Heathers: Not Just Another Pretty Show

Cinematographer Francis Kenny takes a studied approach to doing things different for Michael Lehmann’s dark high school comedy.

This article was originally published in AC, November, 1988.

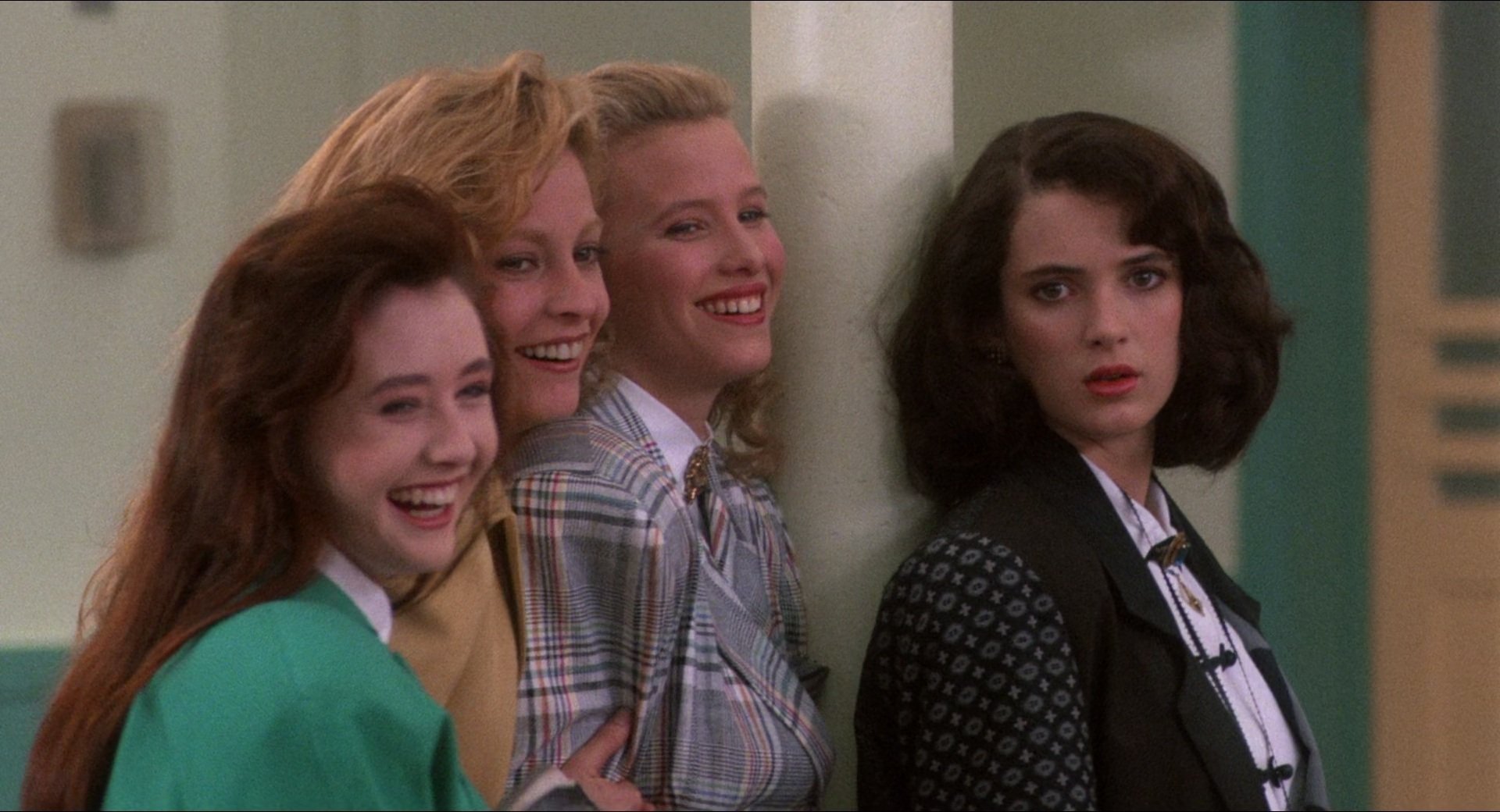

The title of the film Heathers refers to three beautiful, trendy and popular high school girls named Heather. The setting is Westerburg High, a neo-Fascist high school in fictional Sherwood, Ohio. When the new boy in school tricks his girlfriend into murdering one of the Heathers, however, and convinces the authorities that it was suicide, it becomes obvious that Heathers is not an ordinary nostalgic teen comedy flick. Murder lurks around every corner in the film, but the emphasis is on black humor, not violence. This thoroughly modern and disturbing comedy stars Winona Ryder, fresh from the success of Beetlejuice, and is accented by the imaginative cinematography of Francis Kenny.

“Heathers will probably be a controversial film, since it deals with teen suicide, and these high school kids literally get away with murder.”

Kenny has an impressive background in documentary filmmaking. His credits as director of photography include He Makes Me Feel Like Dancin’, which won a 1984 Academy Award for feature length documentary, and the forthcoming The President’s House, a historical/documentary scheduled to premiere at the 1989 presidential inauguration. Kenny has made his mark in the music video field, counting Dire Straits’ “Brothers in Arms”, Joe Jackson’s “Right and Wrong” and Cyndi Lauper’s “Girls Just Want To Have Fun” among his credits. Kenny also gained experience as a fashion photographer for Ralph Lauren and Norma Kamali.

The President’s House is a feature length film, shot in 35mm, which focuses on the White House, past and present. Kenny recalls the shoot: “It was a great honor to be chosen to photograph the White House, including the First Family’s living quarters. It’s a fascinating building, so full of history. For example, the actual handwritten Gettysburg address is in the Lincoln bedroom, supposedly along with Lincoln’s ghost. In contrast, the West wing, which houses the Oval Office and the NSC, buzzes with the excitement of being the information and decision making center of the world. You work in awe of the amount of power these people have over our lives.

“For the film, we shot some modern day scenes, and intercut them with re-creations from the past — period scenes. At times, it was difficult to photograph such a ‘white’ building in the bright and hazy days of summer in Washington. We tried to save all the exteriors for magic hour, early morning or late afternoon. In one scene, a night exterior, we recreated the storm that saved the White House after the British set it on fire during the war of 1812. We had giant wind machines, rain makers, lightning, and dozens of PA’s pulling tree branches and bushes with monofilament. After it was all over we had turned the north lawn into a swamp. While shooting at the White House, I kept thinking, ‘If you make a mistake on a feature film, they fire you. If you screw this up, who knows what they’ll do?’” he chuckles.

Back to School

Kenny recently brought his varied background to the feature film arena. Heathers is his third feature as director of photography, following Salvation and Campus Man. He discusses his reasons for moving into the feature field: “It seems all roads lead to features. It was amazing to me that shooting a film that won an Academy Award and an Emmy didn’t amount to a hill of beans in terms of having my work recognized. But if I told them that I worked on Desperately Seeking Susan or Making Mr. Right, the response would be ‘wow, you must be really good’. Unfortunately, there are very distinct divisions between the categories of work, and many people in the industry only recognize their own category, whether it be television, documentaries, music videos, or commercials. Yet, when it comes to feature filmmaking, you have to apply your experience from all of these categories, especially documentaries. There are times when too much ‘set-up’ will kill a performance. Sometimes you have to go hand-held, apply what you have learned from documentaries and just shoot it.”

Heathers takes place in and around the fictitious Westerburg High School. The school’s mascot, a Rottweiler with clenched fists, gives some indication of the tongue-in-cheek approach of the film, a departure from the nostalgic and innocent tone of many high school films. To augment the modern attitudes of the 16-year-old adults who populate Heathers, Kenny avoids any “sepia-toned remembrance images.”

“The emotional value of a scene is determined by how colors would relate to each other...”

“Early in Heathers, the lighting and camera work is very straightforward,” says Kenny. “The key lights were always done in pastels, such as Lee #152 or Lee #107. With soft tones, I tried to create a setting of a very safe world. The girls are quite beautiful, so it was easy to make them look great, and my fashion background helped. Then, as the story begins to twist into the bizarre murders and suicides, the lighting becomes more expressionistic. The hues change gradually from pastel to primary. For example, a room’s ambience would be done in Lee #181 (Congo Blue) but defined with edge light in an opposing color like pure white, or Lee #103 (Straw). The fill light decreases and the angle of the key becomes lower, creating longer shadows with very deep blacks. The emotional value of a scene is determined by how colors would relate to each other, not just by one color alone. As the darker side of the characters is revealed, the film becomes darker.

“Some of the characters — the adults — are done in brighter tones, because in the story they don’t carry much character. From the point of view of the kids, the adults have their neurotic view of the world, and they don’t understand these deep feelings and thoughts. The teachers and parents are done in 18mm close-ups. They come across almost like the Federal Express commercials, real caricature visual humor. But it's played very straight, because that's the structure of black comedy.”

Kenny allowed the movement of the actors to determine the movement of the camera, a technique he refers to as “organic movement.” Lenses were chosen according to the characters. The girls would always be shot with longer lenses like a 50mm or 85mm, and Kenny and his crew took great pains to ensure that all close-ups and their reverses were equally matched in terms of lens and distance.

“We shot with an Arriflex BL4, Zeiss high-speed lenses, and Clairmont Supa Frost filters (0 and 0 +). I really love the BL but I wish they could just make the mags quieter,” says Kenny. “We shot tests on the Tiffen Soft Cons, Low Cons, and the Mitchell diffusions, and found that the Supa Frosts were preferable for several reasons. There was very little focus loss, the blacks did not white out, and there was no stop loss. The only problem with a Supa Frost filter is that if it gets scratched, that's it. Throw it away and get another. We went through about a dozen of them. I used the new Rosco black scrim on the windows. It is a terrific product, because it cuts the light a full three stops, it doesn’t rattle in the wind like acrylic gel, it doesn’t reflect lights, and you can re-use it over and over again, which is something a production manager can relate to.”

Kenny used more than 100,000’ of Kodak’s new 5297 film stock for Heathers, and he gives it rave reviews. “I think it’s one of the the best products they’ve ever come out with,” he says. “It gives the HMI a full-bodied look that only the arc light used to give. It has extremely fine grain and a true ASA of 250. We had many interior daylight situations where the 5297 was perfect — offices, classrooms and hallways. For these scenes, I would key with something other than florescent overheads (chroma 50’s). We carried four 12K HMI’s, which would be used to key through windows. We would bounce with a corrected HMI par to fill, and usually end up shooting at around a T4. For the day exteriors, I used 5247, and for all the night work and tungsten interiors I used Fuji 8514, rating it at around 400 ASA. I really wanted to use the new Kodak 5295, but found after extensive testing that the Fuji film was of finer grain and handled the under and over exposures better. It was a little more pastel than the Kodak, but just in terms of seeing into the darkness it wins by a half stop. It also handled a three stop over exposure on windows better than Kodak. We used Deluxe for the lab and averaged around 110 total points on the printing lights.”

After a rough first day, Kenny and director Michael Lehmann were able to execute a detailed storyboard. They worked on an English system, which placed Kenny, Lehmann, and camera operator Mitch Dubin on equal terms for working out the structure of the shot, leaving Kenny to light and execute. Kenny was pleased with this setup, and feels that the strong director-operator relationship only made his job easier. He recalls the first day: “We only did nine set-ups. We were outside, shooting a croquet game, and we had to silk a huge area. We had two 20x’s and two 12x’s along with 12K’s for fill. It was very windy that day, and we tore a silk and bent a Matthews stand, bent it like a pretzel. So we were behind schedule half a day already. But the second day, things started to click, and we did 18 setups. After that, it was as if Michael had done 20 films. By the last day, we were doing close to 40 setups. On most features, if you shoot a bad scene or have a bad day, for the next couple of days, you’re gun-shy, afraid to take any chances. The point is, working with Michael and Mitch, we were never gun-shy. They were willing to give any idea a chance, and that’s very important to the success of this film.”

Death at Dawn

For the murder scenes, Kenny created excitement with unusual camera movement. There were 360-degree pans and tilts, referred to on the set as “boss” shots. Occasionally Kenny used two heads to help achieve the desired effect. In one sequence, the jocks of the school [played by Lance Fenton and Patrick Labyorteaux] are lured to a forest clearing by the promise of a romantic rendezvous, only to meet with a nasty fate. “For this shot, Veronica (Ryder) was about to pick up a gun and shoot one of the jocks,” he recalls. “We used a Sachtler fluid head on top of a Mini-Worrall geared head. We started the shot on an extreme ‘dutch tilt’ angle. When the camera began to dolly in rapidly towards the actress, the first assistant would begin to turn the Mini-Worrall head to make the horizon level. It was a very dramatic effect.

“The scenes in the woods required a dawn feeling, but in real time required several days to shoot,” Kenny continues. “For this look I used a Tiffen LLD filter. It’s very light, with a small bit of orange in it. We shot 5247, replaced the 85 filter with an LLD filter, exposed at 125 ASA, and underexposed one stop. You still get the blue look, but the fleshtones are normal. After the gunshots, the cops come in and there’s kind of a wacky chase scene. Most of this scene was shot on an ATV (all terrain vehicle) with a Steadicam. When you’re in preproduction, it’s fun to think up these wild shots (overheads and intervalometer dolly shots), but when you consider it on the set, sometimes they seem impossible. When you actually execute it, and see it in dailies, it’s a great feeling.”

Fatal Frequency

Not everything went so smoothly on the set of Heathers, however. Kenny encountered a baffling problem while shooting at the Corvallis High School [now Bridges Academy, in Studio City]. In the gymnasium, the crew had constructed a bedroom for the scene, which called for a dying girl to crash through a glass coffee table. Kenny recalls the day: “In Heather Chandler’s room, it was interior day. We pulled the roof off and double silked the entire ceiling. We went in with one big overhead block light and keyed smaller HMI’s through the windows. So there were no lights in the room, just one big ambient light on top with the key coming in through the window. In one of the scenes, our generator went to 59.61 [Hz], or somewhere in that vicinity, and we began to get a density shift over a period of 15-30 seconds, where the film actually changed exposure a whole stop. It was impossible to see with the naked eye, and the frequency meter, which was put on random lights, didn’t pick it up.

“Kodak analyzed the density of the film, frame by frame, and came up with the suggestion that I was riding aperture. We joked with the first assistant that he had accidentally connected his focus wheel to the aperture. But we got this slow wave of exposure shift — it would start getting a little brighter, and after about 15 to 30 seconds it would recede. Normally, on an HMI problem, you get a visible pulse. No one could see this until it became apparent in the high speed screening the next morning at the lab. My conclusion is that it must have been an old bulb on the large ambient HMI which couldn’t handle the frequency shift as well as the other HMI’s used in the same scene. So it turned into a major problem and we had to reshoot.”

“A good movie starts with a good script.”

Of course, working with young actors can make scheduling difficult, if not impossible. The strict requirements for education, and limitations on the number of hours a minor can work on a set, often had Kenny and the crew scrambling. One such situation arose in Griffith Park, where a master scene required lighting a cow pasture through a dense forest. This involved two 100’ condors, with two 12K’s in each, which took four hours to set up. After the crew used this huge setup for one scene, they had to lower the condors to get crew members down, set up for a reverse close-up before losing Miss Ryder to her schedule, and then relight the giant master to finish the scene. “It was absolutely insane,” laughs Kenny “If we knew we only had Winona for another 20 minutes, and we still had two shots to go, we’d go into a condition red, known on the set as ‘Winonamania.’ The entire set would explode into action in order to accomplish these shots before we lost her.”

Heathers, a New World picture, is scheduled for release in November [1988]. The film was written by Daniel Waters and produced by Denise Di Novi. “For me, it’s all about the word,” concludes Kenny. “A good movie starts with a good script. You can have the most beautiful images in the world but if the script is bad, people stop watching. Heathers will probably be a controversial film, since it deals with teen suicide, and these high school kids literally get away with murder in the story. It’s very black humor, and there are always people who will miss the point. In my opinion, though, this is a funny, interesting, and well-written film and I was very lucky to be given the opportunity to work on it.”

Kenny was invited to become a member of the ASC in 1996. His other feature credits include Campus Man, New Jack City, Coneheads, House Party 2, Wayne’s World 2, Jason’s Lyric and Scary Movie. His television work includes Justified, Greenleaf and S.W.A.T.

He was honored with the ASC Presidents Award in 2012.

For access to 100 years of American Cinematographer reporting, subscribers can visit the AC Archive. Not a subscriber? Do it today.