German Cinema Comes to Hollywood: AC in the 1930s

Excerpts from the AC archives mark the arrival of a bold new style during the 1920s and ’30s.

Excerpts from the American Cinematographer archives mark the arrival of a bold new style during the 1920s and ’30s.

By Luci Marzola

In the 1920s, Hollywood cinema dominated screens throughout the world, but one country’s industry came to rival it: Germany’s. The country’s defeat in World War I led to economic hardship and massive inflation, and, at the same time, a blossoming of the arts that was hugely influential on the rest of the world. This Weimar culture lasted until the Nazis came to power in the early 1930s, which led to a mass exodus of talent to Paris, London, New York and Los Angeles. German Expressionist masters such as Fritz Lang and Karl Freund (who was later invited into ASC membership) came to Hollywood and helped define film noir — but the German influence on Hollywood began much earlier than this, and American Cinematographer was covering the trend from its inception.

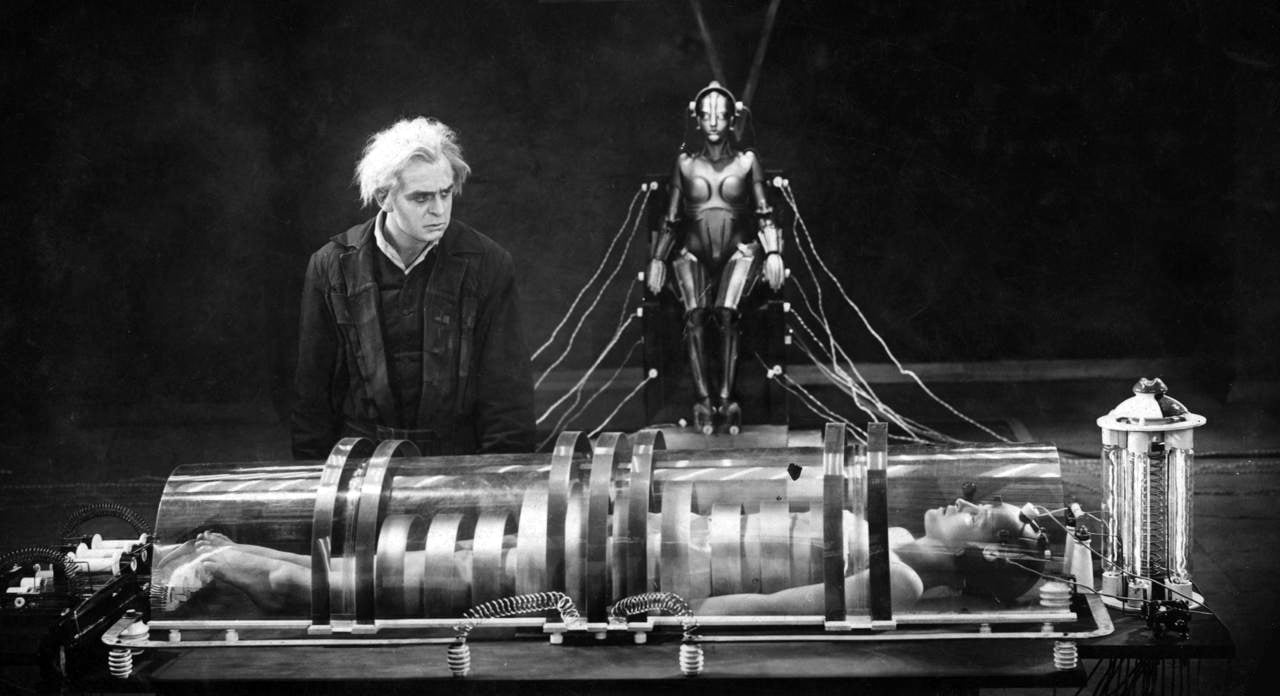

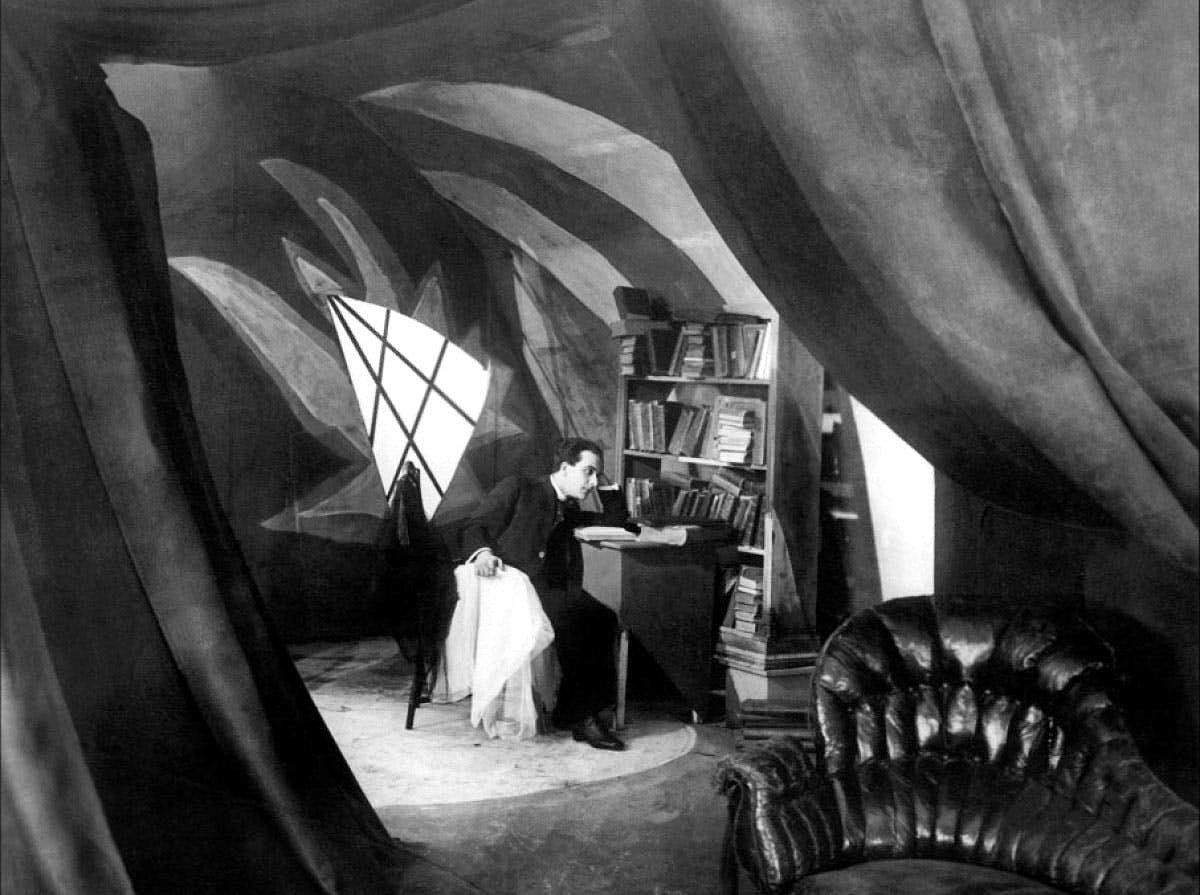

German Expressionism is often used as shorthand for Weimar German cinema, though only a dozen or so of the many hundreds of films made during the period can really be labeled as Expressionist. The name came from an art movement that began before the war and gained mainstream popularity during the postwar period. Expressionism’s emphasis on aesthetic exaggeration and the externalization of the psyche moved into several art forms, including theater and graphic art. Though films that could definitely be categorized as Expressionist were small in number, many of them made the biggest impact and have stood the test of time, including The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920, directed by Robert Wiene and shot by Willy Hameister) and Faust (1926, directed by F.W. Murnau and shot by Carl Hoffmann).

In the pages of American Cinematographer, the attitude toward the breathless coverage of these unique films was often skeptical. In May 1921, the satirical “Jimmy the Assistant” column ran with the title “The German Invasion” and looked upon the recent success of Madame DuBarry (1919, released as Passion in the U.S.) and Caligari as a threat to American jobs. In 1922, Jimmy the Assistant likewise went after The Golem (1920, directed by Paul Wegener and Henrik Galeen, with cinematography by Karl Freund), conceding its artistic greatness but passing judgment for the Expressionist film’s use of exaggeration in its sets and tinting.

The earliest years of the magazine are full of short jabs at the popularity of German films, which threatened both the dominance of Hollywood films and the Hollywood style. However, the attitude American cinematographers held toward the German influx began to change when Weimar filmmakers started moving into Hollywood’s studios.

Ernst Lubitsch was the first to arrive, though his films were not in the Expressionist style. Instead, he had made his name with historical epics such as Madame DuBarry before shifting into the sophisticated comedies for which he is now remembered. In a 1923 AC article, Lubitsch explained why he didn’t bring his German crew with him to Hollywood, extolling the superiority of American cinematographers. Lubitsch asserted that everyone in Berlin knew that Hollywood cinematographers were “in a class by themselves.”

By the mid-1920s, the growing importance of the German film industry could not be ignored in Hollywood. Freund’s spectacular photography on films such as The Last Laugh (1924, directed by Murnau) and Variety (1925, directed by E.A. Dupont) was the talk of the trades. While the earliest Expressionist films had relied more heavily on stylized sets, costumes, and film tinting, these films were undeniably masterworks of the camera. As AC editor Foster Goss put it in October 1926, “Whatever may be the excellencies or the crudities of the German-made motion pictures, they at least are centering attention on one long-neglected fact — that the cinema is an art distinct and complete in itself.”

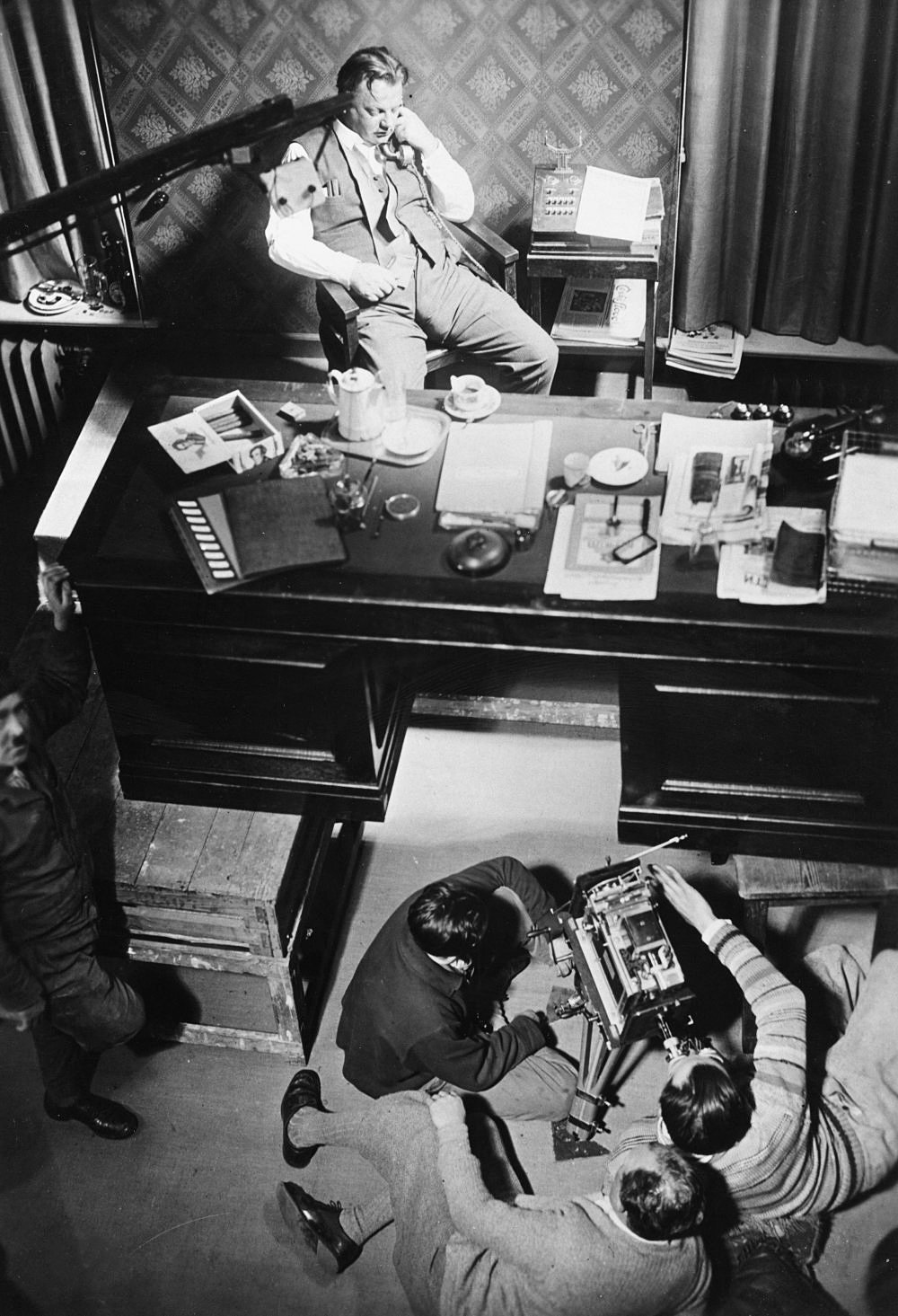

The Last Laugh, which is considered the most important of the Kammerspielfilm chamber dramas, saw Freund and director F. W. Murnau popularize the “unchained camera.” At the time, camera movement had gone out of fashion, in favor of elaborate lighting and carefully chosen angles. Freund’s roving camera, which opens the film by descending in an elevator and gliding across a hotel lobby, was perhaps the single most talked-about camera technique in the history of motion pictures to that point.

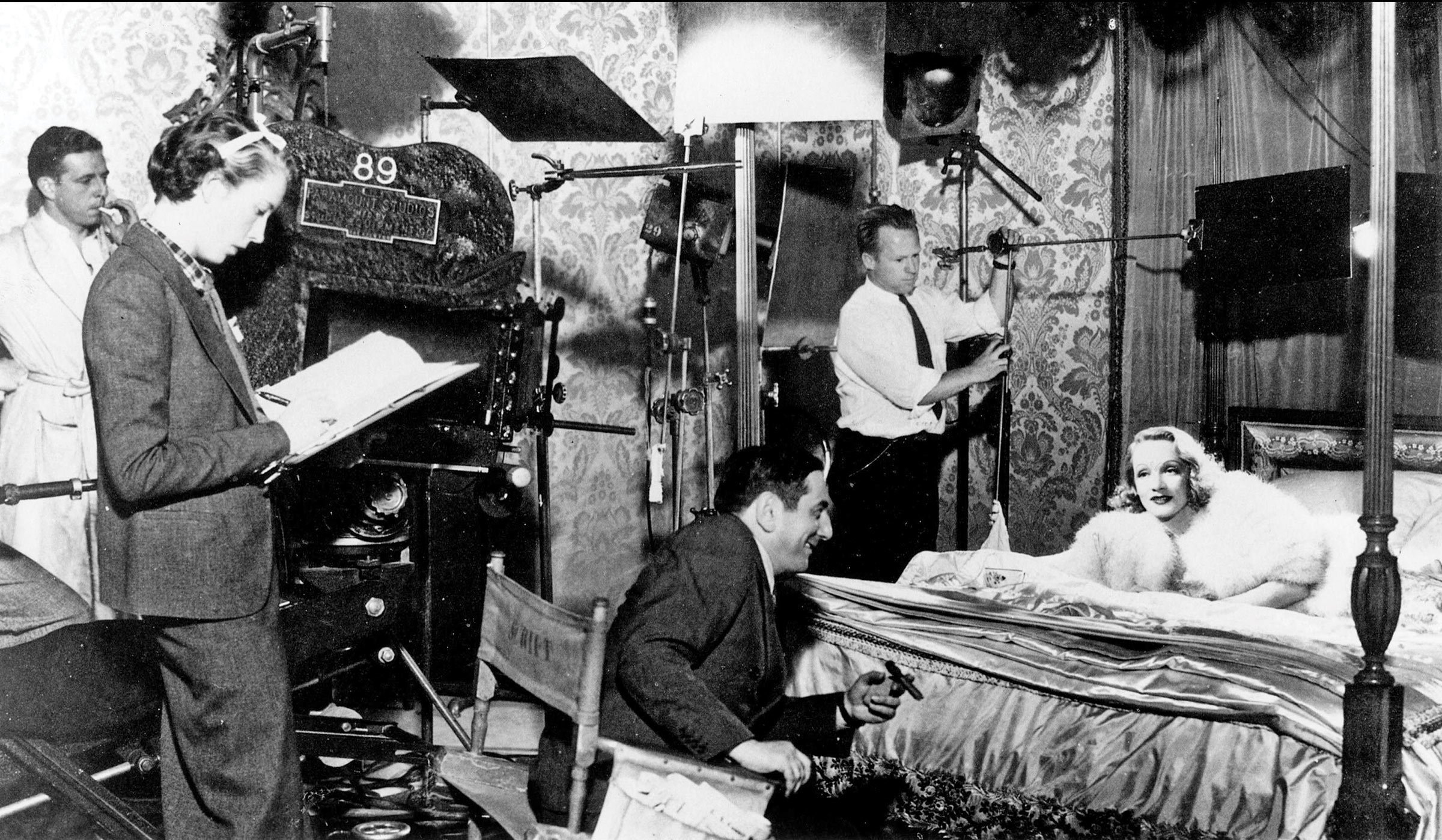

While many in Hollywood scoffed at the showiness of cameras positioned on cranes, spinning plates, and zip lines, the unchained camera suddenly became a staple of nearly every major Hollywood film of the late 1920s — especially when Murnau decamped to Fox to make his masterpiece Sunrise (1927). While Murnau brought writer Carl Mayer and set designer Rochus Gliese with him from Germany, Freund stayed behind. Murnau instead employed ASC cinematographers Charles Rosher and Karl Struss, who adopted many of the flourishes of the German style while melding them with Hollywood glamour.

Rosher, at the time known as Mary Pickford’s cinematographer, actually met Murnau in Germany while making a film at UFA, the country’s biggest production company. Rosher saw working with the German crews as a mutually beneficial exchange, telling AC he “expects to learn as much from the methods there as his fellow workers may gather from American production methods, as practiced by himself while he is in Germany.” The trail of influence between Berlin and Hollywood went both ways, and American Cinematographer was quick to point this out.

By then, the German film industry had been infused with Hollywood money. When inflation was stabilized in 1924, the cost of production rose and it became affordable to import American films. The rising costs, and particularly the massive overruns on Murnau’s Faust and Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927) led to UFA going bankrupt. MGM and Paramount subsequently gave UFA loans in exchange for guaranteed placement of their films in UFA’s theaters. This led American films to gain favor in German cinemas, as they already had throughout the rest of Europe and in most of the world.

Despite the general acceptance of German directors and techniques in Hollywood, the ASC continued to advocate for the use of its own members over bringing German cinematographers to Hollywood. In June 1928, American Cinematographer reprinted a lengthy article from Motion Picture Classic arguing “They are Better in U.S.A.” The author explains that while the studios could not get enough of importing directors and stars from all over Europe — from Emil Jannings to Greta Garbo to Alexander Korda to Victor Sjöström — they were not bringing over cinematographers because “Our own... are good enough.” Freund and Hoffmann are mentioned as being exceptional among foreign cinematographers, while the average Hollywood cinematographer is described as being equally adept.

Yet even as the January 1927 release of Metropolis (viewed as the last true Expressionist film) heralded the end of the boom time, the German industry continued to produce important films into the early 1930s. Sound came to Germany about a year after the U.S., and despite the fact that many key filmmakers had already left the country, this technical breakthrough led to a last creative burst in German cinema before the Nazi regime took control.

Both new and veteran directors found creative uses of sound, while maintaining the flexibility of the moving camera and complex editing that had defined German cinema toward the end of the 1920s. Fritz Lang’s first sound film, M (1931, shot by Fritz Arno Wagner), is a shining example. In April 1930, American Cinematographer ran a detailed account of the inner workings of the German studios, from the lights used to the laboratory processes, concluding that the primary difference from Hollywood was the skill the German crews demonstrated in working with less money and equipment.

Hollywood’s interest in German films faded as the prospect of American audiences watching foreign-language talkies fizzled (though there was always interest in German-made filmmaking tools). The slowdown in production that came with sound was accompanied by Germany’s changing political climate. The situation led many filmmakers working in the industry to head to Hollywood even without big contracts, including Freund and Fred Zinnemann, both of whom left Germany in 1929.

By April 1933, as Hitler and propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels strove to remake the German film industry to reflect Nazi ideology, Jews were forbidden to work on German productions. Those who hadn’t already fled the country left, including Billy Wilder and Robert Siodmak, along with many sympathetic non-Jews. Goebbels offered Lang a high position in the Nazi film industry, but Lang refused and relocated to Hollywood.

It’s notable that the word “Expressionism” is difficult to find in the pages of American Cinematographer, but the impact of the German film industry on Hollywood is much broader than one artistic movement. To reduce the impact of these filmmakers to the concepts of roving cameras and Expressionist lighting is to miss the larger impact of Weimar German filmmakers on Hollywood and world cinema. For example, once Freund came to America, he not only shot noir classics such as Key Largo (1948), but also developed the dominant sitcom shooting style — deploying three cameras and flat lighting — on the iconic television series I Love Lucy (1951-’56).

Throughout its history, one of the great characteristics of the American industry has been its ability to adopt and absorb the filmmaking techniques — and filmmakers — that make waves around the world. There is perhaps no greater example of this than the German influence of the 1920s and ’30s. The work of Weimar German filmmakers in Hollywood (as well as in Paris and London) is so central to the development of world cinema that it’s impossible to imagine the history of the movies without it.

![]()