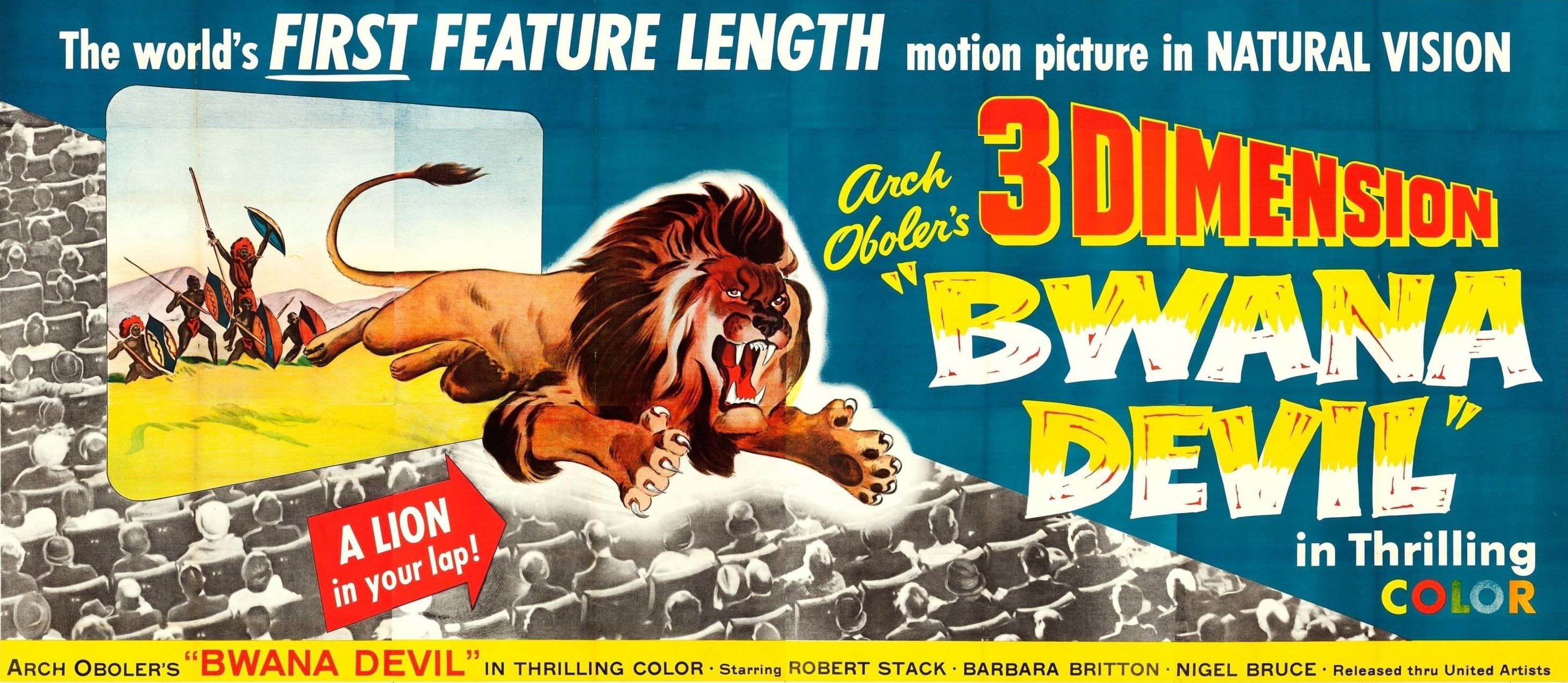

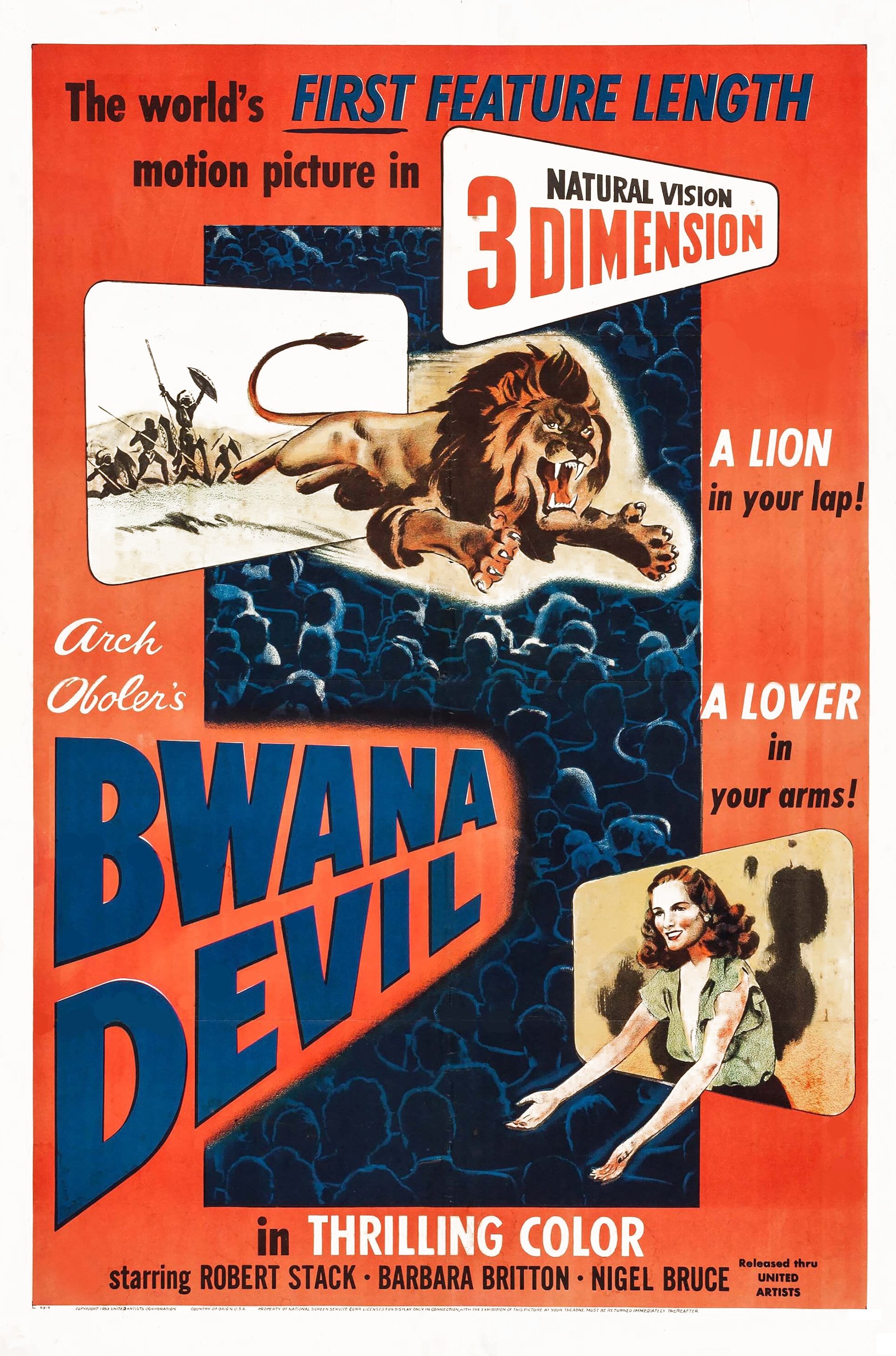

Hollywood Launches 3-D Film Production: Bwana Devil

Industry's first feature-length 3-dimensional motion picture filmed with Natural Vision Corporation's new stereoscopic cameras.

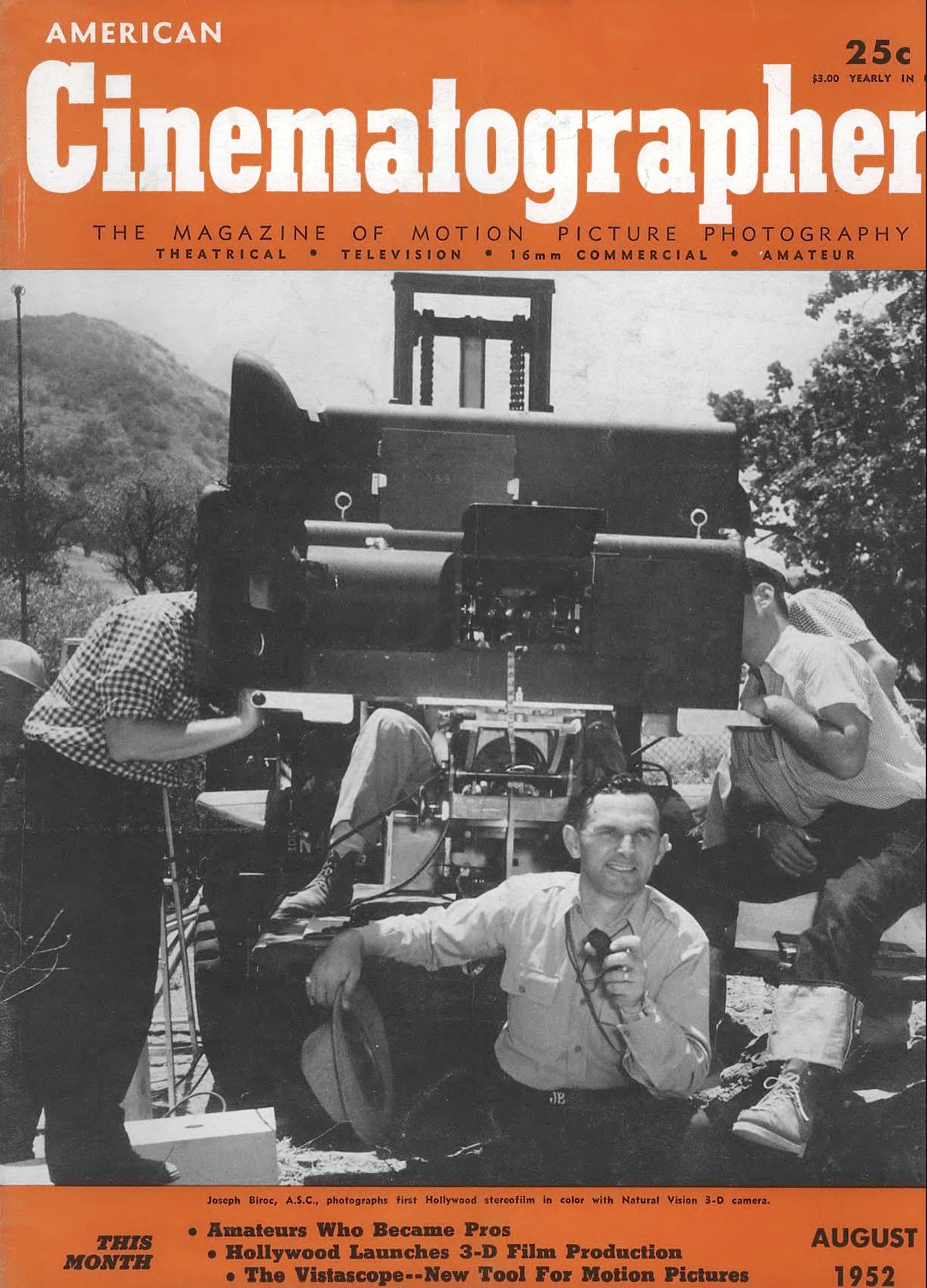

By Joseph Biroc, ASC

Three-Dimensional movies have been the subject of increasing study in the United States and Europe for the past 25 years. The U.S. Air Force already is using stereofilms for training purposes, marking, perhaps, the most substantial use of practical 3-D movies anywhere. At the present time, three different stereo systems are being developed in this country, but the top contender, by virtue of its recent successful test in Air Force and feature film production, is that of Natural Vision Corporation of Hollywood.

Bwana Devil, the first feature-length 3-dimensional color film in history, went before Natural Vision’s 3-D cameras on June 18. Produced and directed by Arch Oboler, the picture has an African locale and stars Robert Stack, Barbara Britton and Nigel Bruce.

Natural Vision is said to be the first 3-D system yet developed which is based on the fundamentals of natural vision, hence its name. The 3-D camera is actually two cameras in a single unit photographing separate film strips. These in turn are projected simultaneously with two projectors interlocked to run in unison. While other 3-D systems have employed dual cameras, none have pursued the theory that the 3-D cameras should see and record the scene exactly as the human eyes see it. In other words, twin cameras placed side by side and focusing directly on the scene overlook the important factor of parallax. Natural Vision’s system has variable parallax as the crux of its system. The result is 3-dimension pictures on the screen that induce no eye strain. Polaroid spectacles are worn by the audience in viewing the pictures, the same as for other 3-D systems.

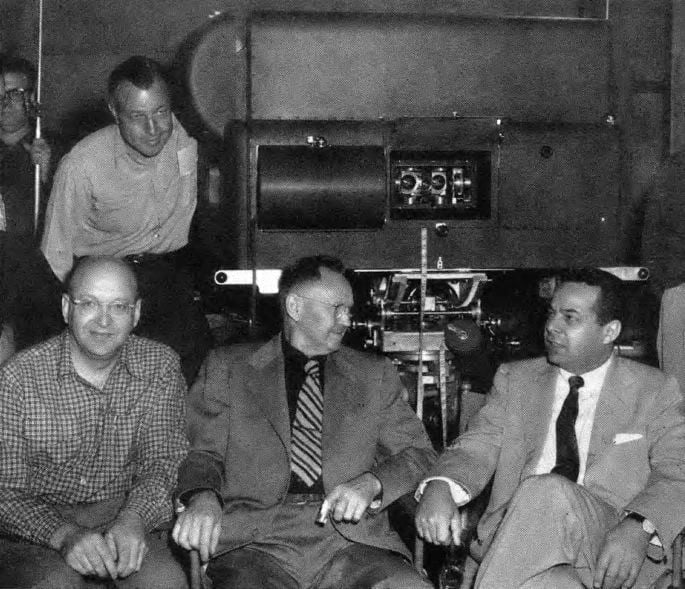

Credit for engineering the Natural Vision camera equipment goes to Friend Baker, a pioneer in the 3-D field for over 23 years, and camera technician 0.S.“Bud” Bryhn. Until recently, Baker’s developments have been in the field of 16mm 3-D movies. It was a chance meeting between Baker and Milton Gunzburg which led to developing the 35mm 3-D cameras.

Gunzburg had undertaken to produce a documentary film about a youth and a hot rod. When the conventional motion-picture camera attempted to record the innards beneath the hood of a hot rod, the pictorial result was disappointing. Someone suggested it would be better if filmed in 3-D. Gunzburg looked around for someone who could supply such equipment, and his search led to Baker’s workshop at Motion Picture Center studios in Hollywood. To shorten the story, the 3-D camera used by Oboler in filming Bwana Devil took shape in record time. Into the picture, meantime, came also camera operator Lothrop Worth, who, together with myself, photographed the initial tests with the equipment. The camera was tested periodically for about six months, and when it was declared perfect, Gunzburg looked around for a producer to make a picture.

The tests which I photographed were screened before members of the American Society of Cinematographers at their Clubhouse early this year. Other screenings followed; then one day Arch Oboler heard about them. He was in the midst of preparing a new production — a rugged tale about pushing a railroad through an African jungle. Always one to explore the merits of any new cinematic innovation, Oboler looked at the Natural Vision tests and decided to shoot Bwana Devil in 3-dimension, using Ansco Color. Because of my experience with the camera in making the extensive tests, I was engaged as director of photography on the picture. Worth and Bryhn, operator and 3-D technician respectively, and Howard Schwartz and Gene Hirsch as assistants made up our camera crew.

The Natural Vision camera is an interesting piece of equipment. The accompanying photos show the camera in its blimp, and the unique technical details are therefore not visible;

record through precision parallax-corrected optics on two separate films, supplying left and

right images. Cameraman Joseph Biroc (right) views scene through one of dual cameras while

operator Lothrop Worth (left) observes it through central viewfinder. Simultaneous viewing

of scene is afforded by second camera, also.

Inside the blimp are two standard Mitchell 35mm cameras mounted on a base plate with the lens turrets facing each other. In between are two front-surface mirrors having micrometer adjustments, which reflect the scene into the camera lenses. Controls at either side of the camera base lead to the swivel-mounts holding the mirrors, and enable making the fine micrometer adjustments for the highly important parallax correction prior to shooting each scene. Thus, the two cameras record the scene in left and right images, properly related with respect for parallax.

In addition to moving the mirrors, there is provision for changing the viewing angle of one of the cameras. Mounted on a rotating base, this camera may be pointed at a slight angle in conjunction with the mirror adjustments to achieve the correct parallax.

The usual complement of four lenses is missing from the cameras’ turrets. Only one lens is mounted on each camera, and this is changed as the need demands The various pairs (paired for equivalent focal length) of lenses used are carefully matched and tested.

Despite the apparent bulk of the camera and the need for critical adjustment of the optical equipment prior to recording each take, it is possible to attain remarkable speed in making new setups. This is due mainly to the facilities provided by the two cameras and viewfinder which permit the cameraman, operator and the director to scan a scene during a single rehearsal, all at the same time. This eliminates the need for separate “run-throughs” for each man, as when shooting with a two-dimension motion picture camera.

men involved in its development: Seated (from left) are Dr. Julian Gunzburg, eye specialist and

technical director; Friend Baker, designer and engineer; and Milton Gunzburg, president of

Natural Vision Corp. Operator Lothrop Worth stands next to camera.

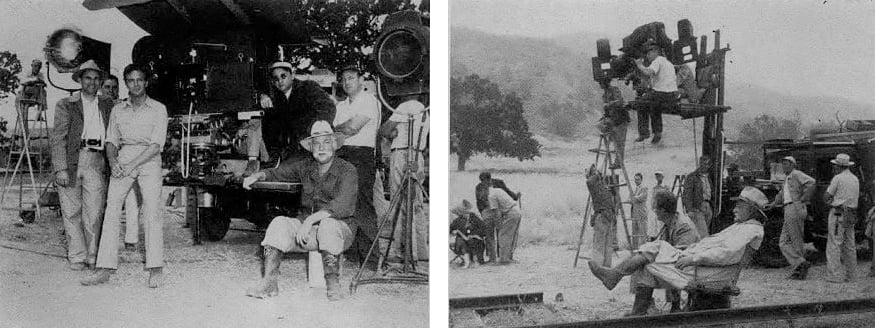

Selecting camera setups calls for the careful placing of people and dressing of sets, together with the careful selection of lenses of correct focal length to avoid false perspective and distortion. To keep things rolling on the Bwana Devil production, most of these decisions were made by Lothrop Worth and myself. Only when we encountered very complex problems or situations in attempting an extreme effect called for in the script was it necessary to talk it over with Mr. Oboler. In such instances, the many tests we made previous to production served as an excellent yardstick.

The operating crew working with Natural Vision cameras must be exacting in their work — much more precise than in 2-dimension cinematography. The mirrors, which are the critical center of the system, must be carefully positioned and checked, both before and after making each shot. Thus if a mirror is found out of adjustment after the shot — a rare thing — It can be corrected and the scene reshot immediately.

Over a period of time, many interesting discoveries have been made in the operation of the camera. We have learned how to create interesting variations in the perspective by adjustment combinations between parallax and focus, or by changing the parallax only or focus only, as the scene is being photographed. Here, precision on the part of the camera operator and assistants is most essential.

In shooting Bwana Devil, the camera was mounted on a mobile camera car, called the “Blue Goose,” for almost every take. This car, a converted 4-wheel-drive Army weapons carrier, has a fork-lift and platform on the front, operated hydraulically. This outfit enabled us to use the camera in practically any locale of the rugged mountainous location 45 miles north of Hollywood.

Although Natural Vision cameras are not limited to static camera shots, we used no moving camera shots in this production, chiefly because of the rugged terrain in which we worked. The peculiarities of 3-dimension made this possible because 3-D gives a scene such unusual depth and perspective that there is not the need for camera movement that characterizes conventional 2-dimension movies.

Obviously, this also contributed to speeding up production through elimination of time-consuming additional camera setups. Valuable time is saved because it is unnecessary to model for lighting, as in 2-dimension pictures; the 3-dimension factor takes care of modeling, giving as it does depth, roundness and added perspective to the scene. Indeed, after noting the pictorial results after the first days’ rushes, director Oboler thereafter came to settle for a single take on many scenes.

One of the characteristics of 3-dimensional movies, which made it such a spectacular innovation years ago when first presented to the public, is the way objects can be made to appear coming right out of the screen and into the audience. Today, such freak innovations must be avoided, Oboler believes, if 3-dimension movies are to assume proper stature. For this reason, such effects are employed rarely in Bwana Devil and then only to emphasize some particular action, as when an African warrior throws his spear directly towards the camera. In another instance, the ominous mood of the warriors is pointed up when, in a scene showing them advancing toward the camera with spears raised, the menacing spears project out of the screen — an unusual dramatic effect.

There is a great deal still to be learned about photography with this equipment, something that will be accomplished by trial and error, just as have the developments which we have come to employ today as standard practice. We discover something new almost every time we project dailies; this leads to new experiments and ultimately perfection.

Natural Vision’s 3-dimension system does not entail costly changes in theatre projection equipment. All that is necessary is a simple interlocking drive, joining the movement of both projectors so that the machines operate in synchronism. Already, sensing the dawn of the era of practical 3-D motion pictures, several manufacturers of theatre projection equipment have developed linking apparatus for their machines.

Both Oboler and Gunzburg are confident the public will readily accept the Polaroid spectacles necessary for viewing Natural Vision motion pictures. Some in the industry contend that need for wearing viewing spectacles will very soon turn public favor against stereo movies; but Gunzburg, in rebuttal, points to the tremendous public acceptance of stereo movies exhibited at the Festival of Britain last year — which required use of Polaroid spectacles for viewing.

As a means of developing the utmost interest in Natural Vision 3-dimensional films, and particularly in Arch Oboler’s initial production, Bwana Devil, the film will be road-shown throughout the country for an undetermined period.

Thereafter, the picture can be shown in 2-dimension, simply by screening one of the dual prints used in 3-D exhibition. Thus, any Natural Vision production has the added factor of being available for exhibition as either a 2-dimension or 3-dimension production. The function of the Natural Vision Corporation is to lease its 3-D camera equipment and to supply experienced camera crews to motion picture producers; also to supply the Polaroid spectacles necessary for viewing.

The company holds a franchise for exclusive distribution of the spectacles in the motion picture industry. Some idea of the enthusiasm which has been generated by the developments of Natural Vision and particularly by Oboler’s first 3-D feature in color is the fact that a second Natural Vision camera is now being constructed, and Arch Oboler has screenwriters working on the story for his second 3-D feature production.