Looks That Kill: The Neon Demon

Natasha Braier, ADF adopts a bold palette for director Nicolas Winding Refn’s stylized tale of vanity run amok.

Photos by Gunther Campine and Natasha Braier, ADF; screen grabs by Ernesto Joven. Photos and screen grabs courtesy of Amazon Studios.

The myth of Narcissus gets a contemporary spin in The Neon Demon, a psychological horror tale — as darkly comic as it is macabre — about the excessively high value that modern culture places on physical beauty. Set in the competitive world of modeling, the movie follows 16-year-old Jesse (Elle Fanning), a naïve newcomer whose unadorned beauty and shy manner immediately attract the attention of the Los Angeles fashion industry’s top photographers — and the enmity of the more seasoned models.

“Society has become so distorted,” laments director of photography Natasha Braier, ADF, who sat down with AC during a 48-hour break between jobs. The cinematographer — who was born in Argentina and earned her master’s degree in cinematography from the U.K.’s National Film and Television School — reflects, “We are all trapped in a culture of youth that promotes the idea that you are worth more if you are beautiful.”

This emphasis on and pursuit of an idealized beauty was a major impetus behind Danish writer-director Nicolas Winding Refn’s script, which was co-written with Polly Stenham and Mary Laws. “The window when one is considered beautiful, or desirable, or ‘perfect,’ is getting shorter and shorter, and it’s moving toward a younger and younger age,” Refn says, speaking by phone from his home in Copenhagen.

Given the story’s milieu and subject matter, Braier had hoped to shoot on film, but Refn urged digital origination, making The Neon Demon the first feature the cinematographer has shot digitally. Her primary concern, she says, was that “this picture is about beautiful women. How do you make somebody appear flawless on digital?”

Since anamorphic was the lens decision from the beginning, choosing the right glass to pair with the produc-tion’s Arri Alexa XT camera was crucial. “I needed super-soft lenses to keep the actresses looking as beautiful as possi-ble,” she says. “I remembered a set of anamorphic primes I loved when I attended film school in London — JDC Cooke Xtal [Crystal] Express. They were made by Joe Dunton; the lenses are old Cooke S2s and S3s inside, with an added anamorphic front element designed in Japan.”

Dunton was an important figure for Braier when she was in film school and just starting her career, lending her his Xtal Express lenses to shoot a number of short films. Panavision eventually bought Dunton’s company, including its lens inventory, so Braier asked Guy McVicker and Cathy Peirce Ouellet at Panavision Hollywood if they could “fish out the Xtals for me. Once we had them, I went to Panavision Woodland Hills to test them against six other sets with [ASC associate and Panavision’s vice president of optical engineering and lens strategy] Dan Sasaki, who ended up loving the Xtals as much as me, and tuning them for me to get them to work at their optimum qual-ity. The way they refract and diffuse light is really amazing. They keep the skin tones looking like porcelain. Depending upon where the light is coming from, they also produce a random array of flares and weird aberrations that help break the digital feeling.”

The production’s Xtal Express package included 32mm, 40mm, 50mm, 75mm and 100mm primes. “Shooting at T4 you get a bit more defi-nition in the eyes,” says Braier. “At night we sometimes had to shoot at T2.8 because there just wasn’t enough light.”

In addition to the Xtal Express lenses, the filmmakers carried Panavision C Series 150mm and 180mm primes and a Panafocal 50-95mm (T4) zoom.

Braier recorded ArriRaw to Codex XR Capture Drives mounted in the Alexa XT’s internal XR Module. She says the Xtal Express optics offered a good counterbalance to the sharpness of the camera. Lest the images still look too clean, however, she sometimes smeared an optical flat with a small amount of Vaseline or other grease to cut the digital feel. She also occasionally placed lighting units inside the matte box. “We cut a few half-round diffuser aluminum channels and placed LED hybrid LiteGear LiteStix ribbon inside of them,” gaffer Manny Tapia says. “We then Velcroed those to the inside of the matte box and pointed them at the lens.” Braier adds with a laugh, “It was like flashing [the film] in the old days.”

Refn invited AC to visit the set during the very first night of production, on location in the attic of the Los Angeles Theatre, a historic movie palace in the once-grand Broadway theater district of downtown L.A. Production designer Elliott Hostetter recounts that he, Refn and Braier were scouting the theater’s lower floors when, on a whim, they decided to climb up to the attic. “It was just a big, dusty space used for storage,” says Hostetter. “But it had this huge window at the far end of the room with a 2.35:1 ratio that was just perfect for this slow dolly reveal [that opens the movie].”

Refn strives to shoot his movies in chronological order, so this first shot of principal photography is also the open-ing shot of the edited feature. In the scene, Jesse wears an electric-blue metallic dress and reclines on a silky silver sofa. Her eyes, dotted with sequins, are open but unblinking; blood cakes her neck where her throat appears to have been slashed. The frame remains static until a sudden eruption of flashbulbs — simulated via a Lightning Strikes 8K Paparazzi light mounted on the camera dolly — cues the camera to slowly pull back, revealing that the setting is not a grisly crime scene, but a fashion shoot:

As the camera dollies farther back, the enormous, rectangular window comes into frame around the gold-papered wall behind the couch. Outlined in two thin ribbons of bright-red neon light, the window reveals the set piece to be just that: a set. “The red neon around the glass was Nicolas’ idea,” says Hostetter. “I loved it.”

According to Refn, “The first shot of a movie defines the style.” Indeed, the director’s style is marked by such tropes as frames within frames and a frequently static camera. Eschewing Steadicam, handheld and overt camera movement, he creates tension and energy within the frame’s confines. “For me,” he submits, “it’s very much about the composition inside the frame. The only visual clue I gave [Braier] was that I wanted everything to feel like a static photographic image.” (See the director’s additional throughts on the subject here.)

Refn’s signature style also includes the use of slow motion. As Braier notes, “We shot most of the film at 24 fps, but some at 60 fps — using the slow motion to create different emotional textures and heighten specific moments.”

The production also employed bold contrast between heavily saturated colors, and an almost tactile sense of texture. Both Braier and Hostetter referred to the work of American artist James Turrell and late French fashion photographer Guy Bourdin for inspiration. Bourdin, Hostetter notes, “was a total master of texture. This had a huge influence on us. The textures of surfaces can really help add a sense of dimension. Plus, Guy’s work was all about sex, death and glamour, which was perfect for this story.”

Braier and Tapia devised a lighting plan that would further accentuate the film’s colors and textures. “For the opening scene, two 4' T12 [fluorescent] practicals, with 1⁄2 Minus Green added, were placed camera-left of the sofa,” recalls Tapia. “A 4-by-4, 3,200-degree Kino, with 250 diffusion, loomed over the back of the couch [and was later erased in post], providing a toplight that brought out the texture of the wallpaper and added shine to Jesse’s dress. Finally, a Source Four — with a 19-degree lens and both a 3⁄4 CTB and a theatrical-style Deep Blue — added a pronounced blue tint from camera-right of the sofa.”

To provide contrast with the interior lighting, Braier had two Digital Sputnik LED units placed at street level to up-light the limited view through the window. The DS LEDs had been recommended to her by Greig Fraser, ASC, ACS, who used them on the upcoming Rogue One: A Star Wars Story. “He is in love with the Sputniks,” Braier says with a laugh. “Greig called Kaur Kallas, co-founder and CEO of the company, and said, ‘You have to help Natasha.’”

The DS LED units are the brain-child of Kallas and his brother Kaspar (see New Products and Services, AC Oct. ’15). “Our system is based on a modular [concept], with individual light modules serving as the basic building blocks,” explains Kaur Kallas. “The DS 3 has a single power supply that controls up to three individual light modules, which can either be grouped together or used separately; the DS 6 has six light modules pre-built into a frame; and we are now launching a DS 1, which is a single light module that can be powered by batteries. You can also panel the light modules into whatever shape or size you want — rather like Legos!”

Braier says Tapia bought a DS 3 set that was used throughout the shoot, “and Kaur very generously lent us addi-tional units for our bigger scenes. I played a lot with color on this film, and I couldn’t have done it without their lights, which can be set up very fast. They trained our guys how to use the Sputniks, and they taught Manny and me a lot about digital colorimetry. Kaur comes from the digital postproduction world so he is a total expert on it. Talking with him prior to the shoot was like having a master class — with invaluable tips on how the color capture works on the Alexa sensor and how to handle the extreme colors I was planning to use on set.”

The Neon Demon was shot in and around Los Angeles, primarily on practical locations. One of the biggest setups, in terms of both lighting and staging, was for a nightclub sequence shot inside the Orpheum Theatre in downtown L.A. on the second night of principal photography. Jesse is invited to the party by makeup artist Ruby (Jena Malone), and they arrive to find hundreds of revelers mingling amid a hip but ominous ambience. “Jesse is entering this new world that is totally alien to a girl from a small town,” remarks Braier. “It’s like Dorothy landing in Oz.”

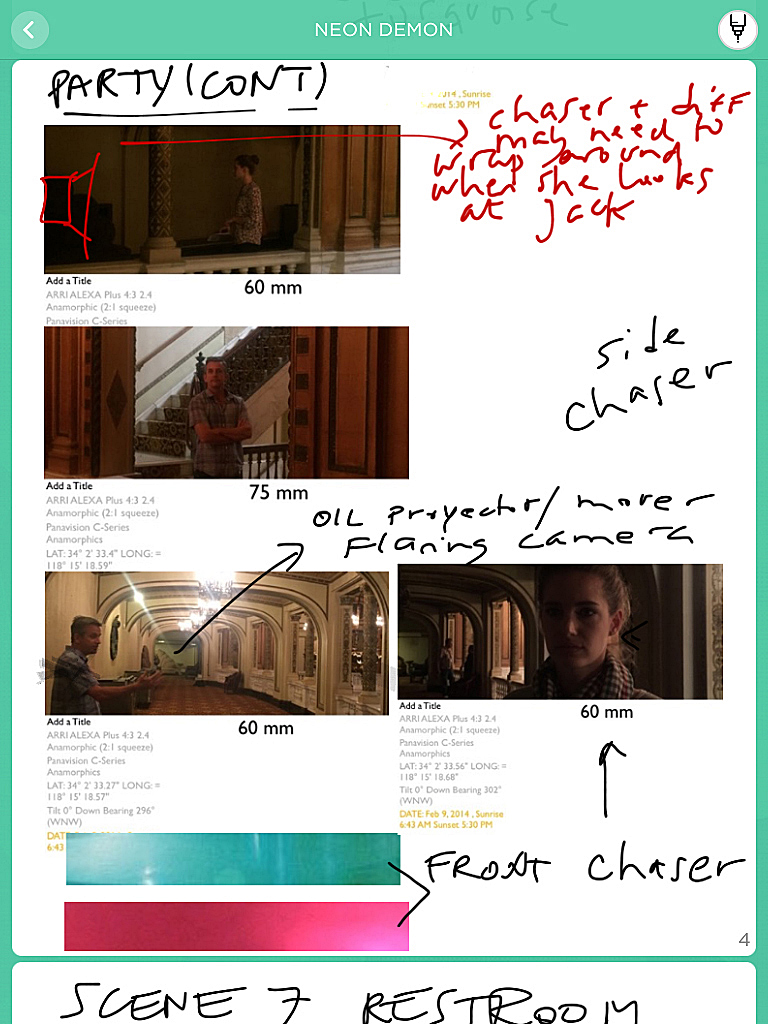

Stephanie Martin, the operator on the single-camera shoot, describes bringing the two women into the building: “An elevator door opens on the first floor, and we dolly back as Jesse and Ruby step out and walk down the corri-dor. [The camera dollies parallel to the girls as they climb the stairs to the upper-gallery level and] down a 30-foot stretch, as they maneuver through and around the crowds to reach two friends of Ruby’s, experienced models Sarah and Gigi [played by Abbey Lee and Bella Heathcote, respectively].”

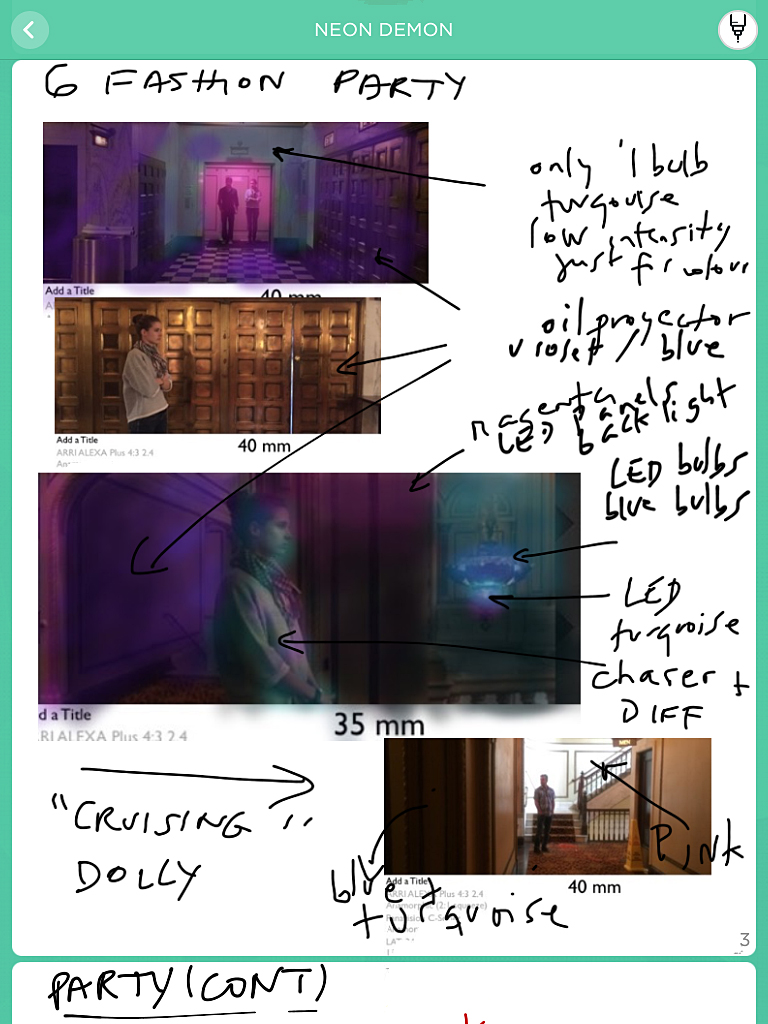

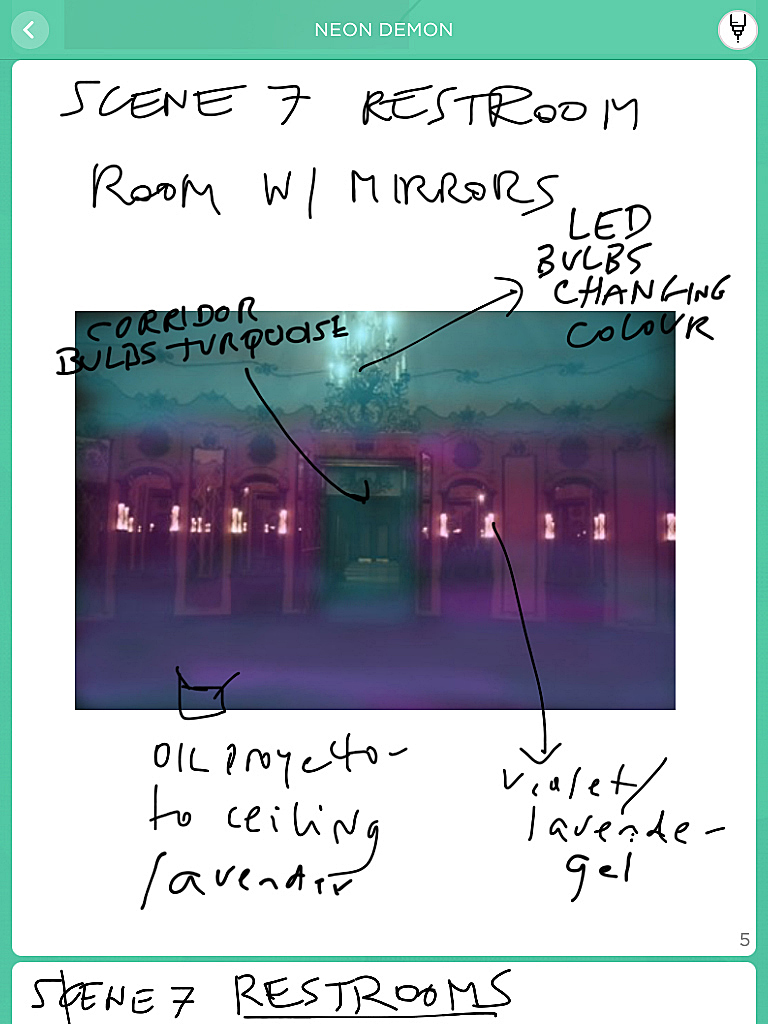

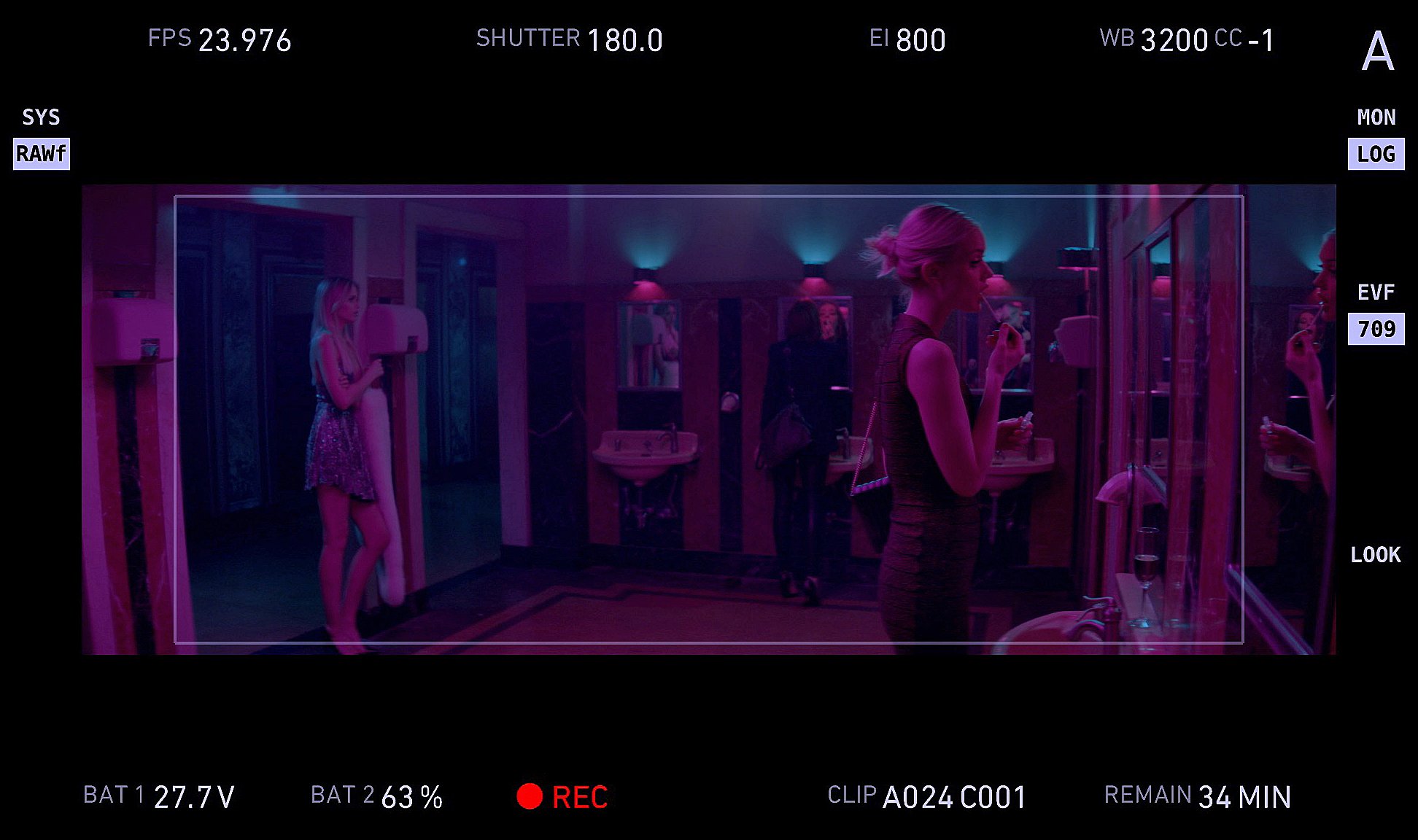

Here are more of Braier’s notes on the scene, leading to a catty confrontation in the ladies' room between Jesse, Sarah and Gigi:

Six LED panels provided magenta output and backlit Fanning and Malone as they walked in profile. These panels were the result of Tapia’s approaching Sean Goossen and Al DeMayo at LiteGear and asking them to create what the gaffer describes as a “custom Frankenstein” light. “At the time, [LiteGear] had just started build-ing their Hybrid LiteMats,” Tapia says, “but they weren’t really building anything with RGB capabilities in a 2-foot-by-3-foot size, which is what I figured I would need. So they built six three-panel LiteMats [based on their LiteMat 3 unit] that [offered daylight, tungsten] and RGBA all in one unit. We ran them exclusively wireless so I had full dimming control in my hand. The lighting crew affectionately called them ‘Manny Mats.’”

Also integral to the walking sequence with Fanning and Malone was an oil-wheel projector with colored-glass gobos, which projected a lava-lamp pattern over the actresses’ heads as they exited the elevator; this same unit was employed to light the stairs area from the out-of-frame ground floor. A couple of 1,500-watt Clay Paky Alpha Profiles, each with its own gobo, produced a simi-lar effect during the dolly move. Practical light came from five large chandeliers, each containing 50 to 60 bulbs. “We wanted a lot of color, but it was too expensive to replace all the regular tung-sten bulbs with RGB LEDs,” acknowl-edges Braier. “The electricians replaced most of the bulbs with [‘party-blue’ globes] and used 10 to 15 MiLight RGBW LEDs in each chandelier.”

Compatible with standard practical lightbulbs, the MiLight LEDs, as Tapia explains, “have Wi-Fi capability. The brightest at the time were 6-watt globes, or the [approximate] equivalent of a 20-watt incandescent bulb.” Using a hand-held remote, Tapia could then swirl through color options while also pulsing the MiLight LEDs up and down.

“I chose a range of colors,” Braier says, “and got Manny to slowly go through them, creating a kind of hypnotic and almost imperceptible shift in color.” Adding still more color were Digital Sputnik DS 3 LEDs, which would also slowly shift in color and intensity, that lit the chandeliers from the ground.

Tapia readily acknowledges that The Neon Demon called for a different approach to lighting than other projects on which he’s worked. “Not only is there a lot more color, but Nicolas uses color to move the story forward and to lead the audience in certain directions,” the gaffer notes. “From my early discussions with Natasha, I knew we would need a lot of gels for the traditional incandescents and HMIs.” Cinelease and Tapia’s own company, Tap In Power, supplied most of the lighting equipment.

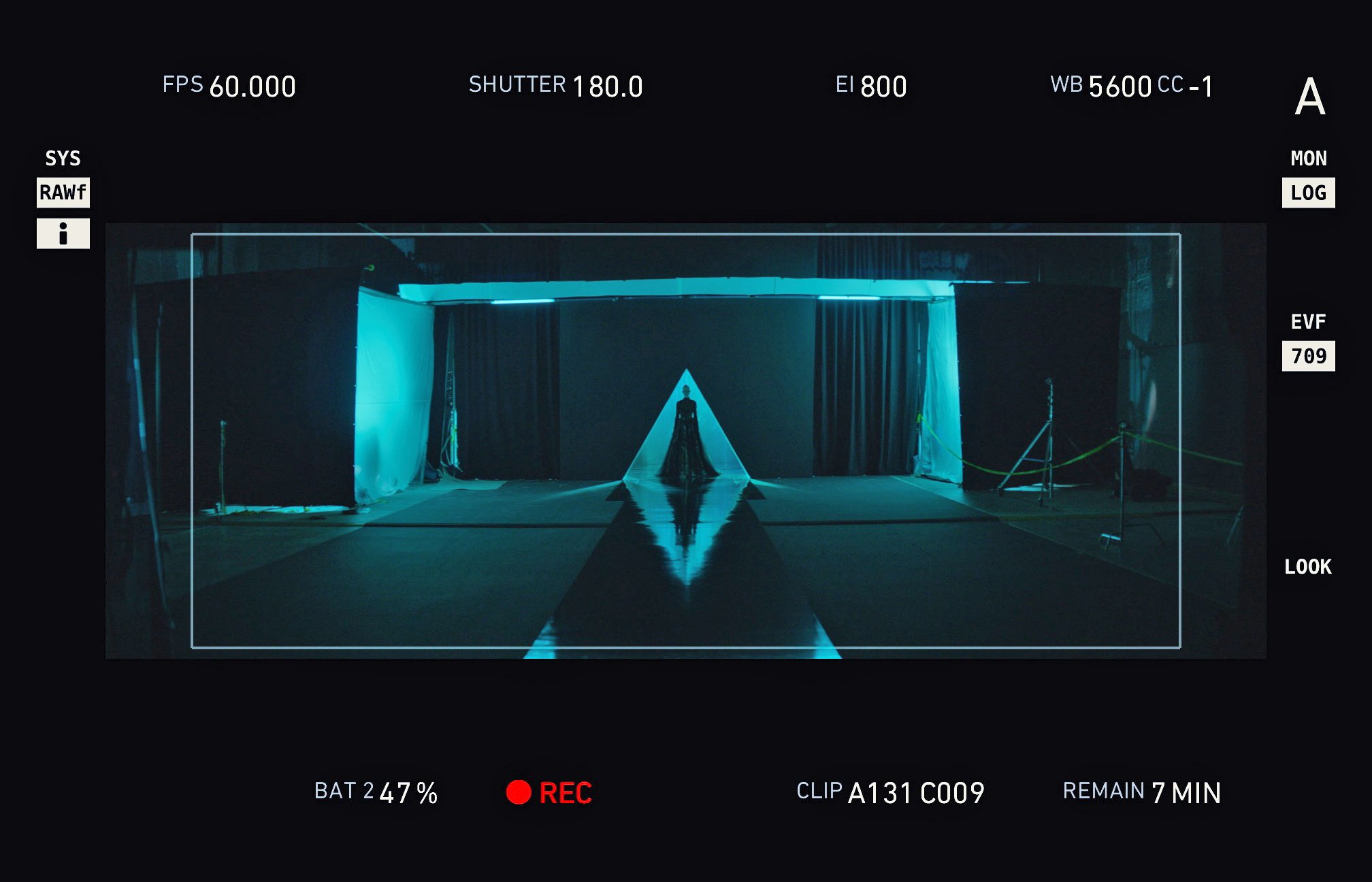

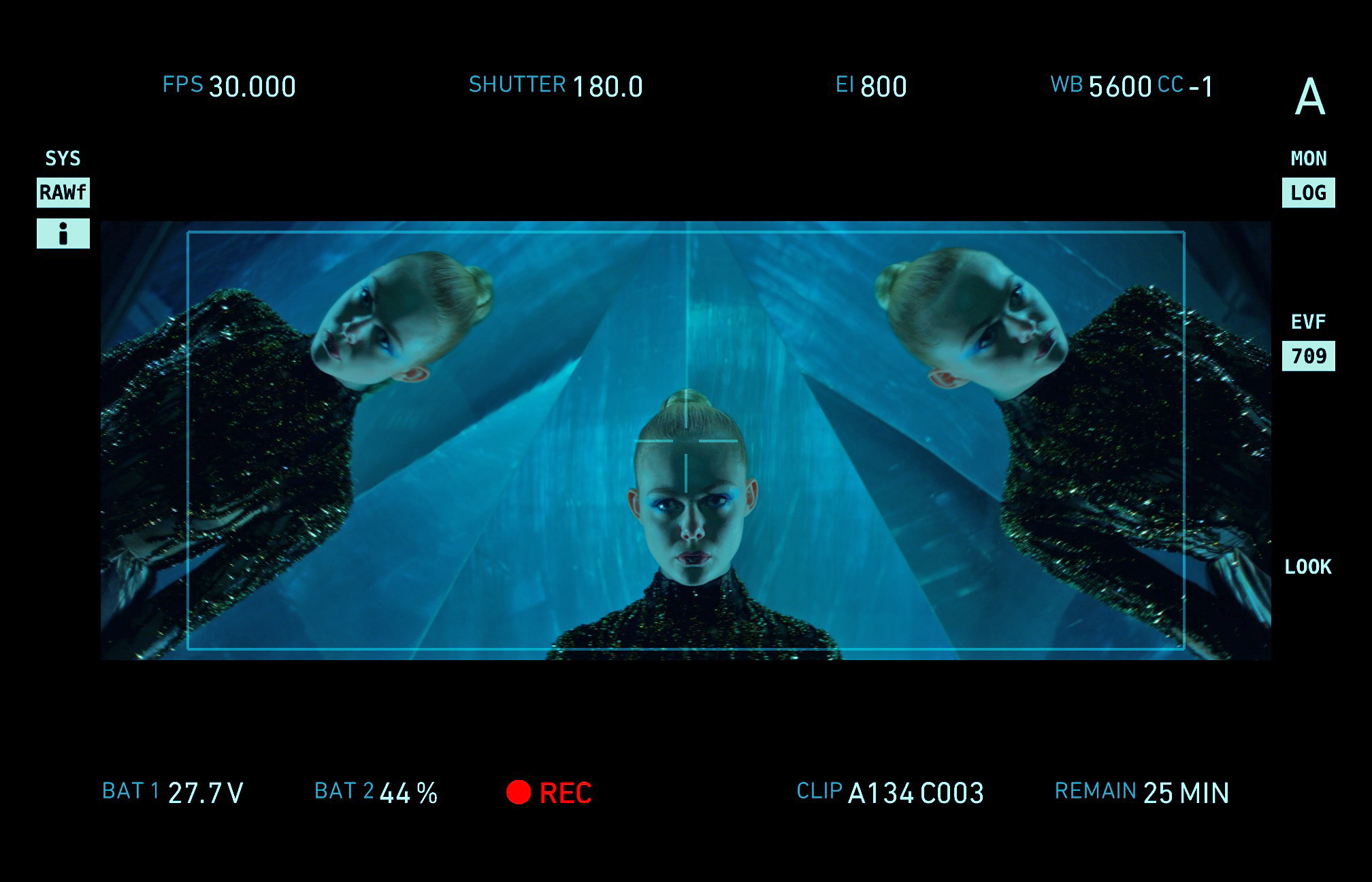

The major turning point for Jesse — and the movie — is the Narcissus scene: the big fashion show, during which Jesse catches her reflection in a mirror and falls in love with her own beauty. The scene begins with a group of runway models standing backstage, waiting for their cue. When it’s Jesse’s turn to step onto the runway, the other women disappear and the imagery turns abstract. “It’s like we go into Jesse’s head, into her mental state,” says Braier.

The sequence was shot at Calvert Studios in Van Nuys, Calif., where a large triangle of mirrors was constructed to serve as the doorway to the catwalk. Mirrors above and on both sides of the triangle reflect Jesse as she makes her entrance; Hostetter describes the config-uration as “a mirrored cave, or a kind of inverted pyramid that was faceted in such a way that the light bounced all around, as did Jesse’s reflection. It was almost like Jesse was inside of a diamond.” Jesse walks down the runway toward a double triangle in a star-like configuration, outlined in neon-blue light, which was accomplished with RGB LiteRibbon. Undulating blue light surrounds her as she walks; the rest of the room is dark.

To create this watery effect in the wide shot of Jesse walking, Braier explains, “we bounced Sputniks [outputting] blue light into big pieces of silver and white silk that the grips would rustle. We then cut to a medium shot of her, at which point Elle is actually walking on a treadmill.” The use of the tread-mill was per Refn’s directive, Braier notes, “so Elle could walk on and on without having to cut every 60 feet, and he could keep the shot running and work on the performance without technical interruptions. The grips and electrics made a patchwork of gels — green, blue and turquoise. We put them on a big frame that rotated in front of [an Arri M40 bounced into an 8-by-8 silver lamé].” Tapia describes the gel rig as “a sort of stained glass on a pinwheel that could be spun manually.”

“That continued the watery effect,” Braier adds, “but with a slight change in colors. As Jesse reaches the star, we wanted the water effect to become even more pronounced, so we bounced [three of the Digital Sputnik DS 6 units] into [pans] of water that had [broken bits of] mirrors in the bottom of them, and the textured water effect bounced back on Elle.

“Conceptually, the idea is that when Jesse reaches the star structure, she glimpses herself in a three-paneled mirror and undergoes a kind of transformation,” the cinematographer continues. “It’s as though she is seeing both herself and another side of herself — a more evil Jesse. At that moment, the triangle changes colors from blue to red.” Feeling empowered, Jesse kisses her reflection in the mirror, turns around and walks back to the entrance triangle, which now also glows red.

There was, in fact, some sleight of hand involved in Jesse’s kissing of the mirror. To obtain the most pleasing angle for Elle’s reflection, Refn actually had Fanning gaze into the star as if she were looking into a mirror, with plans for visual-effects artists to add her reflection later. On a whim, the filmmakers kept the camera rolling as Fanning walked back to the entrance, where her image actually was reflected in the mirrors surrounding the triangle. Fanning kissed her reflection in those mirrors, and that shot was then edited into the footage at the other end of the runway. Because the sequence is so abstract — “and we didn’t care about the ‘reality’ of it so much,” Braier notes — the cut doesn’t call attention to itself.

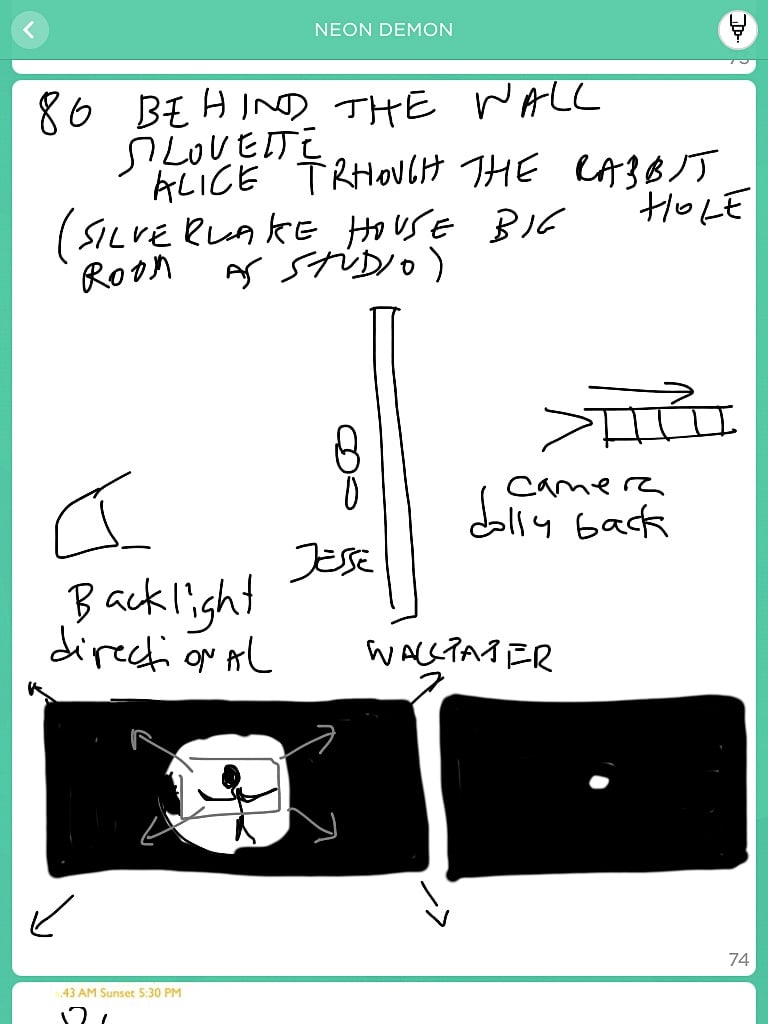

After Jesse returns to her motel room, someone tries to pry open her door, fails, and then moves on to the adjacent room, where he proceeds to rape the girl inside. Jesse stands frozen as the camera pans across her room to the wall she shares with her neighbor; the camera stops on the wall, and Jesse re-enters the frame, kneeling down to listen. The scene then cuts to a silhouette of her listening, as if shot through the wall from the adjacent room. Framing Jesse’s silhouette is a circular black “iris” effect that gets smaller as the camera tracks backwards, away from Jesse.

“This is a key moment in the movie,” says Braier, “which we christened ‘Alice through the rabbit hole.’ In this moment the movie takes yet another turn in its language and distances itself even more from reality. The camera goes to the room next door, where the rape is taking place, and it’s ‘magically’ shooting Jesse’s silhouette through the wallpaper texture. Then it pulls away, revealing Jesse inside an iris — old silent-movie style — and then pulls away even more, making the ‘hole’ smaller and smaller in a sea of black. This was a moment where we were making a punctuation, and saying that we are now going into the rabbit hole, into the abyss, the darkness, and everything is possible.

“Elliott printed an 8-by-8 piece of material with the texture of the wall-paper, which we rigged on a standard silk frame. We positioned Elle on one side of it and lit her from behind with a directional [800-watt Jo-Leko HMI with a partially diffused iris], creating the iris on camera with her silhouette inside. On the other side of the wall, we had the camera on a track, perpendicular to the wall, so it would pull back as far as the size of the stage. On the dolly we rigged a small soft LED light with Depron that lit the wallpaper at the beginning of the shot, showing its texture, and we dimmed it down as we got away from the wall. So at the beginning of the shot you do see the wall-paper texture superimposed on Jesse’s silhouette, but as we pull away, the wall-paper disappears and we end up with a more abstract image of just her in the rabbit hole that gets smaller as the camera is pulling away from it — like [she’s] falling down.”

Frightened, Jesse phones Ruby and seeks refuge at the mansion where her friend is housesitting. There, the story’s final chapter begins. Gigi and Sarah arrive in the movie’s sole Steadicam sequence — which ultimately involves a chase inside the house — that transitions to a “long, side dolly shot,” as Braier describes it, as the action transitions to the swimming-pool area.

Braier was particularly pleased with the mix of lighting on the mansion’s back terrace, where the four women converge. Eight to 10 Kino Flo 4' four-banks gelled with Peacock Blue were placed inside the mansion’s empty swimming pool, while violet-hued Sputniks bounced into a large silk just off-camera, behind and to the left of the diving board, creating a strong violet wash over the scene.

Partially color-blind, Refn is able to distinguish reds and blues, which is why those colors dominate his work. “I don’t know what I can’t see,” he admits. “But if I can’t see it, I can’t relate to it. This forces everyone on the crew to pretty much approach the production with the same handicap that I have.”

Braier adds, “A lot of colors look the same to Nicolas’ eye. If you can’t pick up on color separation, things look flatter, but contrast compensates for the lack of depth perception. So, that’s why Nic loves contrast and wants a lot of it in his films. I am also a very contrast-y person and I’m always trying to create depth with contrast, so it was easy to give him what he wanted.”

Braier had been interested in collaborating with Refn for some time. She refers to the director’s work as “poetic,” and admires his insistence on shooting in chronological story order. “His process is not dictated by the ‘time is money’ paradigm as most films are, where everything occurring at one location has to be shot on the same day or consecutive days,” she observes.

The director and cinematographer collaborated on the film’s final grade with freelance colorist Norman Nisbet, who graded the movie in 4K with Blackmagic Design’s DaVinci Resolve at Act 3 in Copenhagen for a 4K final deliverable. Due to previous commitments, Braier had to move on before the work was completed, but Refn remained to supervise the comple-tion of the grade. The Neon Demon premiered in May at the Cannes Film Festival, where it screened in competition.

In addition to Tapia, Martin and Sasaki, Braier emphasizes the contributions of digital-imaging technician Ernesto Joven, 1st AC Hector Rodriguez, 2nd AC Eric Jensch and key grip Amos James.

In turn, Refn credits Braier for being “instrumental [in achieving] the look I wanted for the film. She is inventive — and absolutely amazing to work with.”

TECHNICAL SPECS

2.39:1

Digital Capture

Arri Alexa XT

JDC Cooke Xtal Express; Panavision C Series; Panafocal zoom

The cinematographer was invited to join the ASC in 2018. She was later profiled here, and discussed her work in the ASC Award-nominated film Honey Boy (2019) here. She and Refn would collaborate again on a marketing campaign for Hennessy.

AC previously spoke to Refn about his bleak historical drama Valhalla Rising (2009) and subsequently covered his collaboration with Tom Sigel, ASC on the thriller Drive (2011) and Larry Smith, ASC, BSC on the surreal drama Only God Forgives (2013).

For access to 100 years of American Cinematographer reporting, subscribers can visit the AC Archive. Not a subscriber? Do it today.