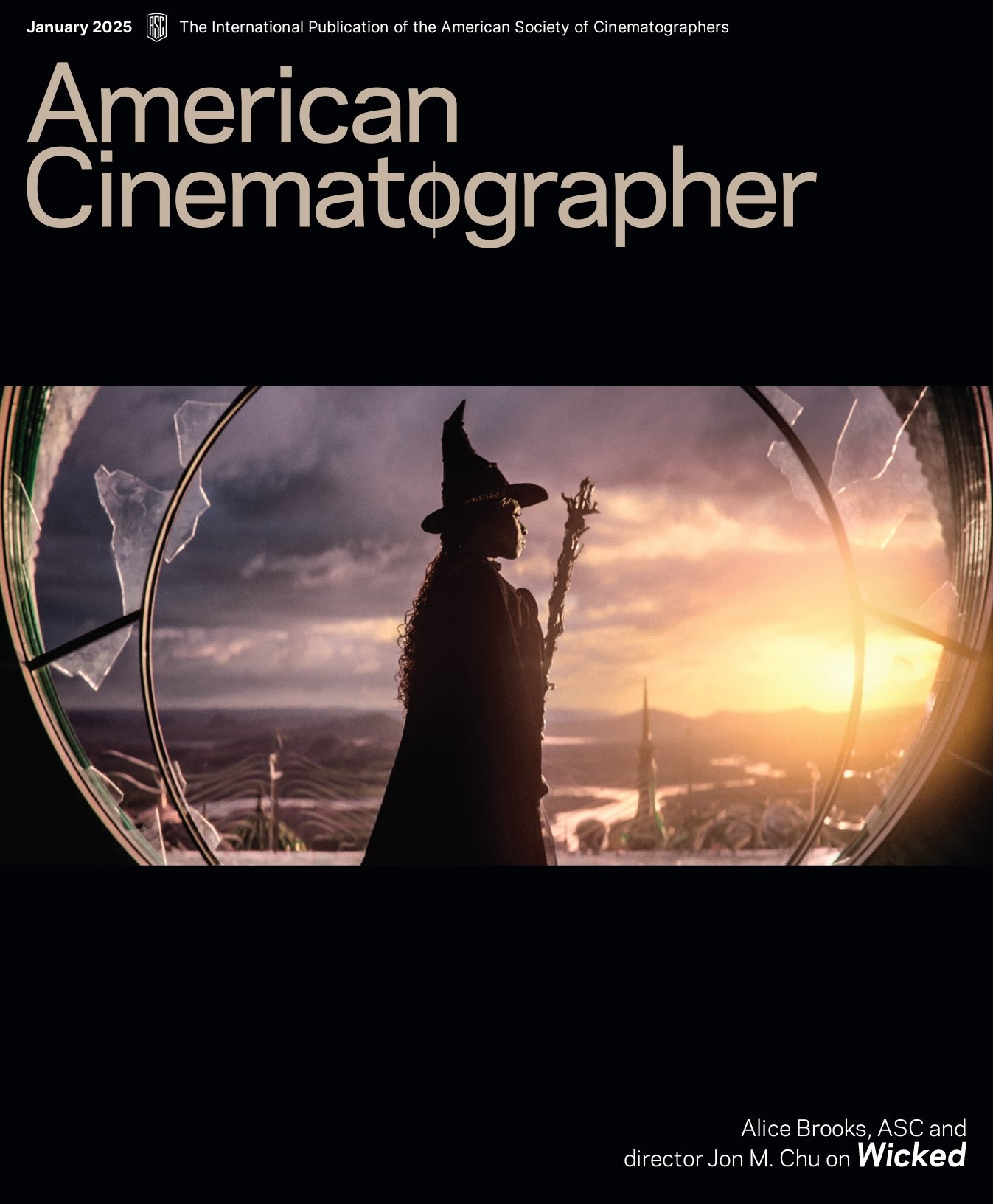

The World of Wicked

ARTICLE EXCERPT: Alice Brooks, ASC and director Jon M. Chu capture the hues, textures and emotions of Oz.

The long-awaited motion-picture musical Wicked marks the most ambitious and challenging production to date for longtime collaborators Alice Brooks, ASC and director Jon M. Chu. Massive sets, prototype lenses and thousands of lighting cues — and their “own version of Technicolor,” as Brooks describes the palette — were deployed to realize the feature-film adaptation of the lauded Broadway hit.

Yet, even on this grand scale, the filmmakers’ starting point remained the same. “When Jon and I first discuss a project, it is all about humanity,” the cinematographer says. “We know the technical details will come in time, but the emotion is what we ultimately care most about. With Wicked, Jon asked what my goal was, and I said the film would be the most beautiful love story ever — between these two women, these two best friends.”

This intention informed every creative and technical decision — from lens choices, to camera movement, to 360-degree shots, as well as the extensive lighting design. Central to Brooks’ overall approach was a commitment to ground the story’s fantastical elements in a tangible reality.

Chu recalls asking, “‘What is our version of Oz? [If] you could do anything, how far do you want to go? How do you want it to feel?’ All of us got together and said, ‘Let’s make it touchable.’”

Based on Gregory Maguire’s 1995 novel Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West — a prequel to the 1900 L. Frank Baum novel The Wonderful Wizard of Oz and its classic 1939 film adaptation — Wicked adds to a long creative legacy. As in the live production, first staged in 2003, the film explores the relationship between Elphaba (Cynthia Erivo), the future Wicked Witch of the West, and Galinda (played by Ariana Grande, and referred to hereafter as “Glinda,” as she’s known later in the narrative), the future Good Witch, who meet at Shiz University, where their respective fates become intertwined.

The kinetic visual style Chu and Brooks demonstrated on such works as The LXD (AC Oct. ’10) and In the Heights (AC Aug. ’21) made the duo a natural fit for the project. Although the visuals of Wicked are partially rooted in the 1939 film, and inspired by the vivid descriptions of color in Baum’s original Oz novels, Brooks and Chu endeavored to bring an aesthetic vision of Oz all their own. Drawing from a creative partnership cultivated over the last 20 years — one that began with their days together at the University of Southern California School of Cinematic Arts — Brooks and Chu relied upon their well-developed shorthand and shared vision to bring Wicked’s narrative to life.

Grounding the Land of Oz

The filmmakers’ desire to make Oz “touchable” manifested in minimizing the use of bluescreen in favor of practical sets — the vast scale of which, Brooks says, recalled moviemaking of old. “We wanted to make an old-Hollywood film like Spartacus or Cleopatra, with real, tangible spaces to shoot,” she says. “With the scale of the sets, we really had our work cut out for us. Along with the electric team, we pre-lit every weekend for the next week’s work. I took a total of seven days off over our eight-and-a-half months of filming, with a 155-day shooting schedule.”

The film’s scope — including the Emerald City and Shiz University sets, each of which called for a footprint the size of four American-football fields — required Wicked to occupy a total of 17 stages at three London studios: Leavesden, Platinum Stages and Sky Studios Elstree. With additional space still needed, the production also rented a farm in Ivanhoe, outside London, to build four major backlot sets.

“It was very important to go old-school, big build,” says production designer Nathan Crowley. Interior sets filled entire soundstages, providing 360-degree environments to light and photograph, with Brooks noting that “the sets went from the stage floor to the reds and from fire lane to fire lane.”

Unreal Engine previs was employed nine months before scenes in the expansive tulip fields of Munchkinland — assembled in Norfolk, England — were scheduled to shoot. The production planted nine million tulips for these expanses, featured in the second scene of the film, through which children run toward the center of town, cheering that the Wicked Witch has been declared dead. Says Brooks, “We needed to work with the tulip farmer to rotate the orientation of how he normally planted bulbs, by something like 30 degrees, so that the sun would line up the way we wanted it to for the shots — including one in which Glinda is backlit in her bubble.”

The filmmakers’ conversations with the farmer began in August 2022, and the tulips bloomed in April 2023.

“We wanted as much ‘groundedness’ as we could get,” Brooks explains. “Even though the movie features visual effects, our intention was to capture as much in camera as possible and make a film that feels handmade. For example, in addition to planting the millions of tulips and a barley field, we also built the train that transports Elphaba and Glinda from Shiz University to the Emerald City. It was 15 feet tall and 150 feet long, weighed 42 tons, and actually ran on tracks.”

You’ll find the complete story in our January 2025 issue. Subscribers can finish this story now by logging in to our digital edition. Not a subscriber yet?

Become one today.

The cinematographer also discussed the film in this episode of ASC Clubhouse Conversations, with interviewer M. David Mullen, ASC: