Going Extreme With Divinity

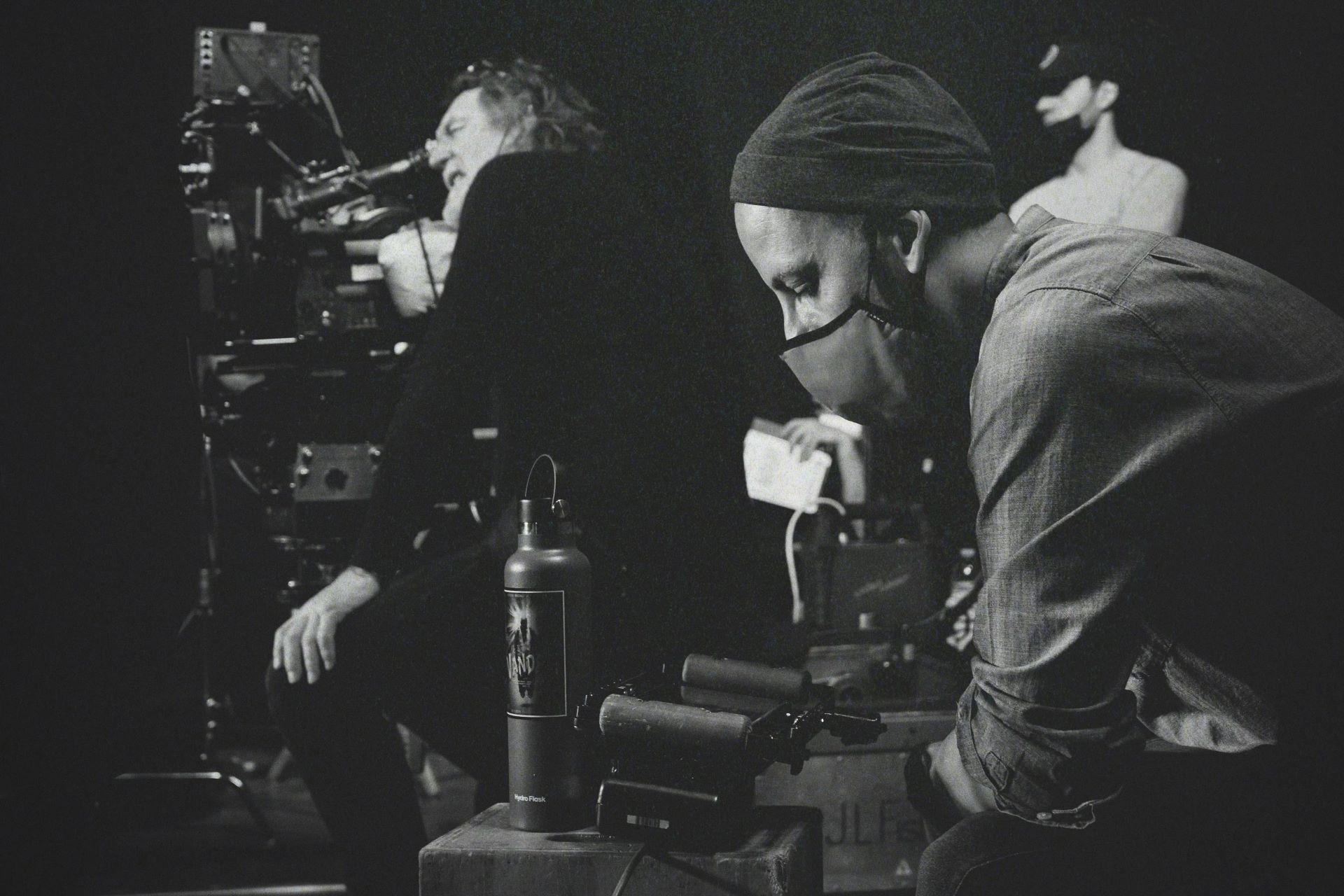

Cinematographer Danny Hiele creates high-contrast images for Eddie Alcazar’s lo-fi thriller

Described by some as "the best kept secret in cinematography," Danny Hiele's name might not be on the tip of your tongue, but you've definitely seen his work. With 40 years in the industry, his CV includes award-winning commercials, as well as music videos for such artists as Audioslave, Frank Ocean, Kendrick Lamar, P!Nk, and Rihanna, among others.

In the realm of cinema, his most frequent collaborator is director Eddie Alcazar, for whom he photographed the short films Fuckkkyouuu and The Vandal, and, most recently, the feature film Divinity, which premiered in the 2023 Sundance Film Festival's NEXT section and was released to cinemas in October 2023.

In Divinity, scientist Sterling Pierce (Scott Bakula, in video flashbacks) creates a secret immortality-granting serum. After Pierce's death, his son Jaxxon (Stephen Dorff) commodifies the serum, which results in a drop in natural births and the total perversion of society. Two mysterious brothers (Moises Arias and Jason Genao) concoct a plan to abduct the entrepreneur, and with the help of a seductive woman named Nikita (Karrueche Tran), are set on a path hurtling toward true immortality.

“Eddie and I both have an affinity for pushing creative boundaries. Staying in the middle of the road makes you roadkill.”

American Cinematographer: How would you describe your basic approach to shooting Divinity?

Danny Hiele: We had to consider the unique challenges posed by the natural environment, which included rocky and desert landscapes that were difficult to access. I aimed to create a lighting design that required minimal adjustment during shooting, thereby creating a more relaxed atmosphere for the actors. Additionally, I had the support of an excellent focus puller, John Sekula, who did not rely on marking positions, giving the actors greater freedom of movement. I prefer shooting handheld, especially in close-ups, to capture facial nuances while still incorporating the surrounding environment. To maintain a coherent visual language, I often opt to work with a single lens throughout the shoot.

Do you operate yourself?

Yes, I'm like a doctor who also operates. [laughs]

And this was shot on Kodak 16mm reversal film.

Yes, it's a very tricky film stock — either it's black or it's white. There's a little bit of variation in between, and we love that. For instance, in the movie, you'll notice the actor is hardly visible at times, in silhouette, but then one step forward and he hits the light. The narrow latitude of reversal film creates this tension.

How does working in this way best tell the story?

It's a mystery. You have these two brothers, and their story unfolds step-by-step, so it's vital for the viewer to be in sync with the story. It's also important to me that we feel the environment as well as the actors' emotions. Take the scene where Stephen is tied to a chair in his home; you still feel the whole outer landscape behind him.

The imagery in this film is highly expressionistic, reminiscent of Alphaville, THX-1138, and Metropolis. Did you have these films, or similar ones, in mind during production?

No, I mostly go with my intuition and the story. I appreciate films like Orson Welles's Touch of Evil or the black-and-white works of Tarkovsky, but I don't specifically work with references. It's more about evolving choices on the spot and aligning with the director's vision.

Like going dark.

Yes, or going extreme. It all depends on the project. Some of my best work has been like that. For example, I have two commercials in the permanent collection at MoMA. One is for Visa, recognized in 2001, and the other is for Beats, "The Game Before the Game," which won the AICP Award. With commercials, you're working with stars and you might get 10 minutes to get all of your shots, or maybe 45 minutes if you're lucky. You have to be extremely accurate and know what you want. With Eddie's film, it's the same. Since it's an independent, no-budget film, things have to move quickly. It's like surfing, you have to catch the wave.

I noticed some additional photography credits for Matthias Koenigswieser, Marc Bertel, and Moritz Uthe. Were they responsible for filming sequences you weren't available for?

There were maybe five instances where I couldn't be there for a day's shoot. Naturally, I'd have loved to be there every day, but due to the project's nature, Eddie might decide in the middle of editing that he wants an extra close-up or something. We've done many pickups like that. Sometimes we would get 40 shots in a day. It's really fast-paced; you don't hesitate, you just go for it.

There's a credit for a storyboard artist, Jason Shaw Alexander, and the film has a kind of stylistic specificity, but you seem to be suggesting that you didn't work with storyboards all that much.

We did have storyboards, but they serve more as a general reference rather than a shot-for-shot blueprint. When the actors are on set and run through a scene, that's when things really take shape. The storyboard informs us of basic needs like close-ups or wide shots. In essence, it's like free jazz: we have a team and a general theme, and we improvise within that framework without going off on a tangent.

Can you speak to the film's collage-like quality, with its blend of live-action film and video and stop-motion animation?

We shot some scenes on VHS, and others on Super 8. The majority — about 90 percent — is 16mm. Misha Klein's animation techniques, like in the fight scene, are consistent with the ones we used on The Vandal. Eddie enjoys mixing these formats; it's part of his artistic language.

Did you know in advance what would be animated or what would be shot on set versus on location?

For the animated portions, yes, we had that planned. But for the live-action scenes, it was more fluid. Eddie might decide to move from a house to a museum, and I'd adapt the lighting accordingly. Despite not being present for the animated parts due to other commitments, my team knew how I'd light those scenes.

Was your approach to the fight sequence more structured, given that it had to be integrated with stop-motion footage?

In those cases, precision was key. We had a checklist of shots we needed — inserts, close-ups, and so forth. The challenge was recreating the same lighting conditions for the stop-motion and live-action segments to ensure a seamless blend. The stop-motion was mostly completed before the live-action inserts, so I had a glimpse of what was already in progress in that department, and I adapted my live-action shots accordingly. Eddie keeps some cards close to his chest, so it's possible he was still tweaking the stop-motion even then.

How were your choices in lighting and framing influenced by the various environments?

When I go on location scouts with Eddie, we walk through different spaces and rooms, and we often do this in conjunction with the production designer Paul Rice. When it comes to composition, for example, I might suggest a wide-angle shot for a particular scene. We had the freedom to arrange the set elements according to our vision, so if we want to emphasize a certain statue in the frame, for instance, can make adjustments on the spot. My approach is to keep the setup fairly lightweight and not to alter things excessively once they are in place so we have the flexibility to shoot almost 360 degrees around the room. Of course, having a talented production designer significantly enhances this improvisational style.

Some key scenes take place outside at night in the desert, and these are particularly striking — especially the way the sky is captured.

Some of the nighttime desert exteriors were digitally enhanced during the grading process, but I shot these scenes using the day's last light, often with a red filter to intensify the color. It's not a day-for-night technique where you shoot in bright daylight and then stop it down in post. Instead, I shot when the sun had already set, capturing the dimming natural light. The aperture was wide open, and you simply have to cross your fingers and hope for the best.

So you're shooting just past magic hour.

Yes, the scenes with the brothers walking in the desert are shot during that brief period; you have about half an hour to work with, and then you return the next day to pick up whatever you couldn't complete during that initial half-hour.

Did you push the film for these scenes?

I was actually pulling it, sometimes just half a stop, depending on how close I am to the edge of exposure. Pulling the film gives the image a sort of velvety texture and also slightly reduces the grain.

Which lens were you primarily using?

I used a Panavision Primo lens on an Arriflex SR-3 camera. I had three lenses in total: a 14.5mm, a 21mm, and a 35mm. All were Primo close-focus lenses. I've been working with Panavision Hollywood for many years, so they're always willing to assist me.

Did you have a preferred focal length?

For close-ups, I used the 21mm lens, but the main shooting was done with the 14.5mm lens so I can still see the environment even when focusing on a character's face.

You're not concerned about distortion when getting too close with a 21mm lens?

No, because these are lenses designed for 35mm. When you translate it, the 14.5mm becomes more like a 28mm.

Yes of course, you're essentially using the center of the lens at that point. Were you involved with the color grade?

Not really; Eddie took that over. Once he has the edit, communication essentially stops; he works on it in his own world. I had established a look for the dailies, and I conducted tests so we had a roadmap for the visual direction. The team at Spectra Film in Los Angeles handled development. [Gotham Industries handled dailies, film scanning, digital Intermediate, and 16mm-to-35mm optical-blow up release prints for theaters.]

You spoke earlier about "going extreme." What was the most extreme approach you took in terms of the look of this film?

The daring part was placing the actors in complete darkness. We would sometimes expose only the legs while keeping the upper body silhouetted. We didn't light the background; it was almost like they were emerging from a black curtain. The lighting wasn't merely a tool; it functioned like a character in the movie, underlining the emotional context.

That seems extreme at a time when many are leaning towards a more subtle approach.

I chose darkness because it suited the story, not because "dark is cool." I see a lot of films that seem almost generated by AI — a copy-paste look that leans dark because it's the trend, not because it serves the narrative. In projects like Fuckkkyouuu, The Vandal, and Divinity, the lighting approach varies based on the emotional tone. It's all about where you place the emphasis; it needs to align with the story.