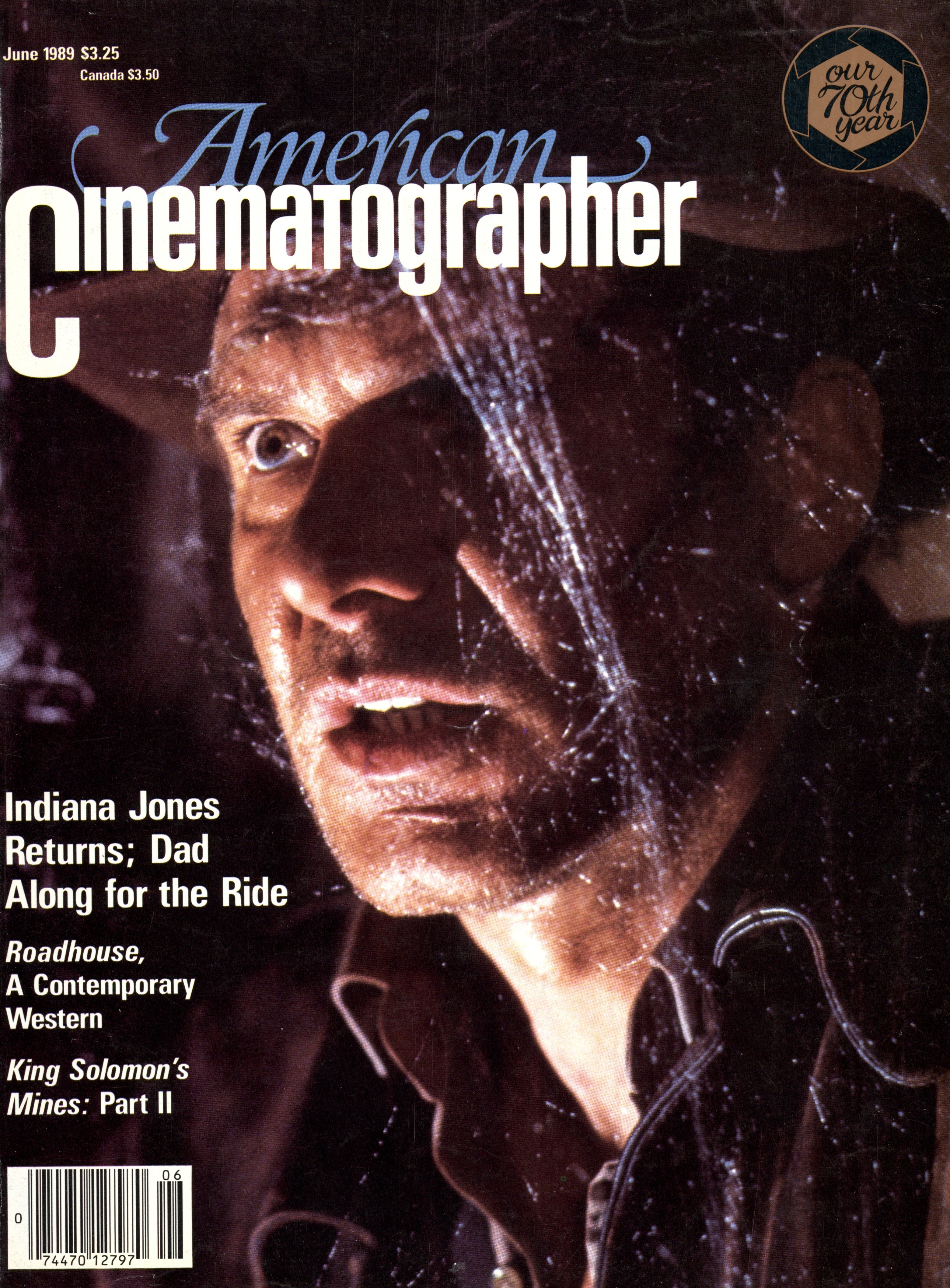

Douglas Slocombe on Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade

The cinematographer details — as much as his memory will allow — shooting his third and final Raiders picture.

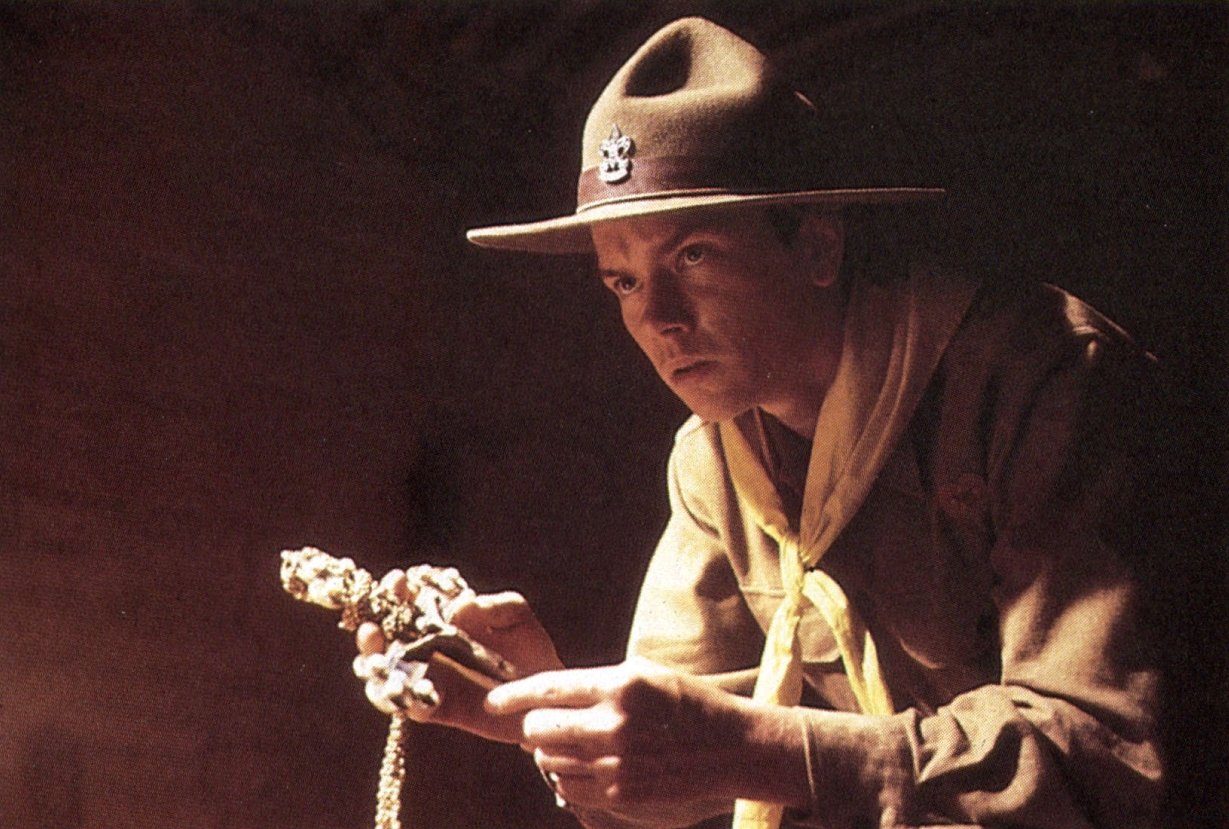

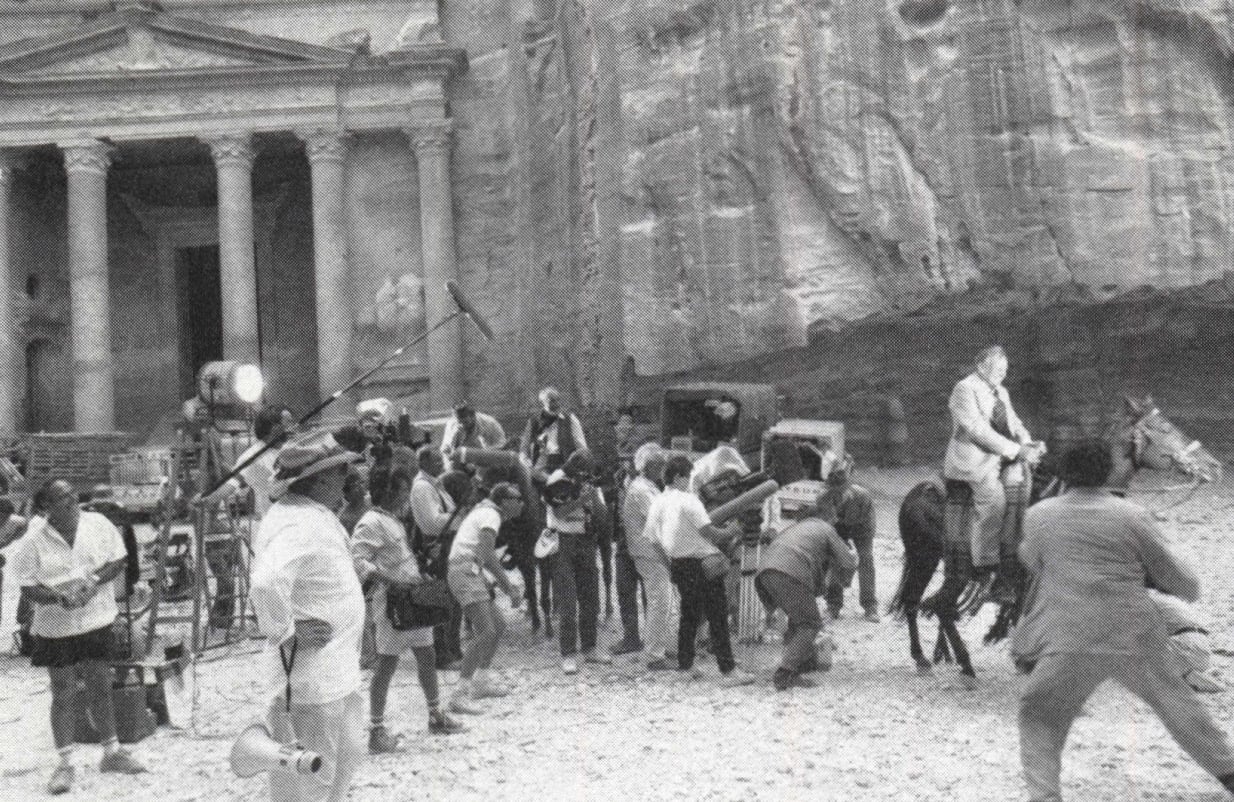

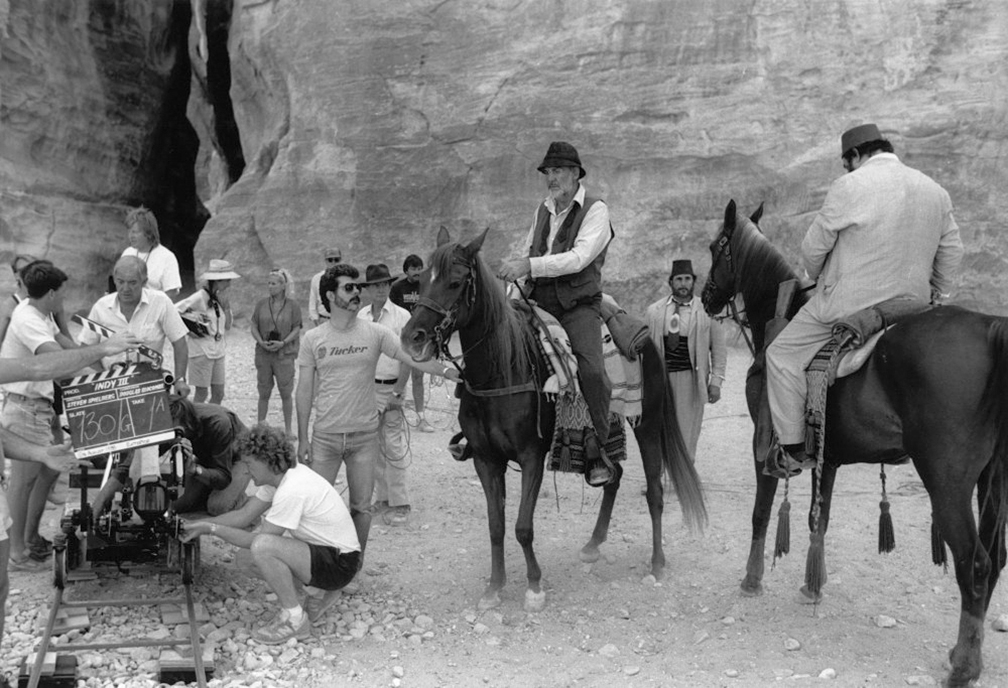

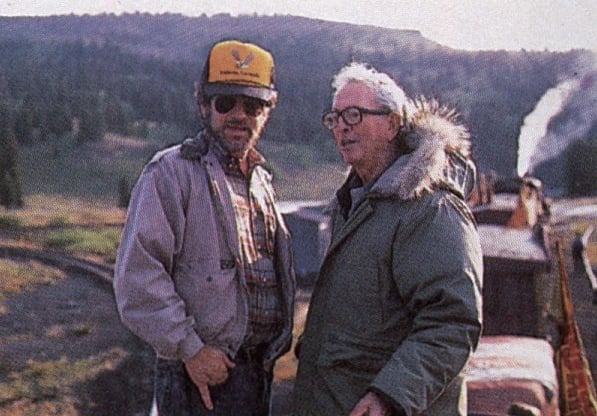

Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade reunites a most talented and successful group of filmmakers, including George Lucas, Steven Spielberg, Frank Marshall, Robert Watts, and, germane to our purposes, cinematographer Douglas Slocombe, BSC. This team, along with Harrison Ford, was also the creative drive behind the first two installments of the Indiana Jones saga, which rank among the most inventive and successful films of all time. This time around, Ford will be joined on the screen by Sean Connery (as his father), who knows a thing or two himself about portraying adventurous movie heroes.

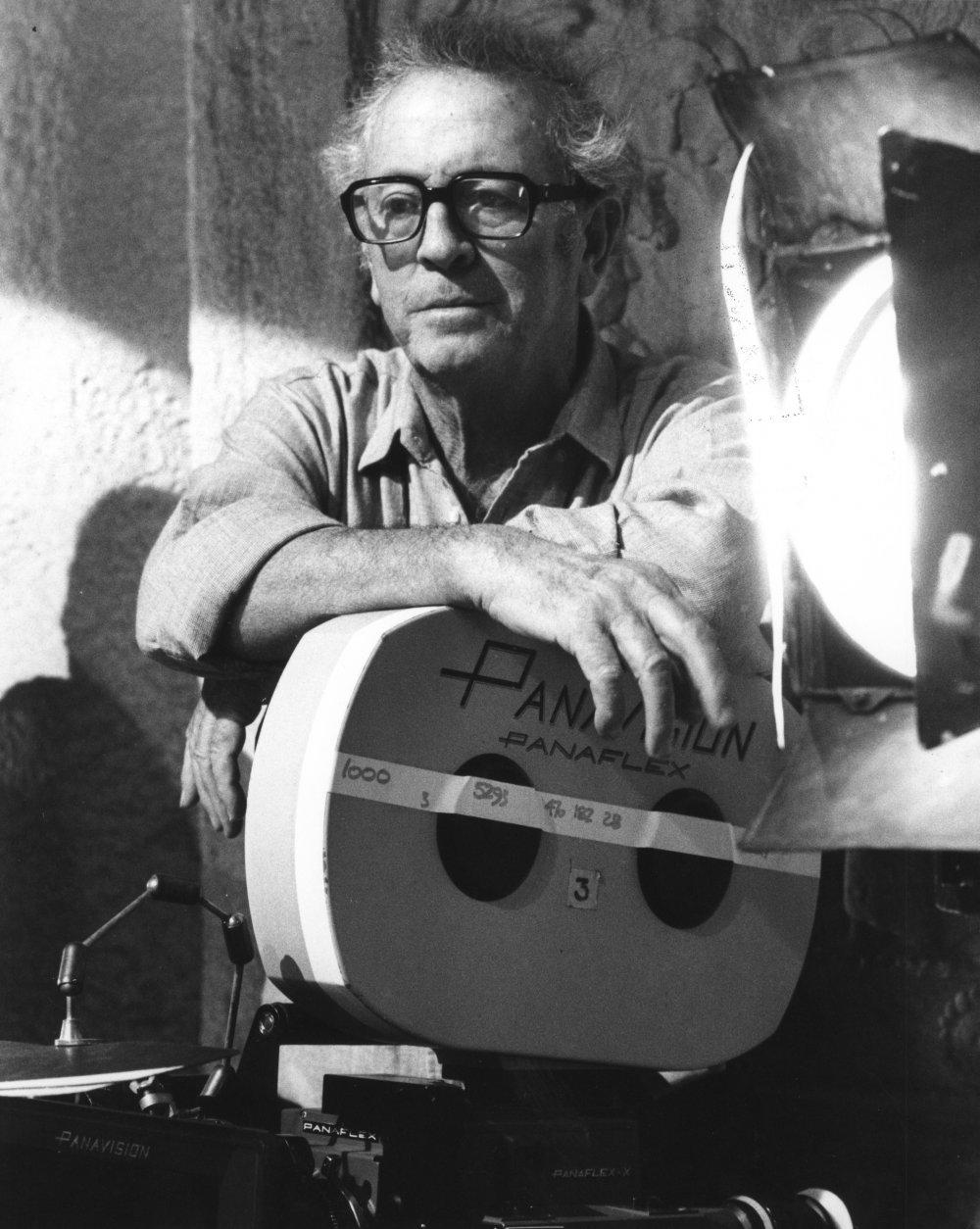

Slocombe's impressive body of work spans six decades. A charming white-haired man with a proper British accent, he began his professional cinematography career with a “baptism of fire" in 1939 Poland that rivals even an Indiana Jones adventure. But more on that later.

Slocombe's association with Steven Spielberg started with a pickup sequence of Close Encounters of the Third Kind. Pleased with the results, Spielberg promised to hire Slocombe for an entire film, when the time came. He kept his word by offering Slocombe Raiders of the Lost Ark. “He's a tremendously loyal man," says Slocombe, “and happily his loyalty extended to the second and third Raiders pictures.

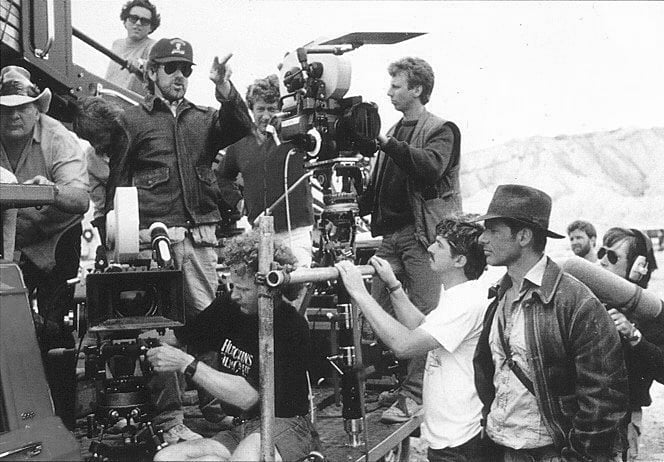

“One of the intriguing things about working on a picture like this is that you have to go along the same way the film does — at breakneck pace.”

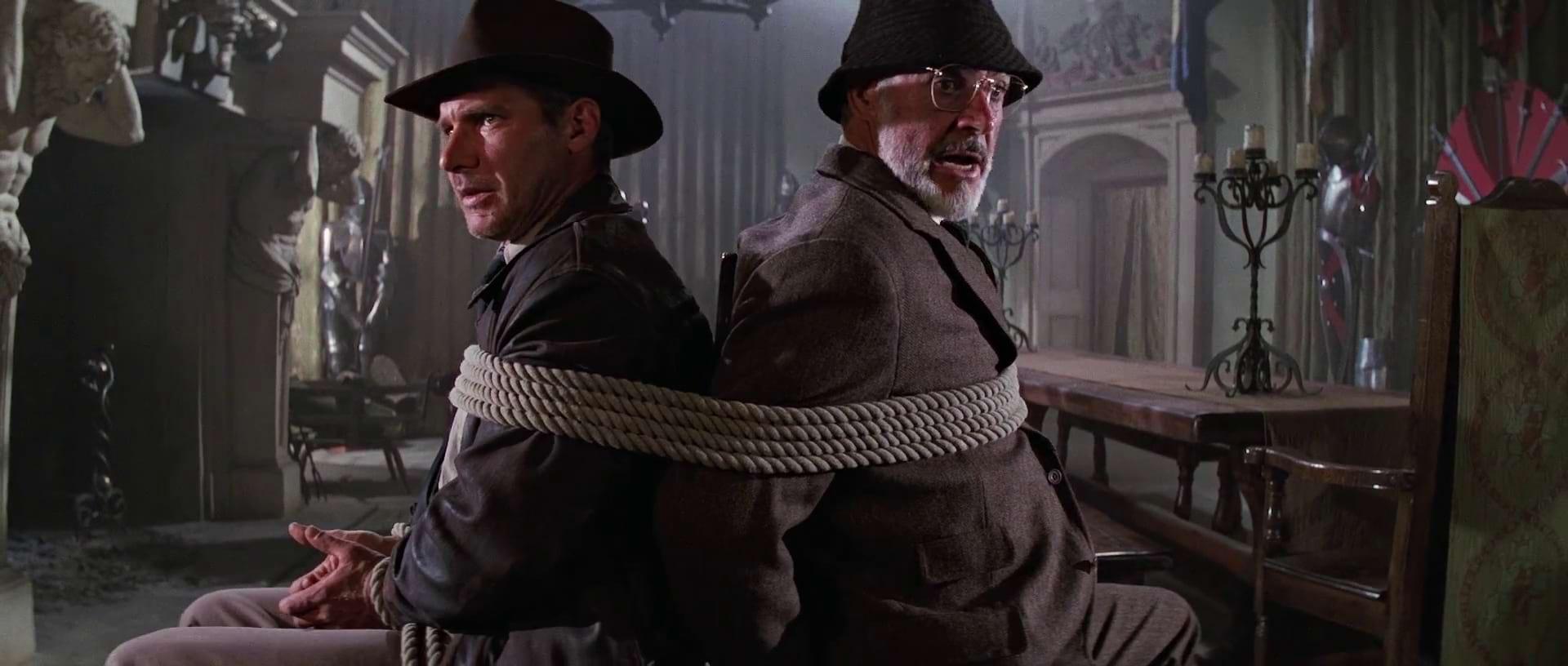

“I think that the third may be the best of them all," he continues. “It's a fascinating story. In fact, this one's probably even more inventive than the other two. Adding Sean Connery to the story as Indy's father was an intriguing idea. It was brave and generous of Harrison to accept another major male star on the same billing — but it's very typical of Harrison to see nothing wrong with that. As it turns out, it's a wonderful relationship. I think they genuinely admire each other and enjoyed each other's company, and there's a chemistry on the screen that does add to the picture. “

“It's very exciting to hear that theme music again — it picks you up and keeps you going. Funny enough, the picture does exactly that. It's like a plane that rushes down the runway and then takes off. You get a feeling of increased speed, of relentless movement, and it's absolutely non-stop until the end. The point is that before you can analyze one situation, you're off into another.

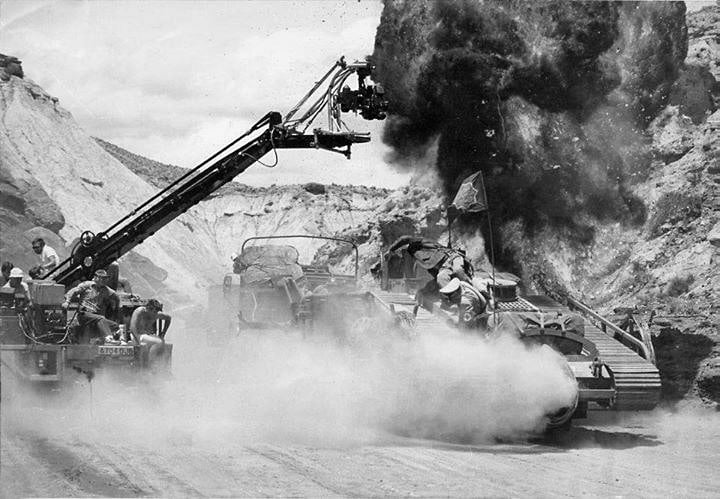

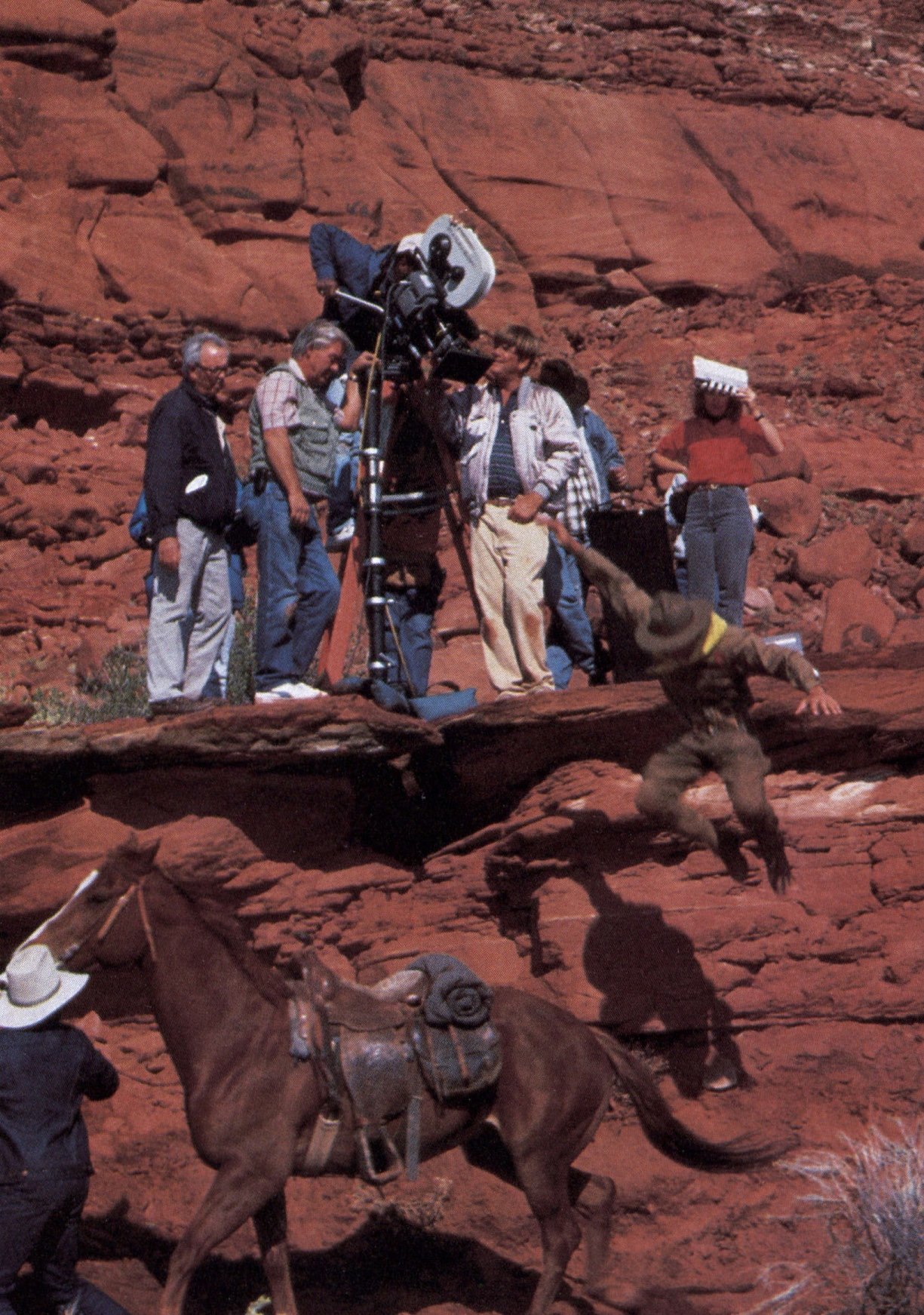

“From my point of view, one of the intriguing things about working on a picture like this is that you have to go along the same way the film does — at breakneck pace. I would guess that the average film is told in something like 300 to 500 setups. But all three of the Indiana Jones films have to run to at least 1,500 setups, probably close to 2,000. It's an incredibly expensive exercise, so there are great pressures to keep to the schedule, which is tight to begin with. I rarely had time to sit back and put finishing touches to a scene. The point is to tell the story as simply as possible. I can't remember the number of times when I was saying a few words to an electrician about where I wanted a lamp, or some detail I wanted to fix, and I would hear Steven shout, 'Turnover!'. So, at that point, I would know my time was up,'' Slocombe chuckles.

“Steven likes to plan everything very carefully, and for good reason. Every shot in all his pictures involves so many departments, with an awful lot of special effects. A lot of things have to happen in a very short time and really cannot go wrong. Obviously, these departments need to know exactly what's going to happen where and when so they have enough time to prepare all these things.

“Having said that, I would add that Steven doesn't stick completely to the storyboards and the planned setups. He's very inventive on the floor, too. He likes to have that freedom, and if he can find a better way of doing something, he will use it. For the average sort of 'boy loves girl' story, a non-action story that takes place largely just in rooms and simple exterior settings, I don't think that there's any reason that a director should be bound to pre-conceived setups. But for this type of picture, I think it's essential."

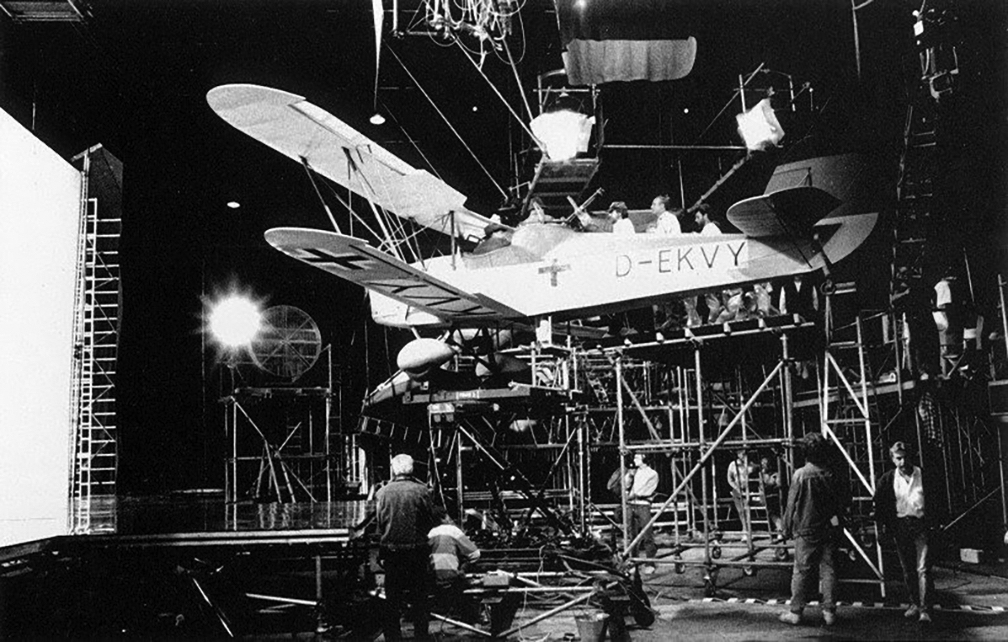

Photographically, of course, Slocombe approached Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade as a continuation of the first two Raiders pictures. “The three pictures have become one picture," he says. “All three are anamorphic, and all three have a lot of showings in 70mm. The people at DeLuxe told me that the first two films, and the bookings they have for this one, required a larger number of 70mm prints than they have ever needed. So one has to constantly bear that in mind, especially with the amount of special effects. It has to be fairly sharp and clean, so it will blow up well and look good in any type of theater in the country.

“Another consideration with the Raiders pictures, and any anamorphic film, is the fact that it will eventually be shown on television, and you'll see exactly half the picture. You can try to keep the action in the middle when you're shooting, but on a really complicated action picture, it isn't always possible to do that. So the scanners and panners will have to do their work. But I've seen Raiders of the Lost Ark and Temple of Doom on the box, and I think they work. Of course, you lose a lot of the impact — I always think the big ball rolling after Harrison loses all its impact on the box — but, in general, I think they hold up quite nicely.

“In regards to 70mm, to a certain extent, one has to consider filling the frame. But actually, the bigger the screen, the more care one needs to take in really directing the eye to the right bit of action. Otherwise, people can get lost, especially when the action is very quick. In a lot of pictures, you have a few seconds to see things rather than minutes. So the eye must be directed very strongly to the correct part of the screen.

“A long time ago, you had to leave something on the screen for a good bit for people to grasp it. Now, with the visual experience of moviegoers, and image can actually have an impact in quite literally a few frames. It's amazing what the retina and the mind will accept and retain after just a few frames. Also, the continuity can make great jumps, with no need for comings and goings, without losing the audience."

Indeed, from that perspective, if one of the Raiders pictures was shown in a theater 50 years ago, the audience would probably be completely confused, and stagger out of the theater as though they had been hit on the head.

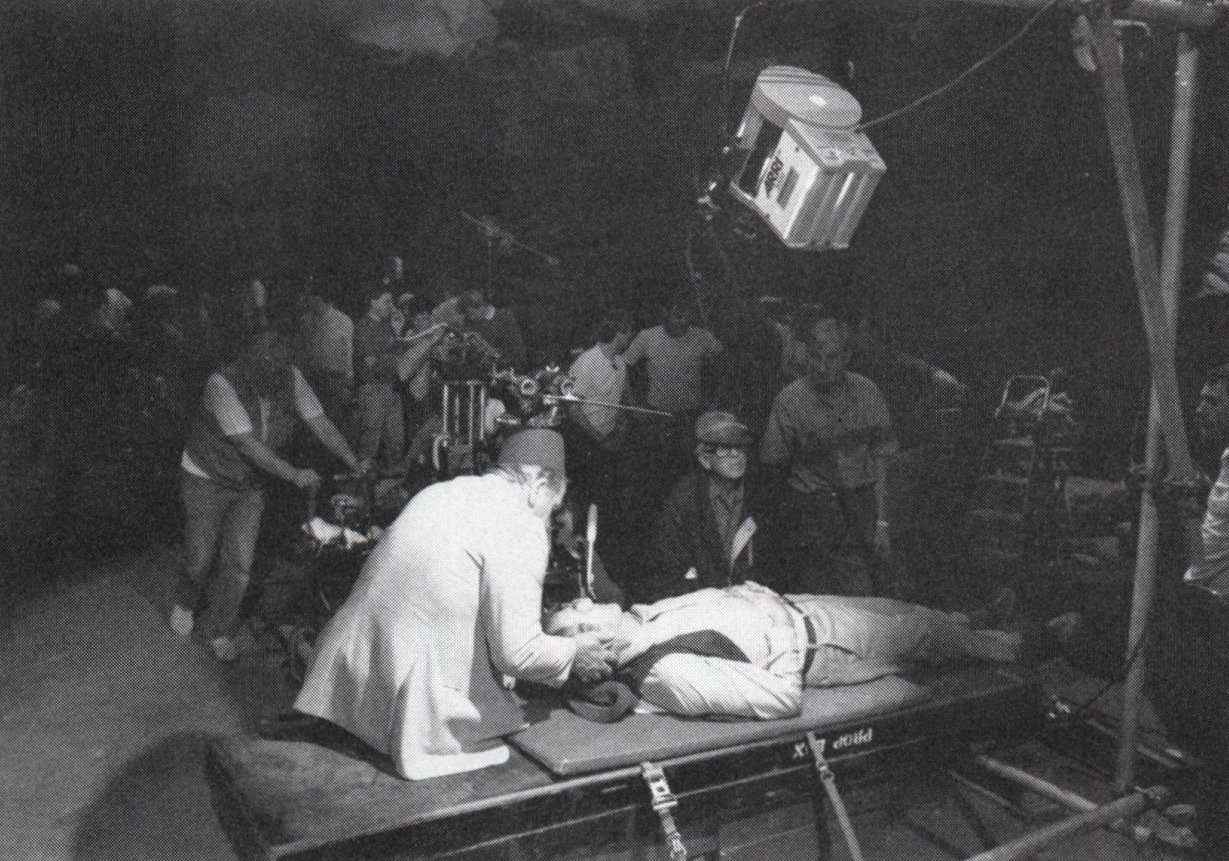

Slocombe cites the large sets as another reason for care in directing the eye. “The sets seem to get bigger and bigger these days," he says, “and particularly Steven Spielberg's sets — they're absolutely enormous. I always felt that the fellow who built the coliseum in Rome must have been an ancestor of Steven's. Anyway, on a larger set, I've found that if you were to take the set as a whole, you would think at least a hundred lamps would be needed to light it. You could spend hours lighting the whole thing, without really getting the essence of it. Actually, it's very easy to light a set in which you're lighting all the walls and corners, and lighting the action in the middle — but it's also very easy to end up with nothing.

“In this situation, a lesson I learned from my days as a journalist is applicable: to try to focus in on the center of the story point, on the essence of it. You have to ask, 'what could possibly give an impact here?'. For example, it might be better to throw the whole set away, or not light any part of it, and use one long shaft of light to give the impression of a huge space. By the way, this is also the approach of the cartoonist. You want to highlight the part of the scene where something dramatic is happening.

"One of the terrible dangers of shooting a picture of this scale presents itself at the rushes. All studios have projection theaters with screens that are far too small. I know there's a space problem, especially in England because it's a tiny country and there's no room to put anything anyway. But it's very dangerous, really, because one sees things at the wrong scale, both dramatically and technically. It's hard to tell what it will look like blown up, and being too close to the screen can be overwhelming.

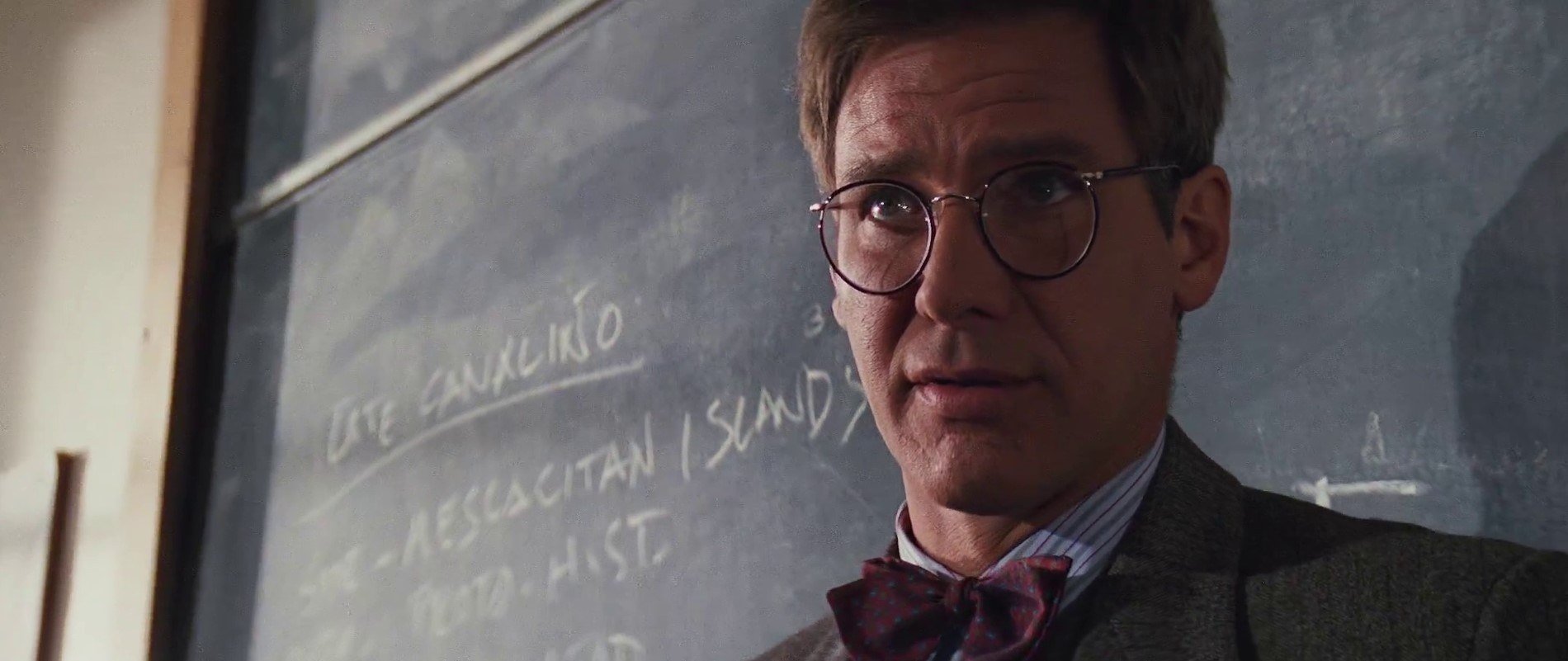

"One photographic difference between this film and the first two is the increased use of the close-up. In addition to the usual big wide shots, there's a lot of close-up work. We used the tight shot to momentarily concentrate the action and attention more often than in the past

"As far as lighting goes, I never try to be kind to Harrison. I think he has a wonderful head, with such expressive features, that I like to play them for all they're worth. I like to keep a sort of rugged look, in keeping with the character he plays. He can take strong lighting, so I make no excuses for him. In the scenes where he plays the mild-mannered alter ego, I do shoot him differently. I wouldn't say that I soften him, but I don't harden him.

"I've worked with Sean Connery before on a number of pictures, [including Never Say Never Again] and he's a very nice man to work with — a very interesting character. He also has an expressive face, so I don't flatter him, either. I'm inclined to light the dramatic look and take advantage of the character in a face, rather than try to hide it. For women, it's different. It's gallantry, I suppose, that forces one to behave a little more carefully," he chuckles.

Indicative of Slocombe's vast experience and knowledge in the art of photography is his ability to light without a meter. "I used to use a light meter — I used one for years," he says. "There was a whole series of them when I was working at Ealing Studios. In those days, meters were in very primitive forms, progressing through different types and finishing off with the enormous box that one used for the three-strip Technicolor process.

"Through the years, I found that, as schedules got tighter and tighter, I had less and less time to light a set. I found myself not checking the meter until I had finished the set completely and decided on the proper stop. Then at the end, I would hold the meter out, and it would usually say exactly what I thought it should. If it didn't, I wouldn't believe it, or I would hold in such a way as to make it say my stop," he laughs. "After a time, I decided that this was ridiculous and stopped using it entirely, and stopped even bringing it along. I don't suppose I've used one for a good 15 years now. Julia, The Great Gatsby, and the Raiders pictures were all shot without a meter, not for a single shot. I just got used to using my eyes, instead of relying on a box.

"On any picture like the Raiders films, one works very closely with the special effects people," he continues. All those things need to be done in a very collaborative way. For instance, in the first Raiders, there's a scene with a red-hot poker. Their idea was luminous paint on the tip of the poker, whereas I asked for special poker to be made with a quartz lamp inside, so as to give you the full, very strong light effect. So all along, I ask them what they want, and vice versa. The most important thing is to have time beforehand to discuss these things.

"All three pictures were shot using Kodak stock, both fast and slow. The first film we used 93, the second, 94, and this one 95. So it shows you the number of years between them, and the development of the new stocks. This new stock is a fine grain, and one of the reasons for choosing it was the amount of optical work to be done. Since it is a T-grain, the people at ILM were very happy to go along with it. We did use the 47 for some things — obviously in very strong light situations like desert scenes. But all the interiors, without exception, were done with 95. We thought it was a very sharp, clean film on the small screen — almost too clean. I think Steven felt at times that it was a bit too clinical. You could see every line and dot. But I got along well with it, and most times it will be on the big screen.

"For the camera, we used Panavision," says Slocombe. "I'm a great believer in Panavision, what I like about it particularly is that everything works and goes together. You never need an adapter, and you never have trouble getting an extra filter on the camera. The other thing is that we needed God knows how many cameras, all with video assist — which we found very convenient on this picture — a very large number of lenses, enough filters to go around to all the cameras, and only Panavision can really give you that kind of backup. They've never let me down yet."

When asked to reveal some of the secrets to his success, Slocombe points out that his advantage is not in what he remembers, but in what he forgets. "My memory has always been hopeless," he says. "It's probably a good thing I left journalism, because once I walked away from a story, I very rarely remembered what a person said, or even what his name was. But I must say that a good memory is not really needed for a cameraman; in fact, it can be detrimental. Some cameramen can fall back on the way they lit a certain type of set several pictures back, and they can sort of relax and do it quite easily. A typical example would be a courtroom. The number of times every cameraman in the world must have shot a courtroom... But I can never remember how I did it before. So every time I come on the set, it's as if I'm seeing something completely new, and I scratch my head and wonder how I'm going to do it. My lack of memory is allied with the fact that most everything I've had to do in films, I've had to sort of work out for myself."

Slocombe's self-training is partially a result of the roundabout way he came to be a cameraman. He firmly believes that everything a person does or takes an interest in during life contributes in some way or “stands you in good stead" toward an eventual level of achievement in a chosen field. Slocombe's route to cinematographer is a fascinating story.

“I mentioned that I was a journalist, and I think that being a journalist teaches a person to use one's eyes and ears, and also to pick up the essentials of a story, and to figure out what it is that makes something interesting, and to focus on that point. I think those lessons are of value to a photographer.

“I also had a brief stint in medical school, for just over a year, and I think that also taught me a couple of valuable lessons. First, I learned the relationships that go on inside the body, the nervous system and the muscles and so forth, and how they're held together by the skeletal system, which is valuable in a funny sort of way. Also, I think medical school was where I first became interested in the mechanics of a camera — the lens being like the human eye, the retina actually being like the multicolored coatings on film. So once again it's a funny sort of relationship, but I don't regret the 18 months I spent on that side of my education.

“I probably got into the journalism business because of my father. He was the Paris correspondent for a number of London newspapers while I was growing up, and it seemed to me that he lived a very exciting life. He knew all the French politicians, from the prime minister on down, and he was constantly in the center of things because of the people he interviewed — Mussolini, Hitler, Gandhi. My father was actually responsible for working out a sort of peace pact between Gandhi and the British government, acting as an emissary. They released Gandhi from jail with the understanding that the strikes would stop in India.

“Anyway, I was obviously interested in journalism, but at the same time, I was very keen on films. I made some amateur films at school, and I tried, but was somehow unable, to get into the film business. I was probably 22. So then I went to Fleet Street, the English press center, and worked there for three years. I always had a Leica camera around my neck, and on the way to and from the office, I was inclined to take a few pictures, and occasionally some of them were published. So bit by bit, I went into stills.

“I gradually began to make a living as a photojournalist. One day, I was interested to read about the city of Danzig. At that time, 1939, it was considered to be a danger point, a catalyst for war breaking out between England, France and Germany. I was conscious of the fact that although I had been a journalist for three years, and presumably knew something about world affairs, I hardly knew where Danzig was. And I thought if I didn't know, the chances were that the average man on the street didn't know either. I thought it was crazy, here we are on the brink of war, a lot of people losing their lives for something that was starting in a place that they didn't even know anything about. So I decided to try and go out there. I asked Life magazine to give me a float, and I went off to Danzig with my Leica.

“I found myself in the middle of an absolute, silent Nazi invasion of a peaceful sort of Polish town. There were the brown shirts and the black shirts, all stalking around, the Hitler movement, and all sorts of shops being defiled, with ‘Jew’ written on the windows, shop windows smashed, and things of that sort. There were beatings going on. I took a lot of pictures of all these things and came back to London. “In London, I was approached by Herbert Kline, an American director who specialized in documentaries. He asked me all about what I had done in Danzig, and told me he was doing a picture called Lights Out in Europe, a documentary about Europe's preparations for war. A very charming thing he told me about the film — that the script was being written by Roosevelt, Chamberlain, Hitler and Mussolini, and it was being written day by day. They had English material for the film but needed German material, so he asked me if I would like to return to Danzig with a movie camera. Of course, my heart skipped a beat with excitement, and I said I would go."

For the sake of safety, Slocombe had to be out of Danzig prior to the publication of his still photographs - before the Germans found out about them. This gave him about three weeks. He was given a handheld Eyemo and a short course on loading, and returned to Danzig alone. He filmed many of the scenes he had previously photographed with the still camera, and captured some new scenes.

“Things were obviously getting worse. There was a big synagogue set on fire, and I was filming it, and I suddenly found myself being shaken, which annoyed me intensely, because it really didn't help the stability on which I normally pride myself. I was being arrested. They frogmarched me to a nearby Gestapo building. The day before, I had been filming the forbidden doors of the place, little realizing that I would finish up by being thrown in there myself. I spent an uncomfortable night there, and I wasn't allowed to get in touch with the British consul. I finally talked my way out.

"My films were taken back to England in a diplomatic bag, and the British contingent there escorted me to the Polish frontier. I went to Warsaw, where I met up with Herbert Kline. Much to my surprise, Herbert had brought my English wife and our two young daughters along. It was toward the end of August 1939. One knew that something was going to happen very shortly, things couldn't stay the way they were for very long. And I thought that this was a fine time to be in Poland with your family," Slocombe chuckles.

"We made a lot of arrangements with the Polish army to film stuff, but then on September the first, we were awakened very early in the morning by the first planes and bombs. And that was the beginning of it all.

"We had all sorts of adventures trying to get out. We tried to follow the Polish government. We knew that they would probably go to Romania. We got on a train, with great difficulty, but it turned out to be the wrong train. Both our train and the Polsih government train ended up getting bombed, anyway. So after another series of adventures, we decided that instead of going south to Romania, we would go north. We bought a cart and horse, and trekked for days, just making it into the Baltic countries hours before the Russians came through and cut off their frontier."

Slocombe's adventures continued. He shot film at the Maginot Line during the "phony war" period, and managed to be in Amsterdam when the second major German offensive swept through. He spent most of the rest of the war years on Atlantic convoys, working for the Ministry of Information, and shooting propaganda films.

At the time, Ealing Studios had an agreement with the Ministry of Information that allowed the studio to use any approved footage for their purposes. This provided Slocombe with his opportunity, and after the war, he stayed on with Ealing for 17 years, shooting over 30 pictures there.

"When I came to Ealing, everything that I knew about camera work I had pretty much figured out for myself," Slocombe recalls. "That's the way it continued for most of my career. I never really had any formal training. Everything that I had filmed up until that time had been on a sort of documentary basis - I photographed what existed. Of course, in the studio, you don't photograph what exists, you have to invent and create something that doesn't exist. It only exists once you've lit it on the floor.

“I had never seen anybody light a night shot before, so I had to work it out myself - find my own modus vivendi. As I said, this self-training has always been allied with my awful memory, forcing me to learn everything as I go. This way of working did get me in trouble, though, on a number of occasions. When I joined the union, I realized that I had never been on a studio stage before. It was Cavil Canti's idea that I operate on a picture for Wilkie Cooper (The Big Blockade). I had never operated on a picture and I haven't since. I think Wilkie must have been appalled to have me as an operator, rather than somebody who really knew how to do it.

“Here I was trying to figure out a Mitchell camera with a moving finder. I never fully understood what one had to set - you have to set for each lens, and reset every day. But I was inclined to just take the camera as it was, and be quite happy looking through the finder. I was slightly worried the next day when the compositions weren't quite what I remembered seeing. I think that the final straw for Wilkie came on the day we were watching rushes, and on the side of a picture that otherwise looked magnificent and was very nicely lit by him, you saw Wilkie himself walking along with a handheld lamp which he was using for filler light. He wasn't in my finder, but he was in the camera, very nicely framed along the side," laughs Slocombe.

Unfortunately, Slocombe's alleged lack of memory extends even to the picture he just shot. Although he assures us that Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade is a wonderful film, with lots of inventive gags, thrills and chills, he can't recall any of them specifically. “Everyone has to find that out for themselves," he says demurely. “Of course, they're very secretive about the whole thing. But I told them they wouldn't have to worry about me giving anything away — I don't remember! Very often, I'll finish working on a movie, or even go see a movie, and my wife will ask me what it was about, and I'll have to say that I really can't remember. I can say what it looks like photographically. But by the time I get to the end, I can't remember how it begins. If it's a murder story, at the beginning, someone gets murdered, then I can never quite follow the plot as to all the complications. Everyone looks terribly worried all the time. But then at the end, suddenly they all look happy again, so I go out and tell everyone it's a wonderful picture, you must go see it," he laughs.

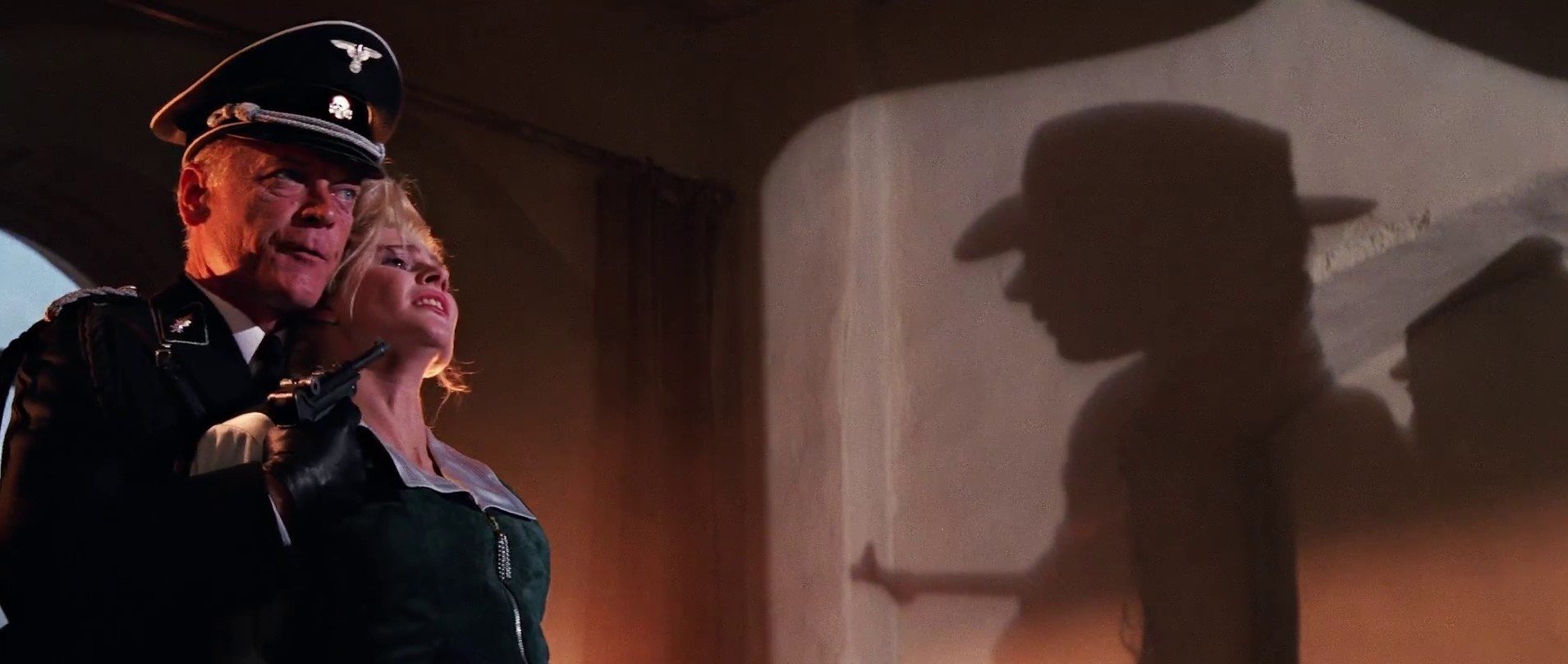

So we'll take it from Slocombe, a man of adventure himself, that it's a good movie. Although he would deny any similarity between himself and Indiana Jones, Slocombe does admit, “when I see those Nazi uniforms from wardrobe, I always hark back to the real ones I saw in Danzig."

You’ll find our complete coverage on Raiders of the Lost Ark here, and Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom here.

Slocombe was honored with the ASC International Award for his exemplary career in 2002.

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.