A Cop Gone Wrong: Touch of Evil

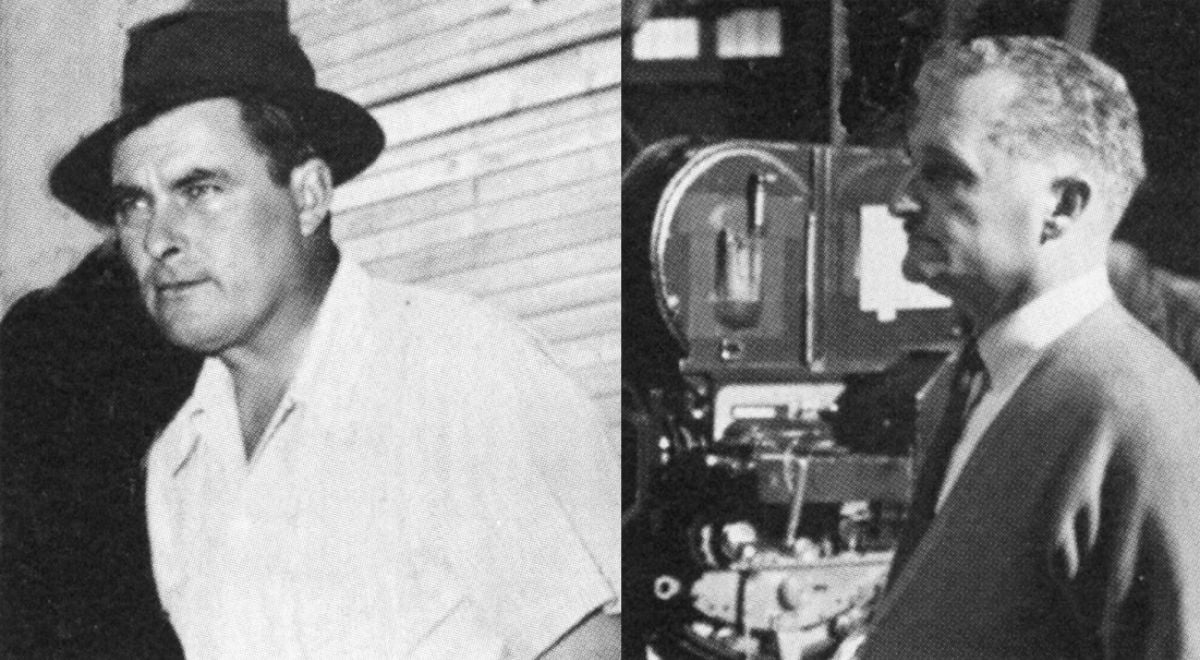

Orson Welles and Russell Metty, ASC lent cinematic panache to this classic noir thriller whose script was rescued from the reject pile.

This article was originally published in AC, Sept. ’98. Some images are additional or alternate.

“A policeman’s job is only easy in a police state," Charlton Heston tells Orson Welles in Touch of Evil. "That’s the whole point, Captain. Who’s the boss, the cop or the law?"

This rhetorical question lies at the heart of Welles’s moody and evocative 1958 movie. In exploring the time-tested theme, Orson Welles, a wildly variegated cast and a sturdy Universal production crew lead viewers through a shadowy maze of strange people, crime, squalor and moral decay. The result is a 20th-century American version of a yarn that might have been spun by Charles Dickens or Victor Hugo.

The production history of Touch of Evil is almost as colorful as its story. Universal, renamed Universal-International following its merger with International Pictures, had purchased film rights to Whit Masterson’s pulp novel Badge of Evil and put it on producer Albert Zugsmith’s slate for the 1947-’48 season. U-I had sworn off making B movies, but the studio had kept Zugsmith in the “nervous A” budget category because he specialized in “exploitation pictures.” These made money because of their sensational qualities rather than extravagant production values. Most but not all were potboilers. Certainly the 1957 pictures The Incredible Shrinking Man and Written on the Wind were nothing to be ashamed of.

Dumping Zugsmith and Welles into the same crucible would seem as aberrant as pouring ketchup on ice cream. Given an almost generous budget (just short of $900,000) and a five-week shooting schedule, Zugsmith went all-out to gather a prestigious cast. He first signed Orson Welles, thus spurring the interest of Charlton Heston (who was in the spotlight for his performance as Moses in Cecil B. DeMille’s 1956 religious epic The Ten Commandments), and then hired the increasingly popular Janet Leigh. Heston okayed Paul Monash’s script, but said that his decision would ultimately depend upon who was chosen to direct. He dropped the hint that Welles himself was a pretty fair director.

Welles had not directed a movie in the United States since Republic’s Macbeth in 1948. He had recently returned from Europe to produce King Lear on Broadway and was hoping to re-establish himself in American movies. According to Zugsmith, Welles asked which of his projects had the worst screenplay; the producer replied that it was probably Badge of Evil. Welles said he would direct the project if he could have two weeks to rewrite the script. It is probable that Welles was given the writer-director job (without extra pay) in order to lure in Heston and Leigh.

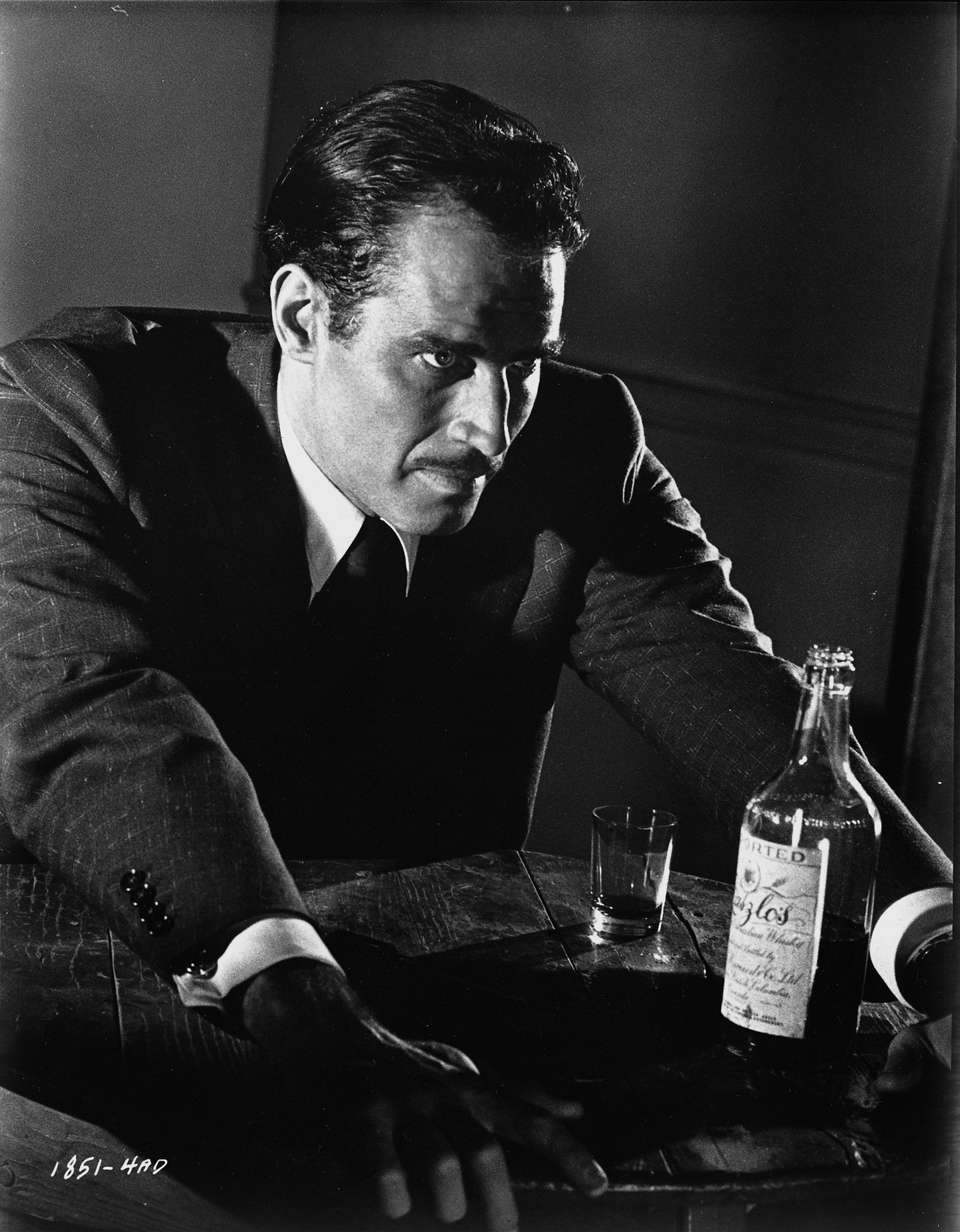

In his rewrite, Welles changed the tale’s locale from San Diego to the fictitious border town of Los Robles, a decaying dumping ground for criminals and other vagrants. The book’s hero, an Anglo detective with a Mexican wife, became lantern-jawed Mike Vargas (Heston), chairman of the Pan-American Narcotics Commission, whom we meet as he is honeymooning with his Anglo bride, Susan (Leigh). The two are walking on the United States side of the border checkpoint when they see a millionaire and a blond stripper blown to bits by an incendiary car bomb. Unofficially, Vargas joins famed American police captain Hank Quinlan (Welles) and his worshipful assistant, Pete Menzies (Joseph Calleia) in the investigation. When Vargas realizes that Quinlan is framing a Mexican youth for the crime, he becomes determined to expose the corrupt cop. He soon enlists the aid of Schwartz (Mort Mills), an assistant district attorney who points him toward evidence that Quinlan used manufactured evidence to send numerous murder suspects to death row.

Meanwhile, the leader of the Grandi gang, "Uncle Joe" (Akim Tamiroff), who hates Vargas for sending his brother to prison, connives with Quinlan against the upstanding attorney. As Vargas becomes enmeshed in his quest, Grandi’s goons terrorize Susan at an isolated motel, inject their terrified victim with sodium pentathol to make her appear to be a heroin addict and deliver her to a sleazy hotel room. Arriving on the scene, Quinlan strangles Grandi and leaves the body on Susan’s bed.

However, even the faithful Menzies turns against Quinlan when he finds the captain’s cane near Grandi’s body. Torn by conflicting emotions, he wears a hidden mike and accompanies the drunken Quinlan on a nocturnal prowl through an oilfield dump. Vargas follows and records their conversation, which reveals Quinlan’s villainy. Catching onto the setup, Quinlan shoots his sidekick. He is about to kill Vargas as well, but the dying Menzies manages to gun down Quinlan in the nick of time.

Instead of using the Universal backlot’s border town set, Welles and art directors Alex Golitzen and Robert Clatworthy elected to transform areas of the colorful oceanfront city of Venice into Los Robles. A beautiful city built to resemble its Italian namesake complete with Mediterranean architecture, canals and gondoliers, Venice had fallen on bad times. The waterways and bridges had gone to pot, many of the downtown buildings were run-down, and the area had become a high-crime zone. Because most of the film’s exteriors were shot night-for-night, the city also proved to be a gigantic lighting job. There are many deep-focus shots looking up and down long streets past the landmark series of arches, some of which are still there today. To add the appropriate ambiance, studio technicians dumped trash everywhere, and wind machines swirled the debris around.

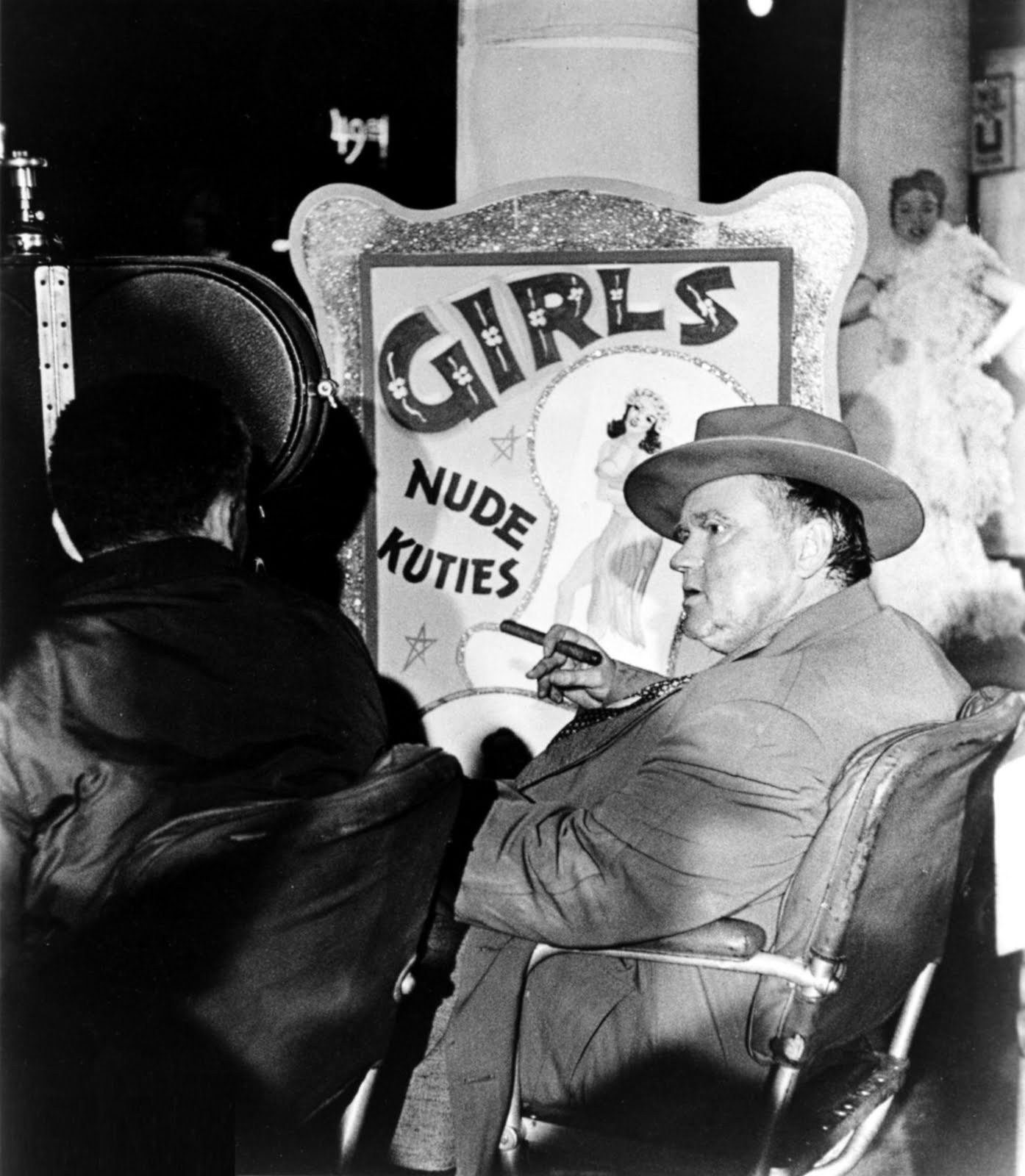

Russell Metty, ASC, who was employed at U-I when Welles arrived, had previously shot the filmmaker’s 1946 effort The Stranger. The big, cigar-smoking cinematographer was just the man to put Welles’s wildest notions onto film.

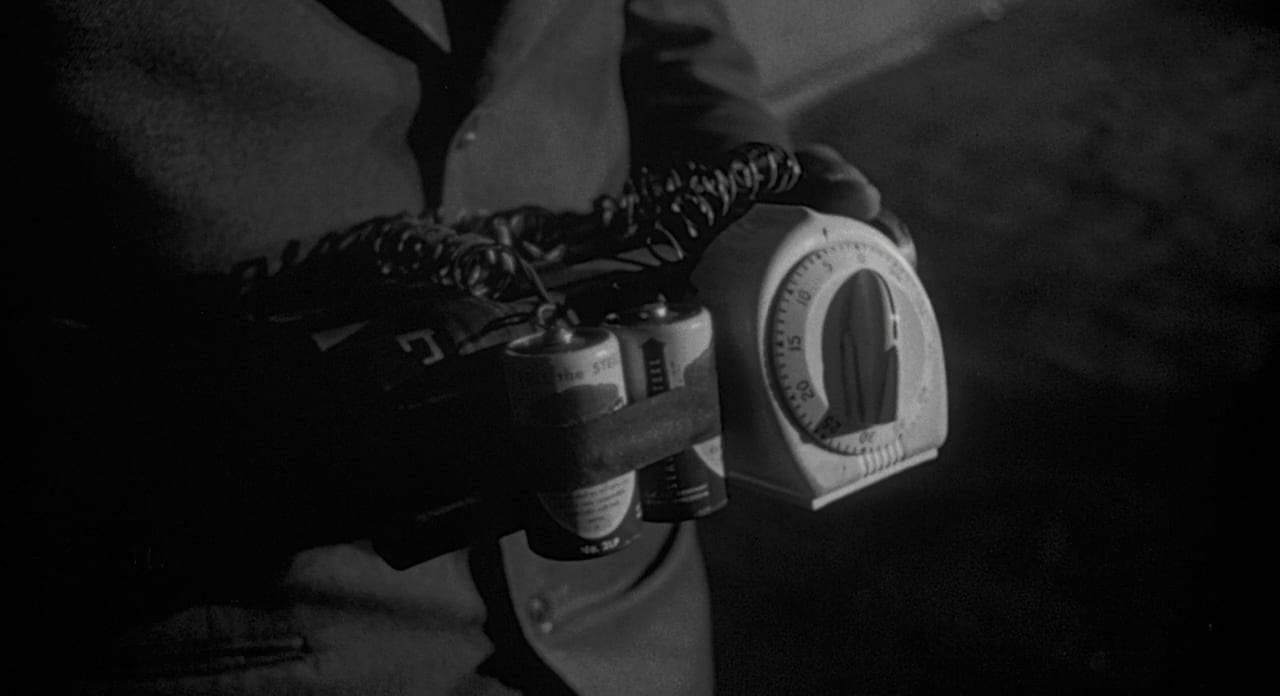

The picture’s most remarkable photographic feat is its opening scene, an unbroken 3 ¼-minute crane shot which ordinarily would have been composed of a series of separate shots. The action covers several blocks of downtown Venice from an amazing array of angles, including close-ups, low-tracking shots, very long shots and bird’s-eye views. It is further complicated by being elaborately night-lighted, and there is a lot of detail and activity on the border town street. Metty properly gave much of the credit for the virtuosity of this complex scene to camera operator Phil Lathrop, ASC, who soon became a distinguished director of photography in his own right. The camera seems to float through the action, gliding in all directions, without a glitch.

The sequence begins with a close-up of a time bomb in a man’s hands as the clock is being set. The camera swings up as the culprit looks down the street to see if anyone is coming, pulls back as the man runs to the right, and follows his shadow along a building wall to a Cadillac convertible parked behind the building. The man puts the bomb in the trunk and runs away as the car’s doomed passengers, Linnekar and Lita, emerge from the back door of a nightclub and climb into the vehicle. Pulling away from the camera, the car circles behind the building as the camera moves to a high angle to show it pulling out on the far side and turning right onto the street. The camera then races past and far ahead of the car, swooping down to eye level and turning back as the car moves toward the lens. Vargas and his wife cross the street in front of the car, and the camera moves close to follow them as they turn and walk ahead of the auto. The camera again moves ahead, to the American side of the checkpoint. The guard and the driver chat with Vargas, congratulating him for nabbing Grandi, while Lita complains that she hears a ticking sound. After the auto passes the Vargases, the camera moves in close and picks up their conversation as Mike says to his new bride, "Do you realize I haven’t kissed you in over an hour?" As they draw close, a terrific explosion occurs offscreen left. Only then is there a cut, to the Vargas’ view of the exploding convertible.

Equally elaborate and difficult, but on a much smaller scale, was the first scene that was filmed. Quinlan interrogates a suspect in the bombing incident in the youth’s tiny apartment, and plants dynamite to frame him. Heston recalls that cast members rehearsed during the night. In the morning, Welles and Metty had laid out "a master shot that covered the whole scene. It was a very complicated setup, with walls pulling out of the way as the camera moved from room to room [on a crab dolly], and four principal actors plus three or four bit-players working through the scene." This single take covers 12 pages of script in almost five minutes, creating the impression of about 60 setups, yet somehow never calls attention to itself.

In another unusual location shot, the camera follows Vargas and five men into a building, where the investigator puts the others and the viewer, personified by the camera aboard a tiny elevator. With its operator crouched in a corner, the camera records the shaky ride to the fifth floor, where Vargas is waiting.

One of the most violent and harrowing sequences in any film is the murder of Grandi in the cramped hotel room. The room is dark, with illumination from a flashing neon sign outside the window. Quinlan, a drunken ogre, pounces savagely on the much smaller Grandi, and the fight rages all around the unconscious Susan. Garotting his victim at last, Quinlan drapes the corpse over the brass bedstead. A "shock" scene comes later, when Susan awakes and we see, from her POV, an upside-down close-up of the dead man’s distorted face and bulging eyes.

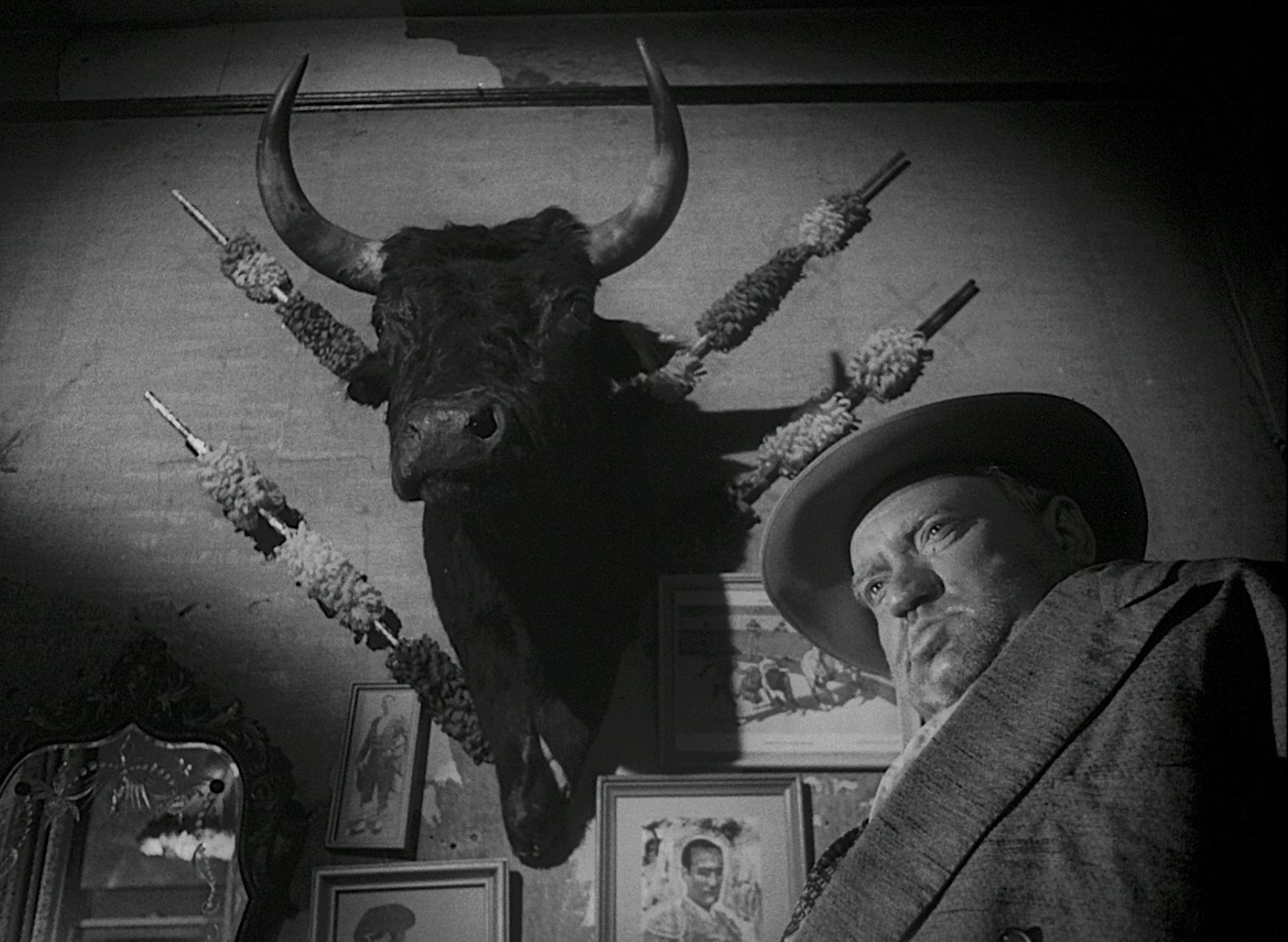

Most of the picture consists of hard-lit night scenes with jagged, opaque shadows and, toward the end, a few Dutch tilts. Day exteriors were done without fill lights. A few auto interiors were filmed on the process stage, but most were done on location with the camera mounted on the car. The hard-edged style is broken inside Tanya’s brothel, the only place where music is sweet, lighting is diffused, shadows are soft and camera angles are resolutely "normal."

Welles brought in several friends and associates for major supporting roles: Akim Tamiroff, Marlene Dietrich (whose personal fondness for Welles led her to join the cast as a "guest star"), Zsa Zsa Gabor (another "guest star"), Ray Collins and Harry Shannon. The latter pair respectively portray a D.A. and a police chief, back-slapping politicos who owe their popularity to Quinlan’s success at getting the goods on murderers.

Welles - his substantial bulk padded out grotesquely, eyes rheumy and heavily bagged, nose expanded is barely recognizable. Ever embarrassed about his small nose, Welles usually enlarged it with putty when performing. He makes Quinlan an almost completely despicable character, allowing only brief moments of sympathy such as when the police captain talks about the strangulation murder of his wife by a "half-breed" whom he was unable to bring to justice. (This is Quinlan’s rationale for his hatred of Mexicans and his practice of framing men he deems guilty but beyond the reach of the law.) Quinlan also seems more human during his scenes in Tanya’s brothel, where his venom subsides until he returns to the world outside.

Heston, his hair and skin darkened, is remarkable as the idealistic Mexican crime-fighter. His exchanges with Welles are sharp, as when he tells him that "I don’t think a policeman should work like a dog catcher." He swings into action convincingly when he tears into the Grandi boys and wrecks a saloon in the process. Leigh’s delicate beauty and vulnerability, combined with her witty handling of dialogue, set her well above the screen’s typical "ladies in distress."

Tamiroff is fine as Grandi, the vulgar narcotics kingpin whose dirty work is carried out by several vicious, leather-jacketed nephews. The character is both menacing and comical, qualities Tamiroff brought to many characterizations. A short, fat, wild-eyed schemer, he wears a heavy toupee that continually goes askew. His Moscow Art Theatre accent comes through amusingly on occasion, as when he addresses Susan as "Mrs. Wargas."

Dietrich, German accent notwithstanding, wears a black wig and smokes cigars as the hard-eyed madam of a bawdy house. She initially doesn’t recognize Quinlan when he wanders into her refuge, which he had frequented in better days. In most of her scenes, she seems dispassionate, coldly informing her former client, "You’re a mess, honey. You’d better lay off those candy bars," and then telling him, after consulting her tarot cards, "Your future is all used up." Yet at last, when she divines that Quinlan is in danger, she runs outside calling his name. She soon meets Schwartz, who is looking down at Quinlan’s corpse lying in a pool of oily water. "You really liked him, didn’t you?" he asks the madam. Without apparent emotion, she replies memorably, "The cop did, the one who killed him. He loved him. He was some kinda man. What does it matter what you say about people? Adios."

Gabor, speaking Hungarian-tinged English, looks glamorous in her brief scenes as proprietress of the Rancho Grande, where the murdered girl had been one of "20 Gorgeous Strippers." A number of other Welles chums also joined the cast for unbilled cameos. Billy House, a rotund old stage comedian, and Gus Schilling, one of Welles’s Mercury players and a star of Columbia two-reel comedies, play highway construction men. Mercedes McCambridge plays a sadistic lesbian in black leather who joins the boys converging on Janet Leigh in the motel while two girlfriends watch. Keenan Wynn and John Dierkes are just part of the ambiance. Joseph Cotten, as a grouchy, cigar-smoking medical examiner wearing a rube hat and toothbrush mustache, first appears at the scene of the bombing. When the police chief comments that Linnekar had the town in his pocket just an hour before being blown to smithereens, Cotten adds, "Now you could strain him through a sieve." When Vargas says he wants to meet Quinlan, Cotten growls, "No you don’t." Later, outside Susan’s jail cell, he rants about "articles of clothing, half-smoked reefers, needle marks you can smell the stuff on her."

More conspicuous is Dennis Weaver, then an obscure Universal contract player prior to his stardom on TV, who does an eccentric turn as the twitchy, half-witted night manager of the desert motel. A raw-nerved religious fanatic, woman-hater and shrieking coward, the character is fascinating but overly flamboyant.

Even among these performers, one man’s sincerity stands out. Joseph Calleia, a veteran actor from Malta, makes Menzies the most realistic and touching character in the film. Throughout the first three-quarters of the movie, he frisks around Quinlan like a faithful dog, barking at anyone who crosses his boss. It is heartbreaking to see his eyes well up as he watches Quinlan, influenced by Grandi, returning to the bottle after 12 years on the wagon. Even after he realizes his friend is a monster, Menzies tries to defend him, recalling how Quinlan once saved his life by taking a crippling bullet meant for him. When he realizes at last that he must betray his friend, he becomes a stricken man tormented beyond endurance. His agony is the true touchstone of the film.

Principal photography for Touch of Evil was completed in five weeks, on April 1, 1957, and Welles delivered a roughly edited cut the following month. The job of scoring the picture was assigned by musical director Joseph Gershenson to Henry Mancini, who at that time was one of the industry’s staff composers, working anonymously in the shadows of musical directors. Welles had requested "musical color" incorporating "Afro-Cuban rhythms" and "traditional Mexican music" mixed with contemporary rock music, most of it coming from onscreen sources such as jukeboxes, car radios, cheap gramophones, loudspeakers and a player piano. He wanted "sustained washes of sound rather than a tempestuous, melodramatic or operatic style of scoring."

Mancini responded with a score that is launched by brief, jarring chords over the studio logo, followed by a percussive melodic pattern overlying a strong bossa nova beat that pulses through the title sequence until the explosion. The "washes of sound" continue throughout, always rhythmic and often as purposefully unpleasant as the visuals. The one lyrical theme is "Pianola," piano roll music played in Tanya’s brothel, which leavens the few scenes that lend Quinlan a hint of humanity.

Welles insisted that the incidental music "should sound as bad" as it would in reality. Toward this end, music supposedly heard over outside speakers or in the motel was deliberately degraded by re-recording it from cheap playback units under similar conditions. Welles enjoyed bombarding his audiences with unpleasant sounds, which he often did in his Mercury Theatre radio broadcasts. (This writer, a former theater man, remembers customers complaining about the screeching bird in Citizen Kane, and the cracked record and persistently beeping telegraph in Journey into Fear.)

The striking Touch of Evil score propelled Mancini out of anonymity. One admirer of the music was producer-director Blake Edwards, who hired Mancini to compose jazz music for his new television series Peter Gunn (of which Lathrop would shoot 61 episodes). The show was a hit, due in large part to the music, which resulted in two best-selling RCA albums. The success of further Blake-Mancini collaborations, such as Mr. Lucky and the Pink Panther features, led to an extraordinary career for the young composer.

Welles originally cut Touch of Evil with editor Virgil Vogel. Dissatisfied with the result, Welles recut it completely with Aaron Stell, shuffling elements almost frantically, playing fast and loose with continuity and becoming increasingly unnerved. The continuity was rough-edged and non-linear, with cross-cutting almost as disorienting to audiences of that time as the labyrinthine pattern D. W. Griffith employed four decades earlier in Intolerance. Typically, Welles didn’t stick around for postproduction. He and Tamiroff headed for Mexico to work on a cinematic version of Don Quixote.

Later, Welles returned to screen the studio’s cut. Some material had been dropped and several brief transitional scenes were added to smooth the continuity. The lengthy opening shot had become a title sequence, with credits superimposed. The added scenes were directed and written by Harry Keller and filmed in "less than half a day," according to Heston, who adds that they "didn’t vastly enhance or hurt the film. They were there to help the progression of the story." Both Heston and Russell Metty stated that Welles’ concept was followed closely in the final cut and that Keller’s scenes did not replace any of Welles’ footage. Janet Leigh agrees, but believes that although "the changes weren’t blatant, unfortunately, they were just enough to take away the film’s edge."

After a preview, the picture was shortened by about one reel. It opened quietly in February of 1958, without a premiere or much promotion. Touch of Evil was a box-office flop, but a jury of international filmmakers awarded it the Grand Prix at the Brussels World’s Fair.

It was the last picture Welles directed in the United States.

Welles Gets His Say

On the same night Welles saw the studio’s cut of his film, he penned a 58-page memo detailing some 50 changes that he felt would improve the picture. For the most part this document is good-humored and friendly, although a bit of the heartbreak bleeds through. Several of the filmmaker’s suggestions were implemented, most were not.

Now, after 40 years, Touch of Evil has been recut, following Welles’s instructions to the letter. Sponsored by Universal and released by October Films, the new edition was produced by Rick Schmidlin and edited by Walter Murch, who earned an Oscar for his work on The English Patient. Bob O’Neil was in charge of picture restoration, while the soundtrack was restored under the supervision of Bill Varney, Universal vice president of sound operations and winner of Academy Awards for The Empire Strikes Back and Raiders of the Lost Ark.

Allan Daviau, ASC, who first read the Welles memo in the fall 1992 issue of Film Quarterly, credits UCLA Film Archives founder Bob Epstein with locating the missing Evil footage. The cinematographer recalls that in the mid-1980s, Epstein suspected that Universal may have had a print of the original Welles cut in their vaults. Requesting to screen every available print of the film, Epstein discovered a preview version of the picture, featuring the title-free opening shot and later-deleted scenes. This print supplied the footage that was required for the restoration, as per Welles’s memo. (Not incidentally, Daviau and friend Steven Spielberg had made a similar quest some years earlier, but had not found their Holy Grail.)

A new digital restoration process offered by Pacific Title Mirage was employed by O’Neil’s crew to repair film damage and decomposition in the source negatives. "One part looks as though the negative must have lain on the floor with people walking on it," O’Neal noted.

The serpentine opening crane shot is most strikingly altered by its return to Welles’ original concept. The overprinted titles of the earlier releases were an obstacle for anyone trying to concentrate on the picture and even more of an annoyance for those few patrons who actually try to read the credits. (To this day, titles continue to be dumped onto opening sequences, and it’s still a bad idea.) The restoration of the scene’s ambient sound effects adds immeasurably to the establishment of the border town’s vulgar atmosphere, and actually helps mold the characterizations of the actors. The only regrettable aspect of the redone sequence is the necessary loss of Mancini’s opening music. Film restoration, like the march of civilization, sometimes demands that we take one step back before we can move two steps forward.

Schmidlin had done several years of research before the picture went back to the cutting room. The editing team worked for two months, incorporating both the release negative and the print of the longer preview version. "The film not only plays beautifully but looks and sounds the way the master himself wanted it to," Schmidlin says. "That’s what people really want from this film, to see Orson Welles’ work as he’d planned it. Screening Touch of Evil at the Cannes Film Festival this past summer was a dream come true for me, and for international cinema, it’s an historic event."

Special thanks to Bison Archives for their help in supplying production photos for this article.

Touch of Evil was selected by ASC members as one of the 100 Milestone Films in Cinematography of the 20th Century.

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.

Access the every issue of AC and every story from more than the last 100 years with our Digital Edition + Archive subscription.