A Remake That Can’t Miss: Cape Fear

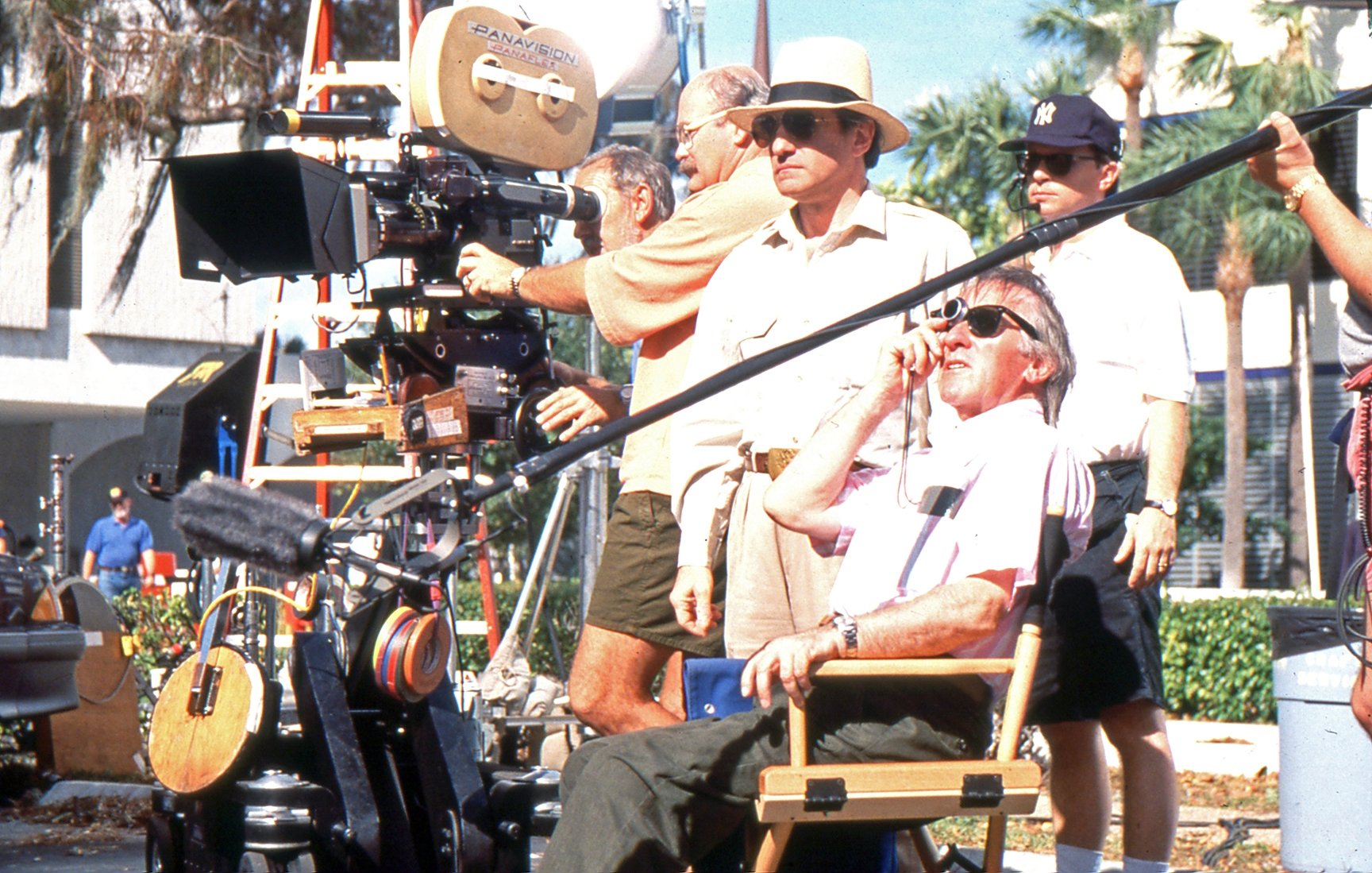

Cinematographer Freddie Francis, BSC discusses the challenges of recreating a classic.

This article was originally published in AC, Oct. 1991. Some images are additional or alternate.

Martin Scorsese's films contain many homages to classic motion pictures — the techniques of influential directors often find new applications under his inventive hand. With his latest picture, Scorsese takes that trend one step further by remaking the 1962 thriller Cape Fear, which was directed by J. Lee Thompson and photographed by Sam Leavitt, ASC. A vigilante picture which met with some scathing criticism in its day (due to its violence and what some termed its “amorality”), the original has become a recognized classic.

Adapted from a John D. MacDonald novel, The Executioners, the original Cape Fear starred Robert Mitchum as the psychopath Max Cady. Released from prison, Cady seeks to exact revenge upon Sam Bowden (Gregory Peck), the attorney he blames for his incarceration. Cady's unsettling presence haunts the lawyer and his family, who, trapped in their own home, expect the ex-con to descend upon them at any moment. Finally escaping to the apparent isolation of the Cape Fear River, the Bowdens find their weaknesses and insecurities exposed when they must resort to violence to restore order.

Scorsese’s remake, produced for Universal Pictures by Steven Spielberg's Amblin Entertainment, stars Robert De Niro as Cady and Nick Nolte as Sam Bowden. The cast also features Jessica Lange, Joe Don Baker and — in cameo roles — Peck, Mitchum, and Martin Balsam.

Scorsese was interested in recreating the tension and atmosphere of an old-fashioned melodrama while incorporating the edginess and “hyper-reality” (his term) that distinguished his work on previous efforts such as Taxi Driver, Raging Bull, After Hours and GoodFellas.

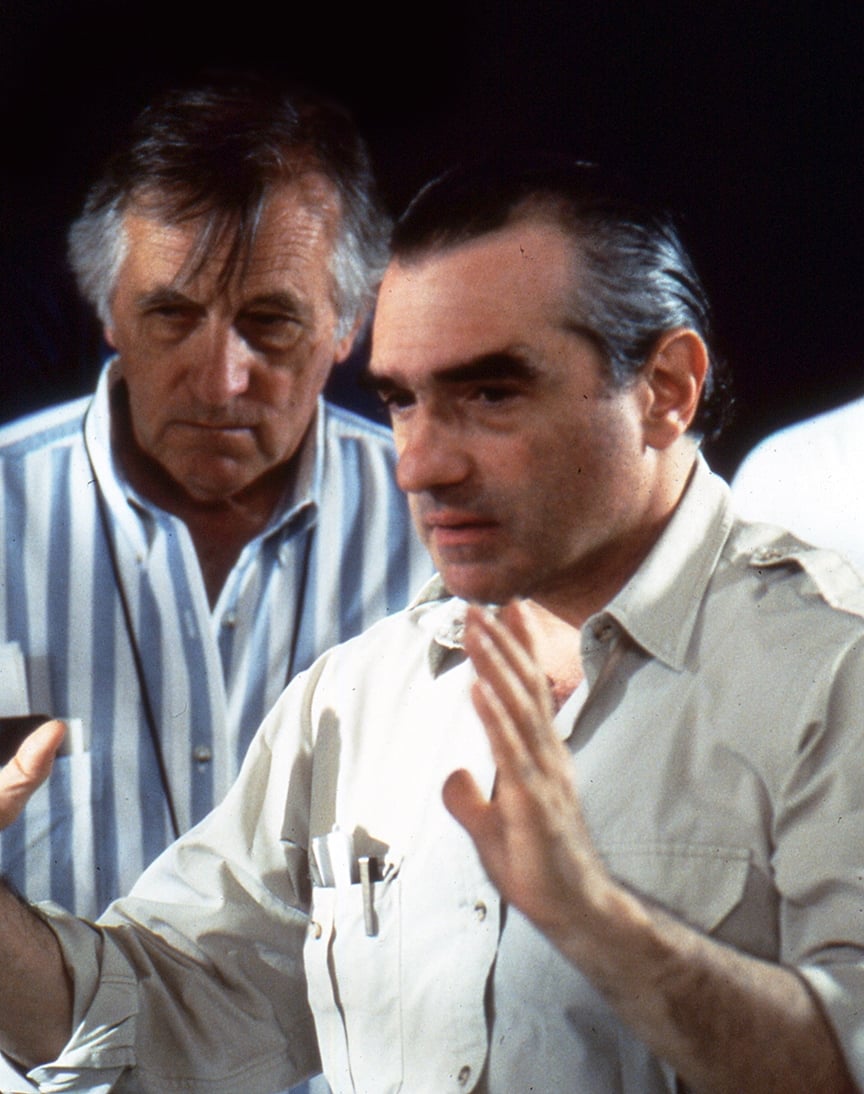

For cinematographer, Scorsese chose Freddie Francis, BSC. “The main thing was Freddie’s understanding of the concept of the Gothic atmosphere,” Scorsese explained. "He knows the atmosphere that I want for this picture. He knows the lighting — whatever it takes to get that incredible, Gothic thriller look. He understands the obligatory scene of a young maiden with a candle walking down a long hall towards a door. 'Don't go in that door!' you yell, and she goes in! Every time she goes in! So I say to him, 'This has to look like The Hall,' and he understands that."

"When we spoke originally about the movie, we were both on the same wavelength. He had the film firmly in his mind before we started, and I knew exactly where he wanted to go with it.”

— Freddie Francis, BSC

Francis was interested in working with Scorsese, but was also drawn to the project by his memories of the original Cape Fear. "Funny enough, though I didn't remember the original picture in detail, thinking back I remembered the mood of it, and as far as I'm concerned a very important part of any picture is if it captures a mood. I don't want to do a film unless I've got a chance to create a mood and an atmosphere, which is what I think my job is," he states. "Anybody can photograph a film — you can just put lights on and make an exposure. I want the challenge of creating an atmosphere and the right frame for the director."

Although Francis recently won his second Academy Award (for Glory), he earned his reputation with black-and-white cinematography, on Room at the Top, Sons and Lovers and, later, The Elephant Man. Scorsese wanted to replicate the stark contrast and murkiness of black-and-white photography, which Francis finds easy to do: "I don't really know anything about color. I still photograph things in black-and-white, but the fact that it's color stock means they come out in color. I know that sounds rather facetious — I am rather facetious anyway — but I prefer to think in terms of light and shade than in color.

"One of the ideas I had for the film," he continues, "was how normal people living in a normal house change, so that the atmosphere of the house changes with them — it degrades as the story goes along. The thing starts off bright and sunny and then slowly gets more downbeat, reaching the lowest depths when we get into the tank for the final sequence. From the beginning, the house was a very light and airy place, but always recognized was the fact that it was hemmed in, as if the trees at any time could dose in on the house like a lot of Triffids."

Francis' reference to 'Triffids" recalls his extensive work for the Hammer and Amicus studios in the '60s and '70s. He directed more than 30 films over the course of 15 years, mostly of the horror genre. Day of the Triffids was a sci-fi thriller where ambulatory plants called Triffids take a stab at ruling the earth.

Francis has always been an advocate of source-true lighting. "As I have always said, before I light a scene, I have to find a reason for it," he states simply. "The light has to come from somewhere." However, this particular film's low lighting conditions have limited him to a certain extent, since the figure of the psychopath Cady is supposed to lurk ambiguously in the shadows. Shooting in Panavision and CinemaScope, Francis has discovered difficulties using currently available 'Scope lenses to film deep-focus on what is essentially a very dark movie.

“The main thing was Freddie’s understanding of the concept of the Gothic atmosphere. He knows the atmosphere that I want for this picture.”

— Martin Scorsese

"Most people forgot about CinemaScope about 10 or 12 years ago, and so we are really working with very old equipment. For the sort of stuff Marty wanted, we had some trouble with the lenses; they have a limited focus range. Panavision has improved CinemaScope lenses just recently — they have one set of new lenses which I gather are very good — but, unfortunately, that's another movie."

Early on, Francis considered using special filters he developed for The Innocents. The filters shade selected areas of the CinemaScope frame, thereby concentrating attention on specific characters. "What it did was make the edges murky so you didn't quite know what was going on just outside the main point of vision, so we could keep the interest up in the center," he relates. "It worked in that instance, but here it's a different thing. There's a family in the middle that’s being terrorized by this man on the outside. This horrible Cady character is so evil, he outwits these people at every turn and they can't get away from him; he's always hovering on the outside. To my mind, that has been the overriding reason we haven't used those filters, though I may still use them in the tank when we do the long shots of the boat: we close in on the boat and the edges are sort of mysterious and dark."

Francis adds, "I always use Eastman Kodak — I’ve never used anything else — and this time I tried the 5248 and 5296.1 find that given the areas and locations we’ve been working in, I’ve had to use the fast stock for about 80 percent of the picture.”

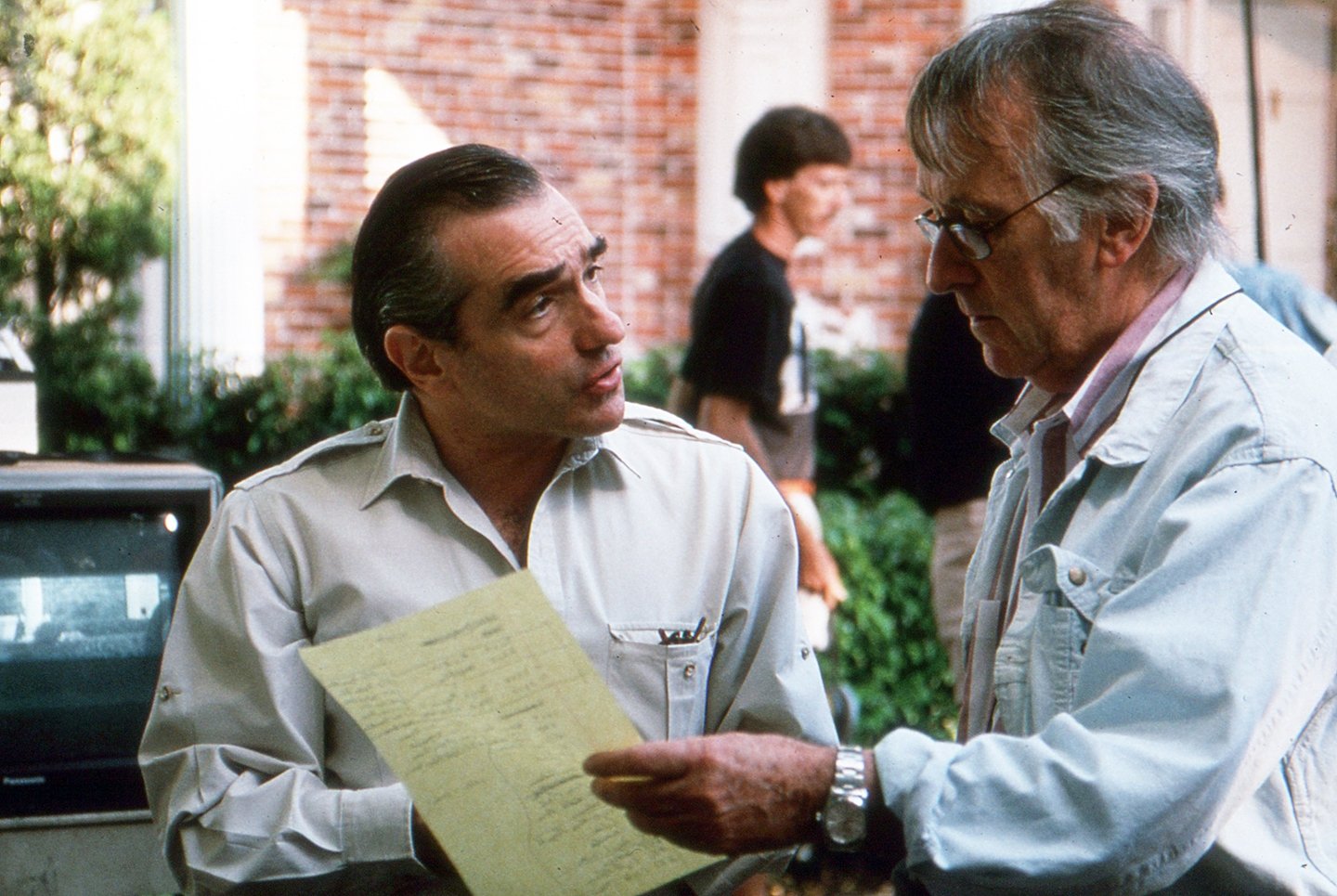

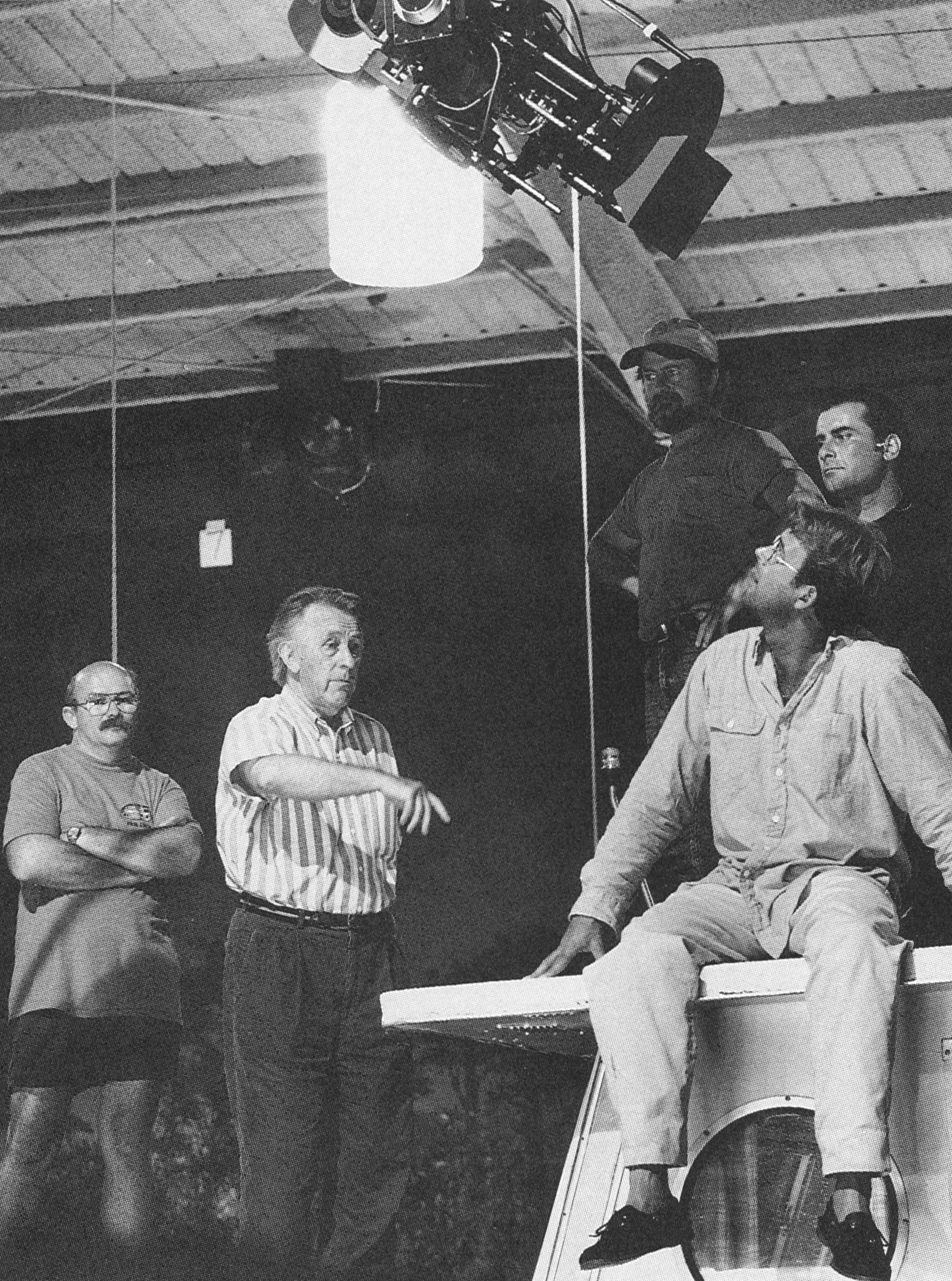

Scorsese admits to allowing Francis enormous freedom, but Francis initially found the lack of detailed communication, and the director's seemingly removed presence on the set, somewhat off-putting. The elaborate storyboarding went a long way toward facilitating their collaboration. “When we spoke originally about the movie, we were both on the same wavelength. He had the film firmly in his mind before we started, and I knew exactly where he wanted to go with it. But as far as the nuts and bolts of shooting are concerned, our methods are very, very different. It's my job to get into the swing of it, though; I don’t expect Marty to change his methods [to suit me].

“Marty hates being on the set outlining a shot; he’d rather talk about it and then stay off until we've done it,” he continues. “It was very disconcerting for me to just sort of discuss an effect with Marty, then have to go on the set and plan roughly what I think he wanted. I have to be right on the floor, right by the camera, to control and speed the thing along. Marty likes to be by the television remote, and this was a bit difficult for me. I can’t operate unless I’m right by the camera. But that's my method, and this is his method.”

Although Scorsese scrupulously plans out the style and speed of each scene, he can be open to improvisation once he arrives on a location with the actors. He also favors extremely kinetic camera moves, which means that Francis had to be prepared for anything. “Particular setups are something that I find very difficult to think of too much in advance, especially with Marty. The camera's swinging all over the place — shooting upward, downward, backward and forward — and it would be mad to think in advance how you're going to do that; you think you're going to do a shot with a set camera, and suddenly you find the camera is rotating about 360 degrees.

“Martin’s a great ‘editing room director.’ I know that we may be doing a shot that runs for about 30 or 40 seconds with a complicated movement, and then he'll pick out about 24 frames, go away in peace with [editor] Thelma Schoonmaker and piece them together.”

Having worked as a director himself, Francis is generally cautious about imposing too many of his own ideas when he serves as a cinematographer. In the case of Cape Fear, however, he feels that he may have undercut his usefulness to Scorsese by not pushing the boundaries of their relationship, “There's was an enormous amount of room for me to play around with, but I didn't know how much to jump in. In the last few weeks, because we got into the tank and some special effects — something Marty’s never been involved with before — I found that I was making far more suggestions than I usually make to directors. So I think we achieved a good working method — but it took a long time!"

Cape Fear is the first widescreen picture directed by Scorsese, whose films are known for their intimate, gritty feel. While working on Fear, he luxuriated in the compositions while simultaneously fretting about the massive array of equipment needed to produce a clear, sharp 'Scope image, even when using handheld cameras. Scorsese was also frustrated that he had to shoot the Bowden house scenes in a real house, since he had hoped to shoot much of the picture on swing sets.

Several sets were built to accommodate shooting, but the majority of scenes were shot on actual locations in the Fort Lauderdale/Miami area. This meant that Francis had to squeeze equipment into some confining interiors, particularly for those scenes where Scorsese shoots with two cameras to cover the reactions of all his actors. "We did one scene of Bob De Niro coming out of prison, where we had a great crane in a small prison area, about 20 or 30 cells on two different levels, and started a long sequence of Bob in the cell; then the camera had to draw back through the bars — we had some collapsing bars — and Bob comes out of the cell and walks all around the prison and goes out.

"There have been problems of falling behind schedule ever since day one," relates Francis. "Obviously the complicated camera movements have something to do with it, but then again this is the style which Marty wanted. So I've said to these production people, 'Look, every day we work we get a little further behind. Why don't we have two or three weeks off, to see if we can catch up?' But they don't think that's very bright!"

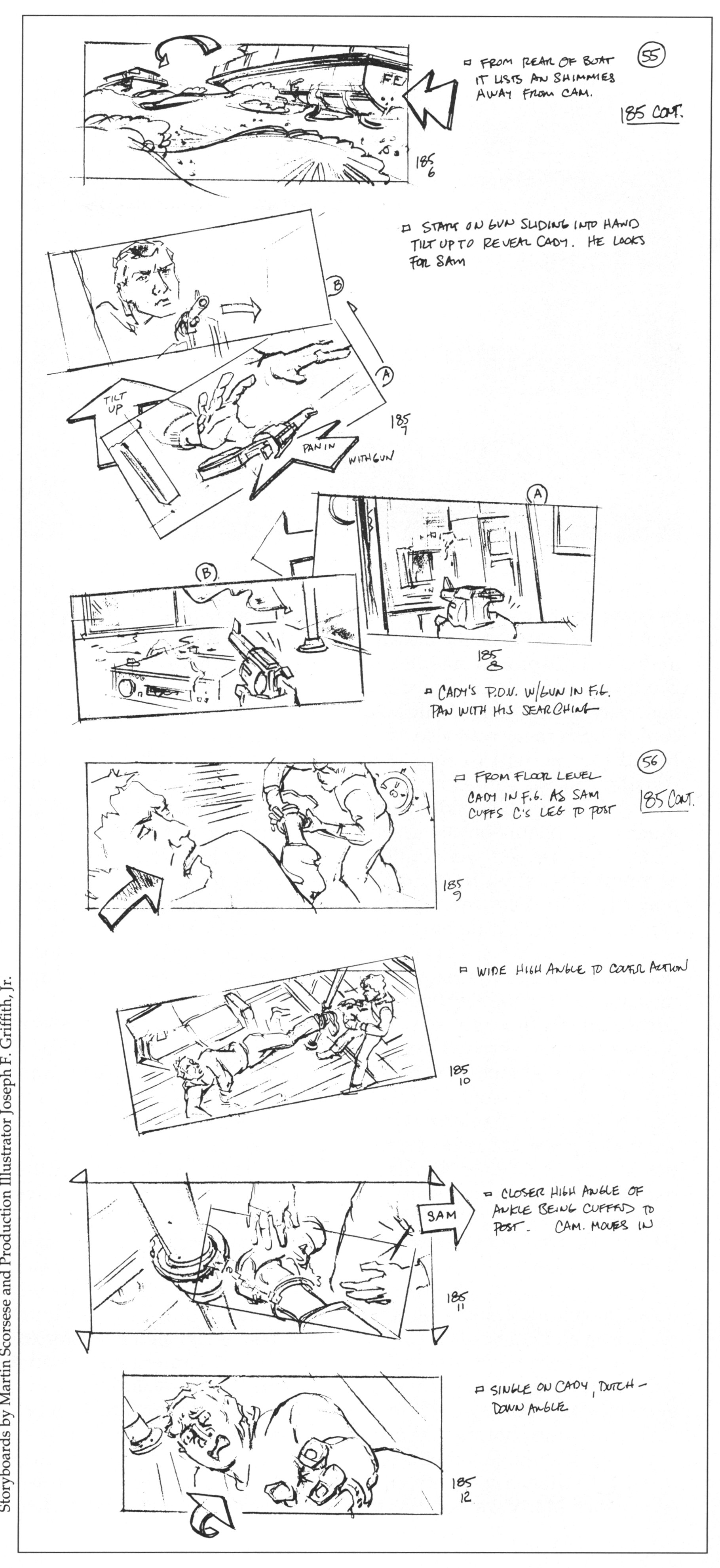

The most technically demanding sequence of Cape Fear is the climactic confrontation between the Bowden family and Cady, which takes place aboard a houseboat on the Cape Fear River, during a violent storm. A 90'-long water tank, housed within a soundstage constructed specially for this production, was equipped with rocking gimbals for a mockup of the boat, as well as rain and wind machines.

Francis, of course, has seen this kind of thing before; in 1956 he photographed the effects and models for Moby Dick. "That was about a hundred years ago," he chuckles.

Though shooting in the Cape Fear tank went several days over schedule, the sequence adheres very closely to the original storyboard sketches. The characters' anxiety at being trapped within the confines of a small houseboat is signaled by distorted and skewed camera angles and movements, and by the intensity of the close-ups. "From those sketches I knew exactly what Marty had in mind, so I worked towards that end. It's difficult to find improvements on sketches; it's easier when you get on the actual location, for these [storyboards! were mere figments of Marty's imagination.

“If you’re storyboarding a sequence, once you start going away from those storyboards, the rest of the storyboards become of no consequence. So Marty sticks to them.”

"Though he's not used to special effects pictures, Marty does adhere to these storyboards. If you're storyboarding a sequence, once you start going away from those storyboards, the rest of the storyboards become of no consequence. So Marty sticks to them. Of course, once you get underway, the physical things sometimes outweigh the storyboards, and you have to adapt."

Francis kept his lighting setup simple. "I had some space lights, which supplied a sort of general, half-a-key light. Then we had rather large light sources with which we were backlighting and three-quarter-lighting the battling actors. For the lightning, we used 12Ks with old-fashioned brute dimmer shutters.

"We made great use of a piece of equipment called the Panatate," he continues. "It's a mount designed for revolving the camera, which we did several times on various shots. But we also used it as what we call a 'sea head,' the kind of mount one would want on a boat to give it the feeling of rocking back and forth. The Panatate worked very well for that — in fact, it was better than the normal sea head. It's very adaptable.

"Marty gets very involved in these things," Francis continues. "I introduced the Panatate to him, and he used it in an unusual way, to produce some very dynamic shots — not just to give the sense of pitching and rolling, but to give the story a dynamic twist now and then.

Francis' adherence to source lighting was tested during the night scenes on the boat. His response was typically pragmatic. "I had to figure out where the light was coming from," he says. "In addition to the lightning, I've got water running all down the windows of the boat, which catches the light. Then one has the additional sense of distant lightning. Much of the fight takes place almost in silhouette. In fact, when De Niro and Nick Nolte are fighting and the boat is breaking up, I persuaded Martin at one point to kill all the lights and conduct this fight in the dark. Well, how does one go about that? How can I make this absolutely pitch black, but so that everybody can see it?

"The light that we put in is what we refer to as 'customer's moonlight,'" he reveals with a smile. "It's just enough light so that the customers who pay to see this film can see what's going on. One keeps it shadowless as much as possible, but with just enough exposure to see what's going on.

"For the storm sequence, we were using Kodak 5296 almost exclusively. I usually rated it anywhere from 400 to 500 ASA, but I find that with modern development, the negative remains the same regardless of the rating. You almost can't underexpose the stuff, unless you try very hard."

In post-production, miniatures of the houseboat were shot in England (under Francis' supervision); for this reason, the ending of the film was the first sequence edited by Scorsese and Schoonmaker. Matte paintings were created by Syd Dutton and Bill Taylor, ASC of Illusion Arts of LA, whom Francis has used in the past. One matte shot comes early in the film, as Cady is released from prison. The painting, suggested by a production painting by Henry Bumstead, extends the foreground of the prison gate (shot at a Southern Florida women's detention facility), and features an ominous, boiling sky in the background. "Illusion Arts presented Marty with several different skies, and asked 'Which sky do you want?"' Francis remembers.

"I think the mood of the picture, regardless of my contribution, is there," Francis concludes. "It's quite frightening, and that to my mind is coming across. That's rewarding because it means we were all going forward in the right direction."

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.