Blood Road: Emotional Journey

Director Nicholas Schrunk and crew document an endurance mountain biker’s trek across the Ho Chi Minh Trail to learn about the father she never knew.

Director Nicholas Schrunk and crew document an endurance mountain biker’s trek across the Ho Chi Minh Trail to learn about the father she never knew.

Rebecca Rusch was 3 years old when her father, U.S. Air Force pilot Stephen A. Rusch, was shot down over Laos in 1972. She grew up to become one of the world’s greatest female ultra-endurance mountain bikers — and a woman whose unwavering curiosity about her father led her to trek 1,200 miles of the Ho Chi Minh Trail. Director Nicholas Schrunk and his intrepid crew documented Rusch and cycling partner Huyen Nguyen’s journey through Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia for the feature Blood Road.

Schrunk and director of photography Ryan Young shot the Red Bull Media House production primarily on Red Epic Dragons in 6K, with additional footage captured on drone and GoPros. All cameras were fitted with anamorphic lenses, which yielded a widescreen picture that offers both an intimate look at the subjects and a broad view of stunning landscapes and treacherous terrain. The following interview is based on AC’s Q&A with Schrunk at last year’s Cine Gear Expo, with additional information provided by the director in subsequent communications.

American Cinematographer: Tell us a bit about the background of Blood Road.

Nicholas Schrunk: This film, for me, started three years ago. It was when ultra-endurance

mountain-biking world champion Rebecca Rusch came to us with an idea. She wanted

to ride her mountain bike the entire 1,200 miles of the Ho Chi Minh trail through

the dense jungles and rugged mountains of Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia — to find the

crash site where her father, a fighter pilot in the Vietnam War, was shot down some

40 years earlier, and of whom she has no memories because she was only 3 years old

at the time. When she came to us with that idea — that was really, really special.

We thought, ‘This is a genuine story with some real depth,’ and the last three years

have been a result of that one day when we met, and she told us her initial story.

It’s not just an expedition-adventure movie; it’s really an emotional journey.

What kind of prep work goes into shooting a bicycle trip on

the Ho Chi Minh Trail, in terms of locations, story and techniques?

Schrunk: At the beginning of

any film project your mind races through all the joy, wonder and expectations of

what could be. And then, very shortly, reality set in: These are three vast and

uncharted countries. Where are we going? Why are we going there? What are we going

to encounter? Will people welcome us? Will they be repulsed by us? How are we

going to survive, let alone make a film? What are we going to find? We had to satisfy

these questions — before you can even turn a camera on. We started to build our

team, and look at the limitations based on what we can pull off, in terms of budget,

time and location, and then we execute.

It all really starts with the location — and I immediately felt

this anxiety, thinking, ‘We just have to get over there.’ Researching online is

a first step, of course, and we can do lots of research — you can look at Wikipedia

all day — but until you actually get there, that first day you set foot in a country

is when you really need to figure everything out. So for this project, one of the

amazing things was that our producers saw that the strategy lay in preproduction

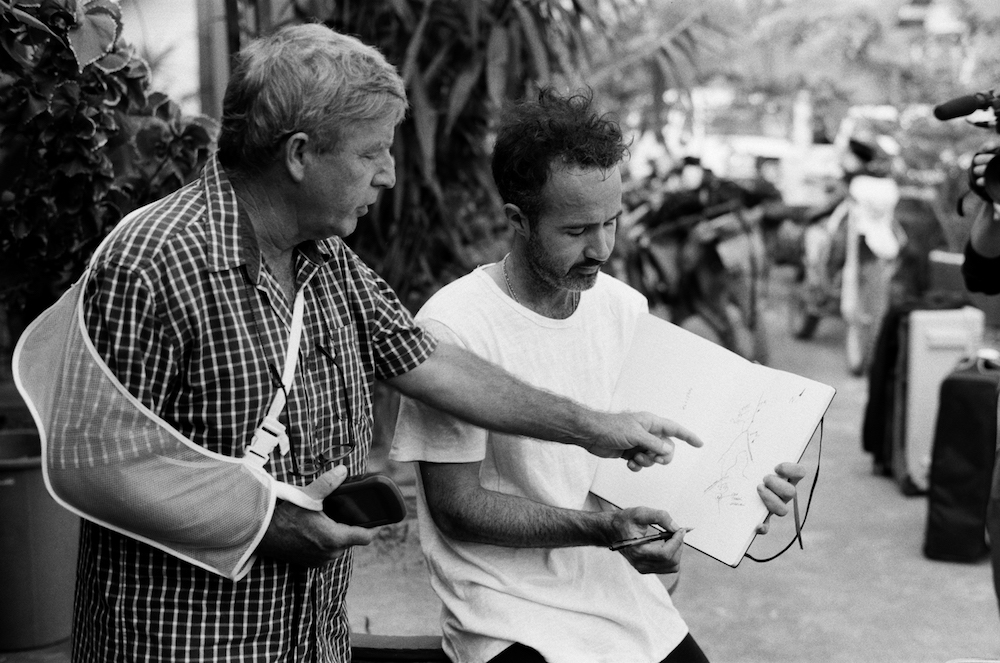

and scouting. The initial location scout was actually three months long, of myself

and Don Duvall — the local guide who mapped the entire Ho Chi Minh Trail — putting

together the giant logistical flowchart that afforded us the planning knowledge

to even get cameras turned on.

You covered a huge amount of ground, traveling 1,200 miles on a month-long shoot. How did you go about scouting, and what were some of the methods that made the endeavor possible?

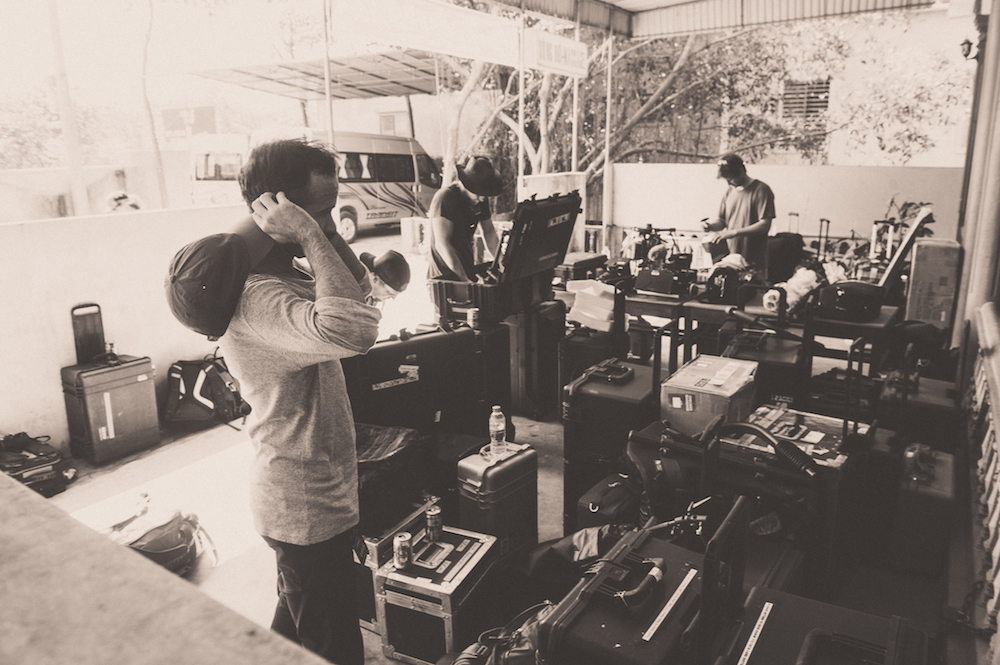

Schrunk: There are a few things that became really important once we got there. There’s really only one way to traverse these countries, and that’s on dirt bikes — or dual-sport motorcycles is the more proper term. [We used] Honda CRF 250cc Enduro motorcycles. Sure, you could take trucks on some of the dirt roads, but dirt turns to mud in an instant and you’re going to be stuck. So the first thing was figuring out how to put production together when the only equipment we could carry literally had to go on our backs for the entire production.

Location-scouting three countries is kind of a funny thing to describe. You may not know, as I didn’t at the beginning of the project, that the Ho Chi Minh Trail primarily routes through the countries of Laos and Cambodia, and not Vietnam. It was a supply route for the North Vietnamese to supply the insurgents in the south, so the route goes through the densest jungles and the rugged mountains of the three countries, because it was purposefully secretive. And when it was bombed from the air, which was the Americans’ method of stopping the flow of supplies, it would be rerouted. It’s a braided network that isn’t something you just plug into Google Maps. If you can imagine just kind of zigzagging back and forth on these lines, trying to find not only how to get around, but also, ‘What’s our story? What might she find? What would we hope for her to find?’

The one thing I knew was that we couldn’t afford to have the entire crew over there for months with me. We had limitations in terms of people’s time and, of course, a documentary budget. One important tool we used to take that 1,200 miles was a handheld GPS. I engraved a 2.40 guide into the lens of the handheld Garmin unit so that I would take location photos that were tagged with GPS information that easily could be put into mapping software. Then, when the actual shoot happened, we had an extensive shot list of where the story-building and visual shots would happen — so that if I got separated from our crew, our camera department always knew where and what to do, even if I couldn’t be with them directly.

How many people were on your crew? Was the entire crew on dirt bikes, carrying their own equipment?

Schrunk: We had help from the local Laotians, Vietnamese and Cambodians, but it was a core group of six filmmakers. It was myself, director of photography Ryan Young, drone operator and field audio Neil Goss, camera operator Sean Aaron, Movi operator Robert J.D. Spaulding, and drone pilot Nick Wolcott. They were all outfitted on dirt bikes, in full motorcycle gear — helmet, armor, high boots — looking like Stormtroopers in camouflage on their overloaded dirt bikes.

Did you have periodic support for the crew?

Schrunk: In preproduction, when we were putting this production together, we [planned out] predetermined meet-up points, where our team would offload media, charge batteries, fuel up, get food and water, and take a quick breather — those things are just as important as actually getting footage. There are some days where we saw support every day. There were a couple of times where we didn’t see them for multiple days, in which case we just had to be very careful in terms of how much media and battery we were using, etc.

What kinds of challenges did you face in traversing and documenting your 7-mile trek through the cave in Laos?

Schrunk: The biggest challenge was that all of your internal senses are kind of saying, ‘Do not do this. Don’t go into this dark cave, where you don’t know the way out, and you’re likely going to get out in the middle of the night. Just don’t do that.’ Once you get over the borderline absurdity of what we’re doing, it was an outright challenging scene to shoot. The storyline was ‘Can’t go around it, can’t go over it, got to go through it.’ So, we’re going through it with Rebecca and her Vietnamese teammate, Huyen Nguyen, and we have to have camera rolling. We had to engineer a few solutions to make this scene work in complete darkness.

You have to get audio — our heroes were not happy to be in there, and you don’t want to miss that conflict. Lighting was the challenge, and we actually used Light & Motion Stella waterproof lights for the entire shoot, specifically because we could only bring limited equipment, and we needed [the rigs] to be totally waterproof. We adhered one directly underneath the raft, so there would be a little bit of light separation underneath it, which would at least separate it from the total pitch-darkness, as they traversed the cave. We also gave them these headlamps meant for nighttime bike racing to help paint any exposure around them. We ran the low-light OLPF on the Red Dragon for these scenes, and boosted the ISO to around 1,600 to 3,200.

The drone lights, which again were Light & Motion, were adhered [to the underside of the drones], and we would fly those over the top of the scene [to provide backlight] for more of a moonlight effect, just to get a read on how big this cave was — but, of course, you’re ruining the audio with a high-pitched drone while you’re doing that. It was actually something fun for our crew and talent to get to do [when we shot with drones]; it would actually clear away all the bugs, snakes and other creatures — as opposed to when we’d take the drone down and start shooting handheld. So between those two methodologies, we made it through.

You would think it’s all water in the cave, but I would say one-third of it is sharp, pointy, slippery rocks honed by thousands of years of erosion. They were all exposed because it was the dry season. So imagine walking over slippery, pointy rocks while hearing, ‘Hey, we’ve got to get this! This is great, guys! This is amazing!’ yelled in your ear. And then your other ear is your talent screaming how pissed they are. I want to give the camera team credit — I don’t think we could have engineered a more difficult environment to shoot.

Your main camera techniques were tripod, handheld, Movi, drone

and jib — is that right?

Schrunk: That’s correct. You’ve

got to be able to carry [the gear] on your back, or you might only get to use it

a few times. The story that we’re telling is an emotional journey, but we still

have to capture a level of visual polish of our location. We’re going to a beautiful

place, and a main character is actually the three countries. So yes, we had to break

it down into these five different techniques.

What can you tell us about your use of drones on Blood Road?

Schrunk: Principal photography

was early 2015, and while there were several great solutions for drones and gimbals,

it certainly was a challenging time to get above the micro-sized sensors and fisheye

look while keeping compact and reliable. Our primary drone was carrying a Movi M15

gimbal and a Red with anamorphic lenses. Our secondary was the DJI Phantom drone,

which had just come out, and they were carrying GoPros. The GoPro look is too wide

and it doesn’t really give much control of our shot — so we said, ‘Here’s something

that can travel in a backpack and that captures beautiful environments, so we have

to figure out how to make them good enough [for our needs].” So we actually modified

them. We ripped out the lenses and put in tighter ones. We used Peau Productions

to modify the lenses, and settled on 4.35mm (72 degrees

FOV) and 5.4mm (about 60 degrees FOV). From there, we added an anamorphic front

element to squeeze the image — and then [added] custom filter trays from Snake River

Prototyping to match and cover the anamorphic element with ND and grad filters.

They looked like a Frankenstein camera, and the drones and gimbals actually had

to work pretty hard to get them up in the sky. Drones, in the last few years, have

been one of the most amazing camera-movement tools to become accessible for productions.

The fact that drones became “reliable enough” right when we

started production allowed us to have these slow, creeping motions calling attention

to certain elements of the landscapes — and rotations, and very complex camera moves

that can be done by one or two people very easily. The drone work in this production

tells the story of the landscapes. It also tells a lot of the story of the destruction

that still exists in these countries, 40-plus years later. When I was first told

by the villagers that this giant hole in the ground was a bomb crater from a bomb

that the Americans dropped 40-plus years ago, my emotional response was muted, to

be honest, because you’re just trying to imagine it. From the ground, it looks like

a pond, a hole in the ground — but when viewed from the air, and you’re able to

see the scope of the destruction, that’s a really strong technique, and it’s one

that I feel adds so much to what we were able to accomplish with our story.

This is a good example of how all manner of landscapes can be

photographed that haven’t been before, because filmmakers now have the ability to

do it on relatively low budgets.

Schrunk: Exactly. I saw a Facebook

video recently, of a guy who ran up Everest in 26 hours, and there’s a drone shot

of him nearing the peak. This is an amazing filmmaking tool. So many [aerial shots]

have been just outside of a lot of production budgets, because they required a helicopter

and very expensive gimbal, and now documentary and travel productions [can afford

to shoot them]. Drones travel in a backpack and they really don’t add that much

weight and size to the gear package.

Can you explain the circumstances that led to the drone crash-landing

in

Southern Laos?

Schrunk: While we had a few DJI Phantoms on the shoot, our main drone

was a larger unit carrying a Movi M15 with a Red Dragon outfitted with either a

40mm or 50mm Kowa anamorphic lens. At this

point in most of our filmmaking careers, we’d either experienced a drone crashing

first or second hand. We had had an extremely successful shoot, and the drone pilot,

Nick Wolcott, was one of the best drone pilots we had, and the gear was great —

but for whatever reason, the drone lost control and crashed in the middle of the

jungle. What happened, we found out later, is that there really are no public RF

channels over there. It’s all government owned. Unlike the U.S., when they’re using

it, they’re using it — so the drone going down [was due to the radio signal being]

scrambled, and the drone just started drifting away. And you’re just like, ‘Maybe

the spirits really don’t want us here right now.’ That being said, it was quite

amazing how we recovered it. It actually fell into a crater field where there were

still live ordinance — bombs — left from the war. We had to have the locals bring

us out on specific footpaths that they knew had been cleared by the clearance teams.

When it actually came back, I was thinking that we were going to be shooting this

whole thing on a single camera body for the rest of the shoot, and we’re definitely

not going to have Movi working. But actually, that Red — with almost no maintenance

— came back to life. The camera was actually still rolling when we picked it up;

we put a new lens on it and we shot with it for the rest of the trip.

Did you need permits to fly the drones?

Schrunk: No, not at all. In

fact, everywhere we went, people couldn’t wait for us to get the drones out. In

Ho Chi Minh City — [formerly] Saigon — in Vietnam, there were no permits necessary

to fly over the city or over the water. The only thing that got dicey — and of course

there’s no one to tell you this until you’re doing it — is flying them close to

any type of military installation, in which case you very quickly find out it’s

not okay. It’s very liberal over there. They don’t mind, but there are also no guarantees.

There is RF interference from everything fighting with drone/gimbal control and

wireless video. You fly your drone at your own risk.

How did you capture the low angles of the bicycles when Rebecca

and Huyen are riding through the streets?

Schrunk: In early 2015, Freefly

had just come out with the [Movi] M15 gimbal, which was able to carry the heavier

camera packages. The Red isn’t very heavy, but once you outfit them with anamorphic

glass, wireless video and focus, they start to max out. This was a game-changing

tool for us. Many shots [in the movie] that I’m really proud of were Movi gimbal

work. [We mounted] the Movi to motorcycles, and to the front of cars to make our

own camera car.’ [We used to make those mounts] out of aluminum and mountain-bike

shocks. This was well before the days of the Black Arms and other engineered

solutions, and we really were figuring these out

from scratch, with help from Freefly.

The shots that really resonated with me were when I was standing

next to Movi operator Robert Spaulding, looking over his shoulder as he was shooting

out the back of a pickup — or [when he was] hanging off the back of a motorcycle.

He was getting worked really hard, but it was just amazing that these very complex

moving shots were able to isolate little parts of their journey. For the shot [of

the bicycles] that takes place right after the climax of the film — in the narrative,

[Rebecca] has just gotten the satisfaction of [achieving] her purpose of the trip,

and is riding away, and we’re shooting Movi from a truck bed to the two heroes on

their bikes. I just love that simple shot, because it functions so well for the

story. It’s got all the things we cinematographers want, which is movement, subject

separation, anamorphic isolation, eyes — we’re really proud of that. (My

background is in cinematography, having started as a camera operator, primarily

using the Vision Research Phantom cameras.) Prior, we’d

be shooting over-cranked to try to create these moments of reflection in the story;

now we’re able to do this on the gimbals with much more control.

What techniques were you using for the sequence in which you’re

tracking around Rebecca and Huyen in the Cambodian Buddhist temple?

Schrunk: That was actually hand-carried

Movi. In the gimbal world, this [skill] is very sought-after — this way of walking

that puts no bobble into the shot. That scene in particular [represented] Rebecca’s

realization, after the climax of the film. It was totally unplanned. We stopped

for lunch, walked into this temple, and had this amazing story point happening.

We have no follow-focus — we just have a camera with a 40mm lens, and Robert to

carry it, and it was amazing — just the simplest move. The tilting around offered

such an emotional response. It’s amazing how sometimes the simpler camera moves

are really the way to execute those types of story points.

In the sequence where the elephants are walking by, it looks

like the crew is practically underneath them.

Schrunk: We were. That was the

morning we woke up and I heard the drone flying. It’s about 4:30 in the morning

and one of our crewmembers couldn’t sleep and thought it’d be fun to fly the drone

around and see what we could find. We found a whole bunch of elephants coming into

town and we said, ‘Okay, we’ve got to go and shoot this. These are the fabled wild

elephants. Elephants don’t exactly love a bunch of guys dressed in Stormtrooper

gear with a bunch of bright, shiny metal things running at them, so there was actually

an acclimation process of saying ‘hi’ to the elephants, and letting them know why

we’re there. The elephants ultimately didn’t mind us. That was a shot where we used

dual operators, pulling focus and operating gimbal.

What techniques were used when you rode along with Rebecca and

Huyen on the jungle trails?

Schrunk: That was some of the

most challenging shooting, because you have these world-class endurance athletes

that will just go, and go, and go — and even though it’s a very difficult journey

for them, in capable hands a mountain bike is an efficient way through the jungle

trails. A dirt bike’s not a bad way, either, but you have to stop, get your stuff

out of your pack, boot your camera and compose your frame. Even with the camera

team of damn-near professional dirt-bike riders and sharp, prepared cinematographers

planning for it, that’s going to be 10 minutes from stop until you’re ready to roll.

Then you get back on the bike, and she’s already 2 kilometers up the road, and speeding

along. We had to be quick to react.

Though we did occasionally use the GoPro cameras to capture

some in-the-moment footage — mostly used for ‘filler’ — handheld shooting and tripods

[using the Red cameras] were really big parts of this. In my opinion, when you’re

shooting with a tripod, you’re really isolating your frame. You’re saying, ‘This

is my frame and my story’s going to happen here.’ Often, even in the moments where

we had all the filmmaking tools with us, we would still choose to shoot wide on

a tripod because it was such a gorgeous environment. Just having them ride through

it was so simple and elegant, and really told the story of the land more than adding

camera motion or other things that are beautiful in their own right — but sometimes

you don’t need them. And, quite commonly, we just didn’t have access to them.

Tell us about your collaboration with director of photography

Ryan Young.

Schrunk: Ryan Young and I have

known each other for almost 10 years. He’s traveled the world specializing in action

and adventure filmmaking working with top athletes. He’s an amazing cinematographer

who could really [understand] our athletes’ challenges.

Neil Goss and Sean Aaron, two of the other operators, were athletes themselves,

and they were chosen for the same reasons — they could really understand the way

an athlete’s mind worked.

So while Ryan was making amazing shots happen with very limited

resources, he built a rapport with Rebecca and Huyen — as our whole crew did — and

the technology and execution of the tech just kind of fell away. He was able to

get into this ‘flow state,’ as did all of us, [where he felt] what she was experiencing.

It’s this really unique thing that can happen when making a documentary. As soon

as you can forget the technology and it’s just you documenting, and you get that

personal connection — Ryan was able to do that very quickly without compromising

the quality of the shooting, while running the camera department with basically

no resources at all. My collaboration with him was so great, because he could bounce

ideas off of me and I would do the same with him — and without even thinking about

it, we became two people with a single goal. We could be in different locations

accomplishing the same thing, and that’s why he was such a great collaborator on

this project.

Why did you choose to shoot such a physically challenging documentary

with anamorphic lenses?

Schrunk: I’m really proud of

the fact that we were able to shoot this documentary in anamorphic. When we were

doing the initial tests and looking at our story and our scout photos, it was the

big, wide, extensive shots that I thought were the unique things we were going to

document — and couple that with what was going to be a very emotional journey for

Rebecca, and anamorphic offers this amazing ability to pull your characters forward.

We tested all kinds of lenses. The obvious choice would have

been the lightest-weight lens possible, because of the physical journey, but we

just kept coming back to the anamorphic look. Tim Jensen over at Camtec and

Les Zellan at Cooke provided a lot of lenses

for us to try out, and it was really the Cooke Anamorphic/i

lenses that invoked that very warm, inviting feeling in our camera tests. It’s hard

to explain, but the aesthetic of it just pulls you forward, and removes this clinical

edge that digital can sometimes add. It really warmed the scenes, and I felt close

to our characters [in the footage the lenses provided] — and once we got that look,

it was like, ‘We’re going to figure out how to shoot this anamorphic.’ The Cookes

were our main lenses, and we supplemented them with a lighter-weight vintage Kowa

anamorphic set for the gimbal work.

How was your experience mixing these quite old Kowa lenses with

the modern Cookes?

Schrunk: The Cookes offered

a few things. They’re front-anamorphic lenses, so you get a lot more of the optical

abnormalities, and that’s what our director of photography and I were reacting to

when testing. The Cookes also had the benefit of being modern, well-built lenses.

We were lucky enough to get one of the first production sets from Cooke right before

our shoot. They were tough enough to take the temperature changes and the humidity.

While shooting with vintage lenses is very popular as well, and I love the beautiful

distortion and optical elements they provide, sometimes I feel like it’s a little

bit distracting, the same as when you have lens flares in every shot. We had this

running joke that if you opened the aperture wide open and put the sun behind the

subject, I’d love the shot. While that’s true, the Cookes also flared nicely without

making the whole frame bloom.

[The Cooke lenses] gave that end-of-the-day look, with all the

funkiness that you like without blasting a flare across the shot. They also offer

the best combination of warm, inviting skin tones, bokeh in the backgrounds, and

hints of anamorphic funkiness, but they were also technically sharp and tough enough

to stay calibrated and weather-resistant even in full downpour and on the backs

of motorcycles. We enlisted the Cookes for all of the work with dialogue and with

story — with the handheld and tripod work. We then used the Kowas with the gimbals,

because the gimbals worked a lot better with the lighter-weight lenses. You hear

[that mixing modern and vintage lenses is] kind of like two different languages,

but we matched them by running 1/8 Hollywood Black Magic diffusion filters

in front of the Cooke lenses. We took the contrast down

a little bit, so when we got into color and conform, [the images from the different

lenses] were much closer.

In 2015, there really were no feasible anamorphic zoom options

available, because any we might have used would have caused our camera department

to quit because they would break their backs. They’re very large lenses, which are

great for some applications, but not for documentaries — so we shot the entire film

without zooms.

How did you decide on Red cameras for the project?

Schrunk: Because you can crash

them out of the sky and they still work. [Laughs.] In addition to the lens

testing at the beginning, we also did a lot of camera tests. I’m a firm believer

that preparation allows you to experiment and really hone in on your visual language.

So make sure you’re getting what you’re going to want ahead of time, because once

you get in the field, it’s just absurd the things you’re dealing with, and the madness

and speed that you’re going.

We needed a camera that was durable, lightweight, small, and

one that our filmmakers were familiar with. The R3D format is one I’ve been using

for years, so I was really comfortable with that. At the time, [there was the] Red

Epic Mysterium-X 5K, and Red Dragon 6K

that had just come out. We only had prime lenses, and that’s beautiful, but we were

going to miss a lot of moments where we would really want a tighter frame, or you

want to back off a little. We would therefore need to recompose some shots in post,

and we would be able to find our frames much easier using the extra resolution,

mastering 6K down to 4K. So we made some sacrifices to get the 6K version of the

Red cameras.

prime lenses and recompose in post.

We drew an interior box in the viewfinder, [which designated] how much we could push in without [losing] resolution. Then we had the second frame-guide, which of course is the entire frame; that is where you really want to be, because then you get all of the funkiness of the anamorphic edges and the true full S35 frame depth of field. We had this idea that if you can compose through this interior guide, we can push into that and won’t ultimately lose resolution and notice the obvious push-in. If you shoot for the wider box, we can pull back to that, so essentially the camera operators were able to pick their frame with the prime lens out in the field. If we want to switch to the 75mm from the 50mm, we’re going to miss our story. Sometimes you just have to roll.

It took them a few days in post to recompose [the frames] for some of these choices made in the field — but I would rather have a conform artist, our cinematographer and I picking some of the frames where we want a little bit more of a closer emotional view or a wider landscape view, as opposed to missing a story in the field that’s only going to happen once. I’d have loved if the 8K resolution was available then, but 6K offered all of the flexibility we needed to [make those adjustments] in post. That was a major creative decision [during] testing, so that we could get those moments in the best way we can, while using prime lenses in the field.

Because of our limitations with media and the long-take nature

of documentaries, we chose 8:1 Redcode compression as the best compromise of size

and quality. When shooting some specific shots — aerials with foliage, for instance

— we would lower compression to 5:1 to account for the more complex data acquisition

needed. GoPros were run in raw with their native color temperature and ProTune set

to a log color space. We’d generally set exposure bias to -1/2 stop to preserve

highlights, since most of the aerials had plenty of detail in the shadows but would

commonly pop skies above clipping.

Tell us about the color-grading process.

Schrunk: We first started with our visual-effects/finishing

supervisor Jeremy Hunt at Screaming Death Monkey, and he and I set some LUTs ahead of time. With an eventual Dolby Vision grade in the works, we decided to conform in 16-bit

color to really preserve all the color details we could. We took some of the scout footage [to him],

primarily to find out if we could get the GoPro footage even close to the beautiful

Red footage. It’s always a challenge to match

across formats, so what we did was set some layers in smoke to mimic the different

optical characteristics of the Cooke anamorphic lenses, which we could move onto

the GoPro cameras for conform. We also did some proof-of-concept tests based

on the initial scout, and that was really important because you don’t want to have

any jarring visual elements that would take you out of [the viewing experience].

We didn’t bring any LUTs on set, because we

actually didn’t have time for it — we just looked at the histogram and monitored

in a raw color space to keep everything in the ballpark of exposure.

Once the work was complete with visual effects, we brought it

to our colorist Marshall Plante. We did a grade based on the emotional curve of

what we were going through in the storyline. Marshall did a great job of adding

contrast and color at lush, happy moments — and at times of despair, without you

even realizing it, he pulled some life out of shots in ways you couldn’t imagine.

While the photography really dictated the emotion of the piece, the visual identity

was realized in our conform and color correction in the final stages of post.

Rebecca clearly went through some major emotional changes during this experience. What kind of changes did you go through, as a filmmaker and as a person, working on this movie?

Schrunk: Once you get out in the field, you really get your defenses taken down, right? Making a documentary — whether you’re in a jungle, or documenting music, or sports, or whatever — you’re going through a lot. It’s a big chunk of your life. It’s a big investment of your energy, effort and time. The change for me was that I didn’t know how much we would get drawn into the story. We were on the trail doing the same things that she was, more or less, and dealing with the same challenges. [Rebecca has told me that she] doesn’t even remember us being there, and to be honest, I barely even remember any technical decisions we were making at the time. We’re just rolling in this kind of flow state. I didn’t think that would happen. I thought every day was going to be decisions [about] the camera techniques we were using. All of those things existed and were important, but once our approach was decided upon, the emotional connection happened. I’m really proud of the fact that I feel this is a genuine, authentic view of what it was like for her on the trail. I’m so proud that we were able to capture her genuine emotion on this journey.

Blood Road — executive produced by Scott Bradfield, Charlie Rosene and Ben Bryan, and produced by Sandra Kuhn — is available for free streaming here.

Technical Specifications

| Aspect Ratio | 2.39:1 |

| Format | Digital Capture |

| Cameras | Red Epic Dragon |

| GoPro Hero4 | |

| Lenses | Cooke Anamorphic/i |

| Kowa Anamorphic |