Cinerama Goes Dramatic for How the West Was Won

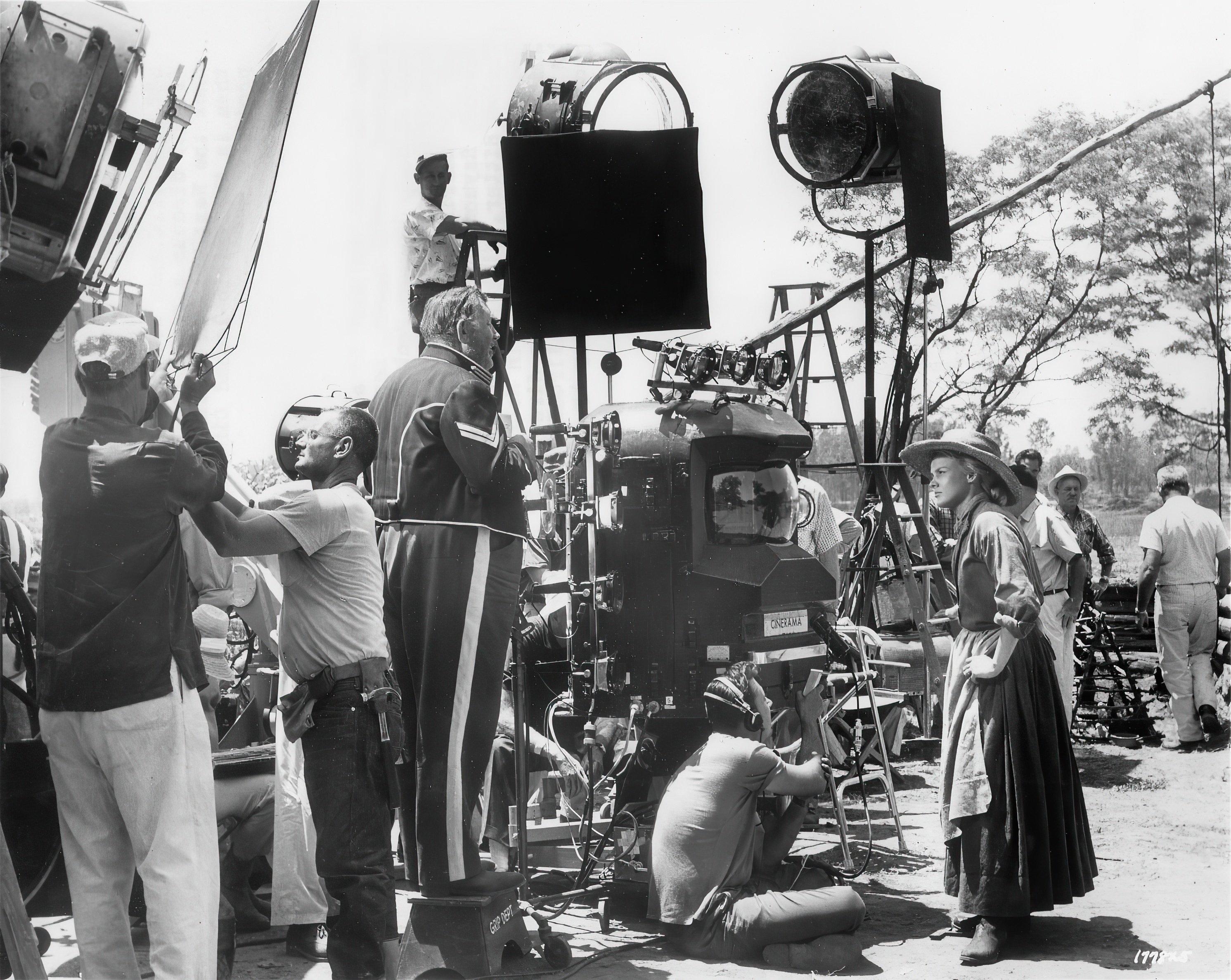

Photographing this dramatic feature in Cinerama posed some interesting problems never before encountered with the camera that introduced the first commercial super-widescreen motion pictures.

This article first appeared in AC, Jan. 1962. Some images are additional or alternate.

How the West Was Won, a Metro Goldwyn Mayer-Cinerama production, is the first dramatic picture to be photographed in the Cinerama process. Along with Charles Lang, Jr., ASC and Joseph LaShelle, ASC — who photographed other segments of this production — I had the rewarding experience of directing the photography of segment No. 2, which stars Debbie Reynolds and Gregory Peck, and which was directed by Henry Hathaway and produced by Bernard Smith.

Applied to the production of a dramatic picture, Cinerama poses many new and interesting problems, both for the director and the director of photography. It presents certain limitations, too, in contrast with conventional single-camera photography. The major one, perhaps, is that posed by the camera’s three 27mm lenses which, together, take in a field of view 143 degrees wide and 55 degrees high and record it on three separate strips of 35mm film.

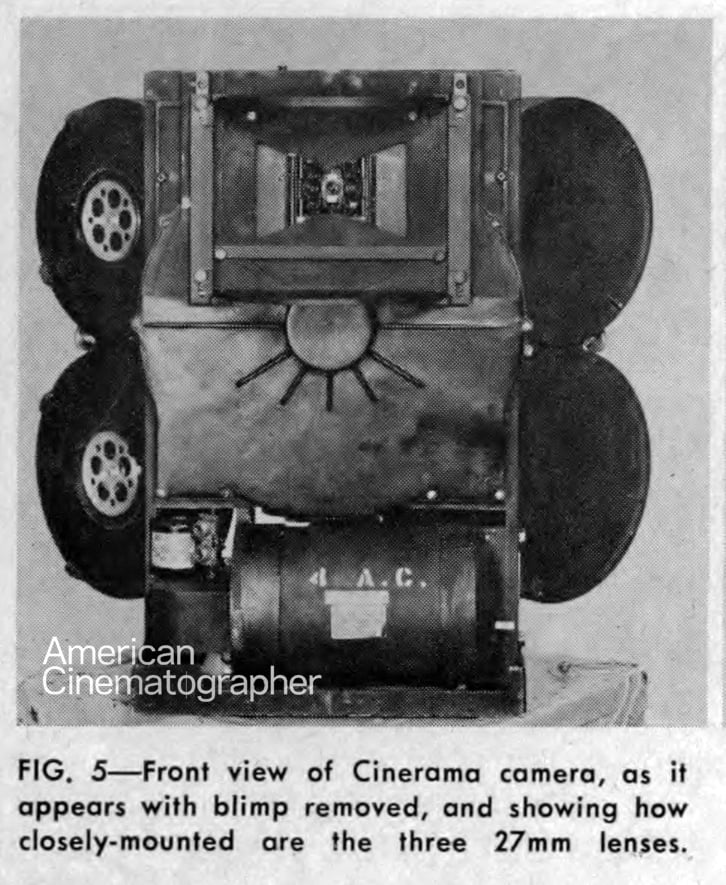

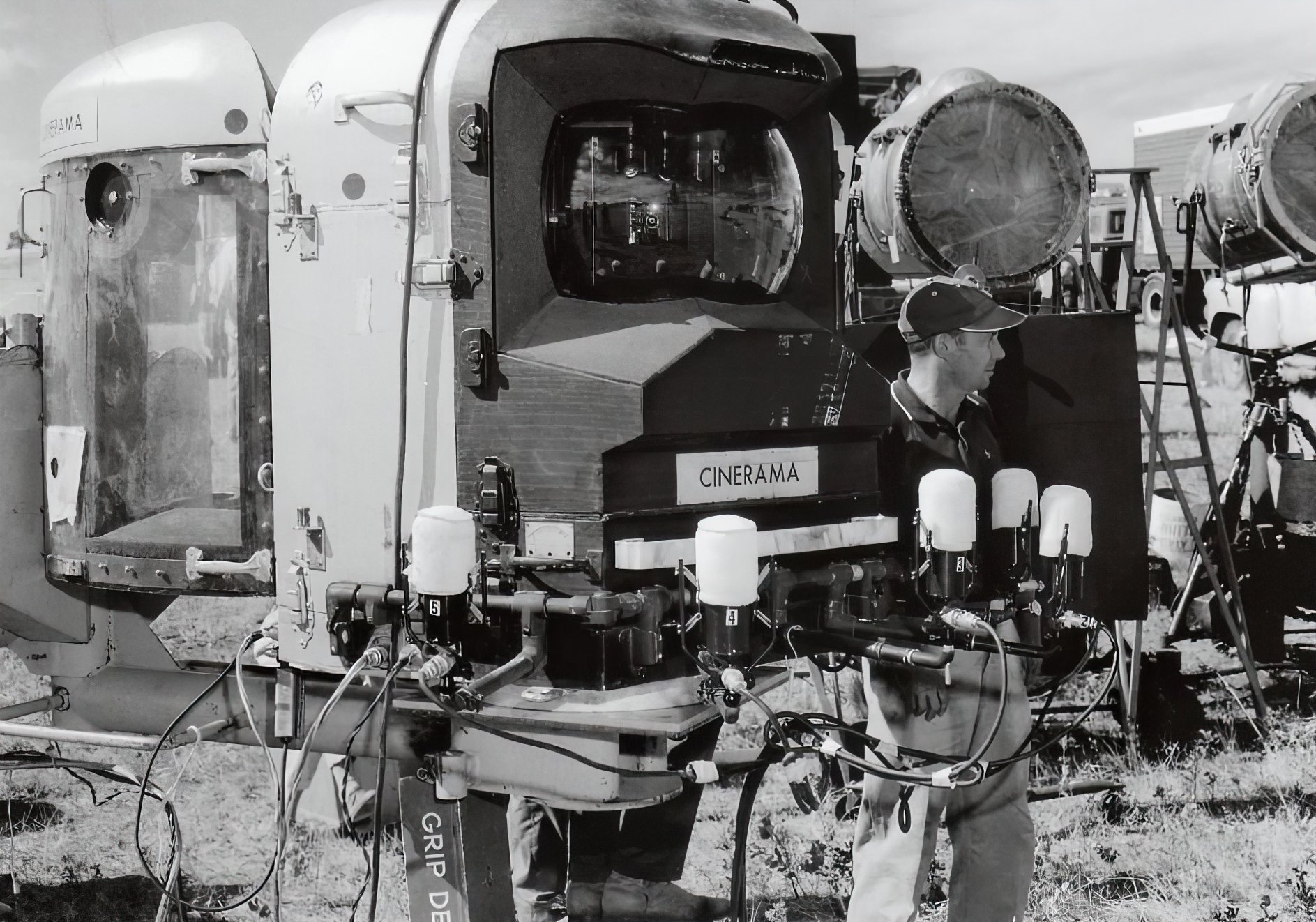

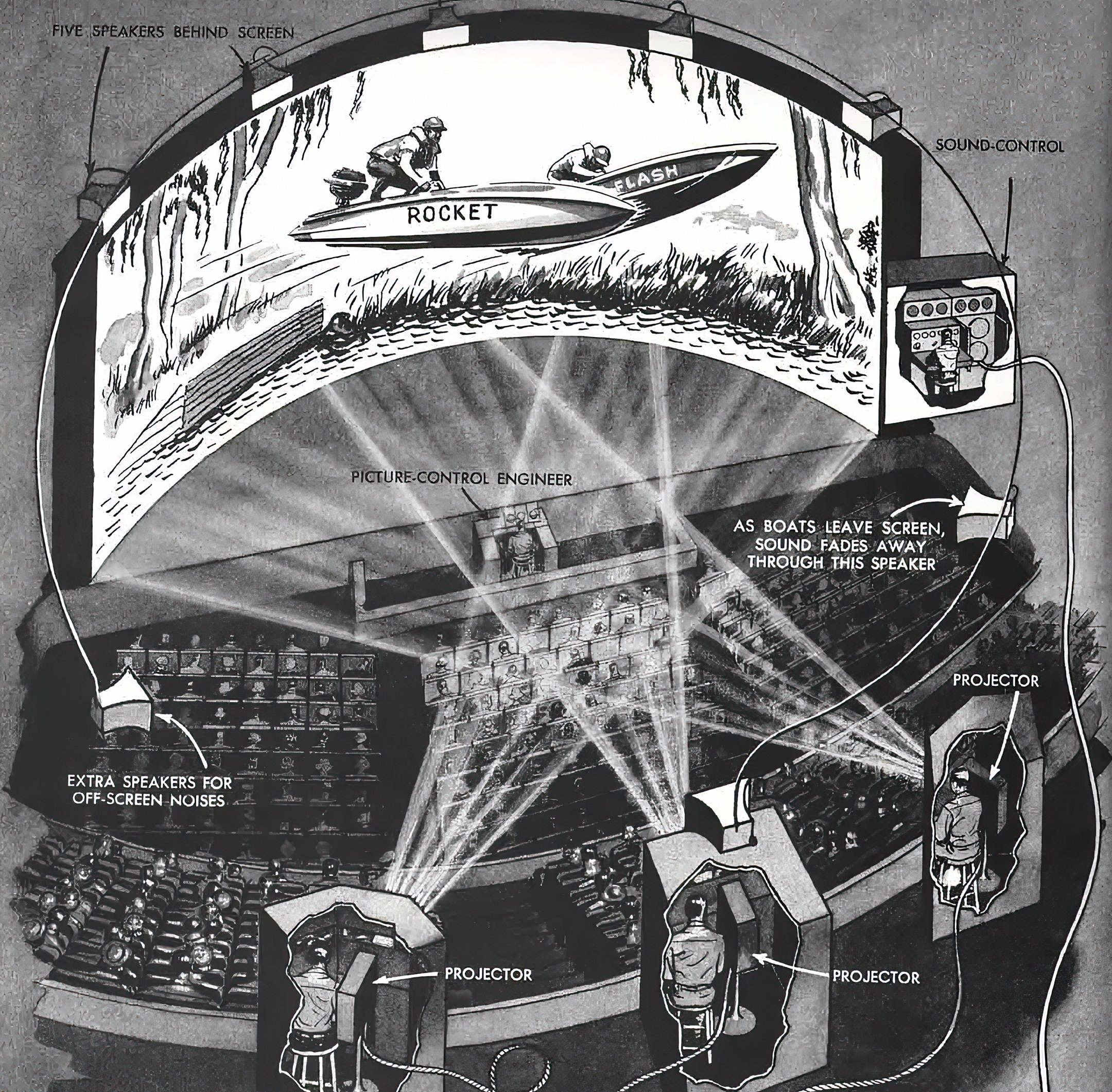

The Cinerama cameras we used to photograph How the West Was Won are basically the same as those which have been used to photograph Cinerama travelogues since 1952. A Cinerama camera is actually three cameras in one — that is, three separate negatives run through the camera past three lenses, which cover the system’s 143° X 55° aspect ratio, and record one-third of the scene on a frame of each negative. A single rotating shutter moving in front of the lenses at a point where their lines-of-view cross, effects the simultaneous exposure on the three strips of film. (See Fig. 5 below.)

Prints of the resultant negatives are shown with three projectors which screen the three film strips at precisely the same angle of view which they were photographed, so that the images become one — of super-wide-angle dimension — on a large horizontal curved screen.

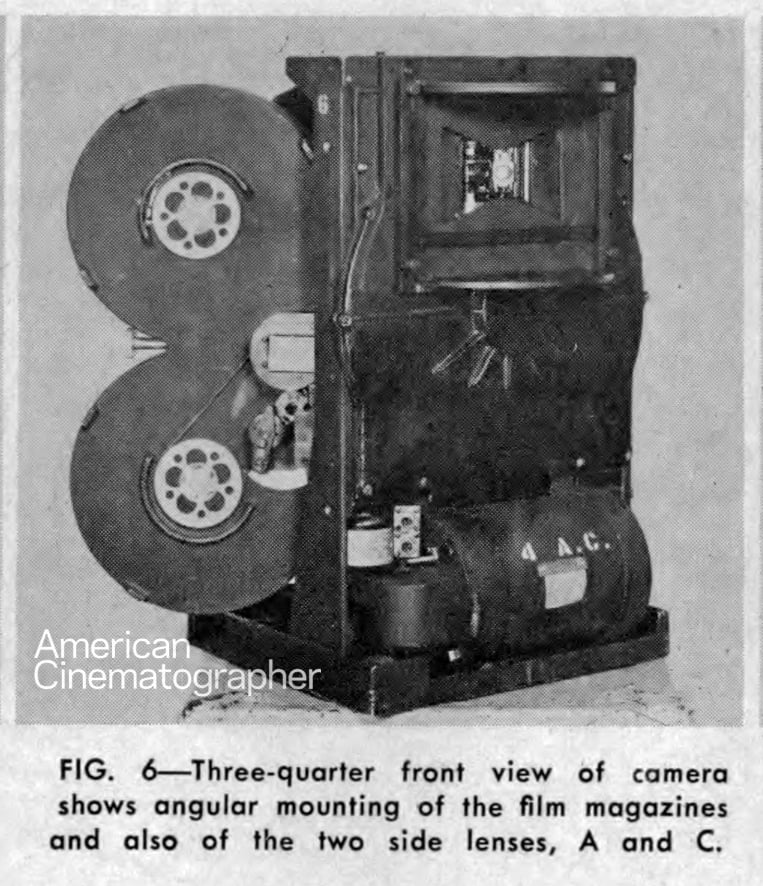

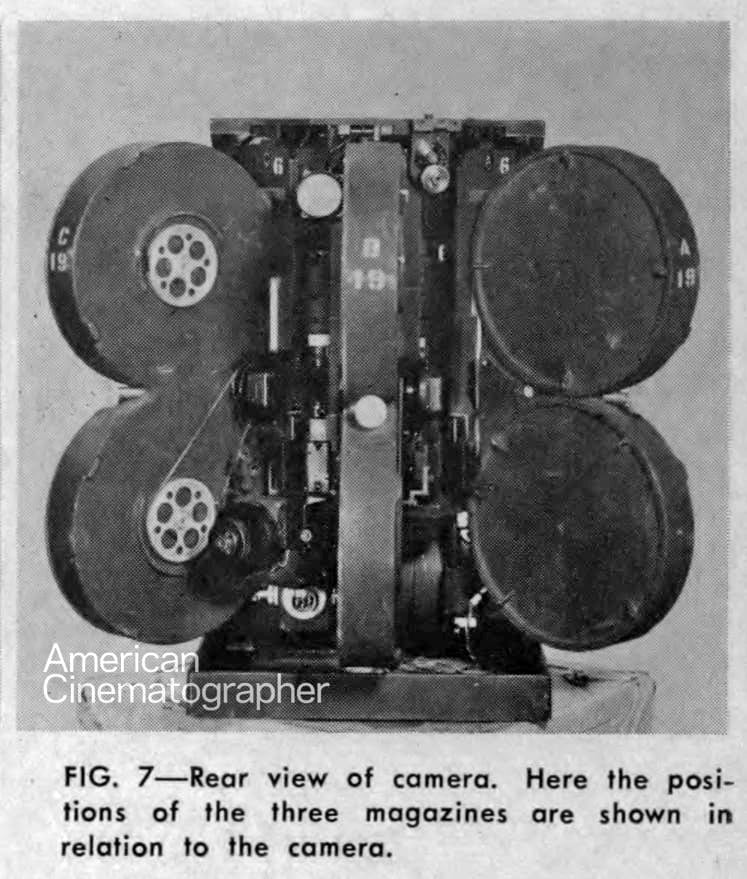

The camera, exclusive of the film magazines, consists of the shutter, lenses, motor, and driving mechanism. There are three film movements, which are separate units — chambers about the size of a cigarette box — which are attached to the magazines prior to mounting on the camera. All three movements are interlocked, thus insuring absolute sync of the three films moving through the camera.

The exposure is variable, but not separately for each lens. The diaphragm controls of the lenses are interlocked so that it is impossible for one lens to be set at one stop and the other two at different stops. Each lens is precisely calibrated to insure highest accuracy, for there can be no difference in focus between the three frames of film which are recorded simultaneously and comprise a single “exposure.” The lenses are not immediately removable from the camera, as is the case with other production-type cameras, such as the Mitchell, and there is no lens turret. Actually, there isn’t room for a turret in that area of the camera where the lenses are mounted, as may be seen in Fig. 5., above.

This necessarily brief description of the Cinerama camera is given here to familiarize the reader with its design, components, and use in production so that he may better understand references that will be made to it in paragraphs that follow.

In the course of using the Cinerama camera, two descriptive terms developed which have since become standard with us. They are panel and blend line. Panel describes any one of the three segments of the 143-degree scene or picture area being photographed or projected. Blend line describes the line of demarcation between the three panels. Ideally, the blend line is imaginary, although it is often visible on the screen and it becomes one of the chief problems in Cinerama photography to minimize if not entirely eliminate any evidence of the blend lines. How we have dealt with this will be described later in this article.

The Limitations Encountered

In using the Cinerama camera to photograph a dramatic picture, the first limitation we encounter is that which the three 27mm lenses impose. With three lenses pointing in three different directions to photograph an outdoor scene, it is obvious that the chief problem is one of lighting. In bright sunlight in the afternoon, with the center lens pointing due west, the sun for the left side of the picture, or “A” panel, would be in a direct back-light position. The center panel “B” would have a direct cross light; and in the right or “C” panel, there would be strong but flat light. The entire three-panel scene, therefore, would consist of a back light, a cross light and a flat light — all in the same composition, but each in a separate segment of it.

It was pointed out earlier that the diaphragm controls of all three lenses are interlocked, so that it is impossible to set one lens at one f/stop and the other two at different stops in an effort to compensate for the different kinds and intensities of light that may fall on the three panels or segments of a scene. This is necessary to insure that sky exposures will be uniform in all three panels and thus conceal — or at least not readily reveal — the lines of demarcation between the respective panels on the screen. Exposure is variable, but not separately for each lens.

As the diaphragm controls are interlocked, it is necessary to arrive at a compromise in exposure for exteriors, such as described above, in order to accommodate backlight, cross light and flat light in one pictorial composition. Exposure calculation in every instance must be precise.

When shooting interiors on the sound stage, the first question posed by the 143-degree camera field of view is, “Where do we put the lights?” Because the camera’s 27mm lenses produce an unnatural aspect of depth, it is necessary to build all sets for Cinerama smaller than sets for conventional cinematography. They must be small and they must be high, because of the Cinerama picture format — 143 degrees in width by 55 degrees in height. Set design, therefore, requires special consideration. Take, for instance, little things like trim, moldings, etc. Because the camera is so close to the walls of a set when a scene is being photographed, such small details loom up — are more pronounced — than in 35mm photography.

For all Cinerama interiors, sets must have four walls, and sometimes a ceiling. This is because where the action involves a large group of people, over-the-shoulder (reverse angle) shots are inevitable. And if this is done properly, the camera will be moved or dollied. Without the fourth wall, the 143-degree wide-scope lenses would take in the open space where no wall was provided.

Our objective, in adapting the Cinerama camera to photograph a dramatic motion picture, is to use it with virtually the same freedom that we have when shooting with a Mitchell. Thus we are able to make the variety of shots so essential to smooth cutting of the film. A major problem has been making the wide scope of the scenic travelogue fit the smaller confines of the dramatic picture set. Now the camera is photographing principally people in dramatic action, and scenery becomes secondary. In other words, we now use the Cinerama camera the same as we would a camera of conventional picture dimension or aspect ratio.

One of the problems we have encountered in this so-called close-range photography with Cinerama, is shooting closeups. In order to shoot a waist-size closeup of a person, that person must be between two and three feet from the camera lens, because of the 27mm lens used. This close proximity of subject to camera makes lighting extremely difficult. With the blimp on the camera, the subject’s distance is further narrowed to something like 18 inches from the blimp’s transparent plastic “bubble.”

How do you light a person standing only 18 inches from the camera? In this case we used some tricky lighting devices — small lamps that were mounted on the camera blimp. Where, normally, we would use a key light well back and properly placed, we substituted the smaller blimp-mounted lamps having the proper output and set at the correct angle.

Because good motion pictures are partly the result of good editing, the cutter must have the proper shots to work with. Closeups make up a major portion of these shots, and for this reason we set out early to perfect a means of making acceptable closeups with the Cinerama camera.

Because people — the actors in the cast — are our primary objective, they must at all times dominate the scene instead of the scenery in exteriors, or dominate the set, when scenes are filmed on the stage. We have successfully applied most of the basic photographic techniques of 35mm photography to that of Cinerama in order to concentrate attention on the players — by proper lighting, the right camera setup, and giving special attention to how and where a player looks while the scene is being photographed.

The 3-Panel Bugaboo

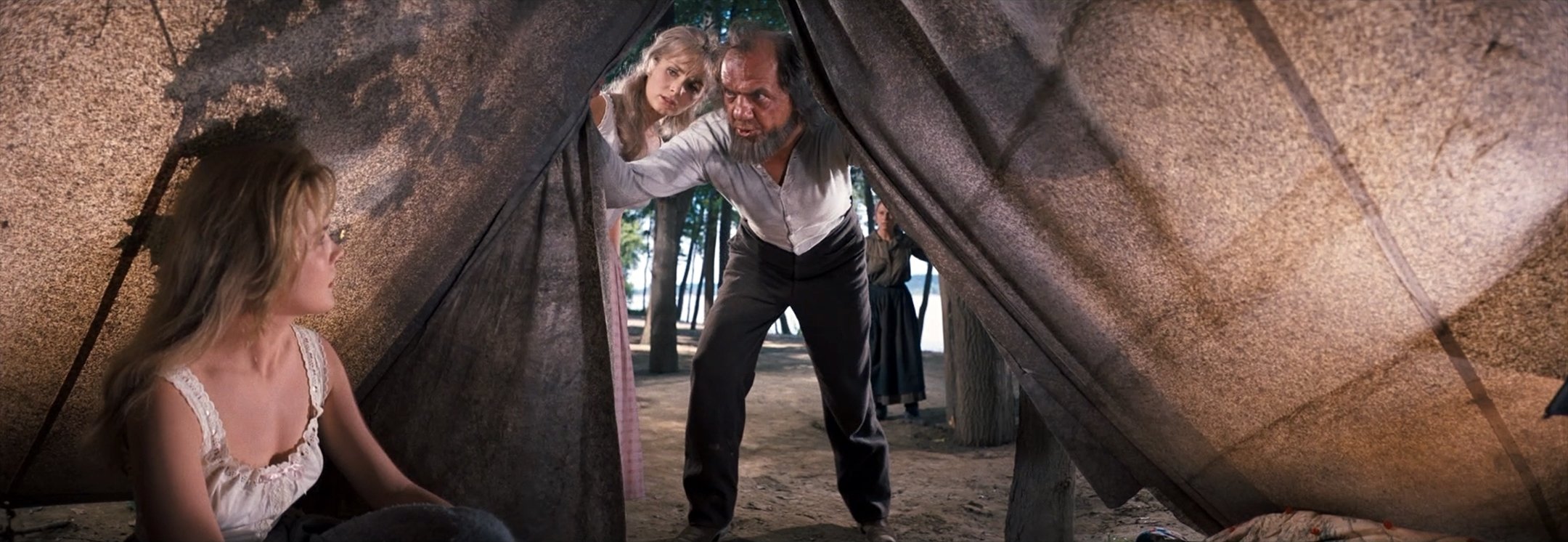

Whereas Cinerama’s three-panel format with its accompanying blend-lines constantly posed problems for the photographers of Cinerama spectacles, such problems are intensified when shooting a dramatic picture in this format. You cannot, for example, shoot a tight head closeup, CinemaScope fashion, with the Cinerama camera and have the image bisected by a blend line. Instead, the single actor must be so positioned that his head will be entirely within the boundaries of one of the three panels — preferably the center one.

Another problem is where we have, say, three actors in a scene — one in each panel. An actor in a side panel cannot look directly at one in the center panel when speaking to him, but must “cheat” a little — direct his eyes slightly behind the actor in the center. On the screen, his gaze will appear completely proper. This is because of the differences in the angle in which the side panel actor is photographed compared to the one in the center. Obviously, this, proves a little rough for the actors who, in such situations, have to play to the wall or some inanimate object in the background.

Still another limitation the Cinerama system places on an actor is where he can come to rest in a scene. If he does so at the point of either blend line, there likely will be a noticeable vertical streak bisecting him on the screen. Therefore, a dominant rule is that an actor moving in a scene can only stop in the areas designated by cue marks placed on the floor or ground. He can proceed through the blend line, but never stop there. Or move a hand or arm through it. All this makes it imperative that actors “hit” their marks accurately every time.

It also gives the camera operator one more thing to watch. Not only must he keep the actors in the picture. but he must be sure they are always in the right positions with respect to the panels and blend lines — and more important, that they are looking in the right direction in relation to other actors in the scene, as already pointed out above.

It is obvious to the reader by this time that the blend lines in the Cinerama process widely affect the photographic procedure as well as the conduct of actors in a dramatic production. Because the presence of the blend lines can be minimized by taking certain precautions, such as those already described, this is a major consideration both in planning the sets and in choosing Cinerama camera setups.

Minimizing the effect of the blend lines is therefore a major consideration whenever we prepare a camera setup. We look for verticals that can be placed at the point of the blend lines in a scene; and should we be working outdoors in a wooded area, we endeavor to place the camera so that trees come in this area in a composition. On the sound stage, we often use shadows to minimize the blend lines, arranging the lighting in such a way that the shadows appear natural to the scene.

When photographing exteriors with the Cinerama camera, the 55-degree vertical angle of view adds further to the problems imposed by the three panel format. For example, very early in the afternoon, we may get the sun in the picture and not be able to reposition the camera to avoid it. Here it becomes necessary to improvise means of obscuring the sun itself by introducing subtly into the scene a tree branch, cluster of foliage or other suitable object so it will come between the sun and the camera lenses.

The worst condition that can be encountered when shooting exteriors is a bald sky. When there is nothing that can be logically introduced into the scene to absorb or conceal the blend lines, then the camera setup should be changed. The bald sky is something we endeavor to avoid in Cinerama exteriors. We invariably consider the blend lines first, then plot and stage the action to suit the camera setup.

The Curvature Problem

The fact two of the camera lenses are set at an angle and that the composite Cinerama scene is projected on a curved screen causes any strong horizontal lines in the scene to zoom sharply upward in the side panels when the picture is projected. A typical example of such a scene would be a train moving across the screen in the middle foreground. If the train were to enter the picture from the right, it would appear to move diagonally downward until it reached the first blend line, then move straight across to the next blend line, and from there zoom diagonally upward again and out of the picture. The answer to this problem, of course, is simply to avoid such camera setups.

The three-panel curvature problem works adversely in still another way; it prevents shooting with the Cinerama camera in other than a perfectly level position. In other words, the camera cannot be tilted up or down more than “half-a-bubble” on the level, nor can it be tilted or panned during shooting. Providing it is kept level, it can be moved on a crane back and forth laterally or moved in and out or in any other direction. Thus the camera can never be elevated then tilted down in order to circumvent the high-walled sets which the system presently requires.

There are other problems that walls present in Cinerama photography, and these are matters which the production designers are now recognizing so that, for the director of photography, they present no unsurmountable situations. As in all motion picture production, sets must be specifically designed to accommodate the conditions which are an inherent part of Cinerama’s three-panel photographic process.

On the set, the director of photography and his operator have plenty to do. Both must be equally alert, for there is so much to watch: the blend line positions; how the light is falling on the players; making sure none of them move into the wrong light, or stop at the point of a blend line. You are three times as busy as you ever were shooting a conventional picture.

With all the problems that Cinerama presents the director of photography in the production of a dramatic picture, an understanding and sympathetic director can do much to ease the task and make the photography completely successful. Such a director is Henry Hathaway, who was just wonderful in his planning of this picture — a leader in it, actually. Because of this, we were able to utilize the full potentials of the Cinerama camera to give scope and life to scenes such as never before witnessed in a dramatic picture.

When you see the film projected in an approved Cinerama theater, and the results on the screen are right; when you have accomplished all that you set out to do photographically, the actors have held their positions, and the blend ilnes are adequately camouflaged, then you realize that as a medium of screen entertainment, Cinerama provides the greatest audience participation in the world.

This AC retrospective article goes into further detail on the production. And this article examines the history of widescreen cinema.

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.