Hiring an Inclusive Crew: It’s Our Responsibility

A call to action: “Who’s going to feel compelled to take responsibility to change things?”

Ever since my early days working out of a grip truck, I knew that when I was in a position to make decisions, it would be my responsibility to assemble crews that looked like the world we live in. I wanted to help create environments where any 12-year-old girl, no matter what color she was, or any 12-year-old boy, no matter where he came from, would be able to walk onto my stage, stand in the doorway, and see the possibility of a future.

My career began while I was in undergraduate school at Fisk University, located in Nashville, Tenn., which is one of the oldest historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs) in the country. I was taking still pictures and painting — it was a very embracing environment. While there, I met a man who would become my mentor, Carlton Moss, who was a film director, writer and historian. He wrote and starred in a picture called The Negro Soldier (1944), a follow-up to the Why We Fight series the U.S. government commissioned during World War II. It’s about Black soldiers behind enemy lines in Europe, and it has been preserved in the National Film Registry of the Library of Congress. Carlton — without saying it — was an activist. He took a look at my photographs and said, “Whoa. You’ve got the eye of a cinematographer.”

I had never heard that word before. I didn’t even know what a cinematographer was.

A filmmaker named Ousmane Sembène — the father of African cinema — came to Fisk to screen two pictures he’d made, Black Girl and Mandabi (the latter based on his novel The Money-Order). Carlton brought him by my little 50-dollar-a-month apartment, and through a translator, Ousmane said the same thing Carlton had when he saw my paintings and photography. Before I knew it, Carlton was sending me a subscription to American Cinematographer, and shortly after that, he sent me a 16mm Arriflex S with a 400' magazine, some film, and written instructions on how to load the camera. The camera came from Roz and Cal Bernstein, who owned a production company called Dove Films.

“At USC, I was the only Black kid in the department. It was interesting considering I grew up on the South Side of Chicago — one of the most segregated cities in the country.”

After I graduated, with Carlton’s help I received a scholarship to USC’s film school; my application included a presentation of my work that I had done with him, and with the little 16mm camera. At USC, I was the only Black kid in the department. It was interesting considering I grew up on the South Side of Chicago — one of the most segregated cities in the country. I was around Black people all my life, and Nashville was just as segregated. So when I got to USC, it was a bit of a culture shock because it was a different experience doing my work and being the outsider.

Carlton also got me a job at Dove Films, where Vilmos Zsigmond, ASC, HSC was the resident cinematographer. It was 1976, and the finest cinematographers in the world shot commercials there: Haskell Wexler, ASC; Vittorio Storaro, ASC, AIC; Sven Nykvist, ASC; László Kovács, ASC, HSC; Jordan Cronenweth, ASC. Everybody that anyone could admire was a cinematographer for Cal and Roz.

On my first day of work, I walk onto the grip truck, no one is there, and I look at the grip box. It was covered with the most derogatory jokes and cartoons — about Martin Luther King Jr., César Chávez, Asian people from the Vietnam War — just horrible, derogatory humor. This was very different from Cal and Roz, who wouldn’t even have grapes on the craft-services table because the United Farm Workers had gone on strike. When Styrofoam cups were found to be environmentally impactful, there were no more Styrofoam cups on the set. In the 1960s, Cal and Roz also hid Carlton in their home during the House Un-American Activities Committee investigations, when everybody was being subpoenaed because of their leftist views. Carlton got subpoenaed during that period, along with so many other artists and writers whose lives were destroyed, and they let Carlton and his wife live in their attic while they prepared their case.

So having this grip truck in front of their production company — with all these derogatory things inside of it — was obviously something they didn’t know about.

I left that truck, went into the office, and called Carlton. I said, “I think you’ve made a mistake. Here’s what I just saw.” And he said to me, “Simmons, do you know any Black people making movies?” I said, “Nope.” He said, “You like cinematography, right?” I said, “Yeah, I like it a lot. I love it.” He said, “You want to be a cinematographer?” I said, “Yes.”

And he hung up the phone.

I worked with those people on that grip truck for a couple years, and it was a very challenging environment. I didn’t let it stop me — I just stayed. Because, like I tell all young people who come to me, if there’s something that is a second choice to being a cinematographer — or any kind of artist at all — you should go for the second choice. Because the first choice presents obstacles, and the passion has to be greater than the obstacles.

And that’s what I would tell myself. I saw that at the end of that road I would be able to do something that I really wanted to do. I could be a cinematographer.

During my time on the grip truck, there was a man named Jerry Posner, who never participated in the rest of the crew’s humor, which consisted of one N-word joke after another, preceded by, “Hey, Johnny, you know this isn’t about you — but I’ve got to tell this joke. You don’t have to listen to it.” But there would be nowhere to go. We’d be on the road, in another town someplace, and I would be listening to this crap. Posner would be in the back of the grip truck, never participating — he would just observe. Then one day, 20 years later, I’m at Warner Bros. Studios pulling into my parking space early in the morning, where it says on the side of the building, “John Simmons, director of photography.” And there’s Jerry Posner. He walks up to me and says, “I knew you’d be OK, because you stayed there. And now look at you. I don’t know how you did, but you stayed. When they would say, ‘Don’t bother me right now,’ when you asked a question, you would come back and ask the question later. And I knew that one day, I would see you and you would be OK.”

“There were times during that period in the early ’90s when I would go onto a set, and I’d be checking out a stage, and a white security guard would walk in and ask me what I was doing there. And it would be my stage. I would have to say, ‘I’m John Simmons, director of photography.’”

Working on that grip truck was how I started in this business. And at the time I would also do PA jobs, and when I would drive onto the lots to deliver something, often it would be like being in the Deep South somewhere. I wouldn’t see one person of color on those lots. And when I did see a person of color — a security guard or another truck driver — they would be a block away, and we would wave to each other like, “Hey, man, I’m over here, too.”

Because I came up through the civil rights era, I knew that during that period when I had to work with those people and put up with all the things that they presented to me — and they presented a lot — that they represented more than a film crew. They represented a picture of America. They represented something that had shaped the way people see us — and by “us,” I mean “me.”

There were times during that period in the early ’90s when I would go onto a set, and I’d be checking out a stage, and a white security guard would walk in and ask me what I was doing there. And it would be my stage. I would have to say, “I’m John Simmons, director of photography.” They would say, “Oh, okay. Just checking,” as if they were going to ask the same thing of anybody that was standing there. But I have obviously been Black a long time, so I know what that kind of greeting is like: assume first, ask questions later. And it stayed that way for a long time. I’m not sure it wouldn’t still be that way now, except my hair has turned gray. So now when I walk onto a set, people aren’t looking at me like I’m about to steal something.

The first time I did get into a position where I was able to make some decisions about my crew, I was shooting a documentary for Carlton. It was called Portraits in Black: Two Centuries of Black American Art, to accompany an exhibit at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. It was a very small crew. My two hires were Black people, and Carlton was teaching at Irvine University and had some students there that he wanted to give exposure to — and just as I’d envisioned, our crew looked like the world we live in.

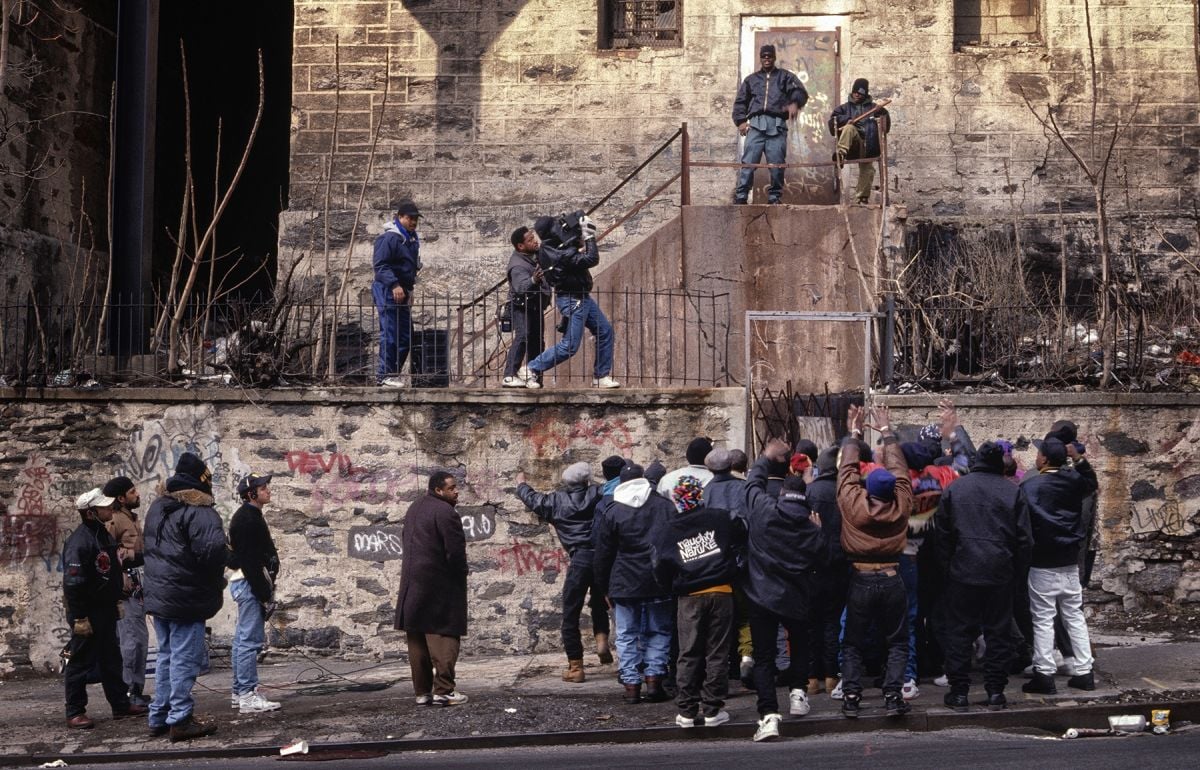

I then started shooting music videos for artists like Stevie Wonder, the Whispers, Snoop Dog, Dr. Dre, Tupac, Naughty by Nature, Jessica Simpson and Fishbone, among others. For those crews, I made it a point to have a diverse mix of people. It wasn’t by accident — I would seek these people out.

After the music videos, I started working for a company called the Film Syndicate, owned by Bryan Johnson. We did network promos and commercials. Bryan also liked the idea of our crew looking like the world we live in, so I hired women and other people from underrepresented backgrounds as assistants and operators. I made sure that everybody I could possibly represent would be there — that’s always been a responsibility for me.

When I did my first multi-camera show, the studio assigned me a gaffer and a key grip because they had prior experience. My gaffer was a white guy — whom I still work with — and I told him my views on hiring. But, ultimately, people hire who they know. So he came to my show with only white guys, and I had to tell him that we could do the pilot like that, but we couldn’t do the series like that. And it was a drag in a sense, because we spent a few weeks together with the guys he brought to the set, I liked them, and we had a good time. There was no reason why I couldn’t continue to work with them — except that the crew was imbalanced. I had feelings about them not being able to come with me onto the series, but more important than that was my decision to diversify my crew, and making a difference in this industry.

“There can be all of the studio mandates for inclusivity in the world, but the only way to change the industry is for every person to take complete responsibility for it.”

However, even being in the position to make hiring decisions didn’t make things any easier or more equal. I was doing a commercial on a huge set, and I didn’t have my regular crew to rig because we had just finished shooting something all night the night before. I was on set, working with some rigging crew, and the camera was in the corner because we were going to shoot a test that day. The camera assistant had put it together, covered it and left. So I uncovered it and was looking through the viewfinder — and a man, up in the perms, says to me: “Hey, buddy. Leave that alone.” I didn’t say anything. He said it about two or three times, and he finally crawled down a ladder and said to me, “I’m sure Mr. Simmons would not want to see you playing with that camera.” I said, “You know Mr. Simmons?” He said he did, so I said, “Well, it must be a different one, because I’m Mr. Simmons.”

Another time, I was making this picture called Once Upon a Time … When We Were Colored down in North Carolina. It was a Black story with many Black actors. The crew was pretty balanced, like it should be. My department heads were people of color. My focus puller was Michelle Crenshaw, who is now a camera operator and cinematographer. One day on set, we were filming a scene that involved a Klan march. Since I had something like five cameras shooting that day, I had to operate one of the cameras. I was sitting on my camera, and someone says to me, “Hey, man, don’t play with that — get off that camera.” It felt like my past all over again.

Those are just two examples. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve been asked not to mess with the camera when I’m in charge — or be questioned about why I was on the stage by myself.

There can be all of the studio mandates for inclusivity in the world, but the only way to change the industry is for every person to take complete responsibility for it.

The main thing about the movie and TV business is expedience. You never have enough time to get something done. You’re always behind the clock. Because of that, you establish a crew, and a crew is like your family. So, if I’m talking to a guy who has never had any Black people working for him, and all he’s had with him are the people he knows, and those people work well together — they have all the shortcuts down, they know all the language, all the abbreviations, everything that makes things happen quickly with the least amount of conversation — the last thing they want to do is disturb that family. And they also know they are supporting people’s lives. I understand that. But it’s also perpetuating the lack of inclusion.

“The problem with the business — and one reason why there is a small number of Black people in the ASC — is that we don’t have the opportunity to gather the body of work that allows us to present it, to be equal in that way to the other members in the ASC.”

Change can begin with the cinematographer, because we are in charge of the crew, and the gaffer and the key grip also have to get on board. This is not for diversity, but for inclusion. To change the industry and fix the current imbalance, cinematographers have to be concerned about changing the world, evening out the balance, making this place accessible to everyone, and providing dreams and opportunities for people. And that means that somebody on that crew is going to have to go someplace else. Cinematographers are going to have to open the door and let someone new in. It might not be easy for people to do that, but it’s necessary. And when they do it, perhaps they will be criticized for it, and I’m sure it will be a big decision — but it’s what I do, and I’m asking you to join me.

The ASC is a product of the industry — it’s not the industry. When a cinematographer is considered for ASC membership, they are judged by members on their body of work. It’s only at the interview with the candidate that you actually get to see the person and you know whether they are Black, white, Chinese, et cetera. After that interview, the candidate’s work goes out to the entire membership body, and they just become another cinematographer. The problem with the business — and one reason why there is a small number of Black people in the ASC — is that we don’t have the opportunity to gather the body of work that allows us to present it, to be equal in that way to the other members in the ASC.

I’ve taught cinematography at UCLA for 26 years, and every one of those classes was about inclusivity, simply by virtue of the people who attended; it has always been a diverse group. Working with 28 people per year for 26 years, the numbers add up — and I’ve also mentored many of them long after they’ve left the classroom, which I consider a very important thing to do. Some of these filmmakers have become quite successful in the field, and even become ASC members themselves — but I know first-hand from seeing their work that there are a lot of brilliant cinematographers whose only obstacle to success is this lack of opportunity.

The Black cinematographers who are now ASC members have been fortunate to gain a body of work. When director Tim Reid hired me to shoot Once Upon A Time … When We Were Colored, which was a big feature film for me, it opened a lot of doors. When French director Euzhan Palcy made The Killing Yard at Paramount, she insisted on a Black cinematographer, so I was able to gather work. Bryan Johnson at the Film Syndicate gave me commercials. So I was able to present a body of work, which had a lot to do with destiny, luck, and the way I’ve conducted my career, no doubt.

“As people make these decisions to bring people of color onto the set, it has to be clear that it’s an inclusive situation — that we’re not just trying to create statistics. It has to be that we’re actually trying to make a difference.”

My career has been built upon people who backed me as I was coming along, who wanted me to be successful — Lenny Hollander at F&B Ceco, ASC associate Robert Keslow of Keslow Camera, director Debbie Allen, and director Spike Lee, to name a few. I stand on the shoulders of so many people who trusted me, and gave me opportunities and equipment, and shared their knowledge.

I got into the Local 600 union because of a woman named Shirley Moore, who had an organization called ABET — Alliance of Black Entertainment Technicians. She called me up one day and said, “Johnny, the union door is open. You need to get over there, show them your days and check stubs, and let them know that it’s time to go to work.”

Confronting this problem of lack of diversity, the people who have benefited most from the efforts are white women. Right now, many positions in the industry have been filled by women, but people of color are still being left behind. And while it’s wonderful that women are getting more opportunities, it needs to be acknowledged that much of that change has taken place because of the efforts of Black people and other people of color — and things are changing very slowly for us.

Even cinematographers from countries outside of the U.S. — from locations such as Europe, Latin America and Asia, for example — were typically able to hone their skills in an environment where they were not minorities. They weren’t being looked at as someone who was intruding on an established system. Right now, a lot of white women are being hired, rather than women of color, and that is likely because that is more “comfortable” to some people. They are hiring people they are accustomed to being around and seeing. When people step forward and hire us, it’s a big deal. But that’s not to say that it wasn’t a struggle for those women to get to work, either, because many men were not quick to prioritize gender parity in hiring. I’ve always prioritized hiring women of color on my crew, even back in my music-video days when misogyny in rap lyrics may have been uncomfortable.

Activist Vernā Myers has said that diversity is being asked to come to the party, and inclusion is being asked to dance. As people make these decisions to bring people of color onto the set, it has to be clear that it’s an inclusive situation — that we’re not just trying to create statistics. It has to be that we’re actually trying to make a difference. Because nobody wants to work in an environment where they aren’t welcome, and their contributions aren’t important.

When Cynthia Pusheck, ASC and I founded the ASC Vision Committee with then-ASC President Richard Crudo in 2016 — and when that committee spawned the Society’s mentorship and scholarship programs — our purpose was to help underrepresented cinematographers reach their goals. An important part of that process continues to be raising the awareness of people in decision-making positions — not only of what needs to be done, but why these decisions are essential to the progress of our craft. And with that knowledge comes responsibility.

There are cinematographers who have fully made a choice to create change, like Alan Caso, ASC. When he was honored in 2018 with the ASC Career Achievement in Television Award, he spoke bluntly and honestly about the advantage of his white privilege, and everybody listened to him. He got a standing ovation. He was honest with his position in the business, and he changed his crew. He hired women and men of color — he was very inclusive in his hiring.

As we move forward, the question becomes: Who’s going to feel bad about their previous hiring practices and lack of inclusivity, and use that feeling to make a tangible change? Who’s going to feel compelled to take responsibility to change things? The answer will determine whether the wall of faces at the ASC Clubhouse stays what it has been for the past 100 years, or if it becomes a portrait of the faces that represent the world we live in — a place where that 12-year-old girl or boy, now grown up and creating images of their own, can see their face, too.

I ask — what will the filmmaking and cinematography profession look like 100 years from now? Maybe it’s time to get it right.

One person can make a difference. Be that person.

About the Author

John Simmons, ASC grew up in Chicago and has had a prolific career as both a still photographer and cinematographer. He has collaborated with filmmakers including Spike Lee and Debbie Allen, and has photographed more than 25 television series, including Roseanne (2018), Family Reunion, No Good Nick, Prince of Peoria, Men at Work, Good Luck Charlie, Dog With a Blog, All of Us, The Tracy Morgan Show, and many others. Simmons earned an Emmy for his work on Nicky, Ricky, Dicky & Dawn, another two nominations for his work on Pair of Kings, and a third for Family Reunion. His feature credits include Once Upon a Time … When We Were Colored, The Killing Yard, Collected Stories, The Gin Game, Asunder, The Old Settler and the documentaries Cool Women and Dark Girls. His photographs are held in the collections of the Harvard Art Museums; the High Museum of Art; the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; the Center for Creative Photography; and the David C. Driskell Center, University of Maryland. He serves as a vice president of the ASC and on the Board of Governors of the Television Academy. He is the co-founder and co-chair of the ASC Vision Committee.