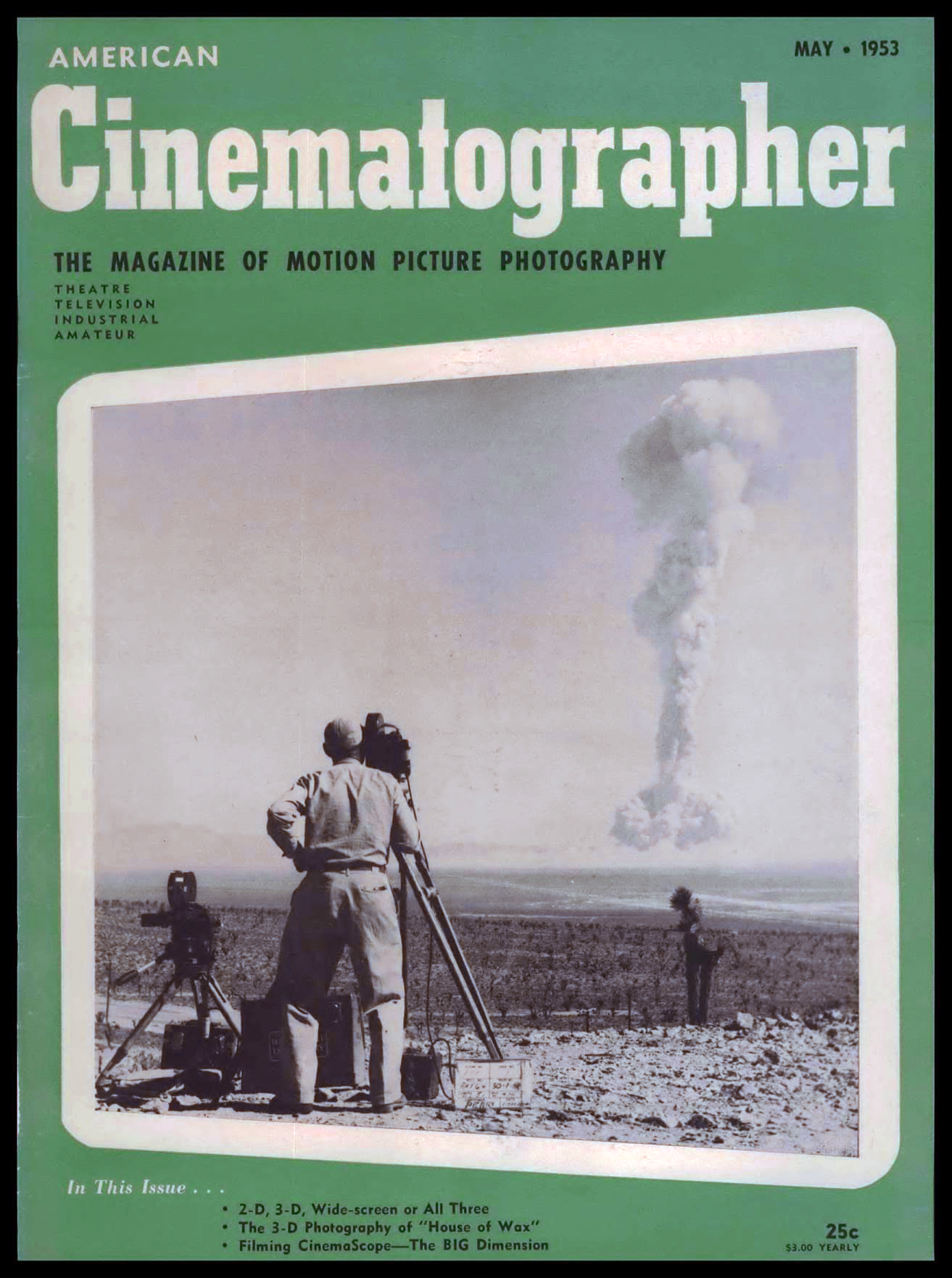

Terror in 3-Dimension: House of Wax

Peveral Marley, ASC’s commendable 3-D filming of Warner Bros.’s horror picture demonstrates the dramatic value of stereo cinematography.

J. Peverell Marley, ASC’s commendable 3-D filming of Warner Bros. House of Wax demonstrates the dramatic value of stereo cinematography.

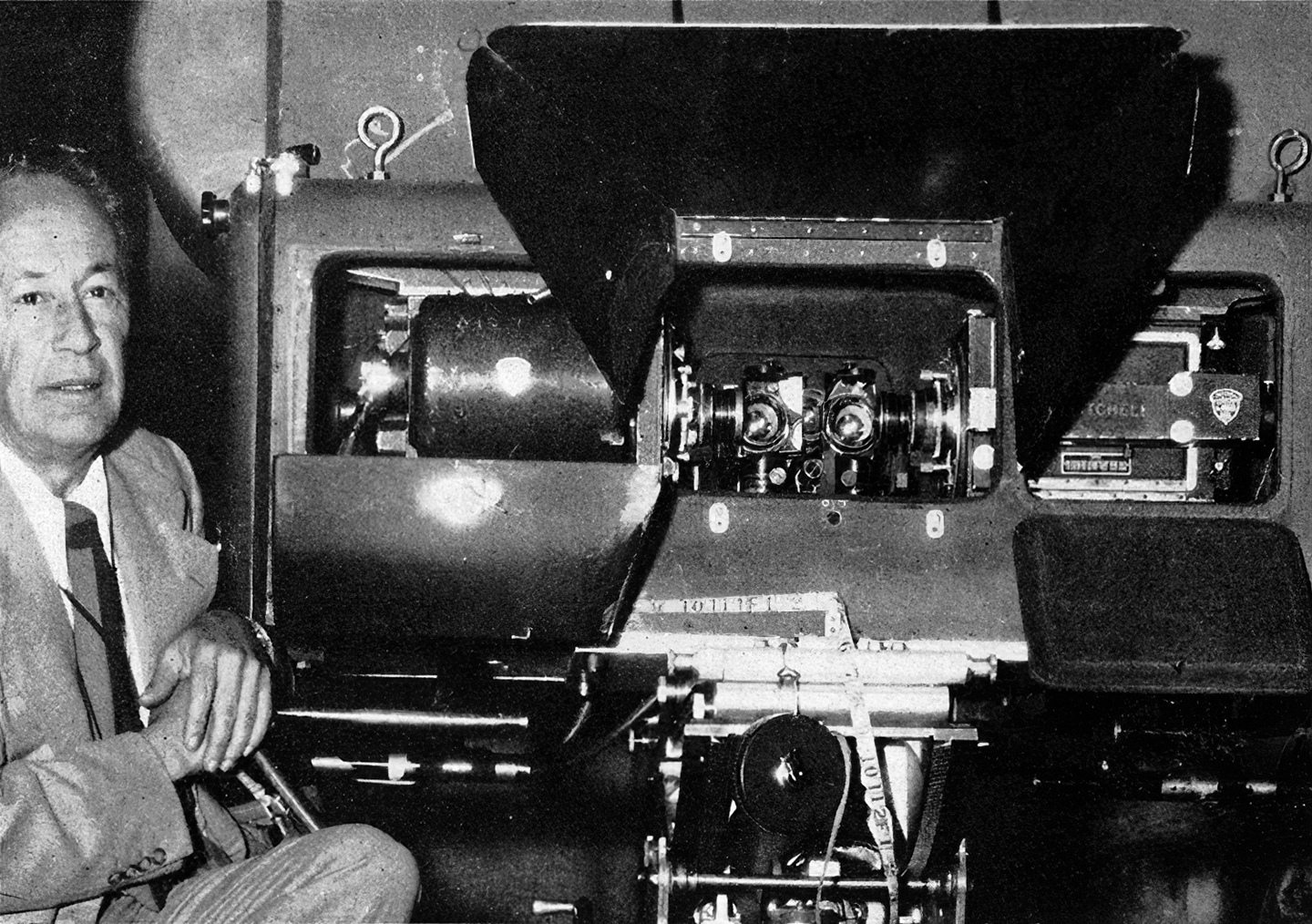

With only one day’s notice, J. Peverell Marley, ASC took over as director of photography on Warner Bros.’ 3-dimensional thriller House of Wax after cinematographer Bert Glennon [ASC] was forced to quit the picture because of illness. Marley jumped into the middle of his first 3-D assignment with literally no time to prepare. Also, it was his first experience with the new WarnerColor photographic process. It is a great tribute to this skilled craftsman that the general photographic quality is top-grade and that the 3-D effect is very striking, indeed.

From the critical technician’s point of view, the Natural Vision stereo effect in this film, while not perfect, is by far the finest to be shown publicly thus far. It is characterized by a smoothness and consistency not evident in [producer-director] Arch Oboler’s initial 3-D effort, Bwana Devil. The mechanics of the photography have been skillfully slanted to produce a very convincing, and at times very striking, illusion of depth. The stereo technique is ideally suited to the presentation of what is essentially a horror melodrama — but beyond that, Marley has used his camera to extract full dramatic effect from the action without relying too heavily on gimmicks.

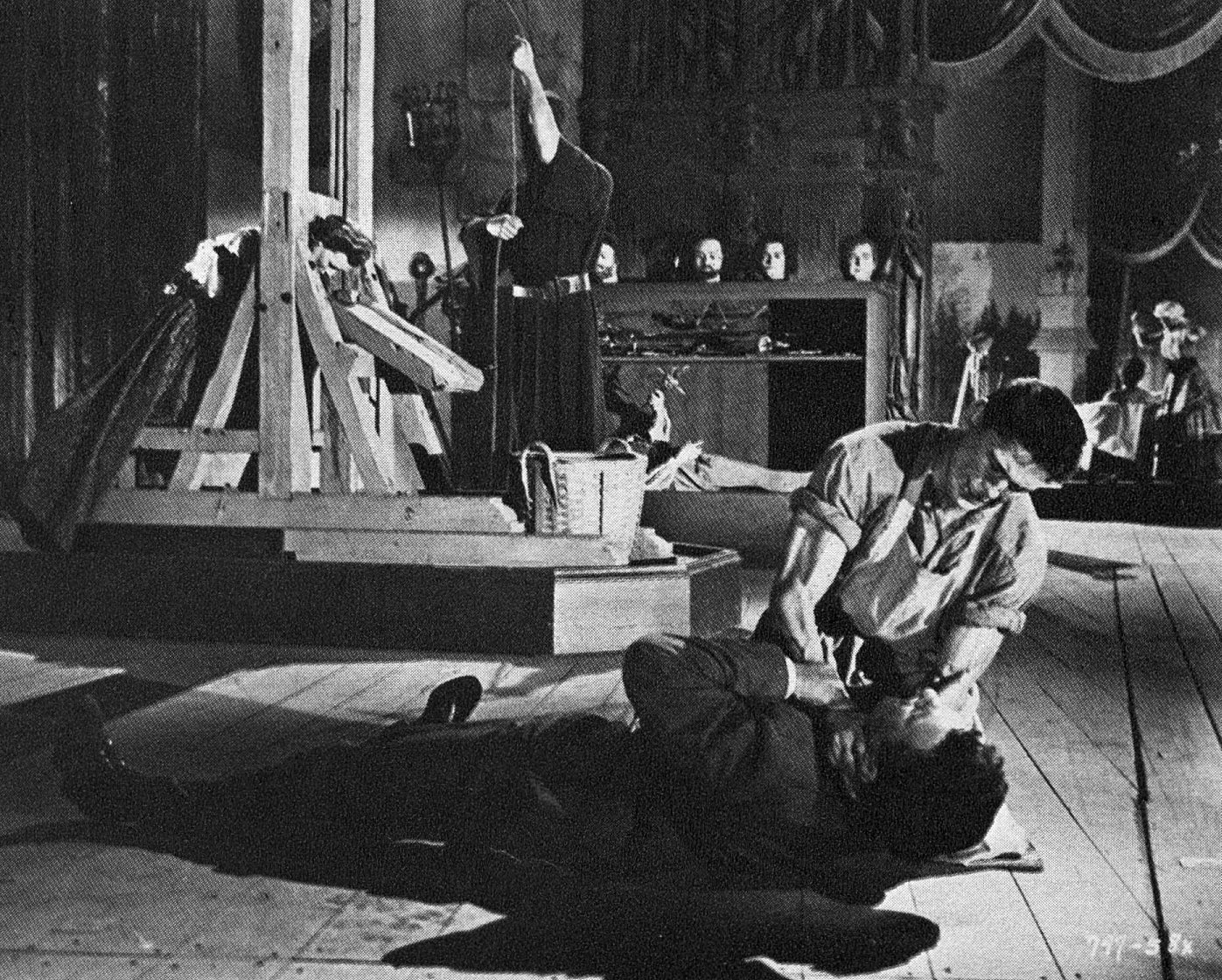

Of course, there are sequences in which, for example, a rubber ball on an elastic string is batted repeatedly into the faces of the audience, a scene in which a wax head (neatly lopped off by a guillotine) comes tumbling right into the viewers’ laps, and still other instances in which miscellaneous objects are pitched out of the frame of the screen and into the theatre. It is certain that the audience would have been disappointed had such jolting experiences not been included in a film of this type. In general, however, there is always a temptation to overuse effects of this sort. As Marley points out, 3-D photography (like any other good photographic process) exists not for its own sake, but solely to help tell a dramatic story in the most effective way possible.

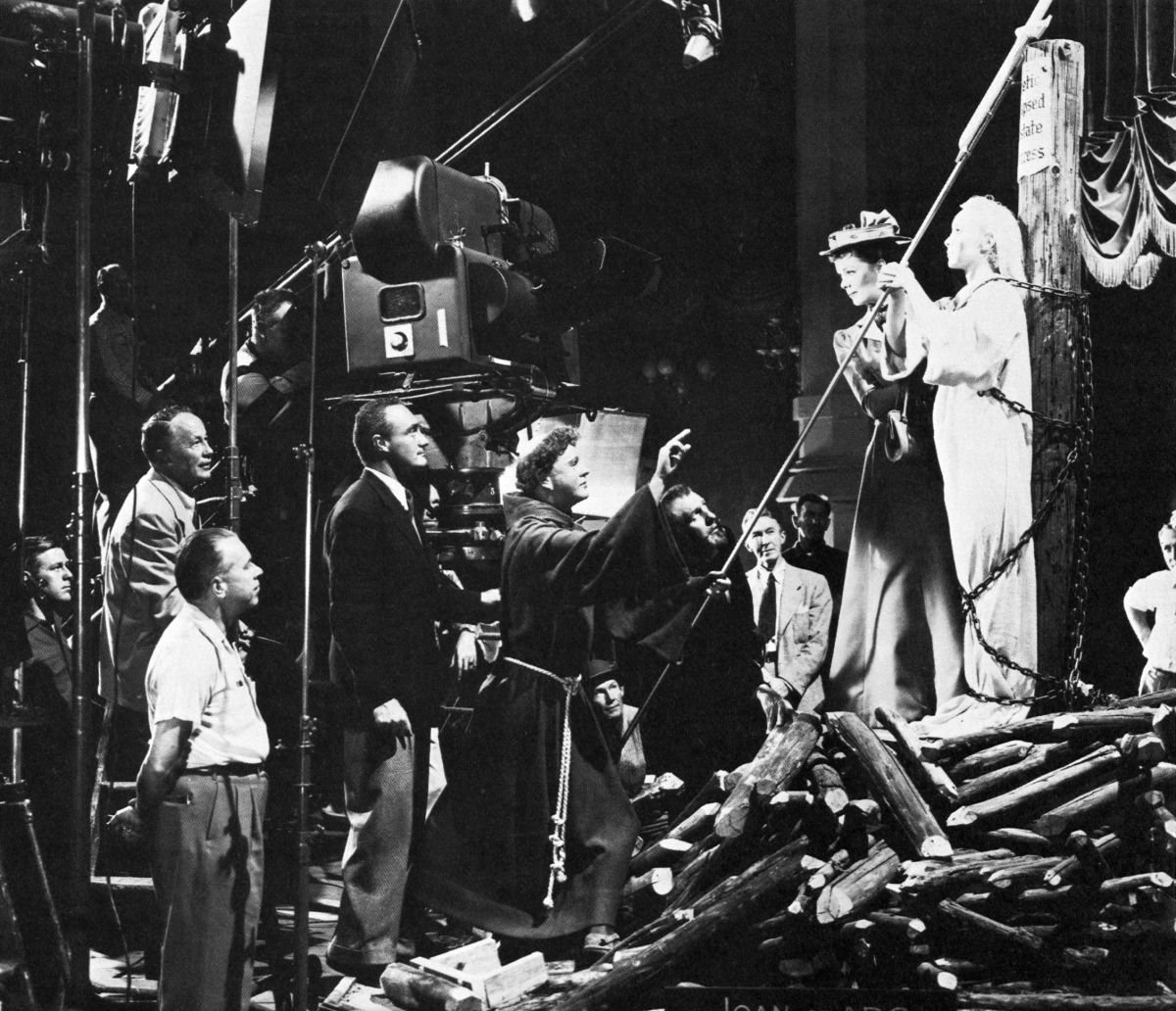

Briefly stated, House of Wax is the story of a sensitive sculptor whose wax museum is set afire by an unscrupulous partner to get the insurance money. Horribly disfigured in the resulting holocaust, and driven mad by his great loss, the sculptor becomes a monstrous murderer who stalks and kills people resembling historical figures so that he may dip their bodies in wax and place them on display. His detection and eventual destruction account for a bulk of the suspenseful action.

The most spectacular sequence in the picture, both dramatically and technically, is the fire that destroys the wax museum and its paraffin inhabitants. This situation reaches its climax in a roaring inferno of three-dimensional flame which seems to sweep right out of the screen and engulf the audience. Further horror is engendered by closeups of the all-too-lifelike waxen faces melting into scorched caricatures, glass eyes falling out of smoking sockets, etc.

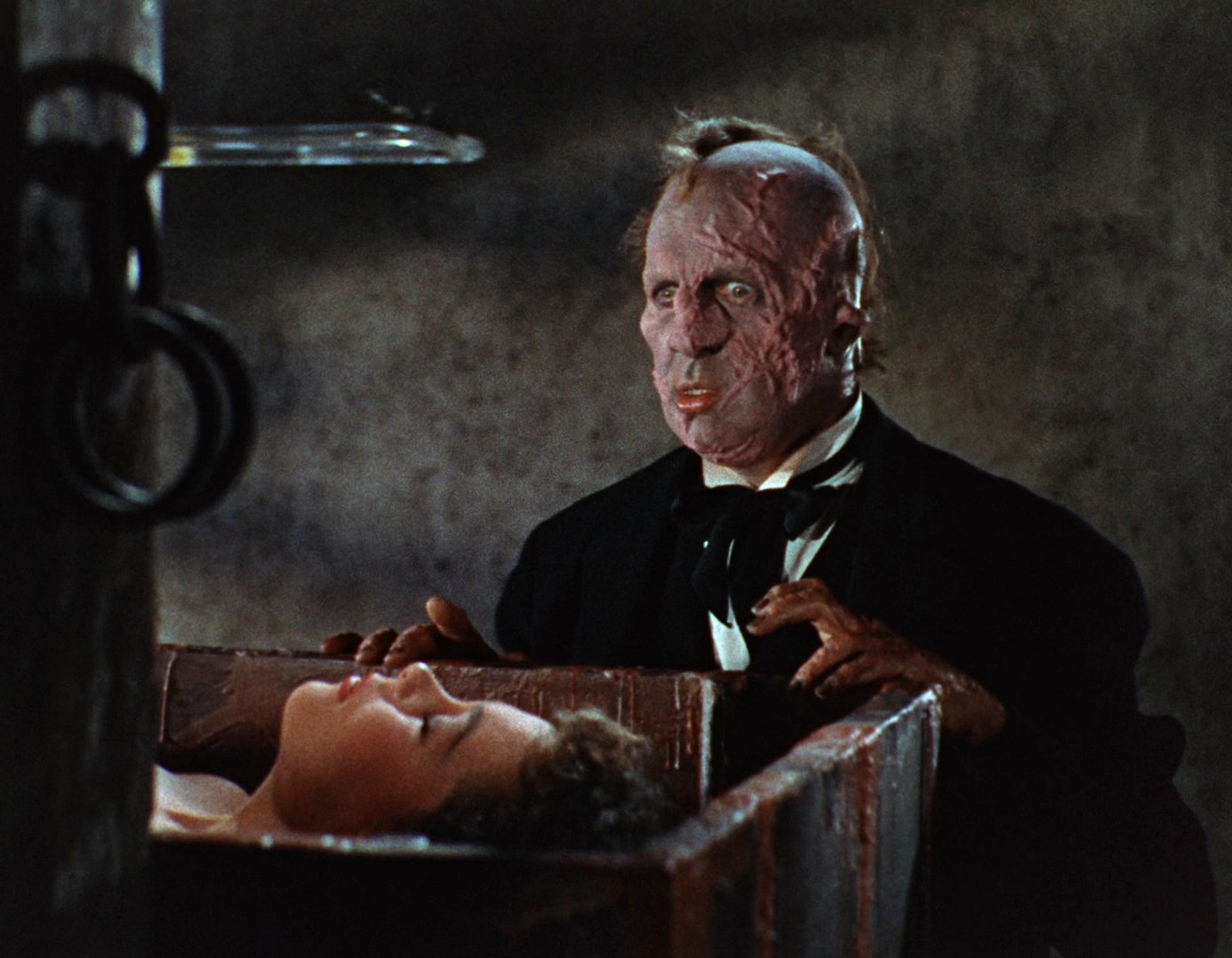

During shooting, this sequence provided one of the most violent pyrotechnic displays ever contrived by a Hollywood studio. Controlled by a corps of expert pyrotechnicians and special effects men, the fire raged for five full days on a giant sound stage. The only reported casualties, according to Warner’s publicity department, were the eyebrows and eyelashes of the leading man, neatly singed off by the flames, but just as neatly replaced by the make-up department. On the latter score, chief make-up artist Gordon Bau deserves special mention for creating the most horrible make-up ever seen in color. The deformed face he designed for the monster (light blue scar tissue strikingly filigreed with purple veins) is enough to produce a lasting trauma in any sensitive soul, and would have made the late Lon Chaney at his collodion worst look like a collar ad.

“Curiously enough, our main problem in 3-D filming is not so much mechanical as dramatic. By that, I mean that we must be — and are — constantly concerned about directing audience attention where we want it.”

— J. Peverell Marley, ASC

Pev Marley has found that with a few exceptions, camera movement is not restricted in 3-D filming, and he feels that any problems relating to fluid camera technique can be worked out by means of careful pre-planning. Zoom shots are not practical as yet. and there is the inevitable parallax problem when the camera moves past foreground objects, but boom shots with both horizontal and vertical movement work quite well. Marley discusses the photography of this picture with an ease amounting to understatement. “Curiously enough,’ he said, “our main problem in 3-D filming is not so much mechanical as dramatic. By that, I mean that we must be — and are — constantly concerned about directing audience attention where we want it. In three-dimensions, every element in the scene has a similar spatial value, and the eye tends to roam about and explore these elements much more than in a flat film. The problem is to corral the viewer’s attention and make him look at what you want him to look at — which is, of course, the dramatic focal point of what is going on in the scene. Any other single element, which juts out of the frame and steals audience attention away from where it ought to be, is bad and should be avoided.”

This is, of course, much more easily said than done, since the very objects which enhance the illusion of depth are also those which could easily distract the attention of the audience. For example, a tree limb framing the scene — traditionally used to lend depth to a flat scenic composition — can, because of its prominence in 3-D, distract the audience’s attention from the really important part of the scene.

In the filming of House of Wax this pitfall was generally avoided. But even so, in a couple of moving camera shots, foreground objects gliding by assumed such prominence that the eye of the viewer tended to remain with them rather than continuing on with the object of principal dramatic interest.

a camera angle for Warner's 3-D color production House of Wax, shot with

the Natural-Vision stereo camera. In foreground is operator Howard Schwartz.

Marley is of the opinion that the solution to this problem depends upon several factors. First, the staging of the action must be such that the eye will be directed to that which is most important. Second, lighting should be arranged (at least, up to a point) so that it will subdue that which is not important, and point up that which is. Third, the point of convergence of the twin lenses can be thrown to favor the area of principal interest, thus directing the audience's attention to the place where it should be.

Regarding modification of standard lighting techniques to fit 3-D, Marley feels that few radical changes are necessary. "It’s still a matter of the right light in the right place,” he says, but goes on to advise against lighting which is too contrasty, since this style of illumination, because of the innate parallax characteristics of the 3-D system, could produce an unpleasantly distracting effect.

On the other hand, while it is true that relatively flat lighting can be used successfully because the 3-D process itself lends depth to the figures, he still prefers well-rounded, richly modeled lighting. His work in House of Wax proves that this type of illumination, coupled with the mechanics of the system itself, produces the greatest possible illusion of depth. Such a result is especially effective in the climatic low-key sequences staged in the dimly-lighted, deserted wax museum. The strategic use of shadow and modeled light in this setting lends an atmosphere of impending horror that adds forcefully to the suspense of the action.

At present, the choice of lenses is somewhat restricted by the mechanics of the technical setup. A 40mm is about the widest angle lens that can be successfully used. This is due not so much to distortion, as one might expect, but rather to the fact that because the twin cameras cannot be mounted close enough together, a wider angle lens might show edges of the mirrors used prismatically to reflect the images. Marley feels that these mechanical limitations can and will be overcome so that lenses of 30mm or wider can be used. The standard 50mm remains the most popular lens for lending normal perspective to ordinary medium shots, while a 75mm or 100mm is considered ideal for close-ups.

The distance between the eyes of the average person is 2 ½". This is called “interocular distance.” In stereoscopy, the distance between lenses of the two cameras approximates the interocular distance of human vision, and is termed the “interaxial.” Thus, the twin lenses of the 3-D camera function similarly to two eyes to reproduce images in three-dimension.

“In ordinary shooting, we rigidly maintain the interaxial distance in our lens set-up,” Marley points out, “but there are times when, for special effect, we may vary it. In a long scenic shot, for example, distant objects tend to flatten out just as they would to the eye. However, by widening the interaxial distance, as represented by the lenses of the cameras, we actually force the perspective so that the distant landscape takes on depth.

The problem of parallax convergence is an ever-present one for the 3-D cameraman. If a slight miscalculation is made, the result may be a double image in the background of the scene. This is especially true in the closeups. For this reason. Marley suggests that action patterns be planned so that in the master or full shot principal actors be maneuvered close to a wall or other nearby object. In this way, a cut can be made to the closeup without encountering the parallax problem.

Marley estimates that a set-up in 3-D takes about 10% longer than required for a flat picture. However, since there are generally fewer cuts in the average 3-D film — and therefore fewer set-ups — shooting actually goes faster. As technicians become more familiar with the process, it is expected that even greater savings in shooting time can be affected.

“In 3-D you can tell where everything is in relation to everything else, just as in real life. I guess you could use a lot of high-flown words to describe stereo — but when you boil it right down, it’s just plain more impressive than a flat picture.”

Marley has found that with a few exceptions, camera movement is not restricted in 3-D filming, and he feels that any problems relating to fluid camera technique can be worked out by means of careful pre-planning. Zoom shots are not practical as yet. and there is the inevitable parallax problem when the camera moves past foreground objects, but boom shots with both horizontal and vertical movement work quite well.

Marley started his career as a director of photography with the filming of Cecil B. deMille’s classic King of Kings (1927) — a picture still regarded as a masterpiece of cinematography. It is an interesting coincidence that Marley (together with George Barnes, ASC) won the Hollywood Foreign Correspondents’ Association Golden Globe award this year [1953] for the color photography of still another de Mille production, The Greatest Show on Earth.

Marley has just completed his second 3-D film for Warner Bros., The Charge at Feather River. This is an outdoor epic in three-dimension in which the audience will catch a thrown knife between the eyes, and suffer similar 3-D fates. Marley is enthusiastic about the stereo technique as a story-telling medium, and cannot praise too highly Mr. M.L. Gunzburg, head of Natural Vision Corp., and his technicians who were so very helpful and cooperative in the filming of the two features.

Commenting on the third-dimensional trend, Marley says simply: “In 3-D you can tell where everything is in relation to everything else, just as in real life. I guess you could use a lot of high-flown words to describe stereo — but when you boil it right down, it’s just plain more impressive than a flat picture.”

“Futurewise,” according to Pev Marley’s reckoning, “3-D plus a fairly wide screen, plus stereophonic sound will be it!”

The Making of House of Wax

By Daniel L. Symmes

On November 26, 1952, a very low-budget film called Bwana Devil opened at the Hollywood Paramount theatre. While 3-D films had been made in the past, this one caught on and was an immediate box-office smash.

The major studios were in an all-time slump because of newborn television and low-grade films in the late 1940s. Needless to say, when an independent film makes money, studios look closely to see what they're missing. Jack Warner, like most studio moguls of the era, was a colorful and spontaneous personality. Rarely did he let an opportunity pass him by.

Director Andre de Toth (Springfield Rifle) had been interested in 3-D for some years and had even written an article on the subject for Variety in 1946.

The decision to have de Toth direct Warner's first 3-D was difficult to understand at first glance, for here was a director who could see with only one eye; not able to see 3-D at all! But, Jack Warner knew Andre de Toth, a perfectionist who understood 3-D, so the decision was easy.

It was the choice of story that took a bit of thinking. Why take chances? Go with a subject that's safe: Horror!

A little more thinking and someone remembered a 1933 Warner thriller called Mystery of the Wax Museum. It had the dubious distinction of being the last of the two-color Technicolor films, as three-strip was shortly perfected.

Based on a 1932 story outline by Charles Belden, screenwriters Don Mullaly and Carl Erickson wrote the story of a sculpter hideously scarred in a fire in his wax museum, who rebuilds the museum using actual human bodies covered with wax.

The original production starred Lionel Atwill and Fay Wray, and was directed by Michael Curtiz. Mystery met with considerable negative criticism from the press mainly because it tried to bridge mystery, suspense, and horror. Unfortunately, the time and place for such a combination were wrong. Subsequently, the film disappeared and was believed lost until a print surfaced and was shown (in two-color!) at Grauman's Chinese Theatre as a special presentation of the 1971 Filmex.

Spending (and having) little time, Crane Wilbur took the original script, changed a few characters and the era, retained much of the original dialog, and came up with The Wax Works. Production began on January 19, 1953, filming with the Natural Vision (dual-camera) system. Production was completed in a startling 28 days, wrapping on February 20.

of Charles Buchinsky (later known as Charles Bronson).

An interesting cast was assembled by de Toth, with Vincent Price, Paul Picerni as the young “hero,” Phyllis Kirk as the ingenue; Frank Lovejoy, just making a name for himself; Dabbs Greer for comedy relief; and Charles Buchinsky. Who? Most now know him as Charles Bronson, in his first spotlight role.

Andre de Toth says of the cast: “Bronson said, ‘Why are you picking me? Because of my muscles?’ His was a mute part. I said, ‘I’m taking you because you’re a good actor.’ He could have been one of the greatest stars of all time. He has enough strength and at the time he had a sense of humor, almost like Clint Eastwood... but Buchinsky screwed himself up. He wants to be the lead, instead of having the talent exposed. In House of Wax, you could see him thinking, even with every little gesture. One day I hope I’ll have a part for him where he'll be recognized as a talent, not only muscles.

“I used Dabbs Greer in a couple of pictures. He thinks, he follows, and he doesn’t want to be a star. Most character actors want to be upfront and chew the scenery, but not him. The problem I had with Phyllis Kirk was that she thought low of herself. Carolyn Jones was ‘sexy,’ and she felt she wasn’t. It affected her all through the picture. I tried to bring her out... ask Vincent Price. She hated me, but I respect her and think she’s a terrific actress.

“Vincent was absolutely superb. Never missed a minute. A real pro. I have great respect for the man as a human being and an actor.”

— director Andre de Toth

“Vincent was absolutely superb. Never missed a minute. A real pro. I have great respect for the man as a human being and an actor. I would like to work with him. I don’t think he’s even scratched the surface.”

Andre de Toth’s theory of 3-D film is conservative if a single word is adequate. He states: “It can combine all the forces, all the possibilities, of the motion picture and the theatre. It’s not to throw things at you but to involve the audience... Instead of ‘showing’ it [story] to an audience, make them part of it; the feeling, the expeience.”

There are numerous places in HoW where de Toth could have gone gimmick, but he didn't and a much more satisfying film was the result.

He did bend a bit, such as with the barker in front of the newly opened museum. Armed with two paddleballs, Reggie Rymal practically knocks our heads off.

More in keeping with de Toth’s idea is a scene toward the end of the picture where Picerni is trying to save Kirk. Bronson pops up into view from below camera, producing an amazing effect of seeming to have jumped up on the screen from the front row.

Photography was started under the direction of Bert Glennon [ASC], who became ill with the flu during the first week of shooting. Peverell Marley took over with Natural Vision’s specially trained operator Lothrop Worth, assisted by Howard Schwartz (also from Natural Vision). Both have since become noted directors of photography.

Eastmancolor “tripak” was introduced a couple of years earlier, reducing the industry’s reliance on 3-strip Technicolor. Warner Bros. set up their own lab and, using Eastmancolor negative, introduced “WarnerColor.” As originally seen, the color quality was very good in HoW, adding substantially to the 3-D. Unfortunately, either because of processing techniques or poor storage, the original negatives of many WarnerColor films have tremendous color shifts today.

Convergence and vertical alignment were excellent overall; a far cry from today’s supposed improved productions. There is not one shot (including close-ups) that causes eyestrain. Again, it was de Toth’s observations and understanding of 3-D that made a significant difference. I must add that the studio system controlled photographic integrity in those days. The equipment was made to work right with a “do it right or don’t do it” attitude. Today, it’s every man for himself when using some current 3-D equipment.

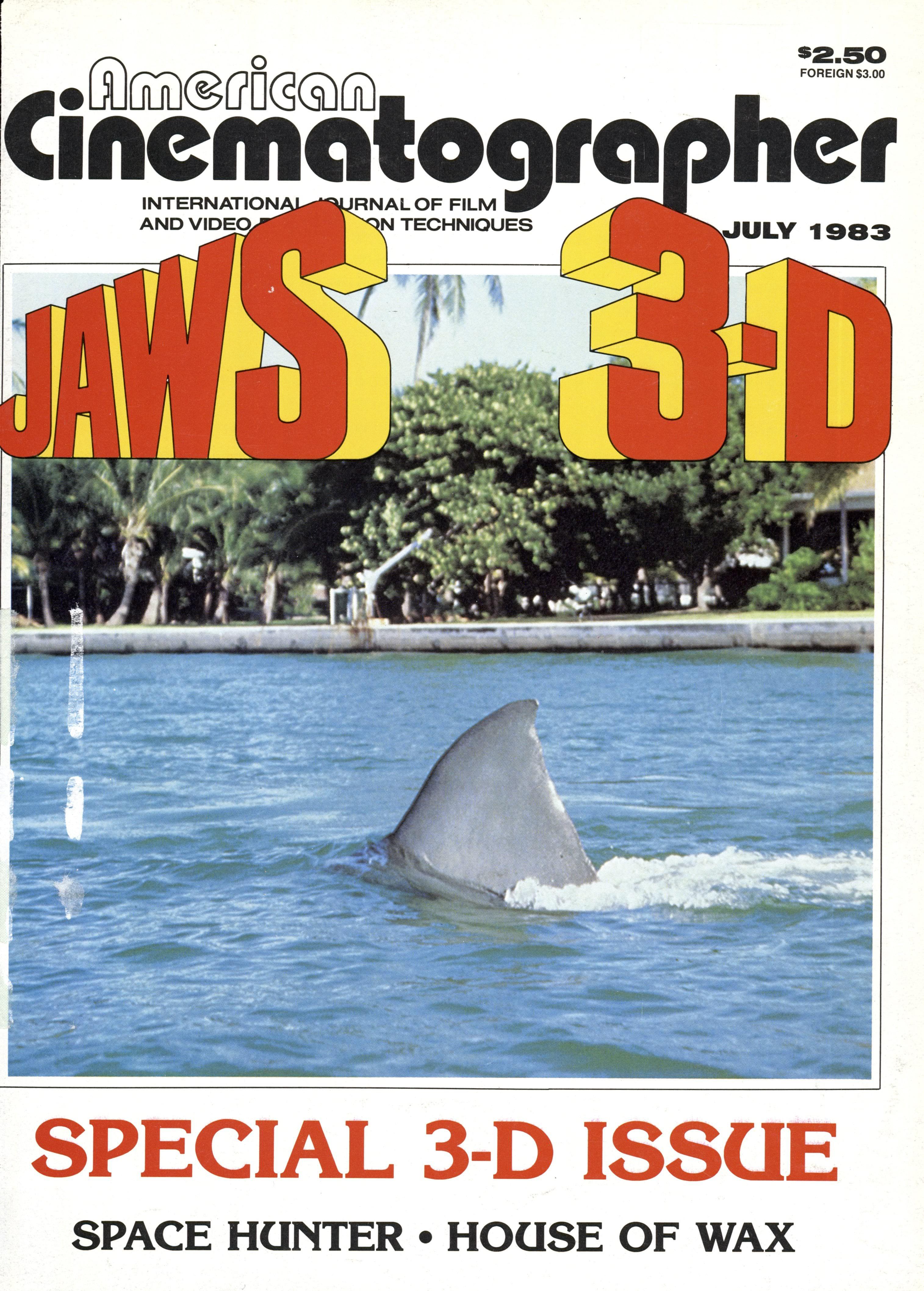

It has been observed by many that things looked rounder in HoW than today’s product. That’s easy to explain. Because of design considerations, the Natural Vision system was limited to a minimum interaxial (lens separation) of 3.5". Most 3-D systems are about 2.5". The extra inch “sees” around subjects more, producing the roundness. (See other articles in the July '83 issue of AC for more on this subject).

Set design was simple and straightforward. The concept of the wax museum at the turn of the century was well-styled for 3-D, effectively laid out, using a good amount of stage space. The wax figures were created by two Burbank artists, Mrs. Katharine Stubergh and her daughter. At the time of the film's release, Mrs. Stubergh offered to make wax figures of anyone for only $500.

The most memorable sequence occurred in the beginning: the burning of the museum. According to de Toth, the scene almost became too real. During the fire, a hole was burned in the roof of the stage and firemen were spraying water on the roof (and sets) while the cameras were rolling. Since the wax figures could not be readily replaced, once the fire was started they had to keep filming. They began with spot fires; one figure would begin to burn and would be shot, another would be ignited and filmed, with three bulky Natural Vision camera units being pulled around on huge dollies, trying not to run into each other in a traffic jam.

The only casualties of this adventure were the eyebrows of Vincent Price, which came away singed, and the stage roof. If one watches carefully, the blueish-daylight can be seen coming from above during some shots.

Price’s makeup for the role, which is grotesque even by today’s standards, took, on average, three hours to apply and was very uncomfortable as it required his ears to be bent and twisted, his nostrils twisted and flared, special dentures, and the requisite facial scars. The grim visage was the creation of Gordon Bau, under contract to Warner’s and one of the key makeup artists in Hollywood.

The music in House of Wax was composed by David Buttolph, with orchestration by Maurice de Packh. Particularly eerie, the score included a “phantom's theme” which crept in at odd times, anticipating the horror about to occur.

Not only was HoW the first major 3-D film, but it was also the first to use stereo (WarnerPhonic) sound. Three tracks of sound were on magnetic film (for behind the screen), with a fourth surround track (optical) on the right-eye print (a composite mono track was on the left print).

Finally, even though it was shot in a 1.33:1 aspect ratio, it was often cropped to 1.66:1 in projection for a semi-wide screen look.

Although HoW premiered in New York on April 10, (at 8:00 am!), the biggest event occurred in Los Angeles. At one minute past midnight April 16, the Hollywood and Downtown LA Paramount theatres began a “Premathon.” For the next 24 hours, there was a special showing for just about everyone: “2 am Swing Shifters Premiere”; “8 am Career Girls Premiere”; “10 am House Wives Jamboree,” etc.

Contests: the first 25 married couples got their marriage license fees refunded. USC cinema and drama students got credits for seeing the film. Over 200 film and TV personalities showed up, particularly at the 8 pm show. The L.A. City Council officially decreed April 17 as “3-D Day.” Thirty special police officers and 12 selected guards from Warner Bros. were needed for crowd control.

As for figures, the first week grossed $58,200 at the downtown Paramount, and $37,230 at the Hollywood; good figures by today’s standards, even more so when one considers the average admission was about $1.25!

With all that’s been said and done, 3-D hasn’t really improved since House of Wax. True, the equipment is smaller and lighter, but the artistic and technical aspects of 3-D today have yet to match those set down exactly 30 years ago.

And 30 years after this retrospective article was published, and the film hit 60, people were still talking about it, including such filmmakers as Martin Scorsese, Joe Dante, Wes Craven and Rick Baker: