Children of Men: Humanity’s Last Hope

Emmanuel Lubezki, ASC, AMC devises a naturalistic approach to depict a grim future in this sci-fi drama.

Unit photography by Jaap Buitendijk

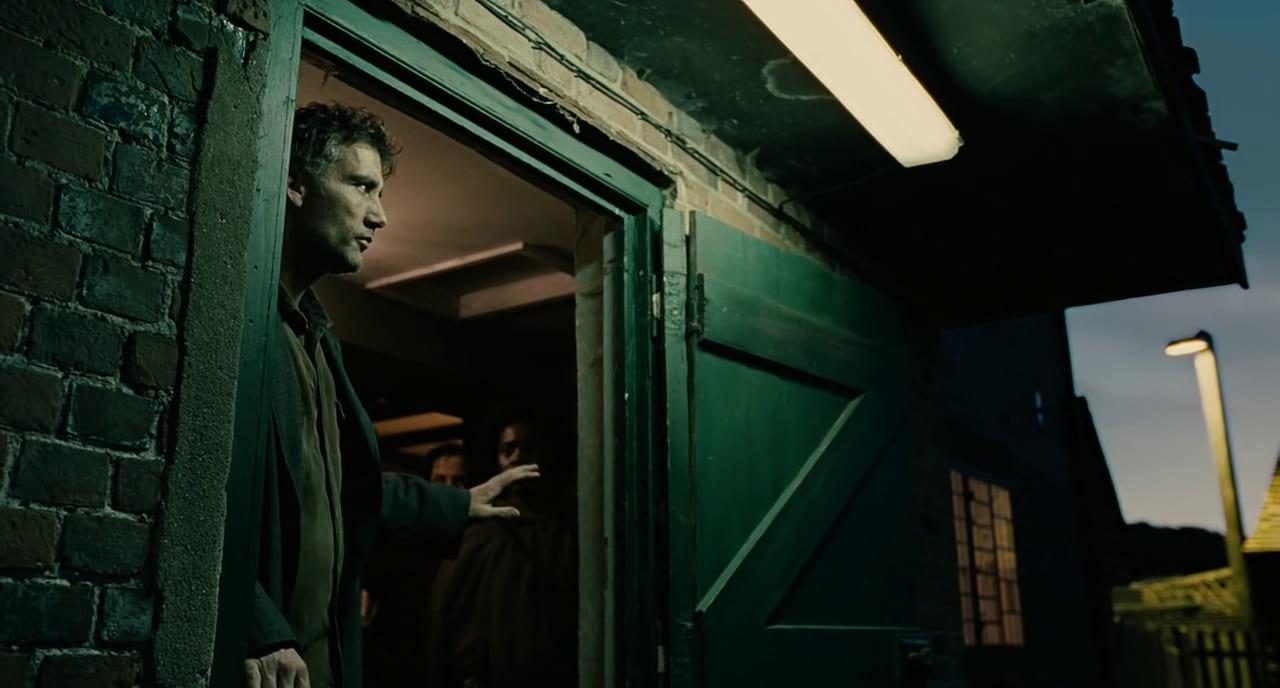

Emmanuel Lubezki, ASC, AMC stands in the street and anxiously scans the clouds above. He needs the sun for the next scene. We are visiting the set of Children of Men on a day when the production has set up in an industrial section of London. A doubledecker bus rolls up into position, its windows covered with grating that gives it a penal quality. Thirty extras dressed in drab clothing are lining up, ready to board and provide background action. The story takes place in the near future, and nothing feels radically different until a strange motorbike with a passenger platform pulls up alongside the bus. Big green panels on the sides of nearby buildings indicate where huge video images are going to be inserted during post.

Director Alfonso Cuarón starts a run-through of the action. Gaffer John “Biggles” Higgins squints at the sky through a neutral density monocle to calculate the sun’s path for the next half-hour. Camera operator George Richmond is handholding an Arricam Lite, framing the open bus door, while his brother, Jonathan “Chunky” Richmond, is riding focus using a wireless control. The bus starts its motor, and actor Clive Owen runs alongside the double-decker and jumps on. The camera swings over as Owen sits next to an elderly woman passenger. After the rehearsal, Lubezki quietly confers with Higgins. They decide to bring up the dim interior of the dirty vehicle by setting up some lights to bounce off beadboard outside the bus. The lights are in position in five minutes flat. After some more tweaking, Cuarón is ready to roll film. Just before the first take, Lubezki turns off the lights, and the entire scene is shot without any film lighting.

In the dailies the next day, the bus scene looks great. The image is gutsy; you can distinguish the bright exterior, and the bus interior is dark, but it brightens momentarily as the vehicle goes past a large, sunlit façade. Lubezki reviews his decisions of the day before. “When you’re not using lighting, everyone on the set needs to be conscious that if you lose the sun, that’s it.” The fill from the sunlit building, he continues, is “the kind of accident you get when you don’t light. However, accidents aren’t always good.”

“It took me a long time to go back to basics and say, ‘No, I don’t want this movie to look conventionally beautiful.’”

— Emmanuel Lubezki, ASC, AMC

Asked about the unused light on the bus ceiling, Lubezki says, “Sometimes you panic because you’re used to doing things in a certain way. I’m a feature-film cinematographer, and I haven’t done documentaries in a while, so my instincts are to always try to make the image appealing. It took me a long time to go back to basics and say, ‘No, I don’t want this movie to look conventionally beautiful.’ This is a movie I couldn’t have done when I was younger. I don’t know if I’m going on the right path. The more I learn, the less lighting I want to do.” With a chuckle, he adds, “Maybe I’m getting lazy!”

Lubezki’s résumé suggests otherwise. His recent credits include Ali (see AC Nov. ’01), Lemony Snicket’s A Series of Unfortunate Events (AC Dec. ’04) and The Assassination of Richard Nixon, and last year he earned his third Academy Award nomination, for Terrence Malick’s The New World (AC Jan. ’06); he was previously nominated for Sleepy Hollow (also an ASC Award nominee; AC Dec. ’99) and A Little Princess (another ASC nominee). Children of Men is Lubezki’s fifth feature-film collaboration with Cuarón, following Love in the Time of Hysteria, A Little Princess, Great Expectations, and Y Tu Mamá También.

Children of Men, an adaptation of a science-fiction novel by P. D. James, takes place in England in the year 2027. For unknown reasons, women have stopped having babies, and as the human race contemplates its own extinction, society begins to crumble, and a dictatorial government is threatened by a group of rebels. The protagonist is Theodore Faron (Clive Owen), a bureaucrat who is approached by an ex-girlfriend, Julian (Julianne Moore), who is leading an underground movement that is fighting the authorities. At Julian’s request, Faron reluctantly agrees to help two fugitive women move across checkpoints and borders to the seashore, where they are to flee the country. He soon learns that one of the women is pregnant and that her companion is a midwife. The treacherous voyage leads to dangerous encounters with police and rebels, and Faron dedicates himself to safeguarding the first baby in a generation.

Laced with themes of ecological disaster, media saturation and terrorism, Children of Men has a timely message that surpasses its entertainment value. “More than the specific plot of the movie, what I like is that it’s a future that reminds you of the present,” says Lubezki. “It’s a political film that says we have to save the world right now, before it’s too late.

“I didn’t want to light the movie, or at least I didn’t want it to feel lit. I want the viewer to feel as though the action is happening for real.”

agreeing to help

a group of

underground

resistance

fighters, Theo

safeguards Kee

(Claire-Hope

Ashitey), a young

woman with a

dangerous

secret.

Shot entirely handheld with very little traditional film lighting, Children of Men has a visual aesthetic that borders on documentary. Lubezki recalls that the genesis of this look started with a decision to avoid standard shot breakdowns. He explains that he and Cuarón have an aversion to traditional coverage, with “A-B-A-B” intercutting of opposing shots of two actors. “We decided to have every shot be a shot in itself and avoid the A-B-A-B of coverage, even though we couldn’t get away from doing it sometimes. The more I work this way, the more I realize that conventional coverage is what makes most movies feel the same. You go to see a comedy, a drama, or a horror movie, and they all somehow feel the same. It’s as if the cinematic language hasn’t really evolved that much. Many films just cover the dialogue without really exploring the visual dimension.”

To avoid intercutting, much of Children of Men was shot in lengthy single takes, which were shortened in editing “either for rhythm or dramatic intent. We did the movie in long shots to try to get the audience to feel they are there.”

One of the key decisions Lubezki made early on was to shoot Children of Men with as few movie lights as possible. “I didn’t want to light the movie, or at least I didn’t want it to feel lit. I want the viewer to feel as though the action is happening for real. I didn’t want to make anything pretty or beautiful unnecessarily. For example, I didn’t want to put a backlight on an actor [for beauty reasons]. Of course, I couldn’t get away with not lighting at all. When winter came, the locations we were using between buildings started getting dark very early, so some of our locations had to be built on a soundstage. I had to light them, but I did it in such a way that the light was always coming from a natural source, usually through windows.”

He used the same approach for the film’s climactic birth scene, which he lit with a single bulb (mimicking a gas lantern) to achieve a minimum exposure of T2. A scene in a pothead’s abode was lit simply with a “gigantic China ball” above the actors on the couch, along with a background awash in a greenish light used by marijuana growers to nurture their crops.

When a location or set required lighting, Lubezki tried to incorporate the lighting fixtures in the set. For example, the ceiling of a police bus terminal was filled with a grid of Nine-light Mini-Brutes, yielding convincingly oppressive toplight.“We didn’t use them as film lights, but more the way the police would do it,” he says. Similarly, for a night exterior of the fortified police center, he used a series of open-face metal-halide lights.“These lights are used by the army in England. It’s also the kind of work light used by workmen repairing roads at night. We simply stripped them out of their bases.”

Lubezki also used sodium-vapor light, as when Julian confronts Faron, interrogation-style, in a dark interior with an open-face light beside her. The cinematographer adds that the violence of this lighting was heightened by a camera shutter setting that was slightly out of sync, creating a subtle, slow flicker. Lubezki asked the sound designer to underline the effect by adding a variable humming sound. “Then they turn the light off, and there’s a little moment of darkness, and you don’t know what’s going to happen next.” The cinematographer punctuated several scenes with these disturbing darknesses.

When the time came to film the young woman revealing her pregnancy to Faron, Lubezki hesitated about the type of lighting to use. The scene takes place in a manger, and his research indicated that such settings have “two types of lighting: fluorescents or big tungsten lights. At first, I thought the lighting should be warm, but then I decided it should be industrial.” As elsewhere, he heightened the green coming from fluorescents because “green is a color that makes you a little uncomfortable.” He supplemented fluorescents with a beautiful soft source on the woman’s pregnant belly, because given the subject matter, he “just had to.

Lubezki filmed Children of Men on Kodak Vision2 Expression 500T 5229 because its low contrast allowed him to shoot in extreme situations without additional lighting. “When I did tests in the car, the interior was f2 and the outside was f16! Because I had decided not to light, using this stock was a way to solve the exposure problem. It’s so low-contrast that if you expose it correctly, you will have enough information to show what’s happening outside. Of course, in some scenes, you will never be able to see the clouds because the sky is blown out. With [Kodak Vision2 500T] 5218, when you don’t light faces they look a bit harsh. I wanted the mid-tones to be softer in the faces, and 5229 allows you to achieve that. It’s very similar to flashing the positive.” He adds, “The blacks in 5229 are not very rich, but you can crush them in the digital intermediate [DI].”

The cinematographer did not want the production to screen low-contrast dailies with washed-out blacks, so in consultation with Beverly Wood, vice president of technical engineering at Deluxe Hollywood, and Ian Robinson and Clive Noakes at Deluxe London, he had the 35mm dailies treated with a 30-percent application of Deluxe’s proprietary ACE silver-retention process. This gave the filmmakers a better idea of the picture’s final look. “The mid-tones and highlights were not too contrasty, but the blacks remained black because we left some silver,” says Lubezki. “You can never duplicate silver-retention processes exactly in a DI, but you can get close to the kind of contrast and curves they give.” For the DI, he worked with colorist Steve Scott at EFilm to desaturate the images. “We didn’t want the full Kodak-color look; we wanted something more naturalistic.”

Even with a low-contrast stock, one of the biggest challenges on Children of Men was shooting lengthy scenes that take place in a car, as the protagonist's journey to the coast. “Most of the car scenes aren’t lit, and I love all the accidents you get when you don’t light — sunlight coming through a canopy of trees, hitting the actors and bouncing around in the car … is an effect that comes as suddenly as it disappears. I love that all these variations happen naturally. It would take you hours to re-create that with lighting.”

Lubezki’s minimalist approach even extended to wardrobe choices. “I learned on Tu Mamá and The New World that you get a more natural image if you let the wardrobe department do their work without trying to control it, like having everybody dress darker. I didn’t want to impose the cinematographer’s concept of what’s right and wrong, and this really surprised them. They would say, ‘Are you sure, Chivo? Because a lot of cinematographers …’ and I would say, ‘If it’s right for the character, I’m not going to tell you if I like it or not.’ The only mistake I made in this regard was in a car scene, where the midwife is wearing a very bright, tan outfit and is sitting where there is the most light. But you have to let these mistakes go in the interest of realism. It’s like putting on an 85 filter — everything looks better but the image isn’t as complex.”

“One of the reasons I couldn’t operate is that I was constantly changing the f-stop. That was the scariest part about the shoot.”

Lubezki notes that not relying on lighting units encourages problem-solving on location. He gives the example of the encounter between Faron and the midwife in an abandoned, run-down classroom with bay windows. Despite the bright sunlight outdoors, the day interior did not have enough fill light. Lubezki’s solution was to cover one of the big windows with transparent tape and shatter its glass; the fractured pane provides a bright source of diffuse light.

The vagaries of natural lighting mandated constant attention to exposure. “One of the reasons I couldn’t operate is that I was constantly changing the f-stop,” says the cinematographer. “That was the scariest part about the shoot. As Clive enters the classroom, he’s at f2. As we reveal the room, we’re almost at f4, and as he walks in toward the window, we go to f11. When we go to her, it’s f5.6.”

Lubezki’s desire for naturalism sometimes necessitated modifying the story. For example, the scene in which Faron and his crew escape from a rebel farm was originally written as a night scene. “Once they left the farm and went down a country road, it was going to be really awful — I would have had to put up some horrible, fake-looking lights,” he says. “When I read a script that says two lovers are holding hands on a beach at night, as a cinematographer I know it’s going to look fake. For some movies, that fake, over-stylized look is beautiful, but in this movie, it would have betrayed everything we had done before. So I pleaded for another approach to the scene.” It is a testimony to Lubezki’s relationship with Cuarón that the director agreed to change the script, and set the action at dawn. The cinematographer worked with 1st AD Terry Needham to change the shooting schedule so that the scene could be shot dusk for dawn over three evenings.

The result is a sequence that starts in the dark farm, which is lit with fluorescents and sodium-vapor lights, and ends, after a series of dawn-like transitions, with a daytime shot. The gradation from dawn to daybreak is masterful and, Lubezki confesses, partly accidental. “I started shooting the last shot early to get everyone concentrated, and later we shot it at dusk. But the best scene was the one I shot in daytime. So I timed the whole scene to get lighter, so that we could end up in daytime. You think differently when you have a DI. It was brilliant, but a brilliant accident. It’s one of my favorite scenes in the movie.

“The wonderful thing about Terry [Needham] is that he has a lot of experience as a 1st AD on very complicated movies, like Full Metal Jacket and Black Hawk Down,” adds Lubezki. “I was very fortunate to work with him on this project.”

The search for naturalism extended to composition as well as lighting, and the filmmakers made a conscious effort to avoid careful framing.“We were trying not to do a perfect frame, so it doesn’t look framed. We tried to shoot it so that you feel the character more than the filmmaker. It looks like you are there; the image is very objective. You don’t see our tracks.”

Much of Children of Men was shot with an Arri Lite, and the production was among the first to use the new Arri/Zeiss Master Prime lenses.“I think these lenses have a bit of two worlds — they’re sharp, crisp and clean, but they also have flare,” notes Lubezki.“They kept the blacks black but also allowed halation to happen.” His only criticism is that the lenses were sometimes too heavy, and he confesses that he always carried an “extra Zeiss Ultra Prime” for occasions when weight was an issue.

“There’s a lot of violence in the film, and I don’t know why, but violence looks beautiful on film. Destruction and the attendant texture and smoke all photographs well. Violence is very cinematic, and I didn’t want this movie to beautify or glorify it.”

The filmmakers tried to create an objective camera viewpoint by shooting with a wide-angle lens at some distance from the actors. “We shot most of the movie with an 18mm lens; we have no POV shots; we watch the actors from a distance, and there are almost no close-ups. There are exceptions to everything I say, but the main idea was to stay objective, and not too close to the actors. I see an incredible abuse of close-ups in many films these days. Why is that? I don’t know whether it’s due to directors being accustomed to watching things on TV, or because they’re watching the video assist on a small monitor, but they want to get closer and closer. Some movies are all medium shots and close-ups and what they call the master shot. Maybe our ideas for this movie came as a reaction to some of the stuff that bothers us in the current cinema.

Lubezki explains that one motivation for naturalism was to convey the violence in the story properly.“There’s a lot of violence in the film, and I don’t know why, but violence looks beautiful on film. Destruction and the attendant texture and smoke all photographs well. Violence is very cinematic, and I didn’t want this movie to beautify or glorify it.”

To deglamorize the violence, Lubezki took his cue from documentaries. “When you’re watching the news or a documentary on war, one of the things you notice is that there is no coverage. It’s not all cutty with beautiful close-ups of the gun, or the trigger in slow motion. The other thing you notice in many good war documentaries is that the cameraman is often running with a fixed lens — running to cover the action and also running to save his life. So we tried to avoid cutting and beautiful framing. Somehow shooting handheld and not cutting makes violence not only less appealing, but stronger. It looks more naturalistic and you feel more for the characters, as opposed to falling in love with the horrible beauty of war.”

Lubezki says he and Cuarón had two major disagreements on their approach to the picture. The first had to do with Steadicam. “In my mind, I wanted to do a combination of handheld and Steadicam, because I think if you shoot everything handheld [the technique] loses its power. In my dream, Children of Men was going to be 60 percent Steadicam; with a good operator, it doesn’t look mechanical. But on the first day of shooting, we did five takes with the Steadicam, and then Cuarón said, ‘Take away the Steadicam, we’ll do it handheld.’ After that, the Steadicam stayed in the truck, and every day I tried to put it up, until one-day Cuarón said, ‘Chivo, forget the Steadicam. We’re never going to use it.’ One of the things I don’t like about handheld is that when you’re trying to concentrate on a person’s face in a wide shot, you lose definition because there’s motion blur. It drives me crazy, because I want to be able to focus on the actor’s eyes.

The other disagreement between the director and cinematographer had to do with staging the handheld camera. It is customary to have camera movement motivated by the actors, but in Children of Men, the handheld camera sometimes creates its own path, independent of the actors’ movements. “Alfonso and I started doing that on Tu Mamá,” Lubezki notes.

In one scene in Children of Men, there is a confrontation when two cops stop the fugitives’ car. The camera follows Faron as he steps out of the vehicle. When the cops are gunned down and Faron runs back to the car, the camera stays behind to film the car speeding away, and then pans to linger on the two dead cops. Lubezki comments that the camera is almost another character, a persona who is “introducing the energy of the filmmaker, telling you what is important and what we should be looking at. The camera is telling you that these two cops are also parents, or fascists, or whatever. The camera is inviting you to see something external to the plot and saying that it is also important. The camera is inviting you to see the context in another way. I like that a lot.

The staging of handheld camera motion was the subject of much discussion between Lubezki and Cuarón.“When the camera moves in on an actor who is sitting, it distracts me,” says the cinematographer. “I didn’t want to feel the camera’s presence, but Cuarón said that on the contrary, we should feel the cameraman, almost like in a documentary. Sometimes the camera operator had difficulty doing a shot, because it’s counterintuitive to start moving the camera when the actor is not moving, or to let the actor move out of frame. I still had in my mind a more naturalistic approach, which is that once you cannot follow the actors anymore, the take is over. But Cuarón took this idea of the handheld to the extreme and made it very complex. That’s something we still debate.”

One of the most memorable scenes in the film is an uninterrupted six-minute shot inside a futuristic car. Five characters, including Faron and Julian, have a playful moment together and suddenly come under brutal attack by a gang of marauders; the car escapes with one dead passenger, only to be stopped by two cops, resulting in the ensuing gunplay discussed above. In this tour de force one-shot sequence, the camera moves fluidly across the car from front to rear and left to right, easily placing itself between the characters.

The secret to this extraordinary scene was a camera car outfitted with The Two-Axis Dolly, a special rig designed and built by inventor Gary Thieltges of Doggicam Systems. Three carbon-fiber track sections formed an H-shaped rig that was suspended above the roofless car. The Two-Axis dolly moved an Arri 235 on a Sparrow Head back and forth along the horizontal track, which was itself moved fore and aft along the two supporting parallel tracks. The camera was suspended from the dolly into the car below and controlled by Frank Buono, the Two-Axis Dolly operator, who was seated in a translucent cabin above the dolly. The camera car was steered by two low-riding drivers, one in front and one behind (when driving in reverse). Lubezki explains that the one-shot sequence actually contains a couple of seamless cuts, such as one at the time of a bullet impact and one as the camera leaves the car to follow Faron outside.

Looking back at the challenge of shooting an entirely handheld film that avoided coverage and lighting, Lubezki reaffirms his admiration for Cuarón. “You need a great director to take these kind of chances. Our argument over handheld vs. Steadicam was the first time we’d had a disagreement, and in the end, I think he proved me wrong.” Using the Spanish slang for chutzpah, he adds, “Cuarón said he wanted the film to have huevos, and it does.”

Super 1.85:1 (Super 35mm for 1.85:1 extraction)

Arricam Lite; Arri 235 Arri/Zeiss Master Primes

Kodak Vision2 Expression 500T 5229

Digital Intermediate

Printed on Fuji F-CP 3513DI

The cinematographer earned an ASC Award for his outstanding work in the pictures, as well as an Academy Award nomination and other honors.

For more shots from the movie, see our AC Gallery for Children of Men.