Filming 2001: A Space Odyssey

This archival 1968 article recounts American Cinematographer’s brief encounter with Stanley Kubrick — republished on the 50th anniversary of this classic film’s release.

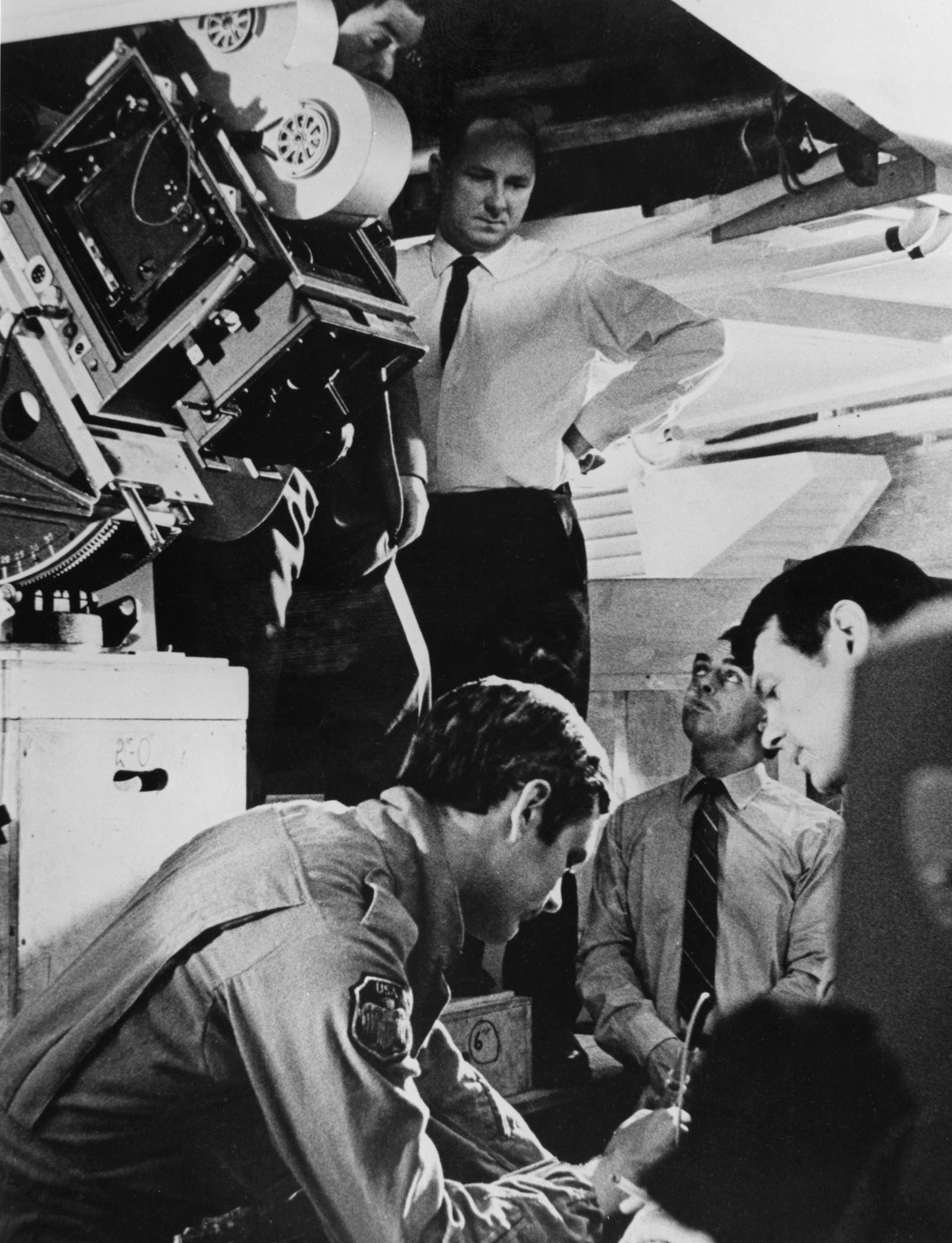

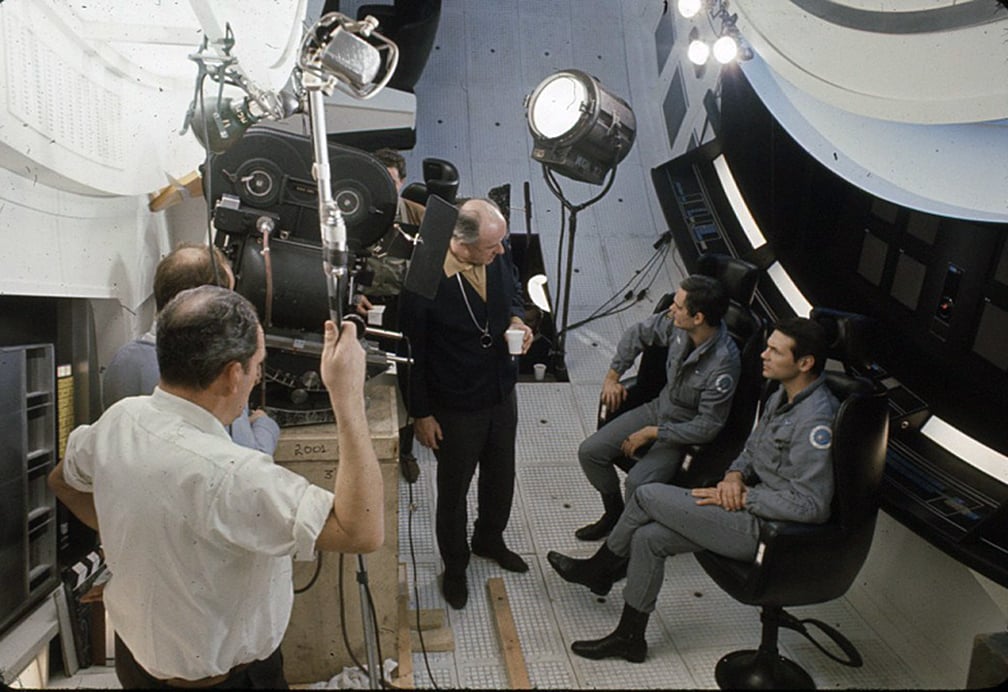

During my last trip to London a year and a half ago arrangements were made for me to meet with producer-director Stanley Kubrick who was at MGM’s Borehamwood studio working on his futuristic Super-Panavision spectacle 2001: A Space Odyssey. I was looking forward to talking with him and perhaps standing by during the filming of a scene or two of this production, which was being filmed in great secrecy but which had already become a kind of legend among those working on it.

On the morning of the day set for our get-together, I received a call from Kubrick's secretary. It seemed that he had encountered a crisis in the cutting room that would keep him tied up for the entire day. Would it be all right if we switched our appointment to the following day, she wanted to know. Unfortunately it wouldn't, because I was scheduled to leave England the next morning.

The upshot was that I didn’t get a chance to talk with him in depth about the production until after I had sat enthralled through a preview screening of the final cut. I was stunned by the scope and sheer visual beauty of this 70mm filmic excursion into the future, by the magnificent photography of Geoffrey Unsworth [BSC] and John Alcott [BSC], by the technical perfection of its multitude of enormously complex special effects — but most of all by the uncompromising dedication of the creative genius who had devoted four years of his life and unstinting effort to the realization of this dream on film. Listening to him tell about how it was made, I found myself caught up by his enthusiasm and tremendously impressed with the wealth of creative imagination which had been required to put it onto the screen.

2001 is no mere science-fiction movie. In truth, to be really accurate, it is more like “science-fact” simply extended a few decades into the future. In his quest for complete authenticity in terms of present and near-future technology, Kubrick consulted constantly with more than 30 technical experts and the results, with the possible exception of an “uptight” computer, are an accurate forecast of things to come.

A Story Far Out In Time and Technique

In order that the enormity of the challenge may be fully appreciated, it is necessary, briefly, to synopsize the story of the film.

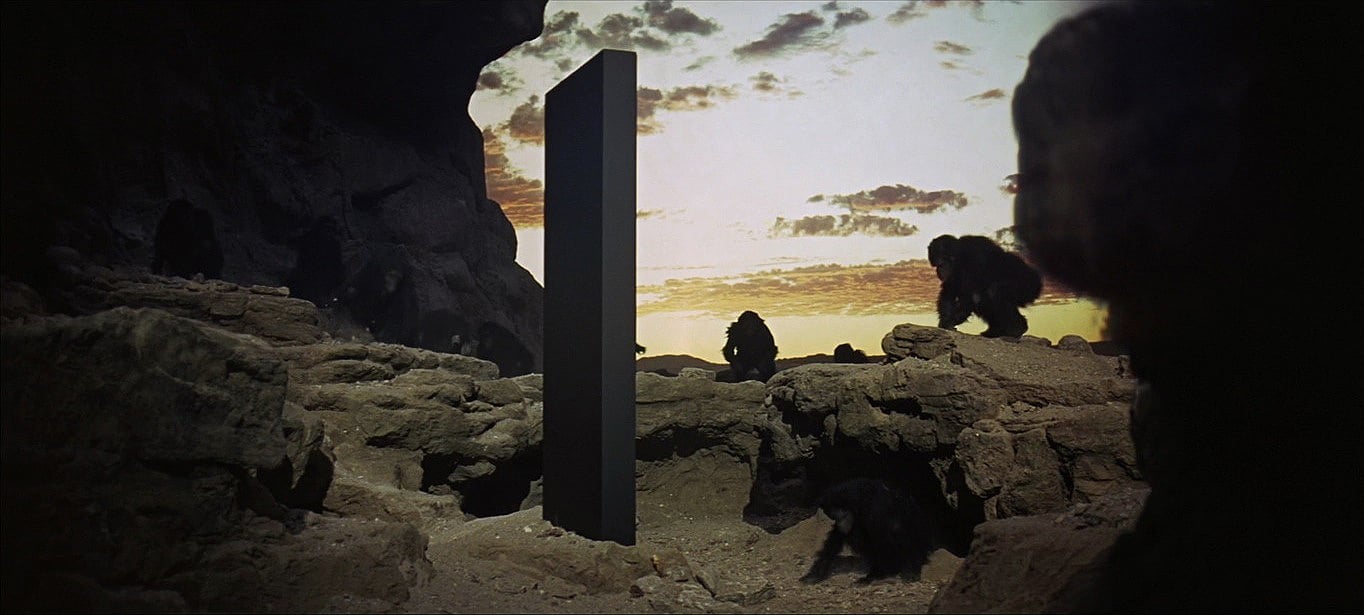

The picture opens with an awesome prologue entitled “The Dawn of Man,” in which apelike pre-humans are seen (during an era occurring 4,000,000 years ago) in action against spectacular natural backgrounds. Out of this rugged terrain there arises one morning a smooth, black, rectilinear monolith which first frightens the ape-men and then attracts them.

The time of the film then flashes forward to the year 2001, A.D.

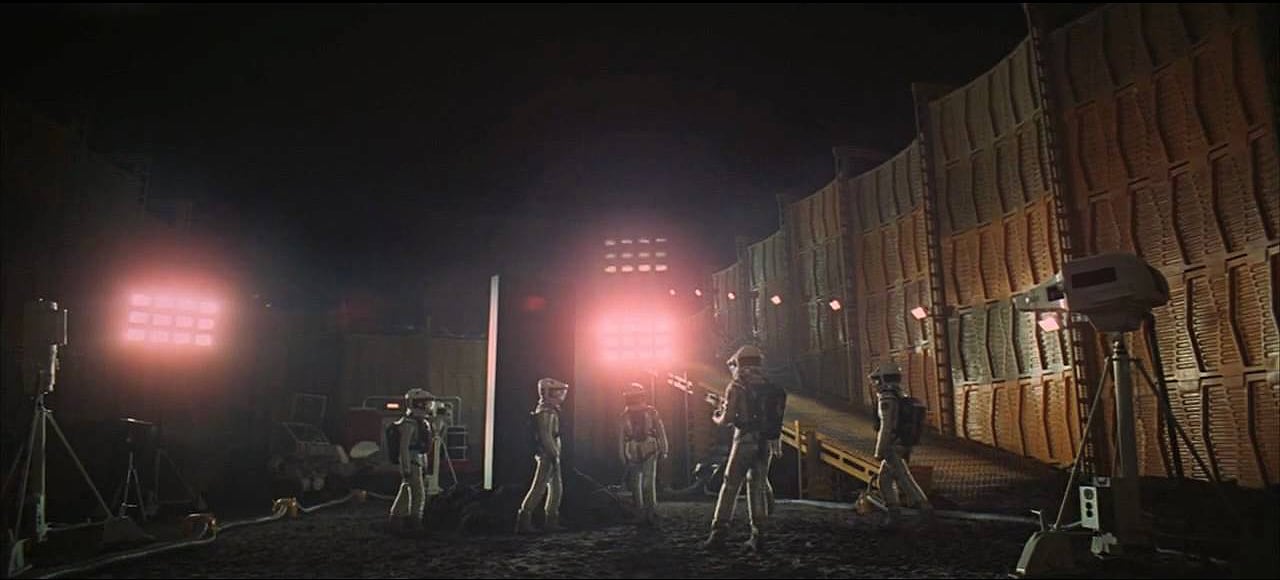

A United States envoy is sent on a secret mission to the moon to investigate a strange “made” object uncovered in an excavation of the crater Tycho. It turns out to be the same large monolith which we have seen in the previous sequence — except that now it is emitting a high-pitched signal apparently beamed at the planet Jupiter.

“It was a novel thing for me to have such a complicated information-handling operation going, but it was absolutely essential for keeping track of the thousands of technical details involved.”

— Stanley Kubrick

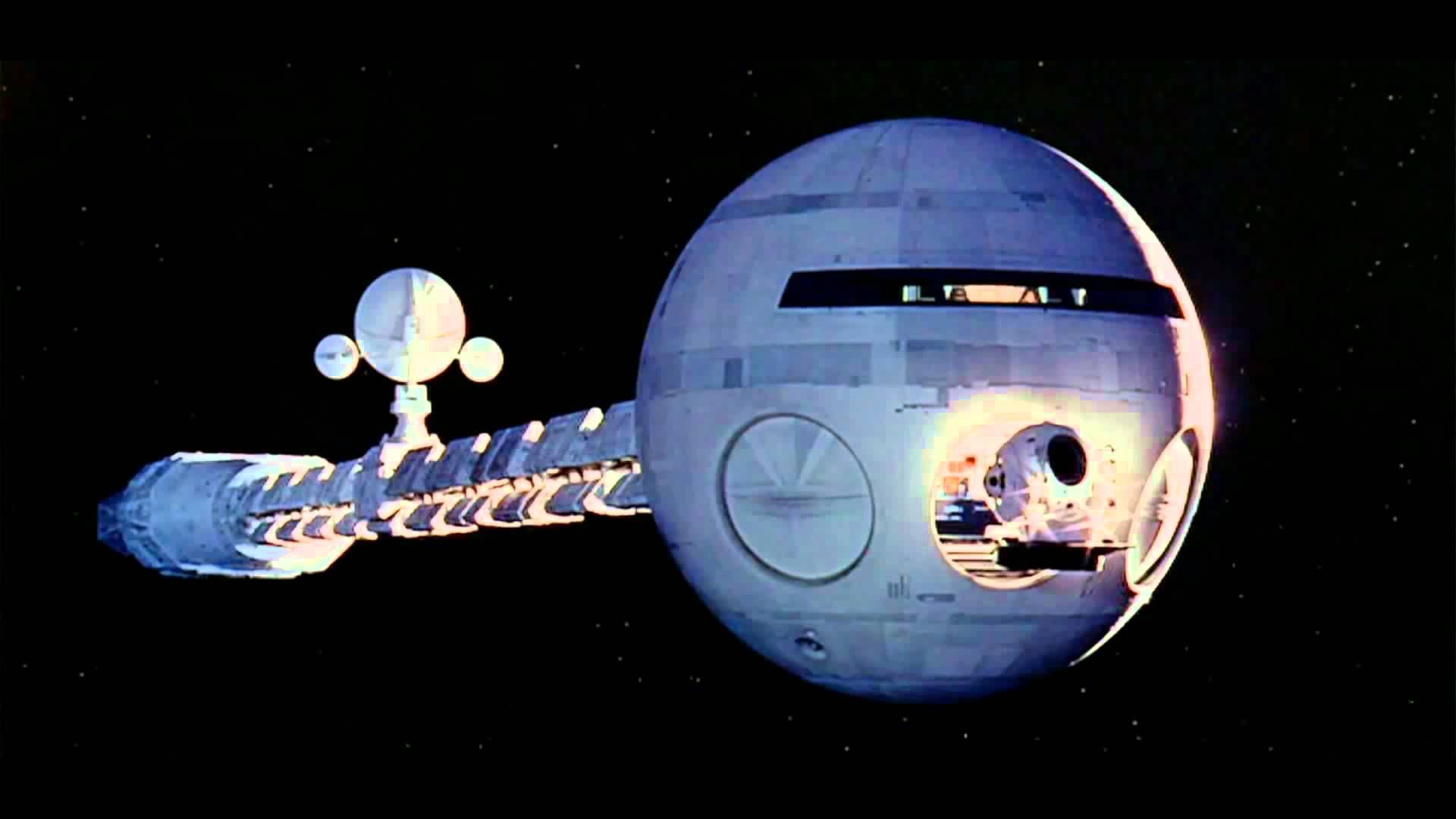

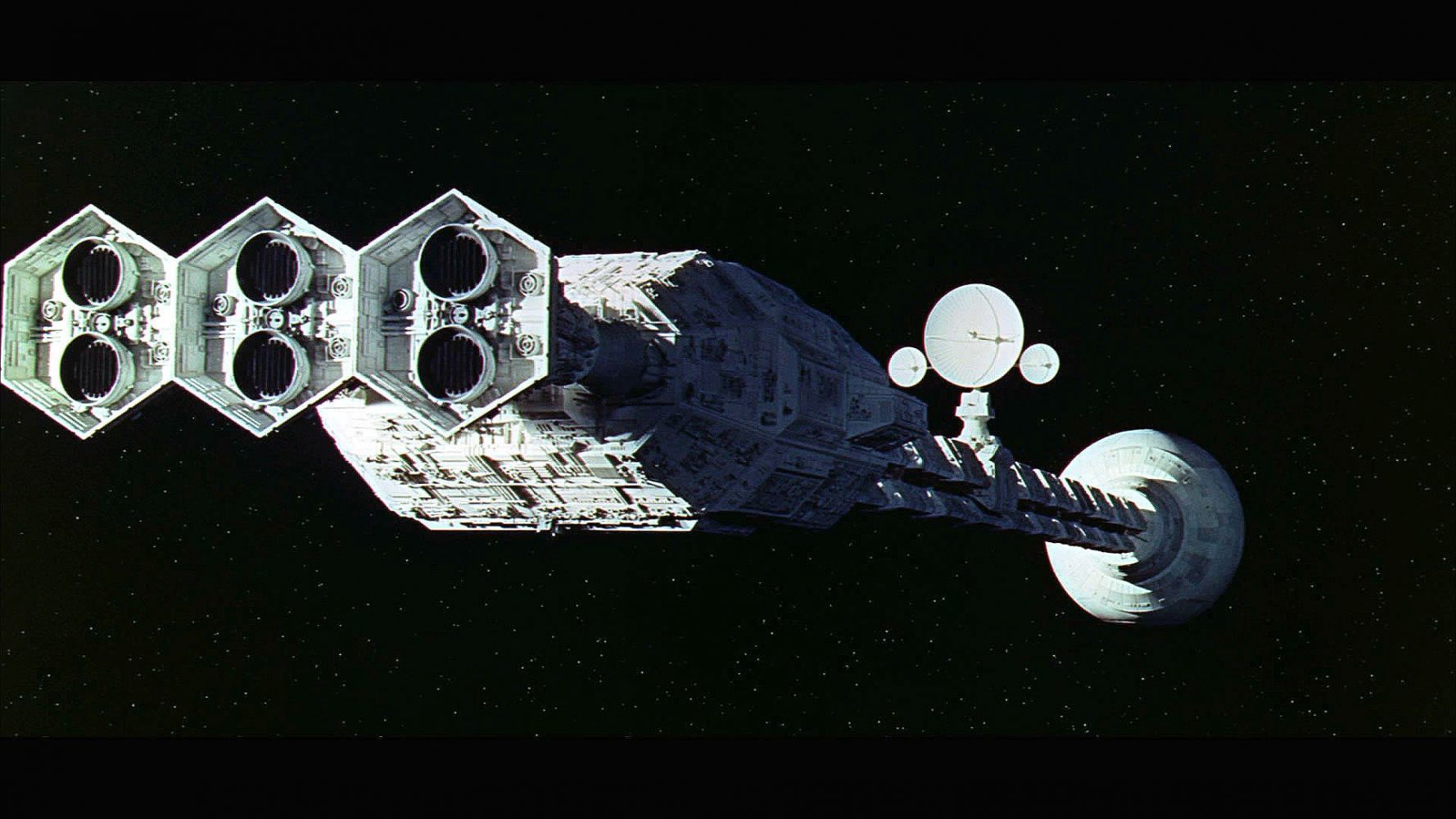

It’s decided to send an immense spacecraft, the Discovery, to Jupiter for purposes of investigation. The gigantic vehicle is manned by two superbly self-controlled young astronauts (played by Keir Dullea and Gary Lockwood), with a back-up crew of three others resting in a state of quick-frozen suspended animation within “hibernaculums” that resemble mummy cases. The sixth personality aboard the spacecraft is an almost-human computer named HAL that talks in a dreamy voice and ultimately goes off the neurotic deep end.

The main area of the Discovery is a huge centrifuge that rotates at the rate of three miles-per-hour to nullify the weightless effect by means of artificial gravity. Inside their space-age ferris wheel, the astronauts do their roadwork and casually walk upside down.

Also Read: Cinematographer Larry Smith and Stanley Kubrick Craft the Dreamlike World of Eyes Wide Shut

When HAL makes an error in mechanical judgment, the astronauts decide to disconnect all but his most basic functions. However, the computer discovers the plot and, in a fit of all-too-human self-preservative frenzy, kills one of the astronauts when he goes outside of the mother ship to make repairs, executes the deep-frozen trio in their sarcophagi by cutting off their life support, and attempts to prevent the remaining astronaut from re-entering the Discovery. This plot is foiled when the cool young man, caught outside without his helmet, blasts his way through the vacuum of space into an air-lock of the mother ship.

With almost surgical objectivity he then proceeds to lobotomize the rebellious (and now contrite) computer by pulling out its “brain cells” one-by-one. Left as the sole survivor, he steers his course toward Jupiter. Approaching the huge planet he is drawn into a vortex of “psychedelic” color, rushing geometric corridors of infinite length and a galaxy of magnificently hued starbursts. Finally, he steps from the one-man pod into a lavish living-bedroom suite that boasts a luminous floor and Louis XVI furniture. He sees himself aging progressively until, as a very ancient senior citizen he reaches out in supplication toward the by-now-familiar monolith which stands at the foot of his bed.

The last sequence in the film shows a “starchild” embryo with glowing eyes which seems to emerge from the fusion of planets to go soaring through space in cosmic concert with the monolith.

The Behind-the-Scenes of A Great Film Adventure

Knowing of the air-tight security which had attended filming of the special effects for this production, I was a bit apprehensive about asking Stanley Kubrick to discuss the intricate technology involved.

However, in my lengthy discussion with him (an occurrence which some journalists might aptly refer to as an “exclusive interview”), I found him to be completely co-operative. He answered my questions fully and often volunteered additional information, seeming actually eager to share his considerable know-how with the professional filmmakers who constitute the great majority of the American Cinematographer readership.

I had heard about the elaborate “command post” which had been set up at Borehamwood during the production of 2001. It was described to me as a huge, throbbing nerve center of a place with much the same frenetic atmosphere as a Cape Kennedy blockhouse during the final stages of countdown.

“It was a novel thing for me to have such a complicated information-handling operation going, but it was absolutely essential for keeping track of the thousands of technical details involved,” Kubrick explained. “We figured that there would be 205 effects scenes in the picture and that each of these would require an average of 10 major steps to complete. I define a ‘major step’ as one in which the scene is handled by another technician or department. We found that it was so complicated to keep track of all of these scenes and the separate steps involved in each that we wound up with a three-man sort of ‘operations room’ in which every wall was covered with swing-out charts including a shot history for each scene. Every separate element and step was recorded on this history-information as to shooting dates, exposure, mechanical processes, special requirements and the technicians and departments involved. Figuring 10 steps for 200 scenes equals 2,000 steps — but when you realize that most of these steps had to be done over eight or nine times to make sure they were perfect, the true total is more like 16,000 separate steps. It took an incredible number of diagrams, flow-charts and other data to keep everything organized and to be able to retrieve information that somebody might need about something someone else had done seven months earlier. We had to be able to tell which stage each scene was in at any given moment — and the system worked.”

“There were no color interpositives used for combining the shots, and I think this is principally responsible for the lack of grain and the high degree of photographic quality we were able to maintain.”

The Ideal Of The “Single-Generation Look”

A film technician watching 2001 cannot help but be impressed by the fact that the complex effects scenes have an unusually sharp, crisp and grain-free appearance — a clean “single-generation look,” to coin a phrase. This is especially remarkable when one stops to consider how many separate elements had to be involved in compositing some of the more intricate scenes.

This circumstance is not accidental, but rather the result of a deliberate effort on Kubrick's part to have each scene look as much like "original" footage as possible. In following this pursuit, he automatically ruled out process shots, ordinary traveling-matte shots, blue-backings and most of the more conventional methods of optical printing.

“We purposely did all of our duping with black-and-white, three-color separation masters,” he points out. “There were no color interpositives used for combining the shots, and I think this is principally responsible for the lack of grain and the high degree of photographic quality we were able to maintain. More than half of the shots in the picture are dupes, but I don’t think the average viewer would know it. Our separations were made, of course, from the original color negative and we then used a number of bi-pack camera-printers for combining the material. A piece of color negative ran through the gate while, contact-printed onto it, actually in the camera, were the color separations, each of which was run through in turn. The camera lens ‘saw’ a big white printing field used as the exposure source. It was literally just a method of contact printing. We used no conventional traveling mattes at all, because I feel that it is impossible to get original-looking quality with traveling mattes.”

Smooth Trips for Star-Voyagers

A recurring problem arose from the fact that most of the outer-space action had to take place against a starfield background. It is obvious that as space vehicles and tumbling astronauts moved in front of these stars they would have to “go out” and “come back on” at the right times — a simple matter if conventional traveling mattes were used. But how to do it a better way?

The better way involved shooting the foreground action and then making a 70mm print of it with a superimposed registration grid and an identifying frame number printed onto each frame. The grid used corresponded with an identical grid inscribed on animation-type platens.

Twenty enlargers operated by 20 girls were set up in a room and each was given a 5' or 6' segment of the scene. She would place one frame at a time in the enlarger, line up the grid on the frame with the grid on her platen and then trace an outline of the foreground subject onto an animation cel. In another department the area enclosed by the outline would be filled in with solid black paint.

The cels would then be photographed in order on the animation stand to produce an opaque matte of the foreground action. The moving star background would also be shot on the animation stand, after which both the stars and the matte would be delivered to Technicolor Ltd. for the optical printing of a matted master with star background. Very often there were several foreground elements, which meant that the matting process had to be repeated for each separate element.

The Mechanical Monster with the Delicate Touch

In creating many of the effects, especially those involving miniature models of the various spacecraft, it was usually necessary to make multiple repeat takes that were absolutely identical in terms of camera movement. For this purpose, a camera animating device was constructed with a heavy worm-gear 20' in length. The large size of this worm gear enabled the camera mount of the device to be moved with precise accuracy. A motorized head permitted tilting and panning in all directions. All of these functions were tied together with selsyn motors so that moves could be repeated as often as necessary in perfect registration.

For example, let us assume that a certain scene involved a fly-by of a spaceship with miniature projection of the interior action visible through the window. The required moves would be programmed out in advance for the camera animating device. A shot would then be made of the spaceship miniature with the exterior properly lighted, but with the window area blacked out. Then the film would be wound back in the camera to its sync frame and another identical pass would be made. This time, however, the exterior of the spacecraft would be covered with black velvet and a scene of the interior action would be front-projected onto a glossy white card exactly filling the window area. Because of the precision made possible by the large worm gear and the selsyn motors, this exact dual maneuver could be repeated as many times as necessary. The two elements of the scene would be exposed together in perfect registration onto the same original piece of negative with all of the moves duplicated and no camera jiggle.

Often, for a scene such as that previously described, several elements would be photographed onto held-takes photographed several months apart. Since light in space originates from a sharp single point source, it was necessary to take great pains to make sure that the light sources falling on the separate elements would match exactly for angle and intensity.

Also, since the elements were being photographed onto the same strip of original negative, it was essential that all exposures be matched precisely. If one of them was off, there would be no way to correct it without throwing the others off. In order to guard against this variation in exposure very precise wedge-testing was made of each element, and the wedges were very carefully selected for color and density. But even with all of these precautions there was a high failure rate and many of the scenes had to be redone.

“We shot most of these scenes using slow exposures of 4 seconds per frame, and if you were standing on the stage you would not see anything moving.”

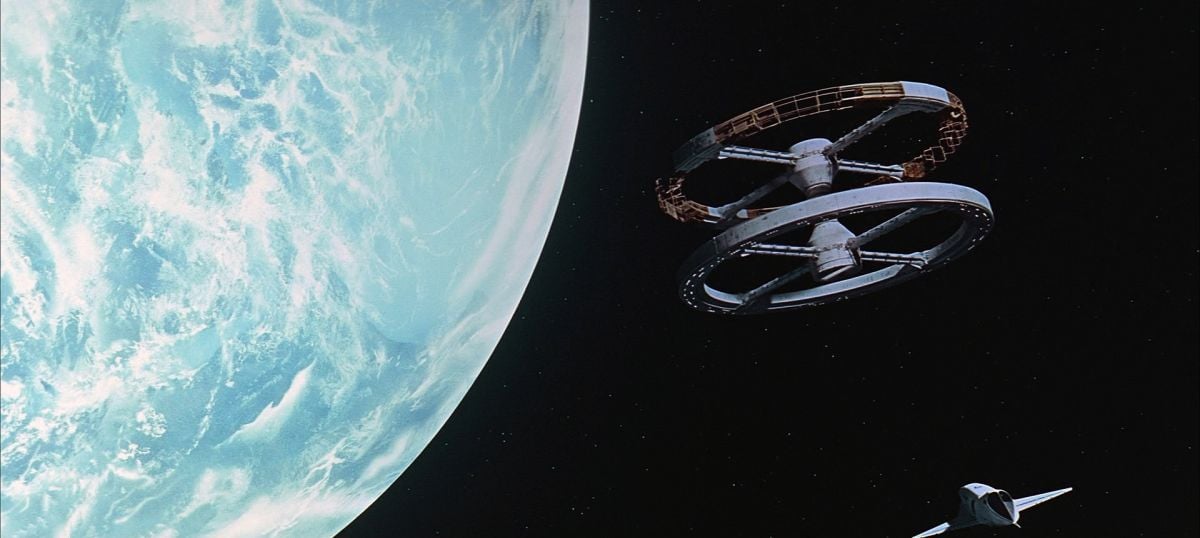

Filming the Ultimate in Slow Motion

In the filming of the spacecraft miniatures, two problems were encountered which necessitated the shooting of scenes at extremely slow frame rates. First, there was the matter of depth of field. In order to hold both the forward and rear extremities of the spacecraft models in sharp focus, so that they would look like full-sized vehicles and not miniatures, it was necessary to stop the aperture of the lens down to practically a pinhole. The obvious solution of using more light was not feasible because it was necessary to maintain the illusion of a single bright point light source. Secondly, in order to get doors, ports and other movable parts of the miniatures to operate smoothly and on a "large" scale, the motors driving these mechanisms were geared down so far that the actual motion, frame by frame, was imperceptible.

“It was like watching the hour hand of a clock," says Kubrick. “We shot most of these scenes using slow exposures of 4 seconds per frame, and if you were standing on the stage you would not see anything moving. Even the giant space station that rotated at a good rate on the screen seemed to be standing still during the actual photography of its scenes. For some shots, such as those in which doors opened and closed on the space ships, a door would move only about 4" during the course of the scene, but it would take five hours to shoot that movement. You could never see unsteady movement, if there was unsteadiness, until you saw the scene on the screen — and even then the engineers could never be sure exactly where the unsteadiness had occurred. They could only guess by looking at the scene. This type of thing involved endless trial and error, but the final results are a tribute to MGM’s great precision machine shop in England.”

It's All Done With Wires — But You Can't See Them

Scenes of the astronauts floating weightlessly in space outside the Discovery — and especially those showing Gary Lockwood tumbling off into infinity after he has been murdered by the vengeful computer — required some very tricky maneuvering.

For one thing, Kubrick was determined that none of the wires supporting the actors and stunt men would show. Accordingly, he had the ceiling of the entire stage draped with black velvet, mounted the camera vertically and photographed the astronauts from below so that their own bodies would hide the wires.

“We established different positions on their bodies for a hip harness, a high-back harness and a low-back harness,” he explains, “so that no matter how they were spinning or turning on this rig — whether feet-first, headfirst or profile — they would always cover their wires and not get fouled up in them. For the sequence in which the one-man pod picks Lockwood up in its arms and crushes him, we were shooting straight up from under him. He was suspended by wires from a track in the ceiling and the camera followed him, keeping him in the same position in the frame as it tracked him into the arms of the pod. The pod was suspended from the ceiling also, hanging on its side from a tubular frame. The effect on the screen is that the pod moves horizontally into the frame to attack him, whereas he was actually moving toward the pod.”

To shoot the scene in which the dead astronaut goes spinning off to become a pinpoint in space took a bit of doing. “If we had actually started in close to a 6' man and then pulled the camera back until he was a speck, we would have had to track back about 2,000' — obviously impractical,” Kubrick points out. “Instead, we photographed him on 65mm film simply tumbling about in full frame. Then we front-projected a 6" image of this scene onto a glossy white card suspended against black velvet and, using our worm-gear arrangement, tracked the camera away from the miniature screen until the astronaut became so small in the frame that he virtually disappeared. Since we were re-photographing an extremely small image there was no grain problem and he remained sharp and clear all the way to infinity.”

The same basic technique was used in the sequence during which the surviving astronaut, locked out of the mother ship by the computer, decides to pop the explosive bolts on his one-man pod and blast himself through the vacuum of space into the airlock. The airlock set, which appears to be horizontal on the screen, was actually built vertically so that the camera could shoot straight up through it and the astronaut would cover with his body the wires suspending him.

First a shot was made of the door alone, showing just the explosion. Then an over-cranked shot of the astronaut was made with him being lowered toward the camera at a frame rate which made him appear to come hurtling horizontally straight into the lens. The following shot was over-cranked as he recovered and appeared to float lazily in the airlock.

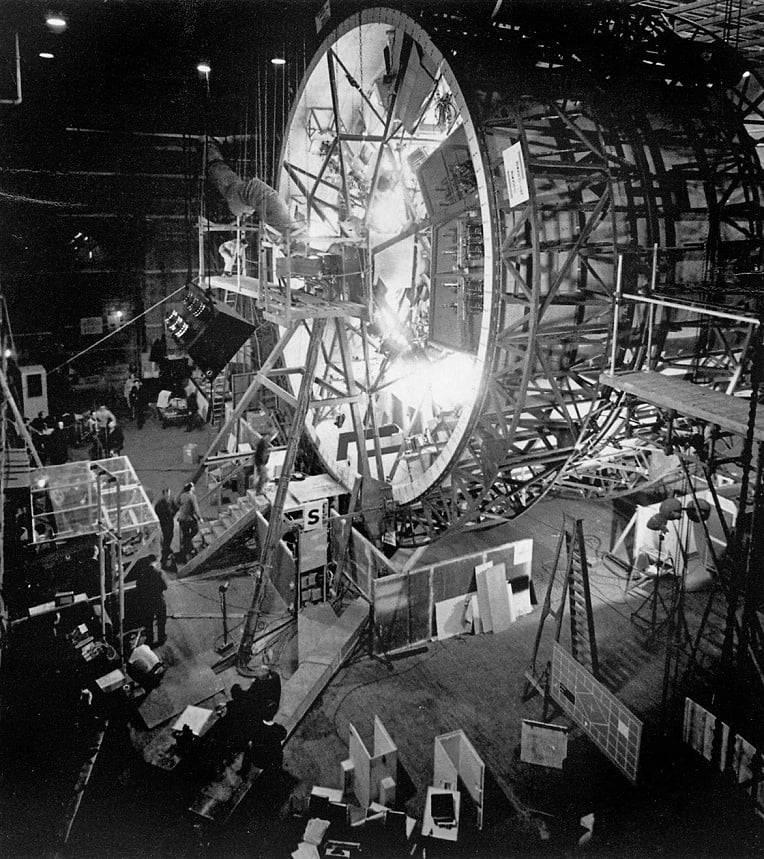

A Fascinating Ferris Wheel

2001: A Space Odyssey abounds in unusual settings, but perhaps the most exotic of them all is the giant centrifuge which serves as the main compartment of the Discovery spacecraft and is, we are told, an accurate representation of the type of device that will be used to create artificial gravity for overcoming weightlessness during future deep-space voyages.

Costing $750,000, the space-going “ferris wheel” was built by the Vickers-Armstrong Engineering Group. It was 38' in diameter and about 10' in width at its widest point. It rotated at a maximum speed of three miles per hour and had built into it desks, consoles, bunks for the astronauts and tomb-like containers for their hibernating companions.

“All of the lighting for the scenes inside the centrifuge came from strip lights along the walls. Some of the units were concealed in coves, but others could be seen when the camera angle was wide enough.”

All of the lighting units, as well as the rear-projectors used to flash readouts onto the console scopes, had to be firmly fixed to the centrifuge structure and be capable of functioning while moving in a 360-degree circle. The magazine mechanisms of the Super-Panavision cameras had to be specially modified by Panavision to operate efficiently even when the cameras were upside down.

“There were basically two types of camera set-ups used inside the centrifuge,” Kubrick explains. “In the first type the camera was mounted stationary to the set, so that when the set rotated in a 360-degree arc, the camera went right along with it. However, in terms of visual orientation, the camera didn’t ‘know’ it was moving. In other words, on the screen it appears that the camera is standing still, while the actor walks away from it, up the wall, around the top and down the other side. In the second type of shot the camera, mounted on a miniature dolly, stayed with the actor at the bottom while the whole set moved past him. This was not as simple as it sounds because, due to the fact that the camera had to maintain some distance from the actor, it was necessary to position it about 20' up the wall-and have it stay in that position as the set rotated. This was accomplished by means of a steel cable from the outside, which connected with the camera through a slot in the center of the floor and ran around the entire centrifuge. The slot was concealed by rubber mats that fell back into place as soon as the cable passed them.”

Kubrick directed the action of these sequences from outside by watching a closed-circuit monitor relaying a picture from a small video camera mounted next to the film camera inside the centrifuge. Of the specific lighting problems that had to be solved, he says: “It took a lot of careful pre-planning with the lighting cameraman, Geoffrey Unsworth, and production designer Tony Masters to devise lighting that would look natural, and, at the same time, do the job photographically. All of the lighting for the scenes inside the centrifuge came from strip lights along the walls. Some of the units were concealed in coves, but others could be seen when the camera angle was wide enough. It was difficult for the cameraman to get enough light inside the centrifuge and he had to shoot with his lens wide open practically all of the time.”

Cinematographer Unsworth used an unusual approach toward achieving his light balance and arriving at the correct exposure. He employed a Polaroid camera loaded with ASA 200 black-and-white film (because the color emulsion isn’t consistent enough) to make still photographs of each new set-up prior to filming the scene. He found this to be a very rapid and effective way of getting an instant check on exposure and light balance. He was working at the toe end of the film latitude scale much of the time, shooting in scatter light and straight into exposed practical fixtures. The 10,000 Polaroid shots taken during production helped him considerably in coping with these problems.

"Filmmaking" in the Purest Sense of the Term

To say that 2001: A Space Odyssey is a spectacular piece of entertainment, as well as a technical tour de force, is certainly true, but there is considerably more to it than that.

In its larger dimension, the production may be regarded as a prime example of the auteur approach to filmmaking — a concept in which a single creative artist is, in the fullest sense of the word, the author of the film. In this case, there is not the slightest doubt that Stanley Kubrick is that author. It is his film. On every 70mm frame his imagination, his technical skill, his taste and his creative artistry are evident. Yet he is the first to insist that the result is a group effort (as every film must be) and to give full credit to the 106 skilled and dedicated craftsmen who worked closely with him for periods of up to four years.

Among those he especially lauds are screenplay co-author Arthur C. Clarke, cinematographers Geoffrey Unsworth and John Alcott, and production designers Tony Masters, Harry Lange and Ernie Archer. He also extends lavish praise to special effects supervisors Wally Veevers, Douglas Trumbull, Con Pederson and Tom Howard.

The praise, it would seem, is not all one-sided. MGM’s post-production administrator, Merle Chamberlin, worked with Kubrick for a total of 20 weeks, both in London and in Hollywood, on the final phases of the project. A man not given to rash compliments, Chamberlin has this to say of the endeavor: “Working with Stanley Kubrick was a wonderful experience — a tremendously pleasant and educational one. He knows what he wants and how to get it, and he will not accept anything less than absolute perfection. One thing that surprised me is his complete lack of what might be called ‘temperament.’ He is always calm and controlled no matter what goes wrong. He simply faces the challenge with incredible dedication and follows it through to his objective. He is a hard taskmaster in that he holds no brief for inefficiency — and it has been said that he knows nothing of the proper hours for sleeping — but he is a fantastic filmmaker with whom to work. I have been privileged to work very closely with David Lean on Doctor Zhivago,with John Frankenheimer on Grand Prix, with Michelangelo Antonioni on Blow-Up and with Robert Aldrich on The Dirty Dozen — all terrific people and wonderful filmmakers. But as a combination of highly skilled cinema technician and creative artist, Kubrick is absolutely tops.”

From my own relatively brief contact with the creator of 2001: A Space Odyssey, I would say that this praise is not over-stated, for Stanley Kubrick, film author, epitomizes that ideal which is so rare in the world today: Not merely “Art for the sake of Art” — but vastly more important, “Excellence for the sake of Excellence.”

2001: A Space Odyssey was selected as one of the ASC 100 Milestone Films in Cinematography of the 20th Century.

Herb A. Lightman was the longtime editor of American Cinematographer.

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.