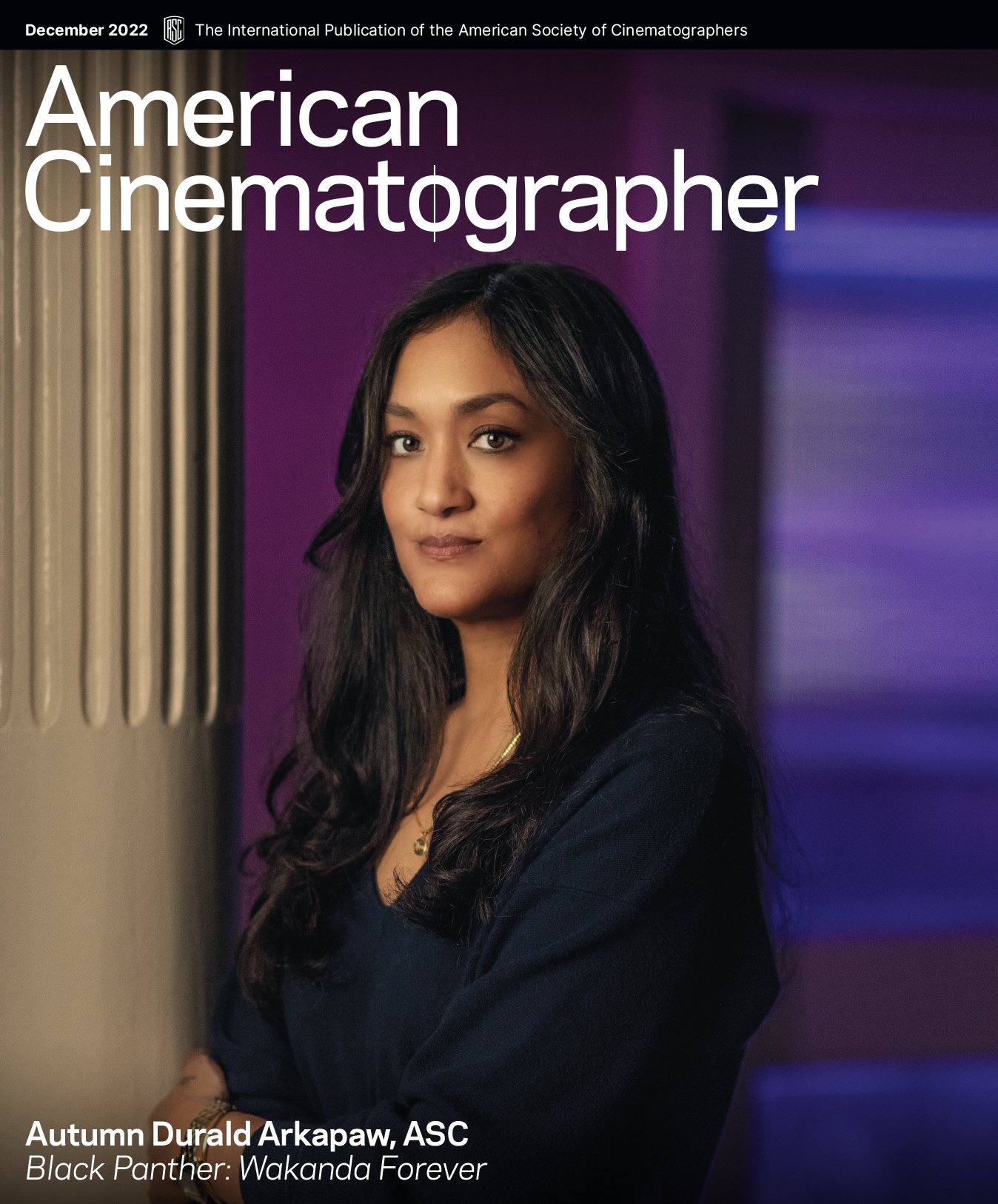

Full Picture: Autumn Durald Arkapaw, ASC

The new Society member reflects on the career arc that led her to Black Panther: Wakanda Forever.

The world that cinematographer Autumn Durald Arkapaw, ASC captures with her camera is not a small one. Her canvas is extensive — full of light, character and detail. She doesn’t shy away from production challenges, instead embracing the quirks and mathematics of squeeze factors, lighting management and set layouts. She wants her images to show the audience the full scope of the surrounding reality.

Her talent for capturing cinematic worlds has led her through a successful career, from independent and small studio films to the Marvel Cinematic Universe — for which she shot the streaming series Loki and this year’s highly anticipated Black Panther: Wakanda Forever. “I cut my teeth on indies for such a long time, and I don’t think I’d be able to do these bigger projects that I have now if I hadn’t played in that pool for so long,” she says. “It taught me so much about all the things you need to know when you finally begin to manage bigger budgets and bigger schedules and work with multiple departments.”

While she loves working on all types of films, she can’t help but be grateful to work on the Marvel projects because of the impact they have on broader culture. “I have a Loki hat and it’s my lucky hat. I wear it around town and people will start conversations with me. It’s really nice to be able to talk about the work and have people respond. People you don’t know get to tell you about how it made them feel or how exciting it was. It transports me to when I was a kid — I was also inspired by the television shows and movies that I saw.

Widescreen View

To give her frames the fullest portrait of the world, anamorphics are the go-to lenses in Durald’s kit. Her familiarity with the lenses’ various attributes reaches well beyond a decade, to when she first began using them as a student at AFI. She has employed them on productions of all sizes, from small indies like Teen Spirit to Loki to the latest MCU feature, Black Panther: Wakanda Forever. She tells AC that Wakanda Forever director-cowriter Ryan Coogler “laughs at me because I’m, like, anamorphic’s biggest fan.”

The format’s widescreen view is not the only reason she favors it. “There’s a nostalgic feeling you get from older glass, and that’s what I tend to shoot with,” Durald says. “The lenses I like are softer and have a dreamy quality.”

Early Influences

Coincidentally or not, nostalgia is a driving theme in the two films that sparked Durald to look beyond narrative and consider a movie’s visual aesthetics. When she first saw Broadway Danny Rose and Raging Bull in a film class, she was studying art history at Loyola Marymount University, planning to be a gallery curator or a photographer. The black-and-white cinematography of Gordon Willis, ASC and Michael Chapman, ASC spoke to her in a way other films had not. “All of a sudden, I was asking myself, ‘What does the cinematographer do?’” she recalls. “I decided to look into the job after that course. And I never saw any female cinematographers in the credits of the films I appreciated until I came across Ellen Kuras [ASC]’s name on Blow, a favorite film of mine. That day was so exciting for me — because I thought, ‘If there’s one, there can be another.’ After that, I took the career very seriously and decided it was something I really wanted to pursue.”

For a couple of years, Durald held a desk job in advertising while shooting short films with a camcorder on weekends. A friend noted her burgeoning interest and purchased her a UCLA Extension course in cinematography. Durald was hooked. She left advertising and applied to graduate programs in cinematography, one of which was AFI’s. She wasn’t accepted at first, but the head of the cinematography discipline, current ASC President Stephen Lighthill, advised her to get more experience and reapply. So she did. “I worked as an assistant on this amazing documentary TV series on the Sundance Channel, On the Road in America, and the cinematographer, Guy Livneh, was also a graduate of AFI,” she says. “We traveled across the United States, and I learned so much from him. He wrote one of my letters when I reapplied to AFI.”

Film-School Connections

Durald was accepted into AFI in 2006 and did everything she could to learn her trade, including shooting the micro-budget feature Macho during summer break. Her classmates proved to be an instrumental network. Following graduation, one of them gave Durald’s name to a young filmmaker who needed a camera test shot. That filmmaker was Gia Coppola, and she and Durald became professional colleagues and fast friends. In 2012, Durald shot Coppola’s first feature, Palo Alto, which played well on the festival circuit, garnered critical praise, and opened more doors.

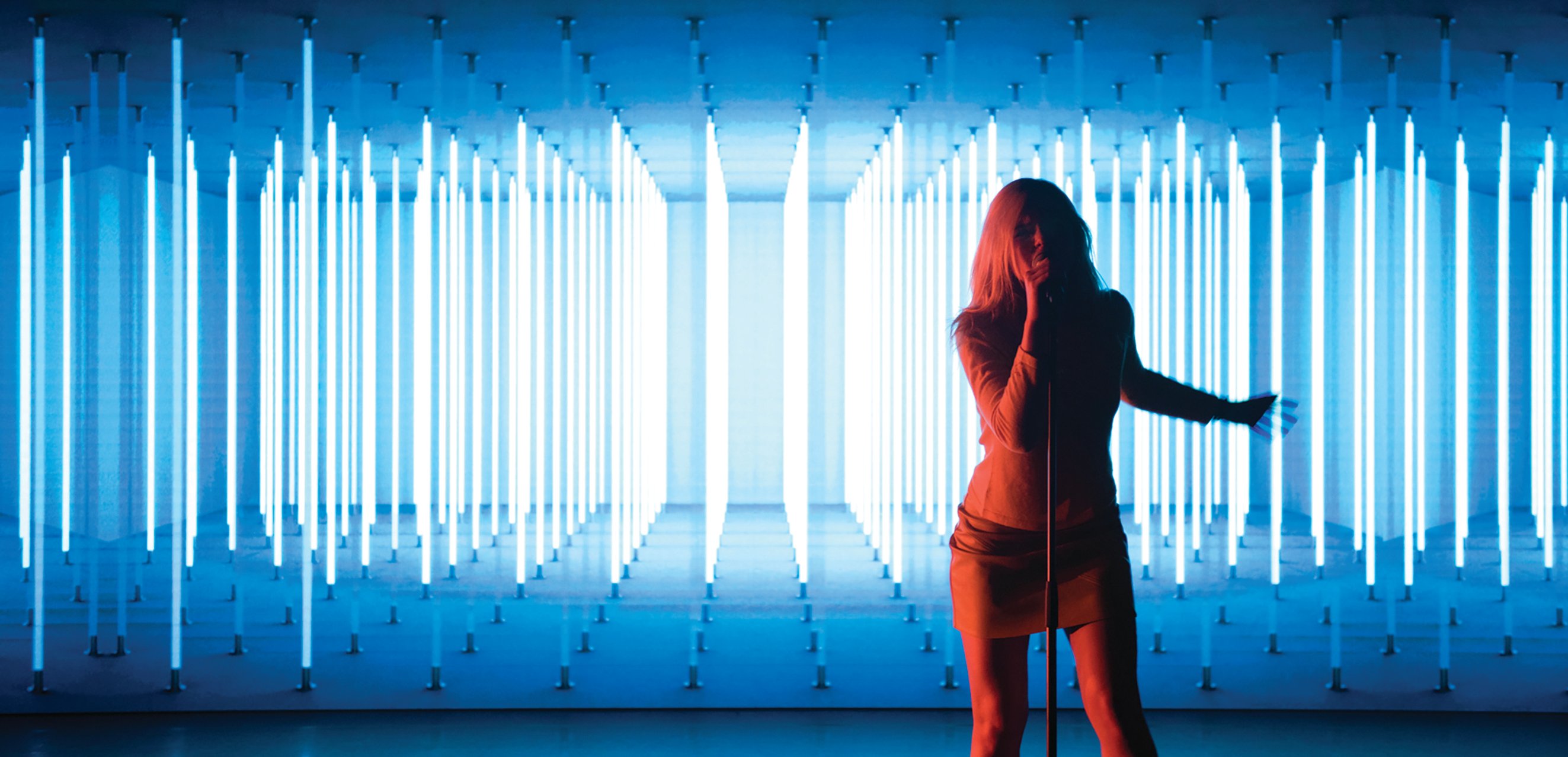

She was working steadily on commercials, shorts, documentaries and music videos (for bands such as Arcade Fire) when director-actor Max Minghella asked her to shoot his first feature, Teen Spirit (AC June ’19). “Teen Spirit was very important for me because I was again making a film with someone I considered a very close friend,” the cinematographer notes. “Max was very confident in my skills and trusting of me as a cinematographer. To have that support allowed me to be very creative and do my best work. And I learned a lot from Max — he’s very camera-driven and knows what he wants out of the shots.”

Teen Spirit required filming in large performance and concert venues, so Durald chose the C Series anamorphic primes from Panavision, a company she had developed a relationship with since her student days. She used the C Series lenses on her next feature, the YA romance The Sun Is Also a Star (AC June ’19), whose director, Ry Russo-Young, wanted to give New York the same sense of scope that Willis captured for Woody Allen’s Manhattan.

Attracting Attention

Durald’s work on these films brought her to the attention of Loki director Kate Herron. “I think Kate became familiar with my work because cinematographer Pip White, who is the wife of our producer on Loki, recommended I be added to their list of potential DPs,” Durald says. “That was amazing, because if that one person had not recommended me, maybe I wouldn’t be here today.”

Herron wanted Loki to look and feel like a feature film divided into six chapters, rather than a six-episode TV show. For inspiration, she and Durald drew from Brazil and Blade Runner — films that depicted entire worlds that seemed to exist outside the frame. To deliver that scope, Durald shot on the Sony Venice with Panavision’s T Series anamorphic lenses. “For me, choosing the glass is the first step,” she says. “The glass dictates so much of framing and how you approach blocking and your field of view.”

To bring out a dreamier feel that’s central to the C Series she loves, she had the lenses customized by Panavision’s Dan Sasaki, an ASC associate.

Loki was lauded for its visual storytelling and garnered Durald her first Primetime Emmy nomination. She is still humbled by it. “I never expected to do a big-budget project like Loki, and have it go so well,” she says.

Strong Roots

Last summer, Durald was invited to join the ranks of active membership in the ASC. Her sponsors were Society members Lighthill, James Laxton and James Whitaker.

Although she is now in demand for large-scale studio pictures, Durald’s approach continues to be rooted in the values that sustained her in her years shooting independent films. For her, friendship is foremost in filmmaking, and fostering a familial environment on set promotes creativity all around. “I started out in the indie world, shooting films that were made for no money,” she says. “It allowed me to be creatively free, because working with no resources — and making films with friends that care about you, support you and trust you — sets you off on a path to have confidence. As a cinematographer, you must have confidence in your ideas, in managing people and in directing your crew. Starting out on a smaller scale and working with friends was so important.”

Call of the Panther

A testament to the strong bonds Durald has forged over her career is that she was hired to shoot Wakanda Forever based on the recommendation of a friend, fellow AFI alumnus Rachel Morrison, ASC.

Morrison, director Ryan Coogler’s go-to cinematographer, had shot the first Black Panther, but was unavailable for the sequel because she was about to direct her first feature, Flint Strong. She recommended Durald.

It was not the first time a cinematographer had pointed Coogler toward her. When the director was searching for a cinematographer for Creed, his friend Bradford Young, ASC recommended Durald. “Bradford thought Autumn was the most talented cinematographer he knew who was coming up,” Coogler recalls. At the time, the studio didn’t think she had enough experience to shoot Creed, but Coogler continued to follow her career. And when Wakanda Forever came about, everything clicked.

“Ryan and I had a FaceTime, and I knew after that call that I wanted to be part of the project,” Durald says. “He’s a very special filmmaker and a remarkable individual. It was exciting because I was clearly going to be coming onto something that was already established, and friendships were established. I really wanted to bring something new to the project, but also just help to inspire the Black Panther team, because they had done something great together already.”

Themes and Glass

Coogler’s vision for Wakanda Forever had changed since the death of Black Panther lead actor Chadwick Boseman. “Ryan spoke a lot about grief, rebirth and redemption, and the unknown and the unknowable as it relates to grief,” Durald recalls. “On this film, highlighting the female characters and their relationships — relationships between mother and daughter — was really important to him. My past projects have had a lot of female protagonists, and I’m a mother as well, so I did have a strong perspective on that; it was lovely to talk to Ryan about how those relationships should shine.”

They also spoke about the science-fiction films Alien, The Abyss and the original Terminator — specifically their sense of grounded realism. Durald’s experience on Loki had taught her how to capture verisimilitude in the fantasy genre. “I want to do everything I can in-camera,” she says. “It’s important for me to work with VFX so that we’re doing as much in camera as we can to support the overall look in post.”

Coogler had never made a film shot in anamorphic before, and he decided the format would suit Wakanda Forever for unusual reasons. The director notes that after Boseman died, he began to fully conceive of “what kind of movie we were going to make. It became very clear that the film would deal with loss on a human level and what that feels like. The world looks and feels different after you experience profound loss, especially when it’s recent. You have this feeling of reality being a little bit warped, like [there’s] a fog over what you’re looking at in your day-to-day [life]. So, I thought the anamorphic quality would be good to embrace on a film like this.”

Durald believed again modifying the Panavision T Series set that she had used for Loki would best match Coogler’s vision. “I think Ryan appreciated the nostalgic, dreamy quality of the lenses,” she says. “He wanted some sequences to feel very dreamlike, like this dream where you have a lot of hope for the future. Also, with a lot of female characters, certain glass can be flattering and beautiful.”

Visual-Effects Collaboration

From the start, Durald worked closely with visual-effects supervisor Geoffrey Baumann and his team. She notes, “Our modified T Series have heavy aberrations, so they can be the visual-effects department’s worst nightmare! A lot of the time in films, you see the foreground plate that was shot in-camera, and then the background plate doesn’t have that same lens quality. We kind of broke new ground in coming together to try to make the CGI plates match the lenses and overall look of the film.

Durald, alongside Baumann’s team, performed rigorous testing during preproduction to give the visual-effects team the information they needed about how the lenses behaved. “They took it very seriously,” Durald says. “They built this huge document with our lens characteristics, how I like to light, and Ryan and my creative approach — and then had these one-hour seminars with various VFX vendors, going over the document and emphasizing, ‘It’s very important that we keep this vision consistent while doing post.’ To have a VFX team invested in your approach is beyond gratifying.”

Inspirations

At the time of this writing, Durald has yet to meet Ellen Kuras, but the ASC Lifetime Achievement Award honoree continues to serve as an inspiration to her — both on set and as a mentor to up-and-coming artists. “Speaking to the media about her career, she shows all the women and young girls who want to become a cinematographer that it’s possible, which is so important,” she says.

While making Wakanda Forever, Durald found herself becoming for others the role model that Kuras had been for her. “We’d be shooting on set for hours,” she says, “and I would have extras and PAs come up to me — women of color, who said, ‘I’ve never seen a woman of color in your position before.’ And they’d say, ‘Great job.’ That feels amazing. Ryan gave me this opportunity, but it is so much bigger than just shooting the film.”

She adds that when she teaches — whether during her first ASC Master Class session this past October or her returns to AFI to speak at women’s workshops and at cinematography classes — young women have approached her to express their appreciation. “They’ll look me in the eye and say, ‘Thank you for just going out there and trying to do this job, because now it’s encouraged me to do it.’ That, for me, is so rewarding.”

She believes her engagements with these classes should go beyond teaching camera and lighting techniques. “When I talk about this job. I talk about it in a broad sense,” she says. “I don’t just speak about going to school for cinematography or shooting films. There’s many other things I elaborate on, like how our job affects relationships, how it affects having and raising children, the travel involved, the stress involved. I try to give them a full picture, because it’s important as a cinematographer that I provide that clarity. I feel it’s my responsibility to speak up, because there aren’t many women shooting films at this budget and size. I feel privileged to be where I am and talk about my experience.

Tech Specs — Black Panther: Wakanda Forever

2.39:1 and 1.90:1

Cameras | Sony Venice

Lenses | Panavision T Series (customized), Ultra Panatar

Spotlight on Production Design

Hannah Beachler, the Oscar-winning production designer of Black Panther, who has worked on all of director Ryan Coogler’s features, has collaborated with a host of talented cinematographers over the course of her career, but none quite like Autumn Durald Arkapaw, ASC.

In Beachler’s opinion, Durald’s fresh perspective gave the Panther sequel Wakanda Forever what it needed to be both a worthy successor and a unique film in its own right. “Autumn shot differently than I was ever used to shooting with Ryan,” Beachler says. “He and I were both in awe of it.”

Coogler, she adds, “does tend to shoot tight. If you look at some of his films, it’s really about the humanity of people. He wants to capture that in his frames and on faces. It’s a lot like Fellini — it’s about the faces.”

Durald, however, leans in the other direction, preferring to capture the most expansive view she can. Her images in Wakanda Forever, therefore, tended to showcase — in detail — the hard work Beachler put into crafting her fantastical sets. “I really love Autumn’s style, because she shoots super wide,” Beachler says, adding with a laugh, “She’ll pull back and see the set — and what designer doesn’t love that?”

Durald’s methods also surprised Beachler at times. “Sometimes I’d walk in and there would be a bunch of [atmospheric haze], and I’d be thinking, ‘What?’” the production designer says. “Then she’d send me a bunch of stills, and they would be stunning. Stunning! I was speechless, and I’m not a speechless person.”

Another new experience: “Autumn would come to me at the beginning of the day, we’d give hugs and then we’d walk around the set. She would say, ‘What’s important for me to see? What part of the set tells the story for the scene?’ And we would talk about [those ideas]. That had never really happened before I worked with Autumn.”

— Michael Kogge