Mank: A Writer in Exile

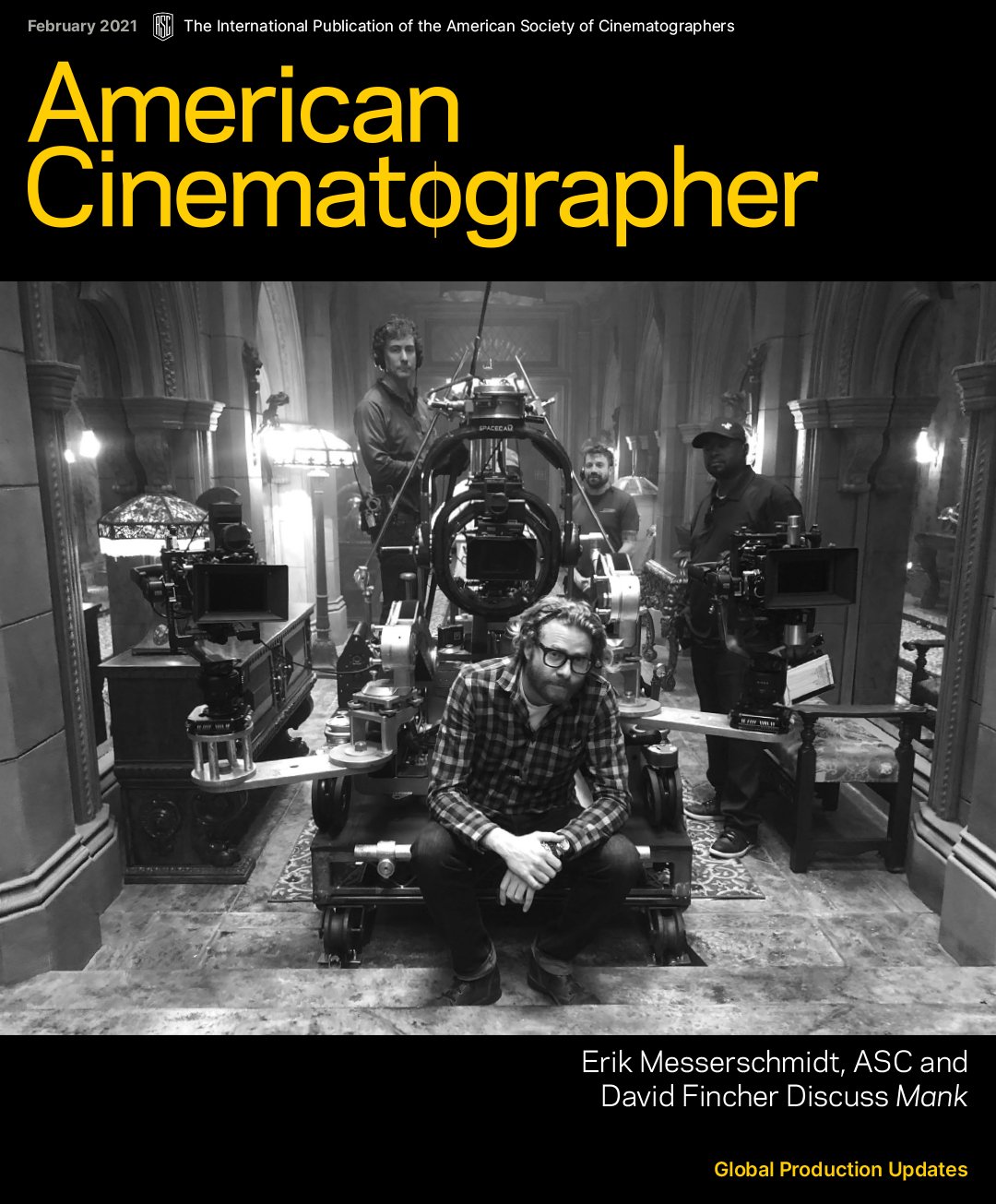

Cinematographer Erik Messerschmidt, ASC and director David Fincher discuss their creative collaboration.

Photos courtesy of Netflix

Mank frames the origin story of Citizen Kane from the perspective of screenwriter Herman J. Mankiewicz as he’s hit a low point in life. Alcoholic, world-weary and hobbled by a broken leg sustained in a car crash, Mankiewicz is trundled off to a dusty desert cottage in Victorville, Calif., accompanied by a nurse and a typist tasked with keeping their cantankerous patient off the bottle so he can complete a screenplay for Orson Welles — a script that will serve as the foundation of Kane.

Pressed by Welles to finish the project, the bedridden “Mank” (as he’s known to his friends and colleagues) struggles to find creative inspiration, eventually drawing upon his memories of businessman, newspaper tycoon and politician William Randolph Hearst. Flashbacks transport us back to Mank’s headier days as a handsomely paid Hollywood scripter. After amusing Hearst with his barbed wit on a movie location, Mankiewicz is invited to mingle with members of the mogul’s inner circle and renews a friendship with Hearst’s mistress, actress and comedian Marion Davies. Mank’s Hollywood career is thriving, and his social standing is on the rise, but his proximity to power allows him to observe its corrosive influence firsthand — souring his worldview, but ultimately informing the plot of Citizen Kane and the sardonically unflattering portrait of its Hearst-like protagonist, Charles Foster Kane.

The script for Mank was initially fashioned by director David Fincher’s father, Jack, a journalist and screenwriter, who empathized with Mankiewicz’s plight and leaned into the controversial assertions of film critic Pauline Kael, whose 1971 essay in The New Yorker, “Raising Kane,” maintained that Mankiewicz was almost entirely responsible for the Citizen Kane screenplay, with little input from Welles. (That thesis has since been partially debunked by Welles supporters, including director and former film critic Peter Bogdanovich.)

Following his father’s death in 2003, Fincher retooled the Mank script with the help of screenwriter Eric Roth, making it less antagonistic toward Welles. “I never felt that the film should be a posthumous arbitration — that’s never been of interest to me,” Fincher told AC during a 90-minute Zoom interview that included Mank cinematographer Erik Messerschmidt, ASC. “What was interesting to me was that it’s [essentially] Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead — here’s a guy in the wings, and it’s his experience of this situation. What I found fascinating about Mankiewicz was [that] 30 percent of his output as a professional screenwriter in Hollywood was uncredited. And for one brief, shining moment — on a movie he did when he was old enough to sign a contract and understand the terms expressly — he said, ‘No, no, no — I don’t want this one to get away.’”

“What’s great about Erik is that he’s a leader and a concise communicator. But he’s also a flexible thinker — he’s not somebody who’s proprietary.”

— David Fincher

The following Q&A is excerpted from the magazine’s conversation with Fincher and Messerschmidt about the Netflix project.

American Cinematographer: How would you describe your working dynamic together, and the evolution of your creative relationship?

David Fincher: What’s great about Erik is that he’s a leader and a concise communicator. But he’s also a flexible thinker — he’s not somebody who’s proprietary. He assesses what’s in front of him, and then he goes to work.

Erik Messerschmidt: I had seen Jeff [Cronenweth, ASC], work with David, and I had witnessed that relationship work well. Prior to becoming a cinematographer, I was working as a gaffer, and part of that job description, I think, is learning to assimilate and anticipate what people respond to and how they see the world, and then doing your best to fill in the gaps and figure out how you can be a supportive partner. I think that skill has really helped me as a cinematographer. David has a very specific way of seeing the world, and I think I see it in a very similar way, so it doesn’t take very long for me to understand what he is articulating.

Fincher: It’s good to be concise, and we try to communicate in the least amount of words, or in the least amount of time and the fewest number of interactions.

There’s a perception, David, that you’re a perfectionist on set. How would you address that notion?

Fincher: It’s not about chasing perfection; we’re trying to do the best with what we have in front of us. In my way of thinking, let’s take away everything that doesn’t work — from glitches and flares to bumps in the track or an unnecessary head turn. Let’s cleave all of that stuff away so that we’re just showing what we need people to see, and then move on. Let’s get rid of the distractions.

Do you still leave room for what ASC member Conrad L. Hall referred to as “happy accidents” — embracing the unpredictable occurrence in a creative way?

Fincher: Connie was a very wise man. Richard Edlund [ASC] says that, too, and I think it’s really true. Quite honestly, that’s what we’re trying to do while we’re shooting so many takes. We’re not just doing it to antagonize the Screen Actors Guild, you know? You’re doing it to say, ‘Okay, that’s a perfectly serviceable version of the scene, but now let’s do it a little faster,’ or ‘How fast can the actor say all of the lines, and still feel as if they’re saying it for the first time?’ If you give someone 14 or 19 shots at it, I guarantee you’ll have three or four mistakes that will be really interesting. So I guess [my approach] is a further extension of what Connie was talking about, or what Welles was talking about when he said, ‘A director presides over a series of mistakes.’ I’m forcing that — I am not trying to make it perfect. I’m trying to find those little moments where something interesting happens.

It happens frequently that actors stop themselves in the middle of a take. On Fight Club, Edward Norton had reams of on-camera dialogue and also a lot of voiceover. We would pre-record his V.O. so we could play it back. And I realized that almost every time he got on a tear and sort of lost his footing, he’d cut it short and say, ‘Oh, I’m so sorry, let’s stop for a sec.’ But I would take him over to the video monitor and tell him, ‘Look what’s happening on your face as you fall forward — you’re in freefall at this moment, and you’re panicking, but look at what’s happening.’ And he was like, ‘Wow, that’s interesting.’ And I would say, ‘Yes. Do not edit yourself. We’re trying to capture that moment when you’re falling forward and catching yourself. That’s what we’re here to do.’

On Mank, Amanda Seyfried proved to be a person who can’t wait to try something completely mad and inspired the next time around. And that’s when it’s fun.

“That scene with Gary involved a lot — he has to be drunk, yet cogent, and really specific about the points he’s making, but there has to be a degree of subtlety as well as the broad brushstrokes.”

— David Fincher

At the climax of Mank, Gary Oldman delivers a tour-de-force monologue during a dinner-party sequence that lasts nearly six minutes. How tricky was it to nail that scene?

Messerschmidt: We had a pretty good idea of what the coverage was going to be before we rolled, because we had rehearsed it extensively — we didn’t wait till we rolled the master and then ask, ‘Okay, what do we do next?’ We had three cameras on it, and the operators were all kind of handing off to each other — it’s not really a scene where we could have shot continuous coverage, but fortunately, we had the benefit of cutting away to the other characters, who are in disbelief over what’s happening in front of them.

Fincher: We’d rehearsed the scene for a day — actually, two half-days where we’d run the dialogue and gone through it. Wandering around in front of Gary with a Steadicam didn’t seem like the right approach — we wanted it to feel like a merry-go-round, you know, ‘Oh God, here he comes back around again.’ We knew the direction that the Indy 500 was going to go in, so it was really a question of figuring out where to put the marks on the floor — you know, ‘This is where you’re going to stop and try to light your cigarette in a walk-in fireplace.’

Messerschmidt: We liked the idea of him orbiting around Marion.

She’s also lit to have a special glow, which makes her a focal point of the scene. What were the other logistical challenges of that sequence?

Fincher: Listen, if you ever get to the set and you feel like, ‘We don’t have what we need in order to pull this off,’ then you have totally wasted the entire preproduction phase. The battle’s won in prep. You could easily derail the making of that scene if people lose confidence in what you’re doing. You have two dozen thespians at the table, and you don’t want them thinking, ‘Oh my God, they’re still finding this?’

But that scene with Gary involved a lot — he has to be drunk, yet cogent, and really specific about the points he’s making, but there has to be a degree of subtlety as well as the broad brushstrokes. Also, everyone else at the table is doing silent-movie acting, while he’s performing in this incredibly broad but appropriate style. It’s a really difficult scene to task yourself with, because the audience may be thinking, ‘Why are these people letting this guy talk like this to the richest man in the world?’ And just because all the other actors at the table don’t have lines, it doesn’t mean they’re not properly engaged with what’s going on — you’ve got two dozen other guests who all have to look as if they’re too afraid to enter the roundabout. So if Gary isn’t moving and delivering his dialogue at a clip that’s fast enough, then you do start to wonder why someone wouldn’t interject and try to save him. The first six times we rehearsed that scene, I did get a bit worried; I was looking over at Erik like, ‘Uh oh — maybe we didn’t think this through enough.’ We had to establish the right rhythm for the scene, so that the pauses wouldn’t be long enough for anyone else to really jump in.

“We shot 2.21:1 [to achieve the perspective of] 70mm, 5-perf spherical widescreen. For my money, it’s an aspect ratio that’s wide enough to look good on a 1.78:1 HD monitor and tall enough not to look weird.”

— David Fincher

How do you strike the balance between realism and a more stylized approach on a project like Mank?

Messerschmidt: First you have to evaluate the movie. On a project like this, there’s an element of, ‘Okay, how do we get that classic black-and-white look?’ But I think you first have to ask, ‘What are we making?’ How do you make your decisions reflexive? Previsualization is great, but it’s more about trying to have a clear idea in your head for the visual approach — and I’m not even saying that I did in the beginning! I had anxiety going into the movie. When David first called me about the project, my reaction was, ‘Oh, cool, I get to do a black-and-white movie.’ So I started to think about what a black-and-white movie looks like, and I had naively only considered film noir — because that’s what cinematographers are naturally attracted to. I sent David some images to consider, and he said, ‘Yes, there’s some room for this.’

But as I started to go back and watch more black-and-white films, including some I hadn’t seen for a long time, I immediately realized how narrow-minded my initial inclination was. I got very insecure, and I thought, ‘I have to reevaluate this approach a little bit, and I’m going to have to think about things in terms of the story instead’ — not in the context of how a black-and-white version of that story would be, but in terms of what was actually happening in the scenes. I pulled lots of references: The Night of the Hunter, Rebecca, The Apartment, In Cold Blood, et cetera. The Grapes of Wrath is a movie that takes place in a lot of environments like one of the main settings in Mank. I started pulling more references like that, because Mank is not a gumshoe noir thriller; it is much more varied in theme.

I was worried that I was going to make the wrong choices because I had been seduced by the idea of what I initially thought [the look] should be. I kept asking myself, ‘Is this right? It feels right, but is it stylized enough? Maybe I should go further.’ The fact that it’s a black-and-white movie amplifies that part of the job, but that part of the job is always there — we’re always evaluating our own decisions and trying to figure out what a film is.

“We were consciously trying to avoid overt homage [to Citizen Kane]. What was most terrifying to me is that a movie like this can so easily become a parody.”

— Erik Messerschmidt

What led you to shoot the film in the 2.21:1 aspect ratio? Did you ever consider shooting in an era-appropriate format like 1:37:1 or 1.33?

Fincher: We talked about it…

Messerschmidt: …but it wasn’t a long conversation.

Fincher: When I started out shooting in 4:3, I just could never do it.

Messerschmidt: That ratio changes more than just composition; I think it changes your blocking choices. You can’t really shoot overs. You can’t do shots with perspective. I mean, you can, but it’s not as effective.

Fincher: The ratio we used was decided in preproduction when I thought we were going to put Hearst at one end of the table and that he was going to send Mank to the other end of the table. And then we found out that even in death, William Randolph Hearst continued to flummox us, because he always sat in the middle of the table. But I was thinking initially that we would need 2.21:1 for this 54-foot table.

For the record, we shot 2.21:1 [to achieve the perspective of] 70mm, 5-perf spherical widescreen. For my money, it’s an aspect ratio that’s wide enough to look good on a 1.78:1 HD monitor and tall enough not to look weird. To me, 2.40:1 on a 16:9 monitor feels like there’s too much black on the top and bottom, and 1.78 looks almost like 4:3.

Mank is designed to look as if it was shot during the same era as Citizen Kane. Did you do any scholarly study of Kane to prepare?

Messerschmidt: We were consciously trying to avoid overt homage. What was most terrifying to me is that a movie like this can so easily become a parody. You want to lean on pastiche as opposed to parody, and riding that line is a scary proposition.

Fincher: We were dealing with completely different types of environments than Welles was working with. Citizen Kane has a lot of these mausoleum-like spaces — the Thatcher Memorial Library, and so on. We had to deal with [transforming modern-day] L.A. and doing scenes in the desert — places with buckling wood floors and stucco, or the Paramount backlot, which doesn’t have a straight line in it! A lot of what we were shooting involved sunlight, or dust blowing in from the desert, or cars driving off with cows mooing in a field.

You shot with a custom-designed Red kit — an 8K Ranger camera with a black-and-white Helium sensor. Did you ever consider shooting with a color sensor and converting to black-and-white?

Messerschmidt: Initially I was thinking that we might find some advantages to having color in the negative — that it could possibly help us in the digital intermediate, and that we might miss the ability to key certain colors and adjust their individual tone. We tested a color sensor, a regular Red Helium, against the monochrome Helium, and the monochrome was clearly the better option. This was long before the conversation about light sensitivity and the benefit of added speed for our deep-focus work. The monochrome sensor is much faster. We rated the camera at 3,200. It’s really clean at 1,600, but we actually liked the look of the noise we got at 3,200 — we liked the texture of it. It was an easy choice.

One aesthetic strategy Mank shares with Kane was the use of higher T-stops to achieve deep focus.

Messerschmidt: In that regard, our approach wasn’t so much about Citizen Kane as it was about how we saw black-and-white looking the best and making it relevant to what we were trying to do. Because we didn’t have the luxury of color separation, using higher stops helped describe depth. We needed texture, we needed bite, and we needed to see the spaces; we couldn’t have everything collapse into muddy, soft, ethereal backgrounds. That just wouldn’t have worked as well, especially when you’re trying to describe depth and use it as a compositional tool.

What made you choose Leitz Summilux-C lenses?

Messerschmidt: I did a lot of tests, and one of the tests we were looking at was resolution and sharpness at deep stops. It gets quite difficult to judge actualized depth of field at those higher stops. What was quite easy to judge was lens resolution at those stops. Lenses really start to fall apart across the board at T11 due to refraction, so 11 started to feel like the ideal stop — we knew that we could be there and get the depth we wanted without sacrificing too much resolution. A lot of how we solve that is through filtration tools, of course.

But it started by just projecting the lenses. The Summilux-Cs, the [Arri/Zeiss] Master Primes and the [Panavision] Primo 70s all produce 200-plus line pairs of resolution at T2.8. But if you go to T16, they’re all sub-70 line pairs of resolution. So it’s a pretty drastic shift.

Fincher: There’s no point in shooting at T11 on a 40mm [full-frame] sensor, because you’re kind of working against yourself. So we knew we would be using a 30mm [Super 35] sensor, and what the stops would be. Then it was just trial and error, but we kept coming back to Summilux-Cs because they’re sort of a perfect collection device; they don’t have a lot of anomalies and they’re flat.

Messerschmidt: The other thing that was a surprise to me is that the Summilux-C’s iris is physically smaller, in terms of diameter at a stop of T11, than a Master Prime or a Primo 70. So your apparent depth of field is greater, because your actual f-stop for a given T-stop is smaller. In actual, objective experience, a T8 on the Summilux-Cs has the same apparent depth of field as a T11 or T11.5 on a Primo 70. So it was kind of an empirical choice, more than anything.

“A lot of the look of the bungalow scenes is due to the fact that we were lighting from outside the room.”

— David Fincher

In terms of lighting, can you describe the overarching idea behind the use of practicals in the frame? Throughout the movie, you have these wonderful atomic-hot practicals scattered around in the backgrounds, even in daylight scenes — like the scene where Marion and Mank reunite on a movie location with the big brute arcs behind them.

Messerschmidt: The movie is grounded in realism, and I just think it always looks better that way — if you start with that and try to get the look as close as possible to how things might look or be lit in those situations. I think if [Citizen Kane cinematographer] Gregg Toland [ASC] had had the technology to light with practicals and keep scenes exposed, he would have done it as well.

There is not a lot of off-camera lighting in Mank. I thought it would be cool if the bungalow scenes were more modern in terms of technique than the flashback sequences, which have a bit more classic style in them, in terms of how they’re lit and how the contrast in those shots is rendered. A lot of the look in the bungalow scenes is due to the fact that we were lighting from outside the room, and we were using practicals at night. There’s a lot of toplight in those scenes, and it’s not as sculpted as classic, period black-and-white.

Putting practicals in the frame may just come down to taste — it just seemed to make sense.

In a movie where many modern methods were used to create a vintage look, the day-for-night walk-and-talk between Mank and Marion at San Simeon stands out as a more classical technique.

Messerschmidt: That was fun. There were some things I was worried about. For example, we put the brightest bulbs we possibly could find in our practicals — I think they were 800-watt metal halides. They had atrocious color, but that didn’t matter for our purposes; we were just hoping to strike the right balance. I remember not sleeping the night before we shot that scene because I was so worried it would be cloudy when we got to the location. We built some LUTs in advance, and shot some tests with the actors. But we were putting so much frontlight on Gary and Amanda, just to get some exposure, that Gary pulled me aside during the test and said, ‘This is a challenge. I’m not sure I can do this with so much light shining in my face.’ We had some special contact lenses made for them so they wouldn’t look like chipmunks from squinting.

When you shoot scenes like that, you always wonder if people will notice. Most people do notice, so it feels good when someone seems surprised and says, ‘Wait — you shot that day-for-night?’ I’m glad we did it that way, because if we had just lit it while shooting at night, the sequence wouldn’t truly convey the full scope of the Hearst estate, and the audience wouldn’t appreciate how big the space was.

“I think cinematographers are often

over-credited for the way a movie looks, and under-credited for the way the story is told.”

— Erik Messerschmidt

How did using HDR impact the production?

Messerschmidt: There’s monitoring in HDR and finishing in HDR, and those are different conversations. After working in HDR several times now, I’ve come to the conclusion that monitoring in SDR and finishing in HDR is a little bit like shooting film, but exposing it based on the video tap. I can look at a waveform monitor, I can look at false color, or I can look at a histogram and figure out where the optimal exposure is in terms of protecting it, but I cannot judge contrast ratios in SDR if I’m finishing in HDR. I can only judge contrast on HDR monitors.

From a more creative, philosophical standpoint, it meant that we could really exploit the sensor and the camera. We could push the contrast more when we wanted to, we could embrace the highlights, and we could block for it. When we were shooting day-for-night, we could look at that day-for-night look and see how bright those practicals could actually be, or how far we could get away with the backlight on Gary’s head so that the audience would actually buy it. In the end, the film looks very close to what it looked like on set, which is comforting.

David, what do you see as the primary advantage of digital filmmaking?

Fincher: Well, there’s the science of it and there’s the taste of it, but my entire existence has been about taking the voodoo out of [the creative process]. The nerds get on these rants about which sensor or which piece of glass is best, or ‘What’s the optimal ND filtration?’ All of that stuff is interesting and good, but digital acquisition for me is about having a 27-inch or 32-inch monitor where everyone can see what we’re making. We can see the frame lines, or how the makeup looks. We’re finally on the same page.

How do you evaluate a cinematographer’s contributions to a given project, Erik?

Messerschmidt: I think cinematographers are often over-credited for the way a movie looks, and under-credited for the way the story is told — conversely, production and costume designers are often under-credited for their work. I think cinematography has a lot in common with editing. We take physical action into a three-dimensional space and figure out how to transform it into two dimensions the audience can understand. That part of the process is so interesting to me — particularly on a movie like this, where the filmmaking is very structured. We’re not just shooting on long lenses and handing what we get to the editor; we have specific intentions for the sequences and how they might be cut together. We have lots of takes, and the editor, Kirk Baxter, gets to take all of that material and distill it down into something remarkable.

What I enjoy most happens in those conversations we have after the table read, or after blocking rehearsal, in terms of how we’re going to break a scene apart, or where the sun’s going to be, or how we’re going to use focus to tell the story, or when we’re going to pan the camera deliberately to reveal somebody in the room to say a line. Some of those conversations may have nothing to do with the look of the film, but they have everything to do with how the audience experiences the film. I think all of those things are under-discussed in terms of what cinematography really is.

AC associate publisher and web director David E. Williams also contributed to this interview.

AC has covered Fincher's previous feature films including Alien3, The Game, Fight Club and Zodiac.

Messerschmidt was recently interviewed for our Clubhouse Conversations series regarding their collaboration on the series Mindhunter.

Messerschmidt and Fincher were subsequently interviewed by Caleb Deschanel, ASC and elaborated on their Mank collaboration in this 84-minute Clubhouse Conversations episode: