Burn After Reading: Fahrenheit 451

Kramer Morgenthau, ASC and director Ramin Bahrani welcome AC to the set of this dark update of Ray Bradbury’s classic novel.

Unit photography by Michael Gibson, courtesy of HBO.

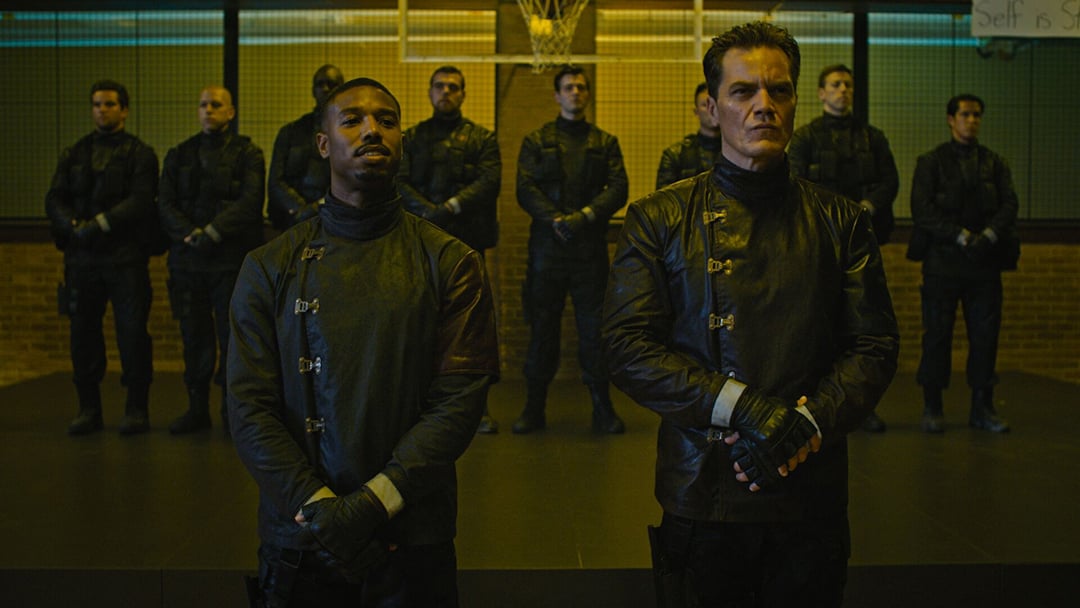

In the dystopian, near-future America depicted in the HBO movie Fahrenheit 451, books are verboten. Civil war has left 8 million dead, and a tech-based ruling Ministry looks to squash divisiveness by also banning movies, the arts and the free press — anything that might promote a contrasting viewpoint. All information is now disseminated through a state-controlled electronic network called the Nine, and citizens are monitored through a smart-home system called Yuxie, which prescribes drinks and eye-drops that cloud people’s memories and keep them believing the Ministry’s propaganda. Firefighters are tasked with starting fires rather than extinguishing them; singing marching tunes, they violently track down violators, burn their books with flamethrowers, and erase their online identities. The punished, called Eels, become outcasts, unable to travel or access funds.

In Cleveland, fireman Guy Montag (Michael B. Jordan) is being groomed for promotion by his mentor, Capt. Beatty (Michael Shannon), the head of fire department 451 — the number representing the temperature at which paper burns. Privately, Montag and Beatty are each obsessed with the forbidden written word, and in Montag’s case this is amplified by his interest in Clarisse McClellan (Sofia Boutella), a literature-loving Eel who nonetheless trades information about book hoarders for favors from Beatty.

When one of McClellan’s tips leads to a tragic raid on an old woman (Lynne Griffin), Montag can’t help but be moved by the Eels’ willingness to sacrifice everything in defense of their passion for books. His loyalties become torn between Beatty and the Eels, the latter of whom have devised a plan to spread knowledge from all recorded works and usher society out of its collective darkness.

“[Kramer] did character-driven indie films and then made a big jump into larger studio projects that involve visual effects and more stylized work. I was looking for someone who could both focus on character and bring style.”

Based on author Ray Bradbury’s classic 1953 novel, the movie was directed by Ramin Bahrani and photographed by ASC member Kramer Morgenthau. AC visited the filmmakers while they were shooting in Toronto last September, on day 41 of their 43-day shoot.

It is the second day shooting in the Cranfield House, the 1901 mansion that recently had a starring role in the horror blockbuster It (AC Oct. ’17). For Fahrenheit 451, the building is being used for several interiors, including McClellan’s run-down loft. (The day before, the production received unexpected guests when a number of raccoons suddenly emerged through a wall.)

Bahrani — whose previous credits include the features Man Push Cart (AC May ’06), Chop Shop, Goodbye Solo and 99 Homes (AC Oct. ’15) — says he was inspired to adapt and modernize Bradbury’s story in 2015, when he sensed a change in the political climate. “As Bradbury wrote, we demanded a world like this,” the director says, sitting on a padded apple box by a Sony monitor and echoing dialogue from the script he co-wrote with Amir Naderi. “We elected things to become this way. We decided to give all our information away. We decided to read news on Facebook, which tells us exactly the news we want to read.”

He points to other prescient aspects of the novel, such as wall-sized TV monitors and “Seashells” — earphones that dial in popular music, entertainment and news. “Today you could burn a book, but I might have 10 million books in this supercomputer,” Bahrani continues, holding up his smartphone. “Students today would say, ‘Every book ever written is here, and I can Google any information I want.’ So that starts getting monitored and controlled. The movie has to deal with the reality of today.”

“I thought having nearly the entire film at night would create this amazing mood and atmosphere.”

Due to unforeseen circumstances, Bahrani found himself in Toronto a couple of weeks ahead of production without a director of photography. Len Amato, president of HBO Films, recommended L.A.-based Morgenthau, whose credits include the HBO projects Boardwalk Empire (AC Sept. ’10), Too Big to Fail (AC Nov. ’11) and Game of Thrones (AC May ’12), and features such as The Express (AC Oct. ’08), Thor: The Dark World (AC Dec. ’13) and Chef (2014). “Kramer’s lineup includes human dramas and documentaries, which means character focus,” Bahrani notes. “He did character-driven indie films and then made a big jump into larger studio projects that involve visual effects and more stylized work. I was looking for someone who could both focus on character and bring style.”

Morgenthau recalls that he was shooting a commercial in L.A. on a Thursday when he was reached by Ginny Nugent, HBO’s senior vice president of production. “She said, ‘There’s no prep. Can you be there tomorrow?’ And I said, ‘I could be there next Wednesday.’ I wasn’t excited about how last-minute it was, but I loved Ramin’s films, and Fahrenheit 451 is an iconic piece of literature. I told them I would just hit the ground running.”

Morgenthau interviewed with Bahrani via FaceTime, then began reviewing location photos forwarded by the director as well as production designer Mark Digby. Bahrani also referenced Orson Welles’ Touch of Evil (photographed by Russell L. Metty, ASC) and The Trial (shot by Edmond Richard); the influence of both movies can be felt in Fahrenheit’s shadowy characters framed within nocturnal landscapes.

Fahrenheit 451 was also adapted for the screen in 1966 by director François Truffaut, who worked with cinematographer — and later director — Nicolas Roeg, BSC. Morgenthau maintains that the earlier movie did not affect his approach. “It’s pretty campy-looking now,” he opines. “It’s very broad-lit. I don’t think there’s a shadow in the entire movie even though there’s fire. It’s a 1960s version of futuristic, which is cool, but we aren’t doing futuristic. Ramin went back more to the book to write his screenplay.”

When Morgenthau finally arrived in Toronto, it was 1 a.m., and six hours later he was on a bus heading out for the first day of a three-day tech scout. Easing the transition was 1st AC Russel Bowie, who had already been prepping Fahrenheit 451 for weeks, and with whom the cinematographer had previously photographed three features, most recently the thriller The Factory (2012).

While prepping the feature, Bahrani shot every scene on his phone with stand-ins, but once production began, he encouraged input from Morgenthau and the entire cast and crew. “You want to make sure you’re filming a scene actually worth filming,” the director says about the process. “If it is worth doing, then I say, ‘Kramer, I imagine these shots. What do you have in mind?’”

Save for one scene, Bahrani has set all of the movie’s action at night. “In the novel, book-burning happens at night for the show of it,” the director explains. In his adaptation, this primetime “entertainment” is broadcast on the side of city buildings for crowds on the street. “I thought having nearly the entire film at night would create this amazing mood and atmosphere,” he adds. “It’s hard to show shifts of time when you don’t have day and night reference points, but I thought that would add a unique quality.”

“We’re going for a more ambient, natural-light look. We want to look in many directions with just available light.”

Because of the nighttime setting, and because Bahrani wanted the flexibility to shoot almost 360 degrees for most scenes, Morgenthau felt Panasonic’s VariCam 35 — with its 4K, Super 35mm sensor, and its 800 and 5000 dual native ISO — would be the ideal camera. “I chose VariCam for its light sensitivity at night,” says Morgenthau, who had heard positive feedback about the camera from fellow ASC member Theo van de Sande. Working with Panavision, the production arranged camera tests over the July 1 Canada Day weekend — less than a week ahead of principal photography. “Panavision bent over backwards,” Bowie says.

Standing by digital-imaging technician Jasper Vrakking’s Flanders Scientific CM250 24.5" 10-bit OLED monitor, Morgenthau presents a “flip book” of what has been shot over the course of the production. He explains that he wanted to shoot the movie’s exteriors — some of which were shot in the nearby steel city of Hamilton — with existing urban sources; for such scenes, he would set the camera’s ISO to 3200 in order to yield less noise than 5000 would produce.

“We’re going for a more ambient, natural-light look,” the cinematographer notes. “We want to look in many directions with just available light. Once you’re into the 3200 ISO space, every practical is a source — and there is plenty of light for us. This camera sees way beyond what the human eye does. We did bring in some lighting, but more for the foreground; I try to avoid big backlights at night. Ramin likes us to work with a small footprint and be fast on our feet.”

Morgenthau’s go-to source for ambient light in the foreground has come from a rig custom-built by Dwight Crane, working with key rigging grip Jon Billings, that features a condor rigged with four Arri SkyPanel S60s. The SkyPanels, in turn, are controlled remotely via the Luminair lighting-control app, and are diffused through a 12' x 12' frame of Full Grid fitted with a Lighttools egg crate; an LRX mechanized tilting system allows the crew to remotely angle the frame.

To further help the low-light shooting, Morgenthau has paired the VariCam 35 with Panavision Super Speed and Ultra Speed legacy primes, and worked at a stop between T1.4 and T2. He notes that these lenses also “soften the digital quality without using diffusion — it’s like the diffusion is built into the lens.” The only filtration the cinematographer has used for the shoot are NDs, and predominantly only the ones that are internal to the camera.

“I was thinking about color as a character. In my mind, all those washes of color [come from] Big Brother trying to control people’s moods.”

The 29mm and 40mm primes have been the crew’s workhorses. “Ramin likes a wide-and-close filmmaking style, where it feels like you’re there with the actors, but he doesn’t want to be so wide that the lenses are distorting,” Morgenthau explains. “His mantra is that we always want to be in Montag’s head.”

This mantra is taken to an extreme for Montag’s flashback memories of his father, a deceased fireman whom Beatty regards as a hero. For these shots, Morgenthau employed a Lensbaby Composer Pro for selective focus. “It gives a dreamy, myopic, point-of-view feel that’s different from the rest of the movie,” Morgenthau says.

One of Fahrenheit’s most arresting visuals is the recurring point of view from the Yuxie devices, revealing what Big Brother sees as it monitors Montag and the firemen. The 360-degree view was created with six GoPro Hero4 Black cameras mounted in a GoPro Omni rig; Vrakking stitched the six images together into one frame:

For crane work — with 15', 30' and 50' Technocranes, and Libra remote heads — the crew has used 15-40mm (T2.6), 19-90mm (T2.8) and 24-275mm (T2.8) Primo Zooms, all detuned to better match the legacy primes. Bahrani says that coming from the indie world, cranes hadn’t been a big part of his language, but he’s warmed to them as the crew has put them to use for such scenes as a firehouse exterior, a raid that removes computers from an Eel house, and McClellan’s meeting with an informant in front of a power plant.

The production is recording 3840 x 2160 files with AVC-Intra compression, capturing to Panasonic ExpressP2 memory cards, and often taking advantage of the VariCam 35’s ability to shoot up to 120 fps, over-cranking for slow-motion shots of fire. The UHD resolution, Vrakking offers, has suited the production well, “even for the amount of visual effects we’re going to have. In the tests, it had enough resolution and color depth for visual effects to do what they need. In order to shoot raw, we would have had to add a Codex [recorder], and there are so many handheld and Steadicam shots that [doing so] would have taken away from the production more than we would have gained.”

Morgenthau and Vrakking worked with EFilm to create two main LUTs for the movie, one for the firemen’s world and another for the Eels’. Building on those LUTs, Vrakking is working with Pomfort’s LiveGrade on set to adjust color shot by shot, which he says is necessary given the quirks of the older lenses.

“You send this tiny drone up and quickly get these amazing shots — it’s such a different perspective. It’s unbelievable.”

Vrakking describes the Eel LUT as “warmer, with a little more saturation. We’re shooting in old buildings that look like slums, so we’ve made it muddier and grainier in the shadows.” The firemen’s world, on the other hand, is sleek and has been shot largely with smooth dolly moves lit with colored practicals. “I was thinking about color as a character,” Morgenthau says. “In my mind, all those washes of color [come from] Big Brother trying to control people’s moods.”

To integrate that colored light into the sets — such as the interior of Montag’s house, which was built on stage at Cinespace Film Studios in Toronto — gaffer Michael L. Hall and his crew worked with Moss RGBAW LED strips built into diffusers. “We could change the strips to whatever color [was needed],” Hall says. Red and blue were the colors of choice for Beatty’s sparse office — and in Montag’s house, Hall adds, “we made it what Kramer calls ‘tequila sunrise.’ It’s like urban vapor but warmer. It’s a nice color we used quite a bit.”

On locations such as the Brutalist University of Toronto Scarborough campus, which provides exteriors and interiors for the firehouse setting, Hall’s team installed fluorescent tubes with colored gels. The hallways, appropriately, are overpoweringly red, while in a basement where Montag and Beatty spar, the crew mixed Jade with Medium Yellow.

Beatty and Montag meet with McClellan at a VR bar, where patrons interact with headsets rather than one another. The sequence was staged in Toronto’s historic Design Exchange building. In the main space, the crew positioned Chroma-Q Color Force 12 LEDs set to a cool-blue hue behind windows running up the wall and across the ceiling; visual effects would later replace the windows with video panels that display swirling colors. Martin Professional VDO Sceptron fixtures — LED tubes pixel-mapped with color effects — were placed to add further movement to the room, as were Clay Paky B-Eye wash lights.

The two firemen find McClellan by the cream-hued bar, which was lit from below by four 4' 4Bank Kino Flo units with Medium Yellow gel. Behind the bar, a large pink neon sign reads “Stay Vivid,” and shelves of bottles are lined with colored LED strips. McClellan, Beatty and Montag then move to a smaller back room, where they talk in front of a 10' x 6' video wall provided by Solotech that displays swirling pink patterns; dialed-down LiteGear LiteMat 2Ls provided fill from either side.

The Eels’ homes and hideouts, by comparison, are lit by low-tech tungsten practicals and shot with a handheld camera. The old woman’s country-house interior, shot on set, features various wall sconces, lamps and chandeliers with 60-watt bulbs; these sources motivated Morgenthau’s use of 650-watt fixtures and LiteMat 1 units. A SkyPanel S30 or S60 provided fill. For the segment when the book burning begins in the home, a fire was set in the foreground, with the actor a safe distance behind it. Flame bars were positioned in front of the camera, and SkyPanels were programmed with a fire effect.

The crew ran three cameras for that particular book-burning scene, but most often two cameras have been used simultaneously, with Michael Heathcote operating A camera and Steadicam, and Ian Anderson on B camera. Anderson has also served as 2nd-unit cinematographer, shooting plates, atmospheric footage and inserts.

As AC’s visit continues, the crew prepares a scene in which McClellan comes home and reassembles an old portable cassette player that she will exchange for information. Her decrepit, white-walled apartment has been created in a part of the Cranfield House that looks like it might have been a parlor. An off-camera window has been blacked out, and Hall has rigged one 4' x 4' Sourcemaker LED Blanket to the ceiling for top light, and a second in an adjoining room, with some of that light spilling in through a doorway. Both cameras are set for 800 ISO.

“Kramer was going for a bold image with rich blacks, and shaping the image with custom vignettes. We also wanted to retain detail in the fire as best as we could.”

The edited scene will begin with a shot of a classical record spinning on a turntable; the camera pans over to McClellan’s desk, where she solders the cassette player. A mechanic’s light, fitted with a 60-watt bulb, lies on her desk, facing the camera and providing much of the scene’s illumination.

There is a moment in the scene when McClellan looks up to a shadeless window and hears a drone outside — one of the Ministry’s tools for keeping tabs on off-the-grid neighborhoods. For this scene, the drone’s presence is suggested with a sound effect and a beam of light from an 800-watt Jo-Leko HMI, but real drones figure prominently throughout the movie, appearing on camera, for example, as they light the way for fire trucks. The drones were fitted with custom 300-watt LED spotlights and provided illumination from on and off camera; Chris Bacik’s Sky Eye Media provided these custom-built lights and Spyder octocopters. “Chris sourced all the drones,” says Morgenthau. “On our bigger drone nights, other companies’ drones would also be used, but Chris was in charge.”

“I spent weeks finding a deflector that would give us the beam we wanted,” Bacik says via email, describing the LED light source that was rigged to the Spyders. “I ended up using a tall plastic drinking cup with a chrome finish that I added inside.” The resulting fixture could mount to the drone’s camera stabilizer, allowing the drone operator — who monitored a feed from a GoPro mounted above the light — to point the light in any direction.

A DJI Inspire 2 drone was fitted with a Zenmuse X5S Micro Four Thirds camera to shoot aerial views, such as a high establishing shot of the farmhouse. “Those images look awesome and match well,” Morgenthau says. “You send this tiny drone up and quickly get these amazing shots — it’s such a different perspective. It’s unbelievable.” Sometimes the crew had two lighting drones and one camera drone on the same shot; the 4K X5S recorded 12-bit raw in Log format to onboard SSDs.

Working out of sequence, the crew prepares to shoot McClellan’s entrance into her apartment. Boutella walks toward camera, down a narrow hallway that has been boarded-up in places, and beneath a couple of hanging 60-watt fixtures that are supplemented by S2 LiteMat 2L units fitted with egg crates and positioned along the ceiling. Heathcote handholds the setup’s lone camera with an attached obie light for an eye light.

McClellan knocks on a neighbor’s door. A young mother answers, holding a baby, and McClellan hands her a bottle of milk. The woman thanks her and then warns, “Careful what you’re selling. People are talking.” McClellan moves on to her own door, opens it, and the glow from a Sourcemaker LED Blanket spills out.

A discussion ensues about the believability of the baby doll that’s being used for the scene, particularly in a medium shot. Bahrani decides a real baby is necessary, and the call goes out to bring one over. Meanwhile, Hall asks his team to lessen the atmosphere, and Morgenthau turns off one of the overhead bulbs.

“Ramin put a tremendous amount of thought into it, and I brought a different set of eyes, and we’ve really melded on it.”

The baby arrives, is wrapped in a blanket and handed to the actor. The real baby presents its own challenges, crying at inopportune moments, but soon Bahrani is satisfied with a take. The filmmakers move on to another scene in the same location, in which McClellan sneaks Montag into her apartment, and soon thereafter the day draws to a close.

Months later, after the picture was locked, Morgenthau and EFilm colorist Tim Stipan reviewed the movie in Los Angeles to discuss the look. Then, along with Bahrani, they spent a week working on the digital color grade at Company 3 in New York. The final grade was finished remotely, with Stipan in L.A. and Bahrani in New York. Grading with Blackmagic Design’s DaVinci Resolve and referencing Sony BVM-X300 and Panasonic EZ1000 monitors, Stipan made a P3 theatrical version for delivery to the Cannes Film Festival as well as an HDR version.

“Kramer was going for a bold image with rich blacks, and shaping the image with custom vignettes,” the colorist explains via email. “We also wanted to retain detail in the fire as best as we could.” Stipan enhanced colors in the firemen’s world and muted some for the Eels’ scenes. The exception was the lone scene that takes place during the day, when Montag joins the Eels at a farmhouse; for this scene — which was originally planned as a night shoot, but was forced into daylight due to a tight production schedule — Stipan boosted the color contrast.

“For the most part we are ‘printing’ things down, making [the images] richer and more nuanced,” Morgenthau adds in a follow-up call. “We’re using lots of windows to darken parts of the frame, which I pretty much always do, bringing down walls and maybe bringing up a face. We also added some 16mm grain to shape the flashbacks.”

Morgenthau admits he wasn’t sure what to expect joining the production at the 11th hour. “But sometimes it’s the best thing ever,” he says. “Ramin put a tremendous amount of thought into it, and I brought a different set of eyes, and we’ve really melded on it. It’s one of the better experiences I’ve had in years. It brought me back to my roots of independent filmmaking and re-inspired my love of cinema.”