Beyond The Frame: Rosemary’s Baby

William A. Fraker, ASC, BSC brings the perfect photographic approach to director Roman Polanski's horror classic.

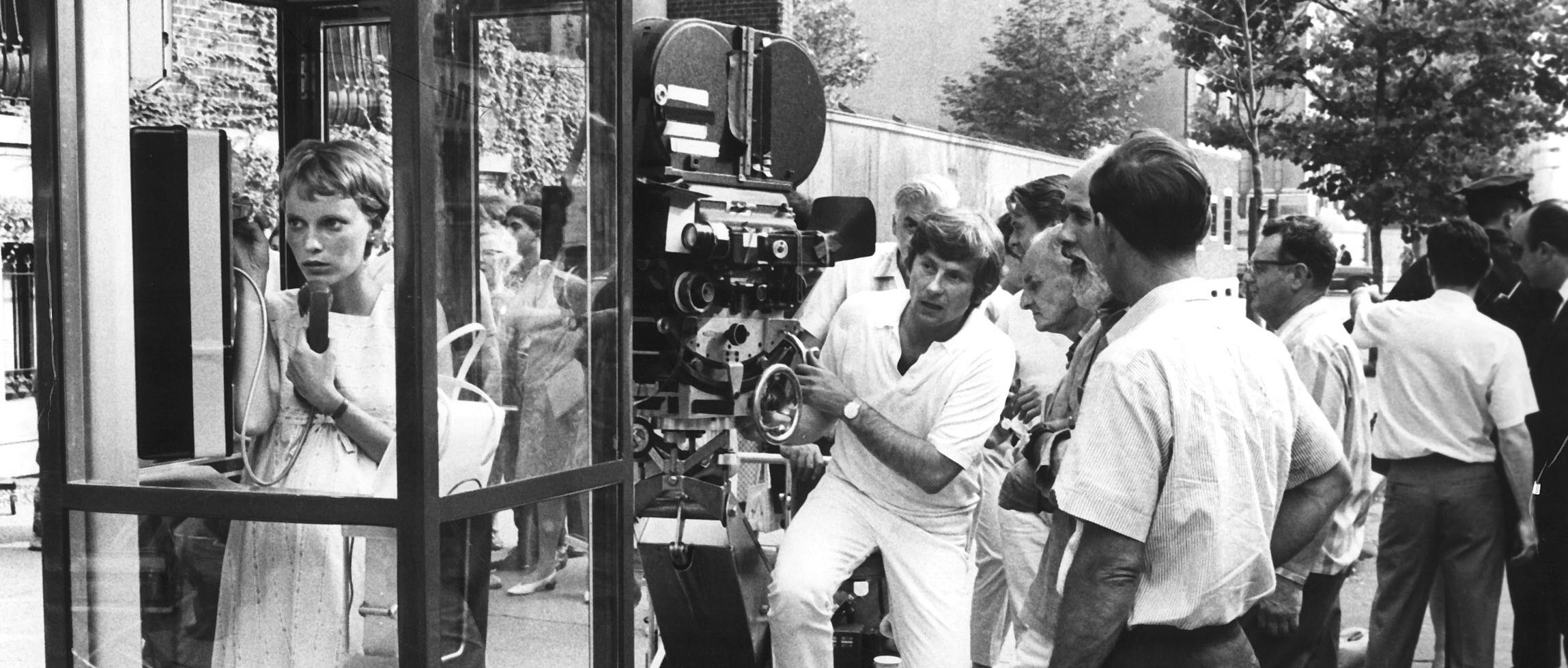

In midtown Manhattan and suffering from paranoid panic, a very pregnant Rosemary Woodhouse (Mia Farrow) prepares to make an emergency call to her obstetrician as director Roman Polanski (at camera) and cinematographer William A. Fraker, ASC, BSC (partially obscured) plot their coverage for this scene from the fright classic Rosemary’s Baby (1968). The tension of the sequence is briefly broken by a humorous cameo featuring producer William Castle as a man who also needs to make a call:

Adapted by Polanski from Ira Levin’s novel, Rosemary’s Baby follows the plight of a modern young woman as she falls prey to a Santanic cult that conspires with her impish husband Guy (John Cassavetes) to impregnate her with the Devil’s son.

Though the picture could have easily seemed over-the-top and campy, Polanski’s sly use of restraint helped make the picture a classic. “Roman is one of the greatest storytellers I’ve worked with, and he really knew how to control and lead the audience — to make them squirm in their seats,” Fraker told American Cinematographer. “And he used suggestion to do a lot of it. His earlier films, Repulsion and Cul-De-Sac, had very little actual violence in them, but they were horrifying. That’s part of the trip, and Roman knew how to do that dramatically through the acting and the dialogue. When you’re a cinematographer, you have to do it visually, with the lighting and the camera.”

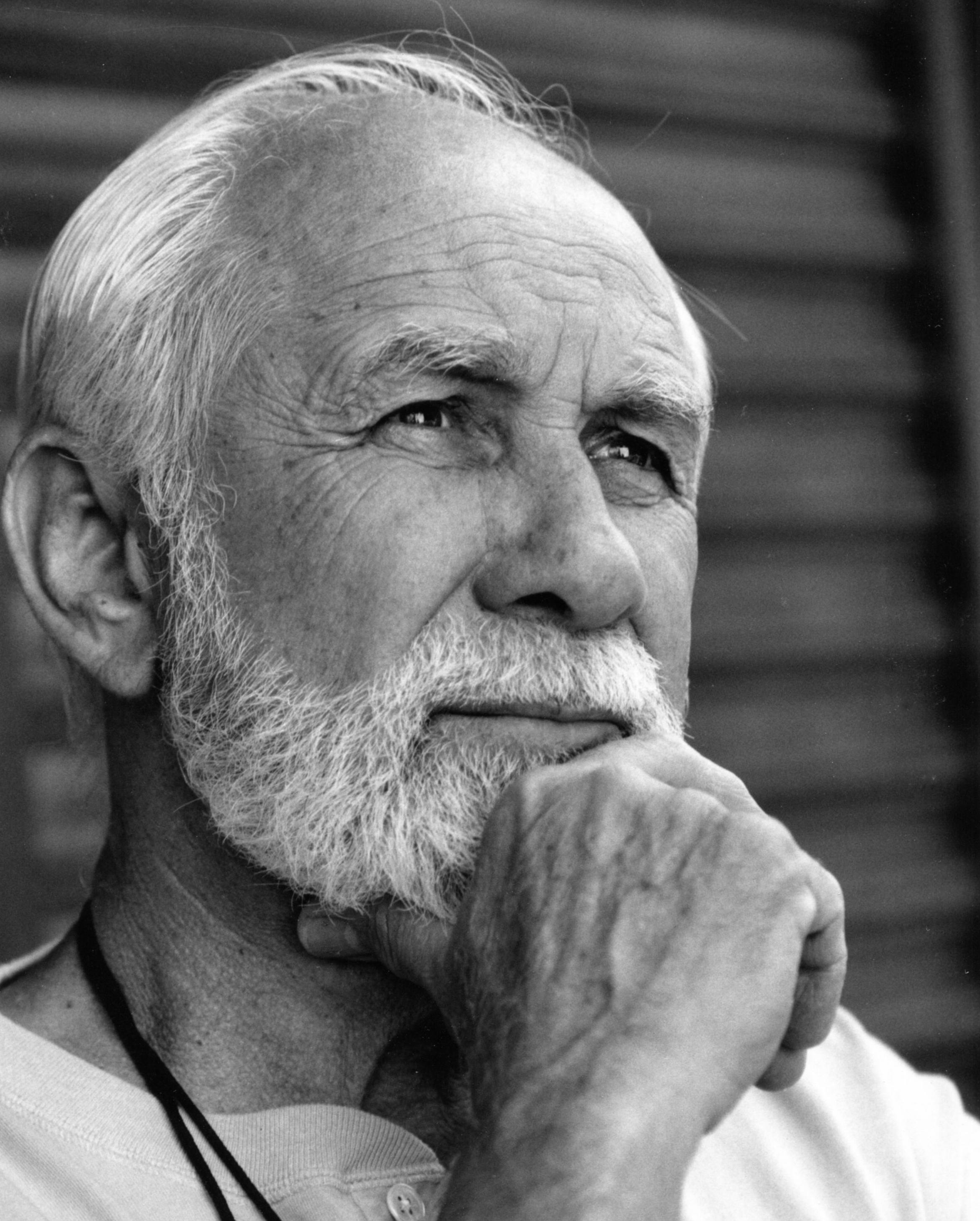

Speaking to AC about his collaboration with Fraker, Polanski recalled that the cinematographer was recommended to him by Robert Evans, then the head of Paramount Pictures, and production designer Richard Sylbert. “Dick knew that Billy was someone to watch,” said Polanski, adding that Fraker “very much enjoyed the freedom Robert Evans gave us.” Polanski recalled that Fraker had just finished a stint at Universal Studios that had been very restrictive, and as a result of that experience, the cinematographer fretted quite a bit at the beginning of the Rosemary’s Baby shoot. Polanski said he teased Fraker about his white hair, telling him, “Don’t worry.”

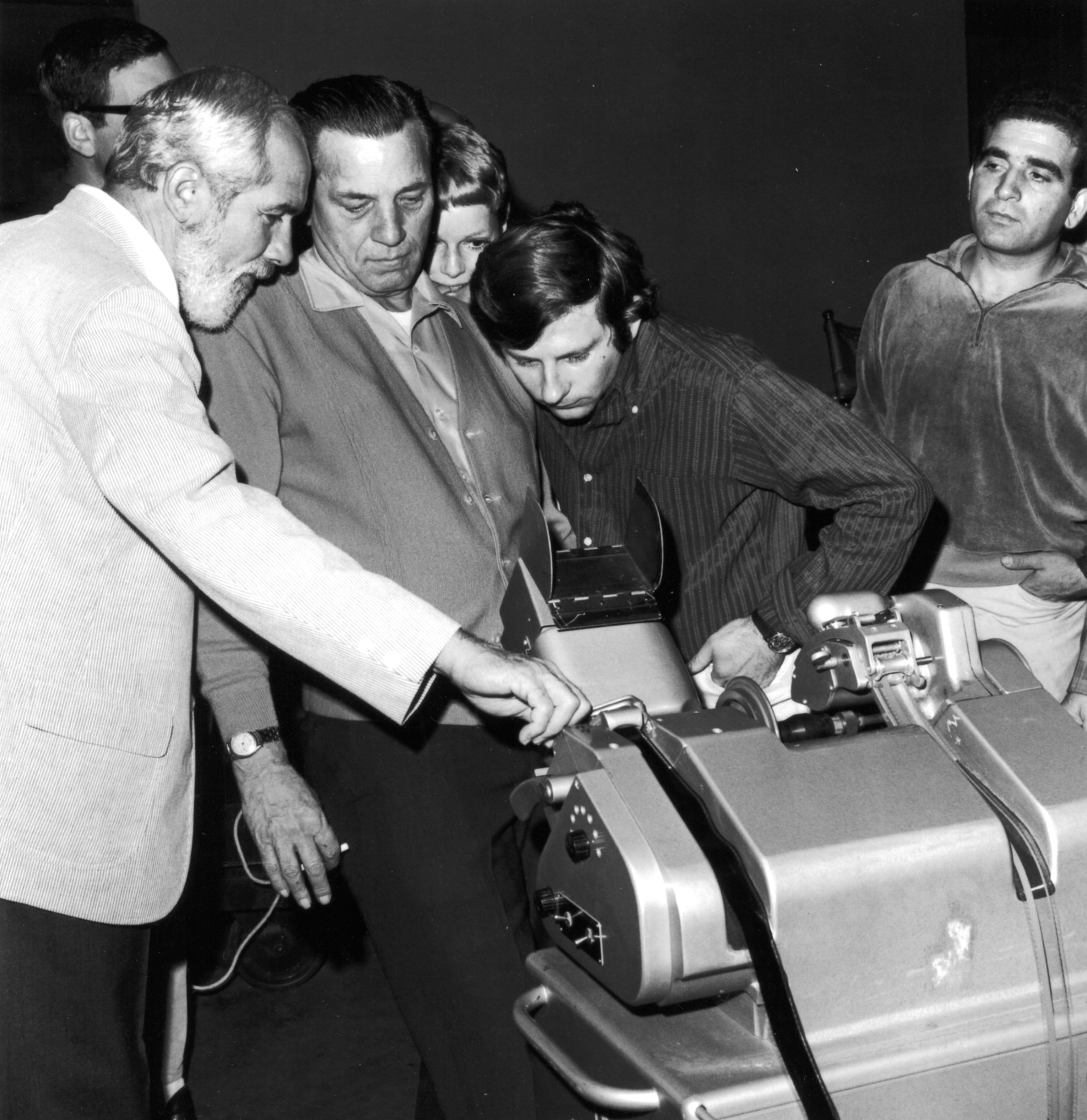

Fraker cites this collaboration with Polanski as a formative experience. He remembers staging a scene in the Woodhouse apartment set in which duplicitous Satanic mastermind Minnie Castevet (played by the diminutive Ruth Gordon) is told that Rosemary is pregnant. Gordon leaves the living room and enters a bedroom where she telephones another coven members with the good news. To represent Rosemary’s POV, Fraker initially framed the shot on Gordon through a doorway, seated on the edge of the bed in full view, but Polanski insisted on a different approach. He only wanted the audience to see a portion of Gordon, and not see the phone at all:

Fraker remembered, “I didn’t get it until we were in dailies and I saw everyone leaning in their seats, trying to look around the edge of the door frame to see what was happening.”

Polanski recalled that one of the objectives on Rosemary’s Baby was to create “depth, not just a flat field” via composition and camera placement. He explained, “If you use composition in such a way that things are hidden from your camera, you can discover something that was hidden when you move sideways, particularly if you use wider lenses, where you come close to the object in the foreground. That was the sort of thing that I was trying to do on Rosemary’s Baby, more so than on my previous films. Since then I have learned a lot, but these things were relatively new for me then.”

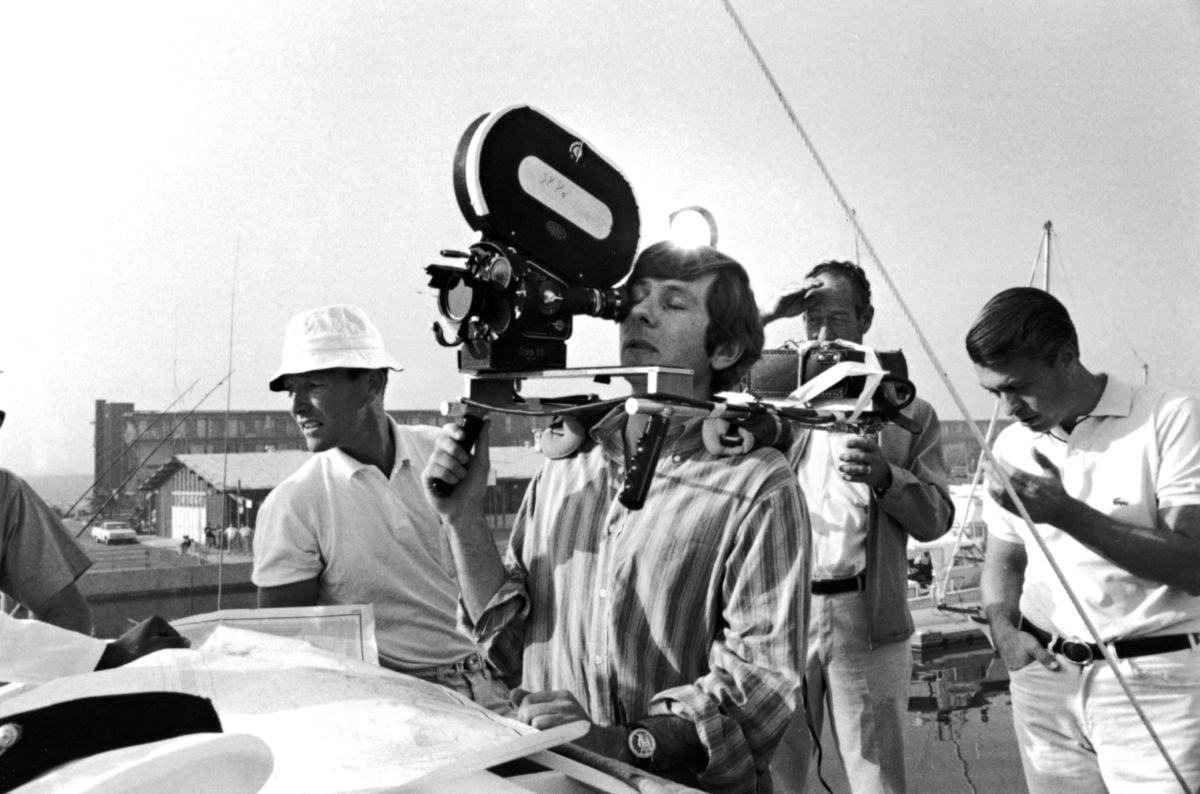

The picture opens with a shot panning across the New York City skyline, which becomes a vertigo-inspiring high-angle view of the rambling Dakota Apartments, and tilts even further down to find the Woodhouses arriving to inspect their potential new home:

“That was a tough shot because it was done from the top of the building across from the Dakota,” Fraker recalled, explaining that a special extended platform had to be built off the rooftop to allow the camera to be far enough out to look straight down on Farrow and Cassavettes far below. “For the first take, we tied a rope around the operator, David Walsh, and he crawled out on the platform and did the shot. After he came back, I asked him, ‘Did you get it?’ He just looked at me and said, ‘I don’t know.’ The height was just too much for him, especially as the shot ended looking straight down. So I tied the rope around myself and did a second take. After Roman called cut, he asked me if I got it, and all I could say was, “I don’t know.’ So Roman tied himself off and operated the shot. Afterwards, I asked him if he got it, and he said, “Billy, I don’t know.’ I still have no idea whose take is in the film.”

With the exception of this opening shot, the entire film was photographed with either a 18mm or 25mm lens, which adds a subtle level of consistency to the imagery, as well as gave Fraker the opportunity to fully capture Sylbert’s impressive sets depicting the Woodhouse’s apartment. “Dick Sylbert’s sets were amazing,” Fraker said. “They were completely wild, so we could shoot from anywhere, and the walls were held together with these metal catches so they could be taken apart and put back together without damage.” He adds that because of the wide lenses, lighting could not be done from the floor, and that the 20’ walls prohibited anything but toplight from the overhead grid, so a system of extendible lamp supports (dubbed “trombones”) was created, allowing Fraker to attach lamps to the walls themselves and raise and lower his sources so they would be just off camera.

Operator David Walsh later told AC, “Roman had come out of making films in Europe, which was considerably different from how Hollywood films were made. One of our first days shooting was a handheld shot walking Mia down the corridor of the apartment. On a woman, especially a star, you typically don’t want to use a wide-angle because it makes her face look bulbous. So we put on a 40mm lens and some diffusion and walked the stand-in up and down. Billy showed Roman, and Roman said, ‘No, no, no, Billy, I don’t want those lenses. I want a very wide-angle lens.’ Billy said, ‘But we’re shooting the star here. Why do you want wide-angle?’ Roman said, ‘Because I want the apartment to be another character in the story. I want it to always be overwhelming Rosemary, to have it even curve, if we can do that, so the walls are enveloping her.’ Billy and I looked at each other, and we were both thinking, ‘That’s really smart. Why didn’t we think of that?’

A lot of cameramen probably would have argued with Roman, but Billy always said, ‘The director comes first,’ and he’d do whatever he could to give the director what he wanted. Roman and Billy were just peas in a pod. They both had such dynamic energy. Working with them was one of the great experiences of my life.”

Polanski explained that he, Sylbert and Fraker “shaped” the look of Rosemary’s Baby very informally. “Billy liked Dick very much, and we worked together as a team,” said Polanski. “We would talk over lunch in the cafeteria, or in a restaurant across the street from the Paramount lot. We did not have conferences or meetings; at the time, such things were not required. Now, most movies are done by committee, and the studios want to know about every detail. They want to have meetings and more meetings. In those days, it wasn’t like that. It was more spontaneous.”

Most of the action in the film is set in the apartment Rosemary shares with her husband, and most of the picture was shot on a soundstage. Polanski said he and his collaborators “asked ourselves, ‘What kind of atmosphere can we create?’ We were trying to have a different atmosphere in every room in the apartment, so when you went from room to room, there would be a different light.”

To give the picture’s unsettling nightmare sequences a distinct look, Fraker flashed the film stock to soften the colors and reduce contrast, adding a hazy dreamlike look. The most powerful, in which a scaly Satanic beast assaults the diminutive Rosemary, features a hallucinogenic aura enhanced by photographic effects and process work overseen by Farciot A. Edouart, ASC.

While shooting the film’s final sequence, in which Rosemary sees her demonic child for the first time, Polanski’s belief in restraint — in defying the audience’s expectations — again came into play. Fraker remembers, “We were finishing our shots with Mia Farrow and I asked Roman, ‘When are we going to shoot the close-up of the baby?’ He just smiled at me and said, ‘No Billy, there will be no baby.’ We were going to have a film called Rosemary’s Baby and have no baby?! And that was exactly what he wanted. And he was right! Mia Farrow did it all with the expression of shock we see on her face as she looked at the baby, and then realized that it’s her child and begins to smile and play with it. It’s a marvelous film moment, and Roman led the audience there. Those are the moments that make it gratifying to work in this business.”

Describing Rosemary’s Baby as “a good suspense movie,” Polanski mused that “it was a very interesting time in Hollywood.” Of Fraker, he observed, “Billy was always in a good mood. He had a very good disposition. I’ve worked with many directors of photography, and they are all so different, but I remember Billy as the gentlest.”

Paramount released this new trailer for the film's 50th anniversary in 2018:

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.