Ford v Ferrari: Lap of Honor

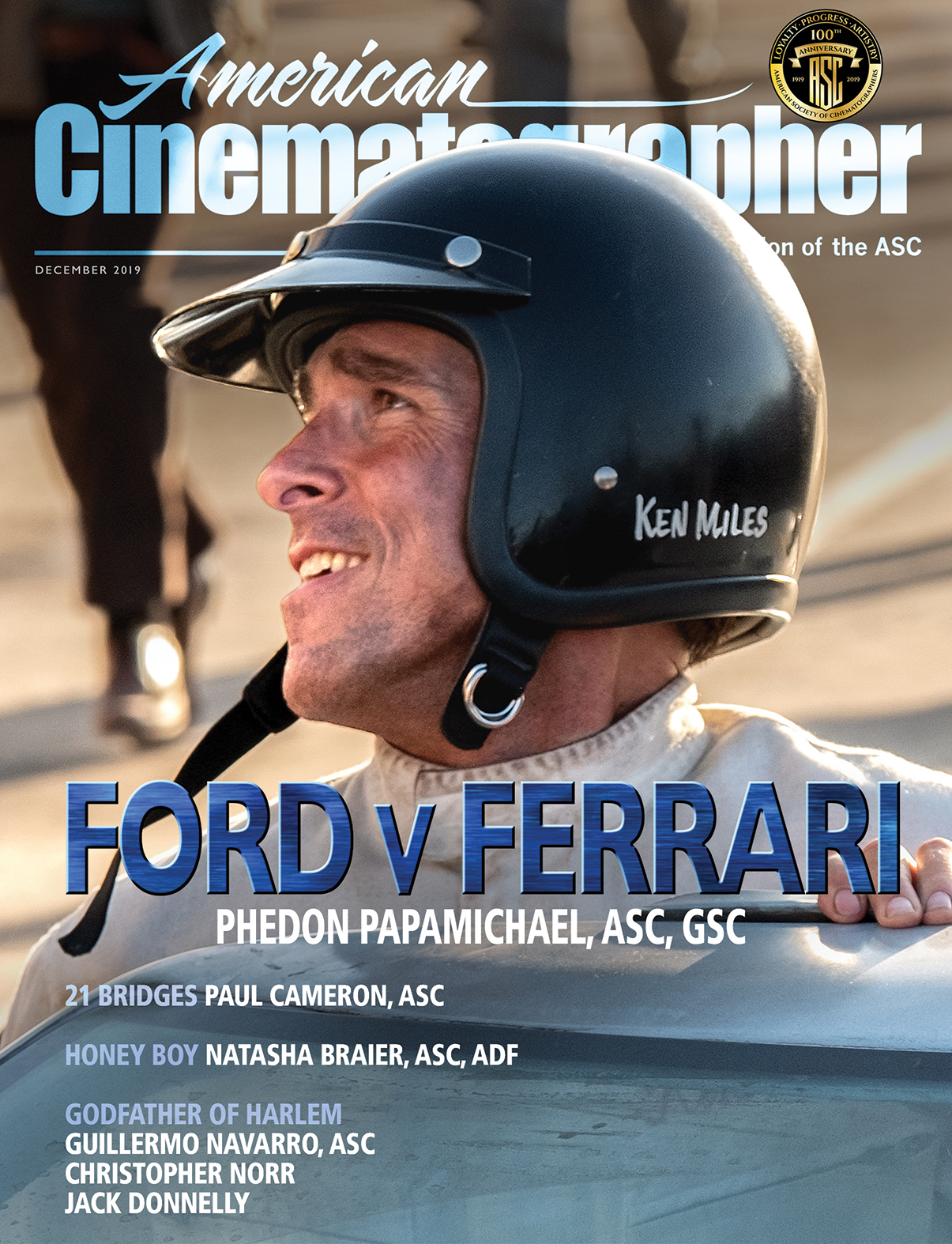

Phedon Papamichael, ASC, GSC helps director James Mangold re-create the road to and through the historic 1966 24 Hours of Le Mans auto race for this period drama.

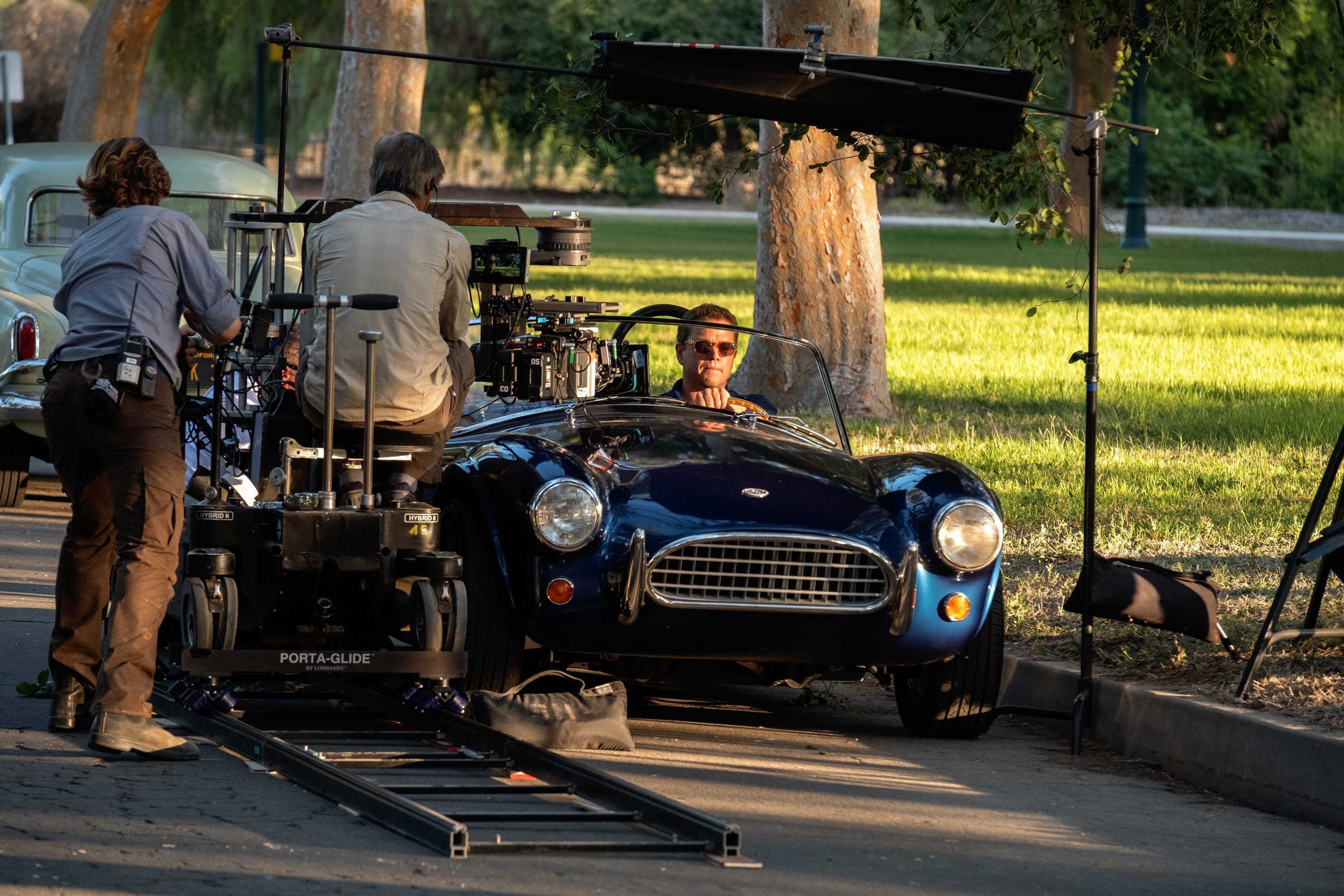

Unit photography by Merrick Morton. All images courtesy of 20th Century Fox Film Corp.

Ford v Ferrari marks the fifth feature collaboration between director James Mangold (interview here) and cinematographer Phedon Papamichael, ASC, GSC. Their previous movies have covered a broad range of genres, including horror (Identity, AC May ’03), musical biopic (Walk the Line, AC Dec. ’05), Western (3:10 to Yuma, AC Oct. ’07) and action comedy (Knight and Day). With their latest, they tackle a buddy dramedy set against the titular competition between two iconic carmakers, and Ford’s mission to develop the automobile that eventually won the grueling 24 Hours of Le Mans race in 1966.

The cast features Matt Damon as automotive innovator Carroll Shelby, and Christian Bale as mercurial driver Ken Miles. Hewing closely to actual history, the movie’s plot — as well as the visually rich milieu of 1960s auto racing — offered the filmmakers a great cinematic opportunity: to bring audiences into the cockpit and give them a sense of the driver’s experience.

Mangold and Papamichael built their visual grammar around that concept, shooting close to the action with mostly wider anamorphic lenses specially adapted by Panavision to work with the production’s Arri Alexa LF cameras. Key exterior locations included racetracks in California and Georgia, and runways at airports in Agua Dulce and Ontario, Calif. In Europe, the filmmakers also made pit stops in Monaco and the town of Le Mans.

“We had to be very economical and fast throughout, since we had a tight 64-day schedule,” Papamichael notes. Making that possible was a top-notch team that included camera operators P. Scott Sakamoto and David Luckenbach, first ACs Cary Lalonde and Craig Grossmueller, gaffer Michael Bauman, key grip Ray Garcia, and DIT Lonny Danler. Second and splinter units were led by Igor Meglic, ZFS and Cory Geryak, respectively. Second-unit director Darrin Prescott, stunt coordinator Robert Nagle and precision driver Allan Padelford also made crucial contributions.

AC recently caught up with Papamichael, who shared the following recollections of the production.

In the Driver’s Seat

Phedon Papamichael, ASC, GSC: We wanted to show the races from the point of view of Ken Miles so the audience would experience the races mostly from the cockpit. Action is not just about swooping shots, big wraparound moves or tracking aerials. If you’re not emotionally connected to your hero for all the little beats of this roller coaster, you just disconnect — it becomes boring.

We were inspired by classic racer films — like Grand Prix [1966] and Le Mans [1971] — that were made with more limited technical abilities. Jim and I chose to use old-school tools and techniques that were more in tune with that period. We wanted the majority of the coverage, the majority of the close-ups, to be from inside actual moving cars in order to feel the light changes and see the G-forces on Christian’s face, and to experience the proximity to the other cars that [were] tracking so close. All of that, plus the road vibrations transmitting through the camera and the immersive sound design, helps convey the roughness and intensity of the ride.

I decided in early testing that hard mounts without vibration isolators would convey that experience the best. And for our car-to-car work, we discovered that we needed to be low and close to communicate what it feels like to be in this death trap, loaded with fuel and doing over 200 miles per hour. Whenever possible, we included asphalt in the composition; seeing it streaking by helped to convey the velocity.

At the Willow Springs race early in the movie, we had four cameras on Christian, on hard mounts, all close-up at different angles, and we just sent him out there to do laps, with the other racers all around him. Ray Garcia used Black-Tek suction cups, which made mounting the cameras easy and quick. It is all real: the speed, the proximity, the mechanical stunts unfolding in the background — it all happened, and it’s all tied into his close-up coverage. It’s so much better for the actors to actually physically experience this.

We made extensive use of a ‘Pod-Car,’ which is an actual race car riding on its own tires, but with an extended chassis so that a ‘control-pod’ can be mounted at the front, when the camera is looking back at the actor behind the wheel, or in the back, when the camera is looking forward over the actor’s shoulder. The Pod-Car is controlled by the stunt driver.

We also had a ‘Frankenstein’ car, which is essentially a custom-built race car that’s set up for rigging cameras in multiple positions. This was the best tool to keep up with our Ford GT40s and Ferrari race cars. It allowed us to go around high-speed corners inches away from our picture cars. Again, low, wide and close was the formula.

The G-forces in high-speed turns were too much for standard car-mounted remote crane arms, but we had a Porsche Cayenne set up with a vertical column — which they called the ‘elevator rig’ — instead of the arm. That allowed us to zip from an extremely low camera position to about eight feet high in seconds, without dealing with the inertia limits of an arm. Allan Padelford was able to drive this thing so closely to our hero cars that it was scary being along for the ride — imagine our camera crew pulling focus and iris from inside the Cayenne at the same time!

Large Format, Custom Performance

Papamichael: I decided to shoot larger format and to try Arri’s Alexa LF. I liked the falloff quality of the medium-format lenses and the Sphero 65s when I had used them with the Alexa 65 in the past. I was looking for that quality, but I also wanted the characteristics of Panavision’s C Series anamorphics, which I have come to love over the years. I was looking for that Super Panavision 70 feel, and it seemed to me that the LF, which had just come out, could achieve the same large-format look — or close enough, at least!

I asked [ASC associate and Panavision’s senior vice president of optical engineering] Dan Sasaki if he could adapt the B, C and T Series to cover the LF’s larger sensor. He said that he could expand them, and somehow he managed to get them to us a day before our shoot! That meant no testing, but I instantly loved the result. Dan also modified the T Series slightly to take the edge off their usual sharpness, and to match them to the C Series so we could cut smoothly from one lens series to the other. The Bs were pretty much abandoned, since the expansion made them too soft and [prone to flares] for this project.

The close-focus capability of the T Series was especially valuable given the way Mangold embraces being physically close to the actors. With this combination of lenses and sensor, even if you’re in tight, you’re not isolating your actors; you always feel the environment and are able to compose with their surroundings. And you feel the proximity of the other cars, which were all being driven and were precisely choreographed by Robert Nagle, who was cuing the drivers via radio for every beat.

The main unit only had anamorphic lenses. If a spherical zoom was used, it was a 2nd-unit shot for the purposes of mimicking ABC’s Wide World of Sports TV coverage. Everything that the audience sees on the [in-frame] TV screens was generated and treated for the period by us. No archival footage was used.

Colorful Livery

Papamichael: We didn’t do any color filtration — I just embraced the colors that were coming from the period, which production designer François Audouy beautifully reproduced. The cars have such amazing colors to begin with! Our inspiration came from the Super Panavision 70 and Metrocolor look of John Frankenheimer’s Grand Prix — the blue skies are popping, and the contrast and the whites are very distinct. Jim asked if I was okay with all the hard sunlight in the desert scenes. I thought it was terrific and that we had to embrace it. For the Willow Springs racetrack sequence, I was inspired by [ASC member] Caleb Deschanel’s work in The Right Stuff. There’s a scene in that film when Sam Shepard, playing Chuck Yeager, crashes in the desert, and there’s a very brutal quality to the light. When Christian Bale is wearing his goggles and driving the white Cobra, that footage has a similar quality of hard light; [in that scene] Bale reminds me of Peter O’Toole [in Lawrence of Arabia], storming through the desert, ‘taking Aqaba by the North.’ It doesn’t feel artificial or manipulated or ‘digital.’

Partly that’s the result of having contrast that is similar to film stock — not so much latitude, and the blacks are really solid. We used a custom LUT that I built with Lonny Danler. Also, we added film grain to the set LUT so everyone would get used to it!

Fast Work in Pit Lane

Papamichael: We were always moving and adjusting to very different light conditions. For example, for our Le Mans pit-lane set at the Agua Dulce airstrip, we built a 1:1 partial re-creation of an approximately 200-yard pit-area and spectator stands, accurately representing the Le Mans structure of the ’60s. But the set’s orientation was dictated by the existing runway, so it required a lot of maneuvering with our scenes as the day unfolded. In the morning, the sun would rise behind our set, so I would take advantage of the indirect light to shoot dusk and dawn situations, or to create overcast scenes. In the afternoon, the sun would front-light our set, and I would use those hours for sunny scenes, like the start and finish of the race. Luckily, since this is a 24-hour race, I could juggle all the light situations with the assistance of 1st AD Adam Somner. Adam was very supportive of our situation.

Often, the pit action had to intercut and match with the 2nd-unit driving footage coming back from Georgia, which was done in 10 days under ever-changing light conditions. Igor Meglic did his best trying to get all the specific action beats done at the right ‘light time,’ but it was tough!

At Agua Dulce, because of noise restrictions, we could only shoot until 10 p.m. — and since it was late summer, we couldn’t start rolling on our night work until 8 p.m. So each day we’d have this short two-hour window to complete our night work. To accelerate our lighting setups, we placed two [Arri] SkyPanel S360sand two [High End Systems] SolaFrame 3000 movers in a single condor basket. We could use the 360s to create a base ambience, and spot the movers to specifically highlight certain areas; we would pick out a spot, focus in on it, then sharpen or soften the edges of our beam. This was very efficient and fast — we could also control the color with full-range RGB.

Chasing the Perfect Lap

Papamichael: I was really happy with a key scene that takes place after sunset, on a tarmac, with Miles and his son talking philosophically about the allure of racing. We had about a 20-minute window to complete the entire scene, which we shot at a highly restricted area at the Ontario Airport. There could be no grip equipment, because the wind could pick it up, and no film lighting, since it would bother the incoming aircraft.

We hadn’t worked out our exact blocking, but we knew they were going to walk down the tarmac and, at some point, sit. We would also need to cut to the reverse. We mounted an Oculus head onto our dolly, since there was no time to lay any track, and Scott Sakamoto was on Steadicam to cover with a second camera and find an angle as quickly as possible.

It was really a scramble — we didn’t want to come back to complete the scene the next day, since the airport staff was already getting anxious — but in the end it was fun. We made it, and the scene turned out to be one of the visual highlights! The ability to control the skies in the DI also helped make that scene possible.

It would have been hard to shoot this scene on film; it was hard enough with the Alexa LF and the T Series anamorphic lenses in extremely low light. That was true for many of our night-exterior scenes, especially the nighttime rain sequences at Le Mans. But the Alexa LF handles low light levels extremely well. We never rated higher than 1,280 ISO, but I believe you could easily go to 2,000-plus.

Photo Finish

Papamichael: The main challenge in the DI was matching all the shots with varying light conditions. We were trying to maintain this 24-hour timeline during the final race, but blending all the footage between main unit in California and our friends in Georgia was problematic at times. With the help of [senior colorist] Skip Kimball at EFilm, we managed to make it work — I certainly feel the audience will not be conscious of or distracted by our mismatches!

The expansion of the Panavision anamorphic lenses caused significant vignetting, and you feel it in the movie. I normally add a vignette to every shot in the DI, but in this case, the lenses produced this optical vignette, especially on the wider focal lengths. The movie was timed on a white screen and for a white screen, so if you see the film in a theater with a silver screen, it compounds the vignettes — the center becomes too hot. The silver screens are designed for 3D projection and are brighter in the center.

I also apply a layer of film grain in the DI. Skip and I have really tried to perfect our approach to film grain, going back to The Monuments Men [AC Feb. ’14], where I mixed film and digital. Subconsciously you feel it, but sometimes you don’t actually see it. If you take it off, though, you notice that it’s gone — it suddenly looks ‘clinical’ and too smooth. To me, Ford v Ferrari has a filmic quality due to the textures, grain, lenses and, of course, the saturated colors.

We also did a Dolby Cinema pass, which is much brighter and really noticeable on day exteriors: 30 footlamberts, versus 14 footlamberts for the standard DCP projection. The 50-percent grain level that Skip and I settled on had to be reduced to 10 percent [for the Dolby version] because the laser projection was creating artifacts in the highlights.

Beyond the Checkered Flag

Papamichael: The last time we see Ken Miles drive is one of my favorite scenes. We’re in a desert landscape. The engine sound slowly fades as Matt Damon’s voice-over takes over. He speaks on how things change at 7,000 RPM, how you enter a state of weightlessness, how everything fades. Miles’ GT40 is floating through the sun-bathed desert landscape and disappears behind a rise on the road.

We only had one day at the Honda [Proving Center] test track in the Mojave Desert. The sun was setting as we got in our final lap, tracking the car; then we rushed back to another camera setup, on a long lens. We sent the car out again, and we got that last shot where Miles is just driving. It feels very poetic. You sense the connection between these two men and their friendship.

This is of course a race-car movie, with lots of action, but the strength for me is in the characters. That’s Mangold’s forte, working with the actors to define these solid personas, down to every bit part. Matt and Christian have a classic ‘buddy’ chemistry. Shelby has to be a salesman in order to make it all happen, but he also really cares and is a true friend — he risks everything for Miles. To me, it’s a movie about friendship, and being passionate about what you do. It’s an old-school Hollywood film — a dinosaur in today’s studio environment. I hope it finds the audience response to encourage our studio system to make more films like it. I believe there is still a place for these films in today’s world.

TECH SPECS

2.39:1

Digital Capture

Arri Alexa LF, Mini (for 2nd unit and certain hard-mounted car shots)

Panavision C Series (expanded for large format), T Series (modified and expanded for large format), H Series (for 2nd unit, not expanded)

You'll find related coverage on the classic racing film Grand Prix (1966) right here.