Brianne Murphy, ASC: Breaking Away

The career of this trailblazing cinematographer demonstrates challenges overcome by tenacity and talent.

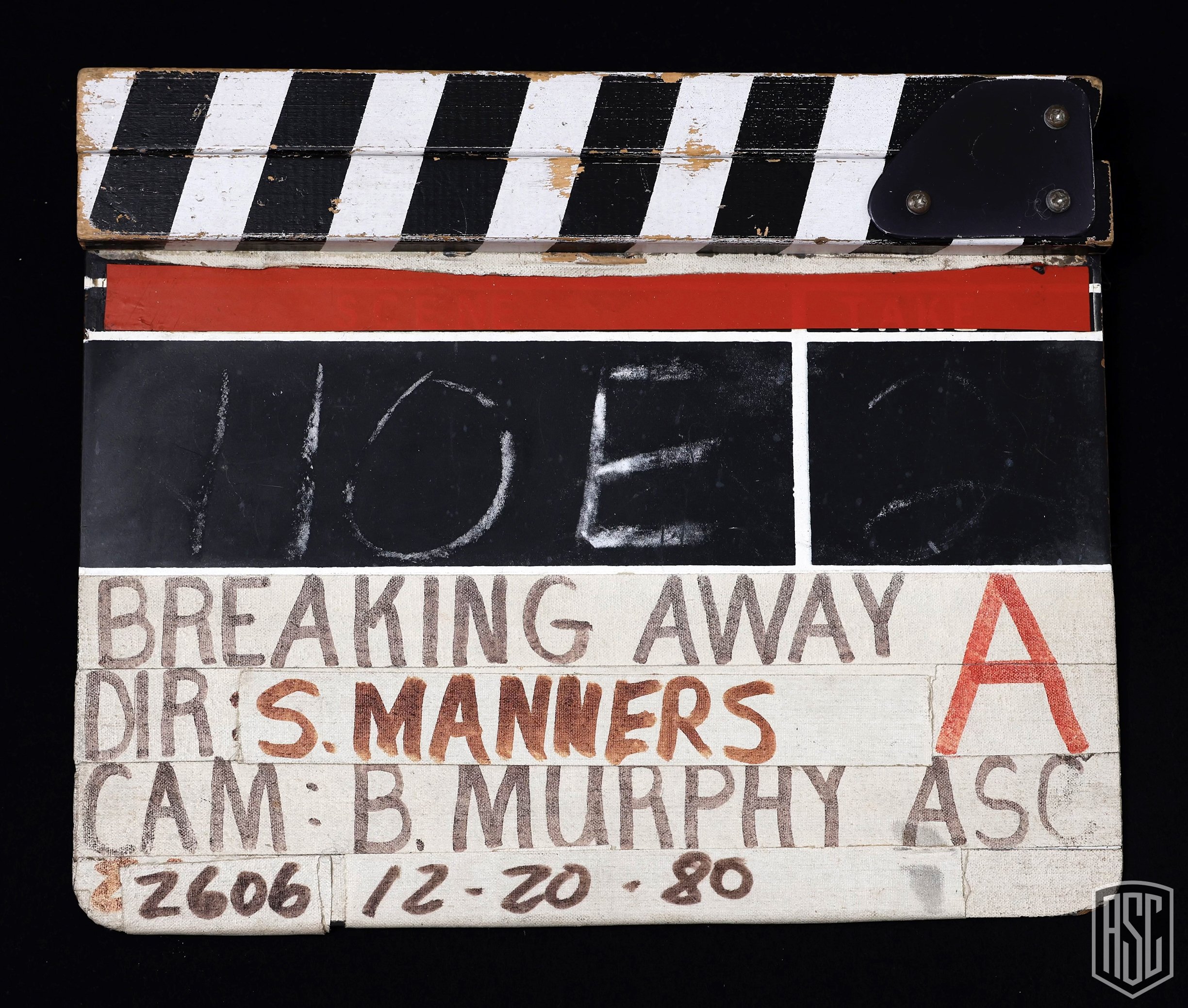

A new addition to the collection of cinematographic treasures at the ASC Clubhouse recently caught my eye.

This slate, dated December 20, 1980, was used during the production of the ABC network TV series Breaking Away, and notes that the cinematographer of this episode was Brianne Murphy, ASC — who became the first female member of the Society that same year.

How appropriate that Murphy would shoot this particular show, the story of an underdog driven by passion to be the best, and who would lead the way for others to follow.

Geraldine Brianne Murphy was born on April 1, 1933, in London, England, to American parents, but the threatened onset of World War II prompted the family to return to the United States. After attending Champlain College and Brown University, she joined the Neighborhood Playhouse in the mid-1950s to study acting. “I wasn’t crazy about acting, but I was crazy about show people,” she told AC in a comprehensive 1986 interview.

When On the Waterfront (1954) was filming in New York City, Murphy lingered around the set, hoping to learn something about the process. And she was soon recruited to run errands:

"One day the production manager asked me to take a Zeiss over to [the rental house] F&B and swap it for a Cooke. I said, 'Sure.' I didn't have the vaguest idea what he was talking about, but it was too good an opportunity to pass up. Of course, once I got over there, I asked, 'What's a Zeiss? What's a Cooke? And what's this thing in my hand?"'

Murphy's cinematic education had begun. As she further told AC:

"After a while, I got to know Kazan a little bit and he allowed me to stay and watch what was happening. I got an overall idea of all the jobs that were on the set. It never occurred to me that there were no women doing any of them. I looked around and decided I would like to grow up to be Elia Kazan directing a picture like On the Waterfront. But, the way that I would learn to do what he knew, was that I would be Boris Kaufman [ASC] — he was the cameraman. He was making the magic with this big black box."

Murphy observed the other people working on the set and got an overall understanding of what it takes to make a movie. Of all the possibilities — props, make-up, script supervisor — she kept in the back of her mind the idea that it would be nice to be a cinematographer. She followed On the Waterfront through postproduction. When the show finished, she went back to acting.

A year later, after learning the basics of still photography from department head Ted Sato while working for the Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Circus (another story for another time), Murphy arrived in Los Angeles. After a stint of shooting photos outside nightclubs on the Sunset Strip, she met indie producer Jerry Warren, who recruited her as a unit photographer on his low-budget genre movies, but, as is typical on such productions, Murphy was soon also doing hair, makeup and script supervising.

Murphy married Warren in 1956, and her cost-saving concept of shooting features back-to-back with the same actors and crew got her promoted to production manager, making cult classics including Teenage Zombies and The Incredible Petrified World.

When their marriage ended in 1959, she continued these duties on industrials and frequently hired herself as a second cinematographer. That later led to non-union feature-film camerawork. She sometimes used the name “Brian Murphy” just to get a foot in the door, then winning the job with her knowledge, experience and tenacity.

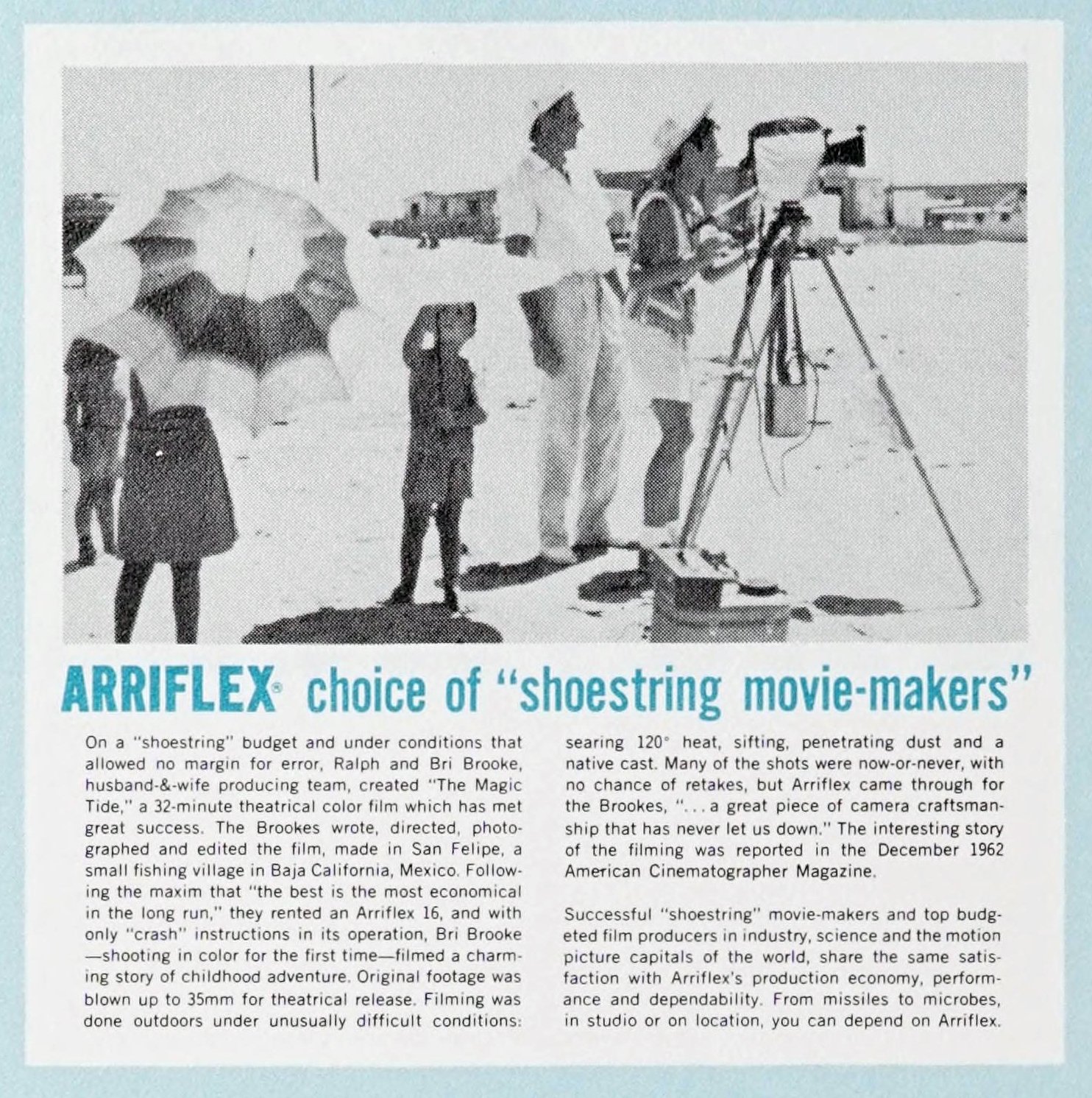

She married again, to writer-producer-director Ralph Brooke — best known for the horror film Bloodlust! (1961) — and soon co-founded Sombrero Pictures. One of their productions was the 32-minute short subject The Magic Tide, the making of which was detailed in American Cinematographer (Dec. 1962). With Murphy behind the camera (and also editing), they shot the project on 16mm in the coastal town of San Filipe in Baja California, Mexico:

On location, a number of pre-production tests were made, and one of the results was to indicate the advisability of using a Polascreen when shooting in the semi-tropical locale with its brilliant sunlight and to permit shooting at an f/ stop less than 16. The ASA rating of the color film used was reevaluated from 16 to 25, and it was further decided that, although it would involve some waste of film in edge-flare and run-off, 100-foot film loads would be used, which would permit more frequent inspection and cleaning of the camera’s gate, considering the dusty area in which the picture was to be shot.

This enterprising husband-wife team is presently producing another color film which they will offer as a 15-minute short, after which they plan to make another. Ralph and Bri Murphy Brooke are now firmly convinced that, in essence, having a story to tell and being able to tell the story well is still a pretty good formula for a successful motion picture.

After The Magic Tide was blown up to 35mm and had a successful theatrical run through Crown-International Pictures, the duo filmed a sequel short, Panchito and the Gringo. They then announced in June of 1963 that they would next produce a feature in Santiago, Chile.

They also appeared in this Arri ad, published in AC Aug., 1963:

But this chapter in Murphy’s life ended abruptly with Brooke’s sudden death on Dec. 4 at the age of just 43. And this tragedy only intensified her career focus.

She was soon working steadily as a cinematographer, in part because she had a knack for making connections. As she explained to AC:

"I found that with each picture I worked on, I met probably 10 new people. If you stay in touch with the 10 new people, a couple of them are going to know about another project. Things started snowballing. I was still the only woman working on any of these pictures. By this time, I had an apartment on Beachwood Drive in Hollywood. I insisted on living right under the Hollywood sign. Every day after work, since my place was central, we would all get together for a cup of coffee or a glass of beer or something and talk about the day and what was coming up. The word hadn't been invented for this yet, but we were networking.”

A woman working in a male-dominated industry, Murphy encountered plenty of roadblocks. As she related, one camera union officer told her: "My wife doesn't drive a car, and you're not going to operate a camera. You'll get in over my dead body." But she was eventually able to join the camera guild as a first assistant. What had changed? “He died,” she told AC.

Soon after, NBC contacted the union in search of a female cinematographer to shoot a documentary about breast cancer. The guild granted Murphy a waiver so she could take the job. NBC was impressed with her camerawork, and she was soon busy shooting news segments, specials and documentaries.

Murphy’s major career break came in 1975 when Richard C. Glouner, ASC — who had just won an Emmy for the hit detective series Columbo — had to leave the show in the midst of production and was told by the studio to find a replacement behind the camera who could do the same quality of work. As Murphy told AC:

“He said that there was only one choice: Bri Murphy. [The studio then asked,] 'Okay, what's his number?' Glouner said, 'Well, I hope you don't hate your mother, because it's a woman.' They said, 'No way are we going to put a woman on a sound stage at Universal.' Glouner said, 'Then I'm not picking anyone. Bri is my choice.' Well, they were afraid not to go with me because an Emmy for Columbo was rather important, I guess."

With Columbo, Murphy's career as a director of photography was established. "My sister asked, 'Well, what's the big difference between what you were doing and what you're doing now?' I said, 'For some reason, now people laugh at my jokes."'

Glouner’s vote of confidence led Murphy to more opportunities. In 1977, she won an Emmy for the NBC Special Treat episode “Five Finger Discount.” She then went on to shoot episodes of series including Mulligan’s Stew, Wonder Woman, Breaking Away (earning an Emmy nomination), Square Pegs, and In the Heat of the Night. She also shot telefilms including There Were Times, Dear (earning another Emmy nomination) and Kung Fu: The Next Generation.

When actor Anne Bancroft made her directorial debut with the 20th Century Fox comedy Fatso (1980), she hired Murphy as her director of photography. It was the first time a woman held that position on a major studio release.

After Murphy was invited to join the ASC that same year, she later served on its Board of Governors for multiple terms.

After several crew people were killed while filming stunts that went awry, Murphy and two other cinematographers formed the Ad Hoc Safety Committee — consisting of representatives of Local 659, Stunts Unlimited and the Stuntman’s Association of Motion Pictures — to put an end to safety compromises on sets.

Inventive, Murphy designed the MISI Camera Insert and Process Trailer, a breakthrough device that enabled cinematographers to film subjects in moving vehicles without jeopardizing their own safety. This earned her an AMPAS Scientific and Engineering Award Plaque in 1982 (shared with veteran insert car driver Donald Schisler).

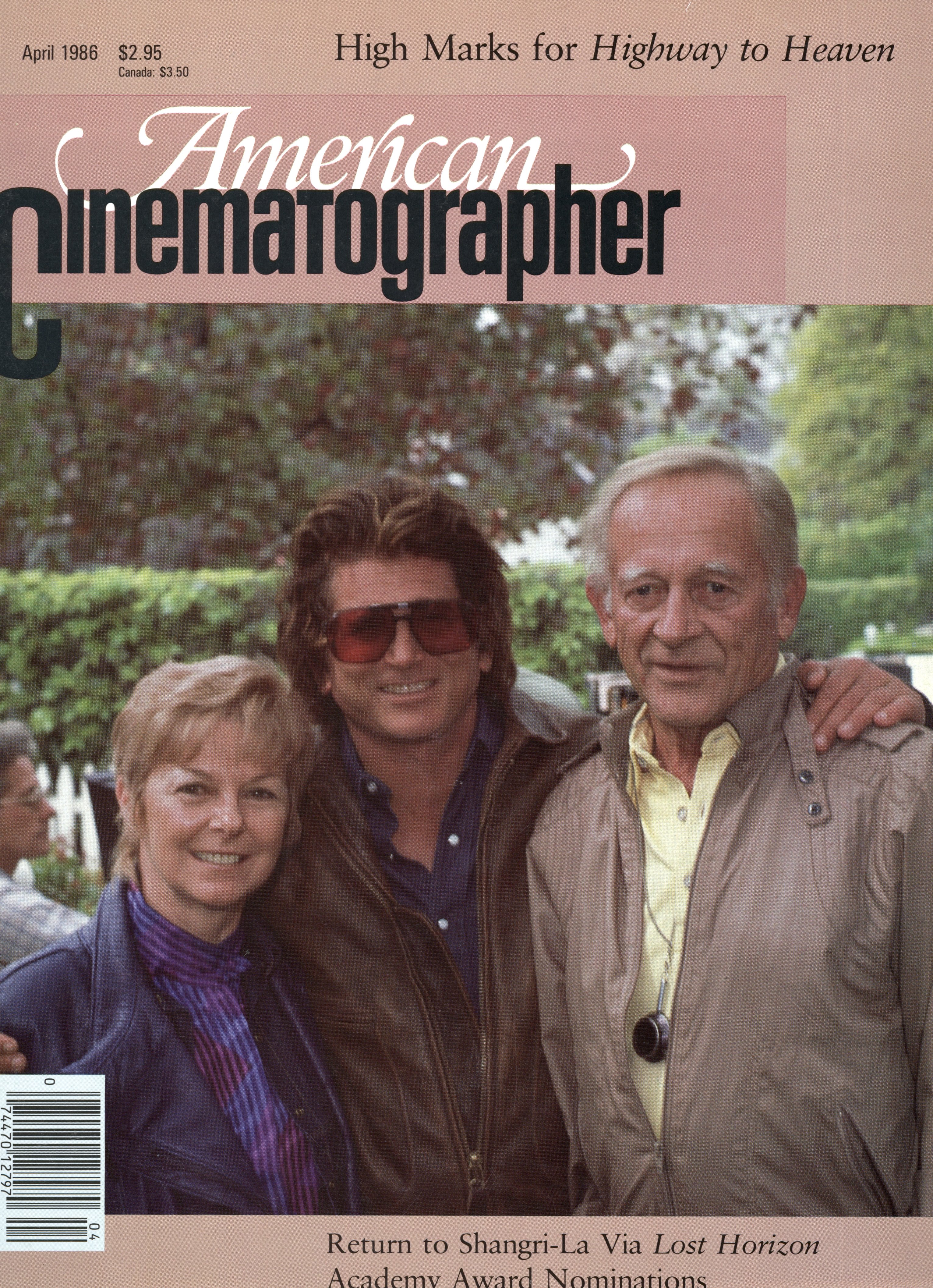

Murphy shot more than 40 episodes of the network drama Highway to Heaven — trading off with Ted Voigtlander, ASC, who had recommended her for the job — and collaborating closely with executive producer-director-star Michael Landon — with whom she previously worked on the shows Father Murphy and Little House on the Prairie.

She earned an Emmy nomination for her camerawork in the 1985 Highway episode “A Match Made in Heaven,” and the trio was featured together on the cover of our aforementioned April 1986 issue of AC, shot by Gene Trindl:

Away from the camera, Murphy was a co-founder of Women in Film and NABET, the TV technician’s union. She also served a term as president of Columbia College in Hollywood.

Recognized with the Crystal Award (1984) and Lucy Award (1995) for her excellence, Murphy’s innovation and her leading role in opening up new professional avenues for women in entertainment remains influential and inspiring.

All that in mind, this slate from Breaking Away is all the more appropriate as a memento from Murphy’s career. It was generously donated to the ASC by cinematographer Jeff Barklage.

Murphy died of cancer at the age of 70 on Aug. 20, 2003, in Puerto Vallarta, Mexico.