Beyond The Frame: Sunset Boulevard

As much a black comedy as it is film noir, this Hollywood-set tale benefits greatly from stylish lighting by John F. Seitz, ASC.

As much a black comedy as it is film noir, Sunset Boulevard (1950) benefits greatly from stylish lighting by John F. Seitz, ASC — who had previously worked with director Billy Wilder on the noir classics Double Indemnity (1944) and Lost Weekend (1945).

In a September 1950 article on Sunset Boulevard, AC editor Herb Lightman observed that Seitz believed “cinematography must exist to tell the screen story, rather than to stand out as a separate artistic entity.”

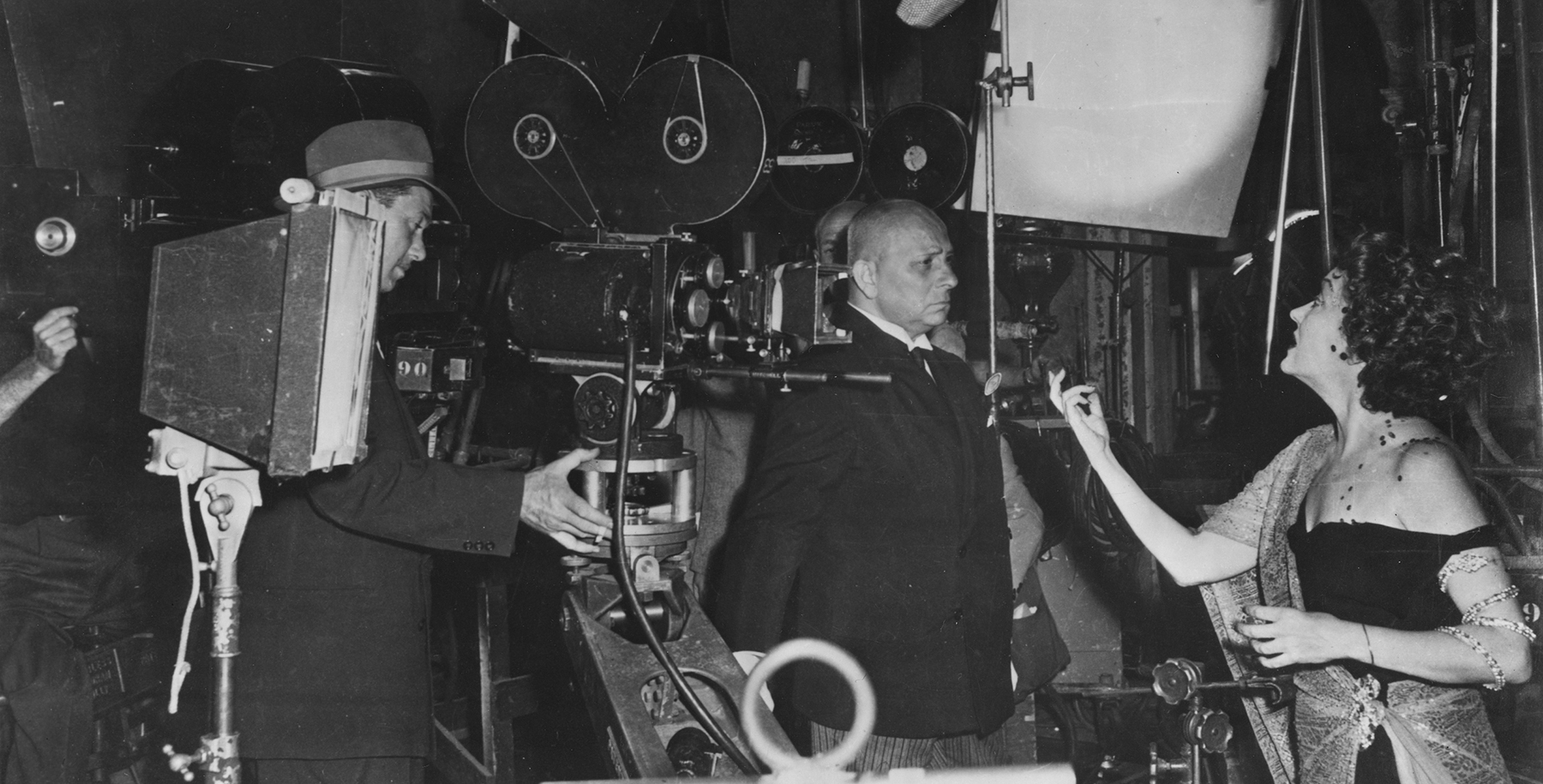

Of note, the film’s sunny, contemporary Hollywood setting is at distinct odds with Seitz’s lighting in Norma Desmond’s decrepit, shadow-fllled Gothic mansion — adding to the notion that the faded silent movie star truly lived in another world, closed off from reality. In this clip, one of the film's most iconic shots, the deranged Desmond (Gloria Swanson) preens for a newsreel camera there to document her arrest for murder, exclaiming “I’m ready for my close-up.”

The film’s Hollywood-set story moves between two planes, and Seitz captures both with cinematography that AC editor Lightman called “honestly realistic, yet suffused with an aura of otherworldliness.”

The everyday world, where Joe Gillis (William Holden) struggles as a screenwriter, is conveyed through documentary-like shots at such locations as the Alto-Nido apartments, the Bel-Air golf course and the Paramount Studios lot. Despite Seitz’s belief that “the least interesting time of the day is noon,” day exteriors often feature the glare of midday sun. They are an effective contrast to the film’s more exotic locale, Desmond’s shadowed, secluded estate.

Seitz’s lighting within her mansion gives only a hint of sun beyond the cluttered walls and creates a suffocating atmosphere. Desmond’s decadent domain is revealed largely through deep-focus shots that keep the vast spaces of her rococo mansion in sharp view.

“To achieve this extreme depth of field,” Lightman explained, “it was necessary to use a greatly intensified light level and to latensify the film in order to stop down the lens aperture sufficiently.” The latensification, which was used for about 15 percent of the film, added perhaps two stops to the film speed. This allowed Seitz to use a practical lamp on the set as the key light in at least one scene. He could also shoot night for night and create, along with other effects, the Gothic gloom of the backyard funeral for Desmond’s pet monkey (a scene that Wilder reportedly described to Seitz as “the usual dead-chimpanzee setup”).

An instant classic, Sunset Boulevard earned 11 Oscar nominations, including a Best Cinematography nod for Seitz. With some 160 credits to his name, dating back to 1916, the cinematographer retired from his career behind the lens in 1960 to focus on his work as an inventor.

Deemed “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant” by the U.S. Library of Congress in 1989, Sunset Boulevard was in the first group of films selected for preservation in the National Film Registry.

Sunset Boulevard was selected as one of the ASC 100 Milestone Films in Cinematography of the 20th Century.