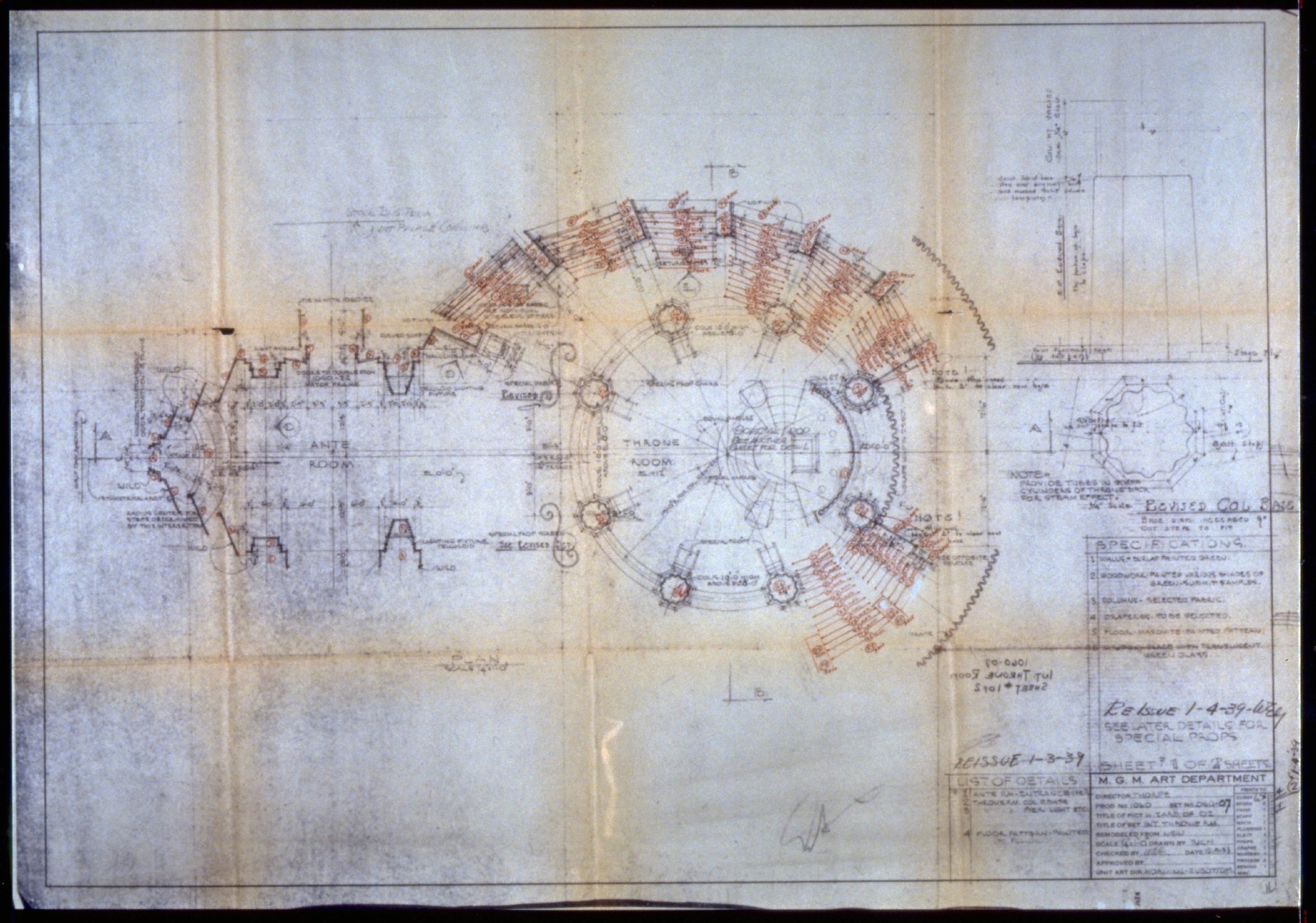

Wizard also presented many problems not previously encountered in three-strip photography because of its numerous special effects scenes. Two effects units operated within Cedric Gibbons' art department. A. Arnold Gillespie was in charge of miniatures, projection process, and mechanical effects. Warren Newcombe headed the matte painting section, where he and his assistants produced what the studio called "Newcombe Shots."

A commercial artist from Massachusetts, Newcombe entered the movie field in 1922 by producing an art film entitled The Enchanted City. That led to his employment by D. W. Griffith for America (1923) and, in 1925, the start of his long career at MGM. Some of the best remembered 'beauty shots' in Oz are Newcombe composites, such as scenes in which the towering buildings of the Emerald City loom in the distance as Dorothy and her friends follow the yellow brick road. These structures strongly resemble Alex Raymond's 1934 drawings of Ming's Diamond City in the newspaper cartoon Flash Gordon. In such scenes, the live action was photographed on a section of the road and the masked scene was doubled into a matching blacked-out area of the painting. A few scenes, such as the establishing shot of the witch's castle, are complete paintings, 40 inches wide and without live action.

Gillespie, a husky Texan from El Paso, began his career as a set designer at Paramount in 1922, then joined MGM as an art director when the studio opened in 1925 and stayed for 41 years. In 1936, he replaced James Basevi as special effects chief in charge of miniatures, projection process and mechanical effects. Although he won Oscars in 1944 (Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo) and 1947 (Green Dolphin Street), his most celebrated achievement is the tornado in Wizard.

An oft-told legend maintains that the tornado was created by manipulating a windblown silk stocking through a tabletop set. It was hardly that simple.

Gillespie, a long-time pilot, decided that a tornado funnel was shaped something like the wind socks seen at airports. A miniature of the Kansas farm, scaled at 3/4" to 1', was built on Stage 14. It included cornfields, the house, the barn, and fences. Gillespie had a 35' wind sock cast in thin rubber and ordered a steel gantry specially built and suspended from the ceiling. It was rigged to move the full length of the 200' stage. The top of the sock was attached to a small car on the bottom of the gantry. By manipulating the car, the effects experts could make the tornado twist and perform erratic moves. The bottom of the funnel was anchored in a hidden slot that ran the length of the stage.

The first test was a failure because the rubber funnel refused to twist like a tornado. A subsequent version made of muslin whipped around satisfactorily, but it quickly tore loose at the bottom. Another was built, and this time it was reinforced throughout with piano wire. This one twisted and careened wildly. Fuller's earth was fed into the muslin funnel from above, and enough of it escaped through the porous muslin to blur the edges of the sock realistically. The big cloud of dust that surrounds the bottom of a twister was made by blowing Fuller's earth and compressed air in from underneath. Stormy skies were created with dense smoke fed from the catwalks, while patches of spray-painted cotton attached to 8' x 4' foreground glass plates were placed in front of the camera to mask the top of the tornado and the gantry. Tornado shots were used alone and as process plates to be projected behind Dorothy during her attempt to elude the funnel. The farmhouse, which was about 3' high, was swept aloft on piano wires.

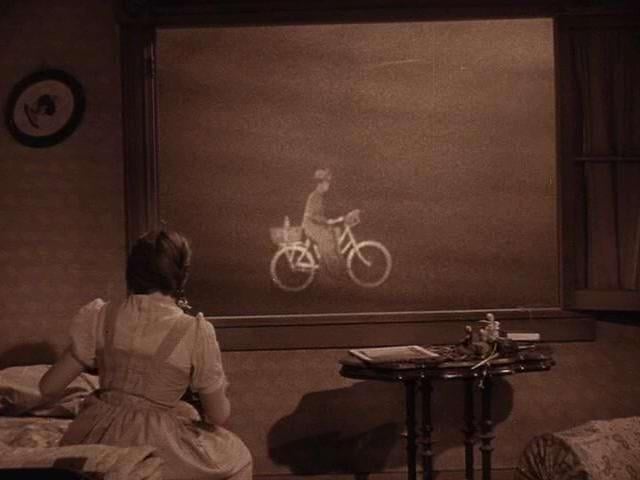

A strange sequence follows in which Dorothy and her house are inside the twister and she sees various things picked up by the cone go hurtling by. The walls of the spout consisted of a circle of painted muslin, 35' in diameter. The camera was placed in the center and spun rapidly while the muslin remained stationary. Then the individual objects that swirl past — men rowing a boat, Hamilton riding her bicycle, Auntie Em in her rocking chair, etc. — were photographed separately and double-printed onto the spinning background. The resulting composite was back-projected outside Dorothy and the window.

The expensive gantry and its perambulating car saw further service in getting the witch's flying monkeys airborne. A dozen monkeys seen in the foreground and in scenes where they harass the heroes were men in costume, all selected because of their slight physiques. They were flown on piano wires and their wings were made to flap by means of small hidden motors. The wires had to be kept taut because kinks caused them to break. Safety nets and pads usually saved the day, although several "monkeys" landed in the hospital.

Model monkeys in various scales, of sizes down to six inches, flying on wires hanging from the tornado gantry, were used in the backgrounds and miniature landscapes. Marcel Delgado, the sculptor and technician who had made the models for The Lost World and King Kong, cast the bodies in rubber over aluminum armatures, with hinges for the wings. Each model required two wires for the bodies and two for flapping the wings. The mass of wires — more than 1,000 altogether — necessitated numerous retakes due to breaks.

Gillespie was also called in to photograph scenes in the poison poppy field, for which it was necessary to have the camera move along the ground surrounded by flowers. He had tracks made of half-tubing and designed a special dolly equipped with half-tube runners that fitted over the tracks. The huge camera moved smoothly and quietly over the well-lubricated tracks.

In one memorable scene, Hamilton's face appears in a large crystal ball. The previously photo-graphed, which was projected from the side onto a mirror set at a 45-degree angle, relaying the image onto a small translucent screen inside the hollow ball.

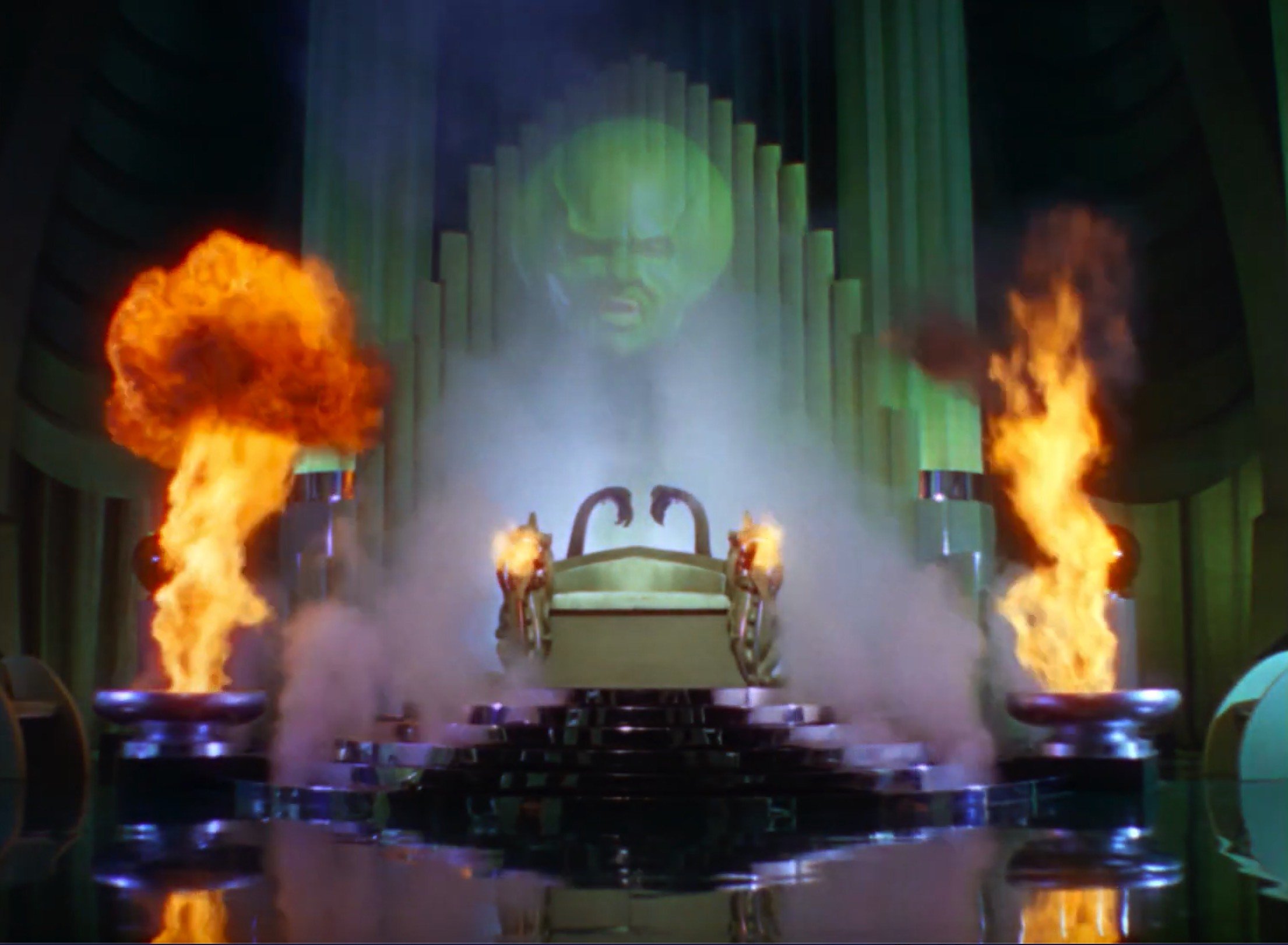

The giant floating head of the Wizard was front-projected onto heavy clouds of white steam piped in from outside the stage. The front-projection process used today had not been developed at that time, but the close-up registered effectively on the steam in one of the larger projected images that had been attempted in color.

The arrival of Glinda the Good Witch in Munchkinland is a deft bit of fantasy. A silver ball floats like a giant bubble into the scene, looming larger and larger as it moves into the foreground of the set. Upon alighting, it dissolves to reveal Glinda. The actual ball was about 8" in diameter and was not moved while being photographed. Instead, the camera moved to make the ball appear to describe the path it was to follow. The set and actors were photographed separately, and the two films were then printed together as a simple double exposure without protection mattes, which lent the ball an ethereal quality.

Principal photography wrapped on March 16, 1939, after five months of production. The final cost was $2,777,000.

The Wizard of Oz was highly successful in its New York run at the Capitol — most of the New York critics hated it, but who cared? — and the Hollywood premiere at Grauman's Chinese Theater was lavish. The Harold Arlen/E. Y. Harburg songs, especially "Over the Rainbow," were well-received. The picture's timeless appeal has since made it a cherished tradition in theaters and on television the world over.

Our thanks to Fred Detmers, Buddy Ebsen, Lois January, and the late George Cukor, Billy Curtis, Marcel Delgado, Harold Rosson, ASC and Harry Wolf, ASC.

The Restoration of Oz

Chances are that no film has been seen by more people than The Wizard of Oz. Director Victor Fleming's 1939 classic has made an indelible imprint on American pop culture, giving us durable metaphors ("the yellow brick road") and memorable lines ("We're not in Kansas anymore").

It's safe to assume that most moviegoers have experienced The Wizard of Oz through the narrow perspective of a television screen. An ambitious restoration project by Warner Bros. has returned the film to its original splendor, with the possible addition of a special effects dance sequence involving the Scarecrow. (At press time, that decision had yet to be made.)

Pacific Title/Mirage was selected by Warner Bros. to restore the black-and-white segments of The Wizard of Oz, plus the additional Scarecrow sequence, which was filmed in Technicolor. Given the possible inclusion of the extra sequence, Pacific Title/Mirage was responsible for scanning some 44,500 frames (of the approximately 85,000 in the original 101-minute movie) for image processing, and then recording them back onto film.

That figure surprises those who only remember the black-and-white footage from the scene in which Dorothy opens the door of her Auntie Em's house to discover that a tornado has transported her to a Technicolor universe. Phil Feiner, president of the optical division of Pacific Title/Mirage, reminds us that the first two reels of Oz, as well as the last, are black-and-white.

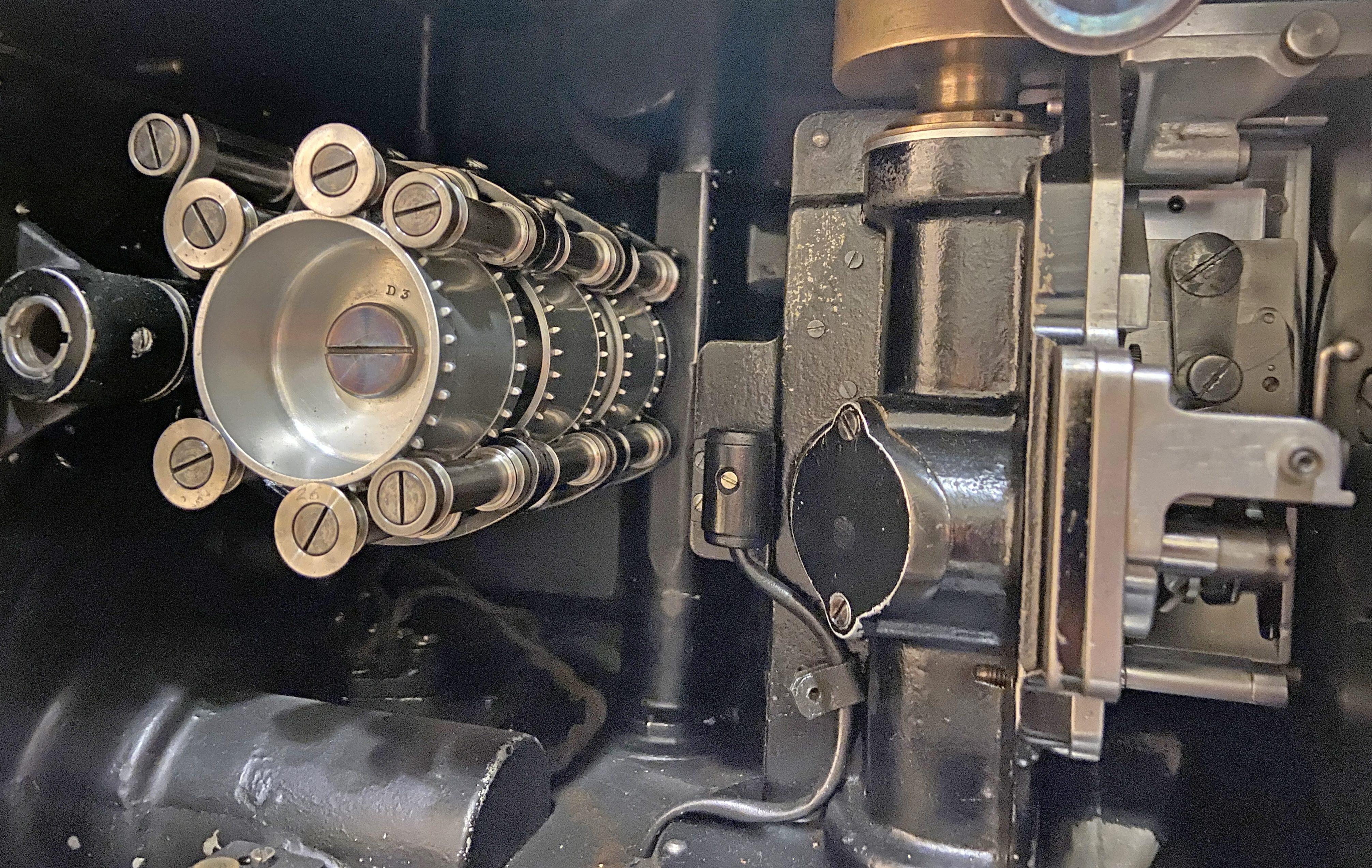

Dye fading is not inherent to the Technicolor three-strip process. The images themselves were recorded simultaneously onto three strips of a special black-and-white film custom-made by Kodak: one strip was sensitized to record the density of cyan colors, another was sensitized to yellow and a third to magenta. A patented imbibition process was used to transfer the image information onto release prints for theaters. The vivid colors came from dyes added during this process.

Feiner notes that the original Technicolor imagery can be re-created by making separate passes with each of the three strips directly onto an answer print. That's presuming that the original black-and-white separations have not been scratched or damaged in other ways and that the base on which it is coated has not shrunk. (Cinetech handled this portion of the restoration project.)

The original black-and-white negative photographed by Hal Rosson was lost in a 1970s fire at The George Eastman House in Rochester, New York. The only remaining copies were protection fine-grain intermediates made by MGM Labs in 1960. In 1984, a copy was struck from one of those intermediates. However, in 1960, the fine-grain film stocks and the techniques employed for making optical and contact copies were nowhere near as sophisticated as they are today. "We now use wet-gate technology to protect the film when it is contact-printed or duplicated with an optical printer," Feiner explains. "That eliminates the major source of cell abrasions and emulsion digs, which can occur during the duping or printing process. I would guess that the original negative was probably used to make more than 10 and perhaps as many as 200 release prints. The result was that there were scratches, embedded dirt and other anomalies copied onto the fine-grain master in 1960."

The restoration team at Pacific Title/Mirage tackled the task of restoring Oz with missionary zeal, which Feiner attributes to the company's deep roots in the industry. Pacific Title was founded in Los Angeles in 1919, the very same year that the ASC came into being. Feiner joined the company in 1977 as an optical camera operator on the night shift. "We're proud of our history," Feiner says, "which includes a large amount of the optical restoration work on the Star Wars trilogy. I believe we bring a unique film aesthetic to the use of digital tools for restoration."

Feiner notes that advances in digital film conversion and image-processing technologies provides a powerful toolkit for restoration projects. This proved to be a key advantage on the Oz undertaking, given the job's aggressive eight-month schedule.

The picture's fine-grain master was stored at the Library of Congress. Pacific Title/Mirage converted it to digital format with a Kodak digital film scanner at full film resolution. According to Feiner, this process requires 4K x 3K of digital data with 10 bits of log space per pixel. "Some people say 3K, or even 2K, and 8-bit log space per pixel is sufficient, but this film is an important part of our heritage and culture," he says. "Countless millions have seen it on TV. Finally, they can now see it in a cinema the way it is meant to be seen. It would be a crime to cut corners and do anything in a sub-standard manner."

The fine-grain intermediate provided by The Library of Congress showed no visible signs of vinegar syndrome or shrinkage, and it had a stable base. Feiner opted to make a contact liquid-gate dupe negative of the fine-grain IP, which eliminated the worst of the abrasions and emulsion digs. "We test scanned the original fine-grain and the dupe to see if there were discernible differences in resolution, sharpness and overall image quality," he says. "When we scanned our dupe at full film resolution, there was no loss in image quality. If we had scanned from the original fine-grain, we would have copied the abrasion and emulsion digs and that would have required extensive digital paintwork.

If one scans a full-aperture anamorphic frame in full color, the file size would run about 45 megabytes. However, scanning from a black-and-white element at full film resolution yields about 13 megabytes per frame — a rate that allows for more efficient data management at faster speeds.

The digital restoration work was executed on Silicon Graphics 02 platforms and several dual-processor Octanes running Matador Paint and Cineon applications software. The workstations were networked to an SGI Origin 2000 file server that provided high-density image storage and rapid transfer rates. "We elected to use Cineon software for automated dust-busting, with one important provision," says Feiner. "You have to be very careful that you don't lose fine details like highlights in people's eyes. The only way to do that is to compare the processed images on the computer screen to a matching frame of the source material."

The images were stored on the high-speed disk array for display at 2K resolution. The digital artists were then able to flip the display between the source material and the processed images. "We assembled and trained a staff with the appropriate skills and film sensibilities, plus the dedication needed to do the job properly," Feiner says. "The supervisor, Mark Freund, has been a great optical camera operator for us for years."

The dancing Scarecrow sequence was an outtake stored on 250 feet of film — less than three minutes of screen time — in the CRI (Color Reversal Intermediate) format. All of the original three-strip Technicolor film from that period was recorded on a potentially flammable nitrate-based emulsion. Feiner speculates that MGM decided to rid its lot of nitrate-based film sometime in the late Sixties or early Seventies.

When Feiner inspected the Scarecrow scene, the image seemed slightly off. "I noticed that there were two frames, right before the pictures started, with clear lines outside the perforations," he says. "Most people wouldn't have noticed that, but I've worked on a lot of trailers for TV in CRI format. Still, it took me about a day to discover what had happened. One of our people [Vince Roth] had worked in the MGM Labs optical department for 27 years, and he remembered an optical camera operator who had worked on those conversions."

MGM Labs had set up a production line to copy the nitrate film onto CRIs, recording from the emulsion side rather than the base side. That was then considered to be the archival master. When requests were made for duplicate negatives, MGM Labs fashioned a copy from this source. "I realized I had one of the dupes," Feiner says. "Warner Bros. did a diligent search and found the original CRI. That was important, because we wanted to be as close as possible to the original image quality. There's no magic bullet with digital technology — you can only scan in the image quality on the source material."

After scanning, the image quality was cleaned up by the digital artists, who removed dust and dirt spots and painted out the wires used to help actor Ray Bolger to fly in the Scarecrow dance number. The artisans also compensated for yellow dye fading. "It took an aesthetic eye," he explains. "Dorothy is in the scene in question, and we needed to match her skin tones to scenes on either side of the cutting done by the editor."

The digital files for both the Technicolor and black-and-white sequences were converted to intermediate film with a Kodak laser film recorder. "Our goal was simple," Feiner says. "We wanted to provide a pristine internegative which accurately emulates the original Wizard of Oz, and provide an enduring film record for future generations to enjoy."

By Bob Fisher

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.