Filming La Dolce Vita in Black-and-White and Widescreen

Production filmed in Rome reveals some interesting techniques employed by Italian cinematographer Otello Martelli.

By Libero Grandi

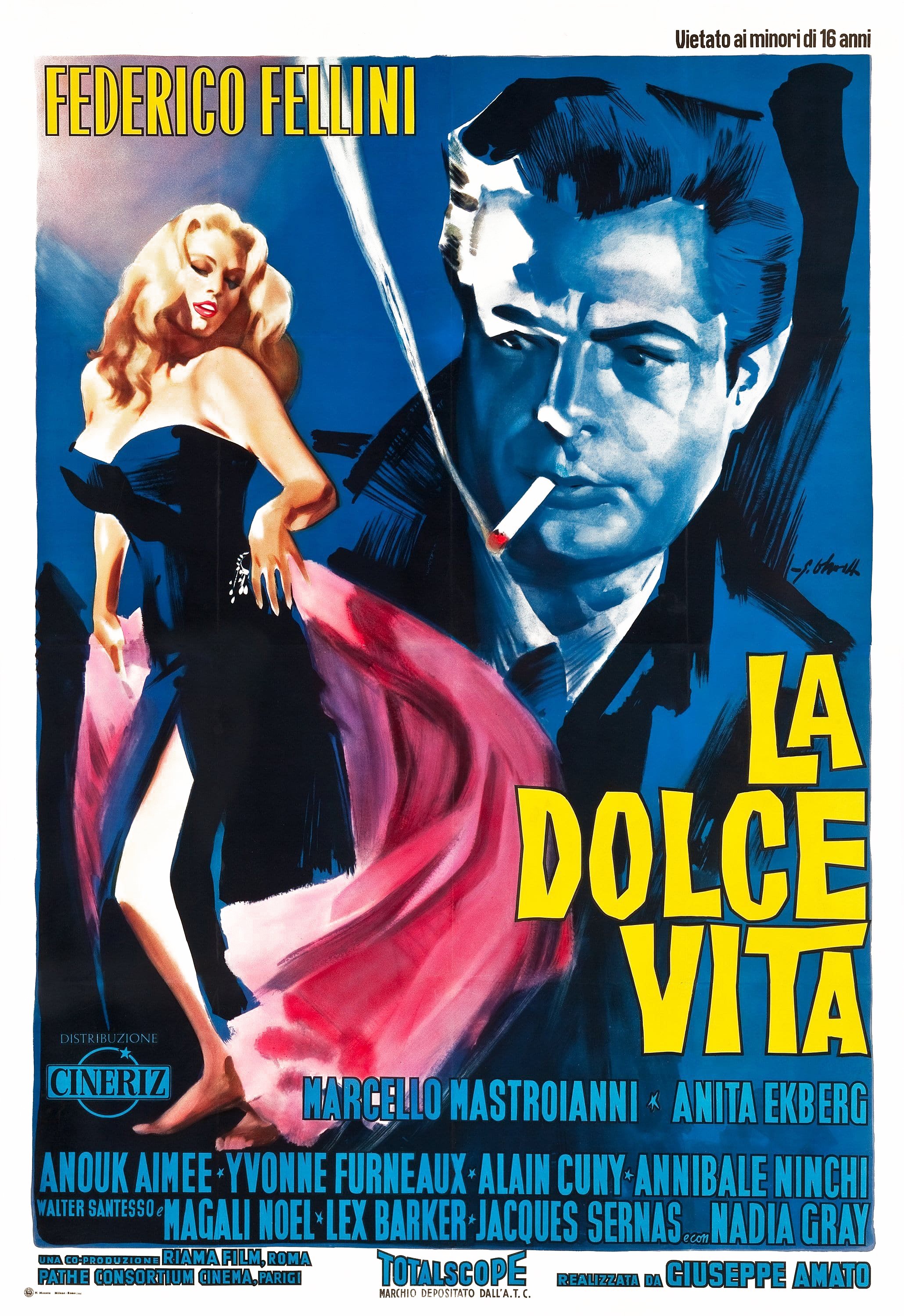

La Dolce Vita, the widescreen production directed in Italy recently by Federico Fellini, reveals a photographic technique so closely integrated with the subject matter of the story that it is almost impossible to discuss them separately. Cinematographer Otello Martelli, an old colleague of Fellini’s (the two collaborated previously on the award-winning productions, La Strada and Le Notti Di Cabiria), directed the photography of La Dolce Vita. Foregoing many of the established photographic rules, Martelli expresses in a key-tone all the various characters and events taking place in the film itself. His choice of lenses is often unique, too. Martelli used 75mm, 100mm, and 150mm long-focus lenses for closeups and two-shots in place of the 50mm lens generally used for making similar shots in CinemaScope.

Director Fellini wanted to give the story psychological depth by deliberately putting out of focus the middle and the background of many scenes, rather than use the pan-focus system which would have revealed the scenes in full depth. Also, when making pans and traveling shots in closeup, Fellini preferred the results of a 75mm lens — even though cinematographer Martelli was apprehensive of some audience reaction that would result from the disturbing effect of the images virtually dancing before one’s eyes on the screen. The result, however, turned out most satisfactory.

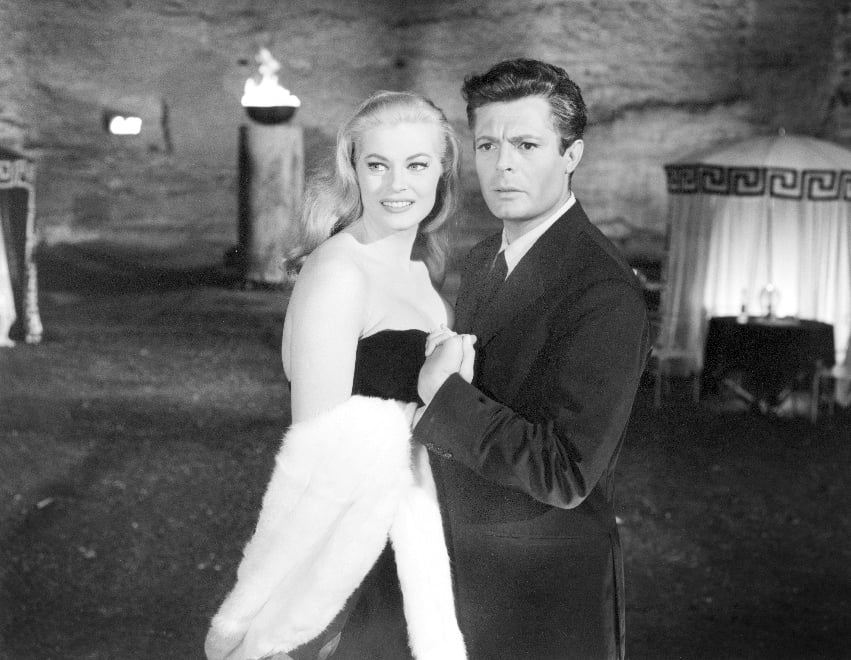

Where there are shots with dialogue between two actors (one in C.L. and the other in the foreground) the depth of field is quite limited because of the long focus lenses used; the focusing operation (during shooting) had to follow each actor in turn very carefully, throwing out of focus the actor who had just finished speaking and bringing the other into sharp focus. An example is the dialogue scene between Steiner and Marcello at Steiner’s house — the technique underscores their hopeless isolation.

The hazy background against which the actors play the sequence further points up their solitude — their incapability of reaching a common ground. Remarking on this, Martelli said: “Director Fellini has given the film individual style by deliberately distorting the characters and their surroundings, and also by their clear-cut figures.

A notable effect is the pictorial beauty of the dawn scenes in La Dolce Vita. Rather than marking the beginning, they symbolize an ending. Here the photography, in varying shades of gray, is cold and unemotional. Then as dawn breaks, and Anita Ekberg and Marcello Mastroianni are seen wading in the Fountain of Trevi (below), they awaken to reality.

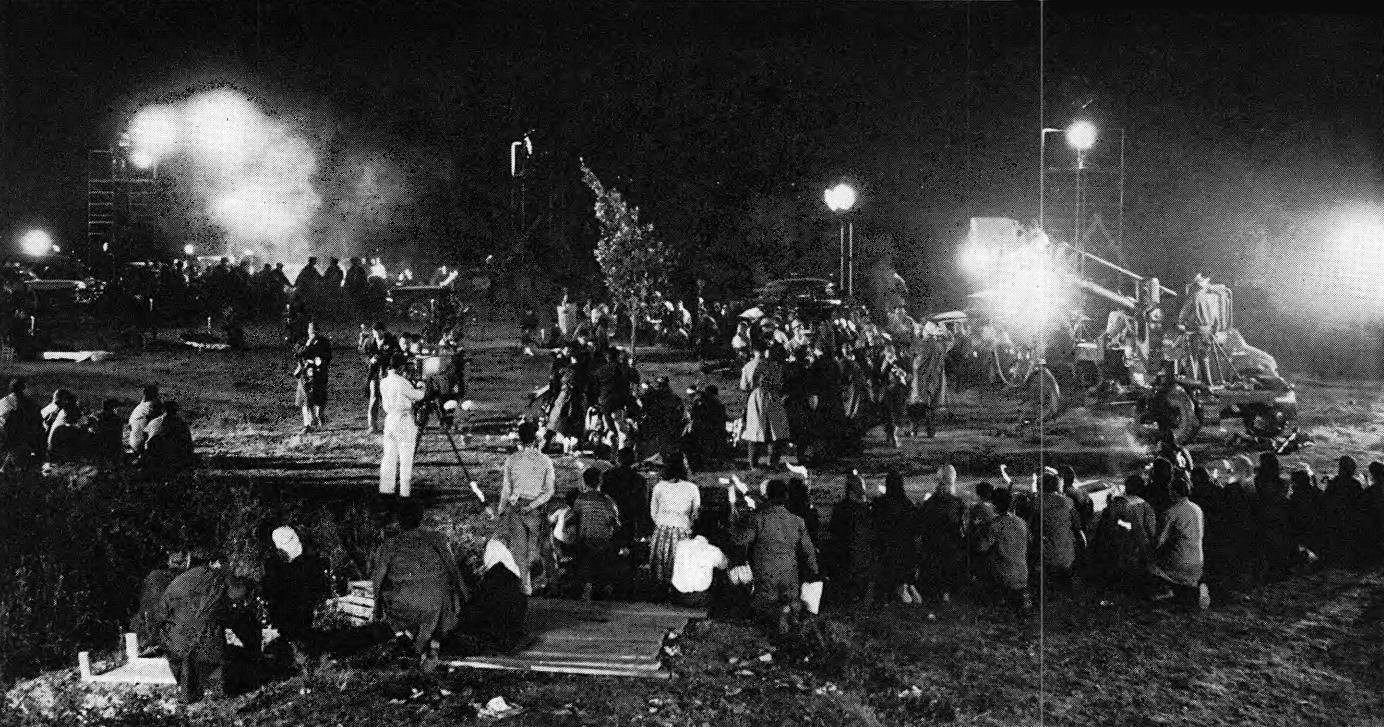

The dawn effect following the “miracle” sequence, somber in its photographic tone, exposes the disillusionment and misery that has overcome the hysterical crowd that had waited vainly through the night for the miracle to take place. Later, a dawn effect closes the final scene of a sequence depicting a night of dissipation and orgies by the disappointed people. Here the strong contrast of gray against the clear-cut figures dressed in black and white serve as a key-tone for the composition of the scenes. Then, when a young girl appears — symbolizing a last tentative hope — the lighting in the scene becomes a little brighter.

Many of the principal night exteriors covered large areas. To light them, extensive equipment was required. For the “miracle” sequence, 40 10,000- watt, 30 5,000-watt and seven “Brute” lighting units provided the illumination.

One scene, which required special consideration by Martelli, showed technicians of a television station photographing the various phases of the miracle. A sudden thunderstorm causes the projectors to explode, and the resultant smoke provided strong contrasts in black-and-white, creating a sinister atmosphere. And to heighten the pictorial effect, the blast of lights were directed toward the camera. Martelli, apprehensive lest this direct flash of light toward his camera create unwanted halos on the negative, made a number of exploratory tests prior to shooting this scene. The stationary lighting equipment of the television crew in the scene was regulated as to its incidence on Martelli’s camera lens, as a means of avoiding the halos. Moving lights in the scene — such as those of automobile headlights, etc. — were directly taken by the camera and recorded on the negative as horizontal halos, result.

By contrast, lighting and photographing actress Anouk Aimée was most difficult because of her small features, which required use of strong, flat light.

For this picture, via Veneto, Rome’s famous boulevard, was duplicated at the studio, although some night exteriors were shot in via Veneto itself. The latter scenes were photographed with fast DuPont Superior 4 negative so that only a few photoflood lamps hidden among the trees lining the boulevard were all that were required to amplify the existing light.

Commenting on his association with director Fellini, Martelli said:

“Fellini prefers unlimited frames, which invariably heightens the problem of lighting. Sometimes, also, he likes to shoot a scene with the camera negotiating a full 360-degree pan. Working with him on the set one must be quick, have progressive ideas, and a flair for improvisation as Fellini himself improvises — changing the script during takes, asking for the most daring techniques to achieve the desired effects.”

"For example, while shooting scenes of the arrival of Sylvia at Ciampino airport, Fellini asked that the camera be panned toward the plane standing ready for the takeoff and with the sun directly behind it. I made the shot, with its predominantly back lighting, apprehensive of the results. But as it so often happens when Fellini suggests some unorthodox shot, it came out surprisingly well on the screen.”

Shooting this picture occupied the better part of five months — from April to September — of which two months were spent shooting the night exteriors. Over 300,000 feet of DuPont Superior 2 and 4 negative was exposed for the picture with a Mitchell BNC camera equipped for 4-perf 35mm Totalscope widescreen photography. (The camera optics comprised of Cooke lenses plus the Totalscope anamorphic lens).

For the aerial shots made from a helicopter for the opening sequence of the picture, an Arriflex 35 camera was used with similar optics. More than 9,000 feet of negative was shot during this phase of the photography.

The combined negative footage was edited down to approximately 16,000 feet and the finished print has a screening time of three hours.

La Dolce Vita went on to earn four nominations at the 1962 Academy Awards, including Best Director, Best Original Screenplay, Best Art Direction-Set Decoration: Black-and-White, and a win for Piero Gherardi in the Best Costume Design: Black-and-White category.

Martelli died at the age of 97 in 2000, his other credits including seven pictures with Felinni, also including I Vitelloni, La strada, Il Bidone, Boccaccio '70 and Le notti di Cabiria.

On Feb. 8, 2022, Paramount Home Entertainment will release the film on Blu-ray. This edition will include a new introduction by Martin Scorsese, who shares his thoughts on the film and its indelible impact on cinema. The picture was restored in 2011 by Cineteca di Bologna at L’Immagine Ritrovata Laboratory in association with The Film Foundation, Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia-Cineteca Nazionale, Pathé, Fondation Jérôme Seydoux-Pathé, Mediaset-Medusa, Paramount Pictures and Cinecittà Luce.