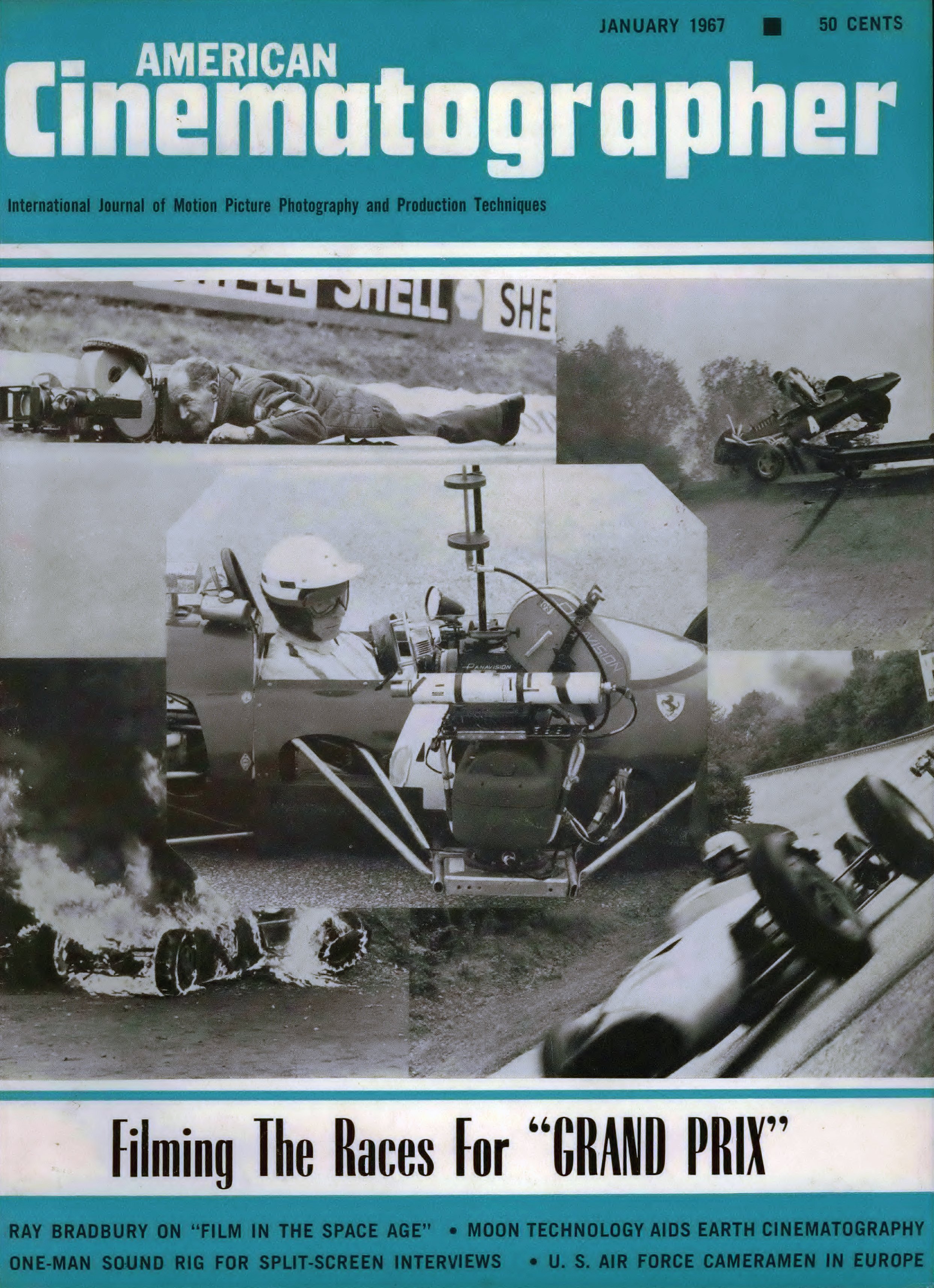

Photographing the Races for Grand Prix

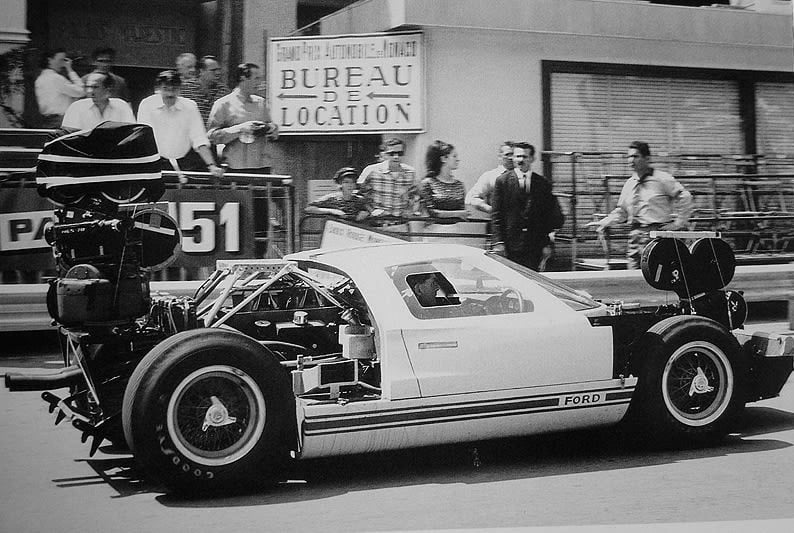

Radio-controlled Super Panavision cameras, microwave viewfinders, a helicoptering cameraman and daredevil drivers combine to film the most exciting auto race of them all in the actual locales where it happened.

By John Stephens

Second-Unit and Helicopter Cameraman, Grand Prix — MGM

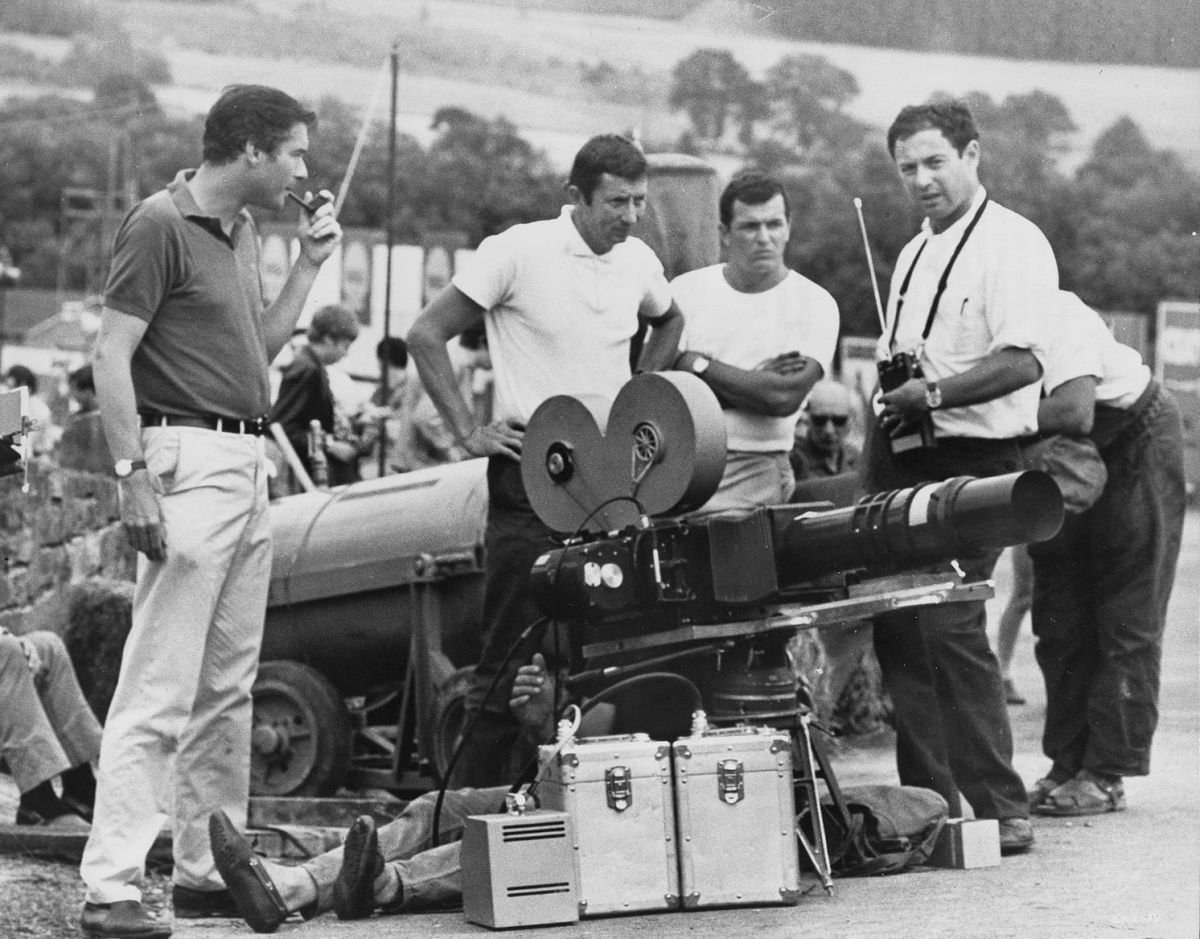

It all began about a year ago when Roy Clark and I were working as camera operators for director of photography James Wong Howe, ASC on John Frankenheimer’s film Seconds, at Paramount Studios.

Frankenheimer was then preparing to direct Grand Prix, and because he knew I had worked with many unusual camera rigs on snow-skiing, water-skiing, surfing and underwater film assignments, he figured that I might be able to come up with some ideas on how to photograph the exciting racing sequences that would make up a major part of his next picture.

The main challenge would be to rig some sort of camera car that could keep up with the racing cars going at up to 180 miles per hour while actually running on the circuits in Europe. Also required would be a special camera rig and pan-tilt head that could withstand the shock of the tremendous vibration these cars develop at such high speeds.

We kicked various ideas around all through the shooting of Seconds, and one day Frankenheimer came to me and said: “Johnny, how would you like to be the cameraman going at 180 miles per hour in a specially built camera car while photographing the actual race drivers on the Grand Prix circuit?”

I said: “You’ve got to be joking. It would scare the hell out of me!”

Actually, while the assignment was professionally very tempting, I didn’t know whether I wanted to do it or not. I couldn’t visualize going that fast — especially if I would have to ride backwards to photograph cars behind me. I knew nothing about racing or race cars and had probably been to about two races in my entire life. The whole thing appeared to be too much of a challenge and the more we talked about it the more impossible it seemed.

Frankenheimer said that he expected to cover all of the various circuits in Europe and that he also wanted to have as many as twenty cameras shooting each race. He also wanted to be able to communicate with the operators of all of these cameras individually. Each idea he came up with was wilder than the one before. I told him I’d think about it.

The Lure Of The Challenge

I did think about it and, after more discussions with Frankenheimer I went home and drew up plans and sketches of how I thought such a specialized camera car should be built, including camera mounts, remote control facilities and communications.

The first thing I knew I was involved in it up to my ears. The challenge was simply too much to pass up. And it was some challenge! For example, the schedule called for five months of location shooting during which we would be filming at six different European tracks. We would have to complete shooting of each track right on time in order to get to the next one. It would be necessary to film each race as it was actually going on — which meant uncontrolled action — and retakes would be impossible. Scenes with the actors and actresses would be staged right in the pits during the actual races.

Buck Rogers Technology Applied To Film

Just at that time I read with fascination about the Mariner II space vehicle that was sending back pictures from Mars through many millions of miles of space by means of microwave. I recalled, also, that while in the Navy, I had worked at El Centro with radio-controlled airplanes and had mounted cameras on the wings of aircraft as well as on parachutes. It seemed to me that if there could be mounted on a racing car a Panavision 65mm camera that could be completely controlled by an operator riding in a chase car or in a helicopter, some fantastic scenes could be photographed.

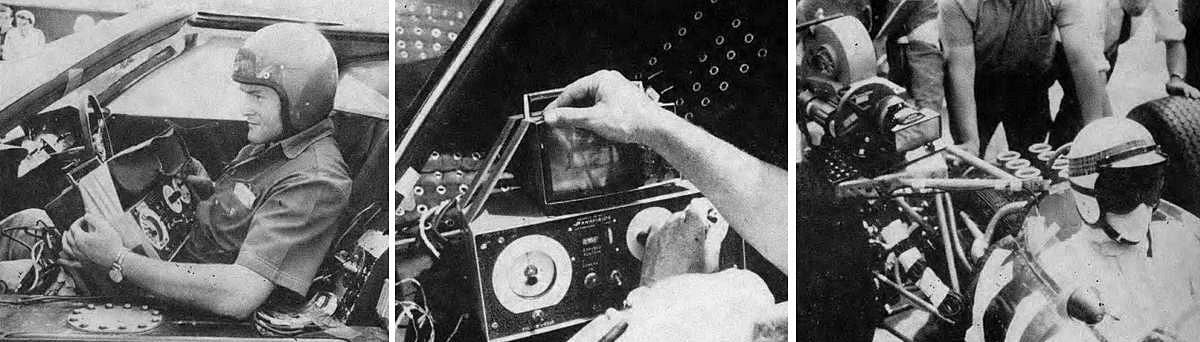

It would require a kind of “Buck Rogers” rig — one that would include electronic control of the pan and tilt head, follow-focus, footage counter, change of aperture, on-off switch, etc. It would also have to include some sort of electronic viewfinder so that the remote operator could see exactly what the camera was recording while the scene was being filmed. It called for a blending of space-age electronics with motion picture technology. I took the problem to Gordon Enterprises and they showed me an electronic pan-and-tilt head manufactured by the Pelco Company of Los Angeles for the purpose of tracking missiles. It is a special heavy-duty head weighing about 70 pounds and the rate of pan or tilt can be speeded up or slowed down by remote control as required.

By way of electronic viewfinder equipment, Gordon also provided a Cohu television camera, an extremely rugged, vibration-proof, shock-proof mechanism about 3" in diameter and 14" long of the type attached to missiles as they are launched to send pictures back to earth of what the missile actually “sees” in its flight through space. I was sure this would be just the kind of TV camera needed because of the beating it would have to take at such high speeds. A Sony receiver with a 5" screen would serve as viewing monitor.

Assured, now, was the operator’s capability of viewing a scene by means of microwave while working as far away from the camera as one mile. Still needed, however, was a highly sophisticated radio-control system for operating the various functions of the camera itself. For this I was referred to the Jacobson Engineering Company in Hollywood. Irving Jacobson said that no such device was currently on the market, but he agreed to build a 9-channel radio-control unit to suit our needs. Gordon Enterprises later combined this with their microwave unit and the Sony monitor into a seven-pound package measuring only 10" long, 6" wide and 3" deep. This miniature console was compact enough for me to hold it in my lap and regulate all functions of the camera by remote control while strapped into a chase car moving at high speed.

The Camera Equipment

Realizing that unusual demands were to be made upon the cameras involved, I went to Bob Gottschalk, president of Panavision Inc., and discussed with him what would have to be built and developed to meet our needs.

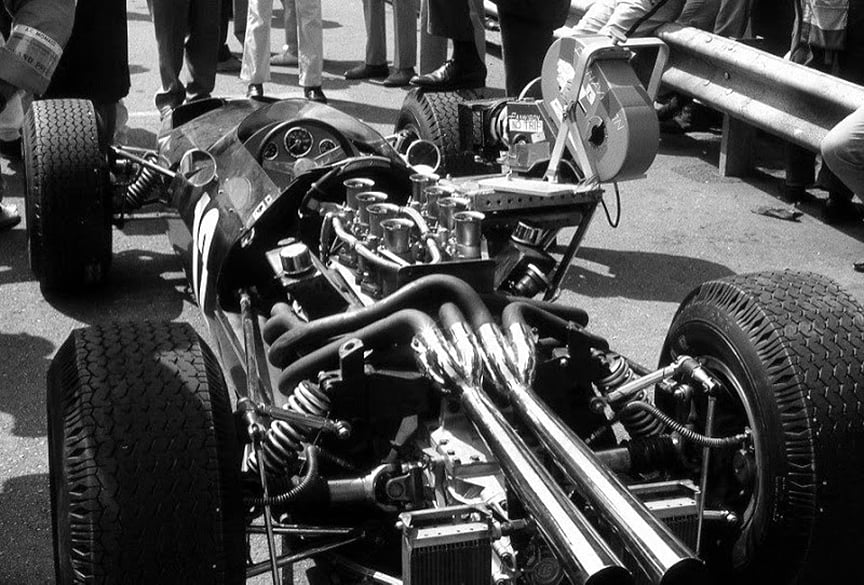

Part of the problem facing us was the incredible amount of centrifugal force that would build up when the cars went around curves at high speeds, plus the violent vibration that went with it. To avoid having cameras and magazines flying off in mid-curve, Frank Scalatti, machinist and technician at MGM Studios, built special cage-like braces around the cameras that could be securely bolted to the mount.

Another problem had to do with the G-forces exerted upon film inside the displacement chamber of a magazine when a fast-moving car takes a curve. The film is forced against the inside of the magazine causing a braking action and resultant jamming of the camera. To forestall such trouble, Panavision installed free-moving flanges inside the magazines so that no matter how much lateral pressure was generated, the film, forced against those flanges, would continue to flow normally. In order to get some of the extreme wide-angle shots which John Frankenheimer required, Panavision came up with its 17mm Hyper-wide, a lens of high-resolution and almost negligible distortion.

For the opposite effect, Panavision developed a 1000mm telephoto lens with a speed of T/6.3 and an angle of 3 degrees.

The Super Panavision 65mm hand-held camera, carrying its normal 500-foot magazine, was the camera selected to be mounted on the race cars, but these cameras were also adapted to be quickly convertible to standard shooting with a 1,000-foot magazine.

Panavision also devised a special feedback read-out for the follow-focus system so that the operator could tell at all times at what exact distance the camera was focused.

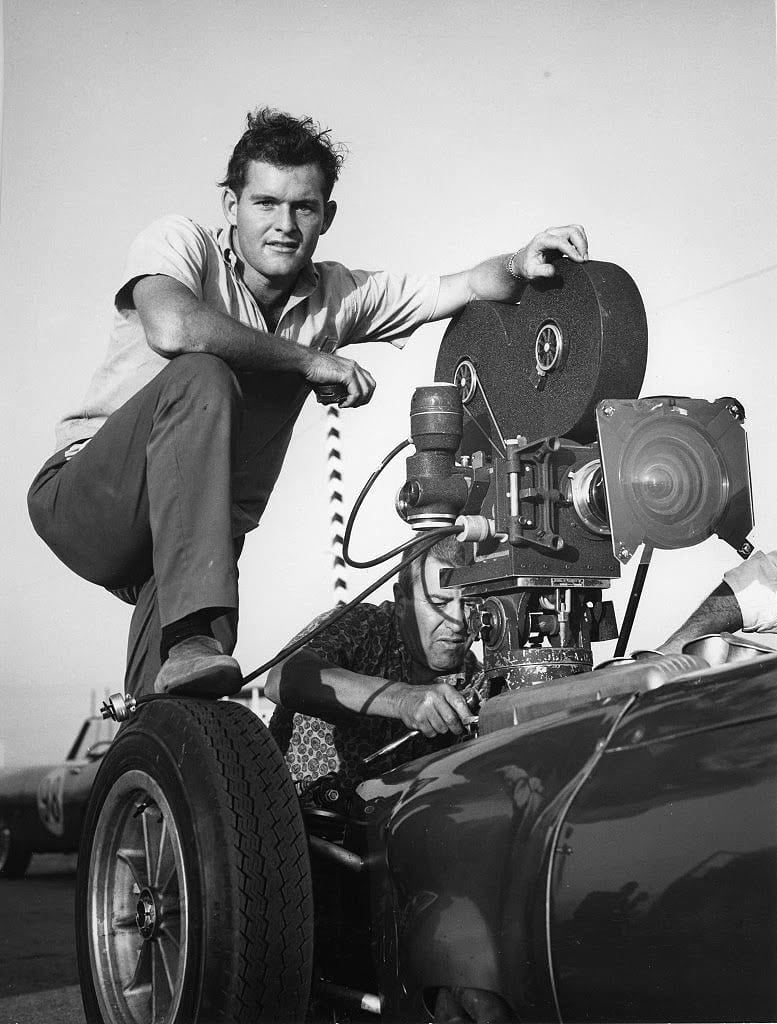

Mounting the Cameras Onto the Race Cars

One of the major challenges was that of designing and constructing camera mounts that would hold the equipment securely while not interfering with the efficiency of the racing cars. We didn’t know how much additional stress and strain we dared put on these cars. When you mount 120 extra pounds of weight three feet out on one side of a car you can pretty well expect that something’s got to give on the other side.

Bill Frick, the world’s foremost designer of camera mounts, was engaged to tackle this problem. He was directed to design many different types of mounts because Frankenheimer wanted each race to be photographed in a different way. Each mount was specially tested to withstand a stress of more than 300 pounds.

During test filming, Frankenheimer would show Frick where he wanted the lens to be for a particular shot and Frick would start cutting and pounding metal tubes right on the scene. Within about 20 minutes he would have constructed a sturdy mount that would take the normally skilled grip three or four hours to build.

The Shakedown Tests

After almost four months of developing and constructing the many various pieces of equipment, the time finally came to put them all together and give them a practical testing. The site selected for the trial run was Riverside International Raceway, with veteran racers Phil Hill and Bob Bondurant doing the driving. The camera was mounted on a Shelby Cobra and a Ford GT-40 was used as the insert camera car.

These first tests at Riverside revealed that we had many problems. The film in the camera continually jammed because the wind blew so hard against the beltdrive that it stretched it. This left too much slack in the take-up and a jam would occur. This was also when we found out that revolving plates would have to be placed inside the 65mm magazines because of the friction caused when the car took high-speed curves.

The Pelco electronic pan-tilt head had to be re-designed to pan at three times its normal speed — which meant that special gears had to be made.

A Topaz Powermaker converter was installed in the Cobra to convert the 12-volt DC current into 110 AC power. This gave me the 300 watts needed to run the Sony monitor and also served to operate the Pelco head. The Panavision camera and the TV camera were both run off of 30-volt DC battery current. It took three days to make these tests, but we learned many valuable things about the equipment. As a result, another four weeks were devoted to making necessary changes.

The Final Preparations

A different camera car was to be used for the next series of tests. A Ford GT-40 was decided upon by John Frankenheimer and drivers Hill and Bondurant, who would be driving the car at speeds up to 180 miles per hour all through the actual filming of Grand Prix in the months to come. The Ford GT-40 is a much faster car than the Cobra, with a closed cockpit for the driver and cameraman. In actual use, it also proved to be a better performing car in terms of the extra weight it had to carry by way of cameras, TV and electronic equipment.

Since the first tests at Riverside in February, Jacobson Engineering and Gordon Enterprises had refined their microwave and radio-control units down to final form, and adjustments had been made to the Pelco head. With nine channels available on the radio-control transmitter, we could:

• Pan and tilt the electronic head at different speeds. (6 channels to operate.)

• Follow-focus from 3 feet to infinity. (1 channel.)

• Change aperture. (1 channel.)

• Turn the camera on and off. (1 channel.)

The Ford GT-40 was brought to MGM Studios for the following fittings: a Topaz power unit to be installed, 30-volt battery mounts made, and wiring from front to back for all electronic equipment. The Panavision camera, TV and Pelco head were installed in a Formula car. This complete unit was mounted beside the driver.

The microwave television transmitter and the radio-controlled receiver were mounted under the hood. The antennas for both of these units were mounted on top of the camera in order to be out of sight of the lens even when the camera panned 360 degrees. 30-volt battery belts were designed by Panavision to run the cameras, as well as the microwave unit. An additional Topaz Powermaker, along with a 12-volt battery, was also installed in the nose of the Formula car to operate the Pelco head. On-off switches were placed on the dashboard so the batteries would not run down. A rheostat was also installed on the dashboard to change the speed of the follow-focus. The camera was mounted at eye level, three feet to the right of the driver and at a 45-degree angle.

Four more days of testing now followed at Riverside track with all phases functioning. The GT was a perfect choice for a TV receiving station and camera car. Each company was there to supervise its own equipment because of the unusual way it was being used. The Motorola radio company was also represented there because of the radio helmets they and Bell Toptex had developed for us. With these radio helmets the cameraman in the camera car could communicate with the drivers in the Formula-1 cars. Director John Frankenheimer could also direct the drivers into special scenes from a helicopter. The cameras no longer jammed, the film took up properly for its 500 feet, the radio-controlled equipment all worked. We now felt a little more informed about all our new gadgetry. At this point everything was working — true — but I now began to dread that day when, in the middle of a shot with 10,000 extras lined up along the race track, an electric wire might short out. How long would it take me to find it? Where would I begin?

We made sure there was a schematic of each piece of equipment we had. Three sets were made up; one for the electronics man (who was to be hired in England), another set for me to study and the third to be tucked away for safe keeping. Heavy duty cases were built, filled with foam rubber, to transport 185 pieces of radio controls, television gear, antennas, wiring, batteries, Pelco heads, TV lenses, 24 Motorola radios (each with two stations in FM), earphones with microphones built in, and a 25- watt Base Station with portable antenna. Each item was listed and placed in special compartments in each of 24 cases. This equipment was packed in special compartments in each of 24 packing cases.

Also included were 12 standard Super Panavision 65mm camera units, four Hand-held Panavision cameras (completely modified with fiber-gear controlled magazines, eliminating all belt drives), one Panaflex (likewise modified), three Mitchell AC cameras and three Mitchell BFC cameras. In addition to this 65mm equipment, there were three anamorphic 35mm Arriflex cameras.

The Master Control box to be used by the operator inside the Ford GT-40 consisted of:

• An electronic follow-focus meter. This enabled the cameraman to follow focus from the control box and see on the meter the exact focus. The camera can be positioned any place around the Ford-GT with a motor connected to the lens. A cable connected between the lens and meter transmits a pulse from the lens to meter indicating footage.

• A footage-counter indicated at all times the exact amount of film running through the camera. By timing the footage counter the cameraman could also tell if the camera was losing speed.

• On-off switches for three separate cameras.

• A control “joystick” for panning and tilting the Pelco electronic head.

• A rheostat to speed up or slow down the pan and tilt head.

• Switches to turn on the TV camera, Topaz Powermaker and follow-focus.

Fourteen 30-volt, 7-amp-hour battery belts, for use by operators while hand-holding the cameras, were included. These belts were also used inside the Formula I cars to operate cameras. 30-volt Sun-Gun lights were used at times connected to the electronic cameras on the race cars.

The Overseas Safari

All of the equipment was shipped from MGM Studios and received in Rome by Gordon Meagher, chief technician for Grand Prix. Camera Operator Gian Franco Maioletti assisted Meagher in organizing the equipment when it arrived. Otto Nemenz, Panavision’s lens technician, and my first assistant on the picture, checked out all the lenses carefully. Three large vans were constructed with built-in darkrooms, benches, shelves and air-conditioning. All of this equipment had to be organized and loaded into these vans within a week after arrival so that it would arrive in Monte Carlo by May 1. Meagher was responsible for keeping track of more than 600 pieces of equipment.

Meanwhile, Lionel “Curley"' Lindon, ASC, had been given the assignment of overall director of photography on Grand Prix. He was a natural for it, not only because of his technical skill, but because he has been an all-out auto racing enthusiast for the last 25 years. A member of SCCA and the California Sports Car Club, Curley drove Austin-Healeys and MG’s in racing competition around Southern California from 1948 to 1959. Between races he had managed to win an Academy Oscar for his color cinematography of Around The World In 80 Days. Designated as second-unit cameramen were Jean-Georges Fontenelle, Yann Le Masson and myself.

The Cameras Roll

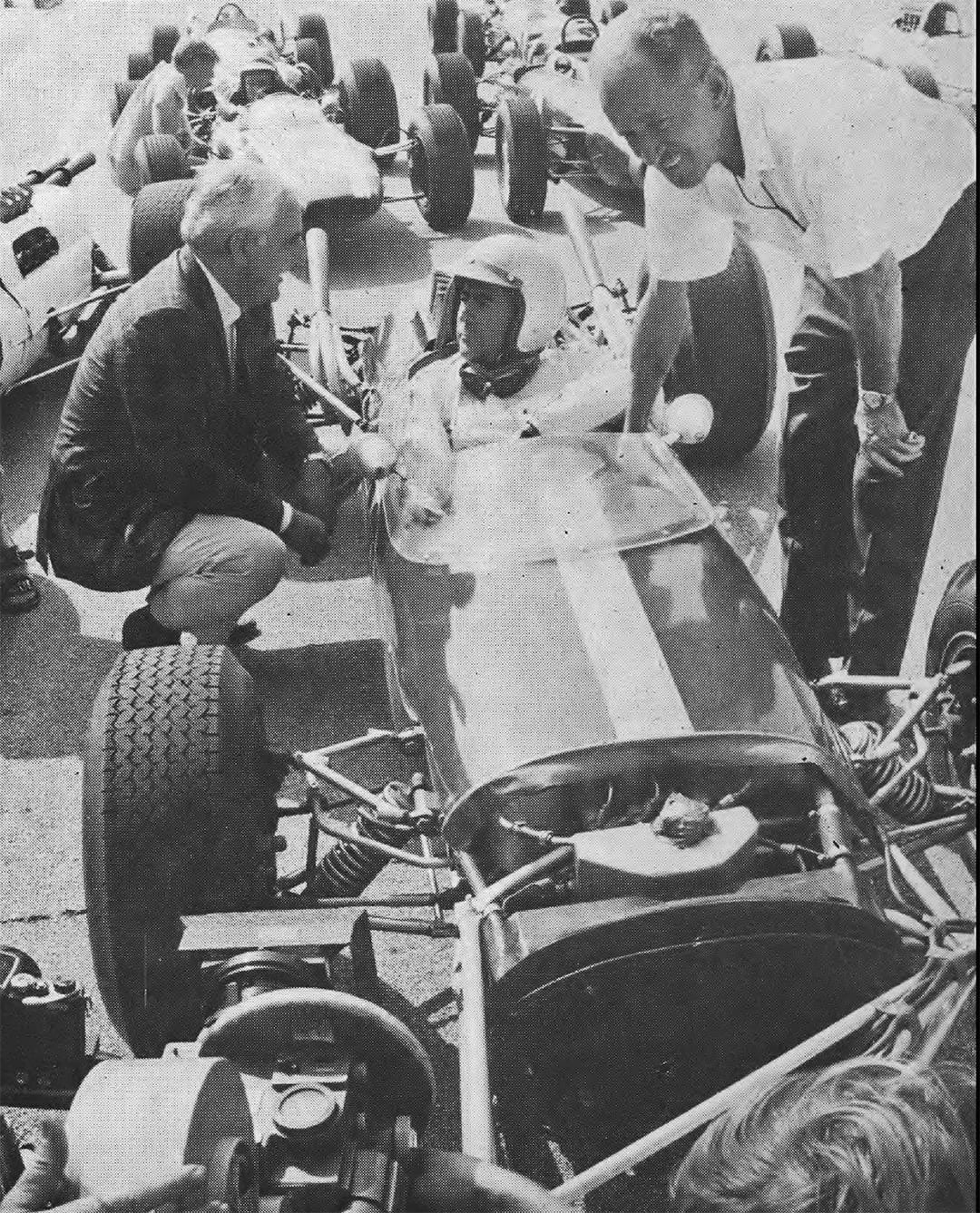

When actual shooting got underway in the foreign locations, it became apparent that getting Grand Prix onto film was going to be an exceptionally difficult task — and it turned out to be exactly that. John Frankenheimer had said that he wanted complete realism, which meant that there could be no process or matte shots in the picture—all of the scenes and backgrounds were to be authentic. Also, the actors playing race drivers would be required to actually drive their own cars.

James Garner had gone through the Shelby racing school at Riverside, where he was trained by Bob Bondurant and John Timanus. He then completed the course at the Jim Russell school along with Montand, Bedford and Sabato at Snetterton Race Course in England.

Jim Russell, aided by eight mechanics, rebuilt 16 Formula-III Lotus 1.5 liter cars into three BRM’s, three Ferraris, two AAR’s, two Brabhams, two Lotuses, three Japanese Yamuras and one Maserati.

Special fiberglass shells were made up to look like the identical cars that were to be driven in this year's race. Russell, along with special effects experts Milt Rice and Bob Bonning, had to adapt these new fiberglass bodies, as well as figure out where the tail pipes were to go. This was the year the 3-liter cars were to run — cars with 16 cylinders, 200 mph plus. Anything could happen.

Up until the time the tests and practice runs began at Monte Carlo, Rice and Bonning didn't know for sure what the engines of the cars would look like, because each factory kept the looks of its car a tight secret until the first race.

Each of the Formula-I cars was wired separately so that a camera could be switched from one car to another without having to go through a lot of changing of wires and cables. Starting from scratch, it would take about 3.5 hours to rig one of these cars for photography.

First, Bill Frick would build a mount wherever the director might want it to be on the car. There were at least seven positions where a camera would work nicely. For one sequence we even had a mount rigged to a front wheel of Yves Montand’s car. When he turned his steering gear the camera turned also. The 17mm Hyper-wide lens showed part of the wheel, too.

The Pelco electronic pan-tilt head would be secured to the mount and the camera would be aligned on top of the head. The microwave transmitting antenna and the radio-control receiving antenna would go on top of the camera to be out of the way. I would connect the microwave transmitter and the radio-control receiver in the nose of the car.

The Cohn TV camera “viewfinder” would be aligned with its lens about 3.5" off to the side of the taking lens of the film camera. On a pan shot I would pre-set the parallax for the farthest composition. Then, on a piece of clear plastic over the monitor, I would draw an outline of the actor’s head where it should line up when I panned around to the closeup.

Realism At Any Price

The Panavision 65mm hand-held camera weighs 38 pounds with a 500-foot roll of film in the magazine. We had four of these and they were used, not only mounted on the race cars, but also on shoulder-pods for hand-held work during the races. This compact equipment enabled the operators to work in close and move around easily. Frankenheimer had specified that no tripods were to be used for the atmosphere scenes and he employed a considerable amount of hand-held photography during trials as well as during the actual races. He needed mobile cameras so that the operators could move freely in the pits, but move fast to avoid getting in the way of the drivers or mechanics. Realism was injected into Grand Prix by these authentic grabshots of the drivers coming in for gas or to change wheels at each one of the courses: Monte Carlo; Spa, Belgium; Brands Hatch, England; Zandvoort, Holland; Clermont-Ferrand, France and Monza, Italy.

All of the scenes in Grand Prix, including the interiors, were shot in actual locations. Many times Curley Lindon had to light rooms only 10 feet square with 8-foot ceilings.

There barely seemed to be room enough for the 65mm Super Panavision camera and crew, let alone actors and lights. It appeared to be an almost impossible task, but Lindon managed to get some of the most beautiful photography ever seen on the Cinerama screen. His scenes filmed inside the Palace Hotel in Monte Carlo, for example, are really fantastic.

Grand Prix was filmed in a documentary style, with dramatic scenes staged in and around the pits during the actual races at all of the tracks. While one camera crew was shooting the professional actors, four other operators (equipped with Panavision Hand-held cameras and battery belts) would be roving around the pit area grabbing crowd and atmosphere shots that would fit into the story.

Frankenheimer used 18 separate camera crews at Monte Carlo. These were made up of German, French, English, Turkish, Dutch, Italian and Swiss cameramen—plus the American crew, which included Curley Lindon, Frank Scalatti and myself. At first there was a little problem of communication, but we were lucky in that several of the foreign operators spoke good English. We would have liked to be able to place one of these in each crew, but there were only enough of them to allow us to have one English-speaking technician in each of 10 crews. Even so, it is amazing how well we worked together after a while, with a real spirit of teamwork.

MGM technicians Frank Scalatti and Gordon Meagher worked with Curley Lindon day and night to organize the 18 foreign crews and teach them how to use the Panavision 65mm equipment, which they had never operated before.

It seems that the French are in the habit of calling a power strike about once a week, and they pulled one at the particular moment when Scalatti was getting ready to charge 55 batteries for the next day’s shooting. At 9 o’clock that night Meagher was trying to find the driver of the generator truck, an almost impossible task on a Friday night in Monte Carlo. He ended up hot-wiring the truck so that it could be driven to the camera department, where lines were strung from the truck to the battery room. The batteries were charged and Meagher was the hero of the day.

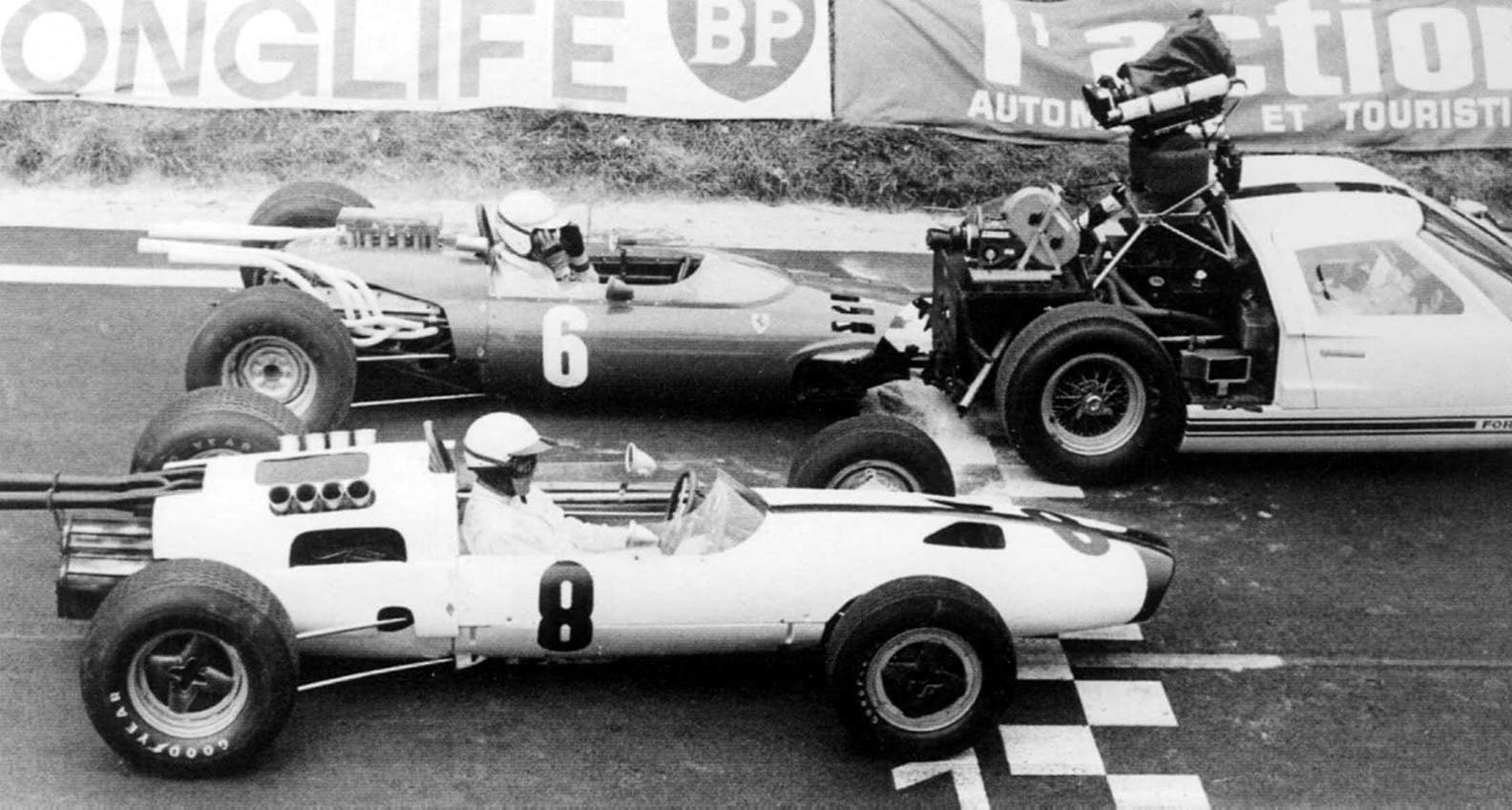

Automated Camerawork At High Speeds

During one actual race day at Monte Carlo, we had three cameras mounted at once on the Ford-GT. One was a Panavision 65mm camera mounted forward and tied off for a point-of-view shot. Another similar camera, also tied off, was mounted directly in back to photograph the cars behind us. The third camera, remotely controlled, was mounted on the Pelco head in the center of the Ford-GT at a height of about 2 feet. This carried a 100mm lens for tight closeups of the drivers. The front and back cameras carried 50mm lenses to get wider-angled shots. I could control the picture on the top camera precisely by watching the monitor, but the console also carried on-off switches for the front and back cameras.

Special rigging made possible the use of two electronic cameras at the same time, and I could switch from one to the other.

The Pelco electronic pan-tilt head was capable of panning a full 360 degrees when mounted on a Formula-1 car, and this came in very handy for some of the lengthy continuous shots which Frankenheimer wanted to make without any cuts.

For example, there was one sequence for which the camera was mounted two feet to the right of Garner’s head and about 45 degrees toward the front. Garner is driving at 130 mph side-by-side with Anthony Sabato, who is driving a Ferrari. The camera pans right to fill the screen with Sabato’s car as he tries to pass Garner. Sabato edges ahead and I pan with him, changing focus from 6 feet to 20 feet, so that the camera is now shooting through the front wheels of Garner’s car. Garner tries to get around Sabato, slip-streaming for a while. He finally sees his chance and passes Sabato on the right. I pan the camera to a tight shot of Garner, changing focus from 20 feet to 3 feet. As the duel continues, Gamer looks over at Sabato on his left with that special little smirk peculiar to racers. Now he finally edges to pass Sabato and, as he does so, the camera pans straight back to a shot of Sabato’s car framed by Garner’s rear wheels. During the last pan, focus was changed from 3 feet to 20 feet. The entire sequence runs for 2 1 /2 minutes without any cuts.

We had a hectic situation with the radio-control while filming in Monza. I was riding in the GT behind James Garner, who was driving his Formula-I car at a speed of 130 mph with the camera mounted on his right side. I was maneuvering this camera by radio-control when it suddenly started panning and tilting for no reason at all. This happened time and again and it took us a whole day, with the aid of special radio tracking equipment, to figure out that someone was flying a radio-controlled model airplane on our frequency in a park about a quarter of a mile away. Frankenheimer sent an assistant over to buy the airplane from the kid so that he wouldn’t fly it anymore.

Correcting The Horizon Line

When a car was driving on a banked track, Frankenheimer wanted the camera to be able to tilt laterally so as to correct the horizon line. Otherwise it wouldn’t actually appear that the car was driving at a 45-degree angle. This constituted a problem until we thought of mounting the camera sideways on the Pelco head and then turning it around so that the lens pointed forward. In this way we were able to get our lateral tilt—and a more realistic effect on the screen. I would simply tilt the camera sideways going into the bank, then correct it again as the car came out.

The same set-up was used on the Formula-1 cars. For example, one scene began on a 3-foot closeup of Yves Montand as he passed a couple of cars on the flat area of the track. At about 100 yards before he entered the bank, I panned the camera straight forward, pushing the radio-control button to change focus from 3 feet to 20 feet. At about 30 feet before he started up the bank I used the joystick control on the Ford-GT console to tilt the camera laterally and correct the horizon line. He was still slip-streaming other cars. Then, as he dived down to pass them on the flat, I straightened the tilt on the camera.

Air-Borne Camera Crane

I had been put in charge of all helicopter photography on Grand Prix, and for these sequences we used the Panaflex 65mm reflex camera equipped with a 90mm-250mm zoom lens and mounted on The Nelson Tyler vibrationless helicopter mount. This is by far the smoothest mount available and has the zoom and follow-focus controls right in the hand-grips.

The special ear pieces developed by Motorola to be enclosed in a helmet made it easy for me to maintain complete two-way radio communication with the pilot and with Frankenheimer during the entire helicopter filming. I could also talk to the actors in the cars and tell them to slow down or speed up or whatever was required in the shot.

One of the trickiest helicopter shots was made at the Spa, Belgium, track with Frankenheimer riding the Alouette-111 jet helicopter with me and helping out with the follow-focus. We had a French pilot named Gilbert Chomat who was obviously one of the best in Europe for this type of work.

The scene was to start with a closeup of James Garner in the cockpit of his Formula-1 car traveling at 140 miles per hour. Once having established the identity of the driver, we were to zoom out as the helicopter pulls away to show Gamer’s car passing two or three other cars on the track.

The pilot flew the helicopter down to within 10 feet of the moving car and I racked the zoom lens out to 250mm for the closeup. At f/11 with the 250mm focal length I only had about a foot of depth-of-field to play with, so everything had to be right on the button. I kept talking to the pilot:

“In a bit closer... slower — a little slower... perfect, perfect — hold it right there!”

As he eased off on the throttle, Garner was centered in a full-frame closeup. I held my breath for 5 seconds and then hit the zoom. It started moving wider from 250mm to 90mm—which I knew would take a total of 7 seconds. After counting off 4 seconds I knew that the zoom lens must be at about 130mm, and I told Chomat to slowly ease up and away. Frankenheimer changed focus from 10 feet to 12 to 15 to 25 to infinity, as we pulled up to 3,000 feet and showed Garner passing the other cars. Naturally, we had to make several takes on this scene to make sure there would be no perceptible bump where the zoom eased off and the helicopter pull-away took over.

Working 10 to 15 feet away from the cars on other shots, we were able to get closeups of the drivers’ faces, the car wheels, etc. It was a bit spooky for the drivers having the helicopters working so close to them at high speeds. Obviously they didn’t have as much confidence in the pilot as I did.

A Little Rain Must Fall At Spa

Belgium, after the race started, it began to rain very hard. We never figured we’d be able to use any of that footage because all of our previous racing scenes had been filmed with the sun shining. But it continued to rain for the rest of the week, which meant that Frankenheimer had to rewrite the whole sequence to include the rain. We discarded most of the sun scenes we had shot and continued to film in the rain. The most exciting footage in the picture is that showing cars skidding along at 170 mph, throwing up 100-foot roostertails behind them that drown the cars in back. It’s especially exciting from the helicopter because you can see how the cars are able to maneuver in order to avoid this roostertail.

One of the biggest thrills of my life was when Phil Hill drove me in the Ford-GT camera control car while chasing those Formula-1 cars in the rain. Waterproof covers were used to keep the cameras dry, but we were going so fast that very little water stayed on the lenses.

It was in this situation that the Sun-Guns, mounted on either side of the camera, came in handy. Panning around to a closeup in that dull light, the tanned faces of the drivers tend to go very dark. The Sun-Guns, with dycroit blue filters in front of them, produced about a 40% fill that gave the skin a sheen and made the features visible. The Sun-Guns were tilted slightly inwards so that the light would hit the face just before the lens actually panned onto it. Spun-glass in front of the lamps made it possible to balance the light with the background.

Spills and Thrills

Some of the most exciting moments in Grand Prix are provided by the four car accidents included in the story. In order to stage these crashes realistically, special effects expert Milt Rice devised an air cannon that could catapult a car (minus its engine) a distance of more than 200 yards in 2 seconds at a speed of 100 miles per hour. The air cannon had a steel tank 7 feet long and 5 feet in diameter that held 500 pounds of compressed air and this was tied down and wedged into the ground so that it would not recoil when the air was suddenly released. The front wheels of the car were set straight and welded. A cylinder four feet long and closed at one end was welded to the rear of the car. This cylinder was fitted over a tube projecting from the air tank. Multiple cameras were then placed in several precarious positions to film the crash.

In one of these accidents, Yves Montand is supposed to get killed when he spins off the famous banked track at Monza after swerving to avoid an exhaust pipe that fell off the car ahead of him. He skids and hits the rail and the car is supposed to soar through the rail and explode while Montand is pitched out into the trees. The air cannon propelled the car through the rail. As soon as it hit, an air ejector tube in the car went off, throwing the dummy up into the trees. The car crashed and burst into flame. It was all very spectacular.

At Monte Carlo an even trickier accident was filmed. James Garner’s car is supposed to collide with Brian Bedford’s car. Garner careens off into the ocean, while Bedford goes up the side of a rock wall. Six cameras filmed the spin-out with one of Hollywood’s top stunt drivers, Gary Lofton, at the controls.

Then Frankenheimer wanted a point-of-view shot to show what Garner sees as he flips up and into the water. To get this shot, Gordon Enterprises had provided a special 35mm sky-diving camera mounted inside an underwater housing. The camera weighed nine pounds, held a 100-foot roll of film and was fitted out with an Arriflex lens mount so that we could use a 9.8mm Kinoptik lens. This wide-angle lens was positioned exactly at Garner’s eye level so that you could see the arms of the dummy on the steering wheel. The car goes through the chicane, hits the hay bales and flies out over the ocean. The whole world turns upside down and then the car hits the water. Wild!

For other cuts in this sequence, the air cannon was again used to propel a car in which was sitting a dummy that was a very good likeness of Garner.

After five months of steady filming in six different countries, we had exposed more than 850,000 feet of 65mm Eastman Color Negative. Along with some really spectacular action, the blood, sweat and tears of the entire cast and crew is on that film. But it was all worth it — because Grand Prix turned out to be a rather exciting movie.

You'll find related coverage on the film Ford vs Ferarri right here.

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.