Event Horizon: Scare Tactics

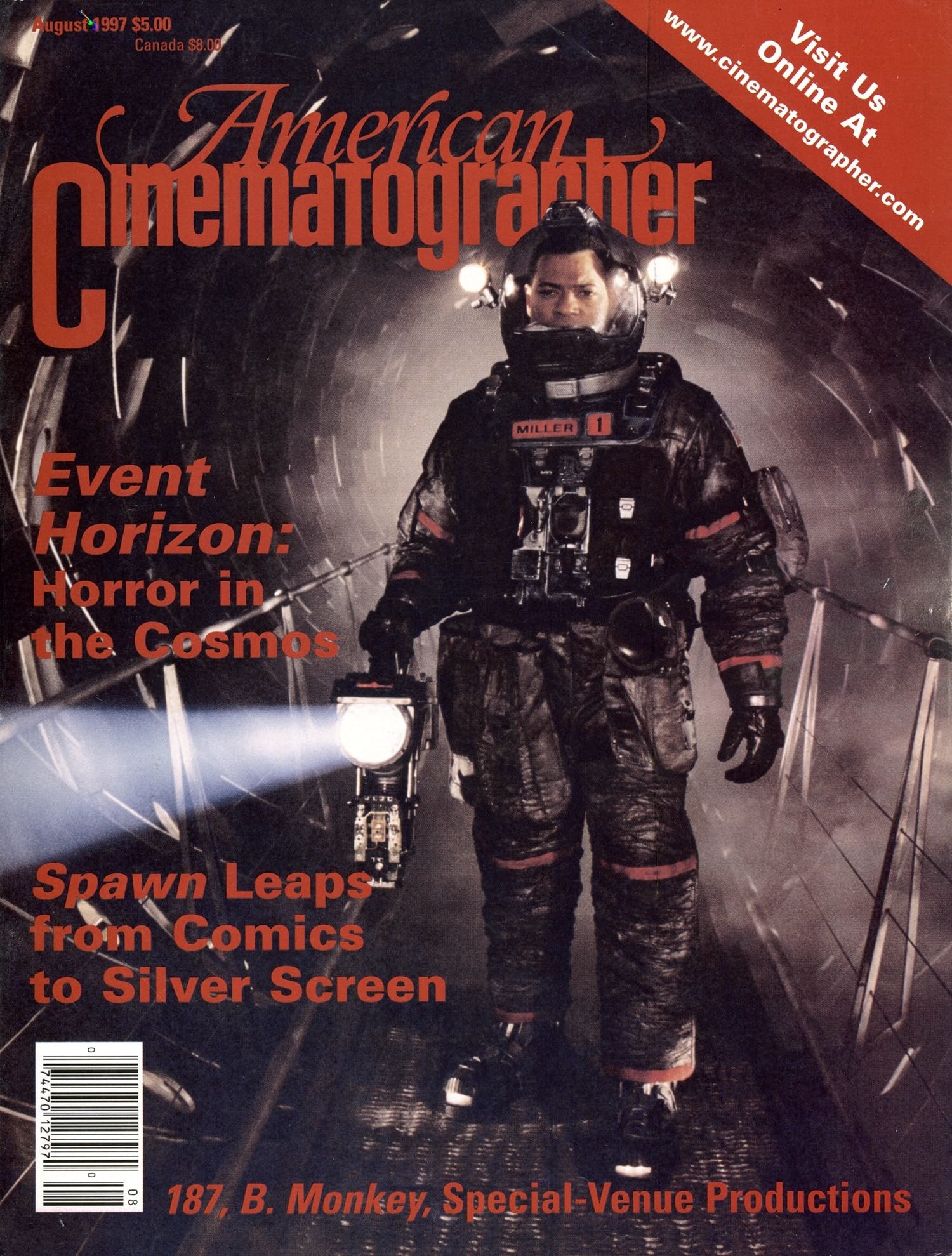

A blend of traditional and digital effects enhance the horror in this Gothic sci-fi suspense thriller.

Director Paul W.S. Anderson's hybrid science-fiction/horror film Event Horizon demanded 250-plus effects shots, running the gamut from the stars, planets and spacecraft of one genre to the abhorrent nightmare-inducing visions of the other. Pulling it all together was visual effects supervisor Richard Yuricich, ASC and visual effects producer Stuart McAra. The duo oversaw some 400 craftsmen and artists working in England, including CG experts at Cinesite London and Computer Film Company.

Yuricich's background in special effects dates back to the pioneering work he did with Douglas Trumbull on 2001: A Space Odyssey, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Star Trek— The Motion Picture and Blade Runner. (He was also the director of photography on Trumbull's Brainstorm.) But Yuricich is also known for his recent solo visual effects projects, Under Siege 2: Dark Territory (see AC Dec. 1995) and Mission: Impossible (AC Dec. '96). He decided to tackle Event Horizon because the project promised some completely unique effects challenges.

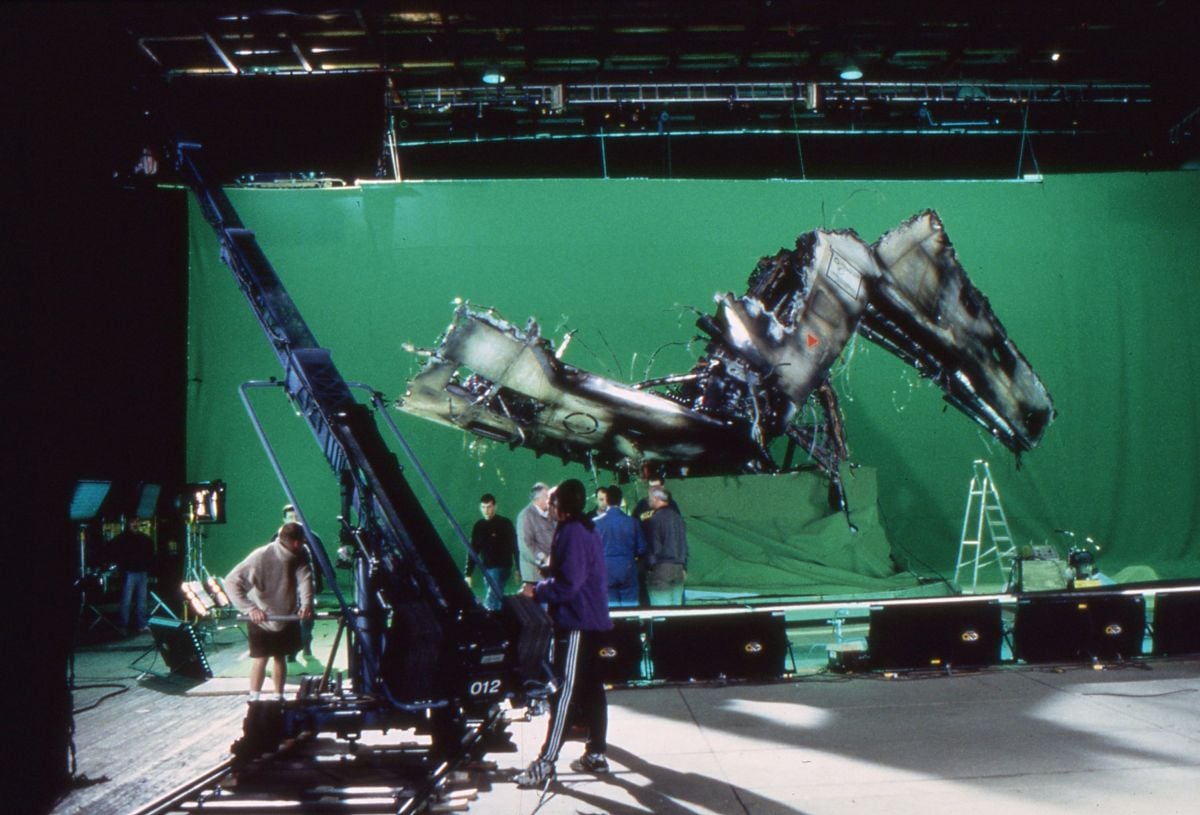

Both of the film's spaceships — the 250' Lewis & Clark and the mile-long Event Horizon — were created using models in several scales. There were 26 miniatures in all, ranging from a 1' version of the Lewis & Clark (which resembles a submarine crossed with an ambulance) to a 30'-long model of the Event Horizon. Yuricich notes, "Our problem was how to film something at that scale and get people to buy it. The answer was to put our 1' Lewis & Clark together with our 30' Event Horizon in the wide shots to establish the scale."

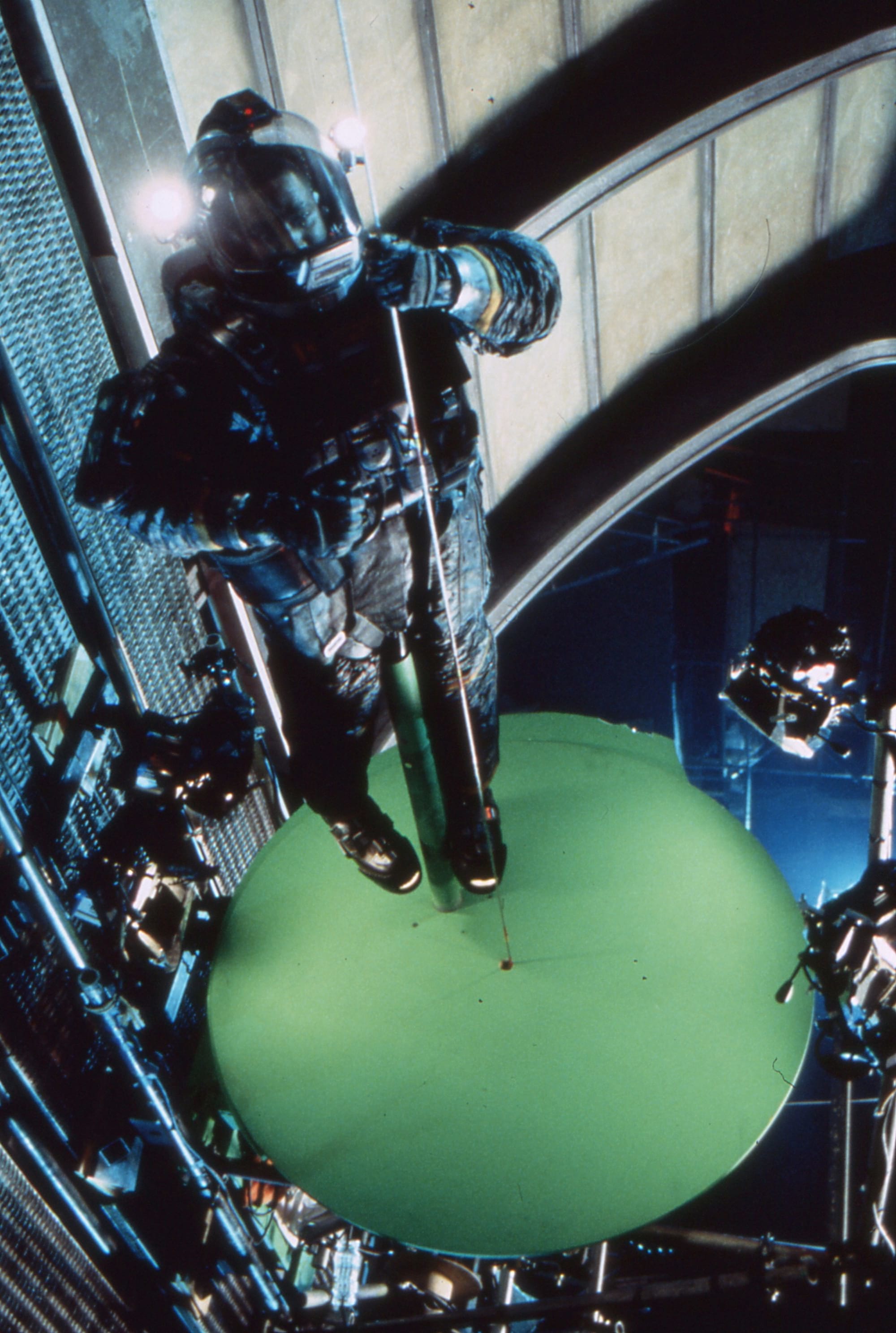

Scale issues of a different kind plagued Yuricich and company when a dynamic zero-gravity rescue sequence (dubbed "Miller's Crossing") was rewritten after the miniatures were constructed. In the scene, Captain Miller (Laurence Fishburne), who is doing a spacewalk on the tail of the Lewis & Clark, crosses to the Event Horizon in time to rescue the suitless Justin (Jack Noseworthy) as he erupts into space from an airlock. "In scale, Miller probably travels over a 300' area," Yuricich observes. "We did many cuts of him traversing the outside of the ship on the center section, which is between the five 3,000'-long corridors that connect the tail to the crossbeam containing the bridge and the three Containment chambers."

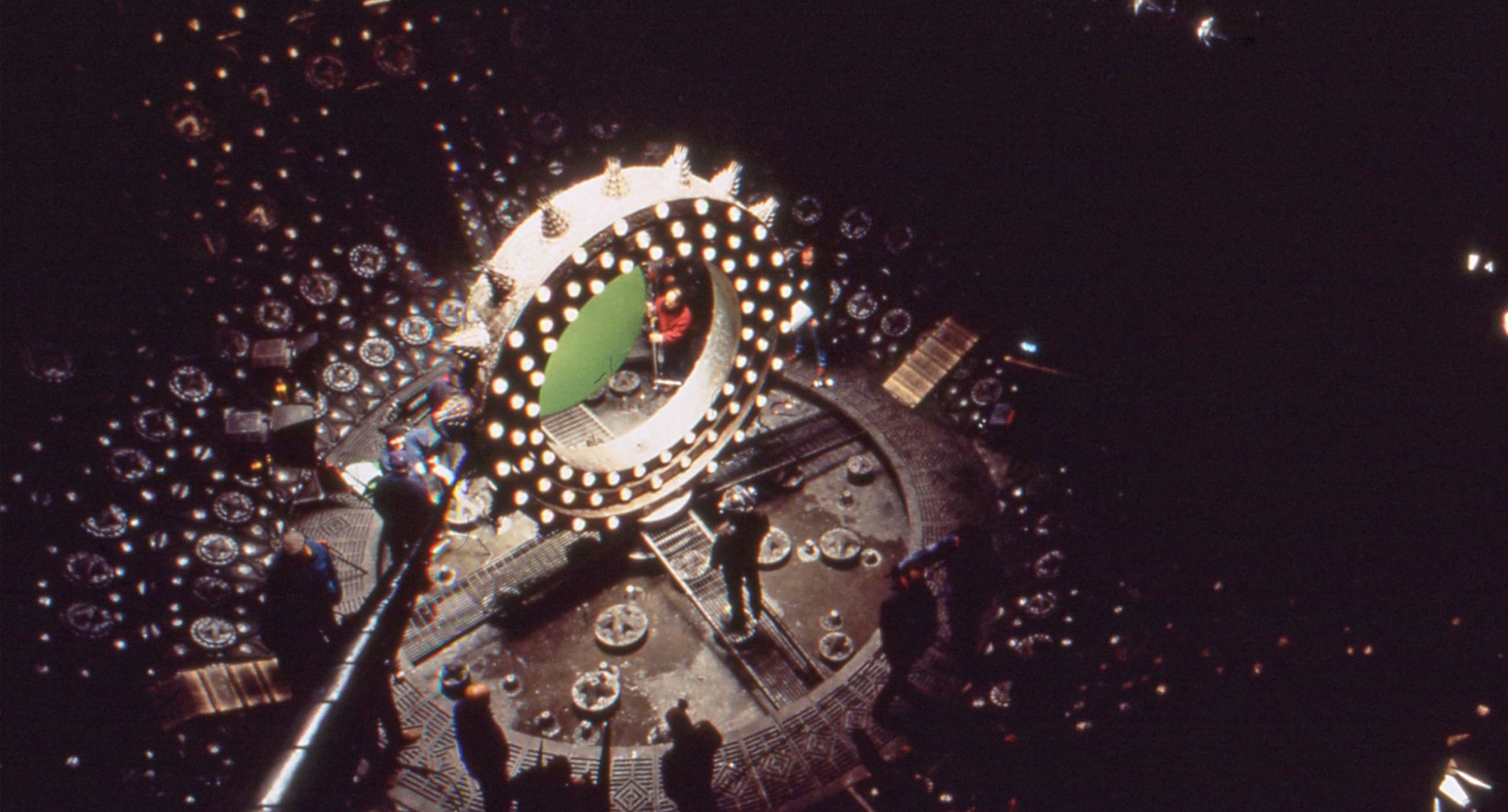

In the toughest of these shots, which were added at the last minute, the camera rotates within the ship's five columns as Miller rushes toward the airlock. After Fishburne (in his 65-pound spacesuit) was photographed against green-screen on a portion of the Event Horizon set, Yuricich had to duplicate those same moves on a 1/72-scale miniature of the ship's corridor section. He explains, "The live-action motion-control shot started with the camera upside-down and mounted on a Gazelle motion-control arm, going through about a 165-degree move with a wide-angle lens. We then repeated the same 165-degree rotation with the same Gazelle arm in the 1/72-scale miniature — but there was no room to get a camera in! The five corridors formed a pentagram shape, so when the camera was inside there, we had a couple of columns in our way. It was too cost-prohibitive to build another model, so we cut the miniature in half to allow the camera magazine to fit as it rotated. It was really an obstacle course, but [motion-control director of photography] David K. Stewart, ASC shot it in two passes. In the end, a live-action, 1:1 man appears to dive down through the columns and run on the inner surface of the five corridors. It's not real, but it looks cool."

through the First Containment.

Yuricich also helped to enhance the more horrifying aspects of the story, which occur after the Lewis & Clark crew boards the Event Horizon. The effects wizard worked in conjunction with both Pauline Fowler's Animated Extras and Bob Keen's Image Animation, using special makeup effects and animatronics to design nightmarish visions and ghastly demises. Makeup effects coordinator Joseph Ross served as go-between for the visual effects and prosthetic sides of the production.

In fact, Yuricich orchestrated such a horrible end for Lewis & Clark emergency technician Peters (Kathleen Quinlan) that the MPAA objected. He explains, "When the young lady falls to her death from the top of the fishbowl-shaped Second Containment into the metal grating below, I suggested that it should look like one of those gags where a body falls onto a car and you suck the roof down to show the impact. When the grating cracked up on impact, it was so dynamic it caused some problems with the ratings board."

The gag was achieved using a dummy of Quinlan and a full-body prosthetic worn by the actress. "We pre-rigged the stage floor so it would crack on impact when we dropped the dummy on a wire," Yuricich says. "Then, keeping the same camera position, we replaced the dummy with Kathleen."

But the live-action element was only the beginning for Yuricich's crew: "We did a stitchup and track in digital for the drop from the ceiling. We had to finish the Second Containment [in the computer] because even the 007 Stage, which was 65' high, wasn't large enough. Paul wanted the set to go about 10' higher, so we hung greenscreen and silly pieces of green paper between the rafters up above. Then Michelle Moen [Alien3] painted the elements for Computer Film Company to complete the ceiling. She's an oil-trained matte artist who was an assistant to my brother, [matte artist] Matthew Yuricich, before taking to the computer.

"Later, we digitally removed the wire and tracked Kathleen Quinlan's face onto the dummy. On set, we put her on a stretcher, and filmed her face as we raised her up through the actual stage lighting. That took five minutes. It was very low-tech, but it gave us an excellent 2-D reference for re-creating the lighting on her face digitally."

An even more involved digital tracking job was done to enhance the sequence in which Weir (Sam Neill) blinds himself. Although audiences are spared the actual eye-gouging experience, Neill goes through much of the film eyeless, courtesy of Bob Keen's prosthetic makeup and Yuricich's digital sockets. "We had Image Animation drill little holes in the center of each eye in the fleshy, bloody prosthetic device attached to Sam's face. Then we added a white circle, like a bullseye target, around each hole, and those were the tracking points. At Cinesite, we built a little 3-D CG model of a head with no eyes in it, and generated a fleshy eye-socket with a bit of fat tissue and little veins. Once we knew the interocular distance between Sam Neill's eyes, Cinesite could easily track our digital makeup to those little white bullseyes on the prosthetic. In the end, the eyes look gouged out and you can see into his head. Sam performed with an approximately 120-degree field of view while wearing the eye-socket appliances."

Another remarkable "vision" was the Burning Man, a haunting specter from Captain Miller's past. Originally, Anderson, Yuricich and [motion-control and systems supervisor] Mark Weingartner planned to use an elaborate, £60,000 robot to achieve the effect of a character whose epidermal layer was forever on fire. But after some budgetary belt-tightening, they were left with £5,000. "Image Animation built a mechanical man that was moved with strings and sticks, which we covered with fabric and then burned to make elements," Yuricich says. "We burned the body in sections, and then applied those pieces digitally to an actor in a burn makeup so the character wouldn't look like a flaming matchstick. We had various layers of flame. We also did a shot of the Burning Man walking in a tank of water, using robot legs. The element photography for this sequence was executed by Weingartner and his crew. We did multiple passes with the tank, the legs and some steam. He's only on for a few frames, so it looks pretty cool. It was 50 percent of the original plan, but it worked."

You'll find our complete story on the film’s cinematography by Adrian Biddle, BSC here — featuring director Paul W.S. Anderson.