The Defiant Ones — Ultimate in Mood Photography

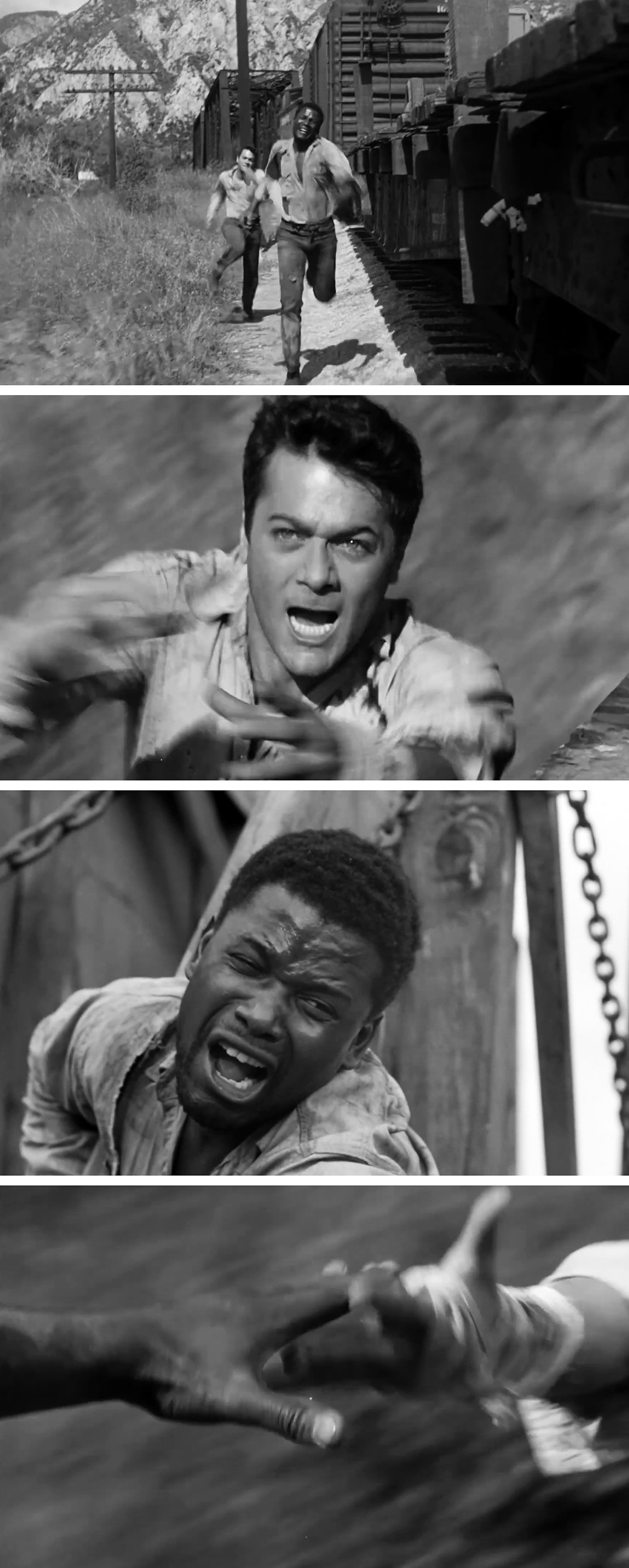

Adverse weather conditions were used to advantage to point up offbeat mood of dramatic escape from chaingang, photographed in black-and-white by Sam Leavitt, ASC.

This article originally appeared in AC Aug. 1958. The text is presented here as it was originally published.

Mood, in motion pictures, is a visual thing. It is something that is established by the photography and sustained by the photography. It comes through from the screen with the greatest impact when the director of photography has an innate feel for creating mood through artful lighting and camera angles. This, of course, is something which all veteran directors of photography have, each in varying degrees — a talent developed during many years of photographing motion pictures. But, as with any endeavor, now and then one stands out above all the rest.

In The Defiant Ones, being released this month, director of photography Sam Leavitt, ASC, demonstrates this talent in his photography of one of the best black-and-white pictures of the year. Low-key treatment begins with the initial scene and continues, with only slight and infrequent variations, almost to the very end.

In a way, photographing this off-beat picture was something of an artistic sacrifice for Leavitt, and at the same time, an extraordinary challenge, too. And one wonders if actually he did not profit by the overwhelming odds he faced during the filming of the picture — most of which was shot in extremes of cold, rain, and wind — so that in facing up to the challenge he brought about a superior photographic result. But despite all the back-breaking effort put into the camerawork, producer-director Stanley Kramer decided to tone down further in the printing the aspect of some of the scenes beyond what was possible to accomplish in the photography. Kramer’s aim was to add still further emphasis to the stark, cold and unfriendly atmosphere that prevails during much of the picture.

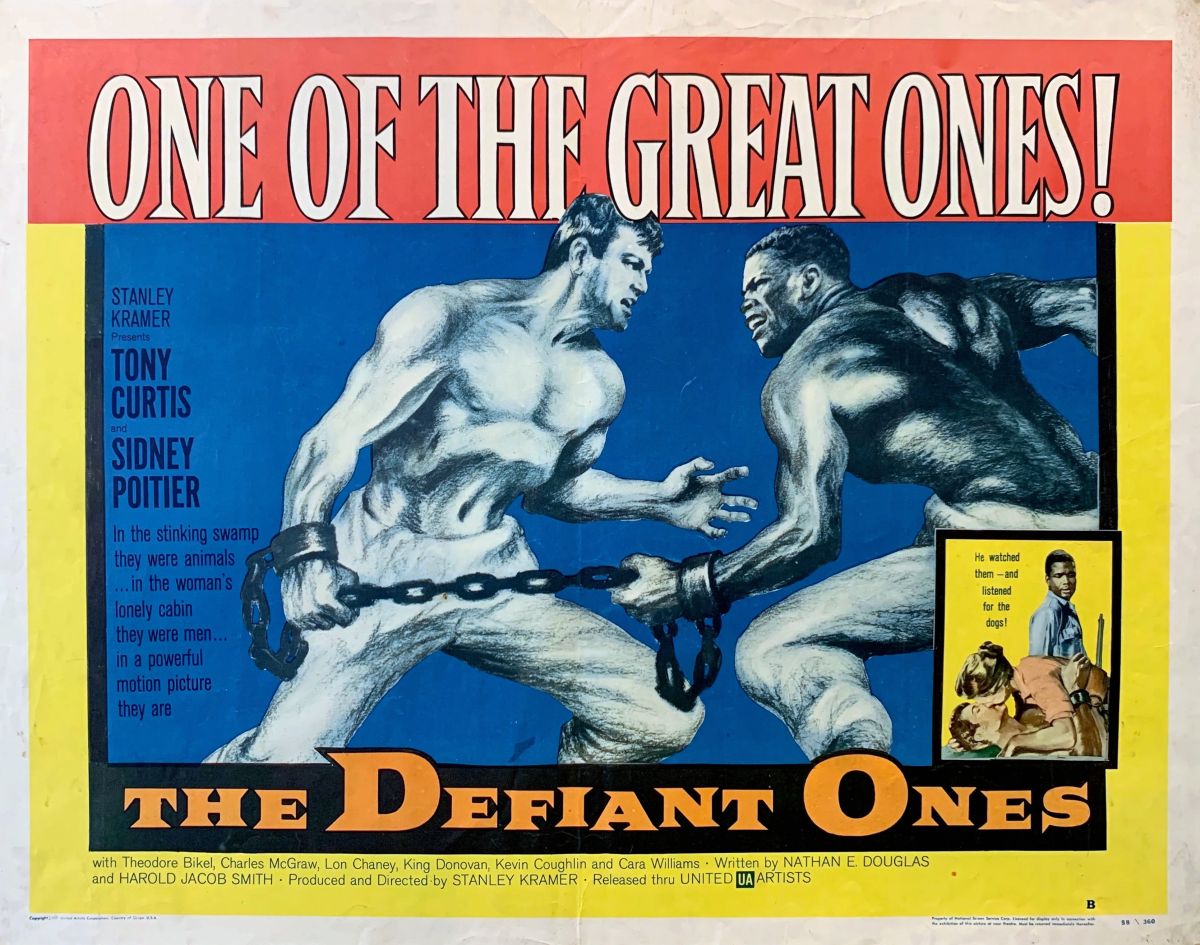

The Defiant Ones is a violent and uncompromising story about the defiance of youth and of the individual in our society and in all the world. Its principals, played by co-stars Tony Curtis and Sidney Poitier, are two fugitives from a chain gang, white and Negro, who hate one another’s color, but are shackled together as they attempt to escape. While it is basically the dramatic story of the savage experiences of two men “running scared,” whose mutual hatred is tempered by the realization that they must depend on one another to survive, The Defiant Ones boldly reflects the white-versus-Negro conflict.

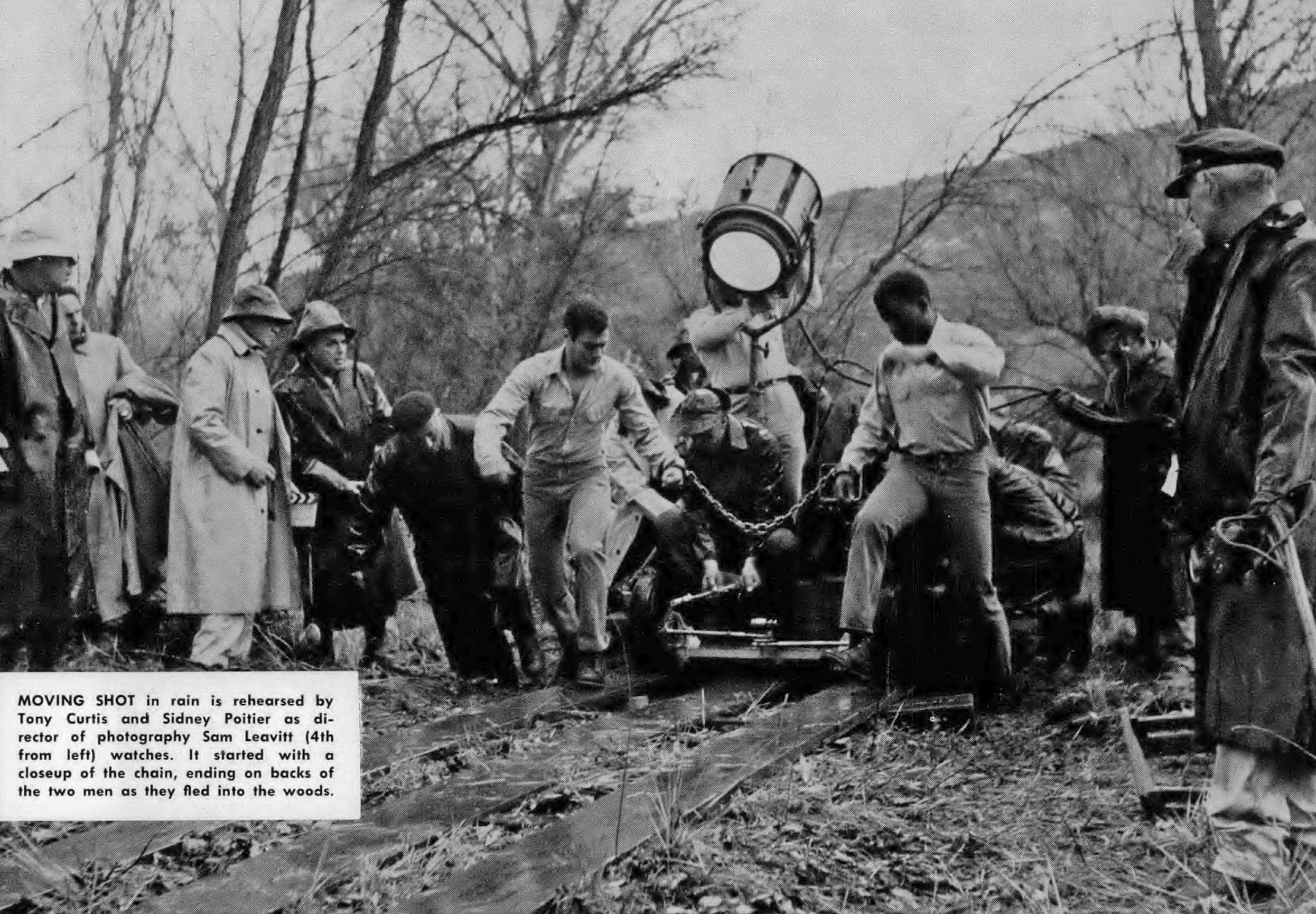

In photographing the picture, 80 percent of which was location exteriors, Leavitt and his crew, which included operator Al Myers and assistants Robert Hosler and Ralph Ash, took possibly the severest physical beating ever endured by a camera crew. Although the story is laid in a nondescript Southern U. S. locale, it was photographed entirely in Southern California, within a 225-mile radius of Hollywood. Shooting, which began in February, took place during the worst weather period of the California season. From a production standpoint, the weather was made to order, for much of the action detailed in the script takes place while it’s raining. The picture opens with a prison van transporting a load of manacled prisoners to a chain-gang location. The van collides with a produce truck in the blinding rain and Curtis and Poitier are thrown free and make their escape. In this brief opening sequence are some of the most effective night shots seen in black-and-white photography in a long time. The lighting is underplayed and highly effective in its naturalness. The incident appears with all the realism of a newsreel account of some important highway happening.

As dawn breaks — and this is the real thing — we see the manacled prisoners, now near exhaustion, still running in an effort to put time and space between them and their pursuers, who by now are assembled at the scene of the accident and awaiting arrival of bloodhounds before starting to track them down.

In the strange and trackless wilderness in which the escapees find themselves, the conflict between white and black smolders and occasionally bursts into flame, providing occasion for character-revealing studies of both men in sharply etched closeups. Here the challenge for Leavitt was keeping a proper exposure balance for the white man and the colored man appearing together in the scenes.

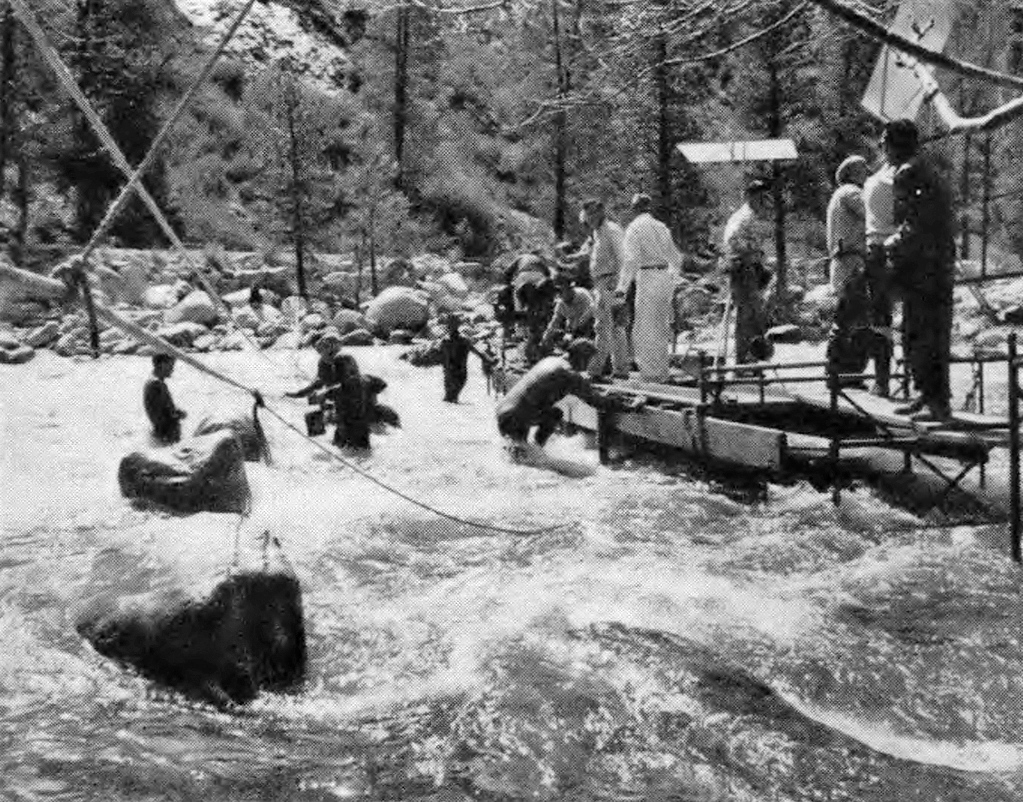

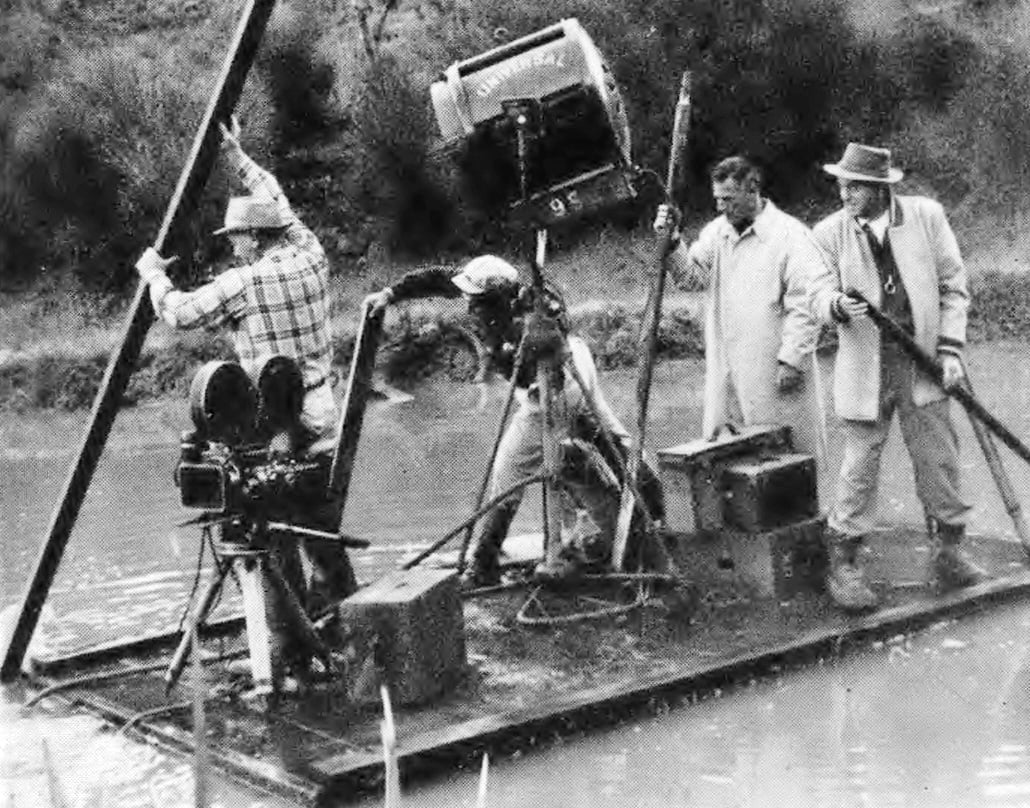

As the two men press on, they come to a turbulent stream. Crossing it provides the first great dramatic moments in the picture, as white-manacled-to-black inch their way through the swift current in an effort to reach the opposite shore. For these scenes, which were filmed on the Kern river in Central California, Leavitt had a long parallel built out into the water and extending almost half way across the stream. Dolly tracks were then laid so that the camera could follow the struggling escapees in vivid closeup as they moved precariously through the water.

Suddenly, one of the men loses his footing and the two are torn from a boulder where they had sought temporary refuge and are carried downstream. Ensuing shots — excellently photographed and skillfully edited — show the men struggling in the raging waters, tumbling over half-submerged boulders, then finally stopped by a tree trunk against which the two have been providently tossed.

Further on in their flight, the rain has increased to cloudburst proportions. As the men slodge along a road in ankle-deep mud, they suddenly hear a horse-drawn wagon approaching. To escape detection, the frantic prisoners jump into a clay pit, now partially filled with water, and remain submerged until the wagon passes. Their struggle to climb out of the pit is a classic in suspenseful movie making, if not a remarkable accomplishment in photography — done as it was in a simulated rainstorm with water everywhere but actually in the camera. The effectiveness of drab, flat photography is especially effective here, and at the same time the knack of maintaining normal, consistent exposure on the two men of opposite coloring is especially evident.

In their relentless flight, there are many interesting and character-revealing incidents, and through it all runs an incessant feeling of hatred between the two manacled men. Having threatened often to beat each other when they succeed in freeing themselves of the manacles, sheer exhaustion and mounting frustration finally brings about the oft-threatened physical conflict. Swinging hefty punches at each other, despite their chain shackle, they are locked in a death struggle in a thicket when a farm boy, hunting rabbits with a small rifle, comes upon them and orders them to put up their hands. The lad proves friendly and escorts the escapees to his home where his mother, deserted by her husband, struggles to make a living. She provides hammer and chisel to break their shackles and nurses Curtis’ wrist wounds, which have become seriously infected.

Here the photographic aspect brightens slightly in keeping with the change of mood, and there are deep accents in light and shadow in scenes in the cabin of Curtis and the woman.

At this point occurs one of the several outstanding photographic treatments in the picture. As Curtis, on a dingy cot in a corner of the one-room farmhouse, awakes from a coma, he starts talking to the woman who had remained beside him and nursed him during the night. His speech is a lengthy one — and the less-imaginative would have treated it in the all-too-familiar pattern of cuts and reverse-angle shots. Instead, the camera is centered in a tight two-shot on Curtis and the woman as he begins to talk; then, almost imperceptibly, it dollies toward them, pauses, then begins a slow ascent to a medium high-angle shot as the camera crane is gently elevated — the camera coming to a stop as Curtis ends his statement. Thus, what might have been a lengthy static shot (or a series of cuts) becomes a compelling, dramatic camera maneuver, subtley done, that effects the desired uninterrupted continuity in Curtis’ important statements at this point in the story.

Fades and dissolves have purposely been avoided throughout the picture in favor of straight cuts — except where a cut would prove too abrupt; in such cases, a transition is effected by having the player “walk into the camera’" to obliterate the scene, or the camera is moved forward to achieve the same effect.

It is in the closing scenes of the picture, where Curtis and Poitier — now freed of their shackles — seem close to their goal of freedom, that the dramatic potentials of imaginative photography are exemplified. After fleeing the farmhouse, the two men reach a nearby rail line where a freight approaches at moderate pace. After almost superhuman effort, the near-exhausted Poitier clambers aboard a flatcar. Curtis, who was wounded in the shoulder when the farm boy shot him following an argument with his mother, is weak from loss of blood. He nevertheless makes an heroic effort to get aboard the train.

Running alongside, Curtis vainly tries to grasp the outstretched hand of Poitier. Only inches separate their fingers for what seems an interminable interval of struggle. The train is picking up speed. You are right there on that flatcar watching helplessly as Curtis makes one supreme effort to grasp Poitier’s hand — so artfully and suspenseful is this sequence of scenes photographed and edited. You are dismayed when Curtis stumbles, just as he grips Poitier’s hand, and pulls him from the car, and the two roll down the embankment alongside the tracks, bringing to an end their one hope for freedom.

Limited space must limit description here of the excellent photography of this picture to the more or less outstanding sequences described above; nor have we related the picture’s entire story of the prisoners’ heroic flight toward freedom — crossing rivers, hiding in caves, sleeping in the open in a pouring rain, breaking into a store for food, being captured and nearly lynched and then jailed and released. But every single moment of this has been photographed with infinite care to heighten and sustain suspense as have few pictures in recent memory.

The picture was photographed on Eastman Plus-X, except for the night shots for which Tri-X was used. Maintaining a quality balance between shots made in rain or overcast with those filmed in bright sun was a major problem for director of photography Leavitt. “A considerable number of the exteriors were shot during actual rainstorms,’” said Leavitt, “so when the sun came out, we had to compensate for the change in light to maintain uniformity and sustain the mood. When we had to shoot in bright sun, we used a combination of fog and ND filters to tone down the result comparable to scenes that were filmed in rain or overcast.”

While Leavitt has photographed just about every type of motion picture that has been produced, from society dramas to rugged Westerns, and in both color and black-and-white, he seems to have unique talent for giving special photographic luster to the gutsy, down-beat type of story — of making the camera produce in dramatic emphasis what the players and dialogue and sound effects cannot do — give a picture visual impact. In this respect, The Defiant Ones is an outstanding triumph.

The Defiant Ones collected nine Academy Award nominations, leading to a win by Sam Leavitt for Best Black-and-White Cinematography. This would remain Leavitt's lone Oscar win, though he was later nominated in 1960 (for Anatomy of a Murder) and 1961 (Exodus).

The film also won Best Screenplay, for Harold Jacob Smith and Nedrick Young, though Young was blacklisted at the time and the Oscar went to his pseudonym “Nathan E. Douglas,” before eventually being properly restored in 1993 upon the request of his widow.

The other seven nominations were for Best Picture, Best Director (Kramer), Best Film Editing, Best Supporting Actor (Theodore Bikel), Best Supporting Actress (Cara Williams) and Best Actor nominations for both Curtis and Poitier — the first such nomination in history for an African-American leading man.

Aside from the leads, Williams and Bikel, the Defiant Ones cast also boasted Lon Chaney Jr., Little Rascals actor Carl "Alfalfa" Switzer in his final screen role, and one of the first roles for not-yet-famous Carroll O'Connor.

The film, now nearly 70 years old, remains relevant, thanks not only to the quality of the filmmaking, but as an important character-driven drama that helped launch Poitier’s career.

Click here for more archival stories from American Cinematographer.