Photographing All the President’s Men

Some unseen cinematographic techniques applied to the filming of a best-selling book about a crucial moment in modern American history.

This article appears as it was originally published in AC May 1976. Some images are additional or alternate.

By Gordon Willis, ASC

Director of Photography

All the President’s Men was photographed in Eastman color negative 5254. Ninety percent of the film was force-developed one stop. The format was 1.85-to-1. It was photographed with the Panaflex camera and Panavision spherical lenses.

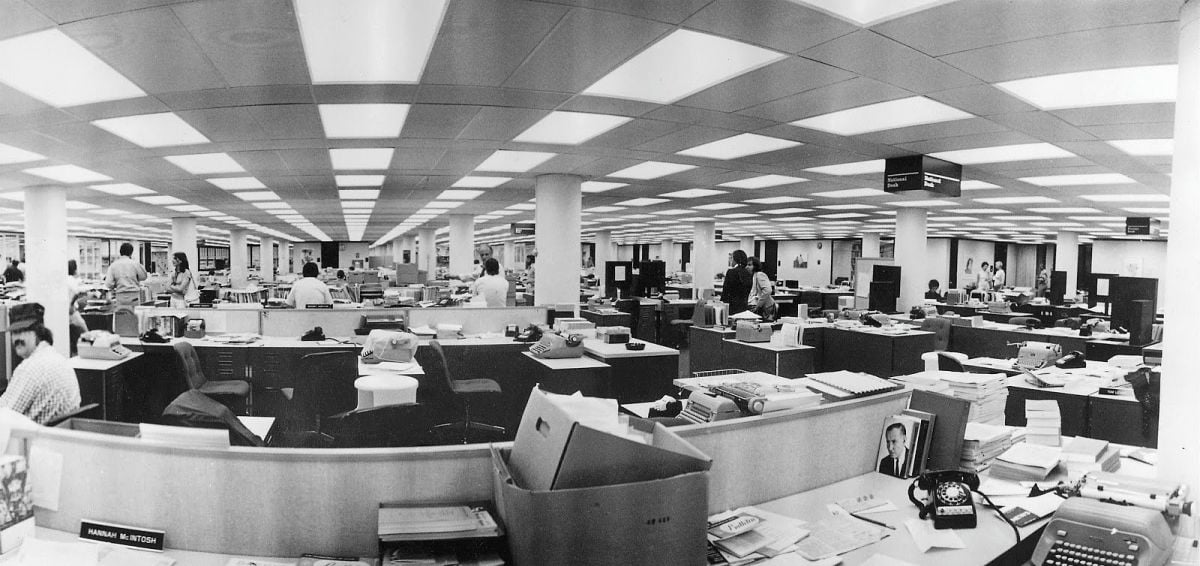

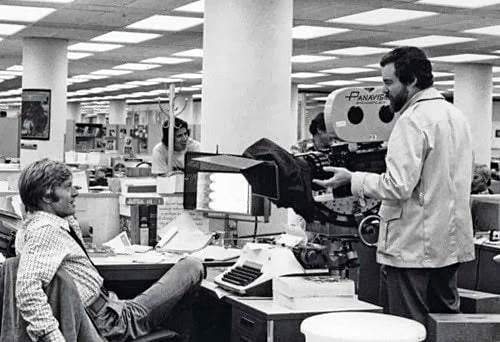

The primary set in the picture is the newsroom of the Washington Post. The real newsroom in Washington, D.C. would have been impractical to work in, as seventy percent of the picture takes place there. So it was decided to reconstruct the entire office complex at Burbank Studios in California.

In reality, the newsroom covers more than an acre of floor space, filled with desks, typewriters, files, tons of paper, and glass all over the place. It was no small feat reproducing this. George Jenkins, the art director, did a superlative job.

Prior to construction, the lighting was discussed at length and, since the real newsroom is lit exclusively with fluorescent lamps, my feeling was to keep it just that way. Fluorescent has a look all its own and I wanted to retain that look. So, fluorescent it was. The problem here was that we could not leave the ballasts that run the tubes on the stage, because of their inherent hum. So it took about 135 miles of wire to route the units away from the lamps and to the outside of the stage wall, where they were enclosed in air-cooled boxes. All in all, I think there were seven hundred fluorescents units and some fourteen hundred ballasts. Everything was carefully coded and, to the credit of George Holmes and the electrical department, the nightmare of loose connections, lost circuits and flickering lamps never came true.

The question of color rendition under fluorescent light is always just that — a question! I’ve never been concerned about fluorescent as fluorescent and I’ve left it just that way in past films. But there were too many scenes to be photographed on this set and I felt it would be very annoying to photograph that much material off-color. Not wanting to lose any stop with camera filters (which are not positive at any rate), I turned the correction over to the laboratory. We retained that hard fluorescent look, but took out the green.

The fun was yet to begin, however. On one side of the newsroom there were smaller offices that looked into the main room and all of them had a generous supply of windows and a generous supply of glass. I like glass, though, and found the multiple reflections fun to work with. Getting back to the windows. An eighty-foot backing was required to cover these windows, one for day and one for night. The problem here was that only twelve feet of floor space remained between the set and the stage wall. Within that space we had to hang two translight backings, on track, all the lighting, a white scrim between the windows and the backings, also on track, and a diffuser behind the backings, which was permanent. With this set up, we were able to slide the day or night backing in and out at will as well as add or remove the scrim. The scrim, however, was used only for day, in order to break down the detail of the backing, since it ended up so close to the windows.

Now comes the straw that almost broke this camel’s back. The lighting for the day backing was achieved by means of alternating 10K and 5K skypans. The night backing was lit selectively with smaller units on the floor. All of this lighting was tungsten. All of the lighting in the newsroom was cool white fluorescent. To bring the tungsten backing into correct color ratio with the fluorescent interior took a bit of doing. Since the lab was correcting, I had to find a color that would fall in line and, at the same time, look cooler than the interior. Since the picture started in Washington, I didn’t have much time to test and when I did find a color it had to be available in large enough quantities to cover eighty feet of background lighting. Whatever we tried kept coming up pink. The color that finally hit was pure Cyan.

To appreciate the amount of light required for the day backing, one should know that the exposure for the newsroom was set at T/4.5 and my preference for exterior related to interior has always been two to three stops overexposed. So the backing ended up at T/11. That’s being pushed through Cyan correction filters, diffusion, the backing and finally the scrim. It was too much light in too small a space. I didn’t like it, but short of removing the stage wall, I had no choice. My sense of humor about the backing was limited.

Perhaps the most difficult part of photographing All the President’s Men if not the most interesting, was the application of depth. There were times when backgrounds were just as important as foregrounds. That is to say, the environment could not be lost behind the actors, but had to be an integral part of the scene.

Our general attack on the problem was based on selective use of lenses and a series of split diopters. Now, split diopters are nothing new, but we used them in a fairly outrageous fashion. Zoom shots, for instance, as well as pans, etc. The people at Panavision were kind enough to build a 360-degree rotating diopter frame that enabled us to slide the additional elements in and out at any given angle — and in conjunction with a moving camera. The splits or halves were made especially without framework so they could be moved across the shot without incumbrance. A full series of lenses was used on the film and the stops ranged from T/1.2 down to T/11. The diopters were applied generally in the range of T/4.5.1 had a great deal of fun on the splits, especially the moving ones, and the system was extremely helpful when the requirements were there.

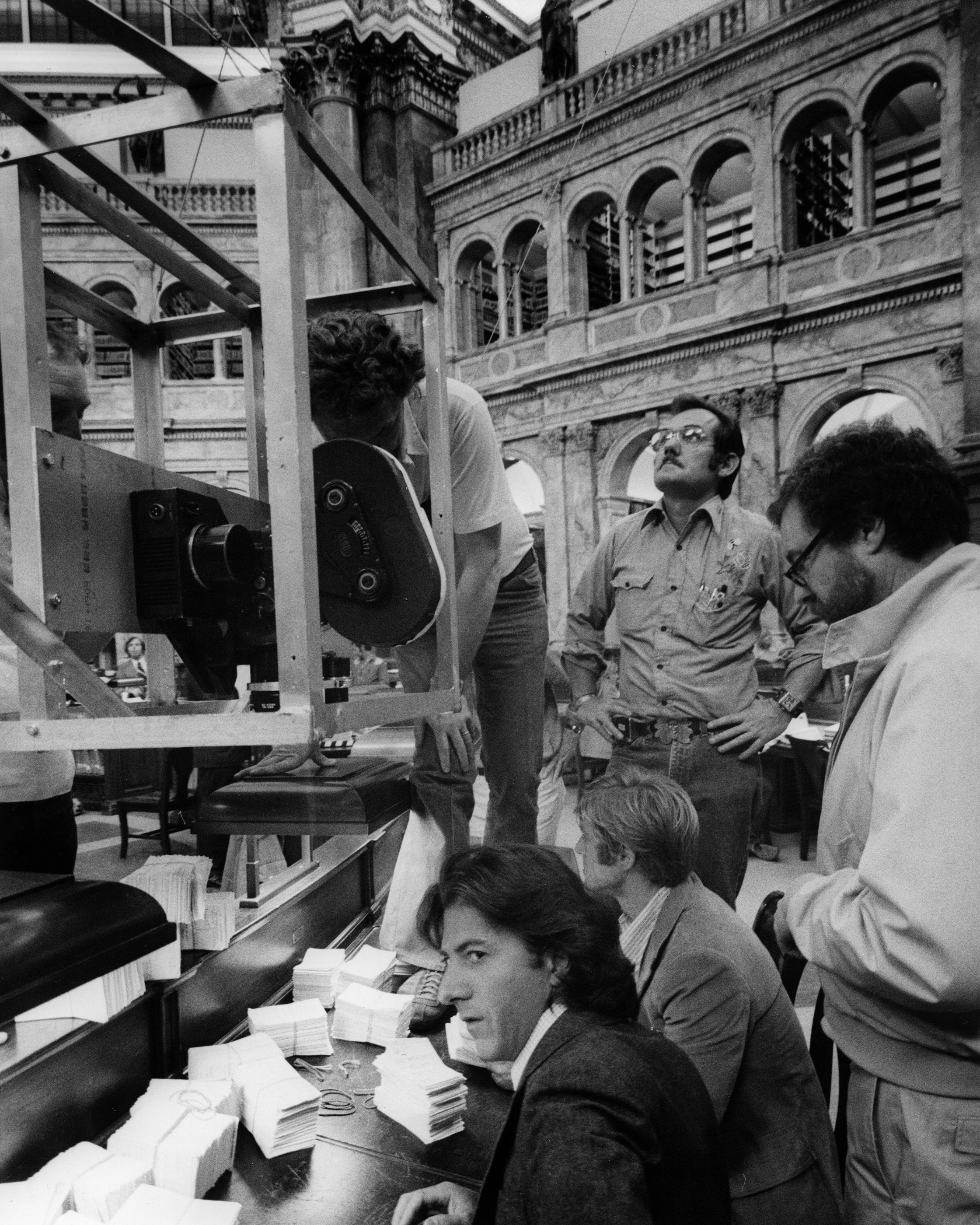

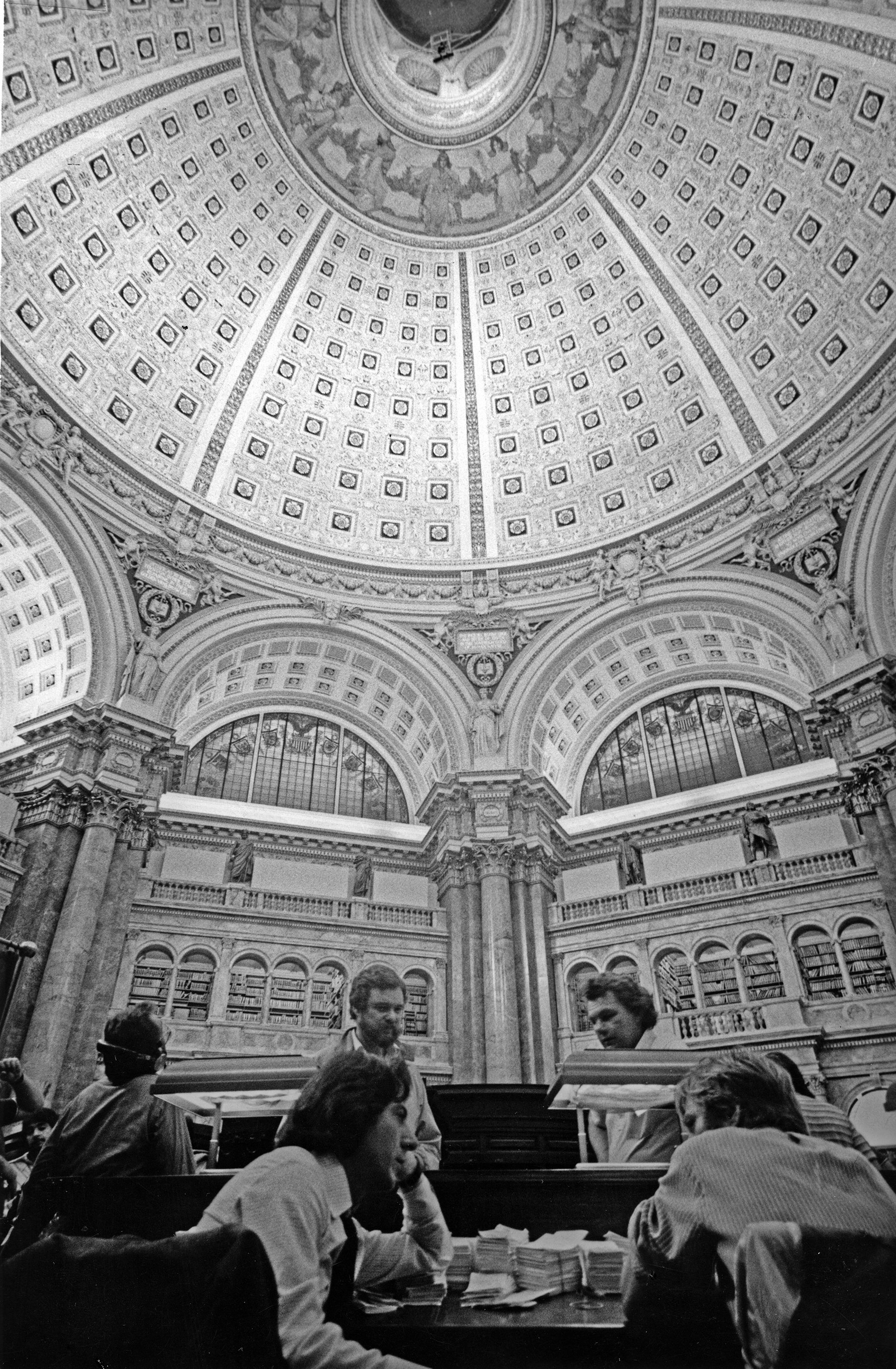

There is one last shot I might mention that could be referred to as out of the ordinary. It was made in the Library of Congress. It goes like this. We’re looking down on file cards, very close. The actors are thumbing through the cards. The camera slowly pulls away from the cards and heads for the ceiling of the Library, more than one hundred feet in the air. Arriving there, we have a full shot of the Library of Congress and the two small figures still thumbing through the cards.

When Alan Pakula, the director, approached me with this idea, I liked it, but liking it and doing it are two different things! I didn’t want to disappoint Alan if we couldn’t pull it off so I said, “It’s a maybe.” The way the shot was finally accomplished was with a remote-controlled cable system and a radio-controlled focus and switch system. Tag lines had to be used on the primary cable in order to correct the trajectory of the camera, as it did not start dead-center of the Library, but ended up that way at the top of the dome. The primary cable holding the camera was attached to an electric winch at the top of the Library and on cue it was slowly put into motion and raised to the top of the dome. The trick was coordinating the tag lines with the main cable. It took two tries on two different days to finally make it all come true. In its simplest form it was very difficult and Key Grip Bob Rose and his crew deserve a great deal of credit for their efforts. This shot, by the way, was made in natural lighting. A mixture of tungsten, and daylight from the dome.

I must say that Ray De La Motte, the first assistant cameraman, did an outstanding job at every level and accomplished one of the finest focus-pulling jobs I’ve ever seen. The problems he was faced with were enormous.

The picture was photographed in a graphic, poster-like quality that I felt was right for this story. It is a picture that can be run again and again. After all, it’s part of American History.

Behind the Scenes on All the President’s Men

Although the public had been saturated with information on the burglary, the cover-up and use of the FBI, IRS and CIA to harass those on the enemies list created by high offices of the Nixon Administration, Robert Redford had apparently sensed correctly that this was surface information. He believed the subsurface information to be highly dramatic and suspenseful, and book reviewers agreed.

They praised the “gripping power” of All the President’s Men (Chicago Tribune), called it a “political thriller” (Atlantic Monthly), and “one of the greatest detective stories ever told” (Denver Post). The New York Times called it “a classic.”

Says Robert Redford: “My first concept was for a small movie, costing less than $2,000,000. But Playboy ran excerpts from the book prior to publication. It became a hot item. Studios jumped into hectic bidding.”

Warner Bros, purchased screen rights for Wildwood Enterprises for $450,000 plus bonuses.

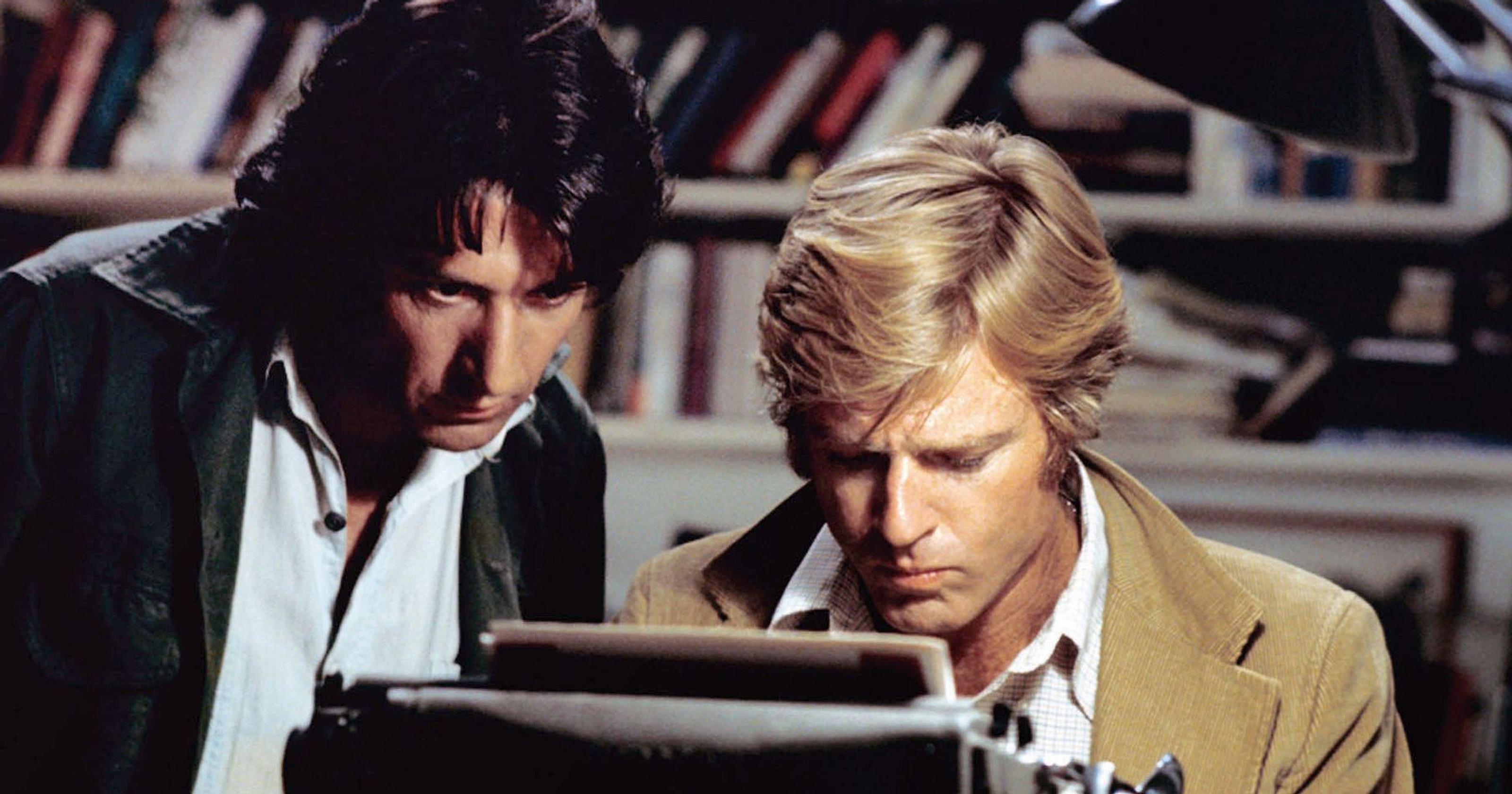

Originally Redford had intended using two unknown actors, since the reporters were themselves little known when the adventure began. But with costs so high for screen rights, story development, and set construction, it was apparent he would have to appear in the movie as Woodward — with another top star playing Bernstein — as insurance.

Warner Bros, gave Redford full freedom: “They agreed with my concept. They exhibited enormous faith in me by saying, ‘Make what you want’...and they stayed out of my hair.” Research basic to a possible Watergate film began in Spring, 1973, long before any certainty existed the film would be made, even before the book was written. Starting early in 1974 Redford spent much time in the Post newsroom, talked to reporters there and at The Boston Globe, Washington Star, and New York Times. Woodward says of Redford: “He is probably a better reporter than I am.”

Screenwriter William Goldman had accompanied Redford to Washington a year earlier for the preliminary discussions with Woodward. One of the prime challenges was to assure that the mass of factual data did not obscure the human values. Another was how to reduce 400 pages of book to reasonable screen running-time without sacrificing clarity of the narrative or character delineation. Goldman developed a structure which remained constant through several successive refinements of the screenplay.

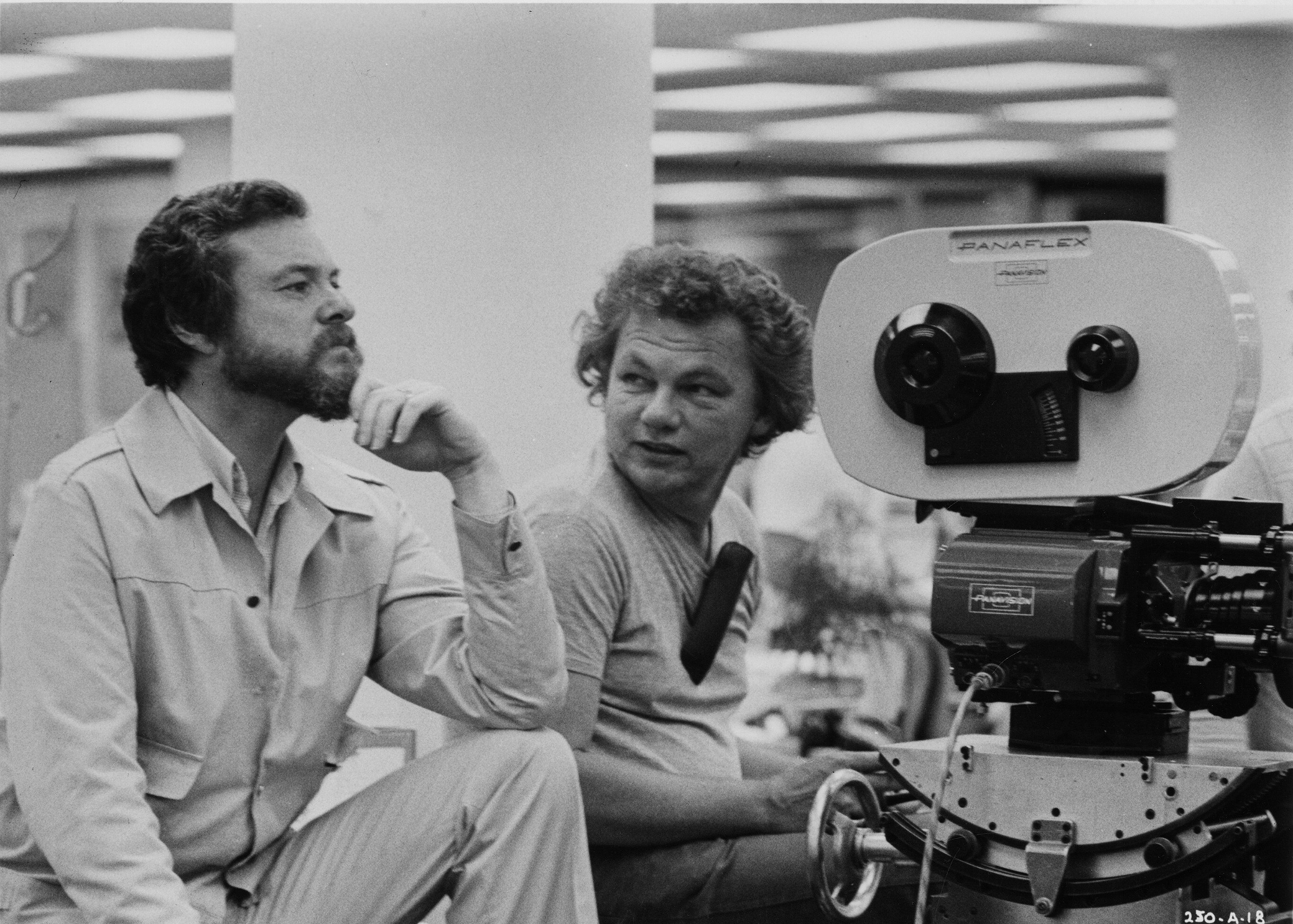

The people at the Post, especially Katherine Graham, publisher, and Ben Bradlee, executive editor, provided necessary cooperation. Alan J. Pakula came aboard as director. Dustin Hoffman, who had once hoped to acquire screen rights as a vehicle for his own company, was invited to play Bernstein, whom he resembles somewhat physically. Pakula descended upon the Post for many weeks of indoctrination into the mysteries of putting out a daily newspaper, plus an in-depth probe of the philosophical and professional attitudes which propelled the Post’s management into putting their corporate and individual professional futures on the line by publishing the Woodward-Bernstein revelations.

While about one-quarter of the movie occurs in the Post’s ultra-modern newsroom, early on Producer Walter Coblenz made the decision that it would not be possible to publish several editions daily and shoot a major photoplay simultaneously in the same place. He asked production designer, George Jenkins, to consult with the architects of the Post building, which was opened in 1971, and with its decorators. Armed with the original blueprints, Jenkins took over two adjoining sound stages at The Burbank Studios, knocked down the wall between them, and constructed a 32,000-square-foot duplicate of the Post news facility so precise in scope and detail that when Ben Bradlee visited the set in California he gasped, “My God, I’m in my own office!” The 250 desks were specially manufactured copies of custom-designed desks at the Post, finished in shades of blue, green, red and black selected by the paper’s publisher, Katherine Graham. The graphics on the walls were identical to those at the Post. Imbedded in the flush ceiling, suspended eight feet above the floor, were over 675 electrical fixtures. The exact position of each reporter’s and editor’s desk in Washington was duplicated at the studio. Each desk at the Post was individually photographed so that the accoutrements of the trade — reference volumes, diaries, family photos, ash trays, gadgets, even extension telephone numbers — could be reproduced. The 60-plus teletypes all worked. More than 300 phones were connected to an off-stage switchboard. And around the perimeter of the room equal care had been given to recreating the reference library, the offices of Executive Editor Bradlee, Managing Editor Howard Simons, Metropolitan Editor Harry Rosenfeld, the giant communications center linking the Post to its worldwide staff, the nerve center of the Washington Post-Los Angeles Times News Service, and the quarters used by the sports, theatre, book review and other editorial departments.

Total cost of this single set: over $450,000.

Equal care was taken to achieve authenticity in costuming. Both Woodward and Bernstein gave the film’s costumers access to their personal closets, and the clothing worn by Redford and Hoffman is a fair representation of the reporters’ divergent tastes. Hoffman even carried in his pocket a wallet whose contents exactly duplicated the contents of Bernstein’s wallet — though this does not figure as a prop in the movie. The search was for the feel of authenticity as well as its appearance.

Even the trash is honest. For several weeks, the Post collected all its newsroom refuse in huge boxes — suitably labelled as “National News Desk,” “Foreign Desk,” “City Desk,” and so on — and shipped it to California where it was spread around the set.

Despite the fact that All the President’s Men is virtually a contemporary story, to the moviemakers it was a period piece, set in 1972–73. Calendars on the newsroom walls had to reflect actual dates tied to the specific scenes being played. Exact copies of the Post, the Washington Star and the New York Times were reprinted with the papers’ help, for each such date. Phone directories on the reporters’ desks, Congressional directories, magazines within camera range — all were the appropriate editions. For exterior scenes around Washington, no car later than a 1973 model could be seen.

Filming began May 12, 1974, in Washington, D.C., at such diverse sites as the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, where 1,500 socialites, including many highly-placed members of the bureaucracy, impersonated theatergoers. A deserted garage hidden among the highrise canyons of nearby Arlington, Va., served as the exterior of the garage where Woodward had his super-secret meetings with the informer known as Deep Throat. The interior was photographed 3,000 miles away beneath the ABC Entertainment complex in Century City, adjacent to Beverly Hills.

Other Washington scenes were lensed at Lafayette Park outside the White House (permission to film inside the White House was withdrawn mysteriously at the last minute after being approved), at the Capitol, the Treasury Department, FBI, Dupont Circle, the Sans Souci Restaurant (where Jason Robards, Hoffman and Redford did a scene at the table usually reserved for Henry Kissinger), at the Post and, of course, at the Watergate Office Building and Howard Johnson’s Motor Lodge directly across the street.

The burglary was restaged exactly as it happened and exactly where it happened. The movie burglars entered via the same door the real burglars had taped open not once but twice — thereby virtually inviting capture. They invaded the same suite of sixth floor offices occupied in 1972 by the Democratic National Committee. And across the street at Howard Johnson’s an actor portrayed Alfred Baldwin, who was stationed as lookout on the same balcony after midnight June 17, 1972, while his colleagues bumbled their bugging mission at DNC headquarters. The filmmakers even hired Frank Wills, the Watergate security guard who discovered the robbery and sounded the alarm, to play himself.

Woodward and Bernstein’s apartments in the picture are reasonable approximations of their abodes when they were covering Watergate. The Library of Congress is the Library of Congress. Moving to California in late June, the company spent seven weeks in the ersatz newsroom, then moved to Los Angeles City Hall, whose exterior doubled for the County Justice Building in Miami, Fla., and whose interior represents the FBI headquarters in Washington. Other Los Angeles locations: a McDonald’s restaurant in Santa Monica, an apartment in Marina del Rey (Donald Segretti’s residence in the film), and Century City for the Deep Throat garage meetings.

Principal photography was completed September 23, 96 days after the cameras first rolled, almost three years after Bedford’s interest in the venture was first aroused. Moviolas and other editing equipment were moved into space adjacent to the Wildwood offices at the Burbank Studios, and Pakula and the film editor, Robert Wolfe, commenced the arduous task of editing the picture. But it would be a grievous error to stress too strongly the interesting logistics of a filmic undertaking of this nature.

All the President’s Men is many things. It is, first, entertainment, a newspaper story unlike any other ever made, a suspense story particularly terrifying because it is true, because it is current, and because the victims of the conspiracy are the very people seated in the audience viewing the picture.

Redford calls it a howdunit about a whodunit. It tells how the relatively inexperienced and always vulnerable reporters defied tremendous and frequently ominous opposition from sources of great power, persisting in their search for the truth about who did what to whom in the pastiche of politics and crime identified under the umbrella label “Watergate.”

Pakula and Willis later re-teamed for Comes A Horseman (1978), Presumed Innocent (1990) and The Devil's Own (1997).

In 2019, All the President’s Men was included in the ASC’s roster of 100 Milestone Films in Cinematography of the 20th Century. Learn more about this list here.

You'll find much more about Willis here.