Forging Realms for The Rings of Power

Alex Disenhof, ASC conjures post-apocalyptic imagery on a grand scale.

The Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power arrived on Prime Video with a five-season commitment and a reported budget that would make it the most expensive TV series ever produced. Inspired by the appendices of The Lord of the Rings, the show is set in Middle-earth’s Second Age, thousands of years before J.R.R. Tolkien’s main tales, and tasked a trio of cinematographers — Alex Disenhof, ASC (Watchmen); Aaron Morton, NZCS (Black Mirror); and Óscar Faura, AEC (Jurassic World: Fallen Kingdom) — with executing the series’ technically daunting battle scenes, capturing its sweeping vistas and accentuating the artistry of its meticulously crafted sets.

“We basically each had a team making a movie,” says Disenhof, who spoke with AC from London as production had begun ramping up for Season 2. “I had about 80 1st-unit shoot days just for my two episodes. Think of that — a TV show getting 80 days plus 30 2nd-unit days. It was a huge, long production.

Filming by Design

Disenhof, who was invited into ASC membership last year — and who is the focus of this report — shot Episodes 6 and 7, which feature most prominently a cataclysm of flooding and fiery magma, and the forging of an iconic villain’s unearthly domain.

The cinematographer notes that he and director Charlotte Brändström were not guided by the look of the films, or even by earlier episodes, when helping to realize these epic events, but rather by the production’s concept art. This is especially true of Episode 6, “Udûn,” in which a magical blade is used to trigger giant water gushers and a spectacular volcanic explosion that overwhelms villagers — which ultimately creates Sauron’s dark realm of Mordor.

“Charlotte and I wanted to keep in the same world shown in the rest of the show, but we were able to come in with fresh eyes,” Disenhof says. “Our episodes sit a bit alone because we had all this location work, the creation of Mordor and these events that have their own look. We took most of our inspiration from [Ramsey Avery’s] production design. The concept artists created beautiful, painterly images of the sets — it was a nice starting point. Our episodes allowed us to bring a little more grit, because things are getting darker and more challenging for our characters.

“There was some great concept art of the mines of Moria, for instance, that had great single-source lighting in it, reminiscent of Baroque paintings,” the cinematographer continues. “This signaled that the showrunners, producers and our art department all had an appetite for practical lighting and allowing the images to fall off into darkness.”

Disenhof’s work with Brändström marked the first collaboration between the two. “Charlotte is decisive and a great communicator,” the cinematographer says. “We act as a team and she welcomes my ideas. We talk about blocking and what would be best for the story, but also [what’s best] for the light. She understands that part of her job is to make sure it looks great — so she’s a gift to a cinematographer.”

Gearing for Adventure

Season 1 shot in New Zealand from early 2020 to summer 2021, occupying Kumeu and Henderson film studios. Faura shot Episodes 1 and 2, which were followed by an extended production break. This allowed time for the Episode 1 footage to be “edited into a mostly complete episode by the time I had arrived,” says Disenhof, who was able to view this material while he and Morton set about planning their respective installments — with Morton shooting Episodes 3, 4, 5 and 8.

Disenhof and Brändström hit the ground running in early 2021 with such locales as an exterior atop a South Island mountain for a scene in Episode 7 — featuring the Elf warrior Galadriel (Morfydd Clark) and Míriel (Cynthia Addai-Robinson), the wounded queen regent of Númenor — for which they and the crew were flown in by helicopter. The cinematographer notes that the production shot primarily on the Arri Alexa Mini LF in a widescreen 2.39:1 aspect ratio, which “worked out well for our landscapes. For the scene atop the mountain in Episode 7, for example, the widescreen aspect ratio allowed us to craft intimate close-ups of our characters without losing the epic scale of the location behind them.”

The Alexa LF camera also came into play occasionally, when the crew wanted to shoot at a higher frame rate of 48 fps.

The cinematographer used Arri Rental DNA LF prime lenses almost exclusively, having already fallen in love with them while testing them alongside other lenses for the pilot of the Apple TV Plus series The Mosquito Coast. “They offer a great combination of softness and contrast, and possess a dimensionality that rounds out faces and pops them from their surroundings,” he says.

The filmmakers used the mid-range 35mm and 50mm lenses as their workhorses. In the rare instance they needed to go longer than the DNA LF’s longest focal length (135mm), they would grab an Arri Signature Prime lens.

Galloping Through Production

Whenever the show called for more dramatic, slow-motion effects, Disenhof tapped the Phantom Flex4K — which, for example, shot at 500 fps to capture an Episode 6 shot in which Galadriel and the Númenor army ride on horseback across a wide field on their way to help defend the villagers against the Orcs.

The crew used the Angénieux Optimo Ultra 12x zoom on a U-Crane vehicle to track the galloping horses.

When the cavalry joins the melee and the combat escalates, the filmmakers switched to lower-than-normal frame rates for some shots — 22 fps and either a 90- or 45-degree shutter angle for a faster, staccato action style. The idea came from 2nd-unit director Vic Armstrong — the legendary stunt performer who has stood in as Indiana Jones, James Bond and Superman, and who collaborated here with 2nd-unit cinematographer Peter Field. “We worked closely with them, splitting up the attack on the village and some of the horse-charging shots,” Disenhof says. “Vic’s suggestion gives that sequence an extra bit of oomph.” The cinematographer adds that some shots were also sped up in post to amplify the chaos.

To allow multiple episode blocks to be shot simultaneously with the many characters in various locations, the production carried two 1st units — nicknamed “Ent” and “Warg,” after Tolkien creatures — and Disenhof and Brändström bounced between them. They usually designed shots around the A cam and ran up to three cameras, as in the village battle scene. “We would find an alternative or complementary angle with the B camera, and then allow the C camera to roam and find interesting angles or bits of coverage,” the cinematographer says.

Cameras were predominantly on cranes, with each unit carrying a 45' and a 23' Scorpio crane, and a Technodolly. A small amount of Steadicam was employed, and handheld work figured into the battle sequence.

Barnburner

Episode 7 opens on a fiery landscape of destruction where the village once stood. As Galadriel wakes and surveys the carnage, after seemingly being consumed by a pyroclastic cloud, the atmosphere is completely red. Disenhof says that creating the effect was his biggest challenge, and he strove to capture it on set. “We needed to nail it in-camera, because it would have been difficult to achieve that color by pushing it in postproduction without compromising our actors’ skin tones,” he says.

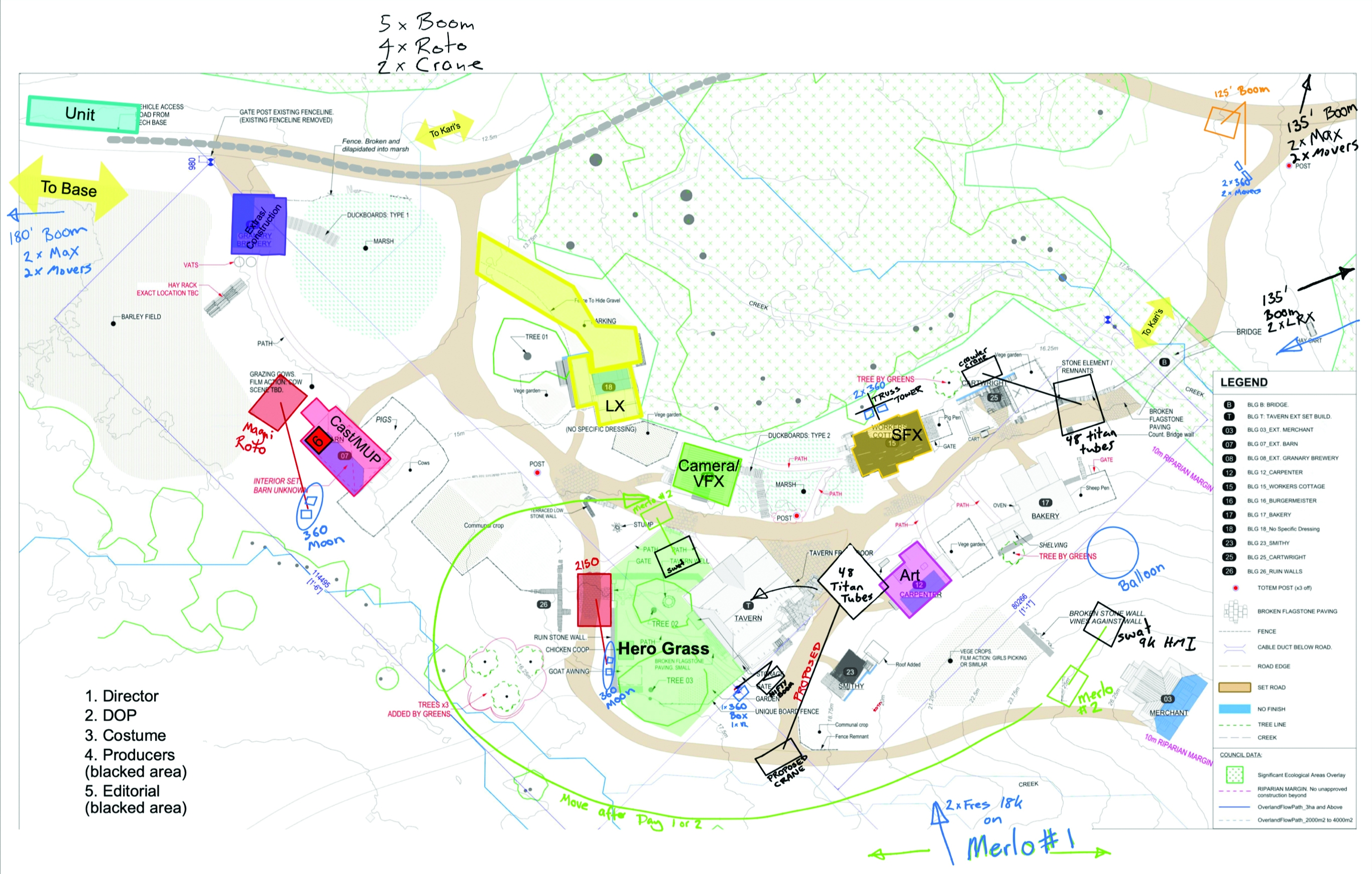

The village was constructed on location, but to better control most of the shots of the post-volcanic aftermath, the production re-created the setting inside a retrofitted horse barn, approximately 70 yards long and 40 yards wide. The crew covered the walls of the barn with bleached muslin and created a giant soft box by rigging Arri SkyPanel LEDs around the set — 72 S60s above pushing through 1/4 Grid Cloth, 45 S360s surrounding the perimeter and eight S360s on Merlo Roto lifts scattered around. They pumped in an enormous amount of atmosphere and had a 5K tungsten Fresnel on an arm shooting through the muslin to create a hazy sun effect through the layers of fog.

Disenhof drew upon real-life references to arrive at the right color. “I used photographs of the 2018 California wildfires as inspiration,” he says. “I also had been in Portland in 2020 during wildfires and had taken my own photography of the skies, which were this kind of burnt orange and yellowy red. I noticed that there are several different tones in that kind of environment. It’s not just a blanket tone.”

To match this look, the crew calibrated the SkyPanels’ color hue to three different settings. “That approach gave us this beautiful gradient from ground to sky,” Disenhof says. “The underexposed parts of the image tended to be more red, and as you got up to the brighter areas, it went from red to orange to yellow — all of which we got in-camera.”

The filmmakers were committing themselves with this strategy, as not much could then be changed in the finishing, which was handled by Company 3’s Skip Kimball. “When you light with that intensity of color, you’re purposefully depriving the sensor of so much information that you can’t manipulate it much more,” Disenhof notes. “If you want to try to turn that image blue, good luck.”

To create a sense of expansiveness within the interior space, Avery and his team created what Disenhof describes as “impressionistic shapes of buildings.” Says the cinematographer, “We interacted with some real builds — [most of which] were two-dimensional wood cutouts painted dark gray or black against the white muslin — but then we wanted to create the sense of depth in-camera using atmosphere and forced perspective.” The visual-effects team added an extra layer of depth with out-of-focus background shapes and provided the falling ash, which the production could not create on the day, due to health and safety concerns.

Great Outdoors

The next challenge was matching the color provided by the SkyPanels in subsequent exterior scenes actually shot outside in natural daylight, such as when Galadriel meets up with surviving village boy Theo (Tyroe Muhafidin) and they traverse a forest and hide from the Orcs. The camera crew found the right combination of lens filters to do the job — Tiffen Tobacco 2 and Tobacco 3 — “so we were able to closely marry the interior-shot and exterior images in camera,” Disenhof says.

Exteriors generally meant trying to maintain consistent lighting through New Zealand’s volatile weather. The crew had 20'x20' flyswatters on hand with either diffusion or black to create shade if necessary, as well as three or four rigs of four Arrimax 18 lights that could extend up 60'-80', which enabled Disenhof to re-create the sun if they lost the light halfway through a scene.

“To combat high winds at night, we created a 30'x30' truss grid covered in Astera Titan tubes hung off a large construction crane,” he adds. “This array allowed the wind to pass through the fixture, whereas a traditional large softbox or balloon lights would have been grounded.

Tunnel Vision

While fire is often a destructive force in the story, it was a good friend to the filmmakers, providing the only other motivating light source other than the sun or moon. Practical lanterns, fire pits and candles figure prominently.

In one plotline, Elrond (Robert Aramayo) — the half-Elf herald of Gilgalad (Benjamin Walker), High King of the Elves — visits his old friend Durin IV (Owain Arthur), a Dwarf prince, in the underground city of Khazad-dûm, hoping the Dwarves will help forge a mighty weapon. A scene in which Elrond and Durin sit across from each other in a tunnel (built onstage), taking a break from mining for the magical metal Mithril, proved tricky to light.

“Movie lights made it feel too ‘lit,’” Disenhof notes. “But lanterns felt real and could be right next to the actors. To get the right exposure, however, the lanterns would be completely blown out. The visual-effects department was able to bring back some texture to the lanterns [via CG 2D textures], which freed me to use them as lighting elements. We snuck in Titan Tubes and LiteMat fixtures, but mostly what you see in that set is what we used.”

The practical lighting team, led by Tony Slack, procured customized ribbon lights from China that Slack dubbed “LumenArty.” New Zealand-based gaffer Sean O’Neill notes that these lights are quite bright “and the color is bang-on at low levels. That was our main source in lanterns and hanging chandeliers. The special-effects team also supplied real flame, including flame bars, fire pits and braziers. We built accessories systems to control any spill.” SkyPanel S360 fixtures created firelight for bigger areas. O’Neill and console programmer Dylan Dwyer pre-programmed flame effects across all fixtures so they always had a file at the ready.

The Size of It

Many scenes involve the interaction of characters of varying sizes. In this case, Elrond is much taller than Durin, although the actors’ actual height differential was not that great. The set was built to make actor Arthur look correct — small — but the dimensions had to be different to make Aramayo seem taller. This required composite work, a modified version of the set, and some bluescreen magic.

In rehearsal, Aramayo sat with a picture of his head sticking up from a backpack and positioned at the greater height the filmmakers wanted. This allowed for the correct framing and eyeline for Arthur, who would ultimately be filmed by himself, looking up toward where Aramayo’s head extension had been. To then create the illusion of a much larger character, for certain moments Aramayo was filmed against a scaled-down version of the tunnel wall, which was placed in front of a bluescreen. “The scaled-down version of the set was only used if Aramayo touched or interacted with it in any way; otherwise, [just] bluescreen was used,” Disenhof says. “This bluescreen was built to match the shape of the existing set, but [also] scaled-down in size” — which kept the actor aware of his spatial restrictions and allowed Disenhof to match lighting with the first set. From there, the separate performances were composited together in post.

“Every shot had to be carefully planned,” Disenhof says. “It looks like a normal scene, but the technology to do that was really complicated. It was satisfying when we put it all together and the audience wouldn’t even think about what went into it.”

Spotlight on Production Design

Ramsey Avery, production designer for The Rings of Power, received specific directives from showrunners J.D. Payne and Patrick McKay.

“They wanted to make sure what we were doing felt real, in terms of building enough scenery so the actors would be in real sets and locations rather than in a lot of greenscreen environments,” Avery recalls. “That was important from the actors’ standpoint, but also from the audience’s — so they would feel there was a real-world here.”

Achieving realistic textures could be challenging, particularly when the art department had to create exterior settings on the stage and natural elements were built by the props department. Avery stresses the importance of camera tests while working in these circumstances. “We did a lot of testing of props, such as how [the magical metal] Mithril looks, how you get it to glimmer, and its visual development,” he says. “We tested several crystalline versus metallic shapes, with varying degrees of translucent materials, and applied several types of iridescent paint. We even tried tiny glass beads and/or glitter mixed in. We explored hitting it with specifically focused light. Eventually, we found a translucent material, shaped with a mix of organic and faceted shapes, then gilded it with real metals and painted it with some gun-bluing iridescence. VFX helped a bit as well in close-ups.

“We also tested leaves — and we tested fabrics in terms of how to get them to read right and how to get the light through the fabrics to read the way we wanted them to,” he continues. “We looked at several types of fabric of varying densities, trying single and double layers. We mixed different colors of greens, yellows and ambers, and even tried some gold lamés. We also worked out how to print the vein patterns and leaf textures, and sandwich dimensional veins between the fabric layers. All of that was looked at in terms of how they played against light — how much light each sample would transmit, and how much they would just glow.”

Introducing light into this tale involved a constant conversation between Avery and the series’ cinematographers. He boiled down this challenge to a simple question: “How do you use sunlight and fire to light everything?”

The crew tested how flame would interact with sets and props, assessing “different types of flame and color temperatures” in the process. They then asked, “How can we adjust the color temperature of [lantern] flame by putting lenses over the top of it, and what types of lenses [should they be]? How do we expose flame, and then how do we hide it so we can use electrics?”

To help tell the story of each culture, they ended up with mostly unique “lenses,” Avery says. “Elves had Venetian seeded glass and capiz shell, both made with real glass or with various cast resins, and subtly colored. Dwarves used mostly open flame, but when the DP needed a more even light, we created resins that looked like crystal or onyx. The Southlanders used oil cloth or horn, which gave a nice warmth to all their scenes. Harfoots kept things light, so, like their dishware, their lanterns were made from paper maché. Orcs used only torches. The Númenóreans had the creativity and craft to use most of that, but we determined that they were the only race who had really mastered glass, so they not only had real window panes, but also heavy glass lanterns, some with very dense color. In terms of open flame, we kept them as much as possible with oil lanterns rather than charcoal or wood.”

Avery worked with the set-decoration department to figure out the best builds for the lanterns, which were tested extensively with cinematographers Óscar Faura, AEC; Aaron Morton, NZCS; and Alex Disenhof, ASC — starting with the concept art.

In more general terms, Avery and each cinematographer “would talk about where the cool light and warm light was coming from and how we balance them,” he says. “For every set, we sat down with the directors of photography and set dec and figured out where the practical lights would go, so they would have the best chance for the lighting they needed. Then, we focused on where we could put our hand lanterns to provide the light to make faces look right.”

— Mark Dillon