Few Against Many: 300

Director of photography Larry Fong revisits the Battle of Thermopylae for this action-packed comic book adaptation.

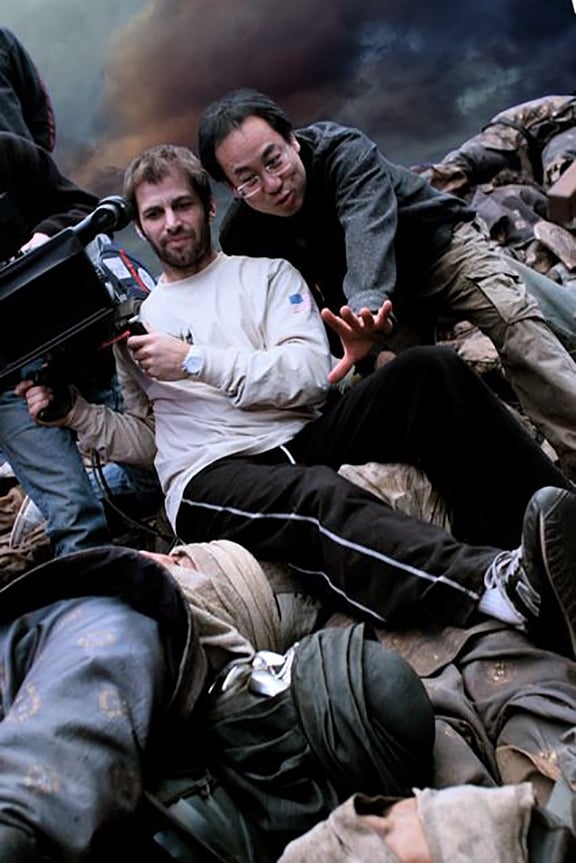

Unit photography by Takashi Seida

This article was originally published in AC April, 2007. Some images are additional or alternate.

The term “Spartan” has long been synonymous with “austere,” but the feature 300, replete with ferocious action, arresting imagery and a gripping story of self-sacrifice, could well change that association. Based on the graphic novel by author Frank Miller and artist Lynn Varley, the film, set in 480 B.C., depicts the heroics of Spartan king Leonidas (Gerard Butler), who battles a massive invading army of Persians with 300 of his loyal soldiers. Led by Xerxes (Rodrigo Santoro), the Persians number some 800,000 men, and if Leonidas’ men fail to stop them at the narrow coastal passage of Thermopylae, all of Greece could be lost. A classic study in asymmetrical warfare, the story was previously brought to the screen in the 1962 film The 300 Spartans, which was a primary inspiration for Miller.

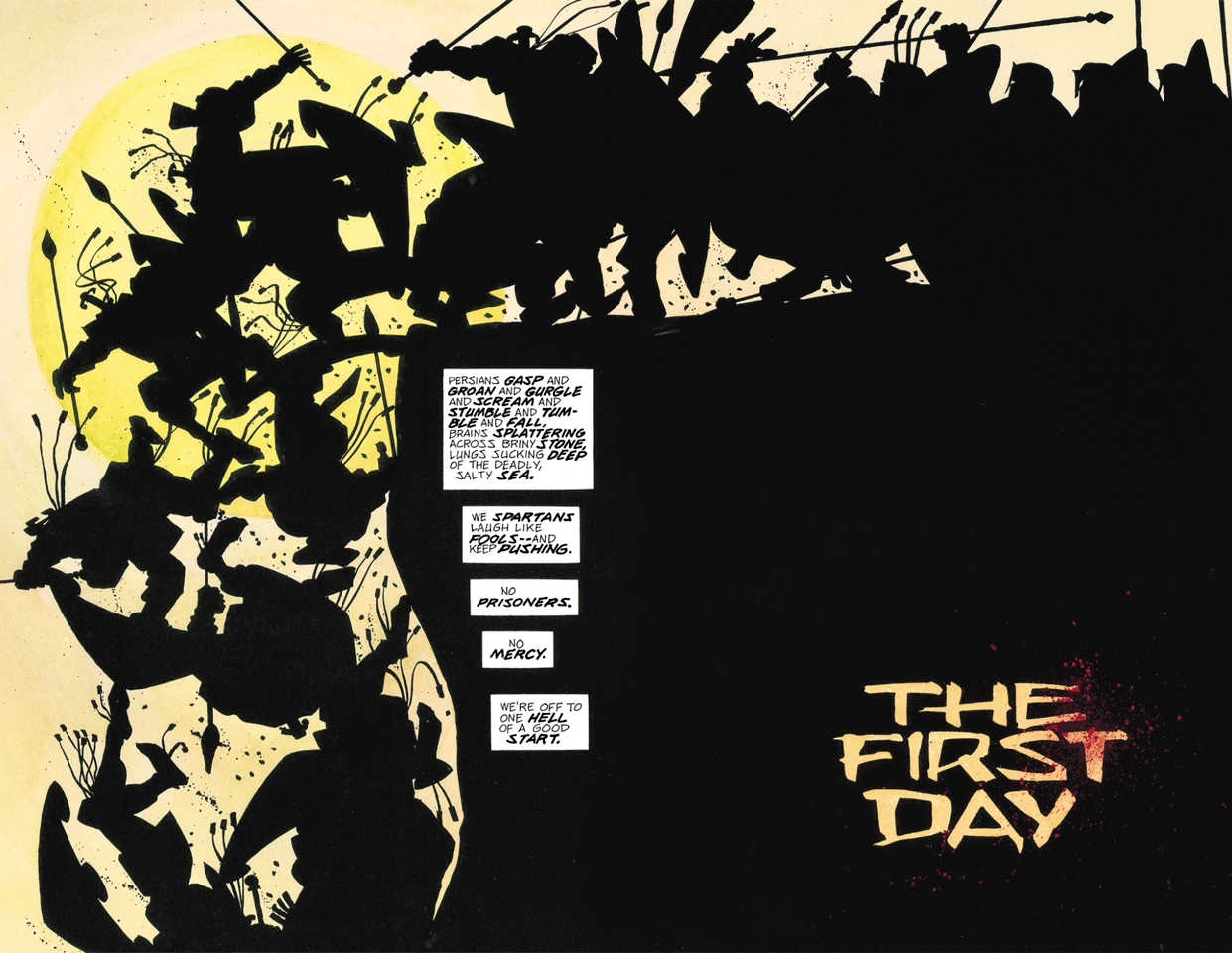

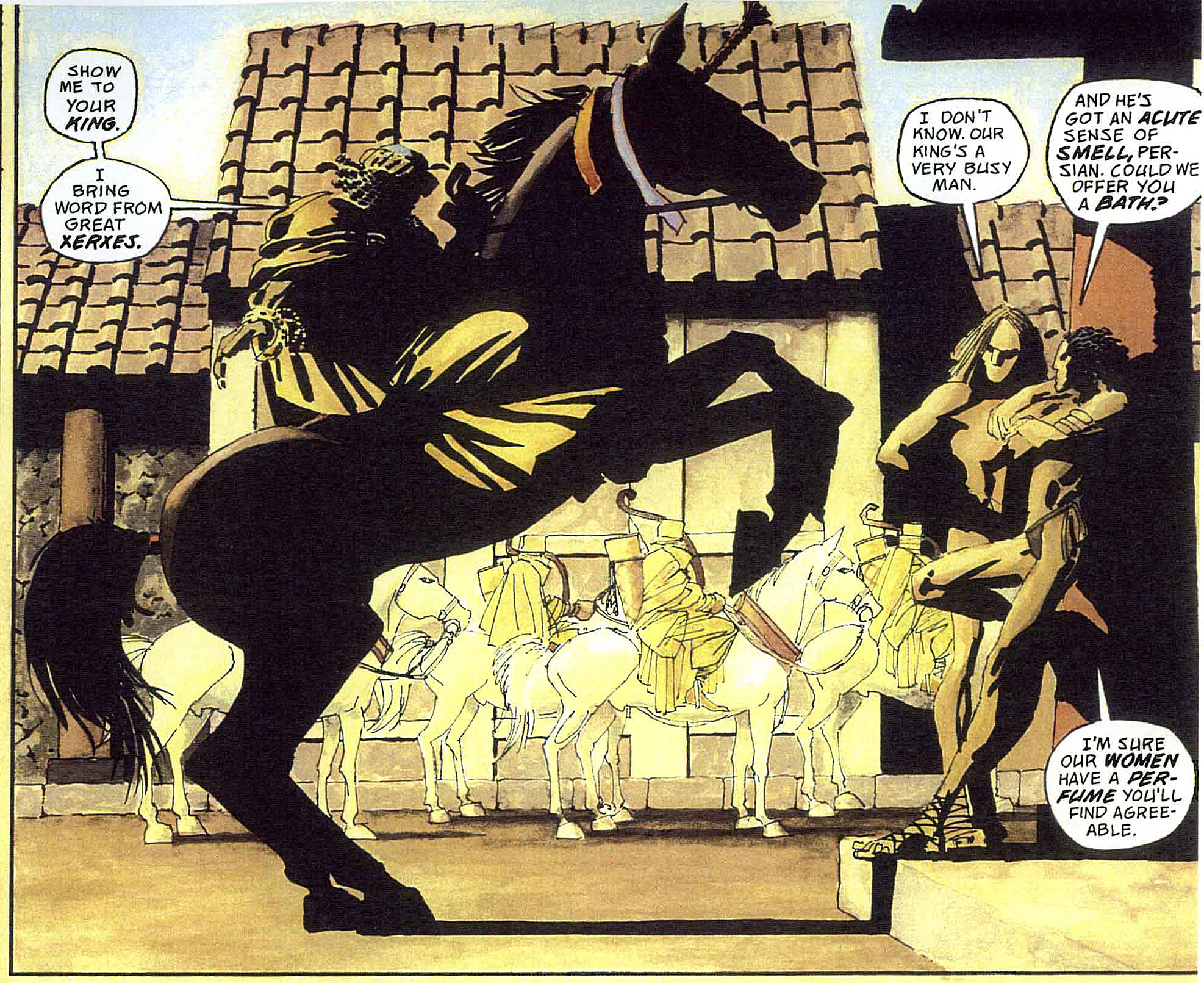

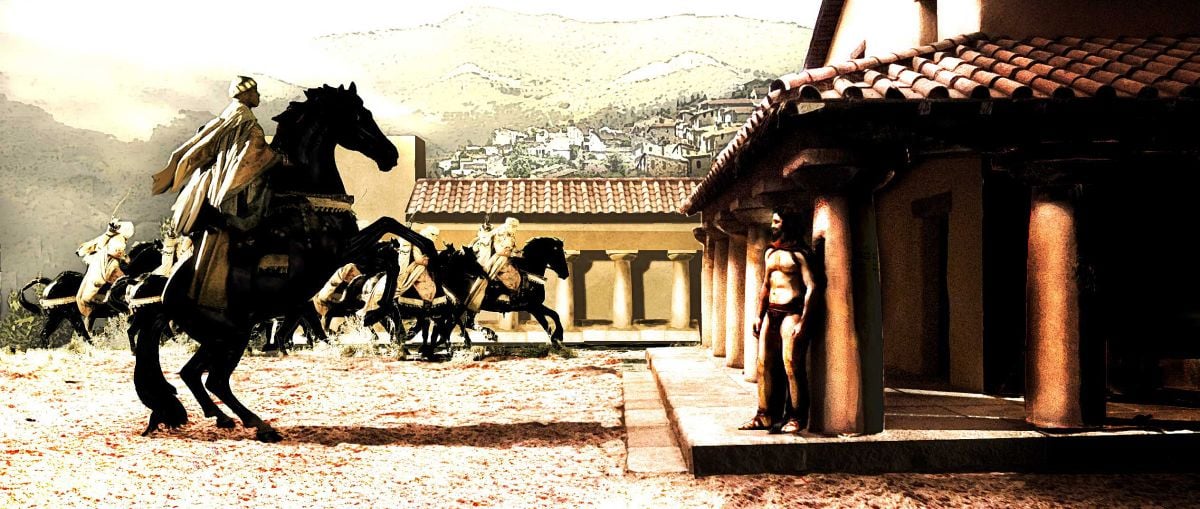

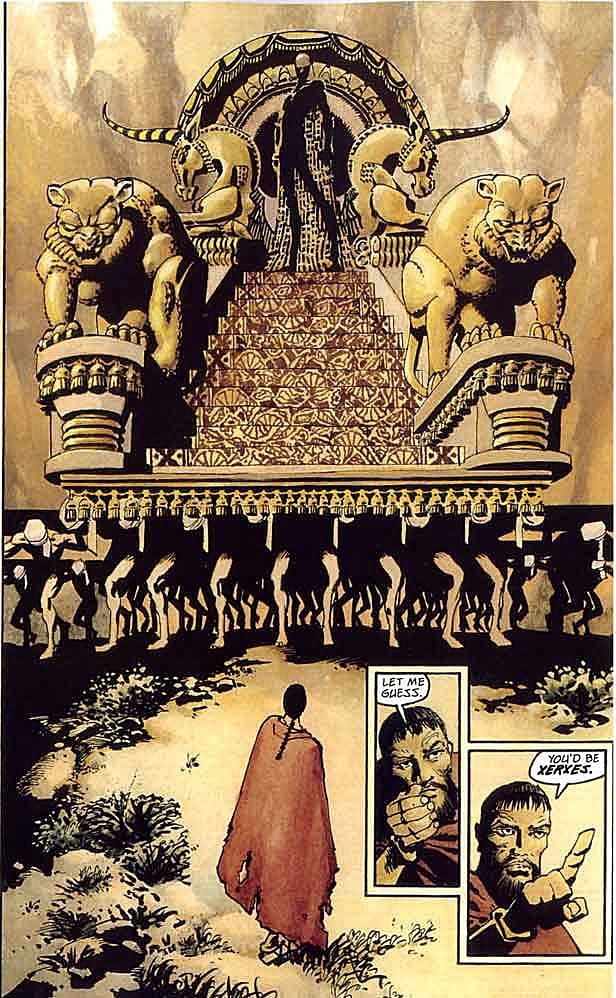

“Frank’s book was the blueprint for the look of our film,”says 300 director of photography Larry Fong. “We were not just making a film using his characters and story, we were specifically making a film out of his book, so its style and compositions were integral to everything we were doing. But we took license when necessary and also took advantage of what we could do on the big screen.” Miller notes, “Movies are an extension of illustration that adds the dimensions of time, space and movement to color and composition, so there are major differences in what you can do visually, but the story and characters are what it’s really about. I’m just happy 300 has been made by people who are as excited about those things as I am, and that they embraced all the storytelling tools of filmmaking.”

“That’s something I love about Zack: if he’s going to do something, he’s going to go all the way.”

— Larry Fong

Miller, whose graphic novel Sin City was brought to the screen by director Robert Rodriguez in 2005, joined the 300 production as a consultant. Although both Sin City and 300 made elaborate use of digitally treated images and computer-generated (CG) backgrounds, Miller notes that the pictures “are very different stylistically. Sin City is largely black-and-white with some use of specific color, whereas 300 has a limited palette but is full color, and has a much richer, more detailed look all around. I co-directed Sin City [with Rodriguez], but was very happy to stay on the sidelines with 300 and learn from what they were doing.”

Fong was unfamiliar with the events depicted in 300 before he came aboard to shoot the picture, but his long friendship and previous collaborations with director Zack Snyder gave him a smooth entry into the project’s complex digital production path, which included roughly 1,300 visual-effects shots. “I’ve known Zack since we both went to film school at the Art Center College of Design in Pasadena in the late 1980s,”says Fong. “We did a lot of projects together there, mostly Super 8 movies, and Zack was always very ambitious. For a World War I movie we did, he got permission from a neighbor to use his backyard as a location and immediately got a Bobcat out there and started digging trenches. It was like he was making Paths of Glory! That’s something I love about Zack: if he’s going to do something, he’s going to go all the way.”

After leaving Art Center, Fong and Snyder began working on music videos and commercials, often together. In 2004, both of them had breakthroughs, Fong with the hit series Lost (see AC Feb. ‘05) and Snyder with the horror remake Dawn of the Dead. “300 became our opportunity to work on a feature together, and I was very excited by that prospect,” says Fong, who earned an ASC Award nomination for his work on the Lost pilot.

“Zack started flagging certain pages as ‘Frank frames,’ meaning they had to be in the movie. The surrounding shots might not exactly match up, but those hero images were absolutely necessary.”

“One of the first steps was to break down Miller’s book and determine what illustrations would be matched exactly in the film in terms of lighting and composition. Fong explains, “Zack started flagging certain pages as ‘Frank frames,’ meaning they had to be in the movie. The surrounding shots might not exactly match up, but those hero images were absolutely necessary. Also, Frank used a lot of silhouette imagery in the book, so we had to decide whether we were going to commit to that exactly. Often, Zack and [visual-effects supervisor] Chris Watts would look at [ a silhouette shot] on the set and either approve it or say, ‘Maybe we should have a little fill light in there so we can decide later.’ As it turned out, I had to devise a lighting plan that would allow us to often go in several different directions within each setup, in part because the final look of the film and how we would achieve it in post weren’t nailed down until later in production. The look evolved during tests, and, thank God, we’d built in enough leeway to give us some flexibility [in post].

“I should note, too, that although people will see the film and say it looks exactly like the comic book, those illustrations were done in watercolor — they’re very graphic and stark. They don’t have the realistic look of, say, Frank Frazetta oil paintings. But they did absolutely drive the look of the film in terms of compositions; that allowed [production designer] Jim Bissell, [costume designer] Michael Wilkinson, and me to concentrate on lighting, colors and textures. The film is a close interpretation, especially in spirit.”

It was a given that 300 would employ extensive virtual landscapes and set extensions, requiring Fong to make great use of bluescreen. “Even if we’d had all the money in the world, we couldn’t have built the things in Frank’s book,” he says. “And even if we’d shot on real locations, we would have had to do a lot of digital work to re-create Frank’s world. The skies, for example, needed that painterly, surreal look that we could never have found in real life. So we embraced our CG world and never worried about trying to fool the audience into thinking it was real.” Fong chuckles at the memory of Snyder’s enthusiasm for this approach: “Throughout prep, Zack kept joking that we all had to ‘drink the Kool-Aid’ and sign onto this vision of his. He really seduced everyone with it, and he had to, because at first it was so different many people didn’t understand it, including me.”

Though Fong and Snyder were impressed by Sin City, which was shot on high-definition (HD) video, “we both knew HD wasn’t going to work for 300,” says Fong. “The primary problem was the amount of slow motion we wanted to use throughout our film. We looked at some digital systems that can be used for high-speed work, but they didn’t offer exactly what we wanted. Also, Zack and I really wanted to work on film. Even though 300 is full of CGI, it’s also a period piece, and we like the texture film brings to the image. The studio had some concerns — the expense of film stock, processing and scanning — but they supported the decision.”

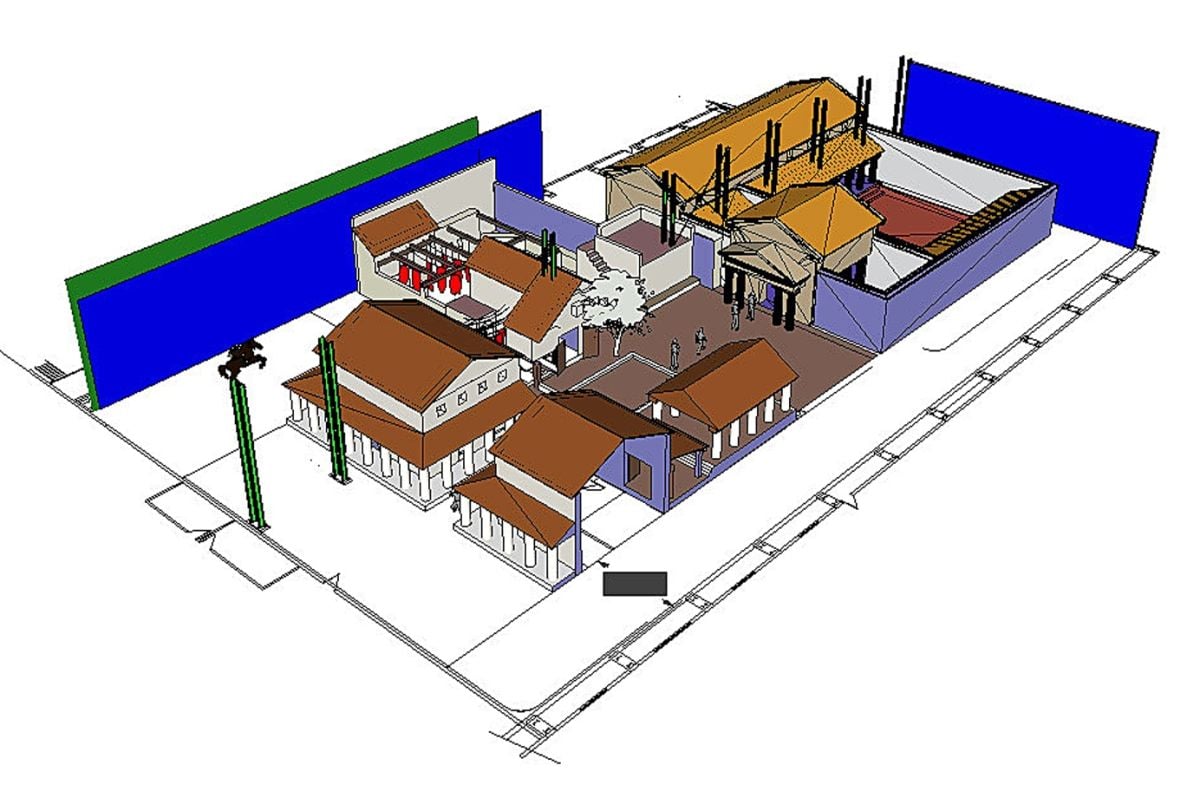

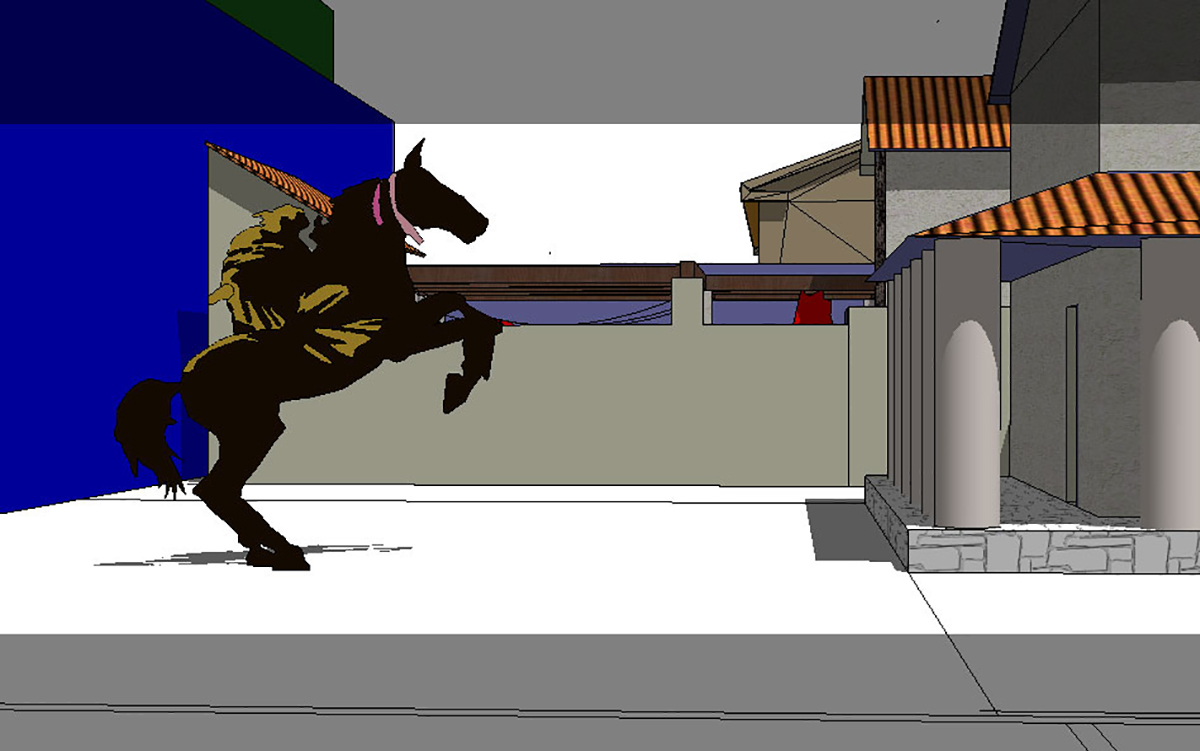

As for deciding how “virtual” they would go, Fong explains, “Zack’s mantra was, ‘If it’s close enough to touch, it has to be real.’ That meant Jim Bissell and his crew had to build extensive sets, and often only the deep backgrounds and skies would be CGI. With the exception of our battle sequences, which were largely shot against bluescreen, we always had sets to keep our orientation and help the actors. I don’t think our actors ever had to perform opposite tennis balls on sticks within a 360-degree bluescreen stage.”

Seeking an affordable space that would suit their needs, the filmmakers traveled to Montreal in July 2005 to inspect Ice Storm Studios. After this was secured as the production’s primary workspace, Fong arrived to find that large, custom, overhead lighting rigs that had been constructed for a previous project, The Day After Tomorrow, were still available for use. From the beginning, he knew he wanted to photograph 300 using an overall toplight approach: “It’s a look Zack and I both like, and it can really speed up production and look great if used properly. It thrilled me that we could recycle some of the lighting from Day After Tomorrow, because we didn’t have the money to build anything like that from scratch ourselves. Also, I was very lucky to get Jean Courteau as my gaffer — he had worked on Day After Tomorrow, so he knew the setup very well.” He adds that his Montreal crew members, including operator Daniel Suave, 1st AC Christian Lemay and key grip Alain Masse, were “extremely professional and prepared.”

The lighting bays were also completely dimmer-controlled, allowing Fong the flexibility to sculpt light throughout sets and easily increase illumination for high-speed work. “We were constantly fluctuating between 24 to 100 fps, which essentially quadruples the lighting budget,” he notes. “Finding those overhead rigs and using them as the basis for our system was a huge head start.”

He adds that the toplight approach was mandated by “the size of the stages, the size of our sets, and our need to run bluescreen around everything. Our sets were often built within 10 feet of the studio walls, and we also had to have space on the stage floor for all the Kino Flos uplighting our bluescreens. There wasn’t a lot of room to work with; in fact, that affected a few shots where we were trying to create a daylight look but couldn’t get our fixtures back far enough to create the right shadows. We were fortunate for the most part, but there were some compromises as well.” All the sets were built on risers, allowing the bluescreen to hang beyond the edge of the stage and conceal its lighting.

Though Fong had to create day and night looks for almost every set, “we only had these few stages fitted with our overhead bays, and budgetary restrictions prevented us from stopping to change out or gel all the lights inside them for a moonlit look and then change back again for warm daylight. The solution was to put up huge ½ CTB silks, so everything was slightly blue from the beginning, putting us right in the middle of the color-temperature zone. For a daylight look, we’d just go warmer in the timing, and for night we’d go cooler. Another thing differentiating the two looks was the color of our backlight and how it related to the overall illumination, which we could also adjust to create the feeling of dusk, overcast skies or full sun.

“For instance, in one sequence, Leonidas and his men march out of Sparta through a wheat field, and that’s played in full sun. We left the cool toplight and added a very strong backlight that was basically neutral, straight tungsten; the later tlming adjustment in overall warmth warmed up the backlight even more, creating a very golden, sunlit look in those highlights. This approach meant we had to change gels on just a few lamps rather than all of them, which saved a lot of time.”

With six weeks to prep for the 60-day shoot, Fong began camera tests in coordination with Bissell. “Thank God, Jim’s office was just down the hall from mine,” the cinematographer jokes. “We talked a lot about the concept art and the color scheme he’d come up with for Sparta. We couldn’t afford to shoot [ all tests] on film, so in some cases I took digital stills and then used Photoshop to approximate the movie’s final look, which we called ‘The Crush’ — clipped highlights and crushed shadows. I didn’t know exactly how our post process would work or how the movie would look, and that’s not a position any cinematographer wants to be in.” Throughout the shoot, Fong used Apple’s iPhoto to catalog and annotate his stills; this helped him communicate lighting and camera details to the second unit when necessary. He did “Crush” tests for almost every other department as well, including hair, makeup and props.

Shooting in Super 35 with Panavision and Arriflex cameras and Primo lenses, Fong tested Kodak and Fuji film stocks and found that Kodak Vision2 Expression 500T 5229 “worked best for underexposure. That was important, because I knew I was going to be in situations where I didn’t have enough light, specifically during high-speed work. We also liked the stock’s grain structure — we didn’t shy away from film grain at all. We ended up shooting the whole picture on 5229, processing it normally.

“We didn’t take all of our tests to the print stage, because there was so much work to be done on the image before that step that it would have been pointless,” he adds. The project’s digital intermediate (DI) was carried out at Company 3 with colorist Stefan Sonnenfeld. “Zack and I have worked with Stefan for many years, since he was a tape operator at The Post Group many years ago,” notes Fong.

One of the key elements to test was the fabric used for the Spartan warriors’ red robes. This material “slowly fades in intensity as the army is worn down in battle,” explains Fong. He tried to accompany each test shot with both a gray card and color chart. “It’s hard to get those in, even on a commercial,” he notes, “but we had a color chart on every roll of film we shot on 300. That was essential, given the work that was going to be done. We needed that reference to remain consistent.”

“We wanted to always present the men in an epic way.”

One concern during testing was how Fong’s toplight approach would work with the armor headgear worn by Leonidas and his men.” [Actor] Gerry Butler was very concerned about that, because his eyes were an important part of his performance,” says Fong. “Furthermore, the eye shadows were made more pronounced by the high-contrast ‘Crush’ look. So a lot of our tests had to do with eyelights; we often had a small Kino tube on a stand or held by someone, or a bounce fill created by a source going into a 4-by. Sometimes we’d just position several of those bounces around the set, with their positions corresponding to the eyelines. In the end we used a variety of methods, and it was difficult to keep the eyelight look consistent, especially in battle scenes, when a performer might be 20 feet away from [ the source]. We sometimes used a little rig that got dubbed the ‘Fong light’: a 2K bouncing into an attached 4-by-4 headboard on the same stand. We spent more time on eyelights on 300 than I have on any other project!”

Preproduction tests also revealed that bluescreen would work better than greenscreen. “The problem was the red in the Spartan capes,” explains Fong. “When the finished greenscreen test images were projected on the big screen, we noticed a weird color fringing, and we couldn’t quite figure out what the problem was. Bluescreen worked much better.”

The positioning of the Spartans in every composition was also a concern. “We wanted to always present the men in an epic way,” says Fong. “In a way it reminded us of the Pageant of the Masters at the Laguna Beach Festival of Arts.” In this annual event, costumed players are arranged behind a large picture frame to mimic famous works of art. “That became a kind of shorthand for Zack and me, an inside joke,” says Fong. “We’d look at a shot and say, ‘Yeah, that’s so Pageant of the Masters!”‘

As visual-effects art director Grant Freckelton continued to develop the final look of “The Crush” during production, “it became more contrasty, more monochromatic, somewhat desaturated,” recalls Fong. “It also became a very complicated process, using a lot of Photoshop steps that even I didn’t understand. So by the time we had to turn over the process to all the effects houses that were going to do the final work, Grant had to turn over our style guide, this Photoshop manifesto, so they could get the images just right.”

After Leonidas and his men take their defensive position at Thermopylae — a narrow chokepoint with a towering cliff on one side and the roiling Mediterranean Sea on the other — 300 vividly depicts their bloody clashes with wave after wave of Persian fighters. “For the battle scenes, we often had regular and high-speed units running simultaneously and then moved m for high-speed work on very specific action, like a guy flying through the air with a huge sword,” says Fong. “We used a lot of Arri 435ES and 235 bodies for [high-speed work], with Zack usually operating the 235. Some directors might have pushed [ that work] off to second unit, but Zack lived for it. He also likes weird frame rates, so instead of 48, 72 and 96 fps, we might run instead at 50, 75 and 100 fps. We used a PhotoSonics ER for really high-speed stuff, up to 360 fps.”

Early in the Spartans’ first battle, Leonidas charges ahead of his comrades, using a long spear and broadsword to slay a series of oncoming foes as the camera tracks along with him and records the action in extreme slow motion. At specific split-second points in this solo assault — Leonidas’ blade lopping off someone’s head, for example — the camera zooms in, captures the bloody moment, and zooms back out, the actor and the camera perfectly in sync. Fong smiles when asked how this was accomplished. “That’s one of the most complicated things we did photographically, but Zack had used a technique on an earlier project that actually made it pretty simple to execute.”

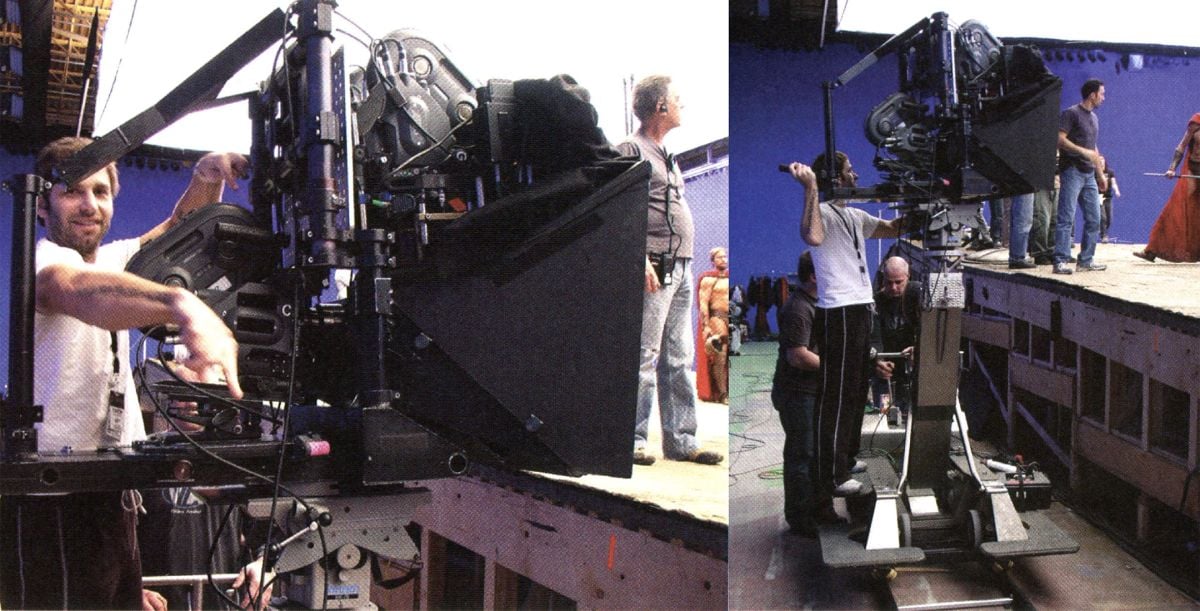

The telescoping effect was achieved with a multi-camera rig that simultaneously photographed the action with three different focal-length lenses; in post, the specific “zoom” points were chosen, and the filmmakers could digitally shift between the perspectives. “Three Arri 435ES cameras were mounted on the same head,” explains Fong. “Two were on top, shooting down into a beamsplitter, and one was positioned to shoot right through the beamsplitter. All three were in the same lens axis but using three different lenses — wide, medium and tight. In post, we could decide exactly when and where to rack in to a close-up on Leonidas. It’s basically a CG ‘morph’ zoom. Of course, people have created artificial zooms in post before, but they always pick up grain and other artifacts. With this system, you can find those precise moments in the action to highlight. The rig was very heavy and cumbersome, but the result was fantastic.”

The cinematographer notes that it would have been preferable to interlock the three cameras — creating frame-to-frame continuity between them — but it wasn’t necessary because the synthetic zoom concealed any perceptible jitter. “That footage was also a little underexposed, because not only were we shooting at 100 fps, but the beamsplitter took a lot of light out of it, at least half a stop. So the underexposure range of 5229 was really pushed, but because of our camera tests I was confident about what I would get.”

Aiding in the filming of kinetic battle sequences was a 30’ Technocrane. “We originally budgeted the Techno for a few days, but when it became clear how much time and energy we were saving, production quickly agreed to keep it on for a much longer time,” says Fong. “It became invaluable toward the end, in part because all the sets were elevated; laying track would have been difficult, so we saved a lot of time by just leaning in with the crane and using the extending arm to get shots that we would have otherwise done with a dolly. We also did a surprising number of close-ups with the Techno, which I was a little worried about at first. And, thanks to Chris Watts, we were able to use the Steadicam whenever we wanted.”

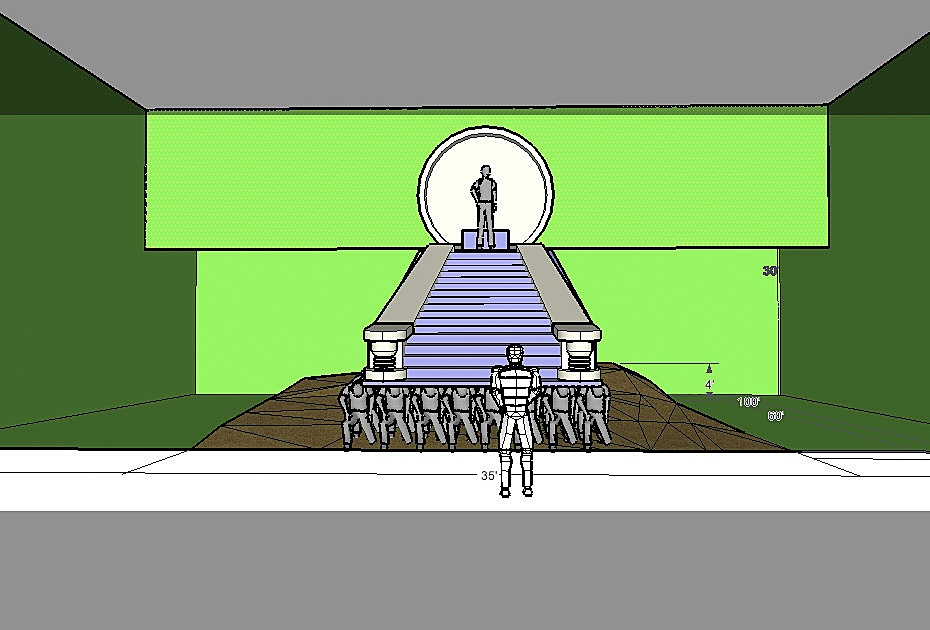

After the Spartans ruthlessly repel several waves of Persian attackers, Leonidas and Xerxes meet under a flag of truce to discuss their options. As in the comic, the ornately decorated Persian leader is depicted as a giant figure who looms over Leonidas. However, even at 6’2”, actor Rodrigo Santoro did not stand so tall over Gerard Butler. “Chris Watts figured out how much bigger Xerxes was supposed to be, and we created proper eyelines for Gerry and Rodrigo,” says Fong. “We then positioned them apart — but in the same frame — against bluescreen and they did the scene. Later, in post, they would be repositioned however was necessary, with Rodrigo scaled up, matching the eyelines.”

When feasible, Fong took full advantage of the fact that 300 would be heavily massaged in post. He saved time on set by planning to eliminate unwanted spill with a quick Power Windows fix, or digitally erase lamps left in shot. “If we could save 30 minutes of production time with a five-minute fix in post, we’d do it every time. It wasn’t about being lazy or sloppy, it was about using all the tools at hand to work smarter. For instance, we had some low-angle shots of Xerxes on a very ornate throne looking right over the edge of our wraparound bluescreen and up into our lighting bays. Instead of setting up a new bluescreen for the shot, we quickly attached sections of blue card to stands like flags, just to cover those edges. It was down and dirty, but it worked.”

Though the filmmakers employed every tool at their disposal for battle sequences, an intimate, pre-conflict romantic encounter between Leonidas and his queen, Gorgo (Lena Headey), made them get back to basics. “Lovemaking scenes are always interesting to shoot, because you have to be careful,” says Fong. “The actors are in a very vulnerable position, and you have to respect that. You also want them to look beautiful. So we lit the basics of the scene as we would any other — it was a night scene, so we had very soft, cool highlights — and Zack decided to go handheld once we got further into the scene. He likes to operate and often does on commercials. He wanted to be spontaneous, improvisational and just capture the energy of the scene. It was a closed set, so I was the only other person there, and I handheld a little Chimera softbox. We had set the backlight, a moonglow effect, so I was just adding a tiny bit of fill. I never even used my meter. In a way, it was like our early music-video days together!”

Fong smiles when asked to compare his experience on 300 to his assignment on Lost. “It was going from one extreme to the other. We were always at the mercy of the elements while filming Lost on location in Hawaii, but there’s a certain Zen mindset that takes over when there are things you can’t control. You adapt and find new ways of doing things. On 300, we had complete control despite some limitations, and that’s almost scarier.”

TECHNICAL SPECS

2.40:1

Super 35

Panaflex Platinum, Gold II;

Arri 435ES, 235; Photo-Sonics ER

Panavision Primo lenses

Kodak Vision2 Expression SOOT 5229

Digital Intermediate

Printed on Kodak Vision Premier 2393

Fong and Snyder would again collaborate in the features Watchmen, Sucker Punch and Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice. The cinematographer’s other credits include Super 8, Kong: Skull Island and The Predator. He was invited to join the ASC in 2011.

For access to 100 years of American Cinematographer reporting, subscribers can visit the AC Archive. Not a subscriber? Do it today.