What is Widescreen?

Celebrated during this year’s 39th ASC Awards ceremony, here’s a brief history of panoramic cinematography and the inventive systems that helped bring it to the screen.

This story was originally published in the 39th Annual ASC Awards program book. Some images are additional or alternate.

For the sake of discussion, let’s agree that any motion picture with an aspect ratio beyond the Academy aperture of 1.37:1 can be described as “widescreen.”

What epic images come to mind when thinking of widescreen cinema? Perhaps shots from such classic Westerns as How the West Was Won, Once Upon a Time in the West or Unforgiven?

Historical epics including Ben-Hur, Braveheart and Titanic?

Sci-fi and fantasy spectaculars such as 2001: A Space Odyssey, Blade Runner and the Lord of the Rings trilogy?

Lavish musicals including Oklahoma!, West Side Story and Wicked?

Celebrating widescreen cinema, here’s the opening reel created for this year’s ASC Awards for Outstanding Achievement in Cinematography, cut by Benjamin Mehr:

Widescreen cinema is commonly associated with feature films starting in the 1950s. But the concept of a employing a panoramic frame goes back much further, in fact, even before celluloid negative was a thing.

In his 1930 American Cinematographer article “The Early History of Wide Films,” Carl Lewis Gregory described an cinema landscape in which there were no technical standards, as manufacturers experimented with a wide variety of frame rates, film gauges and aspect ratios. He details one widescreen example as “a scene taken in the Champs-Élysées in Paris in 1886 by [French inventor and chronophotographer] Dr. Étienne-Jules Marey. Although the ‘film’ was paper — sensitized celluloid not being available until a year or two later, and cine projectors having not yet been invented — this paper negative could be printed as a positive film and run as a Fox Grandeur [70mm, 2.13:1] film today.”

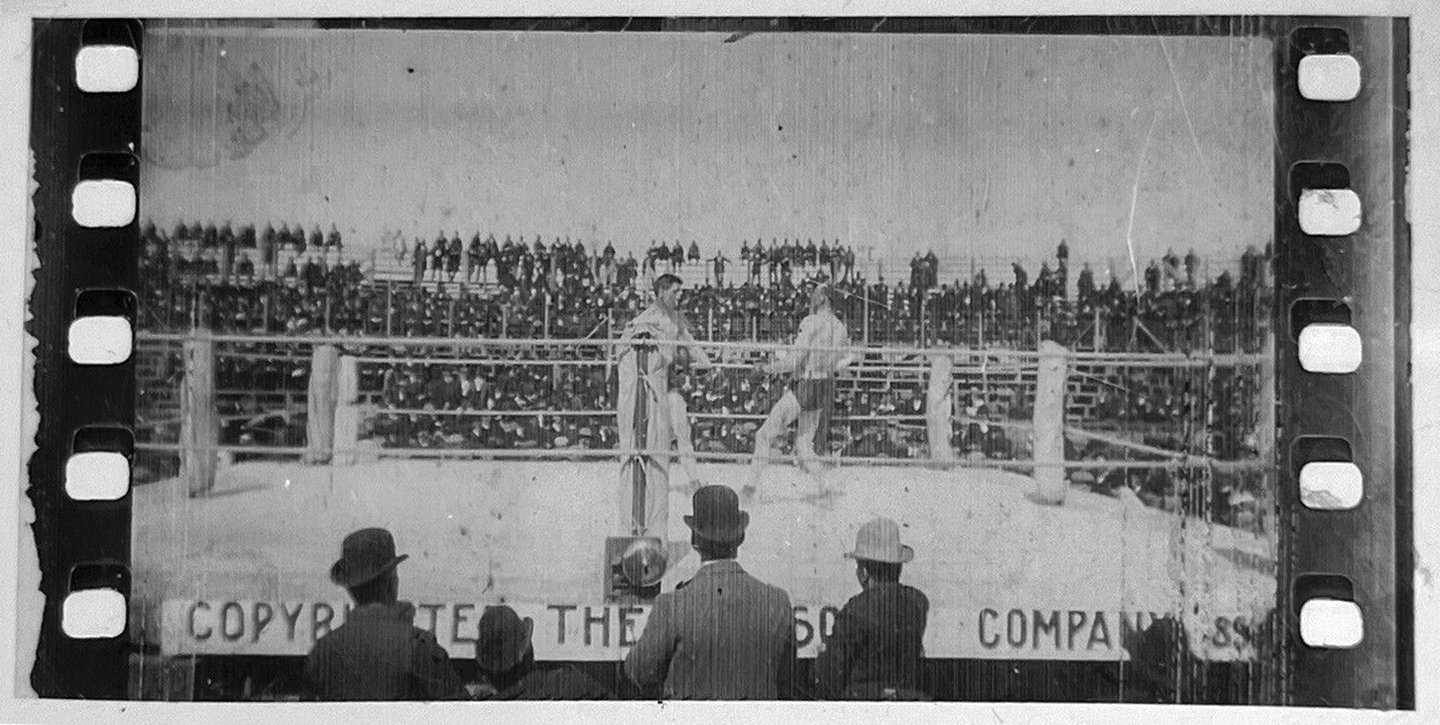

Shot in the Veriscope (1.65:1) format, the sports documentary The Corbett-Fitzsimmons Fight (1897) was perhaps the first widescreen feature-length film, employing 63mm Eastman Kodak nitrate stock. For cinematographer Enoch J. Rector, an early cinema pioneer, the Veriscope process was essential to capturing both boxers in the same frame and never missing a punch.

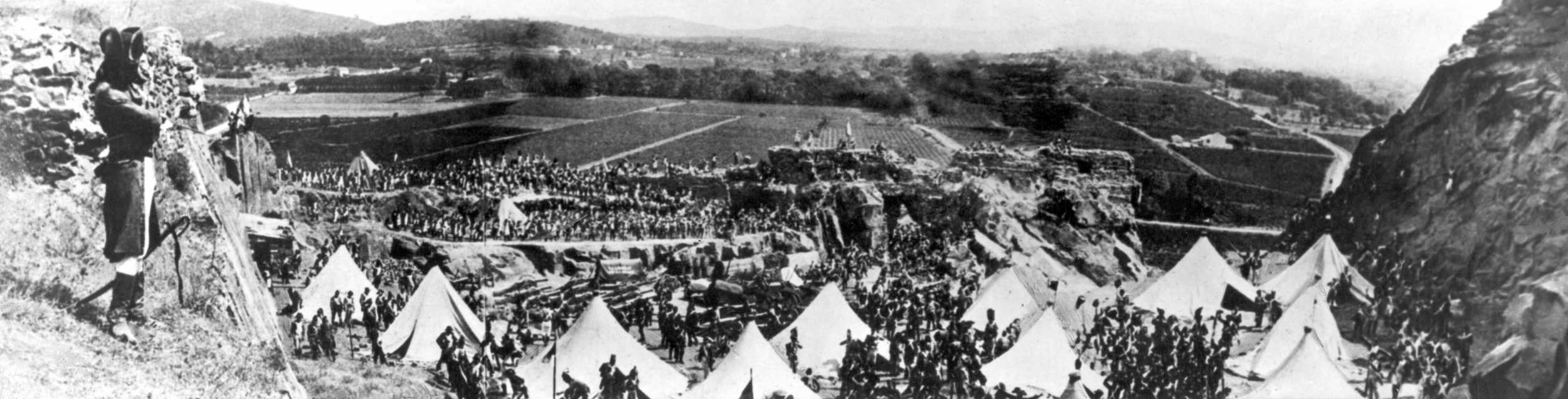

French director Abel Gance presented the epic finalé to his historical drama Napoleon (1927) in what became known as Polyvision — a unique 35mm widescreen (4:1) presentation format that employed three projectors to simultaneously present an onscreen tryptic of 1.33:1 images.

“From my experience with 70mm cinematography, I can confidently say that the wider film is not only the coming medium for such great pictures, but that it will undoubtedly become the favored one for all types of pictures.”

— Arthur Edeson, ASC

The widescreen Western epic The Big Trail (1930) — shot using the 70mm Fox Grandeur process by ASC members Arthur Edeson and Lucien Andriot — premiered at Grauman’s Chinese Theatre in Hollywood just around the corner from the ASC Clubhouse. Edeson noted, “From my experience with 70mm cinematography, I can confidently say that the wider film is not only the coming medium for such great pictures, but that it will undoubtedly become the favored one for all types of pictures.”

Unfortunately, The Big Trail was not a success due to the lack of theaters equipped to project 70mm, essentially bankrupting Fox, and the Great Depression soon quashed such experiments. World War II then stalled further developments in camera and exhibition technology.

But as theatrical motion pictures faced off with broadcast television in the 1950s, a surge of new motion-picture technologies were designed to entice audiences from their living rooms and back into theaters. In her AC article “Scale and Spectacle,” Dawn Fratini detailed this progress, noting that “widescreen, large formats, stereophonic sound, 3D, and drive-ins all promised audiences a bigger and more immersive movie-going experience.” Something they could not get at home.

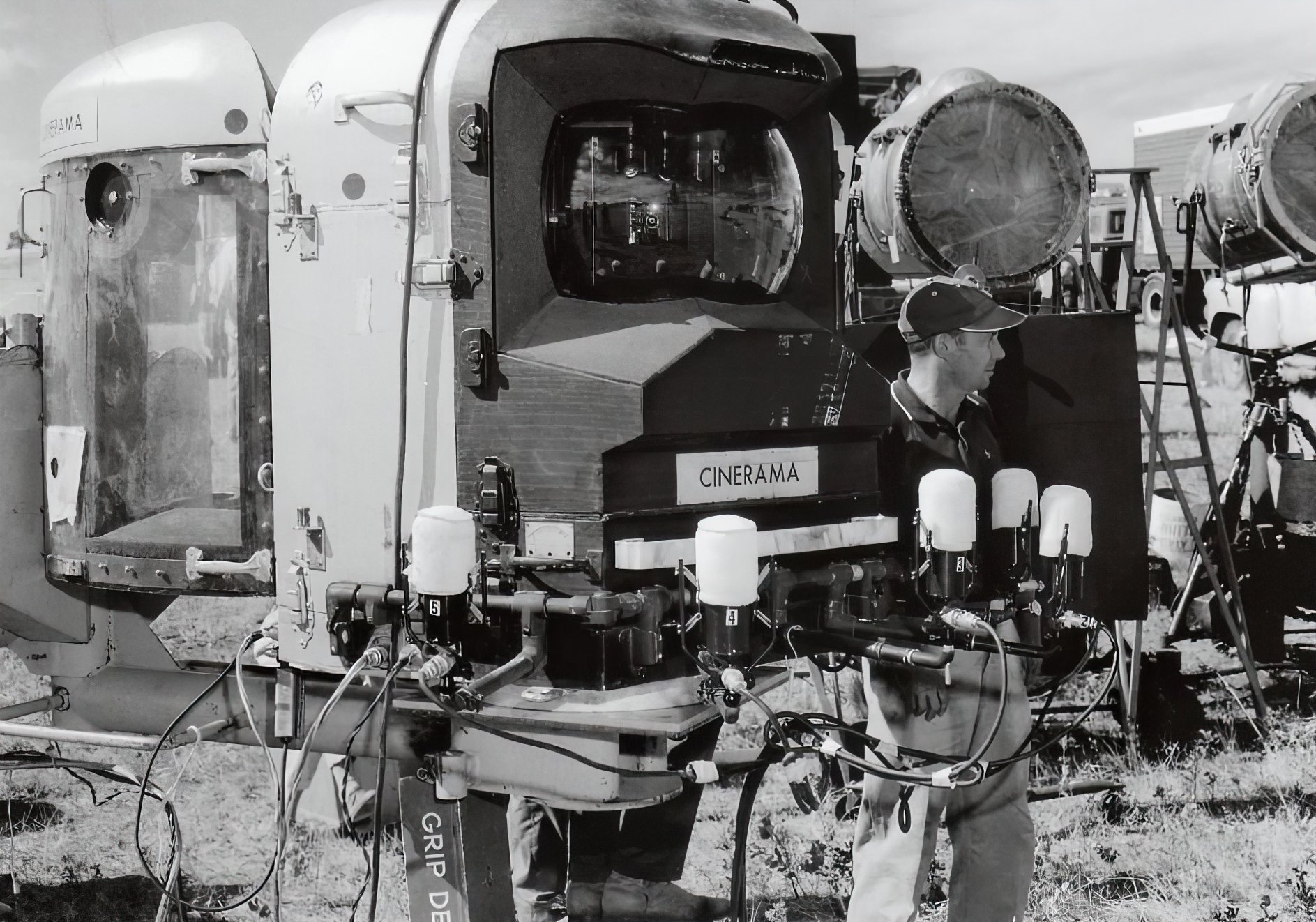

The most lasting change came in the form of widescreen options: “By 1955, AC could report six ‘well-established methods’ for achieving widescreen imagery. The first to debut was Cinerama, filmmaker/inventor Fred Waller’s three-camera panoramic system, which opened in New York in late 1952 and became a quick success, best known for the historical epic How the West Was Won.

“But because Cinerama required three tandem cameras, three tandem projectors and an enormous, curved screen, it ultimately proved too unwieldy and expensive for widespread use.”

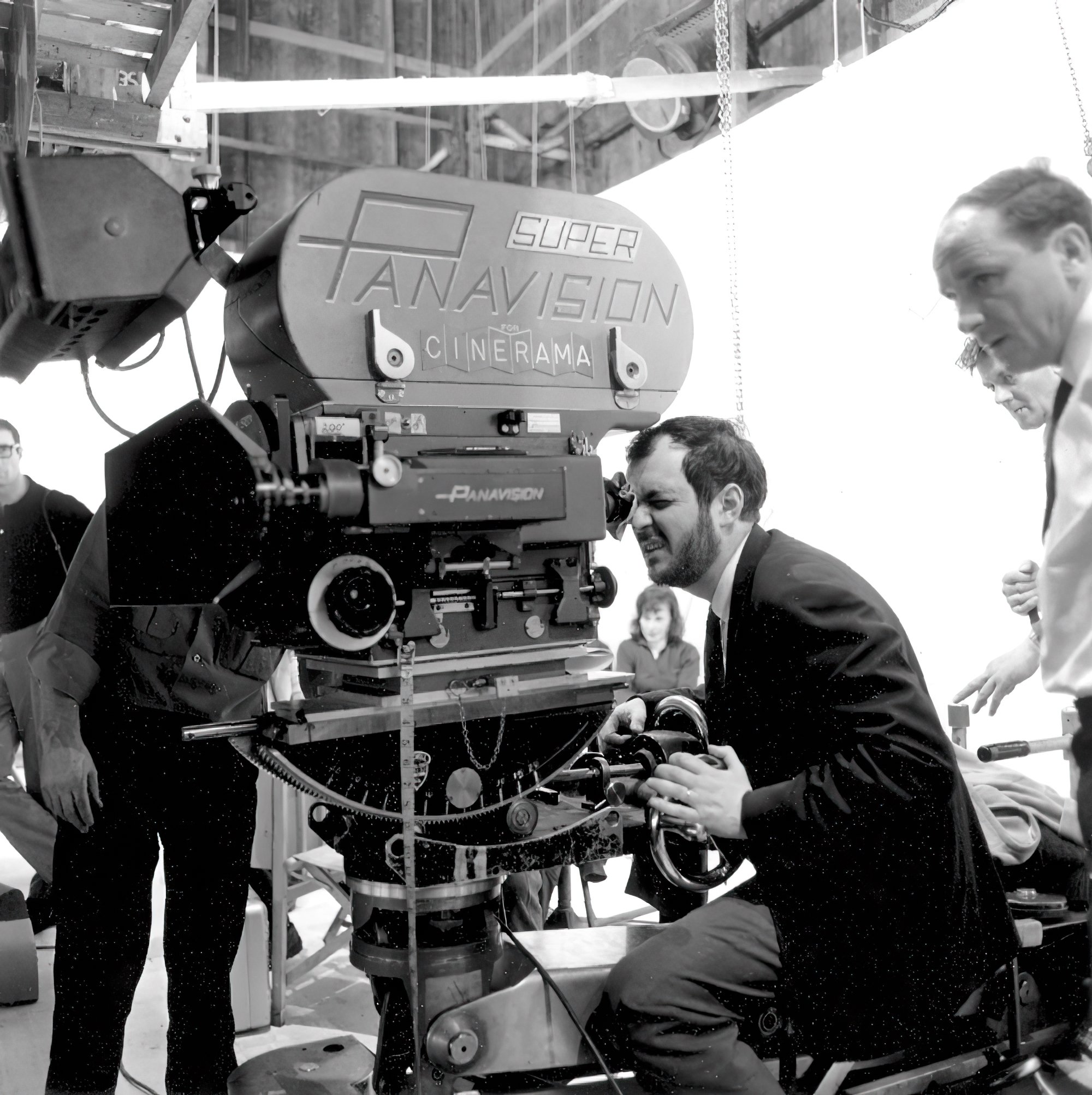

Later, 65mm camera systems were used to create such "single-lens Cinerama" projects as 2001: A Space Odyssey, Grand Prix and It‘s A Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World, among others.

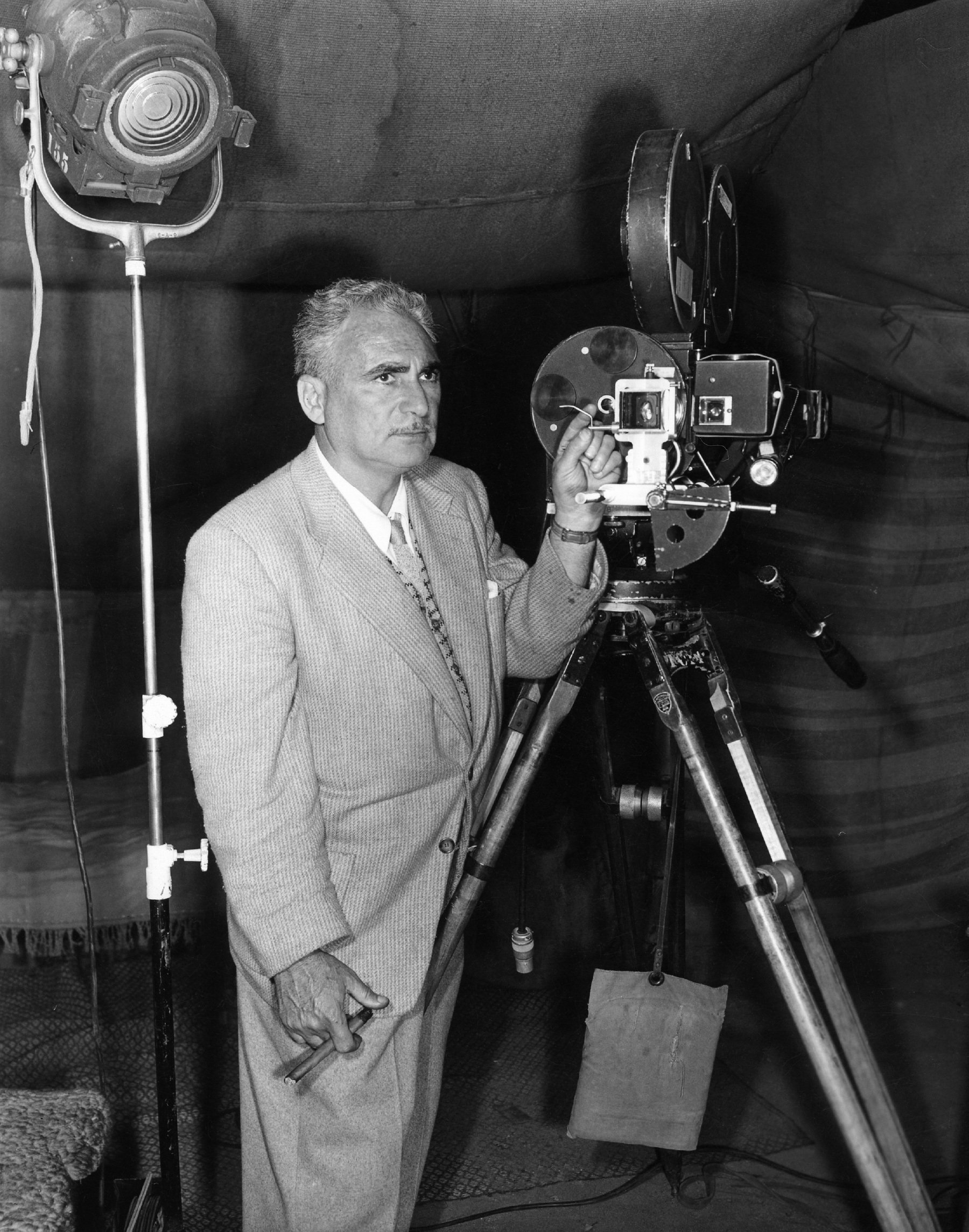

Seeking a new widescreen method that could use standard 35mm cameras and film, Earl Sponable, head of research at Twentieth Century Fox, was tasked with coming up with an alternative. Assisted by Sol Halprin, ASC, Fox’s executive director of photography, Sponable developed CinemaScope from a 1920s optical system designed by French inventor Professor Henri Chrétien.

His anamorphic hypergonar lens “squeezed” a wide image — with an aspect ratio ranging from 2.35:1 to 2.66:1 — onto a regular 35mm negative, which would then be expanded back out to its wider dimensions via a complementary anamorphic attachment affixed to the projector.

Fox’s proprietary CinemaScope process made its public debut with the Biblical epic The Robe in 1953 and was heralded in AC as “a new horizon in motion-picture technique... the greatest development since the introduction of sound.”

The CinemaScope process was rapidly adopted thanks to its relative ease of use, and the eventual improvement upon and popularization of this technique by Panavision soon opened up new opportunities for filmmakers around the world.

This forever divided motion pictures between those shot with spherical lenses — often described as “flat” — and those shot with anamorphic optics. In their design, spherical lenses more closely resemble the basic mechanics of the human eye, resulting in an overall naturalistic image from which the cinematographer can add creative character. In compressing — or “squeezing” — a far wider field of view onto roughly the same film frame or sensor size, anamorphic lenses render unique visual characteristics, including bokeh shape, edge falloff and the flaring of specular highlights. All are unique to the design and manufacture of the lenses at hand, offering cinematographers additional opportunities to shape their images.

Other widescreen systems introduced in the 1950s were Paramount’s VistaVision, which achieved a wider image (up to 2.00:1) by running 8-perf 35mm film horizontally and exposing a larger image area; Todd-AO, which utilized 65mm film shot at 30 fps; Fox’s TFC 4X-55 MM, essentially a 55mm version of CinemaScope; and Superscope 235, a spherical 35mm process developed for RKO in which a widescreen image is extracted from a the exposed negative, squeezed in the lab while printing, and unsqueezed during projection.

As the decade progressed, more systems involving combinations of anamorphic lenses and large-format film expanded the options for cinematographers, including MGM Camera 65, which later evolved into Ultra Panavision 70.

A multitude of further widescreen innovations were soon introduced around the world, such as Techniscope, a 2-perf, 2.33:1, 35mm process developed in Italy and used to shoot such films as The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. J-D-C Scope, a 2.35:1 system was devised by English innovator Joe Dunton, BSC. ShawScope, a version of CinemaScope, was introduced in Hong Kong. Sovscope, a process using LOMO anamorphics, was created in Soviet Russia and used to shoot films including Solaris.

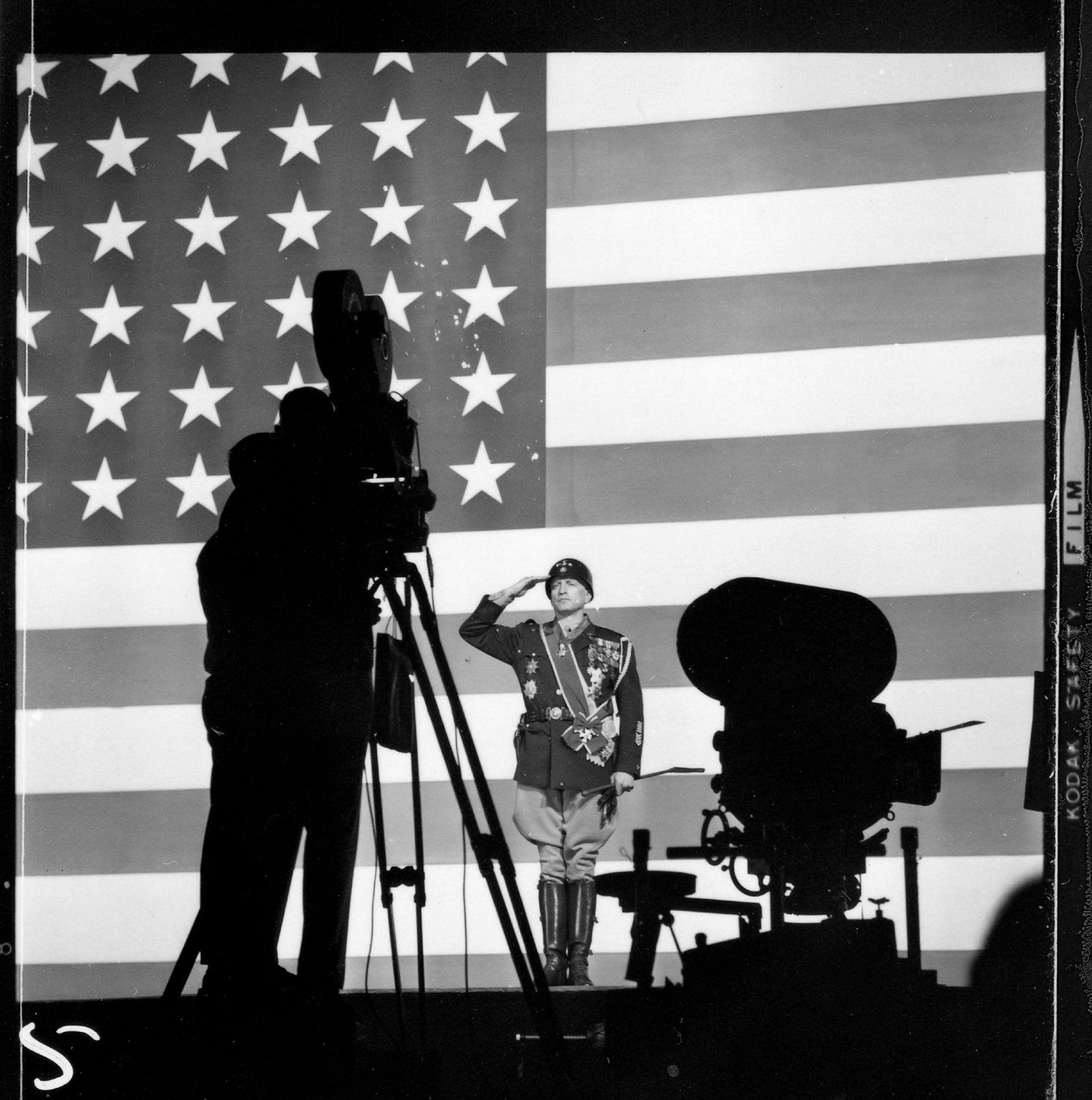

Back in the U.S., Todd-AO was briefly revived with new lenses as Dimension-150 to shoot Patton and The Bible, while the spherical Super 35 widescreen process — a revival of Superscope 235 — was widely used to great effect in numerous films, from Top Gun to Titanic to No Country for Old Men.

Today, digital technology — in production, post and exhibition — allows filmmakers an infinite array of choices when determining what aspect ratio will best serve their story, from offering multiple compositions within a single scene to composing a bespoke frame from footage shot with an anamorphic system to take creative advantage of desired optical artifacts.

A new wave of anamorphic lenses — from established companies including Angénieux, Arri, Cooke, Leitz, Panavision and Zeiss, to newer ones such as Atlas, Hawk, Laowa, P+S Technik, Rokinon and Viltrox — now offer cinematographers an almost endless array of options.

Today’s filmmakers are also rediscovering vintage widescreen solutions, from Robert Richardson, ASC shooting Quentin Tarantino’s The Hateful Eight in 2.78:1 Ultra Panavision 70 — a 65mm anamorphic format that had been in mothballs for decades — to Lol Crawley, BSC filming this year’s The Brutalist in the venerable VistaVision using the compact Beaumonte camera.

Always seeking distinctive creative options when bringing stories to the screen, cinematographers will continue to inspire innovation. And for more than a century, widescreen motion pictures have been part of that discussion with their collaborators.