Beyond The Frame: Casino

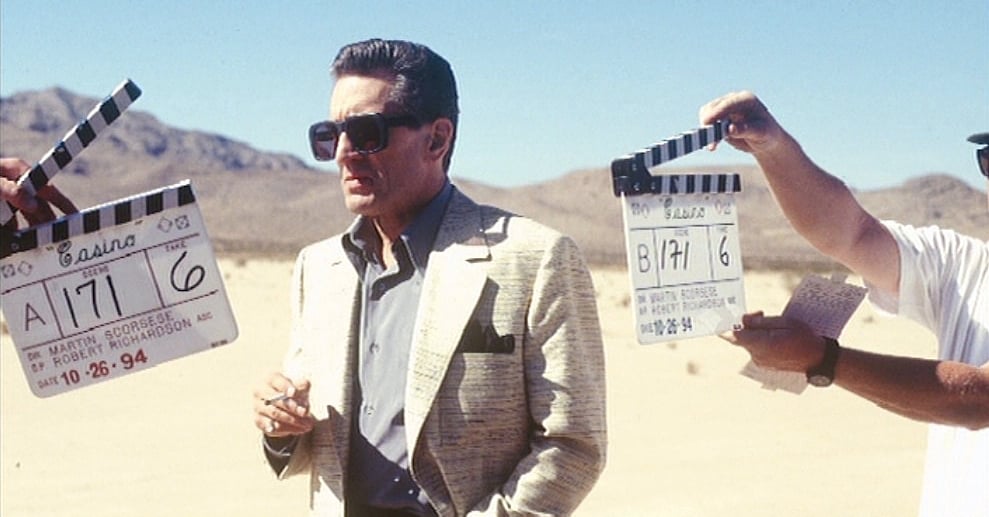

Robert Richardson, ASC solves problems out in the desert with director Martin Scorsese.

For his sprawling and ambitious Vegas crime epic Casino (1995), director Martin Scorsese convened an accomplished group of artisans, including cinematographer Robert Richardson, ASC and his crack crew (gaffer Ian Kincaid, key grip Chris Centrella and first camera operator Don Thorin, Jr.), as well as production designer Dante Ferretti and costume designers Rita Ryack and John Dunn. Also on hand were a pair of seasoned Scorsese regulars, editor Thelma Schoonmaker and assistant director Joe Reidy.

A period piece set in the flamboyant Seventies, Casino relates the tale of Sam "Ace" Rothstein (Robert De Niro), an expert handicapper who enters the upper echelons of the Las Vegas crime world when he is selected by the Mafia to head a cash-rich gambling concern. Accompanying Rothstein during his rise is his lifelong friend, mob muscleman Nicky Santoro (Joe Pesci). Here, Ace and Nicky have a memorable meeting in the desert, far outside the Vegas city limits. Also pictured are Richardson and Scorsese at the camera. The filmmakers would later re-team on Bringing Out the Dead (1999), The Aviator (2004), the documentary Shine a Light (2008), Shutter Island (2010) and Hugo (2011).

Film buffs will note the reccurrence of themes — the exhilaration of power and the inevitability of betrayal, fueled by almost fetishistic fixations — that Scorsese has explored in past films such as Mean Streets (1973), Taxi Driver (1976), Raging Bull (1980), The King of Comedy (1983) and especially GoodFellas (1990). Casino also encores a few stylistic techniques that were used to great effect in GoodFellas, such as freeze-frames, flashbacks, extremely rapid dolly moves and expansive voice-overs by various characters. While Scorsese concedes that his new film bears a superficial resemblance to some of his past pictures, he maintains that Casino is a tale with considerably greater scope. "There are certainly some similarities to GoodFellas in the way the story is told," Scorsese told American Cinematographer editor Stephen Pizzello. "But then, Nick Pileggi and I also wrote GoodFellas, Pesci and De Niro were in that film, and Casino deals with a comparable subject matter. When you have the same writers, the same actors, and similar themes, you're quite naturally going to have some parallels in style. Because this film covers a number of years, we used the voice-over narration to carry the viewer through, and there are also a lot of quick cuts in many scenes. But this film is different than GoodFellas because we have a much larger canvas this time: it's America, it's Vegas, it's the mob out West! There are over 289 scenes, so it's a much bigger picture than my previous films."

The picture was Richardson's first use of the Super 35 format, for which he had mixed feelings. "I was a bit hesitant because Super 35 forces you to have a reduced-quality negative at the final stage," he told AC. "It's an entirely optical process — a blow-up from the first frame to the last. From what I've seen, I'm happy with what we've achieved. [At the time of this interview, the cinematographer had not yet seen the completed film.] Furthermore, the primary reason why I didn't press to use anamorphic was that Martin's shots often require an adjustment on a zoom during the shot. To shoot anamorphic with a zoom was impossible at the lighting levels I wanted to work at — from T2.8 to T4. I also wanted to shoot Kodak's 5393 or 5248 whenever I possibly could because of the blow-up process."

Shooting with Panavision Gold and Platinum cameras, Richardson relied on Primo lenses, particularly the 4:1 zoom. In addition, he carried 11:1 and 3:1 zooms. "Using the Primos in Super 35 was strange for me, because I'm so accustomed to seeing [the widescreen 2.40:1 format] shot with either C- or E-series lenses in anamorphic.The 4:1 was really our workhorse lens; a good three-quarters of the film was shot with that zoom. Once I started it as a primary lens, I preferred to stay in its quality range. When you start off with something, it's wise to stay with it, because the limitations or strengths of the lens you're using become relative throughout the picture. I prefer to stay away from anything that would help you see the difference between lenses unless it's deliberate."

The desert scene featuring DeNiro and Pesci seen here was shot with two cameras, as were many others in the picture. "My initial plan there was to use backlight," Richardson told AC. "Because I knew we'd have daylight that approximates noon all day, from 9 a.m. to 4 p.m. The light is very steep. I was hoping to use backlight as much as we could and then cover the characters for the remainder of the sequences. But by the time we got into this sequence with Bob and Joe, I realized that Martin wanted to cover both actors simultaneously to catch the improvisation. So we went with hard, direct light instead — backlight on Joe and and hard frontal light on Bob. The result was a far more saturated visual look, pulling and using the blues of the desert skin strong contrast to the almost white, dry-lake feel of the landscape."

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.