Heroes United — Avengers: Infinity War

Director of photography Trent Opaloch and directors Joe and Anthony Russo build on their past work in the Marvel Cinematic Universe for this franchise-spanning epic.

Director of photography Trent Opaloch and directors Joe and Anthony Russo build on their past work in the Marvel Cinematic Universe for this franchise-spanning epic.

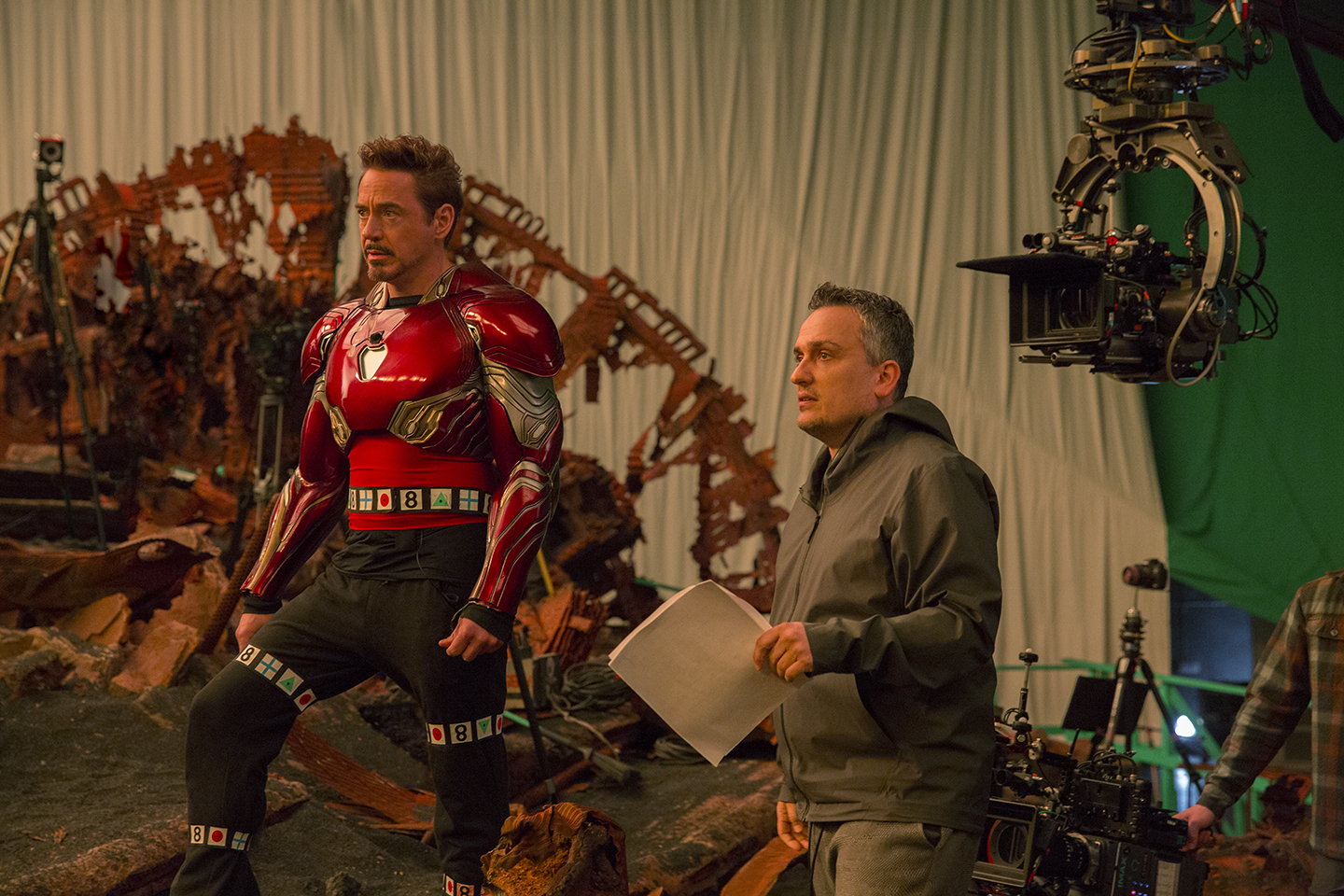

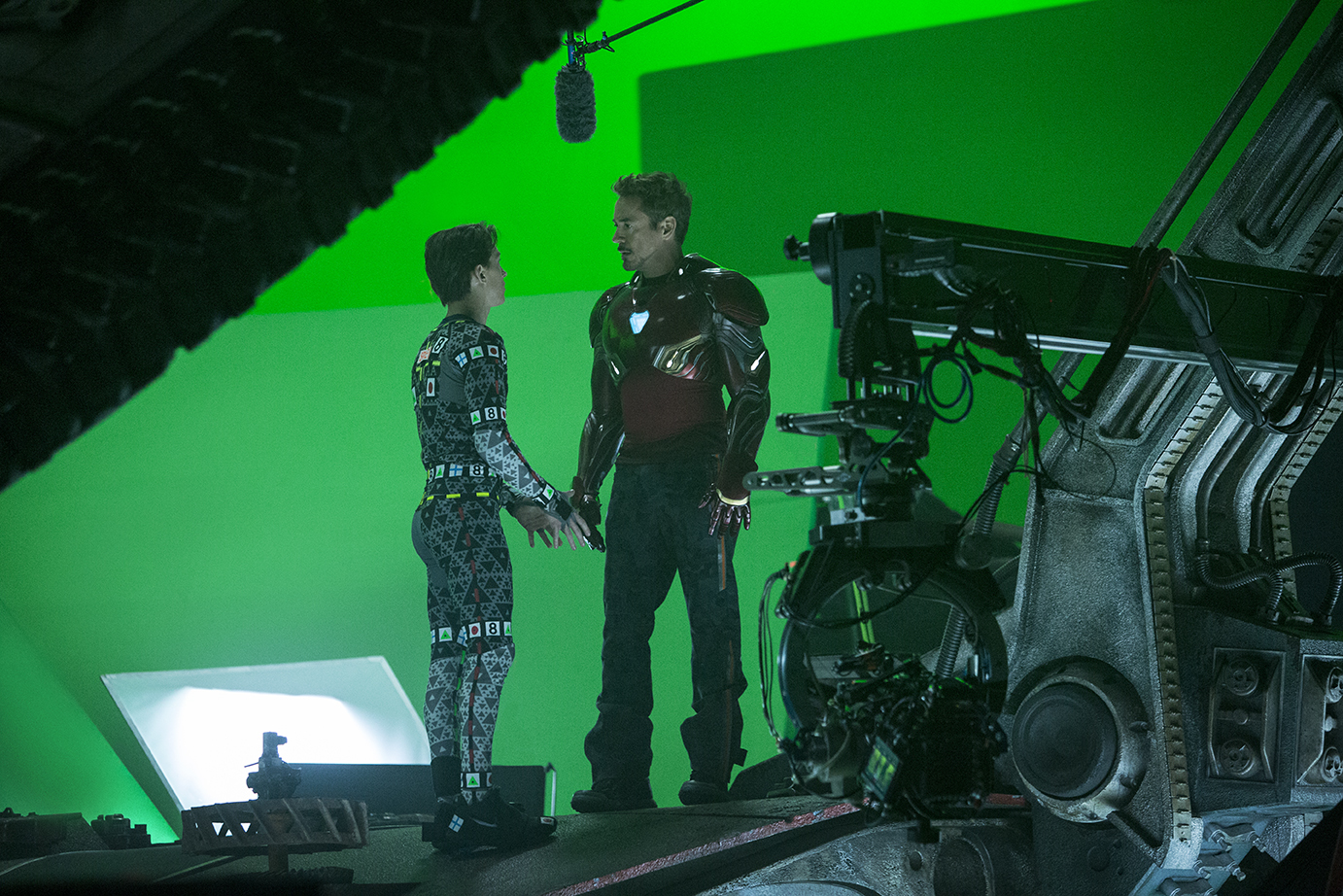

Unit photography by Chuck Zlotnick, courtesy of Marvel Studios.

Avengers: Infinity War marks the culmination of the first decade of the Marvel Cinematic Universe. The action picks up from last year’s Thor: Ragnarok (shot by Javier Aguirresarobe, ASC, AEC; AC Dec. ’17), at the end of which the realm of Asgard, home to the hero Thor (Chris Hemsworth), was destroyed. Thor and his fellow Avenger Hulk, aka Bruce Banner (Mark Ruffalo), now lead the surviving Asgardians on an exodus toward Earth aboard an Ark ship. They are intercepted, however, by the alien Thanos (Josh Brolin), who seeks the six Infinity Stones, each of which represents a fundamental aspect of the universe and provides immense power to its holder. Thanos and his Black Order generals attack the Asgardians, leading Thor’s morally ambiguous adopted brother Loki (Tom Hiddleston) to hand Thanos the Tesseract Infinity Stone.

Thor is then set adrift in space and picked up by the misfit Guardians of the Galaxy — one of whom, Gamora (Zoe Saldana), is Thanos’ estranged adopted daughter. Meanwhile, Hulk crashes down in New York City just ahead of the Black Order, whose destructive Q-Ship catches the attention of Doctor Strange (Benedict Cumberbatch) and his associate Wong (Benedict Wong), as well as Tony Stark/Iron Man (Robert Downey Jr.) and Peter Parker/Spider-Man (Tom Holland).

on the set representing Thanos’ home planet, Titan.

The Black Order has come to Earth in pursuit of two Infinity Stones, one possessed by Strange, and the other by the android Vision (Paul Bettany). Thanos intends to gather the gems in his Infinity Gauntlet, granting him the ability to destroy half the universe — which, in his warped view, would achieve perfect balance in the cosmos. And so the Avengers — who were last seen divided in Captain America: Civil War (AC June ’16) — must assemble once again, this time alongside the Guardians of the Galaxy, in a desperate bid on multiple fronts to thwart Thanos and his minions.

Directed by brothers Joe and Anthony Russo, Avengers: Infinity War is the first movie in a two-part saga that involves approximately 40 characters and transpires largely in otherworldly environments. Christopher Markus and Stephen McFeely wrote the screenplay, which was inspired by a trio of Marvel Comics series from the early 1990s: Infinity Gauntlet, Infinity War and Infinity Crusade. Speaking with AC over the phone while his brother attends an ADR session in the weeks leading up to the movie’s release, Joe Russo refers to those stories as “the greatest battle that ever occurred in the Marvel universe.”

Given the scale of the action and the number of headliners on the call sheet, speculation has run rampant regarding the combined budget for the pair of movies, the second of which [entitled Avengers: Endgame] is slated for release on May 3, 2019. [Later changed to April 26.] “They certainly are expensive,” Russo concedes. “The scale and scope is enormous and in some ways unprecedented. But beyond the effort it takes to execute something this ambitious, it’s no different than making anything else we’ve done. There are cameras pointed at actors, and it’s our job to get emotionally truthful performances out of them. There are a lot of grand-scale [visual effects], and that’s where a lot of the money goes, but it’s no different than the work we did on Captain America: The Winter Soldier and Captain America: Civil War — just exponentially greater.”

For both of those films, the Russos partnered with director of photography Trent Opaloch, who returned for Infinity War and its sequel. Civil Wars erved as a warm-up for these latest productions, as the earlier feature involved a 17-minute battle sequence, involving a dozen superheroes, that was shot with Arri’s Alexa 65 digital camera system and formatted for 1.9:1 presentation on Imax screens. The two new movies have been conceived entirely for 1.9:1 Imax presentation and have been shot with modified Alexa 65s that Imax refers to as “Imax/Arri 2D” cameras; according to a statement from Imax, the company worked with Arri to optimize the camera image for presentation on Imax’s xenon- and laser-projection systems.

“We have a lot of characters of great width and height who are well-suited to the Imax format,” Joe Russo says. “Plus there are beautiful landscapes created by [production designer] Charlie Wood that really fill the Imax frame in an unbelievable way. In my opinion, the [optimal] way to see this movie is in Imax.”

Given the magnitude of the endeavor — and the fact that the two movies would shoot back to back — the team was given a healthy six months of prep ahead of principal photography, which began on Jan. 23, 2017. The first movie wrapped July 14, and the second began rolling a couple of weeks later.

During preproduction, Opaloch recalls, “I broke down the scripts for mood and tone notes, and highlighted possible lighting gags and effects.” The cinematographer is back home in Vancouver on a long break from the second movie’s Atlanta-based shoot, which is slated to resume in September. He continues, “Before there were many set builds to look at, gaffer Jeff Murrell and I started discussing concepts for lighting rigs, and the technical and aesthetic requirements for each scene. Joe, Anthony, Charlie and I also started organizing a large collection of visual reference material from other films and still photographs, for color, framing and lighting.”

Many of the key characters have previously headlined their own movies, each of which had its own look, giving the filmmakers a foundation from which to build Infinity War’s visual language. “We had to stay true to parts of the Marvel universe,” Opaloch notes. “There’s a language to the Guardians and the characters in their world, and the same for Doctor Strange. Those previous films informed us, and we started there.”

“To fulfill the ambition of the concept, we had to bring together a lot of characters who work in different tones,” says Russo. “We went much more fantastical and colorful, especially because many locations are not set on Earth. To create that otherworldly feeling, color was important in set design and lighting.”

To help audiences follow the action across Infinity War’s myriad settings, Russo continues, “We set out with a mandate that each location had to have a color to distinguish it from the others. We didn’t want them to start blending into each other. We wanted the viewer’s brain to tune into the fact we had changed locations when the color palette changed.”

“I consider myself conservative with color and contrast,” Opaloch adds. “I tend to favor [naturalism], but with these films we had to fluff out our peacock feathers and use more of the color wheel than I normally would.” Helping in that regard, Opaloch and Murrell reteamed with lighting-console programmer Scott Barnes, a longtime Marvel veteran with whom they had worked on The Winter Soldier and Civil War. Production designer Wood — whom Opaloch calls “one of the most creative and impressive artists I’ve ever worked with” — provided further continuity from previous Marvel movies, having worked on Guardians of the Galaxy (AC Sept. ’14) and Doctor Strange, both shot by Ben Davis, BSC.

After testing, the filmmakers opted to shoot with a modified version of the Civil War show LUT. “It was changed to round out the top and bottom of the curve to make it feel a bit more filmic,” says digital-imaging technician Kyle Spicer, who evaluated footage using Sony BVM-X300 4K monitors, while the rest of the set was equipped with Sony PVM-A250 HD units.

The Alexa 65 cameras recorded 6560x3100 ArriRaw files in Open Gate mode to 2TB Codex SXR Capture Drives. The filmmakers framed for 1.9:1 with a 2.39:1 common center extraction for the non-Imax theatrical release. Zach Hilton, the on-set data-management supervisor, would collect media during reloads, using a Codex Vault XL to enter custom metadata and download the footage to 8TB SSD transfer drives, which production sent to the lab two or three times daily. Shed in Atlanta provided dailies services.

“The metadata is so important because it tracks everything from lenses to filters to defined visual-effects information for every shot,” relates Spicer. “There may be three different 50mm lenses used at the same time, and visual effects needs to know which lens goes with which camera so they can use the correct distortion map.” The metadata was also crucial in order to maintain continuity throughout an epic battle on Thanos’ home planet of Titan; the sequence was begun in the first week of production, in Pinewood Atlanta Studios’ 30,000-square-foot Stage 5, and had to be picked up again months later to accommodate actor availability.

For Opaloch, the biggest concern with shooting for the Imax format was the thought of having to abandon the anamorphic lenses he prefers. After a day of testing the Alexa 65 with spherical lenses, the cinematographer was driving through Los Angeles’ Topanga Canyon when he decided to make what he describes as a “Hail Mary” call to ASC associate Jim Roudebush, Panavision’s vice president of marketing, to inquire about the company’s Auto Panatar anamorphic lenses from the late 1950s and early 1960s.

“They have a 1.3x squeeze — not a full 2x squeeze, but enough to give it that Panavision anamorphic look I adore,” the cinematographer says. “There weren’t enough of the originals to cover all the cameras we had across different units, and as much as I love the original glass, it was a bit wild and woolly as far as flare and falloff for a movie with this amount of visual effects. So I asked if they could build modern versions.”

Roudebush had a quick chat with fellow ASC associate Dan Sasaki, Panavision’s vice president of optical engineering, and then, Opaloch continues, “They called back and told me, ‘Yes, we can do it.’ I nearly punched the roof of my rental car, I was so happy. So much of my stress was taken care of. I thought, ‘Now all we have to do is prep and shoot the movie.’” The resulting Ultra Panatar lenses — built with modern optics, mechanics and ergonomics — are a variation on the Ultra Panavision 70 lenses used on Rogue One: A Star Wars Story by Greig Fraser, ASC, ACS (AC Feb. ’17), from whom Opaloch gleaned valuable intel.

Because of the late request, the full lens selection wasn’t ready for the start of production. “We didn’t have a 35mm or a 65mm, but we didn’t mind because the stuff we were shooting looked great and made the delay in getting the rest of the ‘tweener’ focal lengths more than worth it,” Opaloch says. At the request of Swen Gillberg, one of the production’s visual-effects supervisors, the crew also employed Panavision Sphero 65 spherical lenses for plate shots.

The large format didn’t stop the filmmakers from designing intimate shots. “We do a lot of close shots for emotion and to make you feel connected with a character,” Russo explains. The show’s go-to lens was a 50mm, and for close-ups they would jump between a 75mm and 100mm. A 40mm was usually the widest lens, as the brothers felt anything wider would start to warp the frame’s linear integrity.

On their previous collaborations, Opaloch and the Russos efficiently gathered coverage with three-camera setups, but for Infinity War they often ran a single camera and designed ensemble framing. When feasible, a second camera with a different focal length would be added for dramatic scenes, and action scenes could see three to six cameras pressed into service. Geoffrey Haley was A-camera and Steadicam operator — although Steadicam was used only sparingly — and Opaloch notes, “Geoff was able to guide the storytelling through camera movement in such a way that we would get so much bang for our buck with one camera.” Kent Harvey operated B camera, with Ross Coscia on C; Harvey also served as a splinter-unit cinematographer.

Opaloch adds that lighting for a single camera presented its own challenges, as shots could cover 270 to 360 degrees, requiring the crew to follow actors with handheld Jem Balls, and to turn small LED panels on and off. “We had many more dynamic lighting cues,” he says. “We would flip our keys in shot depending on which direction we were looking. It was almost like live theater.”

The A camera most often lived on a Technocrane so it could take in the scope of the sets and characters; Infinity Warwas one of the first productions to use the SuperTechno 75. “When we required the reach of a jib arm, or if we were using a really long lens, we could go on the dolly,” Opaloch adds, “and if it needed the energy of handheld, we would do proper handheld.” For those handheld instances, Haley compensated for the Alexa 65’s weight — listed at 23.2 pounds for the camera body alone — with a combination of his Walter Klassen Steadicam vest and a bungee camera-support system that key grip Michael J. Coo built using surgical tubing.

Elsewhere, the Alexa 65 camera was placed in a Shotover K1 gyro-stabilized gimbal platform on an Airbus AS355 helicopter for location work around the hills surrounding Cove Harbour, Scotland. Helicopter Film Services’ Jeremy Braben functioned as aerial cinematographer for this and a number of drone shoots, capturing plates that would be used to create an alien terrain; Dylan Goss served as the production’s world plate-unit aerial director of photography.

Roughly 36 miles west, on Edinburgh’s Royal Mile, HFS contributed Aerigon heavy-lift drone work with Red Weapon Helium 8K S35 and Red Weapon Dragon 8K VV cameras fitted with Panavision Primo 70, Leica Summilux-C and Angenieux Optimo 15-40mm (T2.6) lenses.

Alan Perrin and Peter Ayriss piloted the drone shots, with Braben operating the drone-mounted cameras, for a scene near St. Giles’ Cathedral. Vision, who possesses the Mind Stone, is with Wanda Maximoff, aka Scarlet Witch (Elizabeth Olsen), when the Black Order finds him and a battle ensues. HFS captured plates for shots of characters bouncing off walls and smashing through windows and other architecture, as well as POVs. They shot with stunt doubles in an alleyway and at the glass-roofed Waverly train station.

To light wide establishing shots of the nighttime action in Edinburgh, 80 Arri SkyPanel S60s were rigged along several city blocks. “MBS Equipment put in place a system that allowed us to wirelessly control all the SkyPanels through one console,” Murrell says. “We had transponders so everything could ‘talk’ to everything else. We could change color over five blocks with the push of a button.”

When it came to shooting coverage, the production also positioned cranes to support three 20'x30' soft boxes, each filled with 24 SkyPanel S60s for ambient moonlight. “We came up with a nice color formula that balanced a night look with a bit of the mercury-vapor feel cities have from streetlights,” Murrell explains.

Due to scheduling, the sequence kicked off under second-unit cinematographer-director — and ASC member — Alexander Witt. Paul Hughen, ASC took the 2nd-unit cinematography reins for the second feature, but as the production schedules for the two movies overlapped, Opaloch notes, “Paul [also shot] some additional photography from the first movie.”

In an earlier segment set in New York, Tony Stark and his comrades exit Doctor Strange’s Sanctum Sanctorum to observe the carnage created by the Q-Ship. This sequence required Wood and supervising art director Ray Chan to re-create the Big Apple on four Atlanta streets. Condors with solids or diffusion frames would have been too cumbersome, so Coo and Murrell instead blocked the sun with three helium-filled 20'x20'x3' SourceMaker floating Grip Clouds, tethered at their bottom corners.

Murrell notes, “When the sun moves, you can move the Cloud to cover it, and you have a better camera angle because you’re not trying to frame out a large condor base.” Condors were used to support Arrimax 18K HMIs that could provide a backlight “sun” source from either end of the street; 18Ks were also placed on stands behind 12'x12' and 12'x20' rags for fill.

The sequence aboard the Asgardian Ark is predominantly cold blue, motivated by a nebula visible outside a giant picture window at the front of the destroyed vessel. “It’s pretty creepy,” Opaloch offers. “We wanted it to feel menacing and exposed. It’s a burning ship, with the power flickering out and fires flaring up, and it’s adrift in space. Cold, sterile light is coming into it.”

On the set, which was built in Pinewood’s Stage 6, the blue glow was created with 12'x12' video panels, each of which comprised 20 6'x7.25" Chroma-Q Color Force 72 LED battens rigged in a frame that was diffused with Light Grid and suspended on a lift. “It has the strong output of a jumbotron,” Murrell explains. “You can program video content into the Color Forces to give them movement; you can pick video content that emulates [imagery such as] a starburst, sun, fire or a star field.” These panels were put into play on a number of sets.

The rest of the Ark set was lit by 28 SkyPanel S60s configured as space lights for ambience, a dozen High End Systems SolaWash 2000 LEDs on trusses, and six Color Force 12s. Bluescreens — illuminated by Kino Flo Image 85s — were put in place to accommodate the compositing of exterior views. (In other instances, the production would use blue- or greenscreen depending on the particular scene and the characters involved.)

The epic showdown on the low-gravity Titan is marked by a twilight look, with fire-red and amber hues. “There’s a lot of destruction, and debris that gets broken up,” Opaloch says. “We’re simulating shadows from large structures floating overhead and blocking the sun.” This was done via 274 SkyPanel S60s rigged overhead to provide overall ambience for the Titan landscape. “Through the media server, Scott Barnes programmed in patterns of light fluctuations,” Murrell explains.

Opaloch adds, “There are dust clouds, almost like storm clouds that get thicker throughout the sequence. The light fluctuates and flickers. Our reference was the fires you see in Malibu, with a low sun struggling to punch through the thick atmosphere.” The crew generated smoke on the rubble-strewn set and liked how it photographed, but they used it sparingly, as it would make greenscreen separation more difficult for the visual-effects department, headed by supervisor Dan DeLeeuw. Much of the smoke, including a plume through which Thanos dramatically appears, was created digitally.

Thanos’ prior big-screen appearances were brief, and for them, the character was entirely created with CG animation. Here, though, he is so central to the story that the filmmakers wanted the verisimilitude provided by motion capture and facial performance capture. “The visual-effects team has done an amazing job bringing him to life,” Joe Russo says. “Audiences are going to forget he is not a real, living, breathing entity. Everything Thanos does in the film was performed by Josh on set.”

Finishing for Infinity War took place across five theaters on Disney’s Burbank lot. Opaloch flew from Vancouver to L.A. to review the progress alongside ASC associate and Technicolor supervising finishing artist Steven J. Scott. Senior finishing producer Michael Dillon relates that they worked with 2K anamorphic 16-bit EXR files on HP Z840 Workstations, with Nvidia Quadro P6000 GPUs running Autodesk’s Lustre 2018 software.

About the digital color grade, Scott says the directors “asked to push the blues and greens, and separate the colors so they are more distinct within the shot. It’s a fun challenge to take a slightly desaturated shot and isolate various colors to really make it sing.”

As an example, Scott references the interior of the Guardians’ ship, which was lit with multiple colors from customized RGBAW LED ribbon built into the set. An obvious approach would have been to push saturation, but instead they targeted specific colors using keyers and windows, being mindful of the wide range of skin tones, including Gamora’s greens. “We could accentuate the green light on the shadow side of her face as well as the magenta light on her other side, which is the opposite end of the color wheel,” Scott says. “And sometimes we want to introduce colors such as amber that don’t exist in the shot material. All that makes it really colorful, vibrant and bright.”

Scott, whose involvement in the Marvel Cinematic Universe stretches back to the very beginning with Iron Man(ACMay ’08), says Infinity War pays reverence to the look of earlier MCU movies. Those projects include this year’s Black Panther (shot by Rachel Morrison, ASC; AC March ’18), as Infinity War features a major battle scene set in Wakanda, homeland of King T’Challa/Black Panther (Chadwick Boseman). Scott notes, “We wanted to make sure those sequences line up with what everyone has recently seen, but this movie has a distinctly different mood. To reinforce the narrative, we start the scene with warmer hues, then progress to a cooler palette as we progress through the scene.”

The epic moviemaking journey is far from over, with additional photography on the follow-up still to come. Teasing the sequel, Opaloch offers, “Number two definitely has its own personality. We didn’t want it to feel like it was just a ‘pause and play’ on the first movie. It’s got an even more epic scope. The reference is more along the lines of David Lean.”

While the cinematographer has seen a steady rise in the scale of the movies he’s shot, he admits that Infinity War “was pretty surreal. Nearly every day I would look over at Joe or first AC Taylor Matheson and say, ‘Oh my God,’ remembering which actors would be coming in. Things like that kept us going. We were shooting for about a year, and there was always something around the corner to look forward to.”

TECHNICAL SPECS

1.9:1 and 2.39:1

Digital Capture

Arri Alexa 65;

Red Weapon Helium 8K S35,

Weapon Dragon 8K VV

Panavision Ultra Panatar,

Sphero 65, Primo 70;

CW Sonderoptic Leica Summilux-C;

Angenieux Optimo