From Outer Space, They Live

Director John Carpenter and cinematographer Gary B. Kibbe deliver a two-fisted sci-fi satire on contemporary consumerism and greed.

This article was originally published in AC Sept. 1988. Some images are additional or alternate.

Unit photography by Bruce Birmelin and Sidney Baldwin

John Carpenter makes movies that are out of the ordinary. Leave it to a filmmaker whose subjects have included a haunted car (Christine) and the island of Manhattan as a futuristic prison (Escape From New York) to come up with this one: evil free enterprisers from outer space starring with a former pro wrestler. In his latest film, They Live, Carpenter brings his unusual social commentary to the subjects of subliminal seduction through media, and the growing homeless population.

The story turns the tables on exploitative first-world societies by making Earth a “third world” planet, exploited by aliens who use the mass media to gain control. Posing as successful humans, the aliens corrupt the greedy to their cause, and control the rest through subliminal messages hidden in media. If allowed to continue, the aliens would deplete all natural and human resources, discard the earth like so much trash, and move on to another planet.

John Nada (played by former pro wrestler Roddy Piper) slowly uncovers the insidious plot. He joins the underground movement, which is based in the ever-growing tent city for the homeless, Justiceville.

“They Live began three years ago with a comic book I bought called ‘Nada,’” recalls Carpenter. “It was published by Eclipse Comics, a company which puts out very beautifully rendered science-fiction stories. This particular strip was taken from a short story called ‘Eight O’Clock in the Morning’ by Ray Nelson. In the story, this guy wakes up and realizes that the entire human race has been hypnotized, and that there are creatures among us. I became entranced with the story, but I felt that it should be updated. I thought that it might be more current if the guy woke up and realized that the Reagan Revolution was run by aliens from another planet.”

This eccentric, yet topical premise remained a seed in Carpenters fertile imagination while he made the film Prince of Darkness. But when Carpenter paid a recreational visit to Wrestlemania III, the seed germinated. There he met “Rowdy” Roddy Piper, professional wrestler and future star of They Live. ‘‘My idea of a male hero is based on a person, a very close friend of mine who I knew when I was growing up,’’ explains Carpenter. “Many of the heroes in my movies — Kurt Russell’s character in Escape From New York, Jeff Bridges’ character in Starman — have this person’s qualities in one way or another. When I met Roddy Piper, I felt that he also had these qualities. He looks as if he’s lived life, as opposed to looking like a glamorous Hollywood movie star. He has a rough face, with scars from his fights, but it’s a kind face. I thought it would be a different point of view to use him as the leading character in this story. So finally it coalesced for me. I took the Ray Nelson story, added the political commentary and wove Roddy Piper in as Nada.”

The resulting screenplay incorporates many elements, including science-fiction, action, comedy and political satire. However, Carpenter emphasizes that it is not a horror movie.

Carpenter’s choice for cinematographer was Gary B. Kibbe — who previously shot Prince of Darkness for the director. “I learned the camera when I went to USC film school,’’ Carpenter recalls. ‘‘I shot a lot of film, and spent a lot of time with the AC Manual, so I generally know what’s going on with the lenses and the camera. But there is no way I would consider myself a cameraman. Working with Gary Kibbe as director of photography produces a visual style that I am very happy with. Our working relationship began on Big Trouble in Little China [see AC June 1987]. Gary was the camera operator for Dean Cundey, and I was impressed by two things: his eye and his discipline.

“Unfortunately, in the movie business now, that sort of thing is disappearing. Everyone expects to arrive in town and become an instant star. There’s not a willingness to learn the basics of a craft and put in the years of training that are necessary. Gary is about as far from that as possible. He’s worked behind the camera for years and years, under some of the great cinematographers. His attitude is, ‘Here is the work. How can we make this great?’ His attitude and his basic, innate talent make this a strong working relationship.”

A veteran operator, Kibbe’s lighting style for They Live is a direct outgrowth of the storyline. “John likes a modern-day, realistic look,” he describes. “I pretty much key on low light levels, combining bounce and hard light for emphasis on certain things. Sometimes, I’ll let areas fall off, and then subtly draw attention by hitting something in the background. Working in low levels allows you that subtlety, whereas being deeper, in terms of light balance relationships, tends to make things go black on you faster.

“We shot anamorphic, with Panavision cameras and Ultraspeed lenses. With some of these, we can get down to 1.4. We stayed pretty much between 16 and 20 foot candles for the key, but for some of the larger interior scenes, like the unemployment office and the Biltmore Hotel, that went up to around 25. John shoots all of his pictures in Panavison anamorphic. We almost went to Super 35, but decided to avoid losing another generation. We used Eastman 5294 for night exteriors, and 47 for the day. I tested everything that Eastman had, and I still felt that 47, in terms of richness of color, is what came out best for us. We were shooting in a lot of dingy, grungy places, with textured walls, and for areas like that, I felt that the 47 would give a little more. Also, I’m more familiar with 47 than 97.

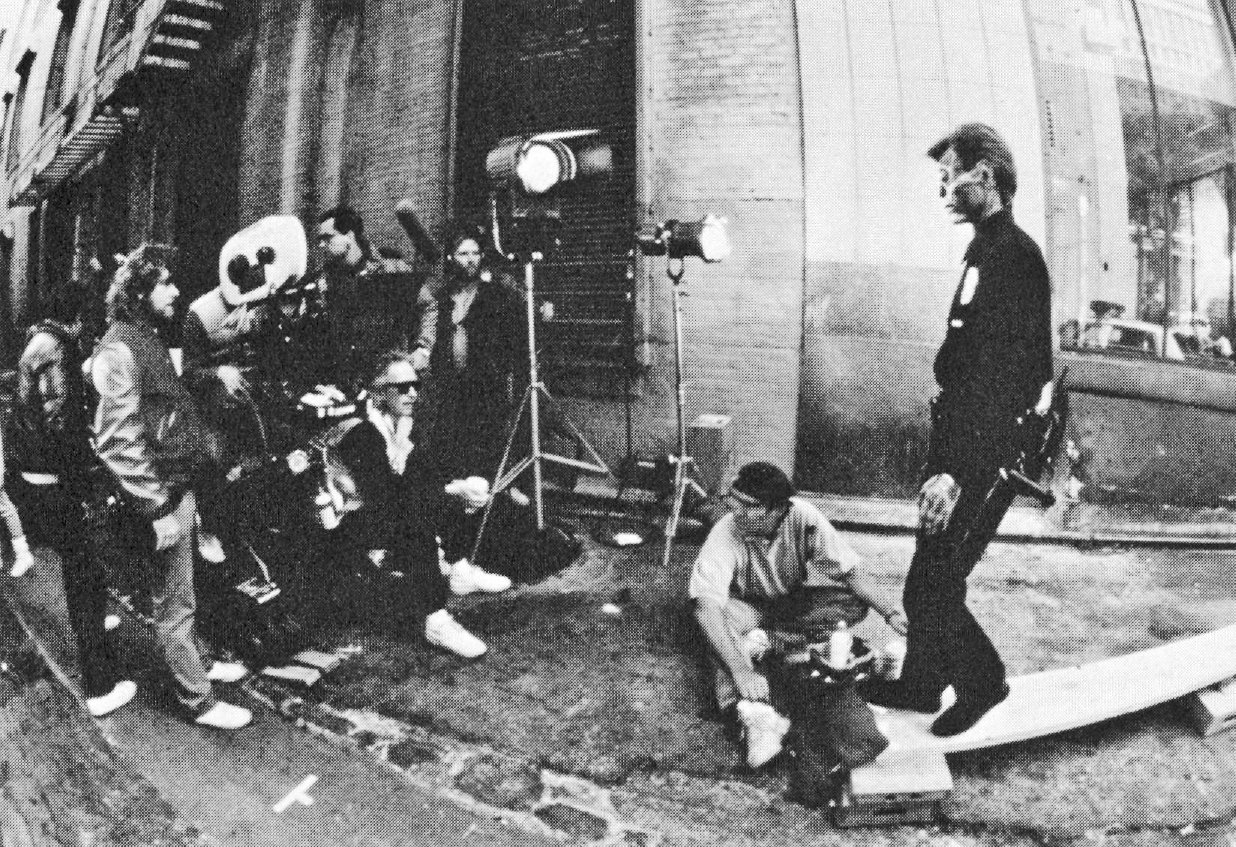

“John and I discussed the use of lenses, and in They Live, as in most of John’s films, zooms are avoided. Prime lenses give you that flexibility of passing by objects, whereas zooms just narrow the field. This way, with a dolly move, you retain the depth and get subjective movement. We had a lot of dolly movement, and quite a few Panaglide shots. The Panaglide is difficult to light for, especially with budget constraints, but it’s so effective when its properly used — when the scene calls for it. On the set, it’s important to be able to respond to anything that comes up — and John likes to be spontaneous.”

“Spontaneity is very important to me,” agrees Carpenter, “so much so that I don’t even storyboard my movies anymore. I used to storyboard, probably because I came out of film school, and I thought it would be cool — you know, Hitchcock did it, so I’ll do it. And I think the result is often a movie that looks like a computer card. Producing a visual image should be instinctual. You see a lot of films that feel punched-out and cold, and you can see the storyboards going by. The other problem I have with storyboarding is that it makes movies even more like television commercials and MTV. They’re beautifully shot, just gorgeous and mounted with such slickness, but without any feeling of humanity — just an anonymous veneer.”

Carpenter has strong feelings about what he considers to be the inhuman nature of today’s films: “I find that the biggest movies now, which are making the most money, seem to be anonymous. They’re not made by a person — there’s nobody there to provide vision. The studios test films in terms of demographics, which results in films that are familiar to everyone and offensive to no one. There’s a hypnotic/symbiotic relationship — we give the public what they want, and they sleep through it. So with films like They Live, we’re trying to break free of that.”

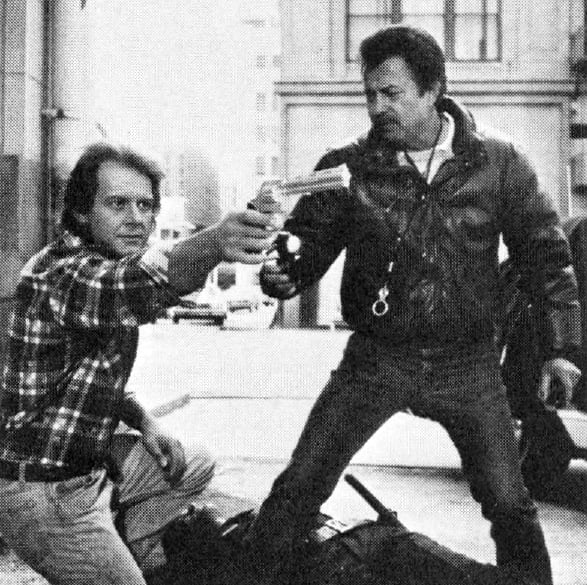

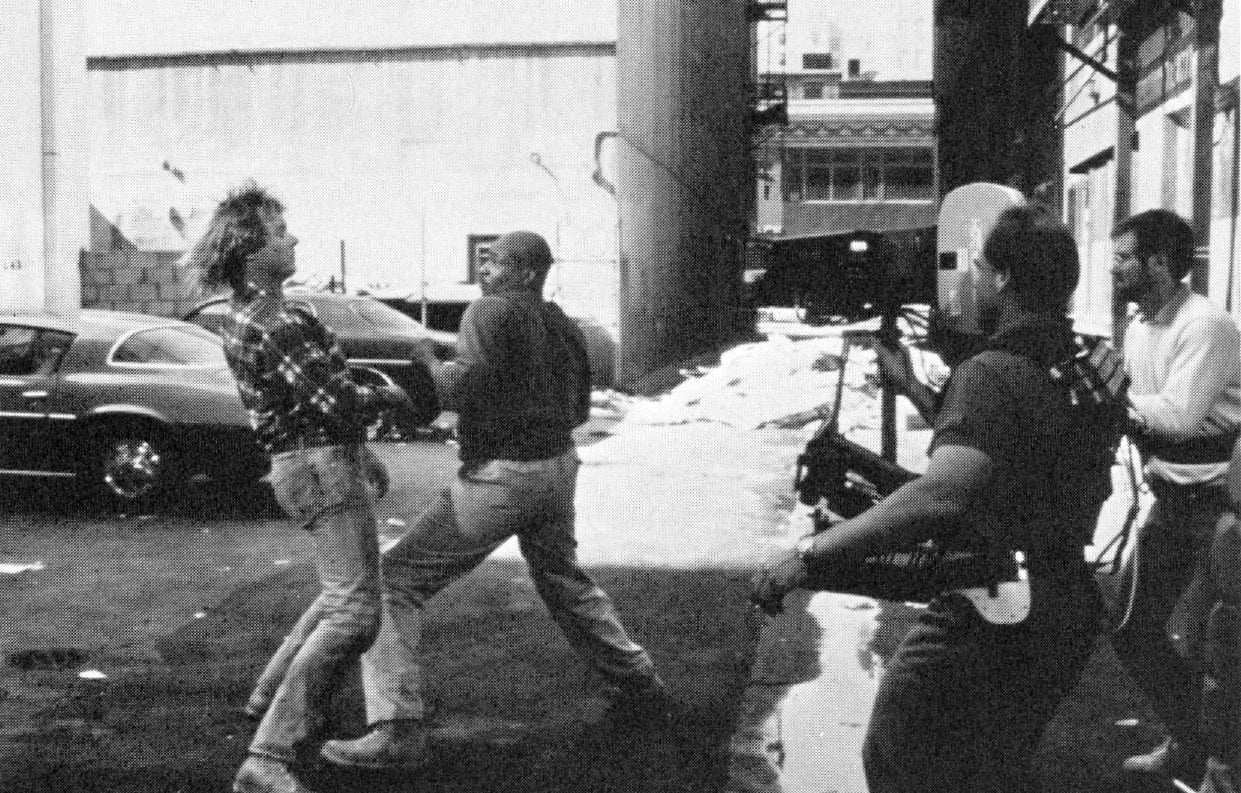

Roddy Piper’s wrestling experience came in handy for an extended fight scene. Nada tries to convince his friend Frank (played by Keith David) to try on the sunglasses (the sunglasses being an important story point). A disagreement of this nature would not normally kick off a knock-down, dragout battle, but in Carpenter’s hands, it becomes a symbolic, epic struggle between the true-blue fighter of the good fight, and he who would sell out his friend.

“The fight becomes a battle of wills between the two men,’’ says Carpenter. “It reminds me of the ending of The Quiet Man, where John Wayne is fighting Victor McLaglen. They’re fighting over something relatively insignificant, but there are broad thematic undercurrents. We shot the scene in an alley over a period of four days. By using the Panaglide and some of the power moves that Roddy knows from wrestling, we tried to break from the stereotypical action formulas. We rehearsed the fight for weeks, and every move was scripted. There is real contact, and they’re beating the hell out of each other, but the fight has some ballet-like qualities. I haven’t seen anything like it in recent film.”

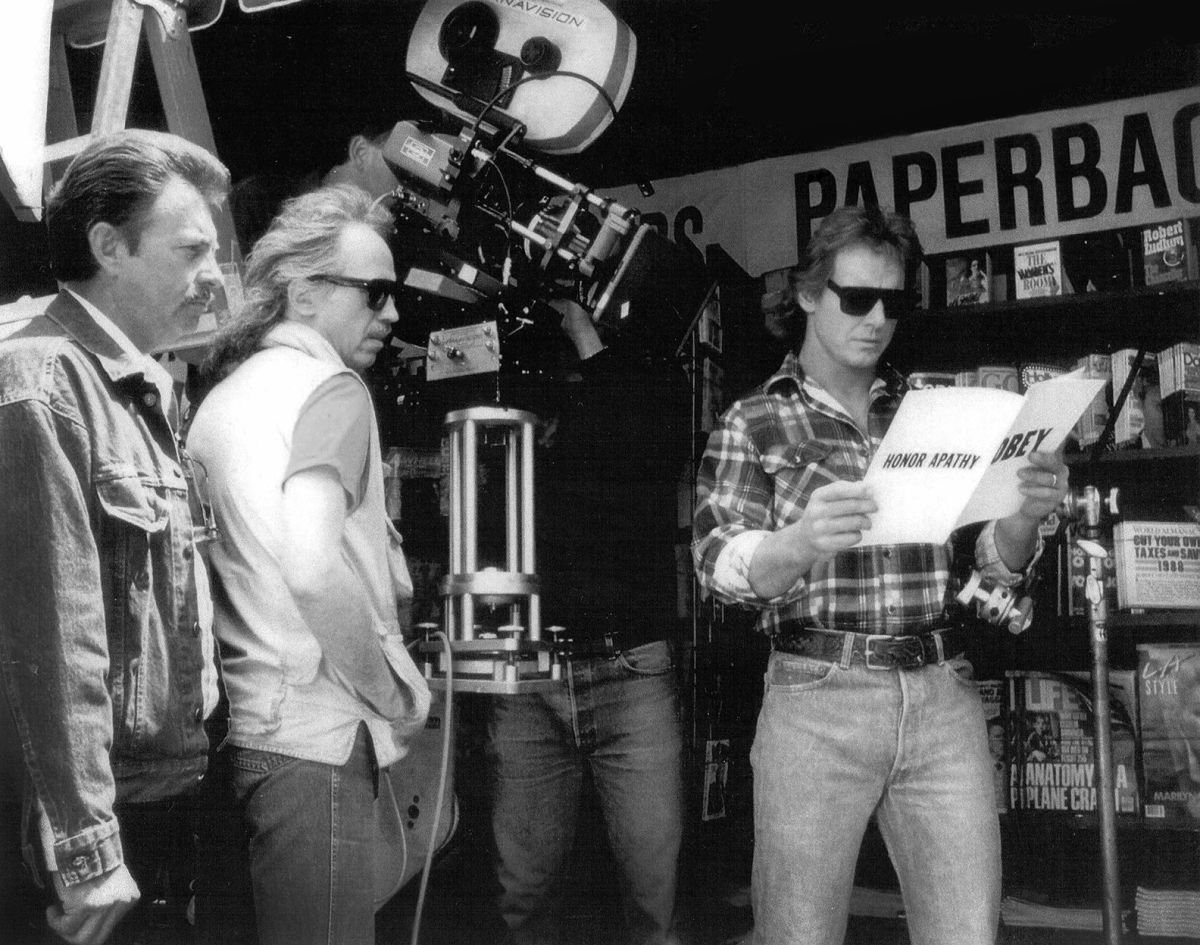

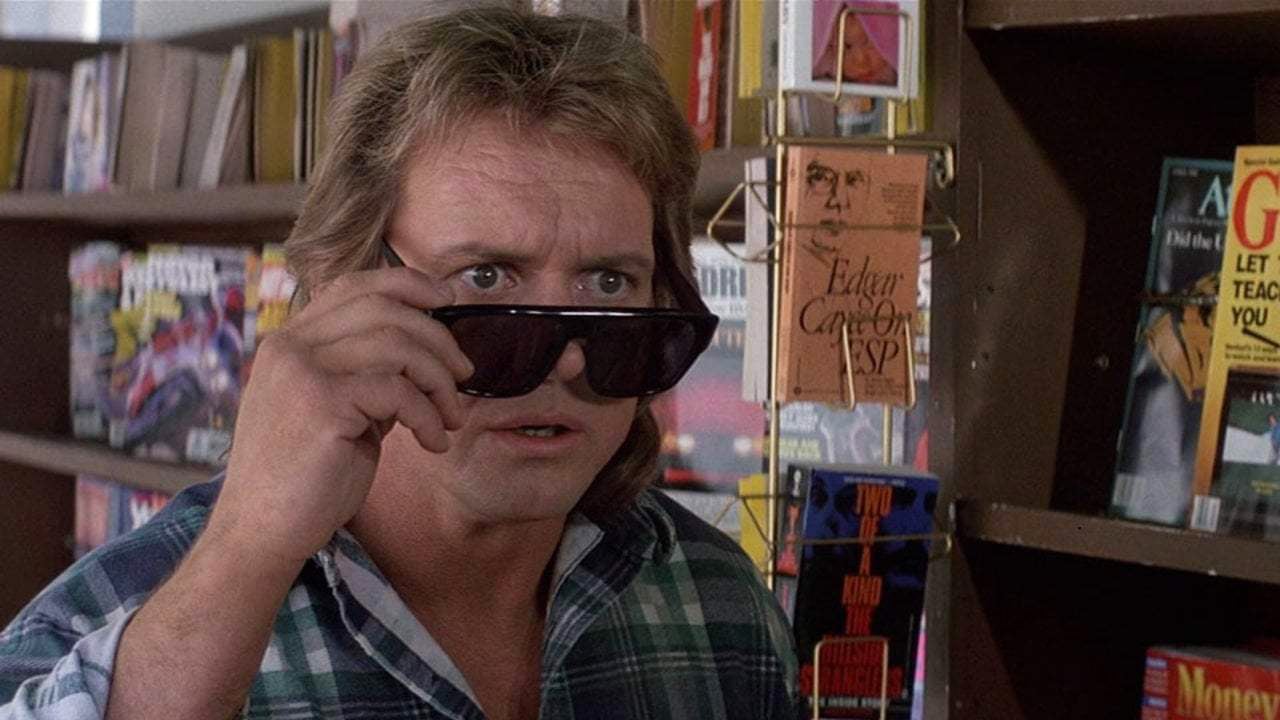

In a turn of the story — reminiscent of William Castle’s 13 Ghosts (1960) — Nada finds that by wearing special sunglasses, one can differentiate the aliens from actual humans. The glasses also reveal omnipresent subliminal messages meant to guide earthlings into conformist, economically efficient lifestyles. Signs that appear normal to the naked eye are revealed to have suggestive inscriptions.

Unfortunately, the glasses cause excruciating headaches for the wearer. After considering a number of alternatives, Kibbe and Carpenter decided to use black-and-white for POV shots through the glasses, with electronic interference to give the impression of pain. Here, the cinematography takes an active role, drawing the audience into the story by revealing another level of perception, depicting visually what Nada feels as well as sees.

Veteran effects specialist Jim Danforth did the photographic effects for the show. He discusses his techniques for the black-and-white sequences, and the other effects shots for They Live: ‘‘In the film, there are some matte paintings — Bill Taylor, ASC of Illusion Arts helped with the matte work — some optical effects, and a couple of stop-motion animation shots, about 10 special effects shots in all. The interesting aspect is that the picture is in ’Scope, which severely complicates the visual effects problems. In order to overcome that, I resorted to the interlace process technique, which I don’t think has been used in a number of years. I built a special front for the Mitchell camera, which enables me to rack the lens across, so that I can shoot a left half and a right half. In other words, I divided the ‘Scope frame down the center, and shot a non-squeezed left-hand image and a non-squeezed right-hand image. You can’t do that by panning the camera, because you get a keystoning effect, and a cosine distortion effect. The lens is slid across like a rising front lens on a studio view camera.

“We shot several background plates in that fashion, which are rear projected with a double projector, one projector for each image. They’re fused together with a system of adjustable masks, really just cutters, in the light beams of the projectors,” he explains. “This way, we get a very wide image, a greater information recording area than regular anamorphic 35mm or VistaVision, so that keeps the quality up. This image is rephotographed with an anamorphic lens on the process camera — which is photographing the matte paintings and the projected backgrounds. The same goes for the animation sequences and their projected backgrounds.

“The straight opticals are done on a printer, using material that is already squeezed,” Danforth continues. ‘‘There was one scene in which we had a kinescope effect, where we had to take a film scene and turn it into a video image. The film was not shot squeezed, so we had to transfer that to tape, play the tape onto a video monitor and shoot it with the squeeze lens on the taking camera. To avoid the sync problems and frame interlock equipment, I just shot it stop motion. The scene was done the usual way on the optical printer.

“The black-and-white scenes for the film were shot on color stock. Originally, I was going to ‘de-colorize’, if that’s the right term, the scenes, which they wanted very contrasty. We made a number of tests on the optical printer. In order for us to get a range of contrasts, I made two prints from the color negative: a 5234 black-and-white print, which we developed to a gamma of . 65, and a 5369 black-and-white print from the color negative, which went through the normal gamma, about 3.2. These were printed back onto internegative stock. I determined the right filter pack for neutralizing, so that when printed on a normal light at the lab, it gives you a true black-and-white — a totally neutral image. By splitting the exposure between one pass from the low-contrast 5234 and one pass from the high-contrast 5369, we were able to get a range of contrasts. If we went 50/50, we’d get something in the middle, if we go entirely from the 34, we get a very low contrast, a very 1930s black-and-white look. Unfortunately, all of this work eventually became somewhat academic, because they subsequently decided to do the decolorizing electronically, in order to add the interference effect. For some of the scenes, I was also able to neutralize some of the process projection, so that I was projecting black-and-white plates and photographing the black-and-white background, while adding a painted black-and-white foreground which was photographed on color stock. It worked out pretty well, and I was able to get a neutral, true, black-and-white image.

‘‘Another challenge was a scene which had to go from color to black-and-white in one scene, on one piece of negative,” recalls Danforth. “There was a matte painting of a color scene, a building which was made to look like an ad was painted directly on the plaster work. I did a wipe in the camera from the color background with the color painting to a black-and-white background with the black-and-white painting. The black-and-white painting is different from the color painting; it has the secret message that the characters see when they put on the glasses — the subliminal image. That shot was done onto color stock in the camera. But it was neutralized so that the color image is normal and the black and white wiped on. We went to great pains to try and keep the non-dupe quality level up, but that may be processed electronically, too, so I’m not sure how it will look.”

Danforth applied his animation expertise to two scenes involving an alien operated flying spy camera, which tails and photographs unsuspecting humans. “The spy camera is a flying saucerlike vehicle, about 2’ in diameter, and it looks like a yo-yo flying in its side,” he says. “It’s a dimensional model with gear mechanisms inside of it for the expansion and contraction. When it finds its subject, it pauses, hovers in the air, and expands and opens up. Then a snorkel-like hose with a camera on the end comes out, looks around and takes pictures. After building the model, I shot these two scenes with a normal stop-motion animation technique.”

They Live is the story of a battle against aliens who came to take over the earth, using human greed as their ally. At the same time, it is a social commentary with striking parallels in today’s society. John Carpenter’s commitment to making out of the ordinary films is tempered, however. “I must tell you that my criticisms of society and the film business are not entirely serious,” he says. “I’ve made a lot of money in the film business the way it is run today, and I am a complete capitalist. I’m just advocating a little humanity in the world. In order to do that, you have to go strong in the other direction; be a little outrageous. It’s fun to attack the status quo.”

Kibbe went on to shoot another five features for Carpenter: In the Mouth of Madness, Village of the Damned, Escape From L.A., Vampires and Ghosts of Mars, as well as the TV series Body Bags. The cinematographer was invited to join the ASC in 1996.

AC also discussed the making of Carpenter’s horror classic The Thing with director of photography Dean Cundey, ASC.