Unearthly Terrors: Event Horizon

Director Paul W.S. Anderson and cinematographer Adrian Biddle, BSC enter the darkest depths of space.

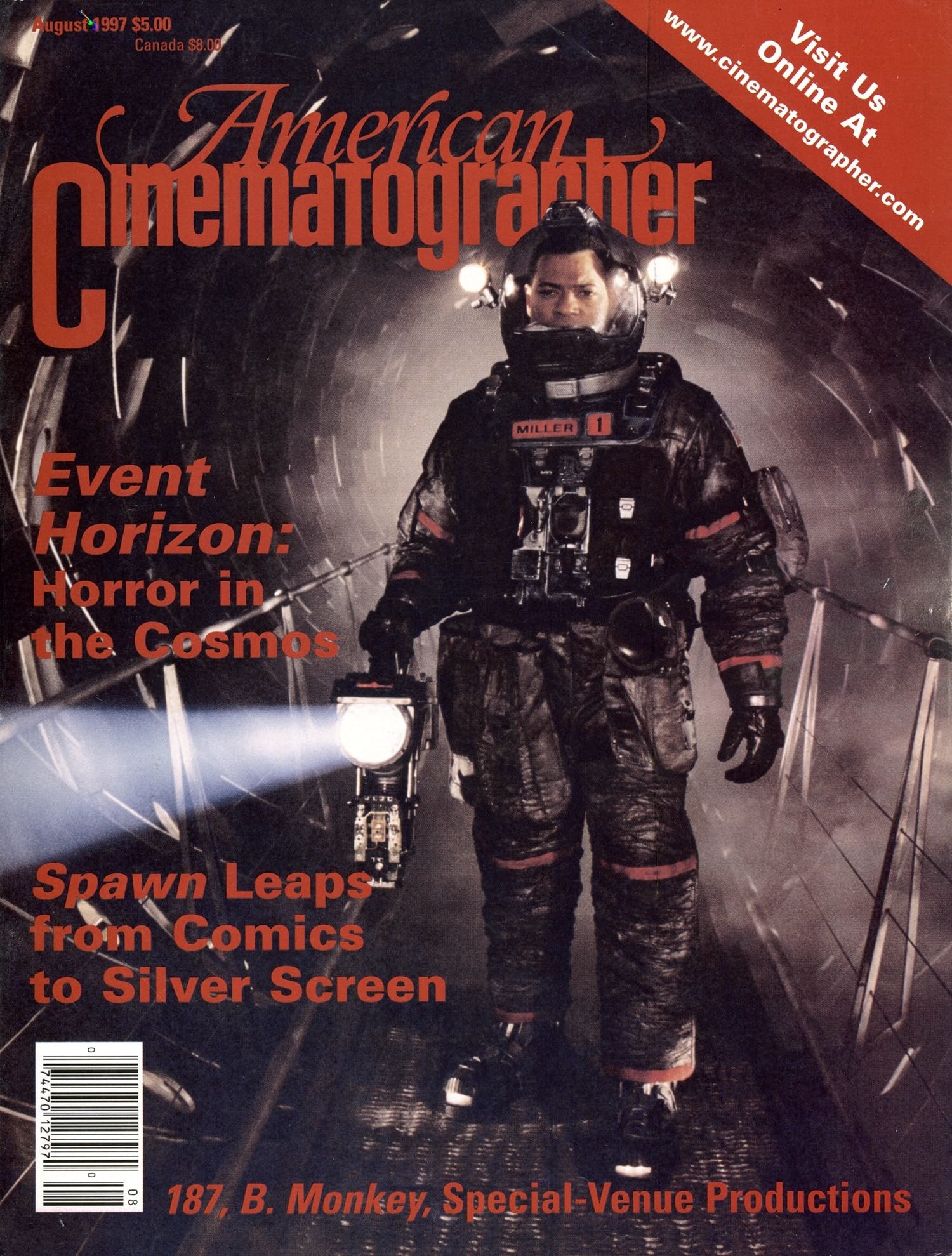

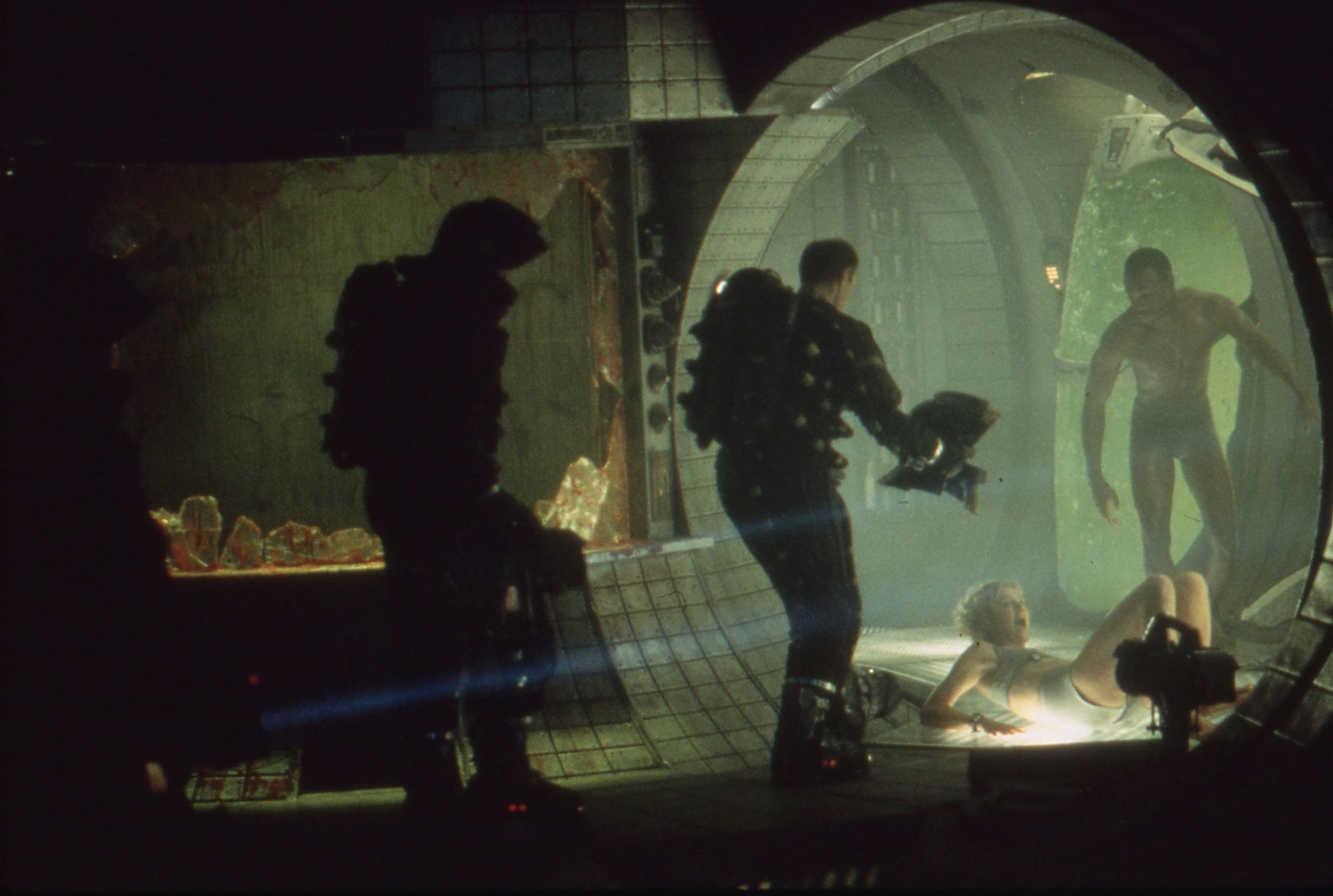

Quinlan) explore the main access corridor of the Event Horizon. Note supplemental lighting built into the set and costumes.

In astronomer's lingo, an “event horizon” is the point at which light and matter are ensnared by the immense gravitational field of a black hole, the remnants of a collapsed star. Scientists and science-fiction writers alike have postulated that black holes could possibly be portals to a distant galaxy, a parallel universe, or perhaps even Heaven or Hell.

In British director Paul W.S. Anderson's sci-fi horror film Event Horizon, this astral phenomenon also provides the name of a prototype starship powered by the energy of a black hole. After a seven-year disappearance, the ship has mysteriously rematerialized in orbit over the planet Neptune. A rescue mission mounted from a salvage ship — the Lewis & Clark — reveals that the derelict vessel has been ravaged by a malevolent presence whose origins date back to the Earth's Middle Ages.

This quasi-mystical plot provides the perfect backdrop for grim episodes of Gothic space horror. Director Anderson offers, "Event Horizon has a lot more in common with The Haunting or The Amityville Horror than The Black Hole. This film is about spacemen in the future who come face to face with a very medieval kind of evil in the far-flung reaches of our solar system. If you replaced The Shining's Overlook Hotel with a labyrinthine spaceship orbiting Neptune, you'd have the basic premise. It's a great bonus that the story is set on a giant spaceship, but we're not making any bones about it — we're out to scare and revolt people like they did in the good old days! We don't want any of this namby-pamby postmodern horror attitude, we just want people to jump off their seats. I wanted to make the kind of frightening horror movie that I loved as kid, like Alien."

Anderson's previous pictures — the $3 million independent cult film Shopping (1993) and the $23 million action-effects extravaganza Mortal Kombat (1995) — proved that he could milk maximum impact from frugal financing. Event Horizon's budget of $70 million offered considerably more breathing room, but still proved to be a daunting project. Anderson therefore entrusted its look to some of the business' top talent, including cinematographer Adrian Biddle, BSC and visual effects supervisor Richard Yuricich, ASC. "I think both Adrian and Richard are pretty sick individuals," Anderson opines with a chuckle, recalling a sequence in which one Lewis & Clark crew member gouges out his own eyes. "Richard was suggesting things like, 'He could sew his eyes back up again and we could do it in CG!' I'd reply, 'I'm a hardened horror fan, but even I don't want to see that!' Then Adrian would say, 'If I put a light over here, we could get more light into the empty holes of his eye sockets.' They definitely got into the spirit of the film."

Adrian Biddle has spent much of his career realizing fantastic yet believable milieus. In his early days as a camera assistant, he donned a pair of skis to shoot the famed toboggan chase in the James Bond adventure On Her Majesty's Secret Service. He also did some striking underwater work on Captain Nemo and the Underwater City. Biddle then served as a focus puller on director Ridley Scott's first two features — The Duellists (shot by Frank Tidy, BSC) and Alien (shot by Derek Vanlint, CSC).

Biddle's subsequent TV commercial work for Scott and other filmmakers netted him two Minerves prizes and a British Designers and Art Directors Guild Award for Outstanding Cinematography. He later served as director of photography on Scott's films Thelma & Louise (for which he earned an Academy Award nomination) and 1492 — Conquest of Paradise (see AC Oct. 1992). He has also served as director of photography on Aliens, The Princess Bride, Willow and Judge Dredd.

Having photographed so many genre films, the cinematographer concedes that devising a unique approach can be difficult: "A lot of it is done in conjunction with the director and the production designer. On Event Horizon, I was fortunate to be working with a director like Paul Anderson and a production designer like Joseph Bennett [Jude, Backbeat, Dust Devil, Hardware]. They really have a feel for these things. We went for more of a Gothic approach inside the Event Horizon ship, which has all of these crosses and objects of that nature within it."

When it first appears onscreen, the Event Horizon craft itself resembles a giant crucifix hovering over the surface of Neptune. "The spaceship was built on a cruciform, like all cathedrals are," Anderson explains. "We began the design process by literally scanning [photos of] the Notre-Dame Cathedral into the computer and then constructing the Event Horizon out of those Gothic elements. For example, the big thruster engines are an adaptation of the Notre Dame towers, repositioned on their sides. A lot of the iron and steel work of the superstructure is based on the cathedral's stained-glass windows. The ship also has a lot of triptych windows and big recessed crosses.

"When Adrian and I first sat down, we said, 'Let's do something completely different,"' says Anderson. "Since we were going into outer space, I felt we had to have a really strong design concept; otherwise Event Horizon would have ended up looking like [a bunch of] other movies cobbled together. We spent a lot of time coming up with a design concept, which we called 'techno-Medieval.' When the lights are on, everything looks very technological and very spaceship-like. But when the lights go off and the haunting begins, you start looking at the shapes, and the architecture is actually very medieval. We extended that techno-Medieval design idea into as many aspects of the picture's look as possible, without rubbing the audience's nose in it."

Beyond this hybrid production design, Biddle and Anderson struck upon the idea of using colored gels, a tactic not typically employed in films with such bilious subject matter. In moments of maniacal hysteria, for example, the spaceship's interior seems to come to life as a blood-like substance courses from the walls. Notes Biddle, "I used some sepia brown coming up from the floor to make viewers uncomfortable on the ship, as well as flashes of red. I also used a lot of green. Cinematographers generally shy away from green, because it's not very pleasant, but on Event Horizon I used gels to produce that nasty, horrible green you get from fluorescents when they're not corrected [for color temperature]. If you're in an underground car park, the fluorescents make you feel uncomfortable. I was going for that kind of an effect, to convey the idea that something not very good is lurking in the ship."

When Anderson first met with Biddle, the director showed him several improperly balanced photographs of a rock 'n' roll band standing in a corridor lit by fluorescent lights. The images had all gone a ghastly green. "It was like mistake-green," says Anderson with a laugh, "and I said to Adrian, 'That's exactly the color we want.' On Mortal Kombat, [director of photography] John Leonetti [ASC] and I really raided the lighting truck for gels that nobody else ever used — deep purples, shades like that. Adrian and I tried to do the same thing on this movie. We wanted unpleasant colors that would really unsettle people and make them feel a little ill and queasy. Adrian had just come off of 202 Dalmatians, and our attitude was, 'Enough of the cute little puppies — let's string a few of them up!"'

Biddle framed Event Horizon in widescreen anamorphic with Panavision equipment, just as he had done on 1492 and Willow. In an unusual move, the cinematographer photographed the entire film on Eastman Kodak's 500 ASA 5279 Vision stock, which he began using last summer, midway through production of director Neil Jordan's upcoming film The Butcher Boy. "The 79 was perfect for Event Horizon, because I get better blacks with it than I do with 5245 or 96," he says. "The 79 can be very forgiving in the dark. And in anamorphic, I'd rather go for a bit more f-stop to bring the quality up and get finer grain."

T. Jones) are rescued by a search party - "If you're in an underground car park, the fluorescents make you feel uncomfortable. I was going for that kind of an effect, to convey the idea that something not very good is lurking in the ship."

The interiors of the Event Horizon spacecraft filled most of seven soundstages at England's Pinewood Studios, including its vast 007 Stage. These massive sets would appear to offer unlimited directorial possibilities, but Anderson's insistence upon bizarre interior designs created a fair share of cinematographic constraints. In defending that tack, Anderson notes, "Whenever people build sets, they always tend to look like square boxes. It would have been easier to build sets with flat floors and flat walls to give ourselves lots of room for the camera, monitors and sound equipment, but it wouldn't necessarily have looked the most interesting. I wanted to get away from that 'big room' feel by building sets that were very different, using visually striking, interesting shapes. By doing that, of course, we actually made things more difficult for ourselves. We tried to get Adrian involved as soon as possible [in the design of the sets], since I knew they would be difficult to shoot in."

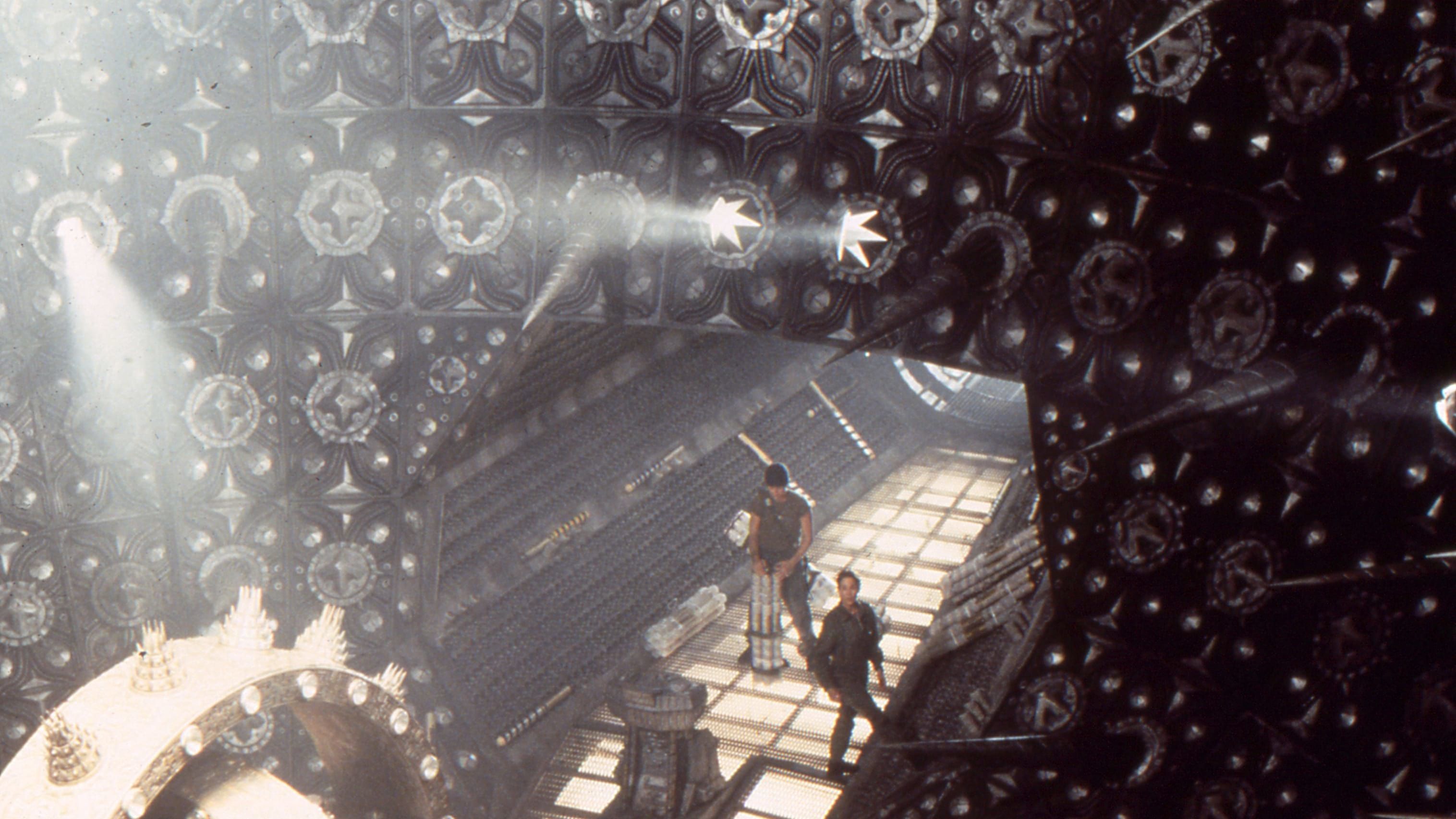

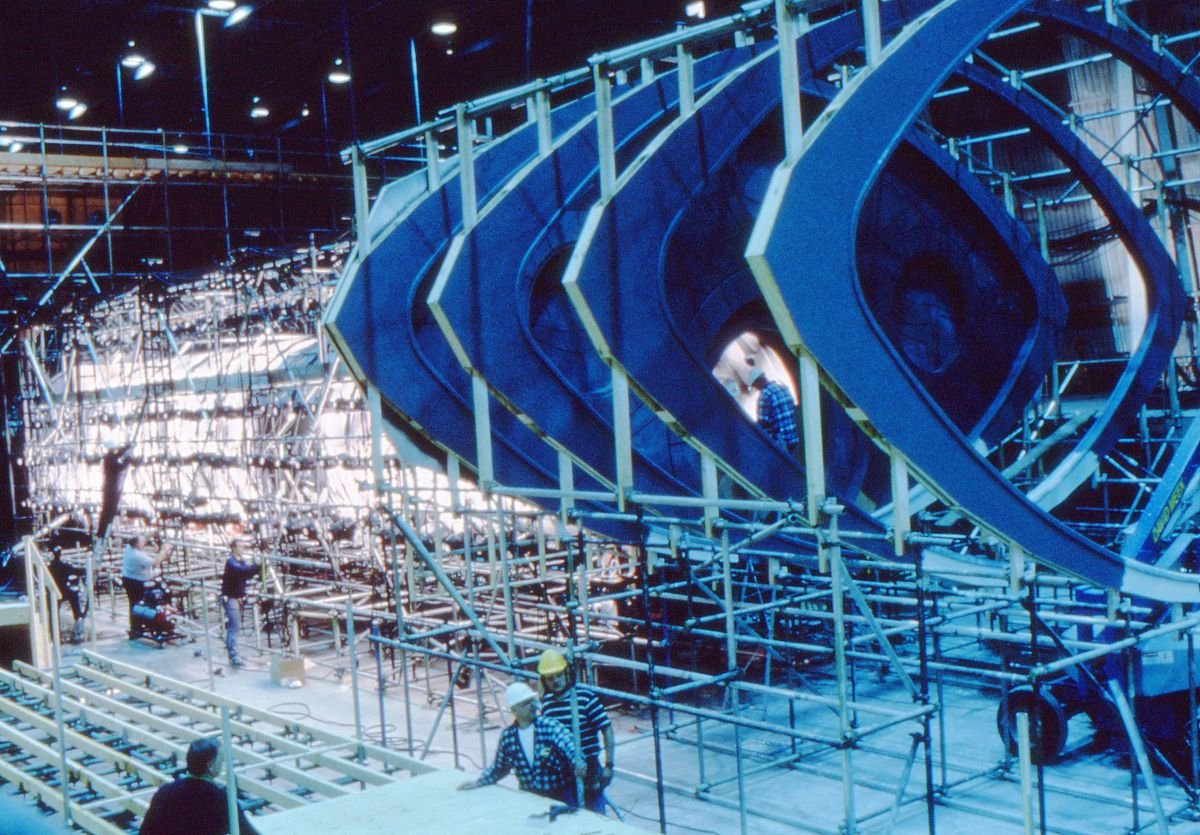

“One of the larger sets was a vast, elliptical-shaped corridor with a ceiling formed from massive ribs that resembled those of a whale.”

The colossal 007 Stage — the biggest silent stage in Europe — housed the Event Horizon's core, comprising three "Containments" that harnessed the black hole's energy. The sets consisted of the First Containment (a rotating corridor) connected directly with the Second Containment (a large, bowl-shaped room) which itself housed the Third Containment (a gyrosphere of spinning lights encompassing the black hole itself).

Each Containment presented unique cinematographic challenges. "The First Containment was a 50'-long tube that actually rotated, so the only bit that wasn't moving was this really thin walkway that ran down the middle of it," Anderson says. "The whole thing was like one of those turbines in a carnival's 'House of Fun,' where you walk through and fall over because you lose all sense of balance. The only place to put the camera was on the walkway, so we built dolly track into it in a discreet way, which allowed us to track down the length of that tube."

“"We shot several sequences that involved the tunnel. That set was one piece, and the whole thing revolved 360 degrees, so it was a big challenge to light.”

This Containment's dark, revolving corridor was studded with a swirling vortex of lights which served as a hypnotic beacon for the crew of the Lewis & Clark. Biddle even bolted the camera to the floor to create a sense of vertigo as the set swiveled upside-down around the actors. Biddle recalls, "We shot several sequences that involved the tunnel. That set was one piece, and the whole thing revolved 360 degrees, so it was a big challenge to light. There was no way to place individual lights inside the set, so we had a big rig all the way around it with lights on it that shined through the holes in the rotating walls. We had about 80 large 10Ks all along the outside pouring light in."

The First Containment, however, is merely the entrance way "to the room of evil," as Anderson dubs the Second Containment. The director explains, "It's a large circular room with huge spikes coming out of its walls. But because it was a different shape than traditional sets, with curved rather than flat walls, we didn't actually leave ourselves a huge amount of room to work in. The Second Containment was partially flooded as well, so if we weren't trying to stand on a curved wall, we were up to our ankles in water or we were standing in front of the rotating Third Containment in the center, which could knock you over."

To lend the Second Containment's circular chamber a threatening ambiance, Biddle once again opted to backlight through the walls' metallic grill work. "I couldn't really create claustrophobia in this huge set, which was like a big fishbowl, so I had to unnerve people with lighting," the cinematographer admits. "All of the characters ended up inside that particular set at one point or another. When they first come in, it's very dark, and when the power comes back up on the ship, the lighting changes. We used lasers, and did some practical pyro work in there as well. We had some lights coming from behind the walls and from the top as well. My gaffer, Kevin Day, who's worked with me on most of my pictures, put all of that in — not just small units, but major-kilowatt units. We'd go right up to 20K or so in the set. Every lamp we had on the whole movie was on a dimmer or had some sort of gel on it, so they all had to go back to a computer board, and Kevin did all of that. He's my right-hand man."

Biddle and his crew were constantly fighting the clock in the Containment sets, which had to be struck by a certain date. Despite the time crunch, Biddle did achieve some spectacular camera moves within the Second Containment's 360-degree "fishbowl" setup, with several rigs built either into or outside of the set. "We did some great shots in there," the cameraman enthuses. "Every shot in this movie was moving, except maybe a couple of effects shots. We dollied around the base of the sphere, and since the set didn't have a ceiling, we also reached down with a crane mounted outside the set and did boom moves up and down."

Anderson elaborates, "We did some very fluid, sweeping, lovely camera moves in this oddly-shaped set. Those moves, combined with the revolving gyroscope, created a great sense of movement. We also built a pivot point at the top of the set, right above the center of this huge room, so the camera could peer straight down at the Third Containment, and rotate as well."

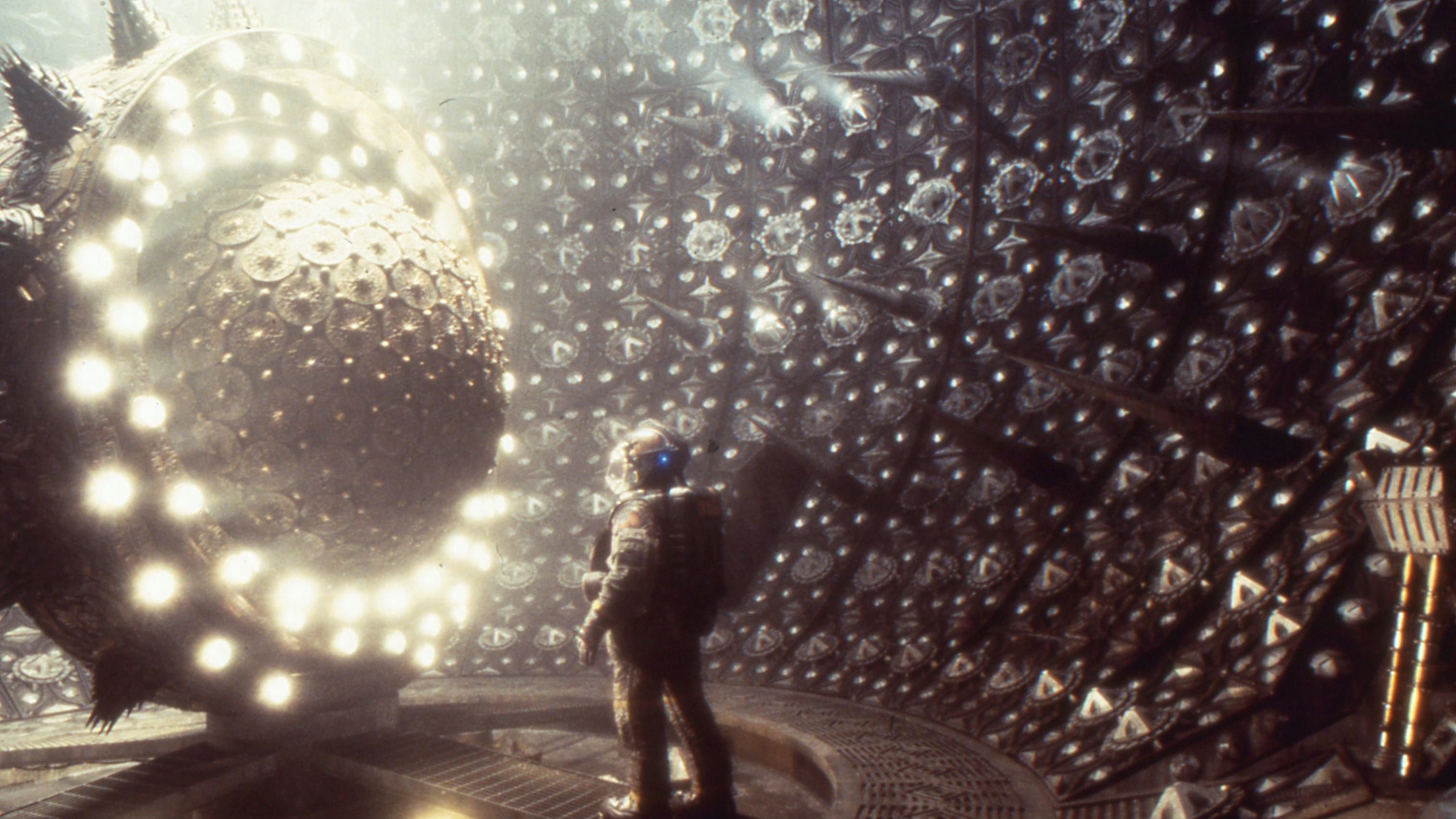

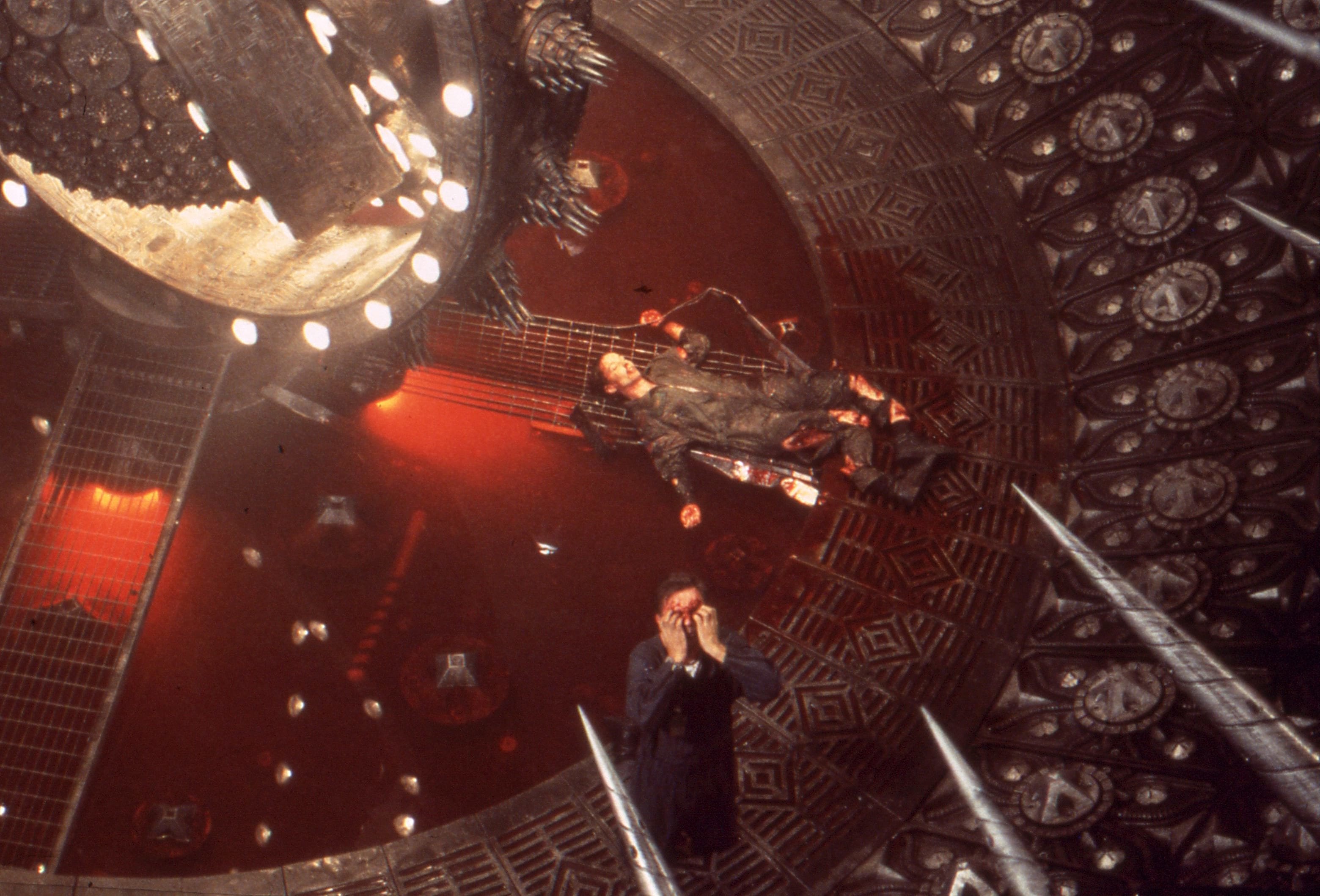

The Third Containment consists of a large, spinning gyroscope — layered with lethal spikes — that encloses the black hole powering the Event Horizon. "It's the evil heart of the ship," Anderson explains. "We wanted it to look so mean that you wouldn't want to be in the same room with it. I also wanted it moving all the time to give it an intelligence, and so that it would feel like a pulsating brain."

“The lights covering the sphere revolved like a huge ‘executive toy.’ It’s almost like an atom or a model of the universe; all of those things were involved in the design.”

visions of his

ex-wife, Weir

(Sam Neill)

clutches his

empty, bloodied

eye sockets

near the corpse

of Peters.

To create this effect, Biddle and Day put lights on tracks covering the sphere's surface, then set them in motion for each take. "We covered the Third Containment with 500-watt bulbs on strip rigs," Biddle explains. "The lights covering the sphere revolved like a huge 'executive toy.' It's almost like an atom or a model of the universe; all of those things were involved in the design. There were an awful lot of lights revolving on tracks around this sphere."

The Third Containment was also one of many set-pieces Biddle shot with actors against blue- and greenscreen. In one such sequence, the engineer of the Lewis & Clark is dragged into the sphere after touching it. "We shot a lot of that against bluescreen inside the set, and we took the sphere out and set it up against blue," Biddle says. "I worked very closely with [visual effects supervisor] Richard Yuricich on that. If ever I had a question, he helped me out."

Given Biddle's resume, he's become something of an specialist shooting scenes involving special effects. It's an expertise which the cameraman says arose "probably more by accident. If you're going to do a movie on stage, effects are usually part of it. You have to keep an eye on that aspect when working on those movies, but a lot of it is up to the effects unit. I don't think there's anything too difficult about working with effects, because in the end, you don't want an effect to look like an effect. I think the way to approach it is as if it's not an effects shoot. Although the elements you film may be complicated, in the end, they're only going to go into a shot that is meant to look natural."

Biddle maintains that digital technology actually freed up his cinematography on the effects-driven Event Horizon, "especially with shots involving blue and greenscreen, which we did quite often. We had a lot of wire-work whenever we had characters who went out into the zero-gravity of space, so I was happy about the prospect of digital wire removal. We shot both blue- and greenscreen depending on what the predominant color of the light was. If it was green, we used bluescreen, and vice-versa."

One of the film's more complex wire gags occurs when the Event Horizon's designer, Dr. William Weir (Sam Neill), tries to shoot Captain Miller (Laurence Fishburne) and misses, instead blowing a hole in a cathedral-shaped window. "Everything gets sucked out, including Sam Neill," Biddle laughs. "We did the shot inside the ship with a lot of wirework and practical explosions. It took forever to set up, and a couple of days to shoot. The area beyond the window was supposed to be outer space, but there was just black. Any shots of Sam Neill in space were done with bluescreen."

endures a

hellish ordeal in

the Second

Containment.

In the macabre world within the Event Horizon, evil manifests itself via visions of the most traumatic events in each character's past. Rather than using a stylized or surreal photographic treatment for these encounters with personal demons, Biddle deliberately chose a very matter-of-fact approach: "I treated them as if they were really there. It's up to the viewer to decide if the visions are reality or if they're just in the characters' minds."

Toying with the audience's idea of reality was exactly what the film's director was after. Since the Event Horizon's environment was already so extreme, Anderson feared that glowing visions would do little more than lend an artificial layer to something that was already unreal. "We wanted you to feel that the horror was right there in your face," he says. "There's no thin veil of dry ice between you and the nightmare."

This tactic is certainly effective in the soon-to-be-infamous scene in which Weir, driven mad by visions of his dead wife, rips out his own eyeballs. Notes Anderson, "He's standing in a brightly-lit medical bay; he isn't lurking in the shadows, he's right there in your face. I wanted show as much of it as was humanly possible without getting an NC-17 rating."

Man (Noah

Huntley)

appears in the

Main Access

Corridor. Biddle

lit the 140'-long

tunnel by

placing fixtures

along the

outside of its

frame.

There are other, powerful glimpses of what will happen to the crew if they make their way through the black hole's gateway and into a literal perdition. Perhaps the most disturbing vision of all is the appearance of "the Burning Man," a spectral representation of an individual Captain Miller was unable to rescue on a past mission. Instead of conceiving this grisly vision with an actor in a fire suit, Yuricich and Biddle combined several different elements. "We did several passes on the same set," Biddle says. "Sometimes we used motion control. I shot some of that, but we also had a bit of a second unit. The Burning Man involved a lot of different effects elements. To get the proper color saturation and not let it blow out, we shot the fire at f8 or f11. We had to lighten it up a bit, but it's a really amazing composite."

The fire almost got a bit out of hand, however. "Setting fire to things is tricky," Biddle says. "We nearly burned down the First Containment set! It didn't all burn down, but we had a bit of an insurance claim. We had to clear out of the Bond stage and move on to something else."

The cinematographer maintains that he is actually most content when shooting under less-than-hospitable conditions. While Event Horizon was one of his more challenging assignments, the cameraman says it was less complicated than the Neil Jordan film he shot on location in Ireland last summer. "Even though The Butcher Boy will look like it was an easier movie, it's set in 1962, and it had to be absolutely real. We did a lot of evening and day scenes in this little two-up and two-down house. The huge Event Horizon set on the Bond stage was great. It wasn't easy, because everything was so big, but it was actually easier working in that set than it was working in a really small house where a family is having an evening sing-song."

You'll find a story on the film’s visual effects work with visual effects supervisor Richard Yuricich, ASC here.