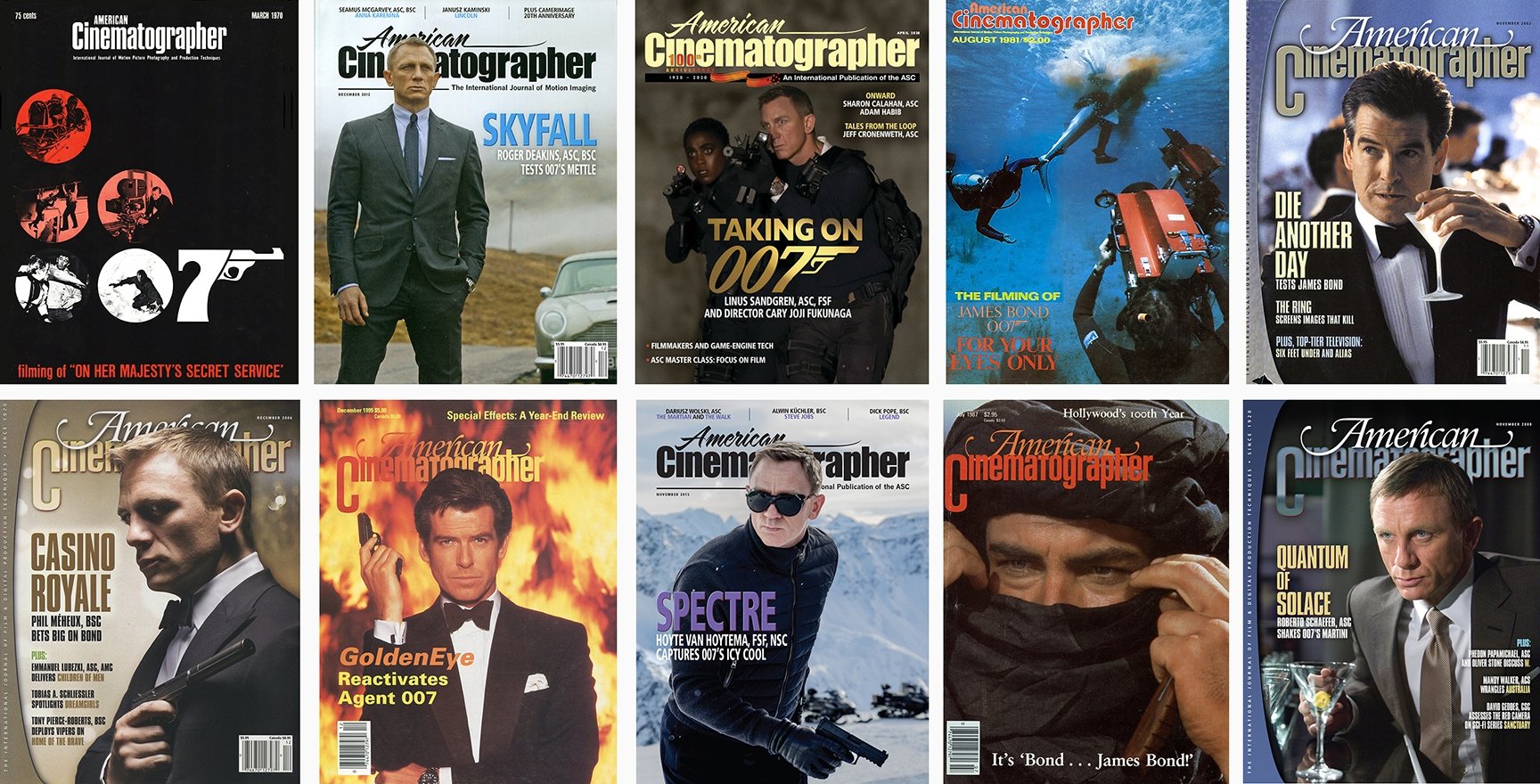

GoldenEye: Reintroducing Bond... James Bond

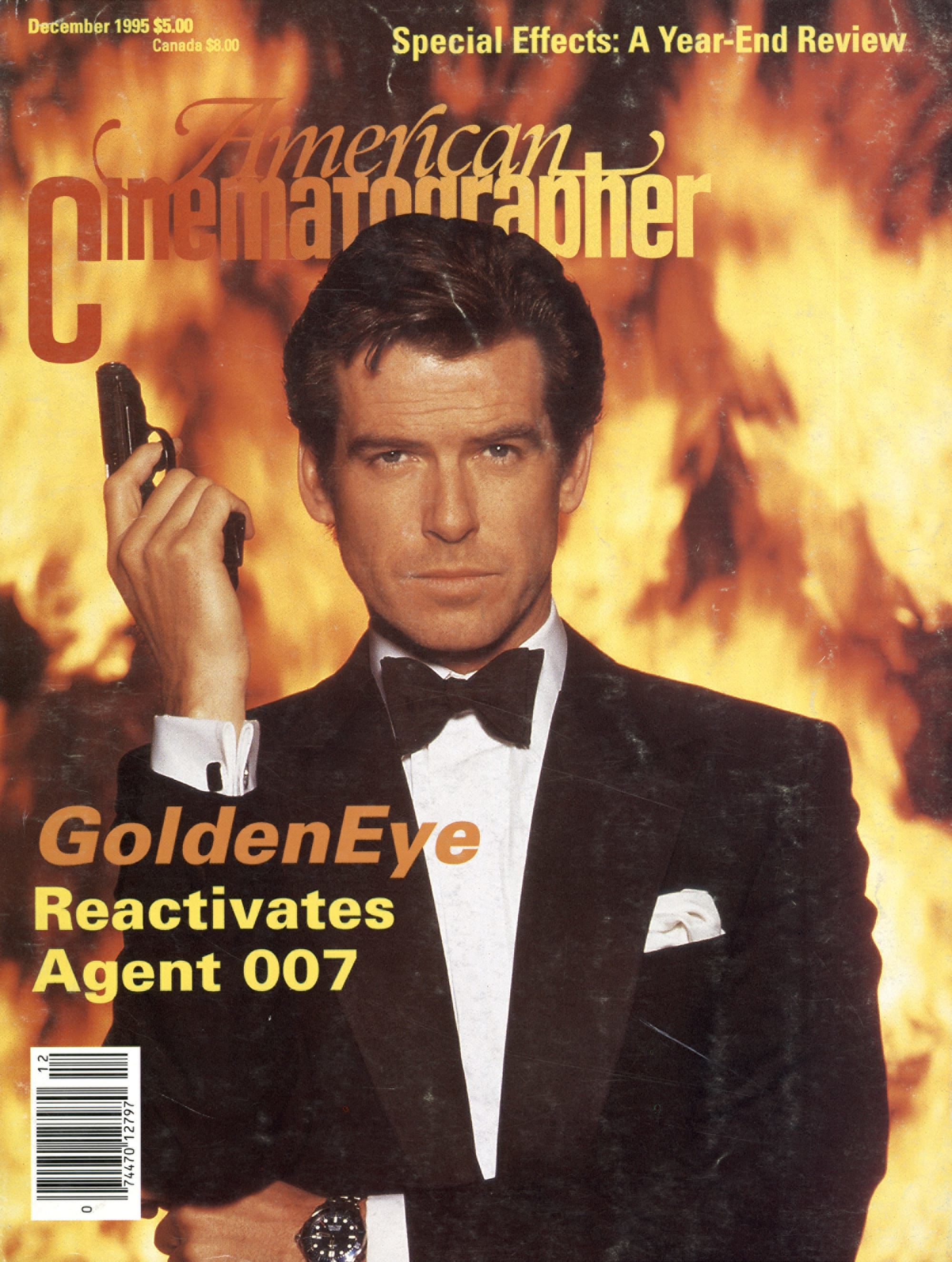

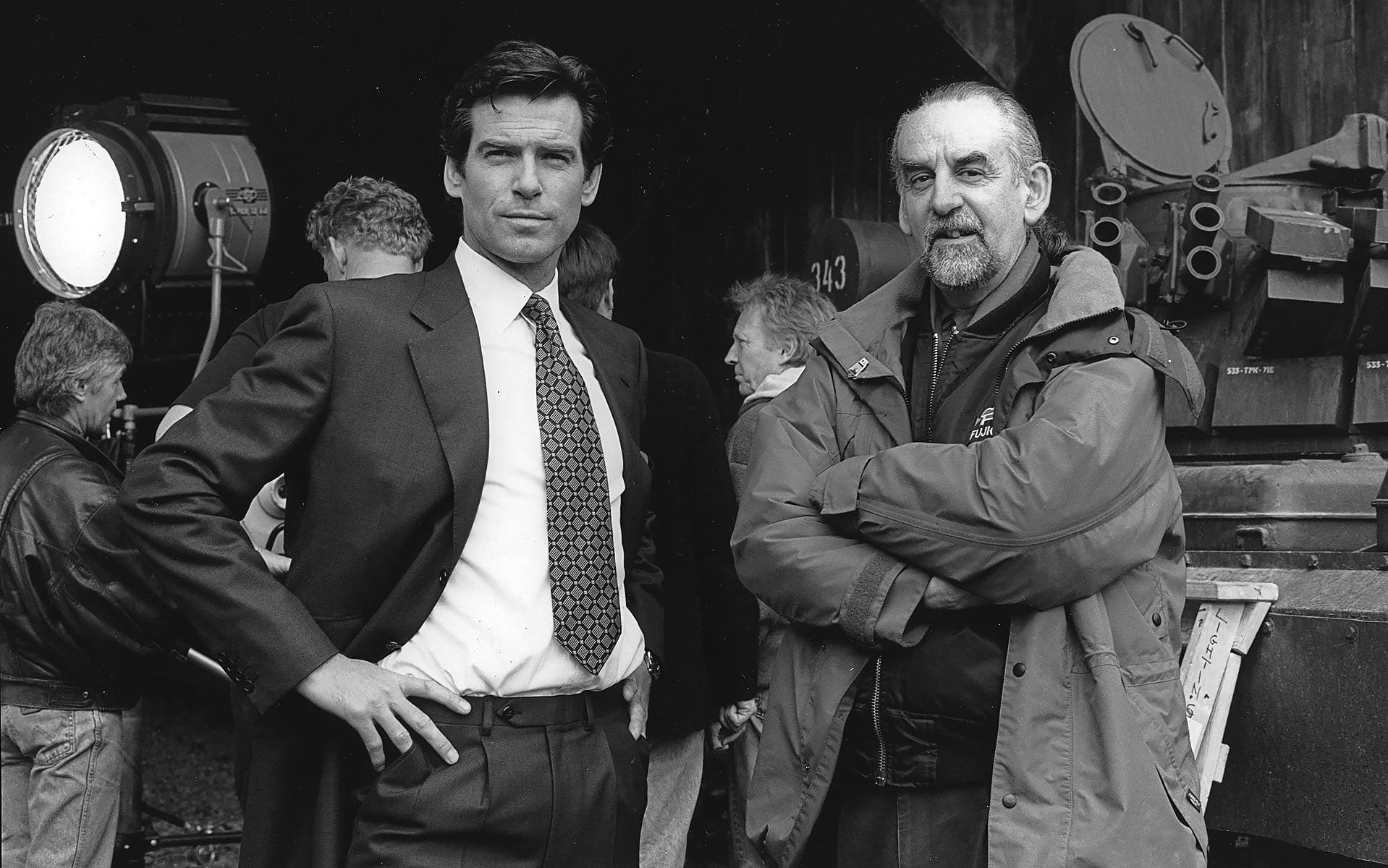

Director Martin Campbell and cinematographer Phil Méheux, BSC renew 007’s license to kill in a new adventure replete with the action and glamour that has made the long-running film series famous.

Unit photography by Keith Hamshere and George Whitear, courtesy of United Artists

If it was good for anything, the Cold War at least offered grist for the high-adventure film mill, resulting in the enduring, influential and entertaining James Bond series — beginning in 1962 with Dr. No and last updated in 1989 with License To Kill. But while recent developments in geopolitics may have spelled obsolescent doom for the real cold warriors within Her Majesty’s Secret Service, novelist Ian Lancaster Fleming’s dashing Bond character has found the New World Order chock full of worthy foes to thwart.

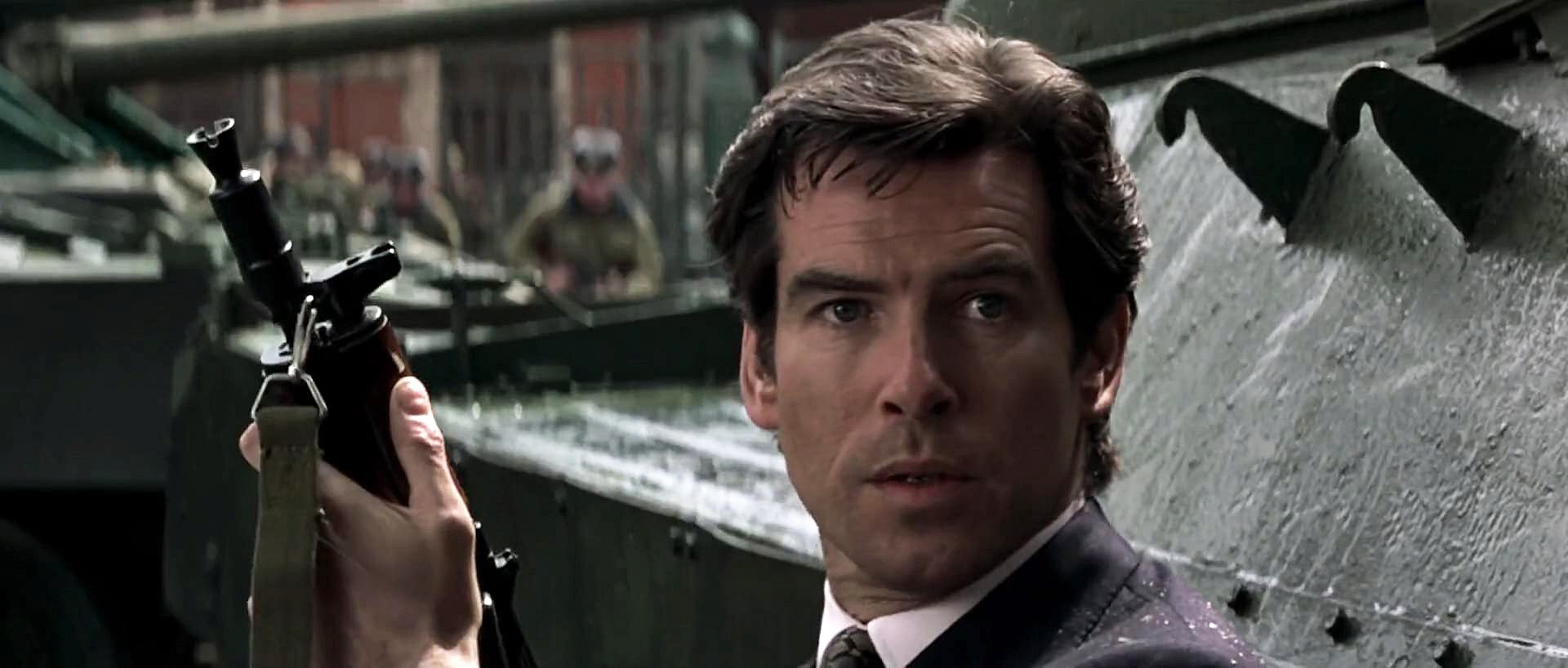

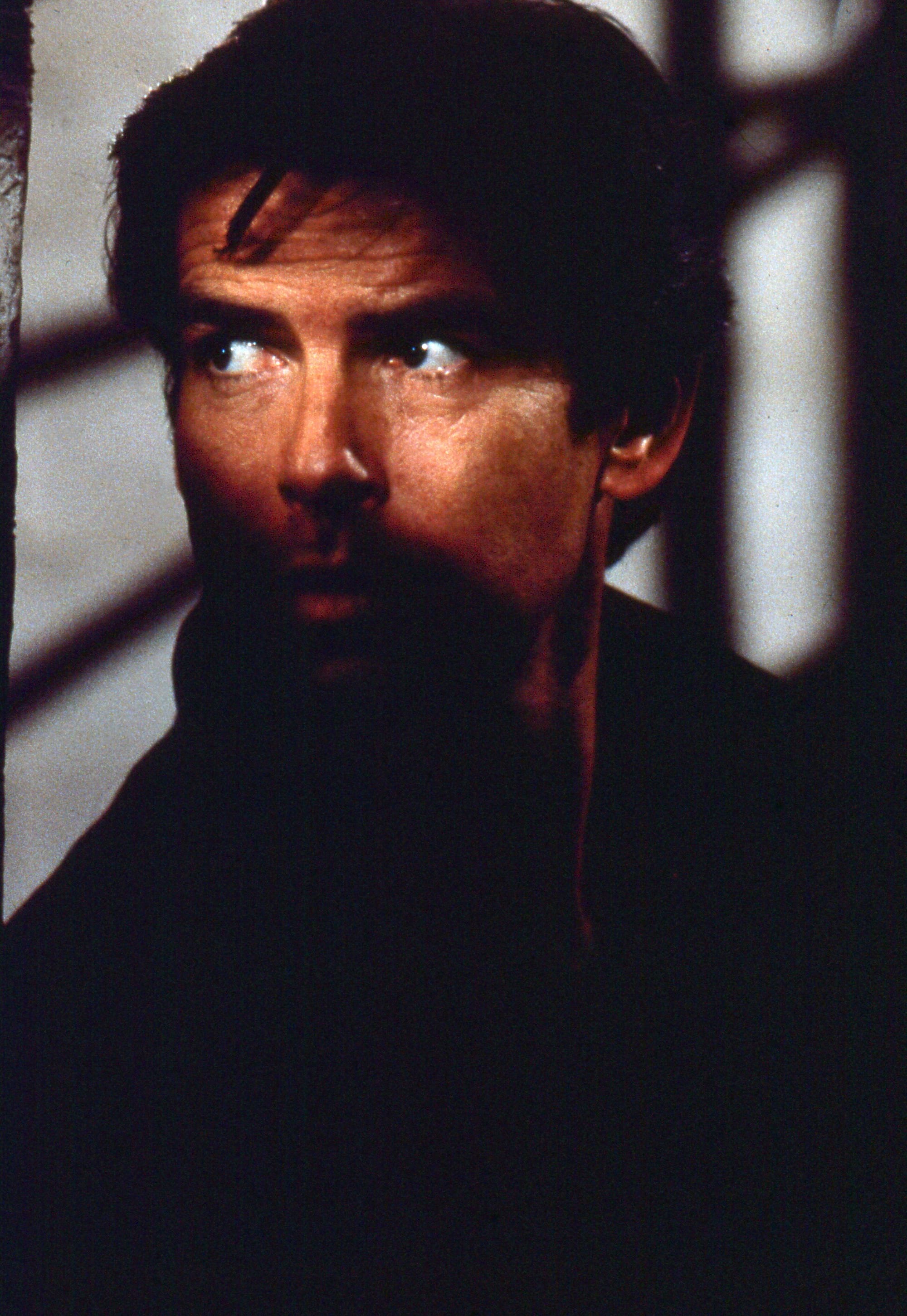

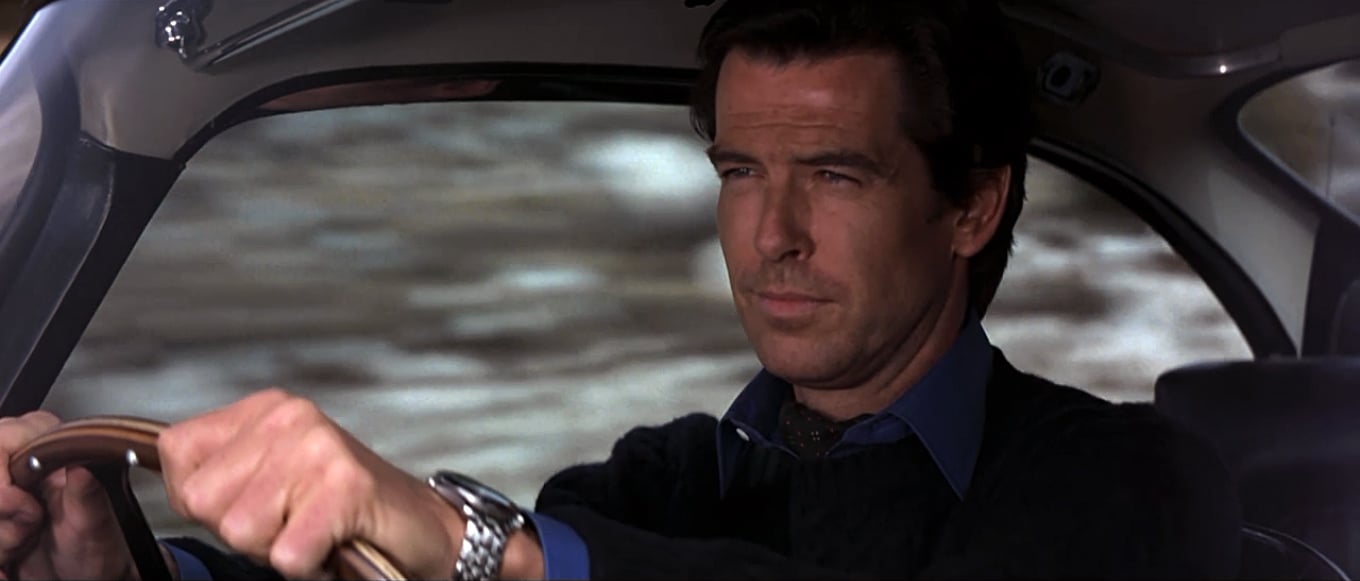

GoldenEye, the 17th 007 adventure, finds the globetrotting, vodka martini-drinking super-spy (Pierce Brosnan, the fifth actor to take on the coveted role) faced with a high-tech Armageddon, as the titular ex-Soviet military satellite falls into the wrong hands. One blast from its super-destructive electromagnetic pulse weaponry will wipe out a country’s electronic infrastructure forever. Neither SMERSH nor SPECTRE is behind this fiendish plot; this time, the covert cabal is the all-too-real Russian mafia, which is willing to blackmail the world with GoldenEye’s ability to zap the Digital Age back to the Stone Age. And little does 007 know, but someone from his past is on their side — the supposedly dead 006 (Sean Bean).

Bond fanatics will also recognize “GoldenEye” as the name of Fleming’s beachfront Jamaican home, where he penned the innuendo-and-action-filled 007 novels between 1952 and 1964.

Escorting this typically outlandish premise (scripted by Michael France and Jeffrey Caine) to the screen are New Zealand born director Martin Campbell and British cinematographer Phil Méheux, BSC. The pair had initially met in the 1976 on Black Joy, a feature produced by Campbell which marked Méheux’s end as a BBC cameraman and beginning as a freelance cinematographer.

But as Méheux explains, his career in cinematography began much earlier. “I think the first film I saw as a child was Bambi,” he readily admits. “So I kind of latched on to cinema from that very beginning and it got to the point where my brother and I would go see everything. I was given film books at Christmas which had pictures of cameramen sitting on cranes, and I got more and more interested — principally in the movies coming out of Hollywood. Films like Scaramouche and Singin' in the Rain were terribly exciting. So I decided to get into making films. I wanted to be the guy swooping in on that crane, so I began to follow the careers of cinematographers like Harry Stradling [ASC] and Leon Shamroy [ASC] — noting all their films and which awards they had won. It became a question of figuring out how to get into the business — a question I was somewhat embarrassed to ask.”

Turning down further formal education, but armed with moral support from his mother, the 16-year-old Méheux soon found a position with at least a tenuous tie to filmmaking: as a clerk at MGM's distribution branch in London. Leaving after finding that there was no chance to transfer to the company's studio facility, he worked as a projectionist at a TV commercial house, during which time he met others with similar aspirations and began making films on 16mm. “We got very into Russian, Italian and German styles — suddenly we were very cerebral,” he laughs. Méheux then applied to a new BBC trainee program for assistant cameramen — only to find it impacted. He was later accepted, and “by luck and adventure” had found his way into his chosen field.

“It was important to retain the good things about the Bond image while still bringing it up to the Nineties in terms of visual style and look.”

— Phil Méheux, BSC

“In those days, the BBC was doing some important things. Ken Russell was a director there, as was John Schlesinger,” Méheux notes. “And with the advent of lightweight 16mm cameras, such as the Eclair, it became easy to make dramatic films on location. Although the BBC was originally set up to produce documentaries, directors there saw the advantage to shooting drama on film as opposed to doing it live with a three-camera setup in the studio. So that work started to expand.”

But due to low budgets, the film crews were required to fill several jobs. And on shows such as Spy and Dixon of Dock Green, Meheux quickly worked his way up from assistant/ focus-puller to cameraman/operator, getting his break as a cinematographer on a pop music documentary featuring Pink Floyd and plenty of psychedelic style.

After a time spent alternating between BBC drama and documentary work, Meheux was approached to shoot his first feature, the aforementioned low-budget 35mm project Black Joy. Meheux was convinced to leave the BBC to shoot the film by producer (and future GoldenEye director) Martin Campbell — creating the foundation of a long-running friendship. “We got on like a house on fire,” enthuses the cinematographer, further explaining that Campbell soon moved into directing for television.

“Having done 12 years of TV by this time, I was ready to move on,” Méheux says, “but I told Martin that if he ever had a theatrical feature, I’d be there for him.” This would ultimately lead to their collaboration on the thrillers Criminal Law and Defenseless, as well as the futuristic actioner No Escape.

The director of photography's other credits include The Music Machine; Out; Scum (a controversial youth prison film produced by Campbell); Those Glory, Glory Days; The Long Good Friday; his first American production, The Final Conflict (Omen 3); The Final Option; Experience Preferred But Not Essential; The Honorary Consul; the sci-fi comedy Morons From Outer Space; the independent Channel 4 feature Max Headroom, upon which the U.S. series was based; The Fourth Protocol; Renegades; Highlander II and Ruby. Campbell is also known for his work on Reilly, Ace of Spies and the series Edge of Darkness. Following those projects, Campbell moved on to make his previously mentioned pictures with Méheux, as well as HBO's supernatural noir film Cast a Deadly Spell. The director says, "It's always difficult to know how things like this happen exactly, but MGM/UA then called regarding Bond."

“Martin and I were both in Los Angeles and he was a bit perplexed by the offer,” says Méheux of the duo’s first reaction to being invited on board the GoldenEye express by producers Michael Wilson and Barbara Broccoli (who are, respectively, the stepson and daughter of long-time 007 producer Albert “Cubby” Broccoli). “Martin wasn’t sure it was him, but he said, ‘The Bond films have such a particular feel and style — let’s get them out for a look.’”

Jokes Campbell, “I wanted to see just what the hell I was getting into.”

“We decided that the earlier ones were much better in several ways,” says Méheux. “In the Sean Connery films, Bond’s character was much stronger and much more believable as a spy. The set design [by Ken Adam] was revolutionary — they created a world of their own — and Ted Moore [BSC], who shot seven Bond films, achieved a definite visual look. Martin and I didn’t want to mess with that too much. It was important to retain the good things about the Bond image while still bringing it up to the Nineties in terms of visual style and look. Because while there is a huge audience out there for Bond, I think there’s another one for a newer Bond.”

“The early films creak like mad, but Sean Connery was so bloody charismatic that there was no getting away from it — which is something I think we brought back with Pierce Brosnan in the role.”

— director Martin Campbell

Explains Campbell, “The series has been so incredibly successful and there are a lot of ingredients in those stories that work, though to a lesser degree in the later films. The humor, the Bond character and certainly the glamorous women have a hell of a lot to do with it — in addition to the big action sequences. But also interesting is that you have a hero who has a killer instinct yet is attractive to both women and men. He’s the antihero in the bow-tie and dinner jacket.

“Granted, the early films creak like mad, but Sean Connery was so bloody charismatic that there was no getting away from it — which is something I think we brought back with Pierce Brosnan in the role.”

Remarks Méheux, “To his credit, Brosnan has done extremely well. He and Martin have tried to bring back the image of a proper spy who knows what he’s doing.”

Also brought back with GoldenEye is the moodier feel of the first Bond films: Dr. No, From Russia With Love and Goldfinger. “They had more character in the lighting,” Méheux concedes, “although they weren’t exactly low-key, principally because the stocks they had — still relatively primitive and new even in the 1960s — were only about 25 or 50 ASA. So they required more light and much lower contrast in the lighting to be safe.” Characterizing some of the later entries in the 33-year-old series as too high-key and “flat” for his taste, Meheux turned to his mentors for aesthetic guidance, pointing out how great cinematographers can profoundly affect the emotional content of a film.

He offers, “For instance, the last scene in The Long Voyage Home, which Gregg Toland [ASC] basically lit with one brute arc lamp, is a moment of great cinematic artistry — a cloud passes over the ship our main character is standing on, first casting him in silhouette and then in darkness. He has just discovered that all of his friends have died, and the lighting reveals all of his feelings. John Alton is another inspiration for me. Working on so many low-budget films, like T-Men, he developed a tremendous ability to light a set with one lamp, which I find very exciting.”

“It’s much more evocative than blood bags bursting out of people’s shirts in slow-motion.”

Méheux also recalls a famous sequence from The Killers, in which a pair of hitmen, seen in silhouette, mow down Burt Lancaster with bursts of gunfire; the muzzle flashes illuminated their faces, courtesy of Woody Bredell, ASC. He holds equal admiration for Alton's technique in a similar shot in The Big Combo, which cuts directly to a limp hand dropping a cigarette to the floor. Méheux adds, “It’s much more evocative than blood bags bursting out of people’s shirts in slow-motion.”

“Lighting your actors is based on what their character is supposed to be and where they are.”

Specifically, Méheux says, “Most films seem to have a very natural look today, which I find quite disappointing. There always seems to be soft light coming from one direction or another, with no definite artistic overlay on the film. But it’s only of late that this began to happen. A film as recent as Star Wars, for instance, still had good lighting, but it just doesn’t seem required anymore. With our scheduling today, we’re in the age of the ‘setup.’ The more setups you get a day, the better, no matter how they look — which leads to this soft, overall lighting that doesn’t really make any kind of statement. It doesn’t add to the nature of the film, which reduces the importance of the cinematographer’s role in the filmmaking process.

“But good photography is no good without a good director,” he adds. “It seems as if certain directors now are coming out of being writers, and they have a lot more interest in the dramatic content than the visual look of their films. It’s as if we are just recording what’s going on in front of the camera.

“We tried to retain the darkness and glamour aspect of the old Bond films — the women always looking good, the men handsome.”

“That worries me, though I also think if the dialogue is terrific and the performance great, the camera should be static. It doesn’t have to be wobbling or moving left and right for some effect. The important thing is that you’re telling a story, and the way you are going about it should be hidden and not visible. So I really feel the best filming work was done 30 or 40 years ago in pictures like The Third Man, Brief Encounter and Gone with the Wind — they were masterpieces. And there are very, very few masterpieces being made today.

“In fact, GoldenEye very much resembles The Third Man thematically in that the story is also about someone who is not supposed to exist, but who does exist. There is a scene in our film that takes place in a sort of cemetery for statues of the old Soviet regime in Russia, and I tried to give it a sort of Third Man look — Robert Krasker is a hero of mine. But I suppose that film has been influential on all of my work, in terms of the simplicity of the lighting. I'm constantly remembering lighting effects from black-and-white films. I mean, Citizen Kane has probably influenced every filmmaker on the planet, and I can vividly remember every single inch of some sequences.”

Relating these influences to his work on GoldenEye, he concludes, “We tried to retain the darkness and glamour aspect of the old Bond films — the women always looking good, the men handsome — and the rich opulent settings Bond always finds himself in. At the same time, we utilized modern camera movement and — I’m almost ashamed to say — more setups to create more excitement for today’s audiences.”

Regarding the transformation of action editing and pacing in light of such recent action pictures as True Lies, Campbell says, “Well, James Cameron is about the best at action, no argument; he’s tremendous. What you learn from him though — besides noticing that the action is hopelessly slow in the early Bond films and also the later ones with Roger Moore — is that you really need a terrific stunt coordinator to create scenes that can bear the scrutiny of so many cuts and setups. We had Simon Crane, who also did Braveheart. But you also need something different. How many car chases have you seen? And how many do you really remember, aside from The French Connection and Bullitt? Both of those chases had terrific focus, making them superb action as opposed to chaotic destruction. Cameron got his difference [in True Lies] with the Harrier jets, but we have a sequence that is different too.” Cryptically, he declines to describe it, but says the scene “plays into the nature of action in the Nineties. It’s faster, fiercer and more relentless, a change that probably started with the first Terminator film.”

“All the later Bonds have been anamorphic 2.35:1. It’s the big screen, and that’s what action films are all about.”

Adds Campbell, “It’s a bit daunting to alter the nature of the Bond films because you have to live up to the expectations of an audience. In addition, we had to decide how to revive the series in terms of story — as the last two went a bit downhill. The series was tired, so we had to design our visual approach to help revive it. This is a far moodier film than those from the past, and what Phil has done is very unusual for Bond films — working very dark and gritty in some scenes, but retaining a highly-polished look overall.”

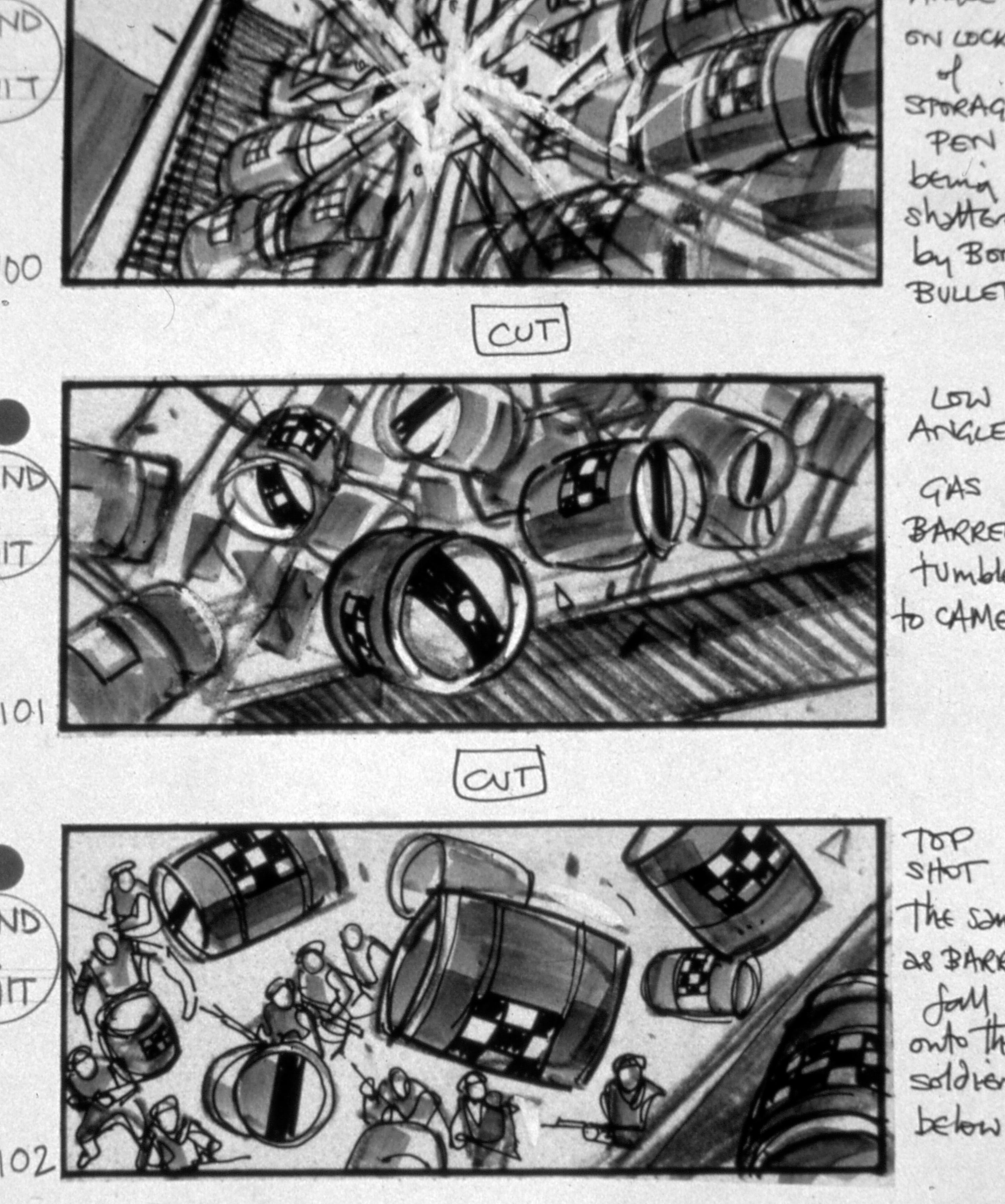

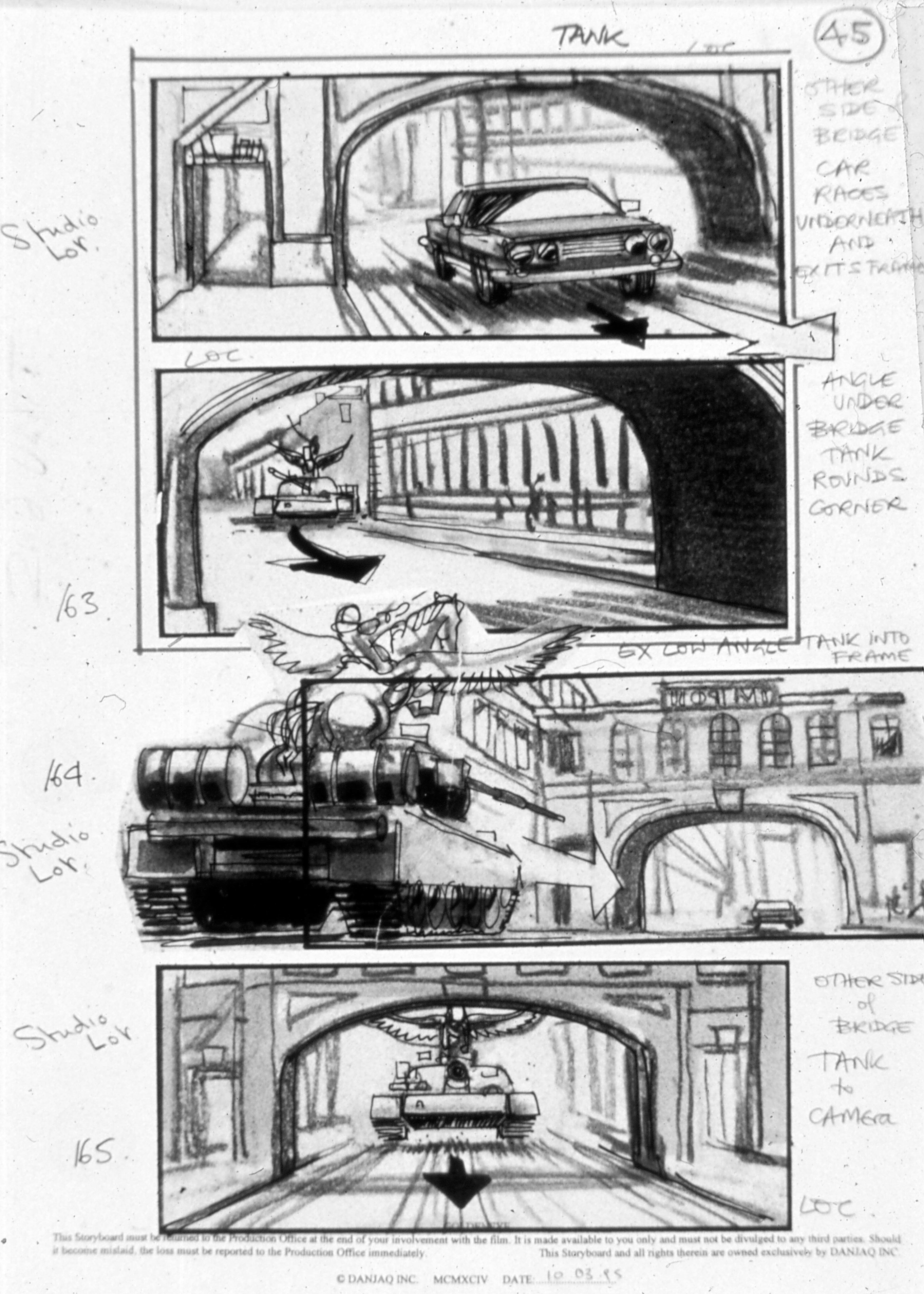

One of the early stages in developing the final visual approach to GoldenEye was storyboarding. “I did it all myself with the help of an artist,” Campbell says. “Not the dialogue scenes, but certainly all of the action and effects sequences. The organizational task of doing a picture like this demands it. And given that our budget [reportedly $55 million] was far below what an American production would have, we had to be careful.” The boards were later presented to Méheux for his input. Referring back to the Soviet statue warehouse scene, Campbell says, “That was Phil’s. It wasn’t storyboarded and he way he lit it was magnificent.”

Méheux then tackled the fundamentals of achieving their strategy, beginning with his choice of frame. “All the later Bonds have been anamorphic 2.35:1,” he says. “It’s the big screen, and that’s what action films are all about.”

Campbell backs that notion up, enthusing, “I happen to love anamorphic. It’s a pleasure to frame things that way and it’s great to see more films being shot that way, although some hardly need to be.”

With the format decided, Meheux concentrated on selecting camera gear. The decision to use Panavision was almost as inevitable as the prospect of going widescreen at all, dictated primarily by lens availability — though the fact that every Bond film since Thunderball (1965) has been shot with the system may have been a subliminal factor. But before detailing that process, the cinematographer takes up the issue of Panavision’s relatively infrequent use on European productions, stating plainly, “It’s too expensive relative to the budgets we’re working with here. We just don’t have the money Hollywood has, so we can’t just spend to get the best there is. We’ve had to experiment more with cameras, lenses and film stocks to keep our budgets down. But I chose Panavision for GoldenEye, although I have shot three other anamorphic films using a system devised by Joe Dunton & Company, an English firm that makes anamorphic fronts for old Cooke lenses. They’re great, but the problem was that they are all BNC mounts. It’s difficult to find a modern camera that will take the lenses — Panavision surely won't — though now that’s been corrected with the MovieCam."

Méheux notes that he had previously used Panavision on The Final Conflict (Omen 3), an experience that put him off because he had difficulty finding lenses with matching quality. “After that, I tested all sorts of anamorphic systems — Technovision and others — and I finally found Joe Dunton’s lenses and thought they were terrific. I was quite keen to use them again, but there are only three sets. So we turned to Panavision. They gave us the lens availability we needed to supply five units, three shooting continuously. We cleaned out the rental house. The first and second units had two sets of primes each — so we had a total of eight sets in use. Panavision was simply the only company where I could find the continuity in lens quality that we needed.

“There were only two sets of Primos available to us, one each for first and second units, and one Primo zoom. The model and second units were using Es and I also had Cs, because they were much smaller and I could use them for handheld, Steadicam and cramped spaces.”

Méheux's first unit utilized a Platinum Panavision and had a GII as a back-up, while the key lens for the shoot was a 40mm, which he qualifies as a “good wide angle that doesn’t distort — which draws the audience into the picture by giving them more to look at.” He further reasons, “It’s a shame that most films rely so much on tight close-ups all the time, filling the screen with an actor’s head like you might for television when there is so much more you can show. The style is really just a result of what producers want for video release. But you just don't need a tight close-up when you have a screen that’s 60 feet wide.”

Méheux kept his stop at about f4, reasoning that shooting further open invites problems. “You’re only enhancing the qualitative differences between lenses by stretching them to their limits. Besides, if you have a 60-foot-wide screen, why just have an eyelash in focus?” Helping out here was Kodak's 500 ASA 5298, which easily gave him that stop without his having to use “acres of light” or resort to “burning holes in actors’ faces.” Méheux observes that 98’s grain is nearly imperceptible and the advantage in speed outweighs any disadvantages. Kodak’s 200 ASA 5293 was employed for most exteriors. As Meheux notes, “The sun may shine a hell of a lot in California, but it doesn’t in England, especially between January and May.” So 93 covered the bases, as Meheux “wanted a stock that could be used all day long.” He adds with a laugh, “When we get a cloudy day in Britain, it might as well be night.”

On location in Puerto Rico, the filmmakers used 50 ASA 5245. “It was sunny,” he says. As for speed ratings, Méheux explains that he underrates 98 to 400 ASA at night, or even lower, as “there's nothing worse that a night sequence where there aren't any blacks. But you have to adjust to prevailing conditions.” Not incidentally, he mentions that he uses the lab to help him make rating evaluations, saying, “I like my printer lights to be in a certain position and I ask them to tell me if I start wandering.”

Remembering the Primo zoom in his lens arsenal, Méheux guesses it was employed “maybe twice over 126 days of filming. To use a zoom in anamorphic, you really do need about four times more light than you would for a prime. So unless you need it for a reason, it’s not practical, especially on interiors where you would have to bump your light up a hell of a lot.

“But zooming to me is usually just sloppy operating. There should be a way of designing any shot with camera movement and blocking to achieve the framing you want without zooming. Martin agrees with that, and we were wondering if we would need it at all. Oddly though, I used the zoom because it focused closer than the fixed Primo lenses. I told the guys at Panavision that it’s the one problem with their primes — they don’t focus close enough. One of Martin’s dramatic devices is to start wide and then go thundering in to end up on somebody’s face in tight close-up. So this focal distance issue became somewhat of a problem with the fixed lenses because we would end up just a bit too far away, focused at three and a half feet. But we found, at least on one lens, that the focus deteriorated when on its limit. With the 5:1 Super Panazoom — which is actually a Cooke T4.5 lens — we could get the focus right on these tracking shots, at two and a half feet.”

Asked if this focus question was also a issue with the Steadicam work on GoldenEye, Méheux takes a breath before opining, “I’m probably going to upset a lot of operators, but the Steadicam is a tool that needs to be used on very rare occasions, although now people have the notion that it can be used to speed up the setting-up process. But if you have a good crew — and I’ve had plenty of them in Los Angeles, London and Australia — it doesn't take two minutes to lay tracks and get a dolly shot done right. What I don’t like about Steadicam is that you can’t lock the frame off. You never get the composition that you really want because there are the two or three seconds there when the operator adjusts to having stopped after a move. So he’s floating very slightly and if he’s two inches off his mark, there’s nothing you can do about it. Your shot is now off, whereas if you’re on a dolly and track, you know exactly where you are and where you're going. I like the formality of fixed-lens shooting. And while it may sound old fashioned, I like the formality of saying, ‘What is the right lens for the shot and where do we position people in the frame?’”

As a result of this philosophy, the Steadicam was rarely used on GoldenEye. But Méheux concedes, “The Steadicam is great if you want to track forever; it’s the only way to do the shot. Take GoodFellas or Bonfire of the Vanities for example. The famous shots in those films were terrific and could only be done with a Steadicam.”

Was the notion of shooting Super 35 ever considered? Sparked, Méheux insists, “Anamorphic is far superior, and to me, Super 35 never looks right. People point out Terminator 2 and The Abyss and that James Cameron is a big supporter of it, but he’s also the only one. Maybe he has tremendous control over his prints, because when anybody else tries it, the result looks terrible when it gets to the release print stage. The rushes look terrific, but you ultimately get this grainy print with no blacks in it. But there is an elegance to an anamorphic film, principally because you're using a longer lens to shoot a wide image. Your standard lens is a 75mm instead of a 35mm; it gives you a much more elegant framing.” Pondering the intangible, he adds, “I just get a feeling from anamorphic cinematography and I remember the images more clearly. Super 35 looks like the top and bottom have been cut off, whereas in anamorphic the frame has been widened.

“Of course, there is always the fact that in Super 35 you will never see a straight print off the negative. Ever. It’s always an optical. At least I know that at the world premiere of GoldenEye with Prince Charles there, we’re going to have an original negative print and it will be as sharp and as grain-free as we can get it.”

As for filtration, Méheux debunks the notion that Primos are too sharp to be used without diffusion. “If the picture is too sharp, either the make-up is not right, the lighting is not right or the size of the shot is not right,” he says. “Lighting your actors is based on what their character is supposed to be and where they are. And if you can’t light right, you put a filter over it all to distract the eye. Besides, you have to remember that any effect is only going to be magnified by the time it gets to the release-print stage, and if the picture is fuzzy, the grain stands out.”

Is Campbell a highly technical director regarding cinematography? “No, he’s not," Méheux says. “Martin instead submerses himself in the layout, the cutting and the setups. He doesn’t know about lighting or how the photography looks until he sees it the next morning in dailies. He leaves that all up to me. He’s much more into how cuts work. Unlike many directors today, though, he shoots what he needs, as opposed to shooting every possible angle and fitting it together in the editing room. That may be difficult for a producer who wants to get his hands on things later, but it saves time in the shooting because we know where we're going. But that’s what I like about Martin — he's very well prepared. So that makes for a smoother, faster shoot as we don't have to dither around thinking about what we're doing.”

Suggests Campbell, “That’s my background in television — you just have to be prepared. You learn to always shoot in the direction of the light, plan your shots, rehearse and then make the system work. And we got that down to a fairly sophisticated stage in GoldenEye. We never got trapped by bad organization.”

Maintaining visual consistency while juggling five units shooting around the globe can be tricky. Says Campbell, “Fortunately, we had good people, although sometimes it became an issue of sitting down and saying, ‘Well, where the hell are the storyboards?’”

Méheux elaborates: “Certainly the model unit’s job was very well defined, but the second unit’s work was more of a problem because we were following their lead on several scenes.”

A case in point was GoldenEye’s tank chase sequence, during which 007 hijacks a Russian T-72 main battle tank and pursues his quarry through St. Petersburg — destroying plenty of things along the way. The sequence was staged by second-unit director Ian Sharp and photographed by Harvey Harrison, BSC, first on location in St. Petersburg and then on sets built in England. “I knew Harvey quite well personally, and he knows what I like to see,” Méheux says. “So I would just shoot matching close-ups later to match their footage.

“The usual problem with second unit is that most good cameramen don’t want to do it. But while talking it over with Ian, Harvey’s name came up. I didn’t think he'd do it, but I rang him up and asked, “So, tell me, Harvey, are you too famous to shoot second unit on GoldenEye?’”

Though he had wanted to become a farmer as a youth, Harrison was seemingly fated to work in the film industry. As he explains, “My great uncle was William Friese-Greene, who some believe invented the movie camera; my grandfather was a scientist, a pioneer in color film here in Britain; and my father was a director and cinematographer who spent the World War II years making RAF training films to teach pilots how to fly Spitfires. He continued making documentaries and films afterwards. So, at 17, I asked my father if I could become a cameraman.” The answer surprised Harrison, who suddenly found himself thrown out of the house and told to find a job on his own. After a few weeks, he landed his first as a tea-boy at a TV commercial studio. “I was very lucky, as all of these great cinematographers were working there, like Geoff Unsworth and Nicholas Roeg; I ultimately shot three films for [Roeg] after he began directing. So it was a fortuitous start.” Harrison's credits include Roeg's segment in the vignette film Aria, as well as The Witches; he has also shot Salome's Last Dance for Ken Russell and a multitude of commercials.

A former president of the BSC and current president of IMAGO, the European Federation of Cinematographers, Harrison recalls Méheux’s initial inquiry and laughs, “He thought maybe I was too high and mighty to shoot second unit, but I quickly dispelled that notion. I’m just a working cameraman like the rest of them. So I was delighted and honored to be asked. But this wasn’t so much like mopping up after the first unit. We had real sequences to get our teeth into, and that’s what attracted me.”

The tank chase was by far the most difficult. “It was five weeks’ work and ultimately will last five minutes in the final cut,” Harrison says. “We nicknamed the tank ‘Metal Mickey’ — at 42 tons, it didn’t stop for anybody. We had 10 days in St. Petersburg and then shot for the balance at our stages in Leavesden.”

“The sequence was completely pre-planned by Martin, Ian, stunt coordinator Simon Crane, Phil and myself,” Harrison details. “That alone took several weeks before the picture started, because there was a lot of stuff we could only do once, like knocking down various buildings and flattening cars. So on any major stunts we did with the tank, we used a minimum of four cameras, and on one occasion six. Our main cameras were a Panaflex Gold, two Arri III's, and one Arri IIIC. We had them all the time, with a full set of Primo primes, 10:1 and 5:1 zooms and some long 400mm and 600mm anamorphic lenses.”

Harrison notes that the tank was shot at various frame rates to give it the illusion of additional acceleration and maneuverability. “The first unit then came in and shot inserts of Pierce Brosnan in the driver’s seat, changing a few gears and making a few faces,” Harrison adds. “I’d shot several times in St. Petersburg, and it’s a wonderful city. We had a couple of problems getting permission to do certain things, but remember, we were driving a tank at full speed down main city streets. Try doing that in New York City or down Sunset Boulevard.”

Preparing for the unpredictable weather in England, where the rest of the sequence would be shot, Harrison was careful to “shoot bits in sun and bits in dull weather just so there was a chance it would match what I might get later.” Taking careful notes on atmospherics and sun position would also pay off. “We were lucky with the weather, although we did have to bring out two 18K HMIs, two 16K HMIs and a bunch of 10Ks for adding sunlight back home.”

According to Campbell, though, “St. Petersburg was a pretty dull place. Harvey was lucky to find any sunlight at all. But, fortunately, England is also very dull for the most part, so the matching wasn’t too much of a problem.”

While Pinewood Studios has traditionally been the home of the Bond productions, GoldenEye couldn't find enough space at the facility to suit its schedule — even though the production company owns Pinewood's legendary “007 Stage,” which was originally built in 1976 for The Spy Who Loved Me. But the filmmakers found a new home outside of London in the town of Leavesden: a converted industrial complex with 1.25 million square feet of available interiors. “It was a Rolls-Royce aircraft engine factory,” says Méheux, “which had been there since World War II and was built on the edge of a runway. After looking at studios in other countries, we settled there. It had plenty of space, and we really wanted to shoot in England.”

Four months before shooting would begin, Méheux and his gaffer were summoned to Leavesden to give their recommendations on how the sprawling array of buildings and open space could be best used. Five stages were sound-proofed and fitted with lighting scaffolding, a separate model stage was built and portions of existing structures were minimally made over to portray a Russian military barracks. Since GoldenEye wrapped, the Leavesden site has been purchased and will possibly become a permanent shooting facility. [Now owned by Warner Bros.]

“You can’t really call it a studio,” says Harrison, “but it is an amazing situation there, with 260 acres of land and a great collection of buildings. And they transformed it quite well, though it doesn’t quite have the height you might ask for. I really believe it will catch on.”

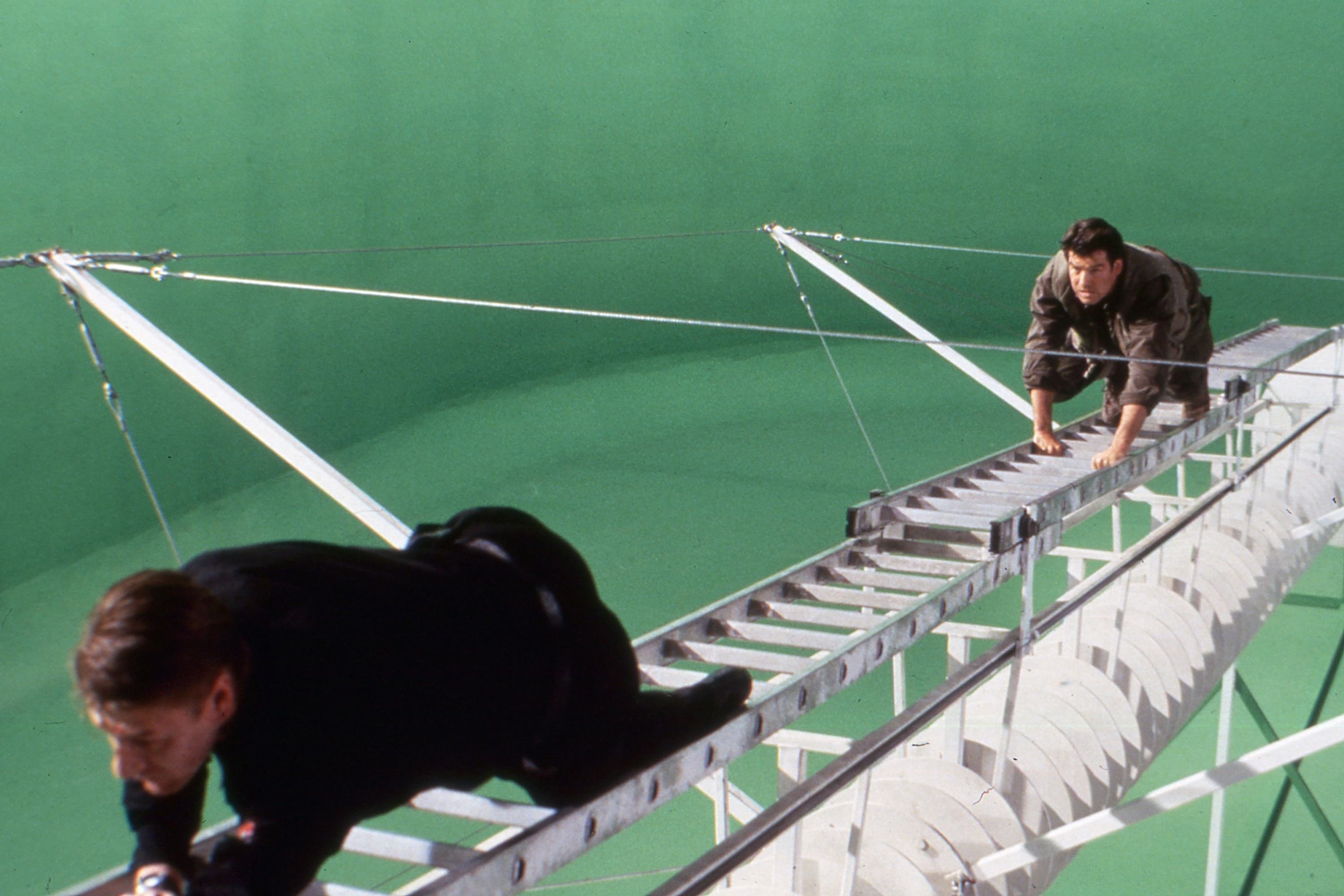

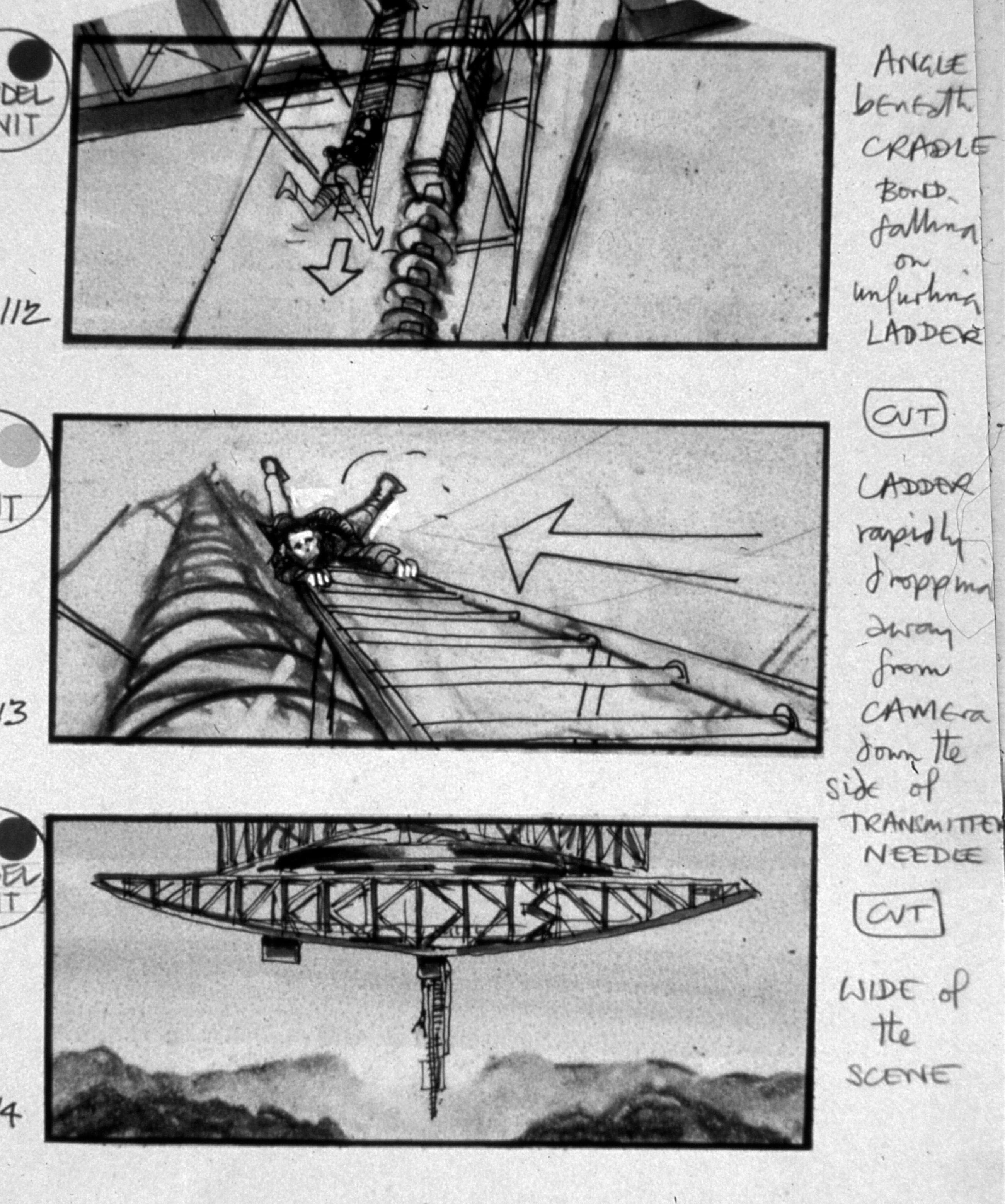

Recalls Méheux, “Another case where communication became critical for all of us was for a fight scene at the end of the film [between Bond and 006], which takes place at the huge radio dish antenna in Arecibo, Puerto Rico. It happens on the hanging portion 500 feet above the 1,000-foot-wide dish, and on the dish itself. We weren’t allowed to shoot on the dish, and could only have access on Sundays; there were a lot of restrictions. The second unit did wide shots with doubles and shot plates, and Derek Meddings’ model unit built a superb miniature for certain shots which were terrifically photographed by Paul Wilson. We did the main part of the fight on a greenscreen stage.”

Studying Campbell’s storyboards, Méheux devised sketches detailing sunlight direction and basically “broke it down shot by shot.” He placed particular emphasis on lighting schemes for the first unit’s stage work, as that’s where the bulk of the fight would be photographed.

Méheux notes, “The greenscreen was lit with conventional tungsten light, then we had a separate crew shoot a number of tests to see how ‘badly’ we could light it before the greenscreen broke up on the computer. This helped me know how much I should worry about it and when I could leave it alone, Logistically, the nine-ton antenna set had to be rigged at four different angles to allow for the action to work and we didn't want to have relight the green backings each time.”

Harrison reports that 5245 was used for both the second-unit footage and plates.

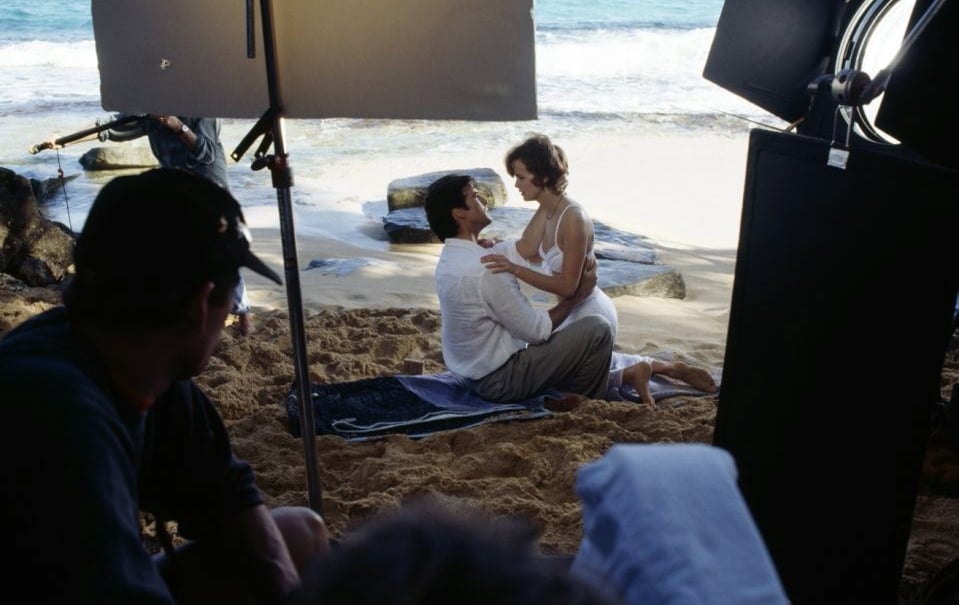

Shot in Monte Carlo was a chase between Russian assassin Xenia Onatopp (Famke Janssen) in a Ferrari F355 and Bond in his traditional car of choice, a custom Aston-Martin DB-5:

Says Harrison of the camera chase vehicle, “We used a completely new system based on a Land Rover four-wheel drive truck.” Constructed by Barbour All-Terrain Tracking in Surrey and dubbed the BATT, the high-performance rig boasts a 4.2 liter Rover V8 and is capable of onroad speeds of up to 100 mph — with 10 speeds forward and two in reverse. In addition, the BATT’s suspension has been heavily modified to reduce vibration and features an adjustable shock absorber system.

The BATT was first used for shooting battle sequences in Braveheart and “it could out-accelerate both the DB-5 and the Ferrari,’ Harrison says. “But what’s really terrific is this hydraulic lift that can be mounted on the back or sides; you can put the camera from nine inches above the road to 10 feet high in just three seconds. We used that together with a three-axis stabilized mount called the Libra II.”

Built by the Shepperton Studios-based company Megamount, the joystick-controlled Libra II can pan or roll through 350 degrees and tilt 25 degrees either side of horizontal. It was also recently put through its paces on Braveheart and Ridley Scott film White Squall. Continues Harrison, “You put an Arri III in there with a 5:1 zoom, and you can go over any kind of ground with complete stability. We got some remarkable footage for that chase, and we used the Libra to good effect on the tank sequence as well.”

The BATT/Libra II rig also diminished the need for a Steadicam on the second unit’s shoot,“though we did do a single POV shot with one,’ Harrison recalls. “But all of the second-unit work was very carefully done, as Phil and I agreed that the quality of the film should be in every shot. I remember there was an insert we needed of these keys that activate the GoldenEye satellite. Phil just said, 'Make it look like a commercial spot.' So we went for this glamorous, 'Bond' look and it really pays off in the final production.”

Not incidentally, another chase was staged in Puerto Rico, between 007’s new BMW and a Cessna light aircraft. Méheux reports that the film’s British crew was “terribly ashamed of” the agent’s new wheels — a Z3 roadster.

Looking back, Méheux says, “There’s been a long gap between this picture and the last Bond film [License to Kill in 1989], and during that time a lot of films have used the Bond style. The problem now is the impression that GoldenEye has to ‘beat’ these other films. But I think we’ve something rather unique here.”

Adds Harrison, “They’ve really upped the ante, and Bond will have a tough time keeping up. But we’ve made a bloody good try with GoldenEye. The action really goes and the character has the British coolness. He’s not a superhero like Bruce Willis is in Die Hard, or Schwarzenegger in True Lies. Bond has to be more realistic, even though he’s also something out of our wildest dreams.”

But is actually making a Bond film a dream come true? “I hate to say it,” confesses Campbell, after finally reaching the end of GoldenEye’s production after 18 months, “but it’s been a grind. A bloody nightmare. But we’re all proud, and, above all, Brosnan is the perfect Bond.” Pausing, he jokes, “Even though he’s Irish!”

A decade later, Méheux re-teamed with Campbell for the next major 007 reboot, Casino Royale (2006), starring Daniel Craig as the new Bond. Like GoldenEye, it would be another smashing success. (Complete AC story here.)

Méheux was honored with the ASC International Award in 2015.

You’ll find more of AC’s 007 coverage from our archives here.

For access to all 100 years of American Cinematographer reporting, subscribers can visit the AC Archive. Not a subscriber? Do it today.