Challengers: An Intense Courtship

Cinematographer Sayombhu Mukdeeprom and director Luca Guadagnino discuss their shotmaking on a romantic drama involving tennis pros.

Unit photography by Niko Tavernese, courtesy of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Pictures.

Luca Guadagnino’s Challengers is framed by a fierce tennis match between Art (Mike Faist) and Patrick (Josh O’Connor), former friends and doubles partners who now find themselves on opposite sides of the net during the Challenger Tour. A mix of flashbacks and contemporary scenes off the court gradually illuminates the men’s shared past, which revolves around their mutual romantic interest in Tashi (Zendaya) — Art’s coach and wife, and the keenest spectator in the stands.

Guadagnino calls the men’s professional faceoff “an über sequence” that had to mirror the growing intensity of the off-court drama, so much so that by the final minutes of the match, “we become the match,” and the camera takes on seemingly impossible perspectives, including shots from beneath the court and the ball’s POV. “The game is super precise,” the director says, “and the arc of the experience of the game for the audience is all part of a huge building toward what it sees at the end.”

Dynamic Perspectives

The climactic tennis sequence called for about 90 setups and includes 500 cuts, and its length and technical complexity motivated Guadagnino to storyboard it, a process he seldom uses. “I drew basically the entire sports sequence, so for the first time in my career, half the film was storyboarded,” he says.

Cinematographer Sayombhu Mukdeeprom acknowledges that this strategy was a necessary departure from the method he and Guadagnino have used on such films as Call Me by Your Name and 2018’s Suspiria (AC Dec. ’18). “Storyboarding was not common, but I think we needed it in this case because there were certain movements with the ball and players and specific positions that needed to be clarified,” Mukdeeprom says.

Storyboarding also facilitated the integration of visual effects, which Guadagnino says was necessary to achieve “some of the more daring sequences, particularly the subjective point of view of the ball.”

According to camera operator Terrence Hayes, “The storyboards were vital and gave us an insight into what Luca wanted to convey emotionally. These complex action shots took a team effort, and they wouldn’t have been possible without the efforts of dolly grip Chris ‘Chappy’ Chapman, head tech Dan Sheats and 1st ACs Jamie Fitzpatrick and Tim Sweeney.”

Embodying the ball’s POV as it careens across the court and over the net lends the image a riveting velocity that couldn’t be achieved practically. “We can’t move the camera that fast, but [with visual effects] we can completely control the path of the ball in the direction we need,” says Mukdeeprom. “We shot a bit wider, which gave us the ability to reframe and crop out any bad movement, etc.”

One of the most remarkable perspectives during the Challenger match places the camera beneath the court as the actors run across it. Mukdeeprom calls the solution — a large, floating, clear acrylic platform — “so simple,” noting, “The court had to be strong enough for the actors to run on it, and high enough for the camera to go underneath.”

Golden Hours

To help with lighting continuity, the cinematographer also wanted each set in the Challenger match to be filmed at a certain time of day. “For this scenario, we needed a storyboard,” he says, “and it was really helpful.”

The mandate meant confining the shoot to a few hours each day, however. “For the final sequence — the last 10 minutes of the match — we could do no more than two to four hours a day,” he recalls. “I would say it involved a total of 35 hours of shooting spread over eight days.”

This section, the third set of the match, “falls into the golden-hours light,” Mukdeeprom says, noting that due to the movie’s flashback structure, the match starts amid the third set before flashbacks take the audience to the first set and other moments in the characters’ past before they return to the climax of the match. So, as Guadagnino notes, “The movie is really framed by this golden light that is going through the beginning [of the movie] to the end.”

To supplement the natural light, Mukdeeprom positioned two 100K SoftSuns on one side of the court.

Establishing the Characters

Art and Patrick are introduced to us as two seasoned pros who appear to be at vastly different points in their careers: Art is a high-achieving star weathering a losing streak as he recovers from an injury, and Patrick is barely scraping through minor tournaments.

It was crucial to establish a camera language that emphasized the characters’ differences — one clean-cut, the other a slob; one rich, the other broke; one a nice guy, the other a bit of a scamp.

The solution was maintaining a distance, a style that comes naturally to Mukdeeprom, whose work is often defined by patient, observational medium shots and wides. Guadagnino explains, “I needed to see them from far away so I could show the difference and the distance between the two of them … and, basically, the glue that is going to bring them together, which is Tashi. So, we see them [in] wide shots of the game at the beginning; [then] we go behind the umpire, and we walk and go straight to her. Then we know that these two [men] are meant to be there because of [her].”

The shot he refers to is a dramatic reveal of Tashi, who’s seated at center court, an active participant in the drama even though she’s not playing the game. “The camera goes across the court and surpasses the shoulder of the umpire — it goes from high to low in the middle of the court while the balls are going [back and forth],” the director explains. “It’s an impossible point of view, so we used a dolly track with a zoom, along with CGI.”

Mukdeeprom notes that the sequence had to be broken up into pieces. “We separated the shot into sections, filmed those sections one at a time, and then CGI did its job. In reality, the positions of the actors, the width of the court, the length of the move [were things] we needed, and things that were in the way of the move were limitations. If we wanted to go beyond that, we needed help from CGI.”

Guadagnino says he prefers using visual effects to create the illusion of reality rather than more fantastical visual elements. “I’m not very into CGI for creating the illusion of weightlessness; I prefer to feel the weight of things.”

Tried-and-True Technologies

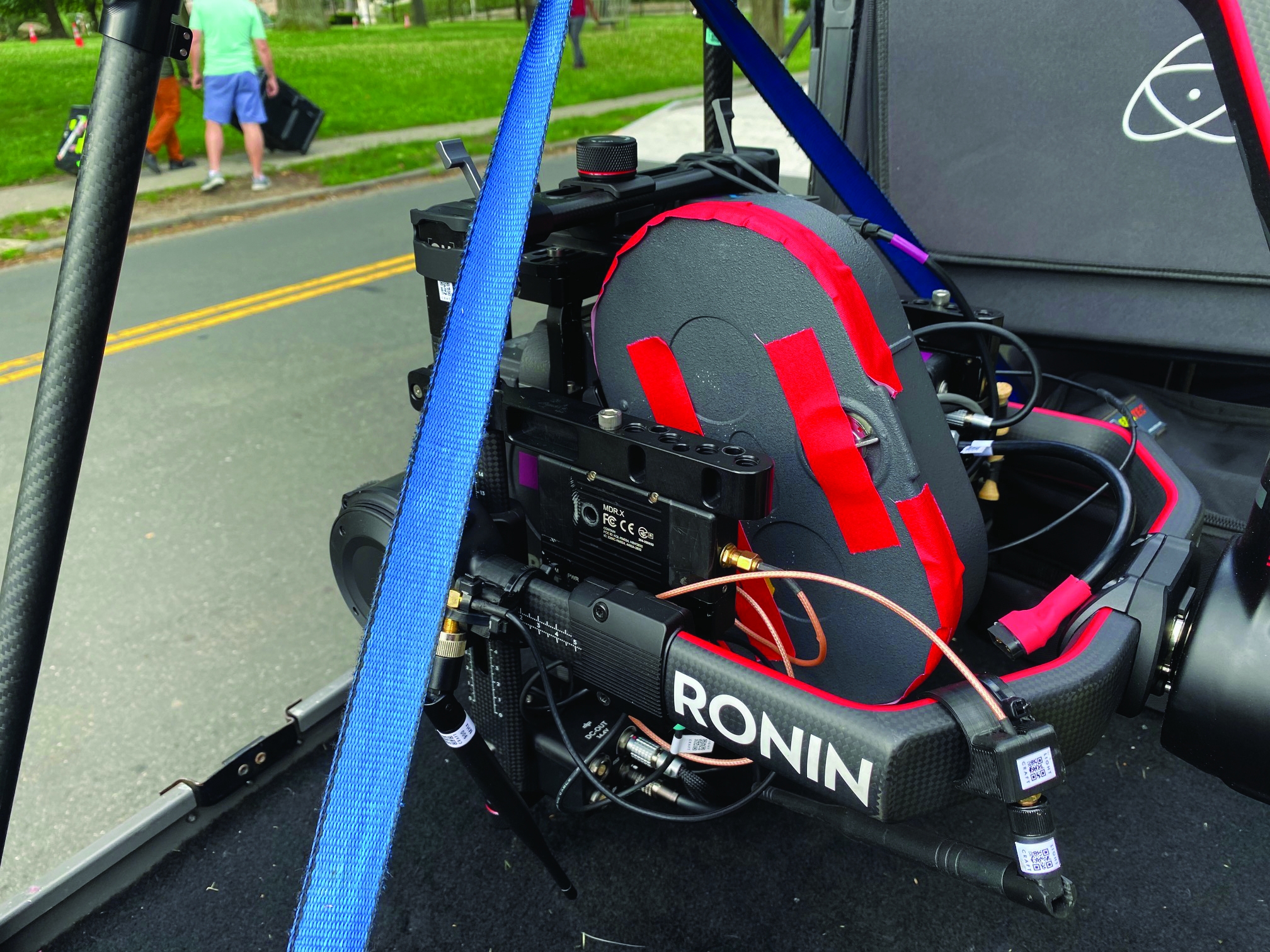

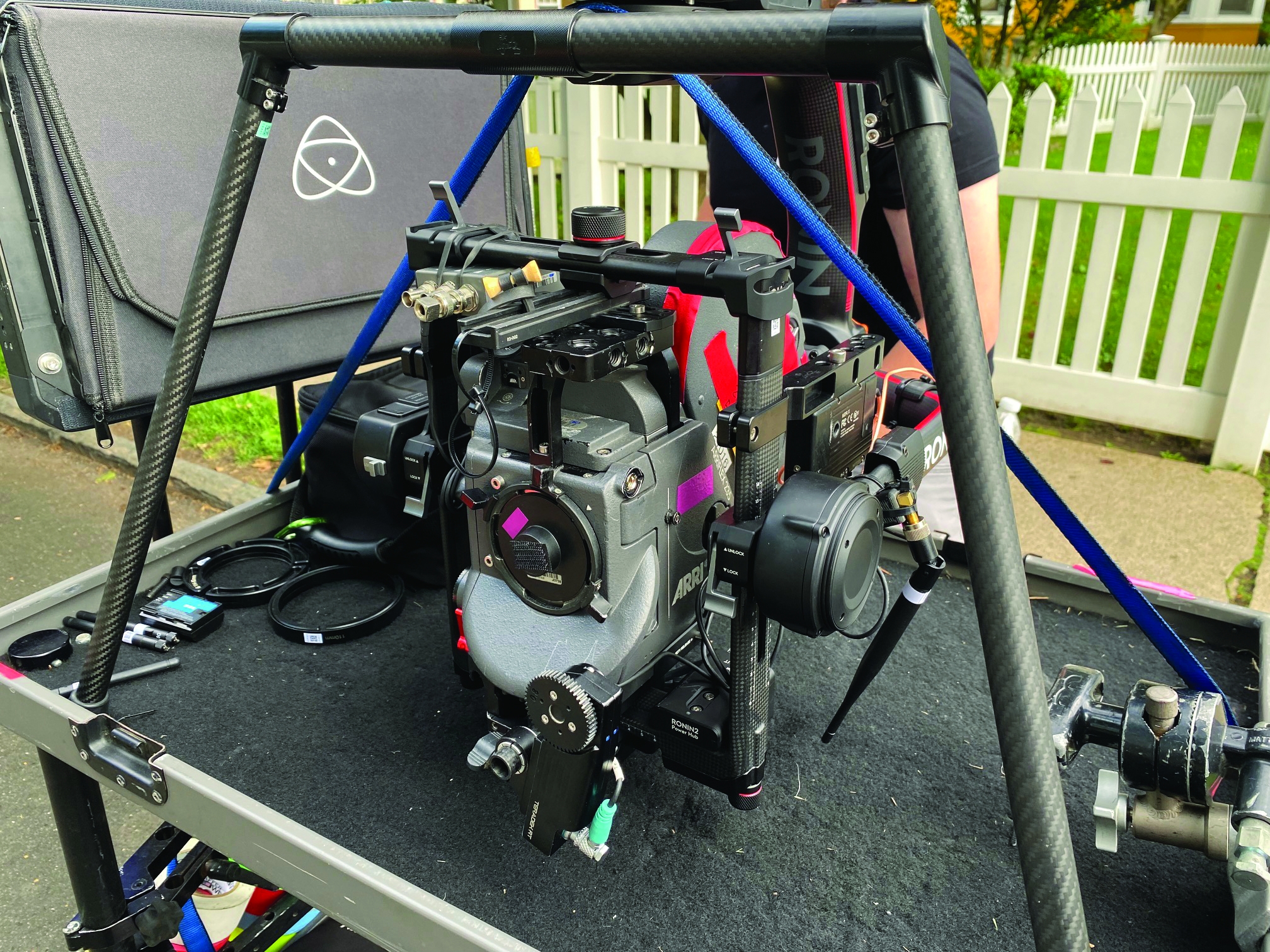

Mukdeeprom, who favors shooting film, photographed Challengers with Arricam ST and LT cameras in 3-perf 35mm on Kodak’s Vision3 500T 5219. He notes that he tends to stick with technology that’s familiar. “The Arricams are very well designed, robust and reliable,” he says.

Mukdeeprom usually had the camera on a dolly whether it was stationary or moving. He avoided Steadicam for the tennis action, instead deploying a Scorpio 45 crane with a Libra head. “It was better because we could do a tilt, which a Steadicam doesn’t do as well,” he observes.

During matches, the camera frequently flies from a spectator in the crowd back to the court, pushes over the net, or flies up to take a bird’s-eye view of the action. The sweeping shots facilitated by the crane help accentuate both the tension of the game and the tension of the personal relationships.

The cinematic camera language in Challengers is distinctly different from the conventional presentation of tennis on television broadcasts, which can employ a minimum of six cameras to ensure total representation of a match. Instead, Julian Collazo Bass, who served as a camera assistant on a portion of the shoot that took place at Arthur Ashe Stadium in Queens, N.Y., helped to plan a three-camera setup that was often implemented to film the gameplay sequences, with one camera on the crane and the other two covering the players on either side of the court. Doubles were used for the actors during complicated tennis action, capturing them in wide shots before moving in for close-ups of the primary actors.

Getting Inside the Game

Guadagnino says that it was while watching the actors’ doubles repeat action on the court over and over that he began to understand how to “get inside” the game of tennis. “I started to understand the game, what it meant, and how it was also the game of love, the game of sex and the game of tension within the characters.”

When the action moves off the court, the tension of the characters’ rivalry intensifies. A pivotal scene between Tashi and Patrick takes place in a windy parking lot at night. Though no wind was called for in the script, Guadagnino conceived a huge storm barreling through the region for the Challenger finale. “I thought that for these three people, it could be another beautiful way of creating a visual metaphor for what they are going through,” he says.

As Tashi and Patrick are whipped by the wind, the scene is suffused with blinking light, and the characters’ movements grind into slow motion.

Guadagnino describes how the scene evolved: “We shot that on the outskirts of Boston, and Sayombhu had this great idea of making the car’s red brake lights a protagonist in the scene to heighten the tension between the two characters.”

The filmmakers also sought to lend the sequence a kind of “strobing” effect that would blur the characters’ movements. The director adds, “Then I thought to myself that the motion of the wind and the dynamic of the characters moving away from each other, going toward each other [and] spitting at each other would be stronger if we ‘froze’ them. That’s when I decided to shoot everything in hyper-slow motion.”

Mukdeeprom says the filmmakers tried this, but shooting at very slow speed (with a Photo-Sonics high-speed camera) made the resulting action too slow to create the desired effect. In the end, they shot the sequence at various speeds to give the production’s visual-effects team enough footage and information to create the effect in post.

During editing, Guadagnino slowed the motion down even further, almost to freeze frames. “I wanted to have an almost impossible eroticism happening between the two. They play cat and mouse in the car; they clearly want to do something together that is erotic; and they can’t, because they’re fighting and can’t admit [their feelings for each other]. But then they surrender to [the moment]. In order to see that moment, we made it very slow.

“I love cinema and I love to use the tools,” he adds, “but I always think first in emotional terms.”

TECH SPECS

1.85:1

Cameras | Arricam ST, LT; Photo-Sonics (for high-speed work)

Lenses | Arriflex/Zeiss Standard Speed; Gecko-Cam Stealth Zeiss HS (rehoused Arriflex/Zeiss Super Speed); Angénieux Optimo zoom; Arri/Zeiss Ultra Prime; Canon telephoto; Century Series 2000 zoom; Arri Macro

Film Negative | Kodak Vision3 500T 5219

Spotlight on Optics | Vintage Imaging

In choosing lenses for Challengers, Mukdeeprom turned to some old favorites. “The Arriflex/Zeiss Standard Speed T2.1 and Arriflex/Zeiss Super Speed T1.3 are always our main lenses simply because I am so familiar with them,” he says. “They’re small and fast enough to give me the ability to deal with the lighting style we love to create.”

The tennis matches were captured with a combination of zooms and primes. “I feel like a lot of what Luca shoots is kind of voyeuristic,” says camera assistant Julian Collazo Bass, recalling the way flashbacks of Tashi, Art and Patrick competing in a juniors tournament were filmed. “Obviously, we’re watching a match, so we’re watching players and we’re in the stands, and it’s a lot of over-the-shoulder and tight shots that show the match happening, so we really used a mix of primes, primes with some extenders, and zooms.”

Mukdeeprom says the wide lenses were the workhorses for tennis action, and that the Super Speeds were particularly good for capturing the actors’ reactions after an action shot.

The Super Speeds used on the production were rehoused by Gecko-Cam in Germany, and are known as the Stealth Zeiss HS series. These lenses included an 18mm, 25mm, 35mm, 50mm, 65mm and 85mm. “They’re rehoused vintage lenses and they’re beautiful,” Bass says. “You’re zoomed in on the match from the stands and then you turn it around, and then you’re on their faces watching their reactions. The imagery is beautiful. The vintage lenses pair really well with the classic game of tennis.”

Mukdeeprom captured a lot of the Challenger match with the show’s Scorpio 45/Libra head pairing and an Angénieux Optimo zoom. “The Optimo 24-290mm is another workhorse,” he says. “Combining a zoom with the crane arm extend/retract was particularly useful on the court.”

— Sarah Fensom

The cinematographer later sat down for this episode of ASC Clubhouse Conversations: