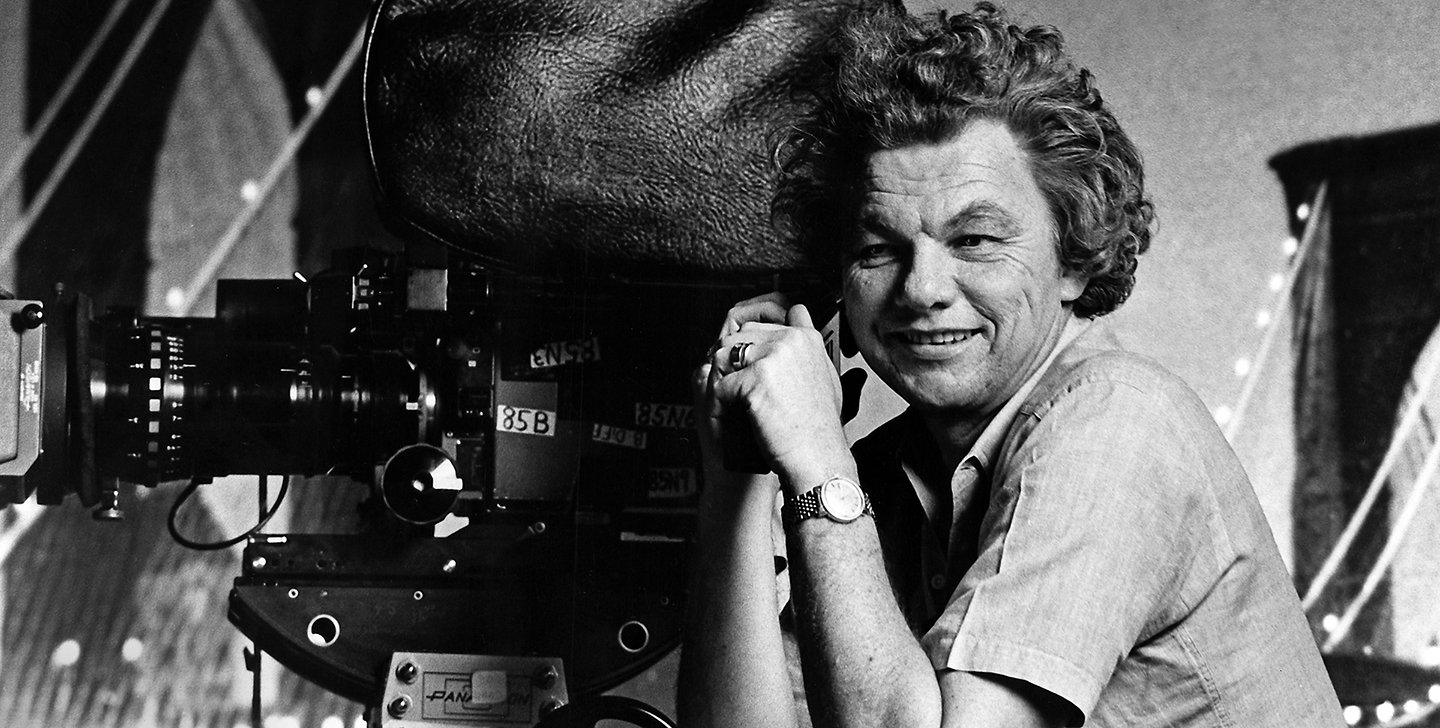

Gordon Willis, ASC: Supervising a Set

The veteran cinematographer explains his approach to workplace collaboration and managing production issues.

Photos courtesy of MGM/UA, Brian Hamill, the Margaret Herrick Library and National General Pictures.

During his long and distinguished career behind the camera, Gordon Willis, ASC has gained a reputation as a demanding and sometimes obsessive perfectionist. He readily concedes the accuracy of this characterization, noting that his exacting standards extend to his interactions with directors, actors, crewmembers and anyone else who steps onto his sets. However, he’s quick to assert that his strict methods are always intended to strengthen a picture’s narrative or aesthetic underpinnings.

As the head of the camera crew, a director of photography is not only responsible for the picture’s overall visual style, but also a dizzying array of logistical and pictorial details — ranging from the choice of equipment to the quality of the light on an actress’ face. The cinematographer must also interact with virtually everyone on a given project, from the producer to the camera loader. The resulting pressure can be enormous, and Willis understands that he can’t always be Mr. Nice Guy. Still, he insists that his occasionally stern demeanor is merely a byproduct of his professional pride. “Over the years, I have gotten upset with certain people, but only if I feel that they suffer from selective hearing,” he says.

While Willis is all too familiar with the pitfalls of motion-picture production, he still enjoys the work. “It’s a great business to be involved in when you’re on a shoot and everything is going well,” he offers. “In general, I think of myself as a low-key guy. I like making movies, and I enjoy working with other people who like it. I try to do my job well, go home and relax. At the end of the day, I like to remove myself from the process. I don’t need it 24 hours a day. Some people do, but I’m not one of them.”

Maintaining discipline on a set is a skill that comes from experience, and Willis is a keen observer of both human nature and the collaborative process. In the following pages, he offers his insights into supervising a set, including tips on hiring a solid crew, interacting with actors and directors, establishing the proper decorum, and running a tight ship.

“If I’m spending 20 minutes discussing something with a director or an actor, I don’t want a crewmember off somewhere hitting on a girl or eating a sandwich — because then he doesn’t know what’s going on, and I have to spend another 20 minutes explaining it to him.”

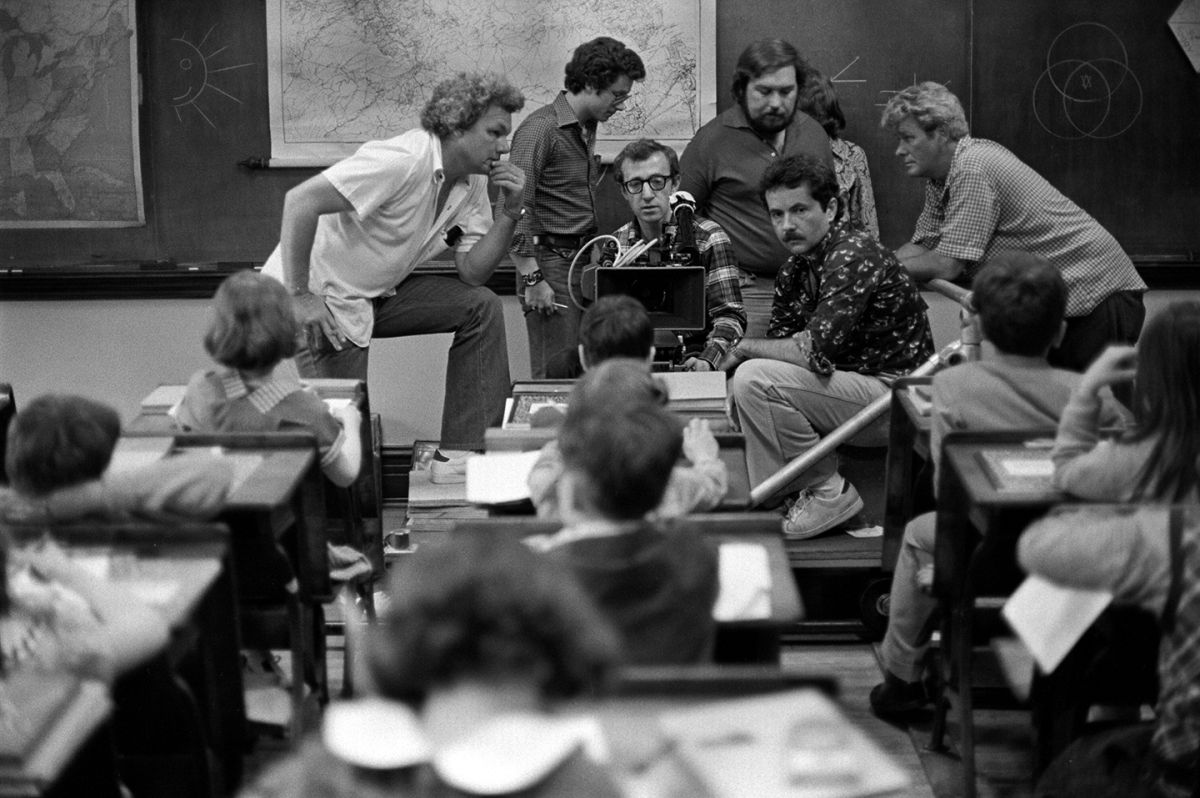

Let’s address the managerial aspects of the cinematographer’s job. As a film’s director of photography, you’re in charge of an entire crew of people. What qualities do you look for in the people you hire?

Willis: I probably look for the same qualities everyone else looks for when they hire people. I generally look for someone who’s both pleasant and technically astute. For example, if I’m hiring a camera operator, he has to be able to fulfill his primary function, but I also want that person to be able to help the assistant get everything put together properly, anticipate any problems that might arise, and so on. I don’t want a situation where he’s operating one moment and making phone calls the next. The operator has to be intelligent and able to relate well to actors. I feel most comfortable with someone who’s smart, specific and easy to deal with. It’s the same with the assistant cameraman — who, I think, has one of the most difficult jobs on the set. Another major consideration is that I want people who know how to pay attention. Everyone on the crew should be fully involved with what’s going on, because we have a responsibility to keep things moving forward. If I’m spending 20 minutes discussing something with a director or an actor, I don’t want a crewmember off somewhere hitting on a girl or eating a sandwich — because then he doesn’t know what’s going on, and I have to spend another 20 minutes explaining it to him. A crewmember should be within earshot and listening, because I don’t want to go through it all again. If you’re not listening and watching all the time, things will slip by you. A motion picture is always a work in progress, and things can change from minute to minute. You may start the day with a specific idea, but that idea can change.

Do you take recommendations on crewmembers from other directors of photography? That can potentially eliminate some of the guesswork in the selection process.

Willis: I sometimes do that, yes. If you don’t shoot with the same crew every single day, all year round, you’re eventually going to find yourself in a position where they’re not available. If you’re not working, they still have to make a living and take other jobs, and when that happens, you end up with new people. I do take recommendations from other people, and I’ve ended up okay and not okay.

How would you describe your own demeanor on the set?

Willis: My set demeanor is pretty businesslike, or maybe I should say ‘procedural’ or ‘systematic.’ I work out whatever needs to be worked out with the director and crew, and then we block things out with the actors. After that, everyone can go back to their trailers while we light. When they come back, I generally like to do a camera rehearsal and then shoot. I do prefer to work with a relaxed group of people, myself included. But I don’t like to have people dancing in the streets while I’m trying to think.

“Movies involve cooperation, togetherness and quite often compromise, but somebody has to have a grip on the steering wheel.”

When a problem arises, do you find that fear is a good motivator?

Willis: That depends. In general, I’d say no, because that type of tactic is counterproductive with good people. On the other hand, there are those who, if they sense something problematic or indecisive [in your demeanor], will try to pry your head open with a crowbar and use the moment to their advantage. It can happen with anybody, and there are certainly some movie stars who fall into that category. Movies involve cooperation, togetherness and quite often compromise, but somebody has to have a grip on the steering wheel. The thing I really like to control is noise; I think it’s debilitating, and it saps everyone’s energy. When a director and actress are working something out, everyone’s supposed to be dead quiet. Somehow, though, when they’re done and it’s time for the cinematographer to go to work, certain people take it as a license to exercise their vocal cords. When that happens, I’ll ask people to be quiet or leave. The bottom line is that my process is just as complicated as anyone else’s; the more noise there is, the less ability you have to communicate.

How specific do you get in your instructions to the crew, especially in relation to their individual functions on the set?

Willis: People function at different levels, depending on who they are and how they think. In relation to the camera operator, I’m fairly specific, and I want to get what I set up. Some cinematographers will say, ‘Okay, what’s the shot?’ and then they’ll light it while the operator works more with the director. That’s the English style of working; I don’t do it. I usually set up the shot and explain it to the operator, but I don’t want to operate after that, because I’ve got enough other things to look at while the scene is unfolding. A lot of directors of photography like to operate themselves. I personally feel that it’s too tiring, given all of the other responsibilities I have on a show. Once in a while, I’ll do a shot because I want to see how it’s working. Video’s been a help in that regard, because I can watch the shot mechanically — not photographically, but mechanically. Of course, if someone gets sick or we need another camera at the last minute, I’ll jump in and operate. My basic relationship with an operator is that I’ll talk about a given shot with the director, who usually wants a certain type of thing. Once I set up the shot, I show it to the director, who will either okay it or not okay it. If it’s not okay, we’ll make adjustments. After that, the operator gets the camera and we discuss what’s going to happen. If he’s been watching and listening, he knows what’s going to happen.

“As soon as everyone knows what’s going on, I delegate everything I can. Of course, when I ask for something specific, whether it’s a piece of equipment or a certain camera move, I want to get that; I don’t want to get almost that or something like that.”

How much responsibility do you delegate?

Willis: As soon as everyone knows what’s going on, I delegate everything I can. Of course, when I ask for something specific, whether it’s a piece of equipment or a certain camera move, I want to get that; I don’t want to get almost that or something like that. In terms of the gaffers and the grips on a show, I tell them what we’ll need, but only to a certain point. After that, it’s their responsibility to fill in the blanks and use their common sense to get things done. I don’t want people who can’t think on their own. I guess my standard rule is that you should never hire people who are dumber than you are. If you hire an idiot, it’s self-defeating — it won’t raise people’s perception of your expertise. When you get tired during a long day, you need people around you who can think. They have to be able to figure out what I’ve discussed with them; I don’t want to have to dot every ‘i’ and cross every ‘t’ for everybody. If I get stuck with people who can’t think, they won’t be around the next time.

Do you allow for much input from the crew?

Willis: Of course, that’s the only sensible way to be. If somebody sees something that doesn’t look right, I want them to tell me. I have no ego about it, or about saying yes or no. Just tell me about the problem. If I forget to say or do something, remind me; if I forget to order a piece of equipment, either tell me or have it ordered. Of course, you have to watch out for the ‘Gordon said’ syndrome, as in, ‘Gordon said we need the crane,’ or, ‘Gordon said no green cars.’

Do you often run into situations where the priorities are misplaced in terms of the budget?

Willis: Oh, sure, but that’s the nature of the business: It’s okay to approve an extra 20 feet for the star’s trailer, but if you need one more grip for a day, you can forget it! There aren’t a lot of savvy people in charge anymore, and the ones who are in charge aren’t intuitive. All they know is if they put all of these movie stars in one place, and someone takes off their clothes, ‘We’re gonna make money!’ The part where you actually have to make the movie is a passing thought to them. Motivation and intelligence are not necessarily synonymous today. The hardware you need to make the movie is always in direct conflict with someone’s comfort or someone’s bottom line. What productions spend money on, and why, has a lot to do with the ‘politics of decision-making.’ Who wants it? I’ve been in several very serious confrontations about how to shoot something and where. On two occasions, scenes that required a studio environment were being pushed onto locations by directors who should have known better. Why? Money. But in these two cases, it could not be done; it was technically and artistically impossible. Once they moved [the production] inside, the reality of why [it was impossible] soon became apparent. The cost was no longer an issue in these particular cases. No one wants to spend money on cameras, lighting and grip equipment, but honestly, I haven’t had too many problems with this kind of thing. I don’t worry about having the latest gizmos, I only care about what’s necessary. I feel that it’s not good to design shots for equipment. You should decide what you want to do, and then pick the gear. I think most of the problems I’ve had regarding budget have been confrontations about how people want to do certain things — about getting motion confused with accomplishment.

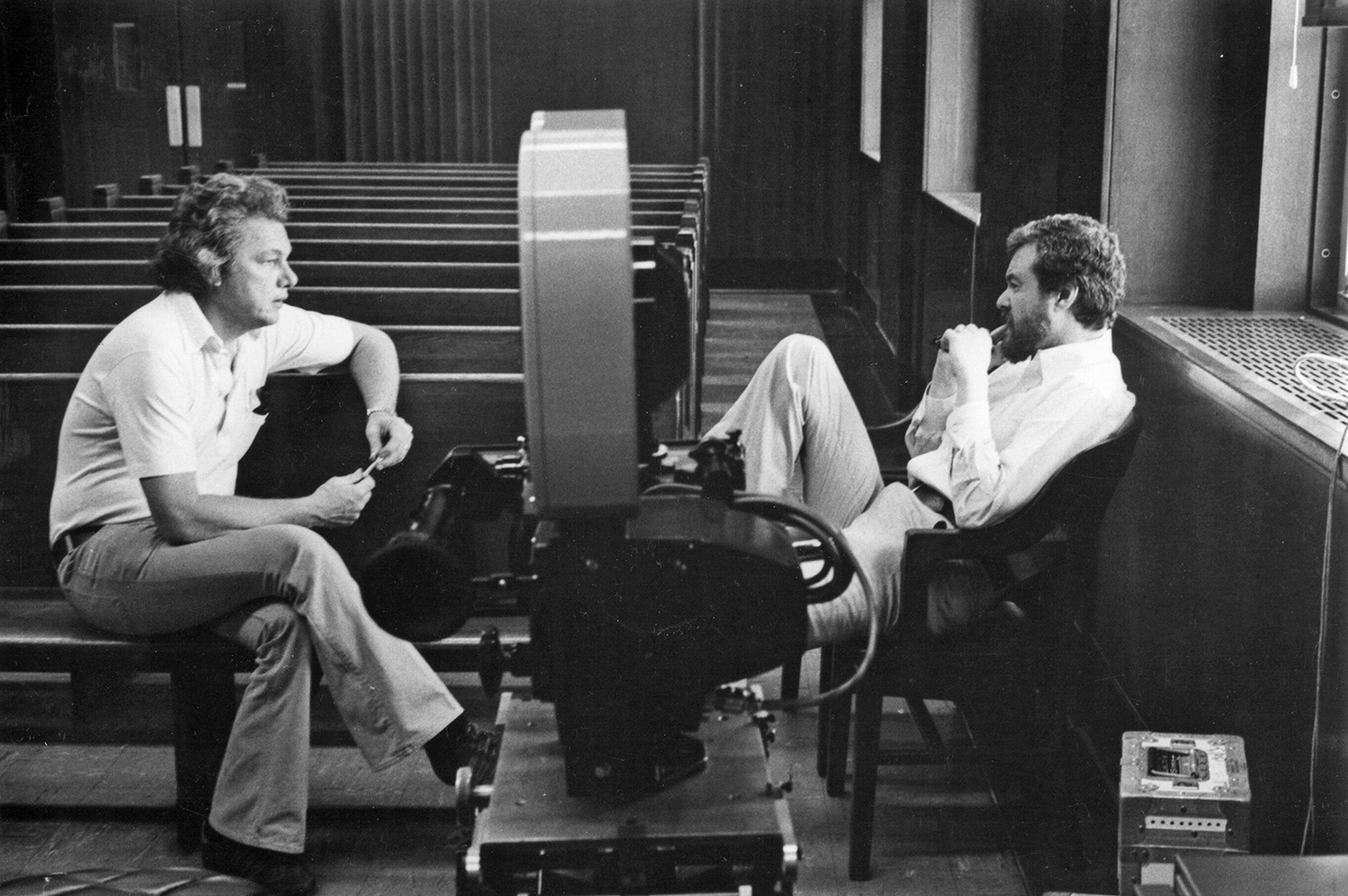

What about dealing with directors? They have their own issues, and I’m sure that the relationship can get thorny at times. Are there any general lessons you’ve learned about the ‘directorial personality’?

Willis: Just don’t forget that you’re being hired to help make their movie. Beyond that, I’ve been very fortunate. The directors I’ve worked with have all been really nice people, and they’ve always allowed me to do what I’ve wanted to do visually. I might add that what I want to do is based on what the director is trying to accomplish, but I’ve never had problems with directors telling me how to light or which lenses to use. In general, they’ve just discussed the concept and what they’re trying to achieve. Of course, one doesn’t always agree on how something should be shot — whether a scene should be close, wide, moving, et cetera. That type of discussion can be touchy. Whatever you suggest should improve or embellish the director’s design. Also, you should never express your dislike for an approach without being ready to offer an alternative that you feel can make an improvement.

I suppose part of what makes a good cameraman is the ability to step in and articulate your position in an effective, well-informed and persuasive manner.

Willis: Absolutely. When you’re opposed to something, you want to give the director a reason, and sometimes it has to make sense not only to him, but to the producers and actors as well. Sometimes you have to place things in the context of the overall priority list — ‘Let’s do this instead of that, for this reason.’ Your hope is that logic will win out if all else fails. I might say, ‘The light’s gonna be gone in 40 minutes, so why don’t we just do the last line where she says ‘no,’ okay?’

You also have to take into account the fact that a director is usually under immense pressure.

Willis: Of course. Sometimes a director is being beaten over the head by everybody — actors, producers, the studio and sometimes, I’m sorry to say, me. As a result, priorities can change. They can change for the better, or you may find yourself, along with the director, shooting junk. A director is always running in front of a moving train. Some do it well, and some don’t.

If a cinematographer is involved in a production at an early stage, a lot of those problems can be avoided.

Willis: That’s true. I don’t think directors of photography should be hired hands because the whole thing boils down to what goes through that little hole. The cinematographer has to lace it all together and present it as a moving picture, a film. There’s so much that has to be filtered through your head based on other people’s decisions. Sometimes you have to suck up a lot of slack, and deciding how long the shoot is, and where it is, can affect how much or how little slack that is. Smart producers and directors will run things by the director of photography early in the game — when the schedule’s being set up, and before the sets are built and the locations are picked. They can save an enormous amount of money that way. Half the time they don’t need what they think they need, and preparation and planning are the keys to getting a film done well. When it’s a really tight shoot and the people in charge know they have to do it in a certain amount of time, they should be very specific with the people who are actually going to do the work. No stroking, no secrets — open communication is very important. Unfortunately, most of the business is very deal-oriented. For example, the producer and/or the director may have a scene planned that will take 10 days to shoot at exterior locations, but they hire an actor who’s only available for five. ‘We can do it!’ the director yells. But shortly thereafter, he asks, ‘Can we do this in five?’ Then it rains for two days, and the actor has a penalty clause in his contract for every day he goes over the five. The suggestion may then be made to shoot the scene inside since it will cut the shooting time in half. But it’s hard to tell people that their clothes are on fire after the fact.

You directed the 1980 thriller Windows. What insights did you glean from that experience?

Willis: I learned that I shouldn’t do it [laughs]! Look, I’m a very good calibrator, and I’m very good at structure and design. I’m also good editorially as we’re shooting, and once in awhile, I do something I’m proud of visually. But honestly, I don’t have the patience or the insight to deal with actors properly. I also learned something very important about how people behave when you’ve worked with them in your former capacity; they now perceive you as a very small director as opposed to a large cinematographer. I made some very bad choices in regard to Windows, but the worst one was doing the movie! A mistake is a mistake, but I’m not sorry I did it. I learned a lot about myself and quite a few things about other people. I also found out that I have no patience for the process that directors have to go through — talking to some actress at two in the morning because she can’t figure out who the hell she is. You know, ‘What’s my character?’ Shooting the movie is easy, it’s the process that can kill you.

Does it smooth out the process if you’re working with a prestigious or powerful director who has the power to keep things in line?

Willis: It really does depend on the kind of person you’re dealing with. If the director is a politically oriented person who’s constantly trying to keep himself in place within the structure of the business, he’s not going to be strong. He’ll probably be making all kinds of compromises along the way. If an actor is running the movie, the director is going to view any suggestion or decision you make with suspicion — especially if, unknowingly, you redefine something he’s already discussed with the actor. You are now the enemy. If a director is truly in charge, you’re not the enemy — you’re an ally. If the director is strong — and I don’t mean hostile — it works better. But he has to be quite bright to deal with what I call ‘the lifeboat syndrome.’ When something isn’t working and the boat starts listing, someone in charge will occasionally think it’s a good idea to throw more sandbags in the boat to even things out — you know, ‘Let’s throw more stuff in.’ Then when that side starts listing, they want to throw more bags on the other side. And pretty soon, the whole thing sinks. When you’re having a problem, it’s usually because you’re doing too much — subtract, don’t add. It’s like the politician who says, ‘We’ve got to cut down the size of the government, and the first thing I’m going to do is form a committee to look into this.’ Now he’s added one more committee he’ll never get rid of! On a movie set, you’ll often see them hire some guy whose job is to show the actors how to hold a gun or something, and he winds up standing around for six months, ‘just in case we need him again. Besides, our leading actor, Wolfgang, thinks he makes a great meatloaf.’ You’ve got this circus train moving across the landscape, and it becomes more and more difficult for today’s director to function as he did at one time. If he’s a very strong, focused person with a lot of power, he can probably function in today’s environment.

A promising director who’s willing to stick to his artistic principles can also have an impact. When you made the first Godfather film, Francis Coppola had not yet attained that level of power, but he ‘went to the mats’ to defend his creative vision

Willis: He did, and I give him a lot of credit for that. It was not easy.

How do you deal with the actors? You have a reputation for being pretty tough with them.

Willis: Well, I don’t know where the hell that came from. All I’ve ever asked an actor to do was to repeat the blocking and do what we rehearsed. After all, it’s a movie, not a radio show. Most of the actors I’ve worked with have been very nice and very cooperative. There’s a whole school of actors who know what movies are; they know that movies are done in cuts, and they know that if it doesn’t work in the camera, then it doesn’t work. What a given actor thinks within his or her head is not necessarily what will work on the screen. Paul Newman had a great saying about that: ‘Feels good, looks bad,’ or, conversely, ‘Feels bad, looks good.’ He understood the difference between his own perception of the scene and the ‘camera reality.’ If the scene doesn’t go through that hole and onto the film in the right way, then it’s a waste of time — no matter how good the acting is. I might add that there are some actors and directors who do not grasp this concept.

How do you deal with an actor’s sensitivity about his or her appearance in a shot? After all, it’s their face that’s going to be blown up to huge proportions on a giant screen that reveals every blemish.

Willis: I do bear that in mind, and I can appreciate the position they’re in. The crew on a film has all of this gear to help them out, but actors only have one thing to rely upon — themselves. That’s what they’re selling. I give as much thought as I can to making sure that an actor or actress looks good, but I also try to make sure that they have visual support in the scene. However, you sometimes have to compromise in order to make a scene work; everyone can’t always look spectacular.

Do you have different rules or philosophies about the vanity issue?

Willis: I handle it picture by picture and shot by shot, but I’m certainly not out to assassinate anybody onscreen. I do give a lot of thought to an actor’s appearance, even though I’ve been accused of not doing so. It’s true that I don’t constantly romance everybody. Pretty women ought to look pretty if it’s appropriate for the narrative, but you have to do it without undercutting the movie. You don’t want to be doing one scene with an actress where she looks like the Virgin Mary, and then shoot the rest of her scenes like a docudrama. Then there’s the type of thing you see in some older films, where you have a gauzy shot of an actress, and then you cut to the male actor, who looks as if he’s in a completely different movie. The trick is to make everybody look the way they’re supposed to look within the given narrative. Some actresses look great in any light, and that always makes me feel good because I don’t have to take an inordinate amount of time figuring out my approach to them. I can just put the light where it’s appropriate for the scene, knowing that the person will look wonderful no matter what I do. With others, I’ll have to work things out a bit more. I’ve certainly made some mistakes over the years, but that’s part of the learning process. By the way, it’s not only the women who are concerned with the way they look. Some of the men are just as bad — probably worse.

I’m sure it’s not possible to make everyone happy.

Willis: That’s right. You can’t be all things to all men. Somewhere along the line, someone’s going to hate you!

This article was originally published in AC October 2014, and is an excerpt from the author’s forthcoming book Gordon Willis on Cinematography.