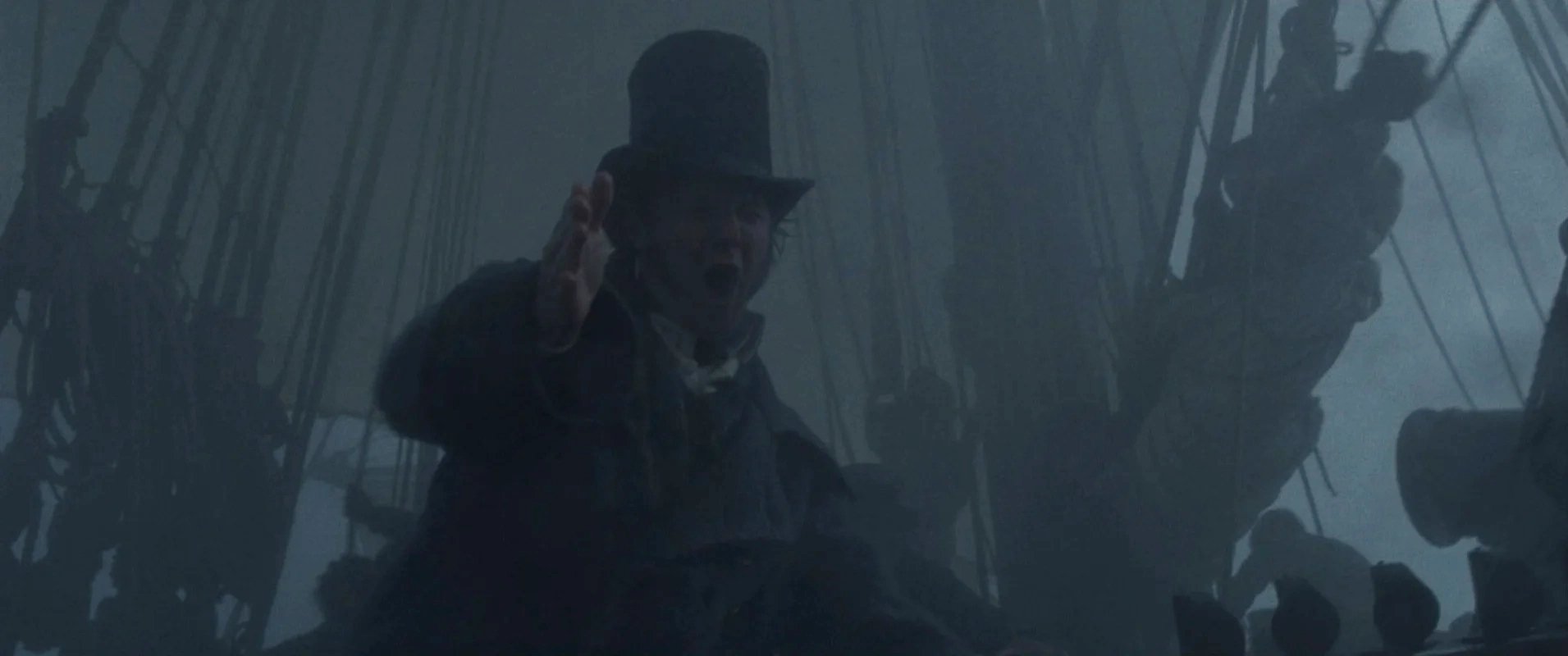

Hell or High Water – Master and Commander: The Far Side Of The World

Russell Boyd, ASC, ACS details shooting this dramatic period tale of a hot pursuit on the high seas.

A version of this story originally appeared in AC Nov. 2003.

Unit photography by Stephen Vaughan

Master and Commander: The Far Side Of The World is a rollicking high seas adventure set during the Napoleonic Wars of the early 1800s. Starring Russell Crowe as the rambunctious Capt. “Lucky” Jack Aubrey and Paul Bettany as the ship’s doctor and resident secret agent, Stephen Maturin, the film takes its name from the 10th installment in the acclaimed series of Master and Commander adventure books by Irish author Patrick O’Brien.

Combining story lines from several of the novels, the film depicts Aubrey’s dogged pursuit of the French privateer Acheron, which he intends to destroy before it can wreak havoc amongst the British whaling fleet in the Pacific. While chasing this faster and more powerful enemy, Aubrey and his crew endure all manner of ordeals, including violent storms, stilling heat and fierce battles.

Master and Commander reunites Russell Boyd, ASC, ACS with director Peter Weir, for whom the cinematographer has photographed several seminal Australian films, including Gallipoli, The Year of Living Dangerously and Picnic at Hanging Rock (which earned him the Australian Cinematographers Society’s Cinematographer of the Year Award in 1982). Boyd’s contributions to the Australian film industry were recognized in 1998, when he was inducted into the ACS Hall of Fame. His other credits include A Soldier’s Story, Mrs. Soffel (AC Dec. ‘84), Crocodile Dundee, Doctor Dolittle, Liar Liar, and American Outlaws.

“For the year preceding principal photography on Master and Commander, the only conversations I had with [director Peter Weir] were about the film... He’s always wanted to make a seafaring tale.”

— Russell Boyd, ASC, ACS

Despite not having worked with Weir for more than 20 years, Boyd describes their relationship as “very shorthand.” Says Boyd, “Peter trusts and understands the way I think about lighting and shooting certain scenes. Having spent a while apart, we’ve both gained a lot of experience and are confident in our storytelling processes. In every film he makes, Peter goes for quite different subjects. Each of his films is a departure from the others. The Truman Show, for example, was like nothing he’d done before. Master and Commander has been with him for a while, and I understand he’s always wanted to make a seafaring tale.

“The films Peter and I have worked on are always thoroughly prepped,” Boyd continues. “For the year preceding principal photography on Master and Commander, the only conversations I had with Peter were about the film, its characters, the way he wanted it to look, and so forth. There were reams of visual references, paintings, books and models. Each item had a different purpose — for example, a painting could be a reference for the look the sky should have in a certain scene.”

To create the Surprise, the British frigate upon which virtually all of the film’s action is set, a full-scale, 110’-long replica of the Rose, a real frigate that had been purchased by 20th Century Fox, was constructed in Rosarito, Mexico. Placed on a large underwater gimbal in Rosarito’s horizon water tank, which had previously been used for Titanic (AC Dec. ‘97), the Surprise set was able to rock fore to aft as well as side to side. This set was used for all shipboard exterior scenes.

“It was a great platform to shoot on, and I was able to position large lights, such as 12K HMIs, on stands on the ship’s deck,” notes Boyd.

The cinematographer’s initial concern about shooting under Mexico’s harsh summer sun was alleviated by long bouts of favorable weather. “I had thought we’d get boring, high-angle sun beating down on us every day, which would have been a nightmare to control on a three-masted tall ship,” he says.

“However, we were blessed with many cloudy, overcast days, which helped us achieve and maintain the muted period look I wanted. Under these conditions, I was also able to shoot the film’s many scripted dusk or dawn scenes for hours on end, using an 81EF filter instead of the 85 and underexposing by one or two stops, while adding a little fill light to clean up the actors’ eyes.”

“I prefer to contain the weather that is given to me...”

Boyd used Eastman EXR 200T 5293 as his exterior stock. “As an EXR stock, it’s less saturated than the Vision range, and that was key to maintaining the muted look. I rated the 93 at 160 ASA and processed it normally. For night or interior scenes, where I had more control over the contrast, I switched to [Vision 500T] 5279, which I rated at 400.”

When necessary, Boyd utilized two huge cylinders (one 16’ in diameter and the other 20’) to provide shade; he could also use them as bounce sources by covering them in Ultra Bounce material.

“While [the smaller] cylinder had been previously constructed for use on Titanic, we built the larger cylinder, which we also covered with Ultra Bounce. The larger cylinder was mounted on a construction crane that was on tracks in the tank, while the smaller cylinder was placed on a crane that was also in the water. The beauty of the cylinders was that they could be placed in virtually any position, even in amongst the rigging if necessary. My grip, Chris Centrella, spent a lot of his time on the radio, coordinating the crane drivers!”

Boyd continues, “While my basic approach for the day exteriors was to keep the actors in backlight, I prefer to contain the weather that is given to me, so I used several approaches depending on the scene. If nature provided me with a nice backlight, we simply bounced the sun off the cylinders. Sometimes I’d let the clouds provide shade, or, if it wasn’t a cloudy day, I’d use the foresails to cast shade over the actors and the 18Ks on Condors to provide backlight.

“However, backlight provides what I call ‘romantic separation,’ and it isn’t necessarily appropriate for every scene. In situations that didn’t call for that look, I’d use the cylinders for shade, lighting with a 12K Par and an 8-by-8 bounce hung pretty much over the top of the camera. When I’m lighting day exteriors, I generally keep the fill light very soft, not too directional and near the camera; that way, it acts as an eyelight as well.”

To bring out the dark tones of the wooden ship in night exteriors, Boyd utilized a combination of cross- and backlighting. “Using a backlight as the main means of separation would have thrown unwanted light onto the sails, making them look too white for a night scene,” he explains.

“I always create as full a negative [as I can] because I prefer to play around with the look in the timing, whether that’s done photochemically or digitally.”

“Instead, we placed two 18Ks on Condors and positioned them at the perimeter of the tank, crosslighting the ship on either side. We toned the lamps down by eye with singles and doubles until the ship had a pleasing look. I also used a backlight set at water level to provide a subtle rim around the hull and sails, but the crosslights did most of the work.”

Frontal light was provided by bounce from 7K Xenons or 18K Pars aimed into the aforementioned cylinders.

Boyd preferred a cool rather than overtly blue tone for his night scenes. “I tend to call my nights half-blue,” he says. “If I’m using tungsten film at night with HMIs, I’ll put half CTO front of the lamp. Certainly out in the middle of the ocean, where there is no source other than moonlight, I always tended to make the light a half-blue. On some occasions, we took dramatic license and used the bounce cylinders as a tungsten fill to replicate the light from lamps aboard the ship.

“Generally, however, lights on a ship’s deck at night are a no-no because they destroy the sailors’ night vision. For these ‘lights out’ situations, I kept everything blue and let parts of the frame fall off into blackness. The backlight was often set up to full exposure, with the front light about a stop and half underexposed.”

For scenes in which the Surprise is becalmed in the doldrums, the filmmakers shot in the middle of the day to attain what Boyd describes as a “hot, sweaty” look.

“For those scenes, I was quite happy to use a harder, somewhat unflattering frontal light,” he says. “We had to shoot them in totally windless conditions, because if the audience saw sails flapping, the scenes wouldn’t have been realistic. I let the sun do the work because I don’t believe you can effectively create artificial sunlight, at least not in wide shots. It’s my pet peeve to see something that looks lit in day exteriors. I didn’t change the exposure. I always create as full a negative [as I can] because I prefer to play around with the look in the timing, whether that’s done photochemically or digitally.”

“I light as naturally as I can. I just think it looks better.”

Master and Commander features what Boyd describes as “one hell of a storm! We went through a lot just to get that sequence looking believable. The special-effects department pumped gallons and gallons of water on us that were directed by fans and, at the height of the storm, by jet engines. When those engines were aimed straight at us, the water just obliterated everything and everyone.”

Boyd backlit the water, and he obscured the direct sunlight either with the sheer volume of water or by providing a shadow over the action with the bounce cylinders. “Given that there was so much water flying everywhere, I let most of the lighting simply happen naturally. In fact, wherever possible, I light as naturally as I can. I just think it looks better.”

The main interiors of the Surprise — the ship’s great cabin and its gun and berthing decks — were constructed in studios located at Rosarito. “Each set was pre-lit, ready to go at a moment’s notice,” Boyd recalls. “That way, if we had to go inside for one reason or another, we’d be able to go straight into shooting on any one of the stages.”

Seeking to maintain the spirit of the Master and Commander books, which depict 19th-century shipboard life with intricate realism, Boyd chose to photograph the interiors without removing ceilings.

“I preferred to work within the confined nature of the sets, so we rarely removed ceilings and walls; instead, we used the cramped conditions of the sets to our advantage. We did cheat a few times by providing light sources that weren’t necessarily there, such as the glow from lanterns or just a hint of ambient light. Mostly, we had to work hard to get lights out of shot and prevent the actors from burning up as they walked under the lights we had in those tight spaces. To achieve this, we tended to use single Kino Flo tubes taken out of their housings and flagged off with black tape.

“Realistically, I couldn't have a high level of ambient light on those sets, because there wasn’t supposed to be any light down in the decks; with the Kinos, however, I was able to light fairly specific areas in an ambient way. Every time we turned the camera around, we’d have to do a complete relight because we’d see 80 feet of the deck stretching away in the background, and we had to hide all the lights.”

Boyd explains that the location of each deck within the ship determined its look. “The farther down in the ship you go, the darker it gets, so each interior set differs in terms of contrast. That helped us differentiate those scenes from the ones that take place above decks. The gun deck was lit only through a few overhead grids and by the ‘sunlight’ coming through the open gun ports. I simulated the sun with 12K HMI Pars softened slightly with 4-by-4 frames, just to take the edge off.

“The berthing deck, on the other hand, is below the ship’s waterline, so no sun- or moonlight comes in from outside, apart from the light coming through the hatchways and down the stairwells. Production designer Bill Sandell built into his sets these great lattice grid covers for various hatches, so if there was no other light of any sort, I could always bounce some soft moonlight or send shafts of sunlight through there. Still, most of the berthing deck had to look as though it was lit by candlelight.

“I used a lot of practicals for decoration and in the background to help give the frame a sense of depth. To simulate the light from the practicals, I used warm light from a great variety of small fixtures provided by Pat Murray, my gaffer, and established a bit of ambience with quite a lot of Kino Flos hidden between the deck beams.”

Boyd credits Murray with “doing a great job, as always. Pat’s been my gaffer for a long time, and he always brings a lot to the project in terms of ideas and ways of achieving things. His array of small units and his problem-solving abilities were invaluable on these challenging sets.”

“I don’t believe audiences give a damn whether you’ve shot on a zoom or prime lens, as long as the story and performances are captured.”

The captain’s cabin, known as the great cabin, is at the ship’s stern, aft of the gun deck, and has a different look from the other sets. “This cabin has a row of windows that gave us a great opportunity to push higher levels of light into the room — we could shift from a moody, overcast look to bright sunlight or simply moonlight,” says the cinematographer. “When the windows were in the shot, however, we had bluescreen outside, so I’d just angle the light through the windows, keeping it fairly directional and out of frame.”

To keep the action flowing, the filmmakers moved the camera at all times. Using a Cartoni Dutch Head mounted on an O’Connor Head, A-camera operator Don Reddy simulated the ship's movement by constantly moving the camera from side to side. “Those type of ships didn’t rock around like a dinghy in chop,” Boyd explains. “They moved quite rhythmically fore and aft, as well as side to side, so we always kept the movements fluid rather than abrupt, even during the storm sequence. If you bang the camera around excessively, it’s easy to get the rhythm wrong.”

To gain the maximum coverage of performances while working at the cracking pace set by Weir, Boyd utilized two cameras “on nearly everything. For example, while Don was on a master angle, B-camera and Steadicam operator Harry Garvin would use a 75mm lens to pick off two or three tighter shots.

“I like to give my operator a certain amount of creative input,” he adds. “I’ve worked with Don for around 10 years, so he knows what I like. I can leave him to finesse frames at times when I need to be thinking more about the lighting. That understanding from an operator speeds up the whole process. Whenever we were off the ship on a camera barge, we used a three-axis Libra Head on a Technocrane. That combination gave us a lot of options for angles, composition and movement. On the Libra, we used the 20-100mm Cooke Panazoom, often set at the short end of the lens. We also used an 11:1 Primo.”

Master and Commander was shot in Boyd’s preferred format, Super 35mm 2.35:1. “It’s a treat for the audience,” he enthuses. “The wide frame also provides its own compositional elegance — and in this case, it certainly suited the shape of the ship.”

The film features several battle sequences, including the final, violent confrontation with the French privateer. The ships’ cannon flashes were simulated with 2K Blondes gelled with 1/2 or Full CTO that were flashed on and off into 4’ x 4’ bounce frames; generous amounts of smoke helped augment the illusion. “Blondies are great workhorse lights,” Boyd offers. “They’re tungsten lamps with a lot of output, and I like using them as bounced sources.”

The Blondes, as well as judiciously placed Kinos for ambience, were often hidden behind the large cannons and the deck-beds. To get a different style of camera movement that expressed the energetic violence of ship-to-ship combat in the 1800s, the A camera was often handheld, and the B camera was mounted on a Steadicam.

“There was a lot to shoot,” says Boyd. “Peter likes his coverage, but at the same time he’ll move fast to get it. To facilitate that approach, we used the full range of Primo prime lenses, but more often than not we were on the 11:1 Primo and 5:1 Panavised Cooke zooms. One of the cinematographer’s jobs is to get things done quickly, and zooms are a great tool in that regard; it’s just a faster way of working. Cinematographers sometimes have to realize that they’re not making films for other cinematographers.

“I don’t believe audiences give a damn whether you’ve shot on a zoom or prime lens, as long as the story and performances are captured. Master and Commander was a long and complex story to tell. One element that imbues the books with such a sense of realism is that all the characters, whether major or minor, have their own plot lines going on. Peter explored these greatly, and I think they’re the backbone of the film.”

TECHNICAL SPECS

Super 35mm 2.35:1

Panaflex Platinum, Gold II, Lightweight Panaflex, PanArri 3; Arri 435

Primo and Cooke lenses

Kodak EXR 200T 5293, Vision 500T 5279

Digital Intermediate by EFilm

Printed on Kodak Vision 2383

Boyd received an Academy Award for Best Cinematography for his work on Master and Commander and was honored with the ASC’s International Award in 2018.

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.