Honey Boy: Father and Son

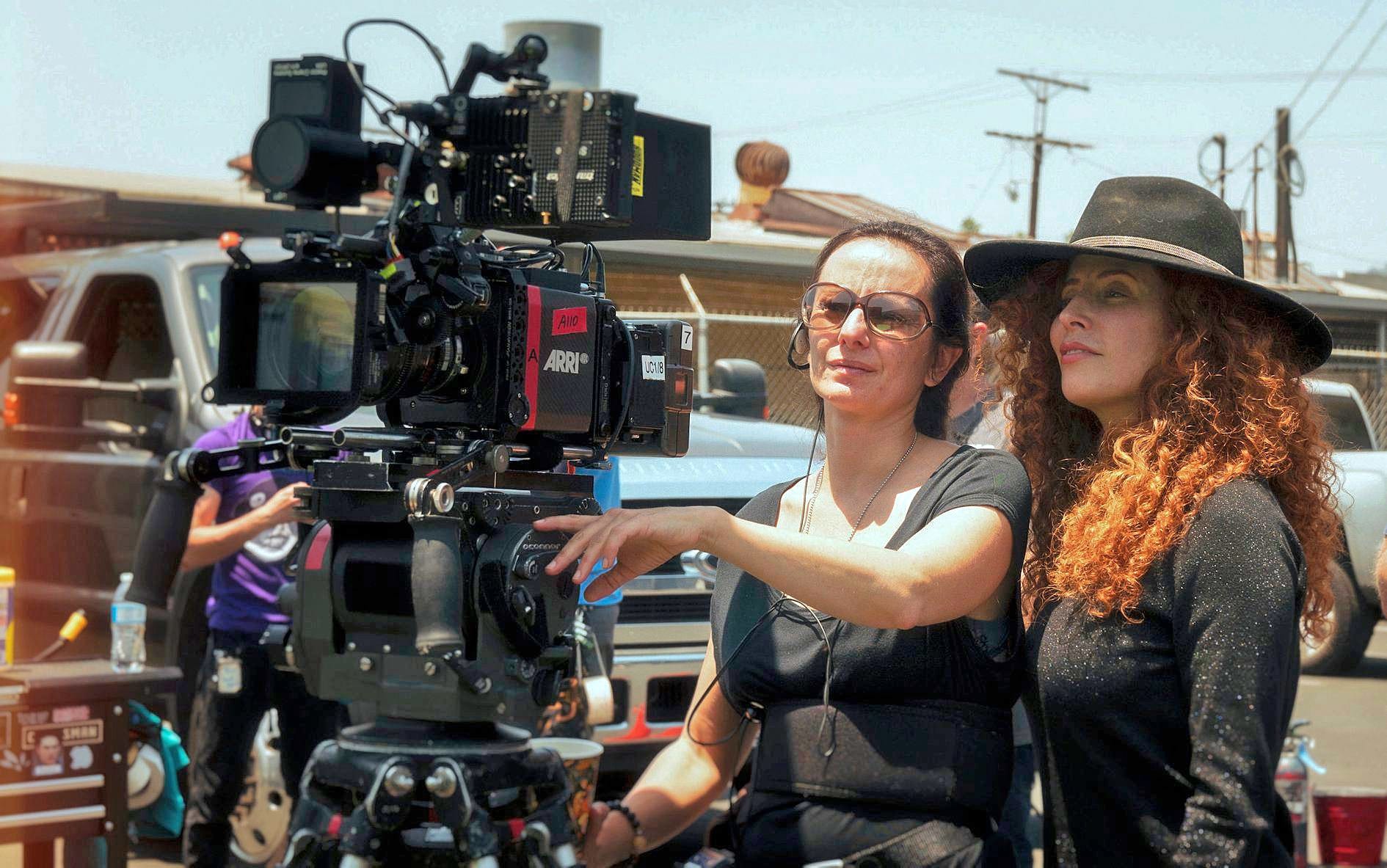

Natasha Braier, ASC, ADF brings cinematic lighting and an improvisational shooting style to this revealing drama.

Unit photography by Monica Lek. Additional images provided by the cinematographer. All images courtesy of Amazon Studios.

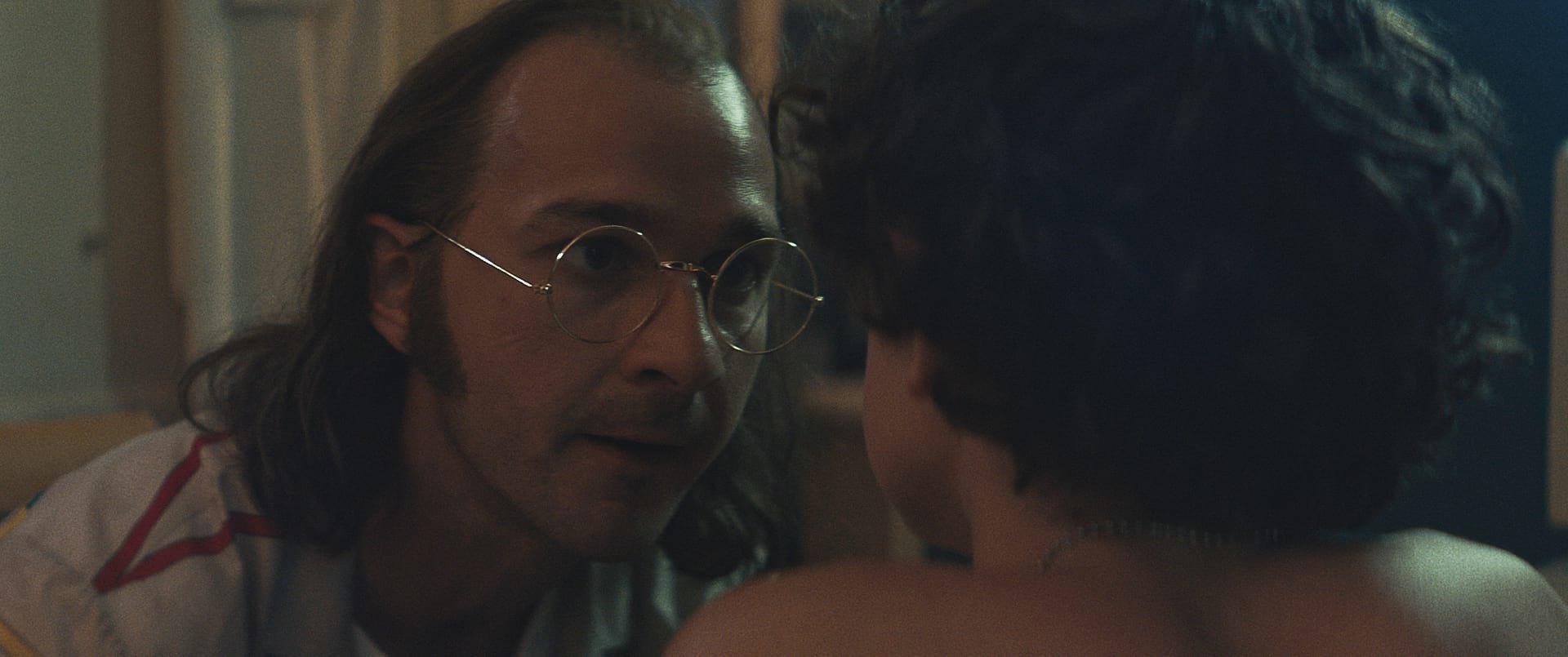

You can’t get any closer to a script than Shia LaBeouf did with Honey Boy. The story, which the actor began writing while he was in court-ordered rehab, toggles back and forth between a fictionalized version of LaBeouf at ages 12 and 22 — as a child actor under the supervision of his overbearing, alcoholic, ex-rodeo-clown father, and as a young action star who lands in rehab after a car crash. Moreover, LaBeouf chose to play his father, the cause of his diagnosed PTSD.

“It’s film therapy,” says Argentine-born, Los Angeles-based Natasha Braier, ASC, ADF. “There’s nothing more powerful than reenacting the most dramatic moments of your life. A lot of people write about them in scripts or books, but few get to act them out. You’re usually acting out somebody else’s trauma.” Though when LaBeouf assumed his abuser’s perspective, she notes, “he wasn’t doing it in a therapeutic context. He was in the middle of a set that was expecting him to be professional and do what an actor does. The pressure was remarkable.”

LaBeouf had reached out to director Alma Har’el after watching Bombay Beach — her poetic documentary about poverty and manhood in the American West — whose trio of subjects includes a bipolar boy who was the child of an alcoholic, as was the director herself. LaBeouf’s meeting with Har’el led to several collaborations prior to Honey Boy, beginning with “Fjögur Píanó,” an extended music video for Icelandic band Sigur Rós in which LaBeouf costars. He subsequently executive-produced and financed Har’el’s LoveTrue, a genre-bending documentary that interlaces its protagonists’ stories with actors playing younger versions of themselves.

LaBeouf’s Honey Boy screenplay was heavy on dialogue and light on direction. “In parts, it felt almost like a play,” the cinematographer says. “Shia was really clever giving his script to Alma. By choosing the right person, it’s not going to be just a filmed theater play. It’s going to be the visceral experience she proved she can do in Bombay Beach.”

A photographer and cinematographer herself, Har’el’s visual lyricism struck the right chord with Braier, who’s known for her expressive lighting on such features as Gloria Bell, The Neon Demon (AC July ’16) and The Rover (AC July ’14). “I liked Alma’s way of approaching things from an emotional, visceral, raw [perspective] that is very poetic — and very similar to mine,” she says. “If the director had been someone with a more conventional body of work, I wouldn’t have done the movie, [because I would have assumed] that there’s nothing here for me to do. But I knew I was with somebody who wanted the best part of me.”

Shooting a micro-budget feature in 19 days was tough enough — but Braier faced the additional challenge of bringing cinematic lighting to a documentary shooting style, necessitated by LaBeouf’s improvisational approach. Moreover, many scenes involved a child actor, Noah Jupe, playing the 12-year-old Otis. So they had to be ready for anything.

“The challenge was trying to capture the relationship between Shia and the boy in the most real, unmanipulated, documentary-like approach possible, and at the same time make it visually cinematic,” says Braier, who adds that the movie was shot via handheld and Steadicam. “How do you get that freedom for the actors and camera to move around, without compromising the lighting and atmosphere of each scene? Normally, you have to choose. Alma wanted that purity and freedom, but she also wanted expressive cinema lighting. The challenge was to get both. For that, we had to devise a very specific system.”

Not content with static 180-degree lighting, Braier lit nearly the entire production with wireless dimmable RGB LEDs that could be adjusted in-shot. “Luckily, I had that technology,” she notes. “A few years ago we didn’t, but now I really just ‘deejay’ with light.”

The lighting package included Arri S60-C and S30-C SkyPanels, Astera AX1 PixelTubes, Digital Sputnik’s DS3 fixtures and Voyager tubes, and various LIFX bulbs, all controlled through the Luminair app paired with a RatPac AKS Plus dimmer box.

In addition, Braier had LEDs mounted to the camera and positioned just outside the frame line that she could use to work her magic. These comprised the “Chorizo” and the “Julianne Moore,” each a custom-built LED unit crafted from RGB/day-light/tungsten LiteGear LiteRibbon and LiteStix. The Chorizo came in 6" and 12" sizes, and the Julianne Moore, originally created for Gloria Bell, was housed in an 11"x4" soft-box body. Each unit had a cable plugged into a wireless dimmer “and into the camera battery,” gaffer Bobby Wotherspoon says. “That sends a signal to Natasha’s light board.”

“The Julianne Moore would be dimmed up to create a spark in the actor’s eyes if the improvisation [were to] end up in a very dark place,” Braier says, “so I could guarantee that no matter how dark we ended up, we could always see their eyes.”

To light the motel interior, says Wotherspoon, “we did a lot practically, meaning Astera tubes hiding in corners, LIFX bulbs in fixtures, and then for the daytime [material], a 6K PAR out the bathroom window. When we went to nighttime mode, we had Arri SkyPanels out there so we could control the color and level.” Braier adds that “We worked in collaboration with the production designer, so that all the practical lights in the motel set were LED-controllable by dimmers, replacing conventional bulbs or tubes for LED ones. Most of the ‘light deejaying’ was done with the practical lights that were on set, [which were often visible] in the shot itself. [Motion-picture lights] were used to emulate exterior lighting coming through the windows, but the main work was done with the small practicals, including the ‘TV light.’”

Typically, camera operator Matías Mesa was in the room with the actors, while Braier would sit in the blackened tent they called “the vortex,” controlling lights with her DMX-IT dimmer board, which she now uses on every job. Wotherspoon and one of his team would sit next to her with the Luminair board. “I could keep an eye on the monitor, and Mark Farney would run the lighting cues and set the levels, while Natasha would control her Chorizos and the Julianne Moore,” the gaffer notes.

Braier adds, “I would direct the operator through a headset. At the same time, I would dim the lights, essentially working like a deejay. I always had an electrician next to me in the vortex with more dimmers/iPads, so I would do some myself and tell him how to dim the others.” If LaBeouf began the scene beside a window, for example, and then moved to a darker spot, “I would adjust as he moved, very slowly, trying to make it not noticeable. So wherever he ended up, he had interesting lighting.” This system was a handy option, since Braier couldn’t stop to tweak lights, even for close-ups, as the preference for this production was to not interrupt the actors between takes once shooting had begun.

Captured on location in Los Angeles, the production carried two Arri Alexa Minis, shooting ArriRaw and recording to CFast 2.0 cards. While mostly a one-camera shoot, both cameras rolled whenever LaBeouf and young Jupe were together in a scene. Braier operated B camera when she wasn’t working her dimmer, such as on day exteriors. Other times, Har’el or operator Valentine Marvel would operate the second camera.

The filmmakers shot anamorphic, framing for 2.39:1. “I’m in love with anamorphic,” Braier says. “It helps break the perfection and sharpness of digital, and make it all a bit more organic and cinematic. And you get lens aberrations — some magic happening there.”

Wanting a nostalgic, analog feeling, Braier chose JDC Cooke Xtal Xpres anamorphics. “On every movie, I test a lot of lenses, and I always end up using the same set of Xtal Xpres lenses made by Joe Dunton [BSC],” a renowned British cinematographer and inventor. “So these are his babies, made a few decades ago. I used them on Neon Demon, and on Gloria Bell as well. They’re a very old set of Cooke S2 and S3 lenses inside, with an anamorphic element made in Japan. They have this super-soft and gentle quality that suggests the texture of memory.”

Working with a full set of the Xtal Xpres lenses, Braier’s workhorse was the wide-angle 40mm T2.3. “But I also got a 30mm [T2.8] made specially for Michael Cimino, which is amazing and quite extreme,” she notes. “We only used it in a few shots where Lucas [Hedges, who plays the 22-year-old Otis] is losing it, and when Shia goes to the strip club and takes heroin.”

Digital-imaging technician Ernesto Joven and Braier worked with Color Collective colorist Alex Bickel in New York to create a LUT modeled on Kodak 200 ASA stock, which softened the curve in the toe and shoulders, and slightly desaturated the colors. “I wanted this kind of nostalgic tone, like a subliminal memory,” Braier says. “We made the whole movie looking at that LUT on the monitor, so when we went to grade with Alex, he didn’t have to do much. Just by applying the LUT, he was seeing exactly what we were seeing on set, because it was his own color science. Since the look of the film was 100-percent nailed down before we even started the grade, we could use that time to play with more challenging moments, where I hadn’t had time to do everything in camera because of the nature of the beast.” Bickel graded with Blackmagic Design DaVinci Resolve 15 on Linux, working directly from 2.8K ArriRaw files.

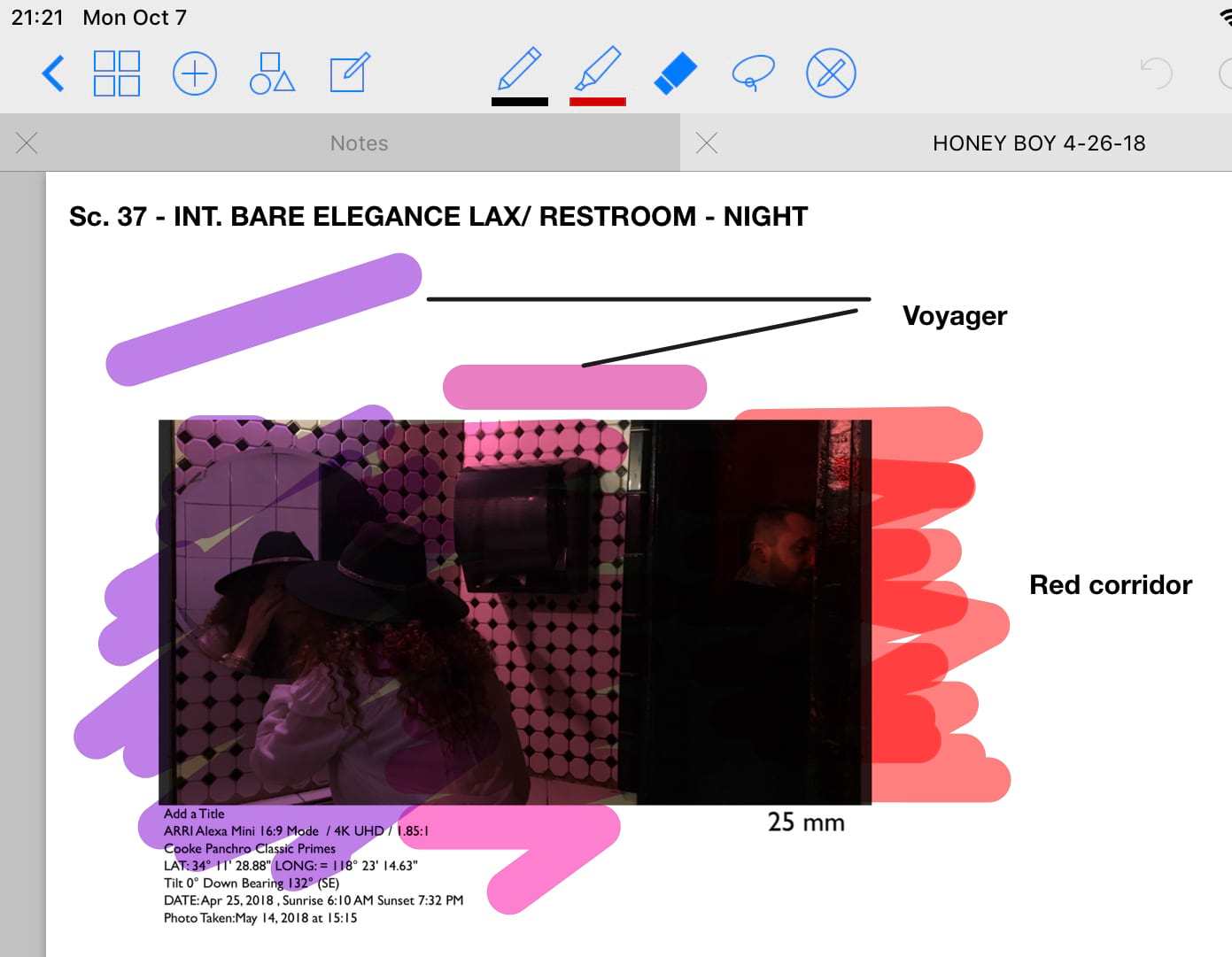

True to form, Braier made use of color to bolster the emotional content of the script. One instance comes after a major fight between father and son — who live together at a low-rent motel — that sends the two seeking solace in separate directions. This is when LaBeouf’s character seeks refuge in a strip club, falls off the wagon and takes heroin — a sequence that cuts back and forth with Jupe’s character finding comfort in his budding friendship with a young prostitute (FKA Twigs), who also lives at the motel. They swim in the pool, play “mime,” and curl up together for the night.

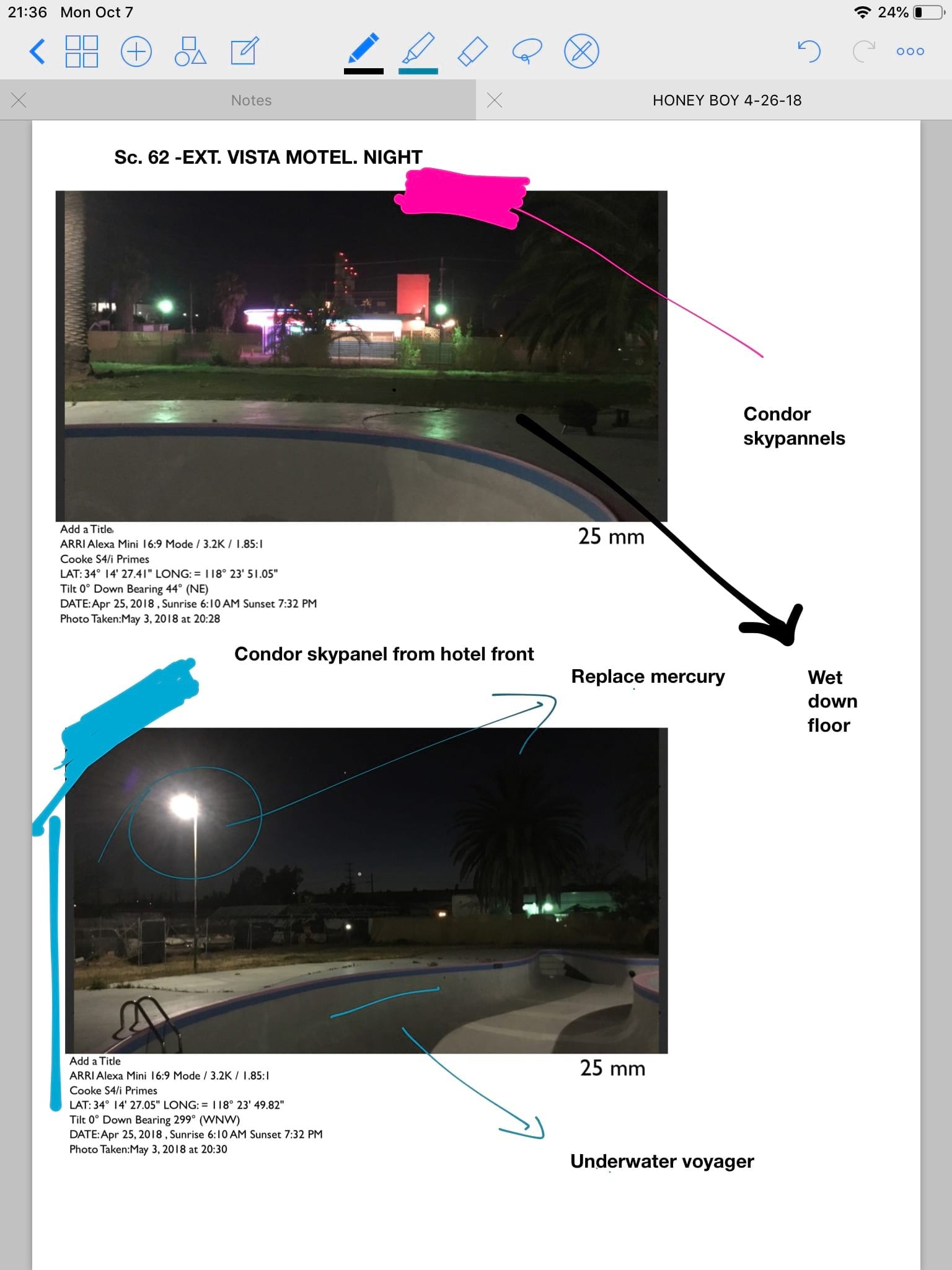

Mercury-vapor streetlights, Arri SkyPanel S60-Cs, a gelled 6K on a condor, and a Digital Sputnik Voyager tube were employed to illuminate the motel pool for night exteriors with actors Noah Jupe and FKA Twigs.

Braier used the pink, blue-purple and green of the motel’s retro sign to motivate lighting in the pool, while the same colors played in counterpoint in the strip club. “I thought it was nice to have pink representing the female presence,” she says of the motel pool area. “After all the toxicity of the relationship with his father, he gets comforted by this feminine energy. At the same time, the father is going to the strip club and getting comforted in his own way, but it’s the dark side of the feminine. The more maternal and bright side is with the young man and the prostitute. I thought [these two sequences were] beautiful mirror images of each other. I wanted to do that visually as well, so I used the same color palette but in different proportions.”

Lighting the pool area began with six preexisting mercury-vapor streetlights. A SkyPanel S30-C was rigged to the top of each lamppost, augmenting their greenish light. The pink of the motel’s neon sign was extended and exaggerated with a gelled 6K on a condor, as well as a wireless Voyager tube that added illumination to the pool. Another condor with six SkyPanel S60-Cs aimed through a 12'x12' Quarter Grid was dialed to “the equivalent [of] Peacock Blue/Turquoise gel,” Braier says, which was intended to emulate “a mercury-type streetlight, or a sign coming from a building out of shot.” All added up to a dreamy feeling in the pool, carried over into the motel room with Astera tubes. The Asteras again came into play inside the strip club.

Braier created notated images on an iPad to plan the production’s lighting, with particular attention to color. Seen above are lighting plans for a strip-club restroom where the father seeks refuge in drugs, and the pool where the son finds comfort with his friend.

Given the production’s shoestring budget, there wasn’t much ability to alter locations. They did, however, manage to paint interiors at the Pink Motel in Sun Valley, Calif., taking it from flamingo pink to a dark teal blue. “We wanted a color palette reminiscent of posters from the old rodeos,” Braier relates. “They have this old, rusty, earthy quality, with blues, yellows, oranges and reds.”

Honey Boy’s most difficult and costly shots were not the action-film escapades and fiery explosions that begin the movie in the montage of Otis-as-star. Rather, it was the motorcycle shots peppered throughout the film — father and son’s sole means of transportation. “We had a very specific idea of how we wanted to portray those different moments, and how the physical contact was different from one scene to the next,” Braier relates. Early on, for instance, a wide shot establishes the father’s reckless driving. Another shows him knocking his helmet back into Otis’, annoyed at the child’s head resting on his shoulder. In later shots, says Braier, “it’s all about the close-up of the kid really hugging his father. At that point in the movie, that means so much. So for that close-up, we made sure to have a flare in that moment, to make the image more magical and poetic.”

To economize, they crowded all the motorcycle shots into a single day, and sprang for a process trailer. “We weren’t allowed to drive a motorcycle for real with a kid in the back,” Braier notes. The trailer carried a Technocrane paired with a Scorpio head. “Because we had the arm, we could get shots in all these different positions really quickly, without having to [attach] rigs to the motorcycle,” Braier says. “Matías was controlling the arm and operating the camera, while I was operating the zoom.” They drove around their circuit, going tighter or wider and flaring the sun from various sides. “We collected everything we needed in a few hours of the late afternoon and at sunset, so we had the looks for the different times of day.”

Braier’s kit, the cinematographer notes, contains “different torches that create different types of flares. We handheld the torches, aiming them at the lens, or rigged them in the matte box.”

Given the small crew, compressed schedule, and dictates of documentary-meets-poetic-fiction filmmaking, Honey Boy had its logistical hurdles — yet as Braier relates, there were emotional triggers as well, and not just for LaBeouf. Watching him push through such painful material, she says, “It touches you. You’re not just a cold technician dimming the lights and resetting for Take 2."

“But I can tell you that every day at the end of the day, my crew and I felt very happy,” the cinematographer adds. “Every morning we felt challenged. Every day we had to invent a new system, or a new way to solve a situation where we had very little control. But we pulled it off. We really liked what we did — capturing that aliveness, and at the same time bringing our magic to the table.”