The Old Ultra-Violence: A Clockwork Orange

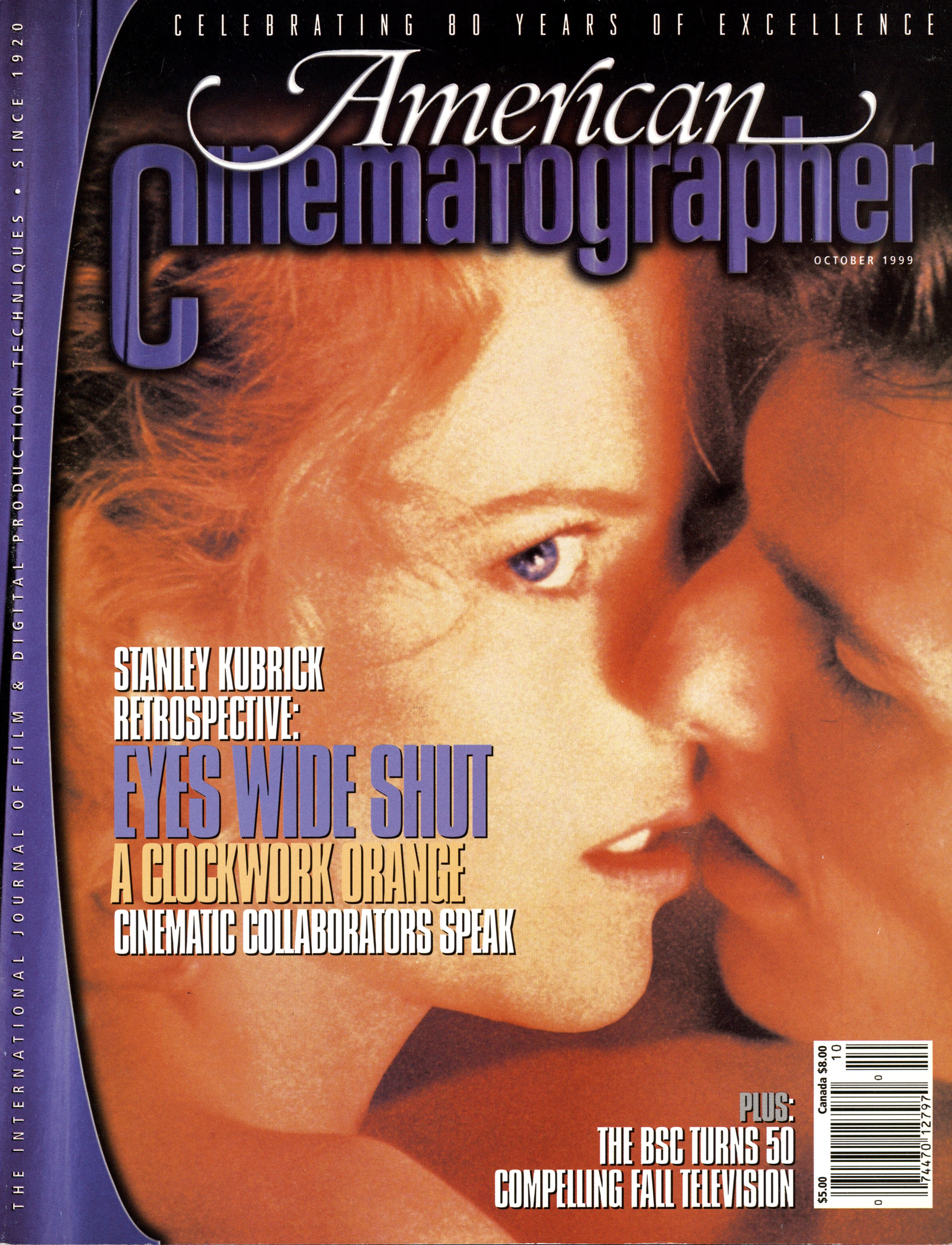

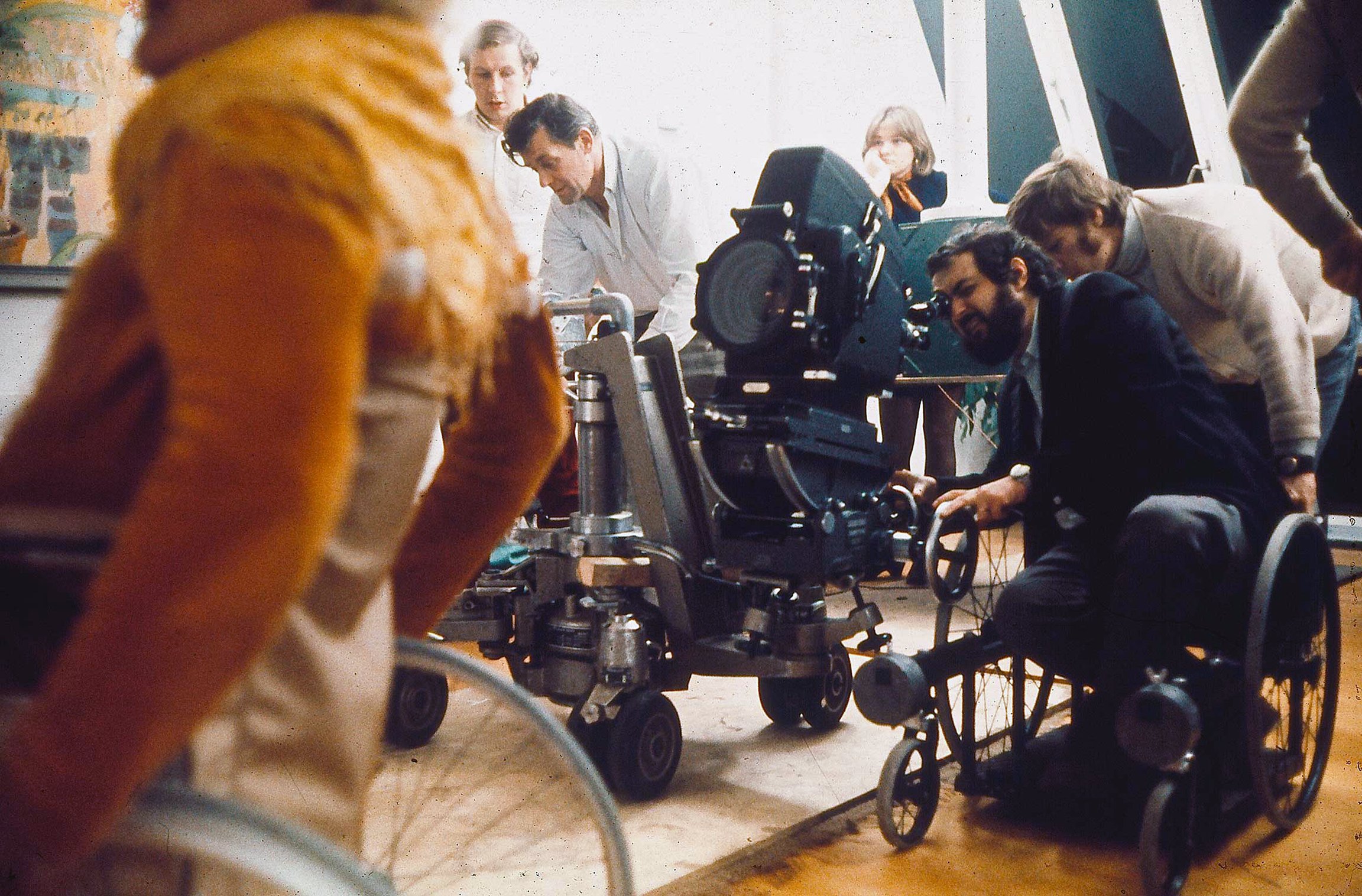

Director Stanley Kubrick enlisted lighting cameraman John Alcott, BSC to help create a bleak dystopian futurescape.

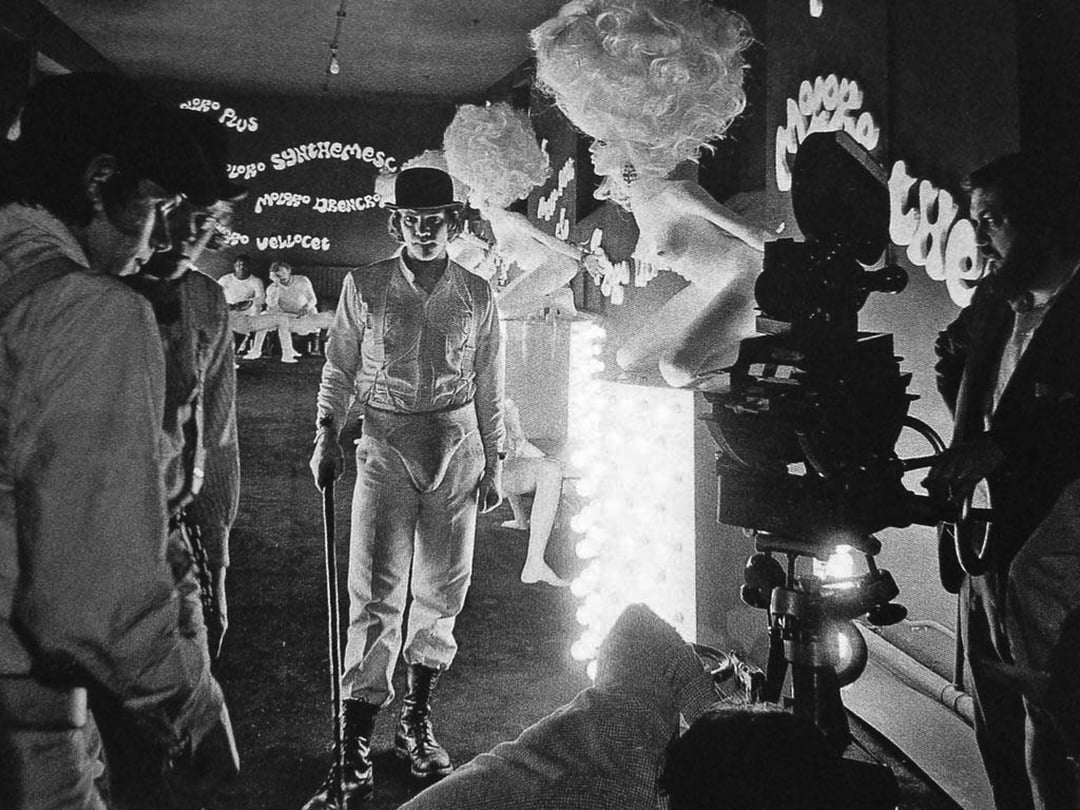

There was me, that is Alex, and my three droogs, that is Pete, Georgie, and Dim, and we sat in the Korova trying to make up our rassoodocks what to do with the evening. The Korova milkbar sold milk-plus — milk plus velocet, synthemsc or drencrom — which is what we were drinking. This would sharpen you up and make you ready for a bit of the old ultra-violence.

— Opening narration

When A Clockwork Orange was released in 1971, the nightmarish near-future world depicted in the film seemed closer to reality than ever. The “free love” mood of the Sixties was officially over. Hippies were being retired and the boils of punk nihilism were beginning to fester. Watergate loomed up ahead, and “sex, drugs and rock ’n’ roll” was the youth culture’s new mantra.

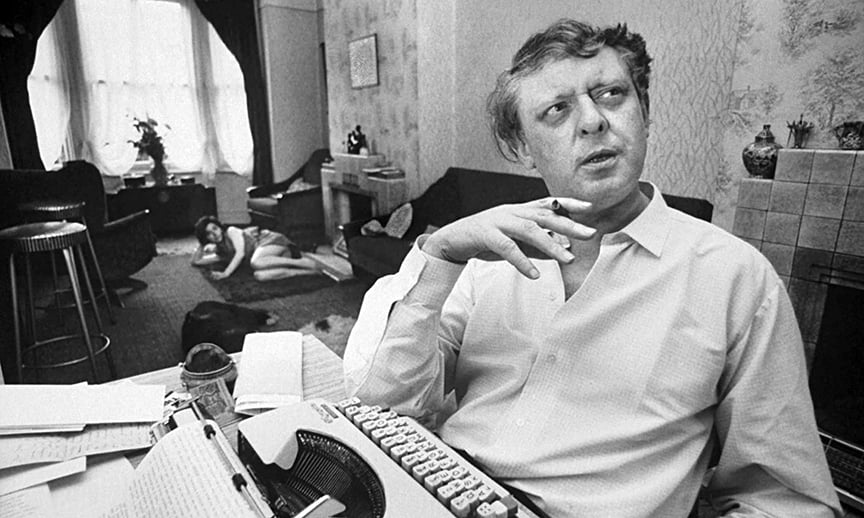

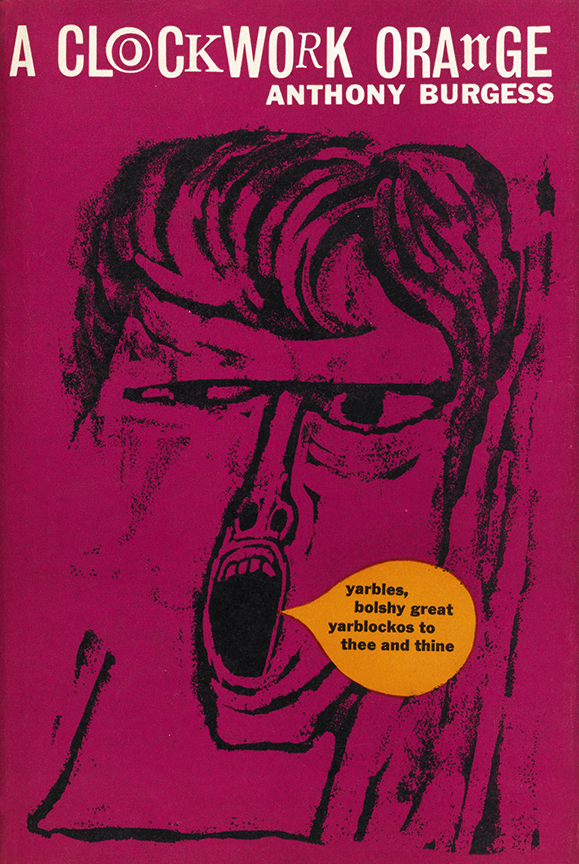

Almost a decade earlier, British author Anthony Burgess had presaged a violent, amoral future with the publication of the 1962 novella upon which director Stanley Kubrick’s notorious film version would be based. A first-person narrative, Clockwork was written in the cryptic lingo of its protagonist, the sociopathic Alex DeLarge (played in the film by Malcolm McDowell), a teenage Beethoven-loving hooligan. He and his trio of criminal cohorts engage in fights, muggings, rape, and other assorted viciousness until our self-described “humble narrator” is convicted of a sadistic murder. After landing in prison, Alex feigns religious salvation and volunteers for an experimental reconditioning cure, under the assurance that he will be released if it proves successful. The “Ludovico Technique” — a Pavlovian-response aversion therapy designed to dampen violent urges — renders Alex incapable of committing new crimes, but its programming also leaves him defenseless when confronted by old enemies. Found and tortured by the deranged writer husband of a woman he had fatally attacked, Alex is transformed into a cause célèbre by an overzealous media and conniving politicians decrying the inhumanity of his situation. The debate becomes philosophical: should man tamper with human behavior? In the end, Alex is released from the Ludovico spell and again unleashed upon the world.

The Clockwork novella was Burgess’s attempt to deal with and transform a personal tragedy. During World War II, while he was stationed overseas, the writer’s pregnant wife was savagely beaten in London by four American deserters, causing the couple to lose their unborn child. Afterward, the wife attempted suicide and Burgess self-destructively turned to the bottle. His later observations of various street gangs — including their fetishistic dress codes served as additional inspiration. In regard to his work’s oblique title, the author noted, “The book was called A Clockwork Orange for various reasons. I had always loved the Cockney phrase ‘queer as a clockwork orange,’ that being the queerest thing imaginable, and I had saved up the expression for years, hoping someday to use it as a title. When I began to write the book, I saw that this title would be appropriate for a story about the application of Pavlovian, or mechanical, laws to an organism which, like a fruit, was capable of color and sweetness. But I had also served [during the war] in Malaya, where the word for a human being is orang.”

Two years after the publication of A Clockwork Orange, director Stanley Kubrick virtually defined the black-comedy genre with Dr. Strangelove, Or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb, his indictment of the Cold War. A prophetic glimpse into a fatalistic future, the film was ironic, pessimistic, and pristine in its technical perfection. In 1966, screenwriter and novelist Terry Southern, who had collaborated with Kubrick on Strangelove, sent a copy of Clockwork to the filmmaker, who didn’t immediately respond to the proposed project. Southern was so passionate about the cinematic possibilities of the story that he purchased a six-month option on the novella for about $1,000 against a purchase price of $10,000, with percentages to be worked out later. He then wrote an adaptation, which he sent to several producers, including David Puttnam. In order to determine whether the material would be deemed acceptable by the British film censor, Lord Chamberlain, Puttnam and Southern submitted their Clockwork script. It was sent back unopened, with the remark, “I know the book, and there’s no point in reading this script because it involves youthful defiance of authority and we’re not doing that.”

In late 1969, Kubrick finally responded to Southern’s Clockwork suggestion and asked if he still had control of the property. Southern had renewed the yearly option once, but was then unable to pay the $1,000 fee. His lawyer, Si Litvinoff, and friend, Max Raab, had picked up the option. Upon hearing that Kubrick was interested, they sold it to the filmmaker for a hefty profit. Southern said the fee was approximately $75,000, but other sources say Litvinoff and Raab were given $200,000 and a five-percent profit clause, which represented a potential windfall of about $1.2 million. Southern subsequently sent the director his adaptation of the novel and received a letter stating, “Mr. Kubrick has decided to try his own hand.” The filmmaker completed a first draft on May 15, 1970. It was the first time the director had worked alone on a screenplay.

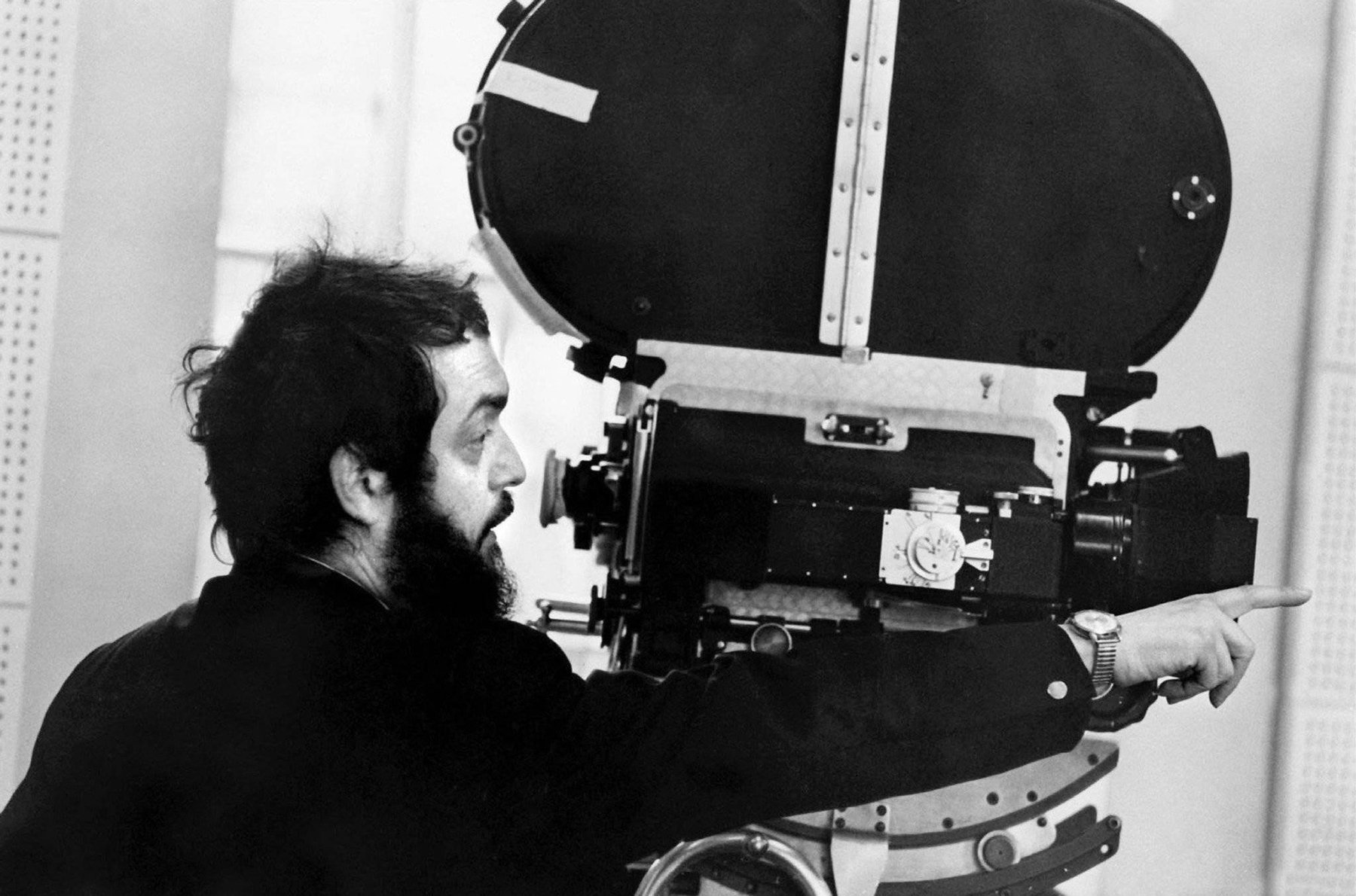

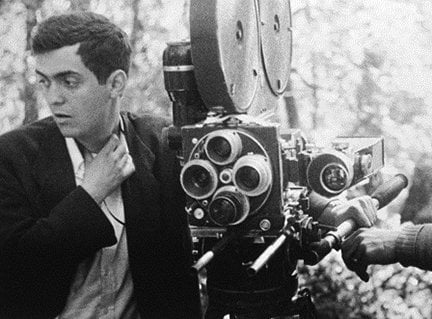

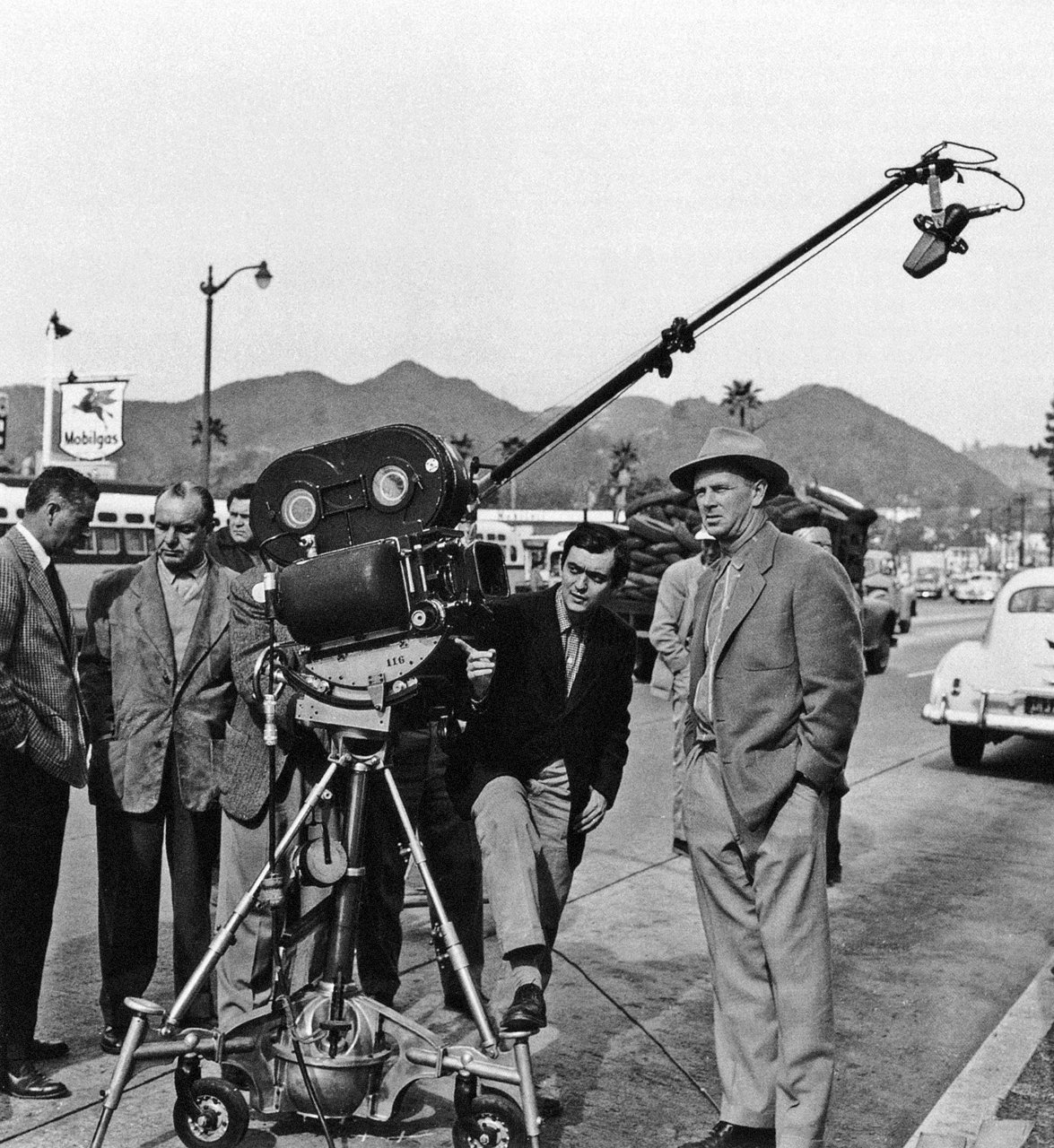

Kubrick was just the man to adapt A Clockwork Orange into a film. He would ultimately create a nasty, violent, and morbidly funny look ahead to the youth culture of the Eighties and Nineties, while delivering the bad but pragmatic news that man can’t really change his nature. At the dawn of the Seventies, Kubrick’s career was in its second decade. During the mid-Forties, he had been a wunderkind still photographer for Look magazine, beginning his association with the publication shortly before he turned 17. In 1951, he became a filmmaker and photographed two shorts, Day of the Fight and Flying Padre. A formidable cameraman, Kubrick continued to photograph his own work on the features Fear and Desire and Killer’s Kiss. However, while making The Killing in 1956, he had his first collaborative relationship with a director of photography — Lucien Ballard, ASC. The situation proved thorny. Ballard was a respected Hollywood veteran who had shot such pictures as The Devil Is a Woman and Crime and Punishment. Kubrick demanded control over every visual detail, including composition and lens choice, and by sheer strength of ego he imposed his will on the seasoned professional. This became a pattern of behavior over the director’s subsequent pictures.

On Paths of Glory, Kubrick hired German cameraman George Krause, who had photographed Man on a Tightrope for Elia Kazan. German rules allowed Kubrick to operate the camera himself, affording him the hands-on control he desired. Spartacus is the only film directed by Kubrick over which he did not have total control of the production. His relationship with Russell Metty, ASC, whose credits included Bringing Up Baby and Touch of Evil, was a disaster for Kubrick, who was not able to impart his vision to the strong-minded director of photography. (Ironically, Metty earned an Academy Award for his expert work; see AC Jan. 1961 and May ’91).

Lolita was shot by Oswald Morris, BSC and Dr. Strangelove was photographed by Gilbert Taylor, BSC. The “English” rules of production, which give the director autonomy over camera operation, allowed Kubrick to select the shots, lenses, and framing on both of these pictures, while the two fine cinematographers executed his lighting plans. Kubrick’s ensuing work with Geoffrey Unsworth, BSC on 2001: A Space Odyssey helped to forge a new era in contemporary cinematography through the reinvention and refinement of special effects techniques that had long been practiced in Hollywood and Britain. Toward the end of the lengthy and involved shooting schedule, however, Unsworth asked to move on to other commitments, and his assistant, John Alcott, took over.

Born in London in 1931, Alcott started out at Gainsborough Studios, where his father was a production manager, and worked as a focus puller on such productions as The Singer Not the Song, Whistle Down the Wind, The Main Attraction and Tamahine. Among the material he shot for 2001 was the “Dawn of Man” sequence, which made extensive use of a unique front-projection system (see AC June 1968).

For A Clockwork Orange, Kubrick promoted Alcott to the key photographic position and gave him the credit of lighting cameraman. “A Clockwork Orange employed a darker, more obviously dramatic type of photography,” Alcott told AC in 1976. “It was a modern story taking place in an advanced period of the 1980s — although the period was never actually pinpointed in the picture. It called for a really cold, stark style of photography.”

Kubrick’s adaptation of the novel is depicted in three segments. In the first, Alex and his gang terrorize the locals with their lust for sex and violence. Next, Alex is imprisoned and selected for the Ludovico treatment. Finally, after his release, Alex’s victims get their revenge, but in the end, Alex’s glee for mayhem returns — man cannot alter his fate. Each of the three sections has a distinctive color palette and camera style that expresses the narrative. To depict Alex’s fondness for “ultra-violence,” Kubrick and Alcott employed a bright color presentation with high-key lighting, fluid zooms, and dolly shots. Alex’s time in prison and reprogramming is rendered in cool, flat tones, as long takes and subtle camera moves create a somber and then clinical atmosphere. The last segment returns to the environment of the first, but is rendered in gray and low-key tones. Flatter lighting and desaturated colors help to define Alex’s comeuppance.

Understanding that filmmaking is as much a mechanical craft as it is an artistic endeavor, Kubrick has always kept abreast of technical innovations which he could possibly implement in his productions. However, many of his aesthetic and conceptual ideas reached beyond off-the-shelf technology. Haskell Wexler, ASC told Kubrick that Ed DiGiulio, president of Cinema Products Corporation in Los Angeles, was responsive to the demanding requirements of filmmakers, prompting the director to call DiGiulio about his technical needs for Clockwork. After their discussion, DiGiulio purchased a standard Mitchell BNC for Kubrick, which Cinema Products overhauled. DiGiulio also supplied a joystick control for smooth operation of zoom lenses, and a BNC crystal motor. Interestingly, the BNC was not modified for reflex viewing, allowing Kubrick tremendous flexibility in the use of special lenses.

For this film, Kubrick envisioned shots that would utilize extremely long, continuous zooms. “Stanley started chatting with me about getting a 20:1 zoom lens, and I said, ‘We could do it,’” DiGiulio reported. He explained to Kubrick that his company could take an Angenieux 16mm 20:1 zoom and put a 2x extender behind it so that it would cover the 35mm format. However, there would be a loss of two stops of light. “The next day I get a telex that’s a yard long in which he explains to me that the 35mm format he’s shooting in is 1.66:1,” DiGiulio remembered. “Then he recites Pythagorean theorem to show me how X squared plus Y squared equals the diagonal root of the sum of the squares — and to point out that [in] going up from a 16mm format, I didn’t need a 2x extender, that I could do it with a 1.61x. Therefore, I didn’t have to lose two stops — maybe a stop or stop and a half. Here he is lecturing me, and I’m saying, ‘Why this smart ass, another one of these wild-ass directors.’ I called my old buddy Bern Levy, who was working for Angenieux at the time, and I said, ‘Bern, I’ve got this wacko director who wants to do this.’ Bern said, ‘Well, you know, Ed, as a matter of fact we do have a 1.6x extender.’ And I said, ‘Oh, shit.’ This extender existed for some other application, but the bottom line is that I was able to take a 16mm zoom lens, put this extender on it, and give Stanley the exact lens he wanted.”

One outstanding use of this lens system is Clockwork’s signature opening shot, which begins as a tight close-up on Alex’s sneering face and then slowly zooms out as the camera dollies back, revealing his trio of thuggish companions and the bizarre interior of their favorite haunt, the Korova Milkbar. “That shot is one of the great opening sequences," actor Malcolm McDowell told Neon magazine. “Of course, it’s because of Stanley’s technical ability. He saw it the next day and came in all excited. He said, ‘You raised your glass, didn’t you? To the audience?’ I said, ‘Yes, to the camera.’ He didn’t notice it during filming. But what an opening.”

Not incidentally, Kubrick chose to shoot Clockwork with a 1.66:1 aspect ratio partially due to his disgust over the treatment that 2001 suffered in theaters. Improper projection had often all but ruined his precise Super Panavision 70 compositions, compelling him to finally switch to a relatively fail-safe, near-Academy frame. None of the filmmaker’s subsequent films were wider than 1.85:1.

A Clockwork Orange was shot on location for $2 million during the winter of 1970-’71. Kubrick’s home, then outside London in Abbot’s Mead, was the command center for the production. The property included editing rooms and a music facility which had a carefully catalogued record collection. The director had screening facilities in his living room, and a garage that served as his office. “Kubrick said, ‘I want to make the movie within an hour and a half’s travel time of my house, so figure out how far I can reach in that time in the rush hour,’” line producer Bernie Williams told Neon magazine. “We sent an army of production assistants to go out and shoot stills and do homework on locations. We bought 20 VW minivans, and made them into mobile offices and prop trucks so we could get around more quickly.”

Kubrick wanted to create his near-future world by utilizing the modern architecture of contemporary England. He and production designer John Barry spent weeks going through architectural magazines in search of suitable shooting sites, storing selected pictures in a German-made Definitiv display file, which allowed them to cross-reference the material in limitless ways.

The neighborhood block that was home to Alex’s flat was shot in Thamesmead at Wandsworth, an architecturally bold project in London. The auditorium used to display Alex’s cure during a press conference was a library in South Norwood. The writer’s house was shot at two separate locations: the exterior was a house at Oxfordshire, and the interior a home in Radlett. The recently built Brunel (later West London) University was used for the Ludovico medical facility. The deserted theater where a woman is raped and Alex and his “droogs” battle another gang was filmed on the derelict stage of the old casino at Tagg’s Island.

New lens technology made it easier to shoot on location while maintaining Kubrick’s strict technical standards. The record boutique sequence, filmed at the American Drug Store in King’s Road, Chelsea, was shot with an Angenieux 9.8mm lens, which allowed a 90-degree viewing angle. The f.95 lens made it possible to shoot in a room with natural light until late in the afternoon with 200 percent less light than the earlier standard f2.0 lenses required.

The only sets built for the film were the aforementioned Korova Milkbar, the prison admission area, and the writer’s home’s bathroom and entrance hall (other interiors there were shot at a futuristic property known as Skybreak in Warren Radlett, Hertfordshire). These sets were created in a warehouse just minutes from Borehamwood, and were designed solely because they couldn’t be found on location.

To create the Korova’s ambience of sublime debauchery, Kubrick hired sculptor Liz Moore (who had built the Star Child for 2001) to create a series of tables and milk dispensers in the form of provocatively posed nude women. Kubrick’s plan was inspired by a gallery exhibition he’d attended which had featured furniture composed of life-sized fiberglass female figures. (To aid Moore, he directed John Barry to photograph a nude model in every position he thought might make for a suitable table.) “There are fewer positions than you might think,” Kubrick commented with his typically dry wit.

Other, equally suggestive paintings and sculptures were gathered from various artists to help set the tone for Alex’s world of sex and violence (some of these are prominently displayed in his bedroom and at the “health farm” where he commits his murder). To add some contrast in the writer’s home, Kubrick selected “Seedboxes,” a sunny picture painted by his wife, Christiane, depicting flowers drenched in ochre light.

Since Kubrick’s early days as a still photographer, he had centered his compositions. Centered and counterbalanced images are pleasing to the eye and respect the frame that embraces them. A centered image represents order, control, discipline, logic and organization — the very qualities inherent in Kubrick’s personality. Shot by shot, Clockwork generally maintains these austere principles, yet the filmmaker recognized that telling Alex’s tale also required the use of more avant-garde camera techniques. “Telling a story realistically is such a slowpoke and ponderous way to proceed, and it doesn’t fulfill the psychic needs that people have,” the director told Paul D. Zimmerman of Newsweek. “We sense that there’s more to life and to the universe than realism can possibly deal with.”

Kubrick told Joseph Gelmis of Newsday, “I wanted to find a way to stylize all of this violence, and also to make it as balletic as possible.” Toward this end, the director over- and undercranked the camera to cinematically interpret the film’s graphic images of brutality, transforming the acts into something beyond mere explicitness. “The attempted rape on stage has the overtones of a ballet,” Kubrick commented. “The speeded-up orgy sequence is a joke. That scene took about 28 minutes to shoot at two frames a second. It lasts on screen about 40 seconds. Alex’s fight with his droogs would have lasted about 14 seconds if it wasn’t in slow motion. I wanted to slow it to a lovely floating movement.”

Perhaps the most subtle yet extreme cinematic departure from reality in Clockwork is the scene in which Alex and his cohorts take a midnight joyride along a country lane in a stolen “Durango 95” sports car, playing “hogs of the road” with other travelers of the night. The master shot is a head-on angle of the car, with the three passengers hanging on tight as Alex tests his nerve at the wheel. The sequence was photographed on a process stage, with the passing scenery in the nighttime background plate glowing in ghostly fashion. The high-contrast rear-projection footage is overly bright and nearly monochromatic, recalling a similar effect created for F.W. Murnau’s Nosferatu in scenes featuring the vampire’s black carriage eerily racing through the night. Intercut shots representing Alex’s POV of the road were slightly undercranked and ostensibly lit by the car’s headlights. A master at the use of projection effects, Kubrick probably employed the exaggerated background plate to convey the euphoria of his drug-addled characters.

To depict Alex’s perverse fantasies, Kubrick turned to movie history in order to illustrate the character’s dream state as he listens to his beloved Beethoven — perhaps suggesting that Alex’s stunted imagination is only capable of regurgitating prefabricated images. Some of the “dream” shots were composed of stock footage, while the filmmaker also relied on re-creations of moments from other motion pictures. “The book describes things stylistically that I couldn’t film,” Kubrick told Joseph Gelmis.

“I just wanted to have him visualizing some very inappropriate images one might think of while listening to Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. Violent images. The cavemen sequence came from One Million Years B.C., the film with Raquel Welch. [Alex] would imagine things he had seen in films.” A low-angle shot of a woman in a white dress falling through the trap door of a hangman’s platform — displaying both her undergarments and the sudden jerk of the noose snapping her neck — was based on a shot seen in the black-comedy Western Cat Ballou, which Kubrick elaborately restaged. The image lasts less than one second, yet adroitly epitomizes Alex’s crude sexual aggression toward women.

Partially for the sake of production speed and economy, Kubrick and Alcott primarily relied on practical lamps to light the film. Both the Korova Milkbar and the health farm feature clusters of bare Photoflood bulbs built into futuristic fixtures, while other scenes — such as those set in the prison — feature single bulbs strung simply from the ceiling, or exposed fluorescent tubes glowing brightly. Color temperatures often clash.

To supplement this illumination, Alcott often used very lightweight Lowel 1,000-watt quartz lights bounced off the ceiling or reflective umbrellas. This approach allowed Kubrick to shoot 360-degree pans without concern for hiding cumbersome studio lamps, though larger sources were required for many scenes, such as when Alex and his gang assault an old drunk in a harshly lit underground alley. “I find that the Lowel light has a far greater range of illumination from flood to spot than any other light I know of,” Alcott would later note. “In fact, it’s the only light of its kind that gives you a fantastic spot, if you need it, and an absolute overall flood. Also, when you put a flag over most quartz lights you get a double shadow — but not with the Lowels. But then, of course, they were designed by a cameraman.”

The Clockwork production was originally slated to shoot for 10 weeks, but ultimately took close to a year. Kubrick’s usual high shooting ratio and meticulous methods contributed to the lengthy production schedule. The director demanded 30 takes for the shot in which Alex unexpectedly whacks Dim (Warren Clarke) with a heavy walking stick while they lounge at the Korova. During the shooting of the scene in which Alex bludgeons the Cat Lady (Miriam Karlin) to death with a large penis sculpture, the technical crew was crouched down outside the room while the director personally filmed McDowell and Karlin with his handheld Arri 2C. Writer Alexander Walker was an observer and participant in the event. “Kubrick had decided to shoot the fight to the death in 360 degrees with a handheld camera; the Steadicam hadn’t been invented at that point,” Walker told Neon magazine. “Kubrick held onto the camera, the man with the power-pack held onto Kubrick [from behind], and I held onto the man with the power-pack. We were whirling around and it was very difficult to control [our] momentum; we’d end up in a heap on the floor, or I’d be swung around and end up in shot.”

Seven months into production, Kubrick began to reshoot or match shots that had been completed earlier. “Once I had to match a laugh [I’d done] eight months before, and I couldn’t do it,” actor Warren Clarke told Neon magazine. “I was standing on a rostrum and the camera was below, looking up, so Stanley was tickling my legs, giving me whiskey, a funny cigarette to smoke He tried everything, and I just couldn’t match it. I thought I’d really let the man down and felt despondent, but he was really cool about it — which was unusual, because generally if someone didn’t do something right, he’d fire them.”

Perhaps the most audacious scene in Clockwork is the ruthless attack on the writer (Patrick Magee) and the rape of his wife (Adrienne Corri) by Alex and his gang. Little was accomplished during the first two days of shooting, but on the third day, Kubrick blocked out a portion of the action with McDowell, instructing him to knock Magee to the floor and begin kicking his guts out. The director then suddenly asked McDowell, “Can you sing?” It was suggested that the actor could improvise a song-and-dance number while administering the savage beating. McDowell confessed that “Singin’ in the Rain” was the only tune he knew by heart. This resulted in what Kubrick calls the CRM, or “critical rehearsal moment,” during which the director and actors come together to create a defining scene.

Kubrick immediately looked into obtaining the rights to the song, and discovered that the fee was $10,000 to use it for 30 seconds. Once the rights were in hand, shooting proceeded immediately. Kubrick later invited Stanley Donen, the director of the musical classic, to view his scene and then asked Donen’s personal permission to use the song for the sequence. “He wanted to make sure I wasn’t offended,” Donen reports in the biography Dancing on the Ceiling. “Why would I be? It didn’t affect the movie Singin’ in the Rain.” Gene Kelly, who had performed the famous number in the 1952 film, felt otherwise. When Kelly and Kubrick met at an awards ceremony following Clockwork’s release, the danceman refused to talk to the director.

Kubrick cut A Clockwork Orange at his estate with editor Bill Butler. They worked with two Steenbecks so the director could continuously screen film for selection. He relied on a Moviola for the actual cutting. At first they put in 10 hours a day, seven days a week; then, as deadlines approached, they expanded to 14 to 16 hours a day.

Music was a crucial element at the center of Burgess’s story, exemplified by Alex’s supreme love for the works of Beethoven. Kubrick wanted classical music throughout the film to provide point and counterpoint with the story. In order to bring a futuristic quality to 18th-century motifs, Kubrick looked to electronics. After hearing Switched-on Bach, a record of synthesizer performances, released in 1968, Kubrick hired Walter (later known as “Wendy”) Carlos to compose and realize the Clockwork score, which included pieces by Purcell, Rossini, Elgar and Beethoven. The music was recorded in stereo, but Kubrick disliked stereo recording for film; the soundtrack was therefore re-recorded in mono. A Clockwork Orange became the first feature to use Dolby noise reduction on all aspects of the mixing process.

After showing the first print of the titles at the National Screenings Laboratory, Kubrick criticized a hairline shadow on one of the backgrounds and gave a list of instructions. A week before the premiere, the master negative was scratched and the color quality was not to Kubrick’s specification, so he decided to switch labs. The filmmaker personally drove the 16 reels of cut O-negative to the new facility in his tank-like Land Rover, and had editor Bill Butler drive a separate car a short distance ahead of his vehicle in order to absorb any impact in the event of a possible traffic accident.

After review by the Motion Picture Association of America, A Clockwork Orange received the dreaded “X” rating. Dr. Aaron Stern of the MPAA was especially concerned with passing the high-speed menage-a-trois scene, arguing, “If we did that, any hardcore pornographer could speed up his scenes and legitimately ask for an R on the same basis.” The picture was released in the U.S. in December of 1971 to strong critical and public response. However, in October of 1972, Kubrick, who had final-cut approval, withdrew the picture from theaters for 60 days to replace 30 seconds of explicit sexual material from two scenes with less-objectionable alternate footage. The MPAA gave the new version of the film an R rating and the picture was re-released at the end of the year.

A Clockwork Orange was nominated for Best Picture by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, while Kubrick was nominated for Best Director and Best Adapted Screenplay. Bill Butler was nominated for his editing. While it did not earn any Oscars, the film did receive the New York Film Critics’ prize for Best Film of the Year, with Kubrick winning for Best Director.

In 1974, after several copycat crimes were attributed to A Clockwork Orange, Kubrick pulled his film from distribution in England, making it illegal to show it anywhere in the country. The ban was not lifted until the filmmaker’s death on 1999.

Tragically, John Alcott died of heart failure at the age of 55 in August of 1986 while vacationing with his family in the south of France. Although Kubrick continued to control every aspect of the cinematography on his films, Alcott made an enduring and distinctive contribution to A Clockwork Orange, as well as Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon (for which he earned an Academy Award for Best Cinematography — see AC Mar. ’76), and The Shining (AC Aug. ’80). The use of light in these films is intrinsically linked to Alcott, marking just one of the many contributions he brought to his work with Kubrick. The cinematographer’s later films included Fort Apache the Bronx, Under Fire, Greystoke: The Legend of Tarzan, Lord of the Apes and No Way Out.

Despite his brief career, Alcott left us the legacy of a constant search for technical and aesthetic excellence, a keen parallel to Kubrick’s own pursuit of these virtues.

Vincent LoBrutto is the author of Stanley Kubrick: A Biography. Additional material was provided for this article by David E. Williams.

A Clockwork Orange was selected as one of the ASC 100 Milestone Films in Cinematography of the 20th Century.

This video essay goes into detail on the film's cinematography, illustrating many of the points made in this article:

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.