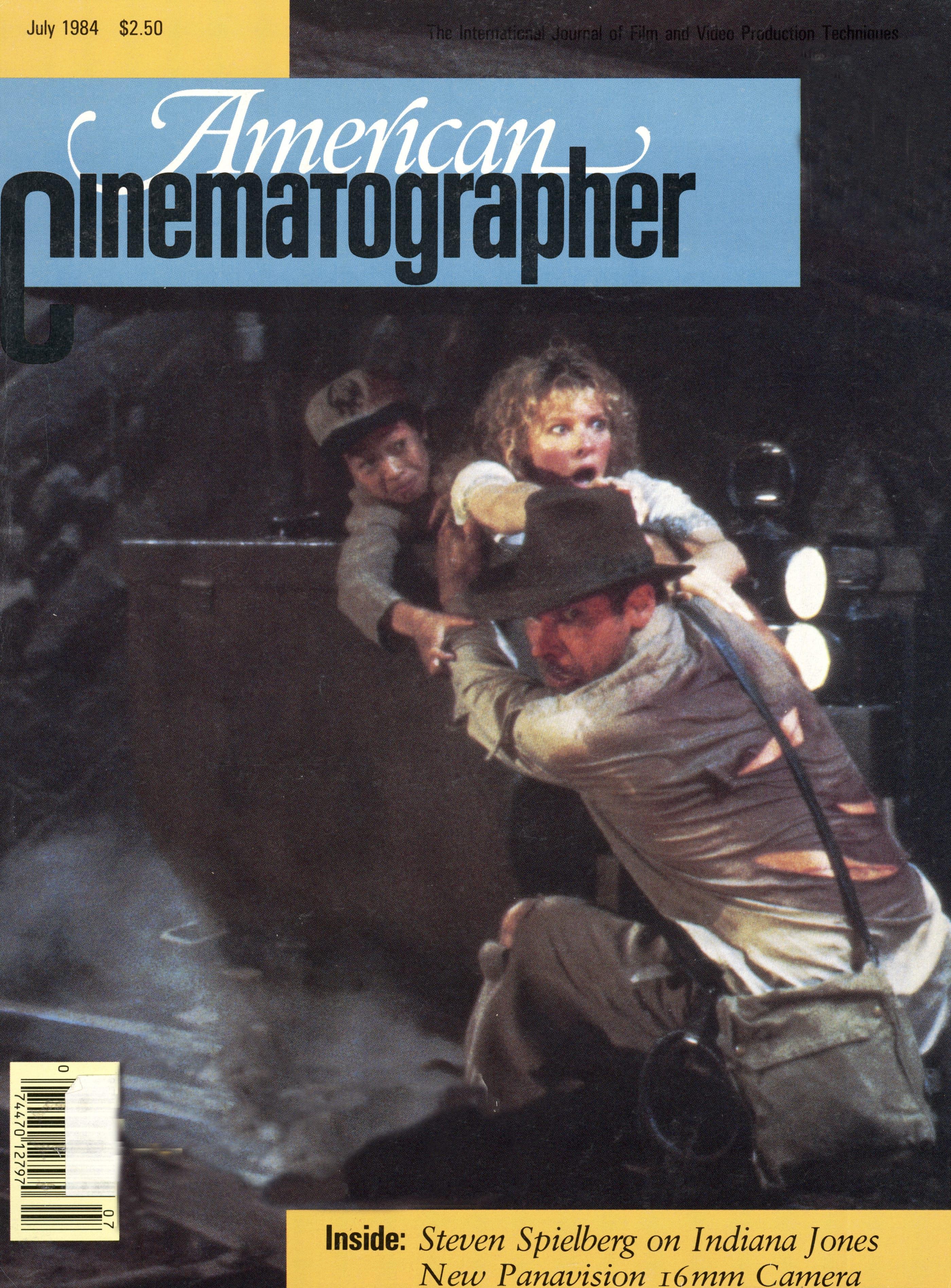

Steven Spielberg on Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom

“Every director, in order to be responsible to the people who have hired him to make a good movie, has to be a good producer, as good a producer as he is a director.”

Edited by Merry Elkins

Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom is a fast-paced, finger-lickin’ good feast of chases and roller coaster rides, bad guys and good, cliffhangers and wild stunts, special effects and extravagant lighting. Watching it is a class in filmmaking, a study in how to piece together every conceivable element of imagination into one widescreen dream.

It’s a “popcorn adventure with a lot of butter. A movie about a kind of life that is totally unattainable, where you wake up at one o’clock in the morning after seeing it and say, ‘That’s impossible. I don’t buy it.’ But you bought it when you were watching it, and that’s all that’s important.”

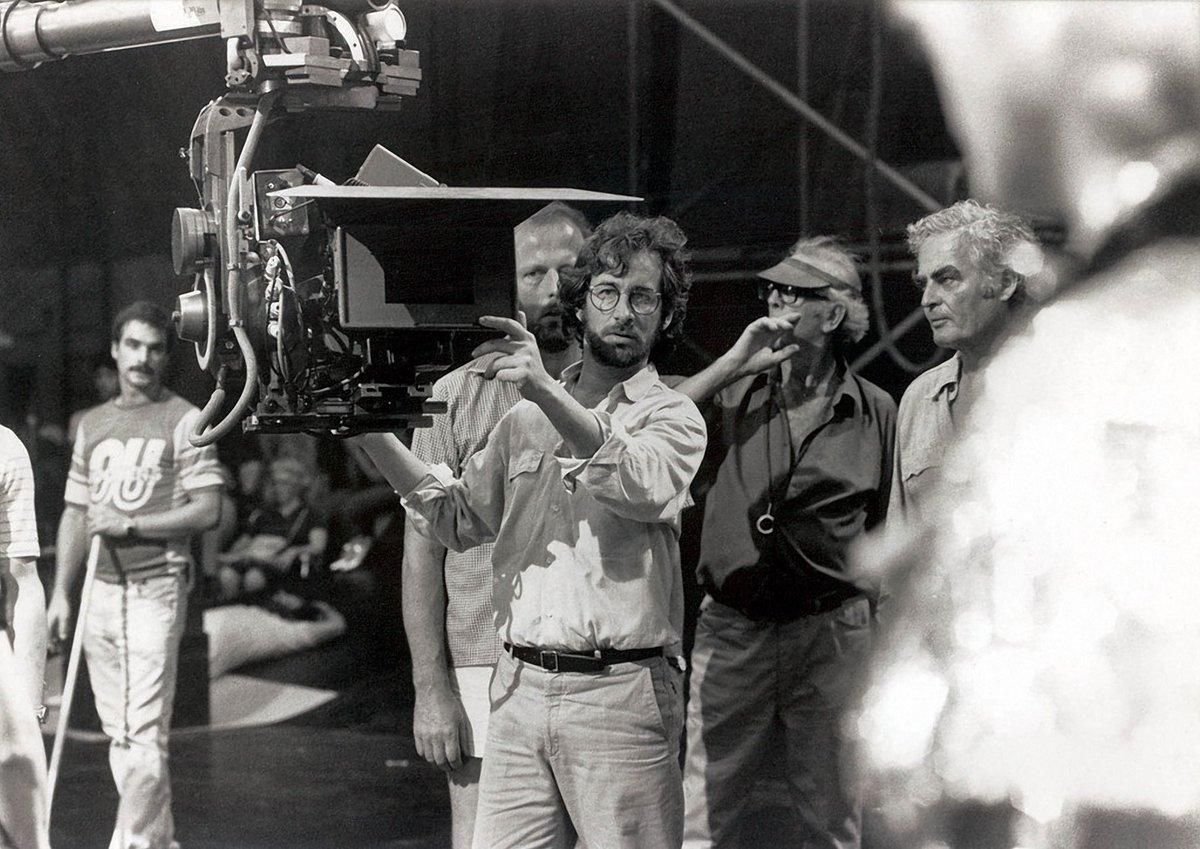

Not the words of a critic, but of Indiana's director Steven Spielberg, who discussed the making of the film in an exclusive interview with American Cinematographer. The following remarks are taken from that interview, tracing the development of the visual style for the film from storyboard to cutting room.

“A lot of directors like to store things away in their heads, becoming the secret force of their own battle plans. They leave the crew high and dry, wondering what they’re up to, and then they don’t get that involved. I’ve always felt that the people who make direct contributions to what goes on the screen need to have, at least in my movies, a firm idea of what we’re collaborating towards, and storyboarding is a way to communicate, before one frame of footage is exposed, what the director is thinking about. It’s a way to draw the play on the chalkboard before the ball is snapped.

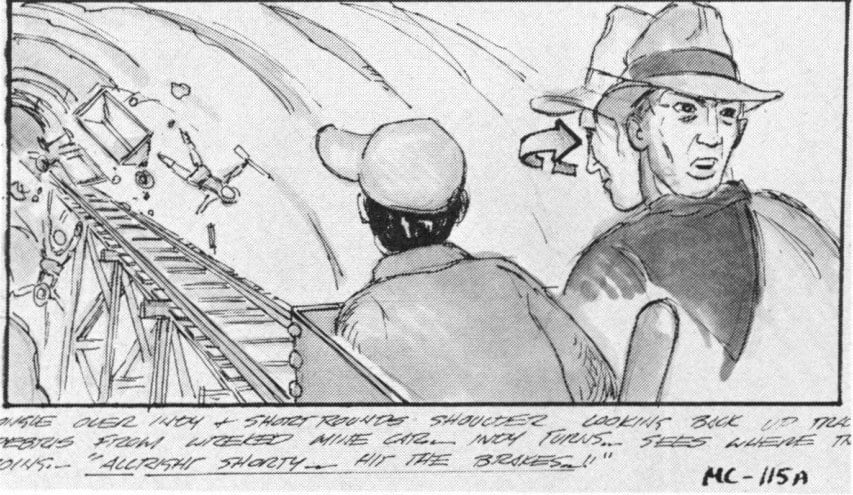

“Rather than bringing a script with me when I shoot a particular sequence, I work from storyboards. For Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, I developed about 4,000 individual frames which were drawn by Ed Verreaux, Joe Johnston, and even Elliot Scott, our production designer out of England, who did some thumbnails and creative paintings himself.

“I start with generic illustrations of principal master shots, which gives me a geographical floor plan of how to pace the sequences and break them down into cuts.”

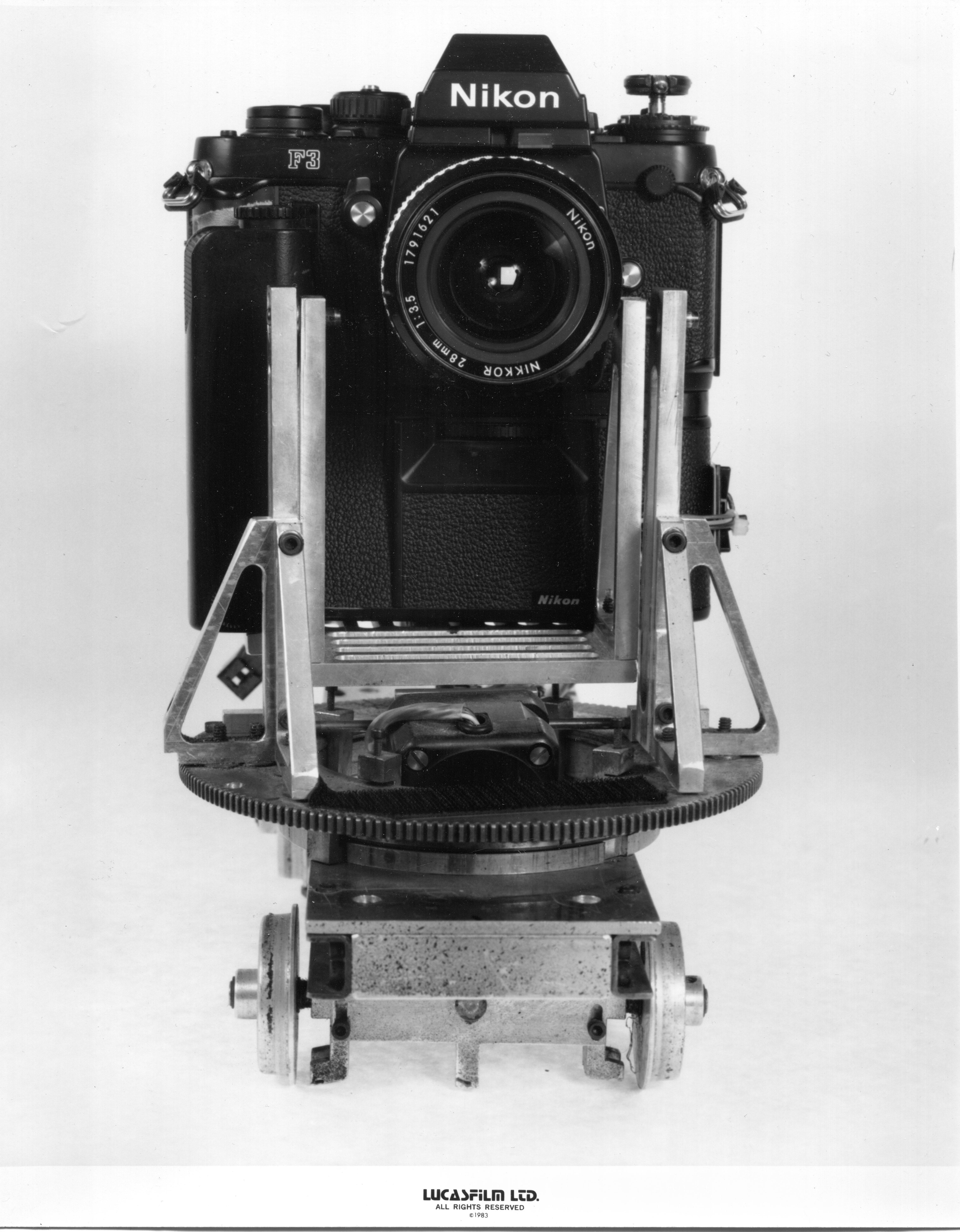

“I start with generic illustrations of principal master shots, which gives me a geographical floor plan of how to pace the sequences and break them down into cuts. I use that master shot to pick my angles. I had about 10 master shots for Indiana Jones, and then Elliot Scott caught up with me by building these elaborate miniatures of all the sets. So rather than having to work from a flat piece of paper one-dimensionally, I could take my Nikon with a 50mm macro lens and get right down into a 17" cardboard set with 1/2" cardboard characters and photograph angles. I planned every shot that took place in the crusher room that way, in the quarry cavern, the shots in Indiana’s and Willie’s suite during the love tease, and a lot of the mine train chase that way. It was all there as sort of a banquet, a visual feast.

“When I’m sketching an angle, I draw seven or eight frames that tell a small story. I do the thumbnails myself, which are often absolutely impossible to interpret, and I need to stand over the artist to explain which side is up. These shots are all subject to change, and I usually don’t shoot every one. I always overdraw. I draw more than I can possibly shoot in one two-hour movie. Then I begin cutting the storyboards down, taking seven or eight different frames, and finding one shot that symbolizes everything I want to say in those drawings. That gives it economy and substance and a lot more energy. I cram every bit of visual information into one frame. The audience today, especially with the influence of television and the 30-second, often 10-second commercial, is seeing faster than they saw in the 1950s and '60s. With every generation born, kids are taking information in quicker than we did when we were kids. I don’t have to hit the audience over the head with seven shots when two might tell the story, the two that really have all the information in them; then I’ll find areas to bridge with little cut-aways I might want to do to protect myself if the scene’s too long in the editing room later.

“Indiana Jones is not a ‘personal film.’ It’s an audience entertainment. It’s fun for everybody. And all the actors learned to act in a different way. They learned to paint their emotions by the number.”

“There are a lot of things you can wing if you’re making a film like Terms of Endearment, because it’s very hard to get actors in a highly charged emotional sequence to follow your pre-concepts and oblige every one of your paint-by-the-number directions. I wouldn’t ask an actor to do that if I made a relationship movie. E.T. was a relationship movie, and I didn’t storyboard it except for the 40-odd special effects shots which I had to storyboard for budgetary reasons. I didn’t want to impose a kind of visual rhetoric on the kids because I knew they’d lose their spontaneity if I forced them to follow cartoon drawings. I wouldn’t do that in a love story. But Indiana Jones is not a ‘personal film.’ It’s an audience entertainment. It’s fun for everybody. And all the actors learned to act in a different way. They learned to paint their emotions by the number. Kate Capshaw, Harrison Ford, and even the young boy, Ke Huy Quan, who had never acted before, fell into step with the storyboards. They were able to give credible performances when the light was hitting them at a certain time or when they hit the mark which put them into exact alignment with the blue screen. Indiana Jones is a very technical movie, and the actors had to be technical without losing their own believability as characters in order to pull it off.

“Storyboarding also performs another service which I find fundamental. It exhausts me. It makes me tired and a little bored with the sequence. In a way, I’ve already shot that sequence by sketching it; then, by reviewing the sketches I’m able to look at the sequence and say, this has no imagination. This is not interesting. It forces me to rethink each scene. Often I’ll sketch something in a safe manner, in a way that if worst came to worst, if it stormed and we lost a day I’d have something to fall back on.

“I did this for four months on Indiana Jones. I mapped out everything. I knew exactly what the different pitfalls and cliffhangers were going to be, and how they were going to be lit. Those four months also involved scouting locations and watching the sets go up. Standing in a basic plywood structure that hasn’t yet been plastered can be inspirational. It showed me how high the sets were and how much breadth and depth they had. There were times I re-drew whole sequences because of the sets.

“I love location shooting, but the older I get, the more I’m getting the homing instinct to build it and shoot it indoors.”

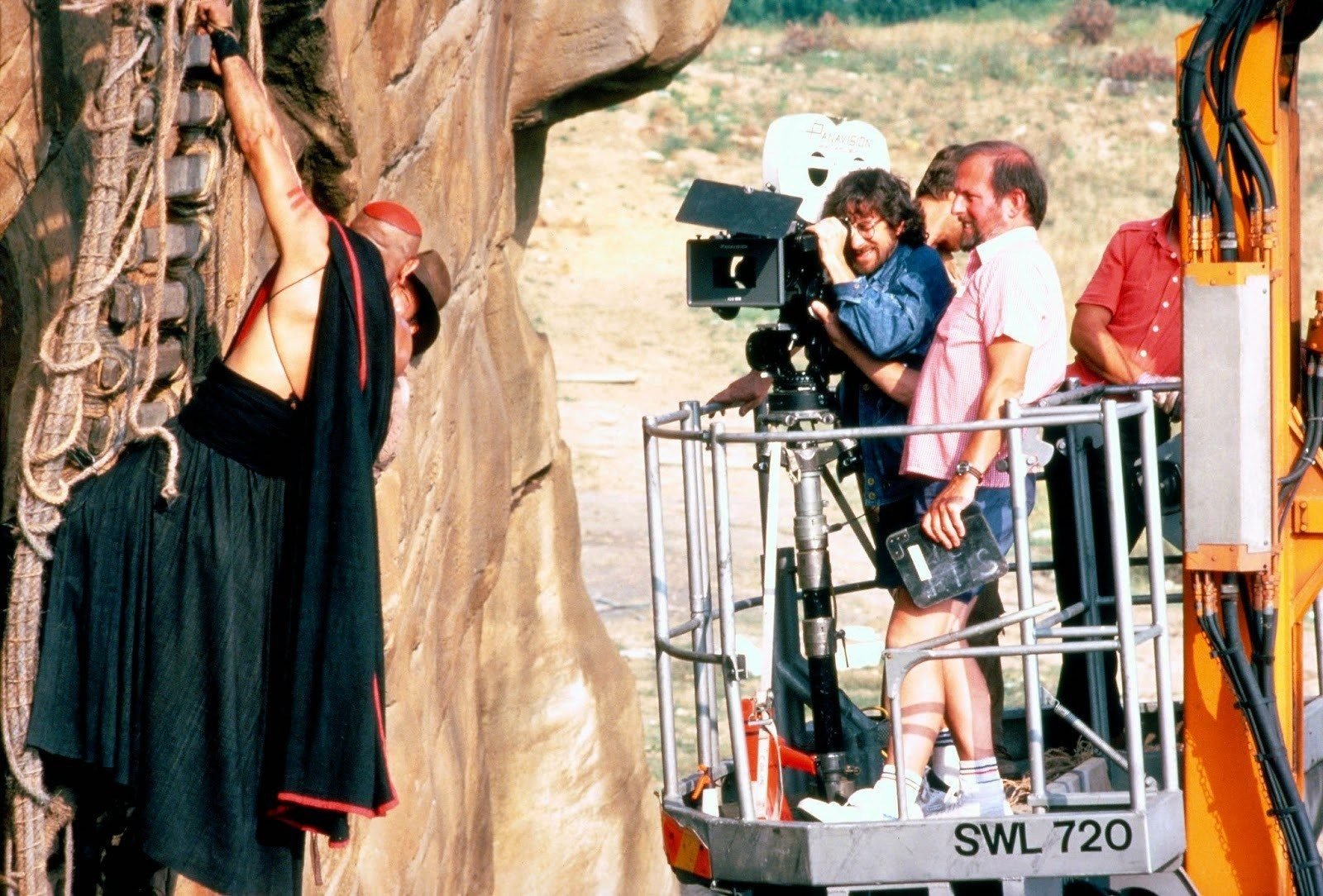

“We shot for 85 days in Macau, Sri Lanka, London, and in San Francisco. We shot all the bluescreens at ILM. The jungles and elephants were in Sri Lanka, but all the exteriors of the palace were paintings and miniatures.

“The movie was shot principally 80 percent on sound stages in London and 20 percent outdoors. For me, this was a pleasure. I love location shooting, but the older I get, the more I’m getting the homing instinct to build it and shoot it indoors. I don’t like to wait. When it rains on me, and I want sun, or when it’s sunny and I want it to be overcast; I feel better when I can create the environment.

“We had a budget of $28 million, and we delivered Paramount a $28 million movie. I went over budget in some sequences, and came in under budget in others. I went over schedule with certain scenes, and came way under in others. It was almost all a wash. We actually came in five days under schedule.

“There are those scenes where I want to selfishly say, ‘Look what I did,’ and Dougie has his moments where he can say that, too.”

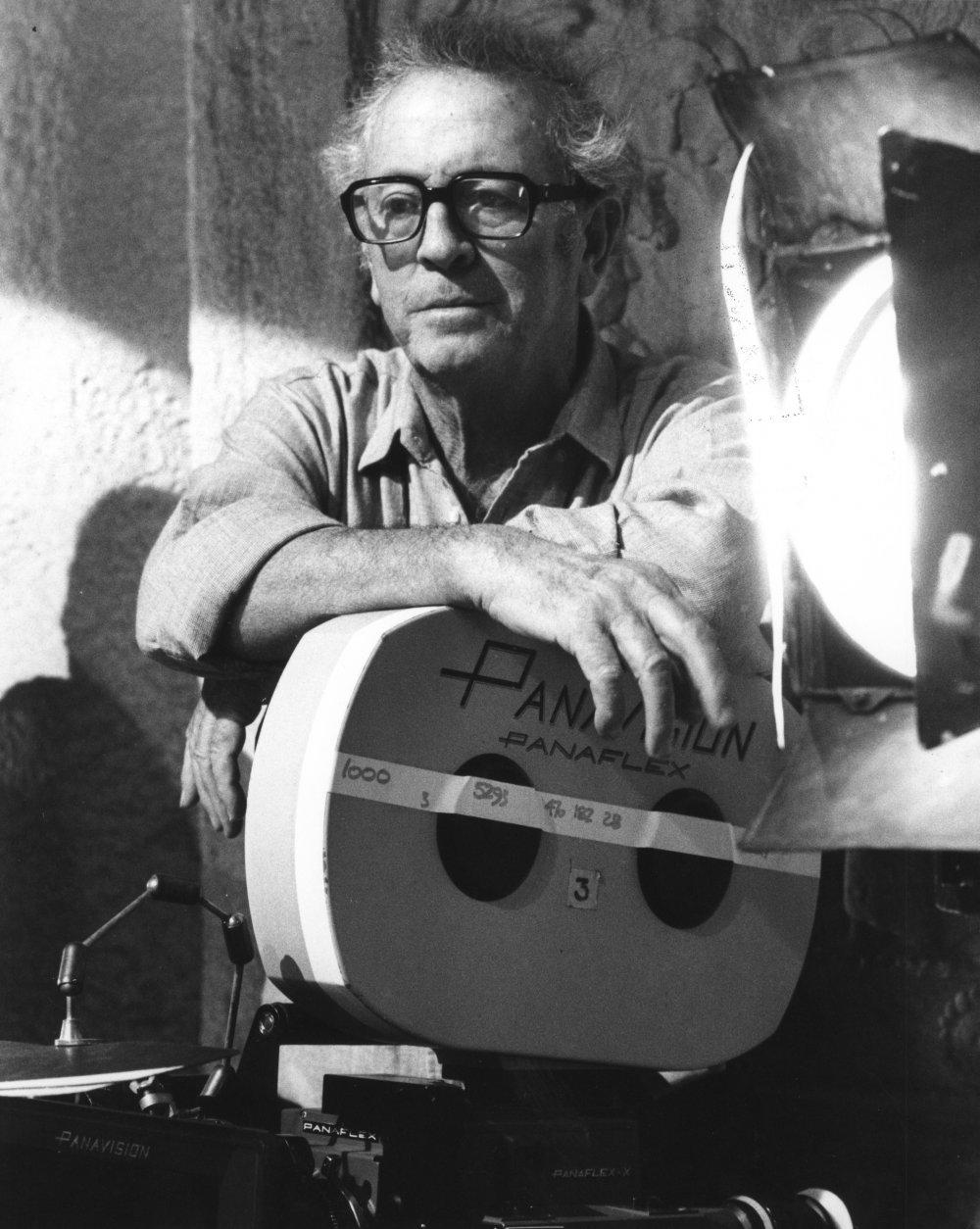

“Sometimes I consciously cut days out of the schedule knowing I needed five more elsewhere. It was like robbing Peter to pay Paul. I needed extra days in the quarry room, so I took days out of the banquet scene. I needed more days on the mine train set, so I took a day out of the spike chamber. It’s really a matter of how much time you give the crew to finish a shot. When I needed to cut a day out of a sequence, I went to Dougie [Slocombe, the director of photography] and said I needed him to help me buy a day or two that I had to have two weeks later when we would get to the quarry set. Could we go a little faster? And Dougie would go faster, the whole crew would get on our side, and I’d get 30 shots in that single day as opposed to 19 the day before. It’s just a way of cooperating to buy time later. Of course you can’t make deals with the crew to work faster all the time. I only needed to rob Peter to Paul perhaps four or five times. Maybe the lighting could have been better for Dougie’s taste, but we both agree the audience doesn’t notice. The overall impression is a beautifully photographed movie. I’m that way directorially. There are certain sequences where I’m really proud of the shots, and others that just state the events of the story. There are those scenes where I want to selfishly say, ‘Look what I did,’ and Dougie has his moments where he can say that, too.

“Movies are unharnessed dreams, but if they become too costly, or if danger is a factor, or it will take 10 years to get there, you have to pull back on the tack and compromise your dream. The mine train chase, for example, seemed impossible before we started shooting it, but with the help of Dennis Muren [ASC] and all the creative geniuses at Industrial Light and Magic, we made the impossible, possible. In other instances there were things I visualized but couldn’t do because of time and money. I wanted the quarry fight to be even more complicated than what’s on the screen right now. One of the reasons I enjoy making Indiana Jones movies is because I’m a firm believer that in an adventure saga every sequence needs to have two or more activities happening simultaneously. Where Indiana is accusing the Maharajah and the palace authorities of stealing the Shankara stone from the ancient village, on the other side of the table in this palace restaurant, unspeakable entrees are being served to Willie Scott and Short Round. With the sequence inside the crusher room as Indiana and Short Round are about to be crushed or skewered, whichever comes first, Willie is having her own problem with tens of thousands of insects. But when we finally arrive at the quarry scene where Indiana fights the giant temple guard on the moving belt heading to the stone crusher, I was interested in creating a third and fourth series of occurrences. No major sequences were eliminated due to production considerations because we had underwritten the action as opposed to overwriting it. I felt everything was lean. All the action sequences in the script were in short form. We talked about the most amazing mine train chase, the most amazing crusher room scene, and the most amazing cliffhanger over a 1,000' gorge. But it all didn’t make it on paper, and I found it was a lot easier in my storyboard to extend these sequences even beyond what we had written.

“The rock-crusher room scene with the fight on the conveyor belt was particularly hard to pull off because by the time we got to the end of the take, we’d be too close to the crusher. I’d look down at the crusher and say, ‘Hey, we aren’t supposed to be anywhere near the crusher for another two pages. Get back.’ The continuity was a very hard. The sequence starts 70 yards away and by the end of the sequence, they are actually at the crusher going into it.

But I had to cheat all over the place. I cheated it by 20' a shot. Sometimes were 20' closer to it, and four cuts later, 20' further away from it. But what makes this film and movies like this believable, is that we never defy gravity. No one goes off a cliff, stands in midair, looks down and waves bye-bye. Yet we come very close to that, and its my job to walk the thin line between the incredulous and the impossible. To keep it entertaining without tipping one way or the other. And to keep it so fast, the audience doesn’t have time to question what works and what doesn’t.

“My job and my challenge was to balance the dark side of this Indiana Jones saga with as much comedy as I could afford.”

“When George Lucas came to me with the story, it was about black magic, voodoo and a temple of doom. My job and my challenge was to balance the dark side of this Indiana Jones saga with as much comedy as I could afford.

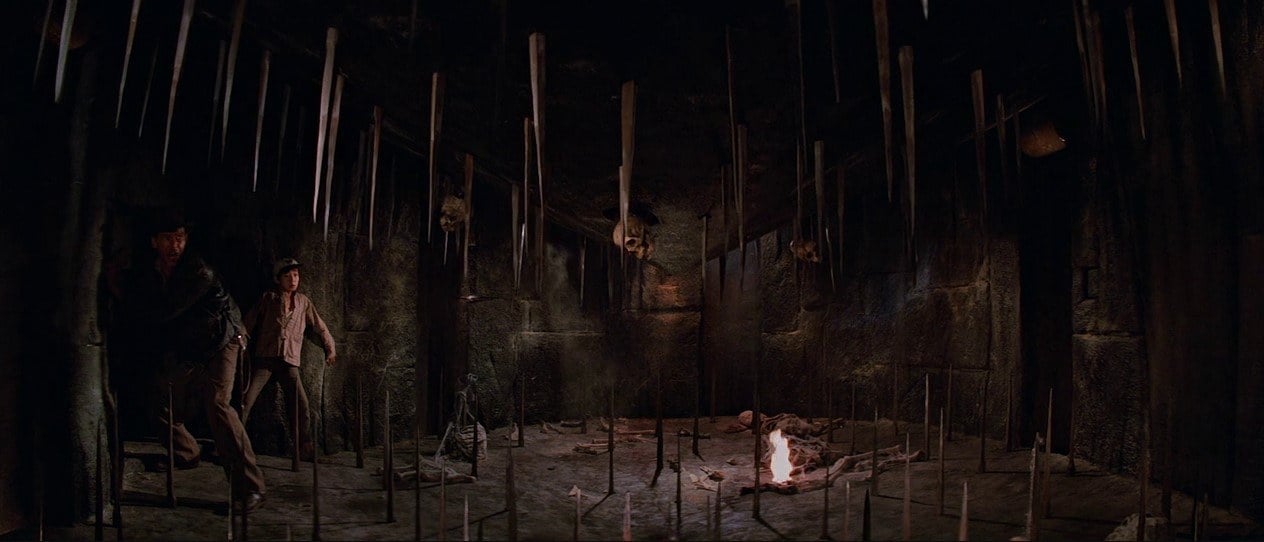

“In many ways, the visual style of the film was conceived when George told me the story, which was a very rough sketch of the movie he wanted us to help him construct. I heard a couple of things. I heard Kali Cult and Thuggees. I heard temple of doom, black magic, voodoo, and human sacrifice. When he said words like temple of doom and black magic, what came to mind immediately was torchlight and long shadows and red lava light. I felt that dictated the visual style of the movie. Once you’re underground, there’s no sunlight seeping through. I wanted to paint a dark picture of an inner sanctum. I didn’t rely on magazine pictures as I used to, looking at National Geographic pages or in a photography magazine to show the cameraman what I liked. I relied more on what it would look like if an entire set had only low wattage light bulbs recessed in nooks and crannies. It suggested the Bela Lugosi light you put under the vampire’s face that casts a nose shadow across the forehead. It suggested a lot of spooky, creepy, crawly, nocturnal imagery.

“All the lighting effects were floor effects as opposed to putting in a graduated filter or putting on a coral filter, or even hooking a piece of cyan gel to the lens. Dougie Slocombe likes to mix light and so do I. We agreed on that for Raiders of the Lost Ark, even though Raiders had a different visual approach and a different philosophy. Raiders was outdoor adventure and the sun was our ally. In Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, the arc, 10K and the baby were our allies. Often just the light of an actual torch was plenty with the assistance of the new fast [Eastman Kodak 52]94 stock.

“The color scheme evolved out of many production meetings with our costume designer, Anthony Powell, myself, Elliot Scott, and Dougie Slocombe in deciding what the film was going to look like. I wanted it to be filled with bright colors like a classic Technicolor movie. I especially wanted the banquet sequence at the beginning of the picture to be like The Adventures of Don Juan. Palatial, flashy, and motley in the choice of primary colors for the costumes and walls. Decadent. We wanted it to be bright and gaudy. To mislead the audience and make them think, with the dancing girls and exotic characters and their colorful costumes, that Indiana Jones’ adventure was going to take place on the surface of the world. But the minute he goes into his room at night and discovers the secret passage which leads into the inner sanctum the set and eventually to the Temple of Doom, I wanted the shift in style to very dark and low key.

“For the banquet scene, I just turned to [Slocombe] and said, ‘Make it like an old 1930s musical where it looks like there are 100 arcs up there — where it looks bright and decadent and sexy.’”

“In Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, and in any kind of fantasy adventure saga, you take the audience away from street realism, and deliver them into an entirely different universe. You can’t take it literally. I want people to take the experience of going to see the movie seriously, but it’s important in a picture like this to create a world they’ve never before experienced. And that world cannot be compared with the world they return to two hours later. That’s why I feel I had the freedom to take more license with a picture like Indiana Jones than I took in ET. When you have an arch villain as broad as Mola Ram, the evil high priest of the Temple of Doom, I certainly didn’t want to shoot him in a naturalistic setting. I suggested to Elliot Scott that the stone they tie Harrison Ford to look like a demented, deformed skeleton with candles burning in the eyes, with candles on top of the head with wax-like hair melting down the sides of this scary obelisk. Across the hall, I wanted the entryway into what we called the whipping chamber, to look like a demon with a mouth wide open. And in the sequence where Mola Ram forces Indiana to drink the blood that puts him into the black sleep, we went broad with the lighting, using hard lights, and lighting it from the floor as if it were coming from fissures illuminated by molten rivers of lava. We used only a few top lights to highlight and separate the characters from the background.

“When you have an arch villain as broad as Mola Ram, the evil high priest of the Temple of Doom, I certainly didn’t want to shoot him in a naturalistic setting.”

“When the actors did something special, I would go in and allow Dougie the opportunity to light it better for a close-up. On a master, Dougie couldn’t get the nuance lighting in. With a second camera and 100mm lens grabbing the closeup, the lighting wasn’t as good because our concern was with letting the audience see the set and the outline of the characters in the dark. Dougie would always encourage me to pick out something I found to be a favorite moment and cover it so he could do it justice with his lighting.

“The reason I like working with Dougie is that he’s a glamour photographer. He can shoot any woman and put her on the cover of any magazine in the world. Yet when it comes to rolling up his sleeves and getting dirty and down into the nitty gritty of ancient tombs, he can create impressions of foreboding and mystery. I witnessed his skill one day when he was shooting little children, filthy and dirty, digging for the lost Shankara stone in this huge quarry cavern with very bizarre lighting. There were lights hidden under rocks shining up at their faces, lights out of little holes in the walls just giving them enough face light to accentuate their pathos. The very next day he shot the love tease and lit Kate Capshaw as James Wong Howe [ASC] might have lit Greta Garbo. That, to me, is skill. Skill and real creative talent means doing many things well, not just one. And Dougie has variety. He’s like the Laurence Olivier of cameramen because he’s able to put a different mask on when the scene requires a different style of lighting. He doesn’t impose his own style on every movie he makes. He’s a chameleon. He keeps changing, not just from film to film, but from sequence to sequence. He’ll go from the slick Hollywood glamour of the overlit, splashy banquet scene to the one-stop push photography in the Temple of Doom.

“For the banquet scene, I just turned to him and said, ‘Make it like an old 1930s musical where it looks like there are 100 arcs up there — where it looks bright and decadent and sexy.’ A few adjectives and he knows exactly what to do.

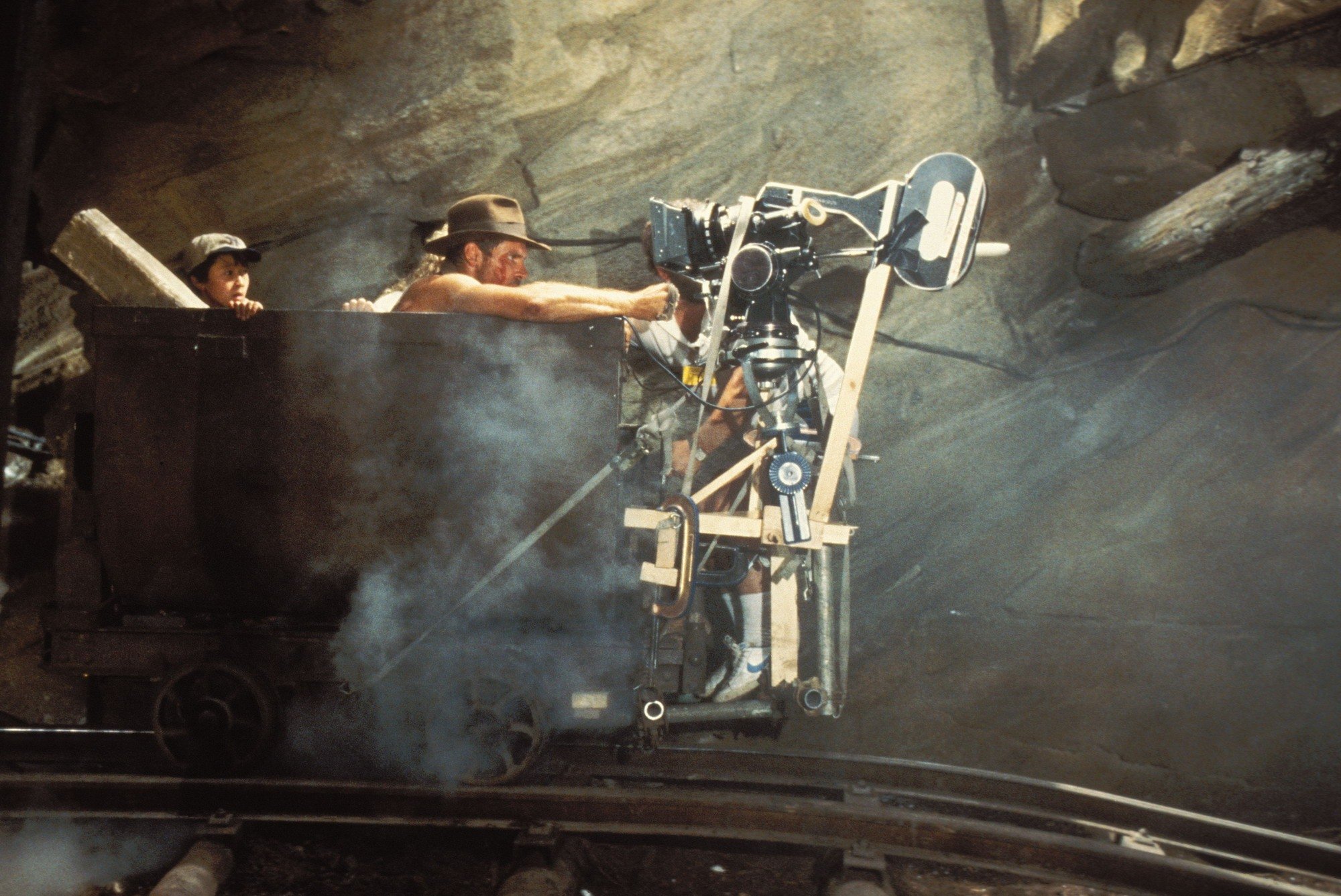

“What we actually did was build a roller coaster ride on the sound stage. And it really worked. It was safe. It was electrically driven. You could take rides, in it.”

“For the mine car chase, Elliot Scott and I designed the mine train full scale on one large sound stage in London and Dennis Muren, our special effects supervisor, matched what we built for the miniature shots. I didn’t quite know what I wanted this mine train chase to be. I had some elaborate storyboards, impossible to put on screen, and Elliot Scott told me he didn’t think he could do it justice with one circular track. So he built some variety into that track by constructing it on three levels. It goes 15' over the camera, then dips down to about 2' off the ground, then down one foot, down 2' more, back up to ground level, and finally back up eight feet. What we actually did was build a roller coaster ride on the sound stage. And it really worked. It was safe. It was electrically driven. You could take rides, in it.

“We built two loops, the mine train loop and a dolly track loop. I could sit on the camera with Chic Waterson operating it, and five people pushing the dolly from behind, we’d travel at the same speed as the mine train.

“One of the secrets to making that scene realistic was not locking the camera down. There are many mount shots that study Indiana and Willie in closeup. There are no process shots in the sequence at all. I used master shots with run-bys, or the camera was in the car, or running next to the car with the actors in the car.

“Before we shot, we did a steady test. What we discovered was that we could not get the camera steady. The photography on the first day of testing was almost unusable because the camera shook so much when it was in the mine car. Everyone said, ‘Gee, this looks terrible.’ And I said, ‘No, it doesn’t look terrible. It looks absolutely realistic. I took several rides in the mine car and this is what it looks like. It made my fillings fall out. This is what it feels like to be in a mine car without shock absorbers, racing downhill. I loved the fact that the camera never was steady. We even began to loosen the mounts as we shot so it would register more vibration.

“For the run-by shots, I found when I used a wide angle lens, it was too smooth. It was like a boat-to-boat shot on a calm lake. So, I only shot from the dolly to the mine car with 75s, 100s, and 180mm anamorphic lenses. This in itself made it hard for Chic [Waterson] because he was struggling to keep the actors in frame. But it gave a very realistic effect. Then Dougie and Paul Beesen, who both helped to shoot the sequence, put very hot lights every 20 or 30 yards so there would be sweeping shadows as the people went through different colored lights. We were careful to change the color of the gels so the actors never went through just white light. They went through reds, oranges, yellows, and greens. This gave the feeling of speed and variety of location.

“The marvelous thing was that just by changing the position of the lighting and the color gel over the light, you never felt you were in the same part of the circular set more than once.”

“Since we were going in only one direction, and never faster than ten miles per hour for safety reasons, what we did was shoot an entire loop of the track with yellow light. Then I’d ask Dougie to change all the gels in his lamps and go totally straw, and we’d do another pass in straw light. Then we’d come back and I’d ask Dougie to light half the set in straw and half with red as if they were going through fissures where lava rivers flowed beneath. Then on the same boring circle, we’d go around with the actors and they’d do the dialogue involving the red color. Every time I went around the track, Dougie kept varying the lighting. The marvelous thing was that just by changing the position of the lighting and the color gel over the light, you never felt you were in the same part of the circular set more than once. The set itself never changed, though we did build a section of parallel track for what we called the taffy pull with Short Round between the two cars and the live action footage was supplemented with miniature footage. The high overhead shot of Short Round between the two cars going over the lava pit, for example, is a miniature

“Even though the mine car wasn’t going fast, it looked fast because we shot parallel to and very close to rock walls.”

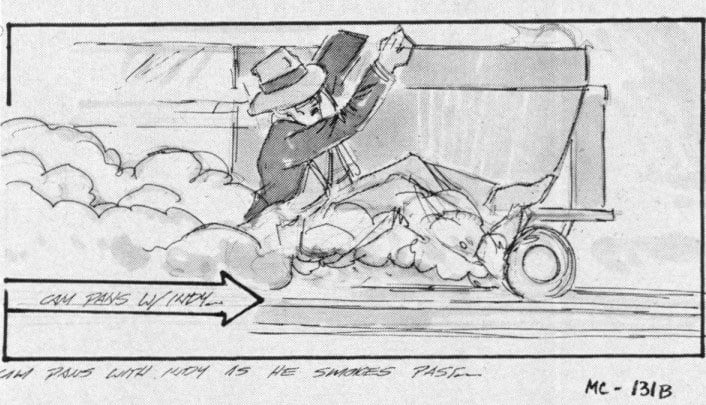

“One day, accidentally, the actors went through a large lump of smoke. The effects man didn’t take the B-smoke and properly paddle it evenly across the track. He created a cloud that hung in the air. When the mine car hit the cloud it created a con trail which flowed off the shoulders and hat of Harrison Ford, and I just loved it. It was an accident, but from then on, I had the effects man lump his clouds in mid air.

“Even though the mine car wasn’t going fast, it looked fast because we shot parallel to and very close to rock walls. When you drive in your car, you can be going five miles an hour out of your driveway, but if you’ve got a retaining wall, it looks like you’re going 45 miles an hour. That’s why we shot a lot of the sequence flat to a wall.

“It would take about 25 seconds to make a complete circle around the track but I undercranked the camera to about 12 to 18 frames a second for everything except the dialogue. This made it look faster than it really was, but it also meant that the actual amount of screen time it takes to go around the track is even less. So out of about 12-second bursts of film, I built up a sequence that lasts seven minutes in the finished film.”

For the miniature work, “Joe Johnston, the art director in California, and I storyboarded shots, like the leap over the missing section of track. Then Joe went back to San Francisco from Fondon, and shot an animatic, or what we call a videomatic. He videotaped a little cardboard mini-car in a little cardboard set. The tape was transferred to film and I cut the videomatics with [editor] Mike Kahn into the 35mm footage we’d shot with the principals two weeks before. The videomatics were black-and-white, and you might see a hand in the frame holding a stick. At the end of the stick, was this little cardboard mine car. The hand takes the car on a left hand turn, then brings it up to the lens. Sometimes, the car would fall off. When the car had to spill the occupants out, you’d see a hand just throwing the car over the miniature cardboard track, and these little 4" cardboard dummies would fall out. But because of the videomatics, I was able to see what worked, what didn’t and how much more shooting I had to do with the principals. I actually had to go back and shoot a few extra shots because Joe had thought of a few real neat things we hadn’t thought of before, and they were so interesting, that it was worth bringing the actors back for two or three more closeups. Within two weeks after shooting the sequence, I had a seven-minute rough cut. To save money, I then cut out the videomatics I didn’t think were essential since each effects shot was going to cost $20,000 to $30,000. I knew that once we began shooting this stuff, I had to be very certain that what I was committed to based on the videomatics, was going to be what I would accept come hell or high water after seeing the results a half year later when the effects were completed.

“Our shooting ratio on Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom was three or four to one, just like in Raiders of the Lost Ark. That’s the real key to our shooting schedule. It might take two hours to light a master shot, but if you can get it on take three, you can get several other shots before lunch. If we get it on take 20, all you’re going to do is that master before lunch, maybe even after lunch. The actors I’ve worked with are more comfortable and more spontaneous in getting it all out in take one, two, or three. I’ve been very lucky to have actors who like to do it fast and move on to something else.

“The first cut I saw was about 2 hours and 10 minutes. When I showed the film to George at an hour and 55 minutes we looked at each other, and the first thing out of our mouths was ‘too fast.’ We needed to decelerate the action. I actually did a few matte shots to slow it down. We reestablished the palace outside in a night shot before going back inside again for example. We made it a little bit slower, not by lengthening the overall time but putting breathing room back in so there’d be a two hour oxygen supply for the audience. The final running time is an hour and 55 minutes with a 6-minute end credit.

“Every director, in order to be responsible to the people who have hired him to make a good movie, has to be a good producer, as good a producer as he is a director.”

“The reason I make these pictures is that they give me a chance to be, not myself, but a lot of people sitting in the dark watching a movie. It’s a chance to put on two hats, the directing hat and the audience hat. I get the opportunity to jump back and forth from the director’s chair wondering, ‘Gee, if I were the audience how would I like this scene to turn out?’ And then I jump back onto the floor of the sound stage and say, now that I’m the director, I can give audiences what I think they would like to see in a movie like this.

Every director, in order to be responsible to the people who have hired him to make a good movie, has to be a good producer, as good a producer as he is a director.

If he doesn’t actually function as a producer at least he needs to rely on people who are good producers and whom he trusts. On Indiana Jones I had a great belief in Robert Watts, the producer, and I trusted him with everything from scheduling and set construction to set striking to location hunting. Watts was on top of everything.

“We tried to work so that once we finished with a set, we struck it. This is like burning a bridge behind you. It doesn’t give you any choice but to accept what was shot and move on. I think a good producer will turn to a director when he’s most preoccupied with what he’s shooting now and say, ‘Do you want to go back and shoot anything else in the Pleasure Pavilion?’ And being preoccupied with the current scene, the director might say, ‘No, no, I don’t want to think about that. Go ahead and strike it.’ They’ll go ahead and strike it, and perhaps the director returns the next day with a great idea for the Pleasure Pavilion, and the producer shrugs and says, ‘You told me to strike it. It’s gone. It’s sawdust and nails.’ I save a lot of money by finishing a set. I convince myself that there’s nothing more I want to shoot there, and I walk away from it.’’

You'll find our complete Temple of Doom story with visual effects supervisor Dennis Muren, ASC right here.

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.