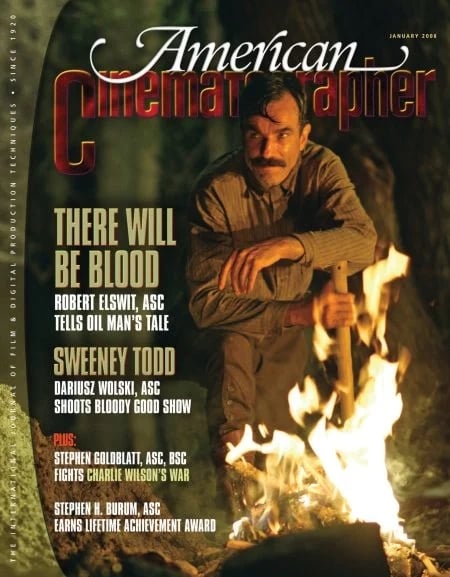

Blood for Oil: There Will Be Blood

Robert Elswit, ASC reteams with director Paul Thomas Anderson on this saga of an unsociable oil prospector who strikes it rich but loses his soul.

Unit photography by Francois Duhamel, SMPSP and Melinda Sue Gordon, SMPSP

There Will Be Blood tells the story of Daniel Plainview (Daniel Day Lewis), a gruff, misanthropic oil prospector plying his trade in the American West at the turn of the 20th century. Using an orphaned boy to disarm potential clients, Plainview takes full advantage of the oil boom, cutting a single-minded swath through untapped gushers in Southern California. Along the way, he clashes with anyone who dares cross him, including a pious small-town preacher, Eli Sunday (Paul Dano), and a man claiming to be Plainview’s half brother, Henry (Kevin O’Connor). Plainview wins most of his battles, but his contempt for others eventually consumes him.

Some might view Plainview as a monster, and, in fact, writer-director Paul Thomas Anderson says he modeled the character partially on an icon of the horror genre: Count Dracula. “I just had it in my head, underneath it all, that we were making a horror film,” he says. “Maybe we go to horror movies because we want to see something horrible happen, in the same way we might get excited to look at a car crash. In some ways, Plainview’s story is a bit like a car crash, one that just keeps getting worse.”

“It’s hard for me not to see Plainview as a little bit heroic — he’s enormously ambitious, and I can sympathize with his quest for survival, particularly during that time in the West.”

— writer-director Paul Thomas Anderson

Nevertheless, Anderson maintains sympathy for his lead character, noting the difficult circumstances pioneering prospectors faced. “A lot of the first oil men started out as gold miners or silver prospectors, and when they made the transition to oil, they were required to be salesmen and speak a lot more than they probably wanted to. I think their natural instinct was to work quietly alone, and I imagine being thrust into situations where they had to sell themselves was endlessly frustrating.

“It’s hard for me not to see Plainview as a little bit heroic — he’s enormously ambitious, and I can sympathize with his quest for survival, particularly during that time in the West,” he adds.

To realize this tale of a driven man who goes off the deep end, Anderson once again tapped cinematographer Robert Elswit, ASC, who had shot all of the director’s previous features: Hard Eight, Boogie Nights, Magnolia and Punch-Drunk Love. Anderson recalls that he first noticed Elswit’s skill while watching Waterland (1992), directed by Stephen Gyllenhall, and the two were eventually introduced by a mutual acquaintance, actor John C. Reilly. “Paul is 20 years younger than me, but I liked him right away,” recalls Elswit, whose recent credits include Michael Clayton and Good Night, and Good Luck (AC Nov. ’05). “He had so much energy and enthusiasm. He also loved some of the same movies I love — particularly films from the ’30s, ’40s and ’50s, many ofwhich are somewhat obscure. Even at 25, Paul was an encyclopedia of American film, and he was very aware of what pictorial style meant. He can respond immediately to something he sees and understands instinctively why it works or why it doesn’t.”

“Paul knows this isn’t the way most people work, but he creates a committed community of filmmakers who understand and respect his process.”

— Robert Elswit, ASC

Pondering his relationship with Elswit, Anderson laughs before offering, “It’s kind of a miracle anything gets done, really. We’ve worked together so long the relationship has its own set of advantages, but it also has enormous dysfunction. Bob and I disagree just as often as we agree, but the relationship wouldn’t be as good if we agreed on everything. Sometimes I’ll sit right over his shoulder and all he’ll want me to do is go away. At other times, we have a great time sitting together and coming up with ideas. Or, sometimes, I’ll get distracted and he’ll put something together that’s really lovely.”

Elswit notes that Anderson’s methods can be quite unorthodox, so much so that the cinematographer has occasionally had to dismiss crewmembers who couldn’t grasp the director’s freewheeling approach to filmmaking. “Paul has very clear ideas, but he doesn’t want to plan out every little thing in advance,” says Elswit. “Actors love him because they feel free to play, create and discover. Cinematographers want to control things as much as we can, but what I’ve learned from Paul is how much better it can be to let accidents happen rather than try to force everything to be a certain way. He wants to see things unfold on the set, and if something isn’t working, he’s willing to stop in his tracks and start all over again. So there’s a constant recharging and renewal of creative energy.

“That way of working is particularly difficult if you’re the focus puller or the dolly grip,” continues Elswit. “Those guys are used to more precise timings and methods. When you work with Paul, you’re shooting with anamorphic lenses and there are no marks on the ground. There is no hair and makeup or wardrobe on set. There are no final touches, there’s no ringing of the bell, there’s no announcement that we’re shooting. There’s also no standard rehearsal, really; once we figure out what the shot will be, there’s a little bit of rehearsal, but then it starts to change and the rehearsal turns into the shooting. It’s a very organic approach, and you have to be ready for immediate changes. That’s why we have the same crew over and over again — Paul has to work with people who are incredibly alert and aware on set. Everyone is truly a filmmaker.”

“I enjoy the technical side of filmmaking, but I’m only able to enjoy it because I have true technicians with me,” admits Anderson, who has no formal film education. “I actually learned a lot of what I know by reading American Cinematographer. Some of the articles could get a bit technical, but that just made me want to learn more. I’m still a bit of a Luddite, though, and I probably think I know a bit more than I do.”

Elswit says he appreciates Anderson’s combination of experimentation and old-school filmmaking principles, qualities that blend to powerful effect in There Will Be Blood. On the technical side, “Paul knew he wanted to make an anamorphic film because he prefers the anamorphic lens system to shooting Super 35mm and doing an anamorphic release print. We did Hard Eight in Super 35, but every movie we’ve done since has been anamorphic. He just likes the look those lenses produce. When you shoot in anamorphic, there’s a different feeling, a different way of staging and different depth of field. Paul loves older films, and those qualities mean something to him.”

The production employed a range of Panavision anamorphic lenses that were modified for the filmmakers by lens designer Dan Sasaki, who has since joined A&S Precision to create lenses for Dalsa Digital Cinema. Elswit’s primary lenses were C-Series lenses Sasaki had originally prepared for Steven Soderbergh’s Solaris. Additionally, the production used a full set of E-Series lenses; two modified spherical Panavision SP lenses, a 35mm and 55mm whose optics were roughly 40 years old; and a set of Super High Speed lenses (ranging from 35mm to 85mm) whose optics were based on modifications Sasaki had made to another set for Memoirs of a Geisha (AC Jan. ’06).

Sasaki also tricked up a vintage 43mm lens that was built around the optical element of a 1910 Pathé camera Anderson had bought and used for select scenes in Magnolia. According to Barry “Baz” Idoine, Elswit’s 1st AC, “The C-Series lenses were generally used for interiors that didn’t require high-speed lenses. The Es had lower contrast and resolution than standard Es and a softer look than the modified Cs; that set was often used for exteriors to soften the harsh desert daylight a bit. The Super High Speed lenses were really amazing — they were so fresh from the machine shop they weren’t even anodized. We used those for night sequences, of course, but Bob also used them to capture some dusk sequences that were just phenomenal. The SP lenses were anamorphized by Dan after we’d done some tests with them. The 43mm lens definitely had a vintage look — desaturated, low-contrast, vignetting, and low-resolution.”

Sasaki explains, “The main modifications I made [to the C- and E-Series lenses] involved replacing the old taking lenses with more modern glass, but we also changed the cylinder prescriptions a little to make the lenses flatter. The Es were optimized for maximum fidelity, but we made the Cs more vulnerable to flaring with modifications that would cause the light to scatter a bit more; in some of them, we introduced reflective material, and in others, we removed the anti-reflective coatings from the lenses. Paul didn’t want the flares to look like the kind you might see in a music video; he wanted the controlled, organic look you’d get from a dated lens.

“The 43mm from the Pathé camera was really interesting,” he continues. “Once we removed it from the camera, we added an old cylinder assembly from the 1960s. I have to say, Paul and Robert did some of the most extensive testing I’ve ever seen to nail in a look with the lenses. It was one of the most challenging shows I’ve ever done.”

Elswit notes, “We did six or eight shots with the Pathé lens. One in particular that’s really nice is when Plainview is sitting in a train with baby H.W. You can see color shifts in the corners, where the colors don’t line up precisely. We also did a few wide shots with that lens. It was very low-contrast and tended to vignette optically, especially on a full negative. It wasn’t razor sharp and didn’t have the same micro-contrast modern lenses do, but it was certainly sharp enough if I stopped down. It’s a neat lens, and I’m glad we used it.

“When I shot Good Night, and Good Luck, we had a short schedule that required us to work fast, and we never took the 11:1 zoom off the camera,” he adds. “This show was different because Paul really likes the discipline of the 40mm, the 50mm, the 75mm and the 100mm. He wants to make the movie play out in those sizes, and he understands how that affects staging and design.”

There Will Be Blood is mainly a day-exterior film, which allowed Elswit to take advantage of the anamorphic format while capturing landscapes on location in Marfa, Texas, which doubled for Bakersfield, California. (A few sequences were shot in California at locations that included Mystery Mesa.) In Marfa, production designer Jack Fisk constructed the main sets: a tiny town consisting of simple wooden structures, including a church and the oil derrick that serves as the focal point ofthe action. “We looked at a lot of locations with Jack, but Marfa was the place,” says Elswit. “There aren’t many spots in America where you can stand on top of a hill and see absolutely nothing in all directions. We all loved the quality of the landscape, and the ranch we used had the little railroad the story required. Jack picked a part ofthe ranch that worked perfectly — from the church you could see the railroad, the oil well and the Sunday family’s little ranch house. They were all visually connected, but Paul is an enemy of the obvious, so he didn’t want to [show] that. But Jack laid the place out wonderfully, and the sets were perfectly integrated into the harsh landscape. The structures’ simple stylization and the way they were sighted in relation to the land and each other made the world of the movie seem very believable and real. The interior designs were always based on ideas about story and character, and Jack’s sensitivity to lighting and how it changes throughout the day was the major factor in the planning and placement of the sets. That, in turn, made it easy for us to find interesting and expressive ways to stage and photograph the movie. In my opinion, Jack’s production design was the great contribution to the film.”

Anderson prefers to use the slowest film stocks possible, and Elswit shot There Will Be Blood on Kodak Vision2 50D 5201, which was used for day scenes, and Vision2 200T 5217, used for all night material. “We shot with Vision2 stocks because they’re less contrasty and easier to work with outdoors [than Vision stocks],” says Elswit. “We did nothing fancy — no flashing, no special filters. Paul actually thinks using an 85 filter is bad! I’ve often explained to him that the stocks are designed to work with an 85, but he thinks that’s somehow interfering with the alchemy of Kodak. This time, though, he let me use an 85 when it was appropriate.

“We also print our dailies — with Paul, there’s no digital world,” continues Elswit, adding that Deluxe Laboratories prepared the dailies. “No DVD dailies are made, and there’s no digital intermediate [DI]; everything is photochemical. We’ve never done anything digitally except some visual effects. There are a few digital effects in this film, mostly involving the [creation of multiple] oil wells or the removal of modern elements from the landscape. If you know you’re doing a DI, you can cheat a bit [on set], but you can’t do that when you’re shooting for Paul.”

“I’m either old-fashioned or quite stubborn, or maybe both,” Anderson admits. “But at the moment I don’t really like DIs, and I’m not sure what the advantage to the process is if you’re shooting anamorphic. I have a hard enough time making up my mind about things without going into a DI suite; I don’t think I’d ever get out of there. The process creates too many options, and at any rate, I don’t like the way it looks.”

The authentic look and feel of Blood are a credit to the camera, production-design and costume departments, but the project also benefited from exhaustive research and carefully considered influences. Anderson based his screenplay on Upton Sinclair’s 1927 novel Oil!, drawing mainly from the first 150 pages, which he lauds for “incredible descriptions of the oil work at the time, whether it was the details of the drilling or what it would be like to be in charge of a group of 20 or 40 men. The book is set in the 1920s, so we crossed a bit of our research and fudged some dates to put us at the beginning of the oil boom in California.” The story is also partly based on the life of American oil tycoon Edward Doheny, whose former home in Beverly Hills provided the setting for the film’s shocking climax.

Additionally, Anderson and his collaborators visited museums, pored over period photographs and studied old, industrial, silent footage of actual oil crews at work. “An enormous amount of footage was shot back then,” Elswit notes. “We watched all these old-time guys working on wooden rigs, and we could see what early rotary or cable-tool rigs looked like.”

A key cinematic influence was John Huston’s The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948). “I have such love for that film it’s kind of hard to talk about it without gushing,” says Anderson, who chuckles after realizing his pun. “On this film, we were trying to keep things simple — the simplest kinds of frames, the simplest number of shots — and we tried to follow the influence of filmmakers like Huston. The movies of the ’40s are incredibly straightforward. They’re the ones I love the most, really.”

The opening scenes in Blood establish the film’s austere style and tone. In a series of dialogue-free sequences that unspool for 20 minutes, the solitary Plainview is shown working amid harsh and dangerous conditions. The first shots show him pounding away with a pick in a mineshaft, where he discovers a promising cache of oil. “Those scenes were shot in Shaffer, a silver-mine area south of Marfa near the Texas-Mexico border,” says Elswit. “The mines were all dug by hand at the turn of the century, and they aren’t being worked anymore. We found one shaft that was 60 or 70 feet deep, and it was connected at the bottom to a perpendicular tunnel that had been created mechanically in the 1920s or ’30s. We could access the vertical shaft via the horizontal tunnel at the bottom.”

Elswit captured some of the shots in the shaft while dangling from a harness, including a startling overhead view of Day-Lewis falling backwards into the mine, a stunt the actor performed himself. Gaffer Robby Baumgartner details the lighting for this location: “Over the mouth of the shaft, we built a truss rig that supported a combination of 18/12K Arrimax Pars and 6K Pars, maybe two of each. We couldn’t point them straight down for safety reasons because Daniel was directly below at quite a distance.”

A second mine setup, a night sequence in which a worker is killed by a falling drill, was filmed in several pieces. The exterior of the mine was shot on location in Texas, but the action inside the mine was captured within a 40'-tall set built by Fisk and his crew at Mystery Mesa. Baumgartner recalls, “The mine set wasn’t quite as long and narrow as the real mine we’d used earlier; it was a bit wider and a little easier to deal with. It was tented in at the bottom, and we lit it with tungsten units.”

The hazards of oil drilling are spectacularly illustrated when an explosion on Plainview’s derrick creates a flaming geyser that engulfs the wood structure and burns with a malevolent glow. (See sidebar below) According to Elswit, the staging of this sequence was “a nightmare,” and Anderson characterizes that day’s shoot as “insane.” Multiple cameras were deployed to capture the action around the 80'-tall pine derrick built by Fisk’s crew. Four of these were controlled by operators; one was placed in a firebox at the base of the derrick; another was set in a crash box to capture the derrick’s collapse; and others were positioned in spots near the derrick that were too hot for the operators. Elswit explains, “The fire was real, and it involved the effects team igniting a mixture of diesel fuel and gasoline that was controlled with a huge pump. The only digital effect, which was handled by ILM, involved the initial explosion at the top of the derrick. Otherwise, it was all pyro.”

The filmmakers’ original plan was to shoot the burn over two days; the special-effects crew, led by Steve Cremin, would start the fire, extinguish it and then re-stage the burn on the following night with at least two more camera operators on hand. “For the first night, we had designed several long shots that would take Plainview from his tented outdoor office to the derrick, where he would cut the ropes that would allow it to fall over,” says Elswit. “We were also planning to shoot another angle of Plainview from the top [of the derrick] that would carry him to another camera. That was as far as we were supposed to go on night one before putting out the flames. Then, on the second night, we were going to shoot a number of other angles to suggest different points of view, including a more controlled view of the fire from over the actors’ shoulders.

“Steve warned us they might not be able to completely extinguish the fire once it got started,” he continues. “The derrick had been treated, but it had been sitting in the hot sun for months, so it was as dry as tinder. Once Steve and his guys started the fire, they couldn’t completely extinguish the top part of the derrick, which was still smoldering. They were afraid it might collapse on its own, so we had to keep going and stage the collapse on the same night. As a result, we ended up not shooting a lot of angles we’d planned to get. It was frustrating, and I was very angry at the time, but Paul is happy with the sequence. The matching became an issue, though — is it magic hour or is it night? Is the sky blue or black? How do we make all of these shots fit together? We didn’t have a lot of time to finish that sequence, so we couldn’t be as careful about what we did and when.”

Shaking his head at the memory, Elswit adds, “The next night, we had to shoot the reverses of the actors reacting to the big fire, and Paul didn’t want to use any artificial light.” In fact, these reverses were lit with real fire generated by either the powerful flame jet operated by Cremin and his crew or, for certain shots, flamethrower-like devices. Crewmembers were protected from the heat by flame-resistant suits, but the grimaces on the actors’ faces are genuine. “The flames got very, very hot, but that’s how we did it,” says Elswit. “I could have lit those reverses completely artificially, but Paul often doesn’t trust that kind of approach. He said, ‘Oh, no, it will be a lot better if we just set something on fire.’ So when you look at that scene, the color on the actors’ faces is the color of burning gasoline!”

For smaller exterior setups involving campfires, Elswit augmented the look of the real flames with two special flicker units Baumgartner fashioned from aluminum, one measuring roughly 1'x8', and a larger one measuring 2'x4'. These homemade units ran on six circuits to create a varied, organic flicker. Baumgartner explains, “Instead of having just six bulbs flickering, we had 80 bulbs flickering on the smaller unit and 200 on the bigger unit. For the smaller unit, I used clear 15-watt peanut bulbs spaced about an eighth of an inch apart. That created a solid little bank of light flickering on six circuits. It simulated the hardness of a real campfire, but the quantity and proximity of the bulbs created a softer source. We ran the flicker boxes at 100 percent, dimming down each channel 5 or 10 percent to create the flicker. In order to get the right colors, I used a combination of party gels — red, amber and yellow with a touch of green and blue — and cut them in shapes so the light wouldn’t come out in one solid color.”

The movie’s period dictated the use of oil lamps, candles and minimal electricity for interior sequences. “The early scenes in Texas, which were all supposed to be lit with oil lamps, were kept a bit warmer than the later scenes in Signal Hill, where they had electricity,” says Elswit. Baumgartner recalls, “During prep, Bob and I talked about how reading actual candlelight was just too warm, so for those scenes, we couldn’t match all the way down to candlelight. We tried to find a happy medium that simulated the color of candles or lanterns without being too low on the Kelvin scale. We ran some tests where we matched the candlelight at 1800°K, and that was much too warm. So we worked our way up to a level that was warm enough to be realistic, but not so warm that we were too far into the red spectrum. In those situations, we generally wound up at around 2300°K or 2400°K.”

For a number of interior scenes, Elswit used a combination of Lowel Rifa-lites and muslin balls to create floor-light setups. He also used small fixtures inside China balls to create toplight for certain situations, such as the dinner sequences in the Sundays’ house. Baumgartner notes, “Bob is a big fan of the Rifa-lites, which are easy and quick to use. We also used a lot of practical and hard light generated by Tweenies, Inkies and Babies. In some of the China balls, we used three halogen bulbs on a slight flicker to create a bit of movement that would emulate the look of candlelight.”

Elswit explains that for interior scenes, he sought to “build the light level up enough so I could shoot with our 200-ASA stock and not underexpose, working at a T-stop of around 3.2. Things got tricky whenever Daniel was wearing his hat, because I had to somehow light his face under the brim without making it feel completely artificial. I tried to place the light far enough away from him and soften it with diffusion so it would feel like ambient room light. Usually, there was enough ambient light from the small sources in the scenes, like sconces and table lamps, that I could create a soft, directional light that didn’t feel flat. Sometimes I’d use a 2K aimed through muslin and whatever gel we picked. In some of the bigger sets, I just tried to hide a bunch of smaller units.”

One of the more interesting interior setups was the small church where Rev. Sunday preaches to his flock with fire-and-brimstone fervor. Two major sequences take place in the church, one when it’s a humble structure, and another after the reverend has used oil money to expand it.

In the first scene, Plainview watches Sunday perform a writhing, arm-flailing exorcism on an elderly woman. Baumgartner offers, “Bob and Paul really wanted to push the envelope in that setting. The church is supposed to be a very rudimentary structure built with walls constructed entirely of wooden slats, and you could see blown-out sky or landscape in the spaces between the boards. It wasn’t feasible to try to control that, so we had to build up the lighting inside.” To do this, the crew initially rigged four 6K Pars in the rafters, bouncing them into muslins to create a base level of light. Baumgartner notes, however, that “after Bob took a look at the setup during rehearsal, he felt it would be best to remove those units so he would have the freedom to shoot from more angles.” Ultimately, the crew built up the light level by using Arri 18K Fresnels and the punchy Arrimax Pars to push light through the windows and bounce light through the slats. Elswit reflects, “If I’d had a different director, I probably would have added a bit of fill in the corner behind us, which you wouldn’t have seen. It probably would have lifted the shadows, but I probably would have regretted it. As it was, there was never enough light to actually balance the exterior, so the windows just blew out. But we had enough light to shoot at a T3.2 or T3.5, which kept the light from flickering or flaring, and we got extraordinary blacks and a huge amount of contrast.”

The later scene in the church, in which Plainview is forced to kneel before the congregation and confess his sins, takes place in a larger room with a muslin ceiling; the wooden back wall features a large cutout of a cross that allows daylight to pour through the opening. “The muslin ceiling allowed us to justify some daylight,” Elswit explains, “so we mounted a couple of Arrimax Pars on a scissor lift and just pounded light down through the muslin. That’s what created the color of that interior. I tried to make it look as though real sunlight was hitting the muslin. Even though the muslin affected the color temperature, I kept the temperature around 5600°K.”

The film’s climactic scenes, set in Plainview’s mansion, were shot at the Greystone Mansion in Beverly Hills, Doheny’s former home. The unpleasant denouement begins in Plainview’s office, where the embittered mogul confronts his now-adult son, H.W. (Russell Harvard). “That’s the one scene that made me wish we did a DI, because I would have fixed all the windows,” notes Elswit. “We wanted those scenes to be magic hour, and I don’t think I controlled the windows as well as I could have. I wasn’t doing anything unusual; I was just combining ambient light in the room with bounced light from outside the windows. The electric lights in the scene were just accents; they weren’t really lighting anything. Outside the room, I had 18Ks bouncing into muslins with lots of blue gel.”

The cinematographer is happier with the look of the sequence that concludes the film. Set in the mansion’s bowling alley, the scene begins with the drunken Plainview asleep in the gutter — literally — and proceeds as he is awakened by a surprise visitor, Rev. Sunday. To facilitate the shooting of this grotesque tableau, the production refurbished the real bowling alley in Greystone Mansion, a site that had special resonance for Elswit. “That mansion was the headquarters of the American Film Institute when I went to school there,” he recalls. “The bowling alley was a complete wreck back then, but we used it as our soundstage when we were shooting our first-year video projects. The city of Beverly Hills was all too happy to let lack Fisk restore the bowling alley to its original glory. There I was, standing in a place where I’d shot video films as a student. It was very strange.”

Anderson, a fan of Stanley Kubrick’s films, wanted the bowling alley to have a Kubrickian symmetry and menace. “Paul wanted to paint the walls white and turn the room into a white cube, like something out of A Clockwork Orange,” says Elswit. “There’s no character to the lighting at all; it’s just a white box. Paul kept marveling at how Kubrick did things, and I would say, ‘But Paul, Kubrick built sets. He didn’t come walking into a place like this!”’

Detailing the crew’s approach to the scene, Baumgartner explains, “We were seeing floor-to-ceiling and wall-to-wall in there, so we articulated some 212 bulbs to supplement the light coming from the practical globes hanging from the ceiling. We put a pair of 212s on armature wire at each socket so we could just spin the 212s and hide them behind the globes, depending on the camera position. That helped to build up the ambient light to the point where Bob could shoot freely. A portion of that scene happens at the end of the lanes, where the light levels were a bit low, so my best boy, Chris Milani, suggested hiding a row of PH 140 bulbs behind each pin rack. That created a beautiful glow that we used for the whole scene; it also added a vital push of light for the actors.”

Summing up his latest experience with Anderson, Elswit concludes, “Paul knows this isn’t the way most people work, but he creates a committed community of filmmakers who understand and respect his process. He just can’t function any other way. It can be a marvelous way to function, though, and it creates the kinds of scenes and moments you won’t find in any other films.

TECHNICAL SPECS

2.40:1

Anamorphic 35mm Panaflex Platinum, Millennium XL

Panavision C-Series, E-Series, Super High Speed and anamorphized SP lenses; 43mm Pathe lens

Kodak Vision2 50D 5201,200T 5217

Printed on Kodak Vision 2383

Setting an Oil Derrick Ablaze

Before working on There Will Be Blood, special-effects supervisor Steve Cremin had created flaming oil wells for Jarhead — so successfully, in fact, that effects artists at Industrial Light & Magic still use those fire elements as references for other shows. Here is his account of how the flaming geyser was created for a key scene in Paul Thomas Anderson’s period drama:

“We used petroleum products, diesel fuel and gasoline in different proportions depending on the shot. For day scenes, we used a mix that would create more smoke. Smoke doesn’t read at night, but if we wanted some night shots to be brighter, we just changed the mix.

“We made our own jet nozzle to shoot the juice through. The pumps we used were hard to find: high-pressure petroleum-transfer pumps that do a huge volume at huge pressure. They were powered by hydraulic motors, which eliminated the danger of creating sparks anywhere near the fluid. Using an electric pump with metallic parts can throw sparks all over the place, and the impellers aren’t explosion-proof, so you’re taking a heck of a chance with that kind of setup. All our power was remotely activated.

“When you do this kind of stunt, you’re subjected to environmental oversight the whole time. No fuel can be shot through the nozzle unless it’s ignited; you can’t let any fluid hit the ground, because then you’re liable for a toxic spill. Before we shot anything, we had to test the whole area to verify the levels of petroleum in the soil. Once we’d finished the stunt, we had to pull soil samples within a 150-foot radius [of the fuel jet] to prove we hadn’t added petroleum to the soil.

“Because the flames had to ignite on camera, we first ran simulated oil, a water-based non-toxic product that was okay to drop on the ground. That ran through one pump for a certain amount of time, and then we’d inject the other pump and safely follow the water with fuel we could ignite.

“We had four igniters in case any of them failed. They included electronic coils, propane poppers, pyrotechnics and, as our fourth backup, road flares below the deck. If anything shot out of the nozzle and didn’t get lit, it had to go through the flares before it hit the ground.

“The original proposal was to make the derrick out of steel and put a veneer on it that could burn. That would have allowed us to put out the fire and replace the veneer for subsequent takes, but building a steel derrick would have been more expensive and time-consuming. And Paul just prefers guerrilla-filmmaking tactics: ‘Let’s just light it up and go for it.’

“Because the derrick was made of wood, I knew that even if we managed to put the fire out, the structure would smolder through the night and possibly collapse. As it turned out, we picked a night that was about as windy as we could tolerate, and the flames all blew to one side of the derrick. We put water on it and got the flames to go out, but we couldn’t guarantee the derrick would still be there the next day, so we had to keep going to get the shot where it collapses.

“We let the derrick burn for as long as we could before we had to pull it down. The crew kept filming while Paul let the actors try different things; he’s a bit of a renegade, and he wanted to play it out to the bitter end. I was standing behind him while the derrick was crackling and popping, and he kept looking back at me to make sure it was okay to keep going. Finally, I said, ‘It’s time. If we don’t drop it, it’s going to drop on its own.’ He wanted to try one more scene that took about two minutes, and I was sure we were going to lose the derrick. But he finally said, ‘Okay, drop it.’ We had the derrick hooked up to a crane with a couple of cables that allowed us to pull a weak-knee out from under it. It dropped like a dream.

“For reverses of the actors shot the next day, we just lit up our jet nozzle again. All crew members anywhere near the fire wore Nomex fire-protection suits, but the actors were just wearing wardrobe that had been flameproofed. The closest actors were about 120 feet from the fire, but it was still extremely hot at that distance. Trust me, you can’t get close enough to actually get burned because it gets very uncomfortable. My guys probably got within 60 feet of the fire, and they could only stay that close for a short time.”

— Stephen Pizzello

You'll learn much more about Elswit's career and body of work in this profile.