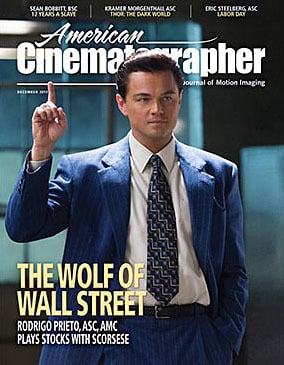

Boom and Bust: The Wolf of Wall Street

Rodrigo Prieto, ASC, AMC and Martin Scorsese discuss their approach to this true story of a stockbrocker runs amok.

Photos by Mary Cybulski, courtesy of Paramount Pictures.

Cinematographer Rodrigo Prieto, ASC, AMC recalls feeling “amazing and excited, but also a bit scared” when he first met with Martin Scorsese to discuss the possibility of shooting The Wolf of Wall Street, which is based on a bestselling book about the rise-and-fall life of famed broker Jordan Belfort (played by Leonardo DiCaprio) during the 1990s. Belfort dived spectacularly into drugs, securities fraud and money laundering, and eventually ended up in jail.

With longtime collaborator Robert Richardson, ASC unavailable, Scorsese turned to Prieto because he had long admired his work, particularly in Brokeback Mountain (AC Jan. ’06) and Lust, Caution (AC Oct. ’07). “In a sense, I would say Rodrigo’s lighting is more naturalistic, and his cinematography more invisible,” the director observes, corresponding with AC via email. “It has an impact on the subconscious [and] creates a kind of energy that nudges the audience in the intended direction.”

Scorsese was pleased with the results he and Richardson had attained with the Arri Alexa on the 3-D feature Hugo (AC Dec. ’11), and he had already decided to shoot Wolf digitally by the time Prieto came aboard. However, rigorous pre-production testing led the filmmakers to choose a hybrid approach. “When we started testing different digital cameras and ideas, I also shot film as a benchmark so I could understand differences in terms of latitude, color and so on,” Prieto recalls. “I shot the same images on film and on digital, and when I screened the tests for Scorsese, he kept pointing to the film versions and saying they looked better, basically noting that the skin tones were richer and there was more color nuance. So, I went to our producers to explore the financial implications of shooting on film negative and reserving digital capture for low-light situations. After looking at the comparative costs, production agreed to work with that hybrid method.”

“We did bear some additional costs carrying additional cameras along the way,” notes producer Emma Tillinger Koskoff, “but at the end of the day, we shot on the media that best served the look.”

Thus, says Scorsese, “we took advantage of both worlds, shooting most of the movie on film, and then using the Alexa for night scenes, experiments with shutter speed, and greenscreen visual effects.” The filmmakers retained the Alexa for the latter because the project had been budgeted based on a digital workflow, and visual-effects supervisor/2nd-unit director Rob Legato, ASC had already designed an Alexa-based methodology for the second-unit work and the creation of more than 400 visual-effects shots.

Legato had collaborated with Richardson on three Scorsese pictures, Hugo, Shutter Island (AC March ’10) and The Aviator (AC Jan. ’05), and says he found it stimulating “to embrace a different approach and learn something new” from Prieto. “After working with Bob Richardson for so long, I had grown to have similar sensibilities about shots and lighting, and Rodrigo has an entirely different lighting style,” he says. “That gave me an opportunity to adapt to a different way of working and seeing things, which I found intriguing. My challenge for both the visual effects and the second-unit work was to match Rodrigo’s lighting style precisely.”

For the production’s film work, which was shot on 4-perf Super 35mm, Prieto chose Arricam Lites and Kodak Vision3 250D 5207 (for day scenes) and 500T 5219 (for tungsten-lit scenes). For the digital work, he chose Arri Alexa Studio and Plus systems, capturing in ArriRaw in Log C wide gamut.

The filmmakers’ global challenge was to figure out how to visually represent the different stages of Belfort’s story. “Rodrigo and I decided to [distinguish] the scenes where Jordan is uncertain or lost from the scenes where he has found some clarity and direction,” says Scorsese.

They decided to achieve this mainly with different optics, lighting styles and color schemes. Using Belfort’s state of mind as his guide, Prieto alternated between spherical Arri Master Primes and anamorphic Hawk V, V-Lite and V-Plus lenses to achieve different degrees of depth, perspective and clarity. Scorsese adds that Prieto also convinced him to enhance the contrast between Belfort’s states of mind by mixing in some diffusion filters, occasionally adding ambient smoke and pushing the negative.

“At the beginning of Belfort’s story, we started with a softer, slightly murky look,” Prieto explains. “He hasn’t found himself yet, and he’s still confused and awestruck by Wall Street. I used the shallow depth-of-field and slight distortion of anamorphic lenses for this first phase of his career.”

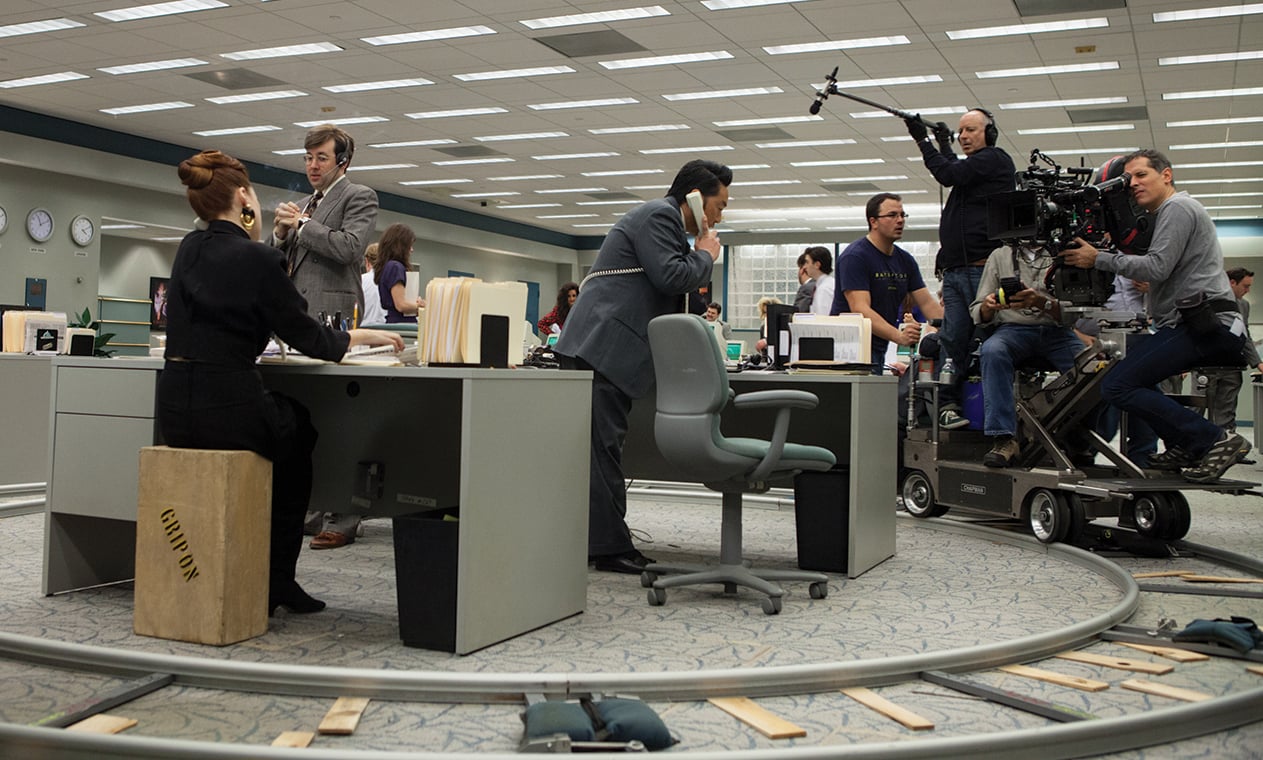

Before Belfort starts his own business, he lands his first job at the firm LF Rothschild, a set dominated by green and gold lighting that evokes “old-world wealth,” as Scorsese notes. Prieto adds, “The color scheme was inspired by a photo I found of a brokerage firm in the 1980s.” Shooting on 5207, the cinematographer used tungsten-balanced fluorescent lights and ¼ Tiffen Black Pro-Mist filters on the Hawk lenses. “For wide shots of the office space, we used the 28mm and 35mm V-Lite lenses, which curved the edges of the frame a bit, adding to the sense of instability,” he says. “This look was not as crisp or clean as the look of Belfort’s later offices, where we used a lot of white. Using daylight stock with tungsten lighting resulted in an amber coloration, and then I pushed those scenes 1 stop to add a little extra grain and contrast. The warm ambient lighting contrasts with the green graphics on all the desktop computer screens and the green LED tickertape in the office.

“When the crash of 1987 happens, LF Rothschild fails and closes, and Belfort finds himself unemployed,” Prieto continues. “He eventually finds work at an investment center as a regular employee, a job he hates. I lit that set only with light through big windows on one side, and the feeling is like a cave, a place where he sort of falls into darkness.”

Eventually, Belfort rebounds, starts his own brokerage house and achieves massive success, only to crash and lose it all. “When he figures out how to make a lot of money and becomes a success, we wanted a crisper, more pristine look — a look of greater clarity,” says Prieto. “We switched to spherical Master Primes and used them without diffusion for this section.

“Then, when he finds himself under investigation and his world unravels, we devised what I call ‘the paranoia look,’” he continues. “We switched back to Hawk anamorphics, this time using longer focal lengths to create a sense of being spied on, and for some scenes we added some ambient smoke so the backgrounds became slightly milky, with shallow depth-of-field. For those scenes, I also pushed the film stock [both 5219 and 5207, depending on the scene] 1 stop to add grain and contrast.”

First AC Zoran Veselic jokingly calls the Hawk lenses “anamorphic Master Primes” because “they have that same quality of crispness and sharpness, but with a slight anamorphic falloff. We loved their consistency. On the longer end of the primes, we started the show with a V-Lite 140mm, and then we decided to continue with a V-Plus 135mm, which we found a little bit sharper.” Prieto also used V-Lite 45mm, 55mm, 65mm, 80mm and 110mm primes; V-Plus 45-90mm and 80-180mm zooms; and a V series 180mm.

Prieto’s approach was adapted more specifically to visually distinguish the three iterations of Belfort’s company, Stratton Oakmont, as it grows. After starting out in a refurbished auto shop, Belfort moves his business into a proper office, and then, finally, into a large, ornate office space. To help differentiate among the settings, Prieto used different color-temperature mixtures and applied various filters and diffusion.

When Belfort starts his own company, the old auto-shop location is “darker and grittier than his evolving office spaces,” says Prieto. “I also pushed the stock, both 5207 and 5219. We lit the space with 2K Fresnels and some Cool White fluorescent practicals. In addition, we rigged [Kino Flo] Image 80s in the ceiling to enhance the fluorescent fill, using 2,900°K tubes for night and 5,500°K tubes for day scenes.”

After that comes Belfort’s “power look,” as his offices grow more opulent. Scorsese describes this as “a crisper, cleaner look, with wide focal lengths, deep focus, white light, vibrant contrast and quick, defined camera moves.”

The final iteration of Belfort’s company, Stratton Oakmont III, is an enormous space with windows on three sides and glass-walled offices. This practical location was the third floor of an office building in Westchester, N.Y. The filmmakers started shooting these sequences in late November, meaning they lost daylight around 4:30 p.m. Further, the building sat on the side of a hill, meaning the third floor was closer to six stories high, increasing the difficulty of controlling sunlight and re-creating it after the sun went down.

“To keep daylight going in there, we built light boxes for two sides [of the set], outfitted them with Kino Flos, hid the ballast up in the ceiling, and then put the boxes right into the windows as plugs, with vertical blinds in front of them to modulate the effect of a plain whiteout,” says gaffer Bill O’Leary. “On a third side, where Belfort’s office was located, was a window that offered an exterior view. Because that window was dominant in many shots, we decided not to white it; instead, we put a backing outside it. We used shipping containers to build [the frame for a wall] three stories high in the shape of an L, and we attached the backing to that [in tent fashion]. Then, we put a roof over it to protect it from the elements. We lit the backing with Arri X Lights on scaffolding that was just below the windows; then, we put up a Traveler truss rig and hung a 50K SoftSun to provide sunlight, along with two 12K Pars for the times when Rodrigo wanted a hotter splash in the background. So, we ended up with lights in both directions — lamps away from us to light the backing, and lamps toward us to light the set itself. It was the only way we could maintain a consistent daylight look regardless of the hour or weather.”

In addition to devising looks for different times and locations in Belfort’s story, the filmmakers also created certain looks to evoke the character’s emotions and/or mental state. For example, to highlight his ongoing drug abuse, Prieto devised “the Quaalude look,” getting up close and personal with DiCaprio as the actor delivered slurred-speech dialogue. “I used an Alexa with a 360-degree shutter at 12 fps, and then we printed each frame twice so the speed returned to 24 fps in real time, creating quite a bit of motion blur,” Prieto explains. “The image has the feeling of blur but also of flow, giving the sensation of being very loose. For one of these drugged-out scenes, in a nightclub, we also used Vantage Bethke Effect filters on the lens to add to the confusion. For another Quaalude scene, we used a Probe II Plus [from Innovision Optics] with a 20mm lens on it to get very close to Leo’s eye and mouth as he attempted to talk.”

In Belfort’s Manhattan apartment, Prieto used dimmable 4' MacTech LED tubes, mounting them on the top of the walls and windows around the perimeter of the rooms to bounce light off the ceiling. He loved the LED instruments because “I could use them to softly backlight the interior of the apartment, and because they’re dimmable we could set a very low level so the city lights would still register through the tinted windows at night. We shot those night scenes with the Alexa Studio, with the Master Primes wide open.”

A post-orgy scene in a Las Vegas hotel suite includes an overhead tracking shot of partygoers in various positions. This was shot on a built set, but no sidewalls were built because the camera only needed to travel over the top of the 50'-long suite, which comprised three rooms. Key grip Tommy Prate recalls that the crew created soft window light using 12'x12' frames of Full Grid Cloth with soft crates on them. “We had Arri T12s lighting through those frames,” says Prieto, “and outside the big window you see at the end of the shot we created sunlight with a 24K rigged on a truss over a large greenscreen.” The tracking shot was executed by placing a camera on the end of a 50' Technocrane on a 10'-high platform, permitting the camera to telescope straight without having to adjust the boom during the shot. As the shot ends, the camera booms down behind Belfort and looks out the window at a view of the city.

Such work is why Prieto calls The Wolf of Wall Street “a movie of extremes” in terms of what was required “to capture the energy Scorsese wanted.” The film also features several elaborate visual-effects sequences, including the crash of an all-CG helicopter in Belfort’s backyard. Without a doubt, however, the most complicated part of the entire production was a sequence in which a drug-addled Belfort sails his luxury yacht into the middle of a major storm as several characters struggle to survive on the bridge of the boat.

The filmmakers shot the live-action portions of the storm sequence on a yacht set that was built in the parking lot of Steiner Studios in Brooklyn. They had to create a believable dark and stormy day exterior, so Prieto decided to shoot the sequence at night to better control lighting. The bridge was built on a large gimbal that was shaken so violently it was frequently necessary for the dolly grips to latch onto Prieto and B-camera/Steadicam operator Maceo Bishop to help them stay upright as they captured the action.

O’Leary’s crew created soft ambient light for the sequence by bouncing 24Ks gelled with ¼ CTB off a 20'x30' frame of UltraBounce, and also with two 250K Lightning Strikes periodically going off as the gimbal thrashed. Meanwhile, the special-effects team used dump tanks and water cannons to send water onto the bridge of the set in order to simulate the wave that finally sinks the ship. A Chapman Hydrascope was used for shots looking into the bridge so that water could literally be dumped right over the camera.

For other scenes on the yacht, the art department built a replica of the upper deck of the boat in a soundstage at Kaufman Astoria Studios. There, all around the actors and crew, on the deck of the yacht, sat the fruits of what Prieto calls “a huge pre-rig” that was built in order to light and capture background plates. A semicircular greenscreen measuring roughly 50' high by 80' wide wrapped around the set, and it was rigged on a track so the crew could slide it to accommodate each shot without sending green spill to other areas of the set. Outside of shooting range, hung on the same truss, was a huge, white curtain that bounced light for a soft fill behind the camera. Lighting was complicated by the fact that the yacht set included shiny chrome, a lot of white, and low ceilings; this prevented O’Leary’s crew from hanging space lights to create ambient daylight.

O’Leary recalls, “The yacht was high on a platform, which didn’t give us much overhead space to work with, so we decided to basically lay in a blanket of Image 80s as high as we could get them and then stretch Full Grid Cloth beneath that. That rendered a broad, soft toplight. From there, we created sun for backlight using two 50K SoftSuns gelled with 1⁄2 CTO, one on a scissor lift and one on a Condor. Fortunately, the yacht was designed to have a structure over the top of the middle of the deck, and that enabled us to separate the light from the SoftSun on the Condor. That gave us a hard, distinct sunlight that we could use as a three-quarter backlight. We controlled many units with a DMX board so we could switch certain bulbs on or off.”

Another notable aspect of the shoot was the second unit’s work capturing aerial plates using a prototype of the Canon C500. Prieto tested the camera for more extensive use, but because it was still in the prototype stage and there were multiple Alexas available, he decided it was unnecessary. However, Legato found it ideal for the aerial work because of its small size and light weight; his team was able to rig it onto the nose of a remote-controlled Octocopter and fly it over beachfront property on Long Island. (Local rules prohibited the use of a full-sized helicopter in the area.) “The C500 weighs about 7 pounds, and the image quality was excellent, even with a prototype,” Legato says. “Using the Octocopter allowed us to get shots we couldn’t have with a normal helicopter.”

Throughout the shoot, Deluxe Laboratories processed the production’s negative and created dailies, scanning the negative at 2K and using Colorfront’s On Set Dailies for the timing, which was done in P3 log for Avid DNX115 dailies. Dailies colorist Steve Bodner applied viewing LUTs created by EFilm to the Alexa material that emulated Kodak Vision 2383 print stock. To communicate his creative intent to Bodner during the shoot, Prieto recalls that he “did basic CDLs on set for the Alexa footage using a viewing LUT from EFilm, and sent written notes for the scenes shot on film negative.” The cinematographer usually watched Blu-ray dailies at home on a calibrated monitor provided by Deluxe.

At press time, Prieto was preparing to commence the final grade at EFilm in Hollywood with colorist Yvan Lucas. EFilm New York did a 6K scan of the negative for this work, and EFilm Hollywood was set to do a 4K filmout.

Although Prieto had previously worked on somewhat similar terrain when he shot Wall Street: Money Never Sleeps for Oliver Stone (AC Oct. ’10), Scorsese’s project and methods were totally new experiences for him. “I learned a lot from him,” says Prieto. “I remember when [1st AD] Adam Somner and I first sat down with him and went through his shot list. Just listening to him explain why he wanted to use a static camera in a particular place, a mobile camera in a different scene, a big crane move, or whatever, was incredible. I felt like I was at some kind of an amazing seminar with a great professor. It was a great joy to build on his ideas and be a creative partner to such a brilliant mind.”

For more Martin Scorsese style, check out our look back at his work with Robert Richardson, ASC on the epic crime saga Casino (1995).