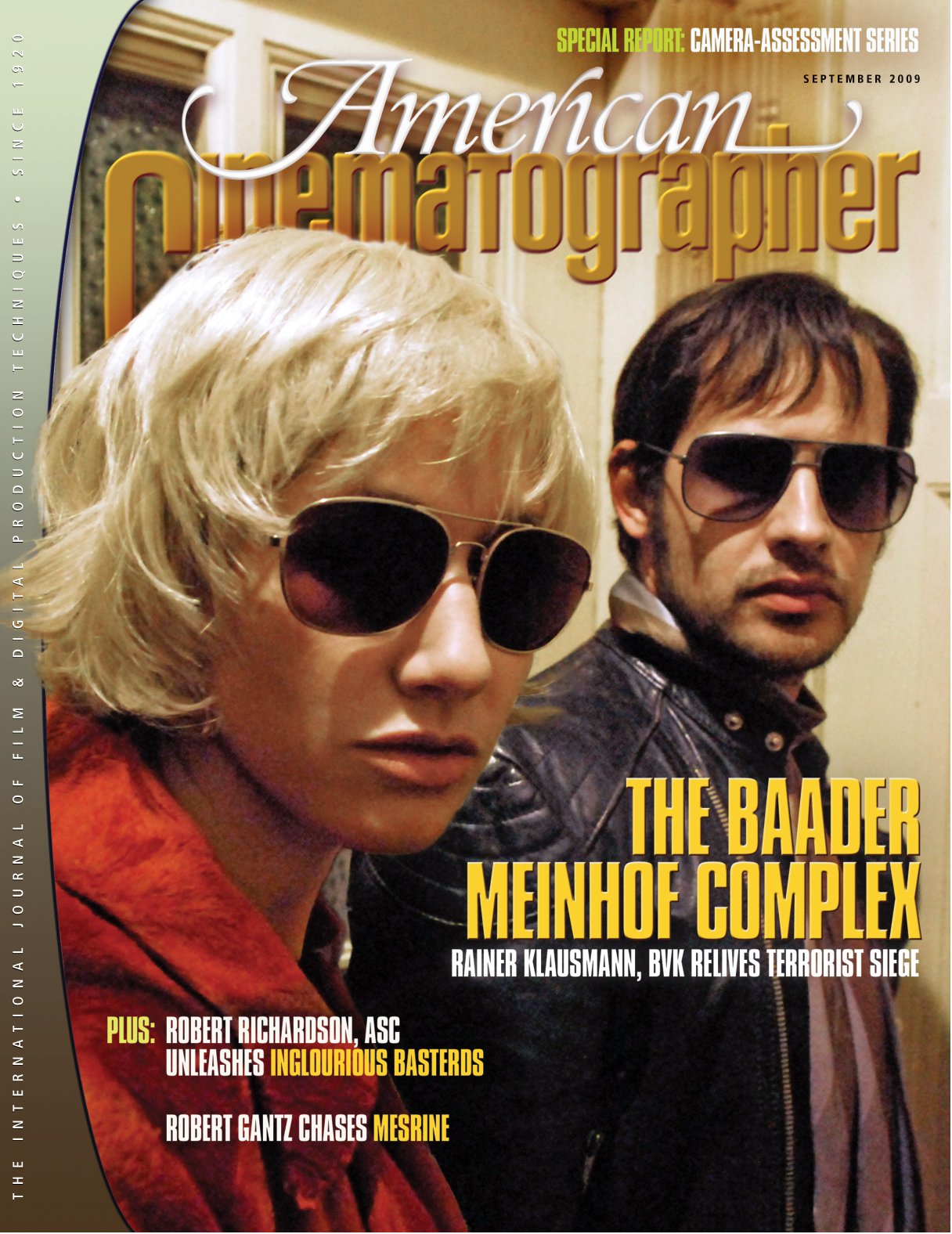

Inglourious Basterds: A Nazi’s Worst Nightmare

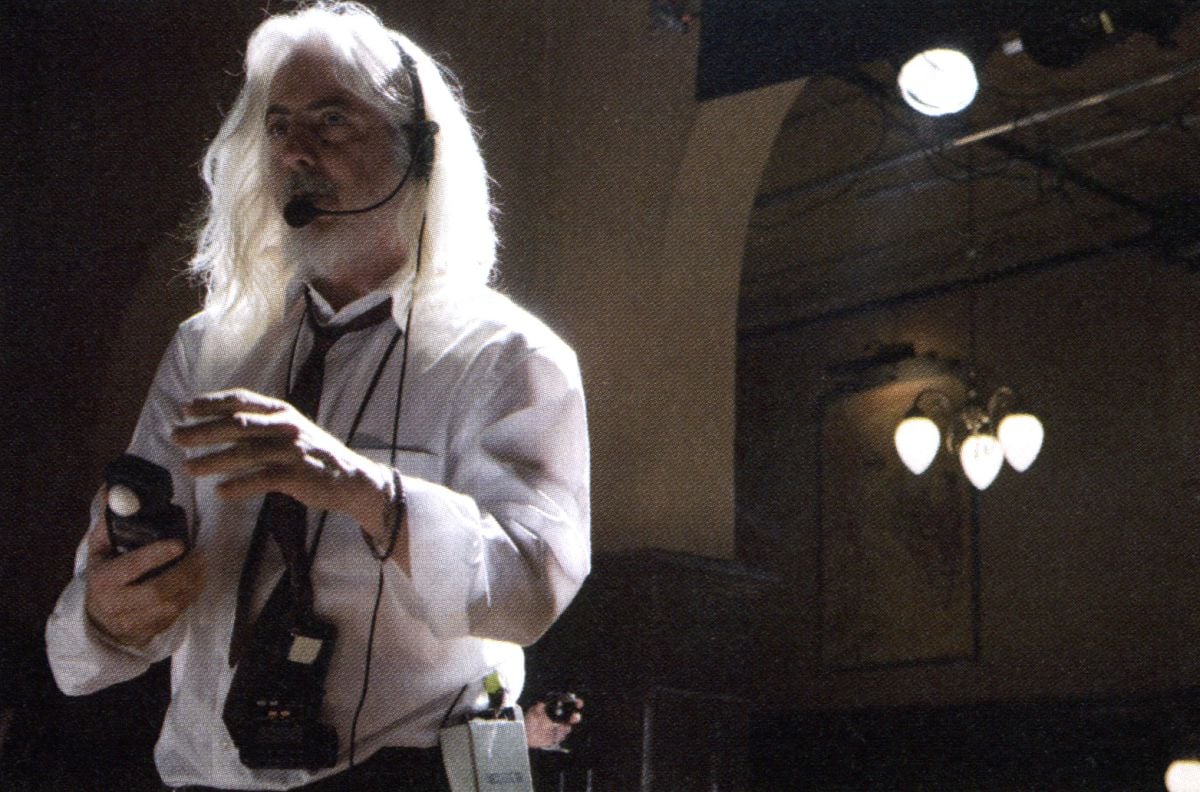

World War II is the backdrop for Quentin Tarantino’s stylized revenge fantasy, shot by Robert Richardson, ASC.

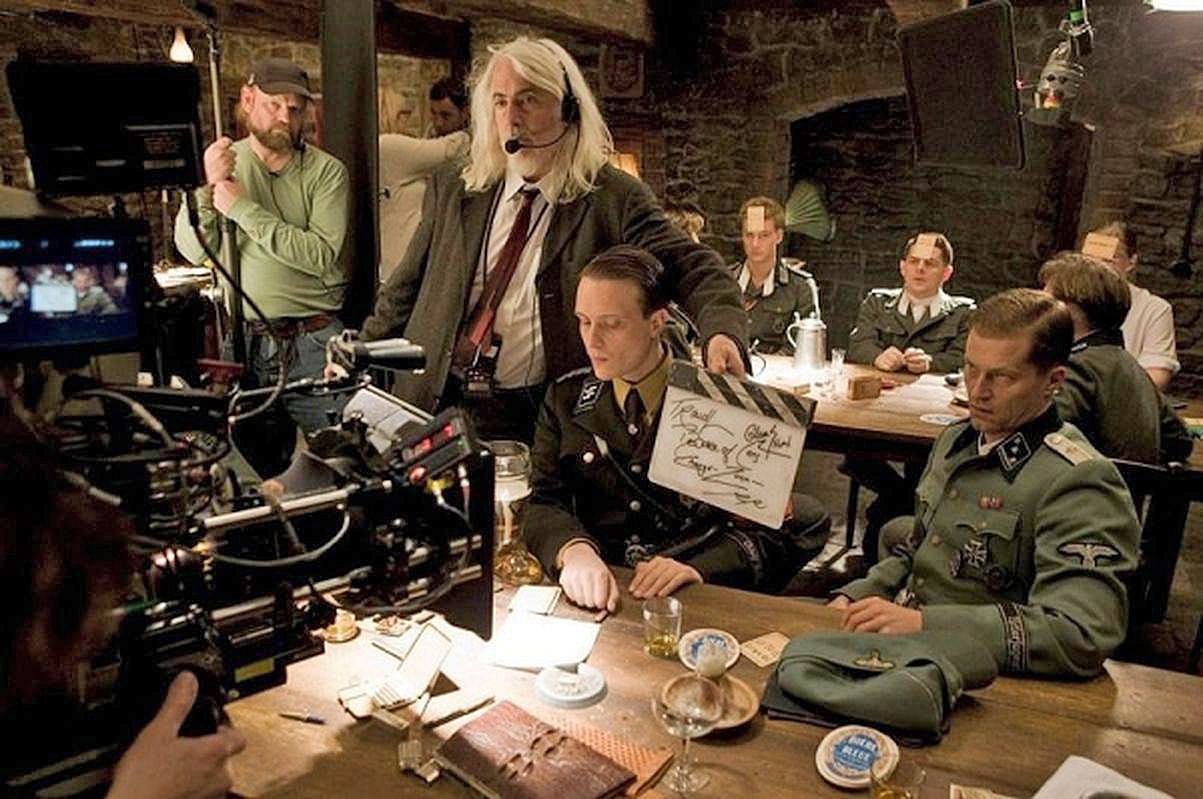

Unit photography by Francois Duhamel, SMPSP

During a press conference at this year’s [2009] Cannes Film Festival, Quentin Tarantino maintained, “I am not an American filmmaker. I make movies for the planet Earth.” The director and his crew were at the festival for the world premiere of his latest creation, Inglourious Basterds, whose intentionally misspelled title is the first of many twists from a production that combines a European milieu with its earthling auteur’s stylized sensibilities.

The World War II saga was shot mostly at Studio Babelsberg near Berlin, with an international cast that includes Brad Pitt, Mélanie Laurent, Diane Kruger, and Christoph Waltz. One of Tarantino’s innovations was to allow the characters to speak in their native tongues; the subtitled film skips easily from French to English to German, and the mastery of foreign languages, the subtlety of accents, and even body language are all important plot points.

Inglourious marks the third collaboration between Tarantino and Robert Richardson, ASC following Kill Bill: Vol. I (AC Oct. ’03) and Vol. II. Prior to teaming with Tarantino, Richardson shot 11 films for Oliver Stone before establishing an ongoing rapport with Martin Scorsese (for whom he recently shot the forthcoming thriller Shutter Island). Richardson has won two Academy Awards — for JFK (AC Feb. ’92) and The Aviator (AC Jan. ’05) — and notched three other Oscar nominations, and he has been nominated for eight ASC Awards. [He was honored with the ASC Lifetime Achievement Award in 2019.]

The story unfolds as a series of chapters that weave three subplots united by one very bad guy, Gestapo Col. Hans Landa (Waltz). In an opening that evokes Spaghetti Westerns, Landa and his posse of Nazis drop in on a French farmer and his family. While soldiers and the family wait outside, Landa methodically asks the farmer increasingly pointed questions about the whereabouts of missing Jewish neighbors during a cat-and-mouse sequence that builds inexorably to violence.

After Landa kills her family, Shosanna (Laurent) escapes to Paris, where she runs a movie theater and meets top Nazi brass. When Shosanna learns that her theater has been chosen for the VIP premiere of a Nazi propaganda film, she sees an opportunity for revenge.

Elsewhere in France, a unit of Jewish-American soldiers, led by hillbilly Aldo Raine (Pitt), lurks behind enemy lines terrorizing Nazis with the threat of mutilation, scalpings and executions by baseball bat. Tales of these “Basterds” eventually reach Hitler, who throws a fit.

Meanwhile, in London, the British high command hatches a plot to blow up the movie premiere. German-speaking agents are sent to a cellar tavern called La Louisiane, where they meet with a glamorous German actress (Kruger) who is actually a British secret agent. In a lengthy scene, the agents exchange pleasantries with a party of drunken German soldiers, and then with a suspicious Gestapo officer, before engaging in a climactic shootout.

As always with Tarantino’s films, Basterds is rife with cinematic references. Indeed, much of the action takes place inside the movie theater during the projection of a black-and-white “film-within-a-film” directed by Eli Roth; the production even arranged for lead actress Laurent to learn how to run a film projector. The final sequence gathers its main characters at the big movie premiere, leading to a spectacular, surprising conclusion followed by an ironic epilogue.

In discussing Tarantino’s approach to moviemaking, Richardson agrees that the director qualifies as a film “purist.” Richardson’s longtime camera assistant, Gregor Tavenner, concurs, noting that Tarantino eschews the “video village” found on most contemporary sets. “The only video monitor on the set is the small one on the camera,” says Tavenner. During takes, Tarantino stays next to the camera, near the actors. If there is a dolly move, he climbs along for the ride, looking at the actors and glancing at the small Transvideo monitor on the camera to check the framing.

Tarantino favors shooting with a single camera, going against the trend for two cameras, which often necessitates lighting and staging compromises. “You get such a handcrafted movie,” Tavenner enthuses. “The actors know they’re going to do a lot of setups because it’s only one camera, but they get to perfect their craft. The camera rolls for as many takes as necessary to perfect each shot, and it’s a real joy and a pleasure.”

Tavenner explains that the director enforces a quiet set: “Quentin creates a beautiful environment for the actors to perform in. The crew is trained to be so respectful.” Tarantino bans cellphones from his set; a security person at the door collects all such devices. Tavenner recalls a tense moment when producer Harvey Weinstein came to visit the set and the guard asked for his phone. There was a moment’s pause, but Weinstein finally handed it over and nodded to his assistant, who then handed over four more. “Everybody cheered,” Tavenner recalls with a chuckle.

Richardson’s longtime gaffer, Ian Kincaid, describes another Tarantino tradition on the set: every 100 cans of exposed film are celebrated on the spot with a glass of champagne for each crew member. “Quentin is very gracious. He’ll say, ‘Hey, everybody gather ’round. Let’s celebrate another 100 rolls!’ — even if it’s 11 in the morning.” During production, Tarantino also arranged for evening crew screenings of features he personally selected.

Part of the period style of Inglourious Basterds is created via dolly and crane movements. “In a way,” says Tavenner, “it’s a classic style. There’s maybe one Steadicam shot in the whole film.” A Technocrane was used sparingly (once to sweep across the audience in the movie theater), but the bulk of the crane shots were done with Richardson riding a one-person crane made by Grip Factory Munich, allowing for more organic, less automated movements than a remote head would produce. “I often use a crane as a dolly when the space allows, because it allows for greater movement,” the cinematographer notes. “I can also do a tracking shot without seeing the dolly track in frame.”

Inglourious was shot with Panavision anamorphic Primo and G-Series lenses, as well as the company’s new anamorphic zooms and a “Panavised” Cooke. “The Primos held up the best in terms of overall resolution,” Tavenner asserts. “You have a sweet spot between T2.8 and T4. If you can close those lenses down a stop, you gain quality that is well worth it.”

Richardson explains that Tarantino’s propensity for wide-angle lenses and centered framing give the film a contemporary, original feel. “I could have shot the movie with just the 35, 40 and 50mm,” he says. “That’s not what you would do on an old-fashioned movie, though; this lensing is more modern.

“Quentin and I will have these interesting little battles while I’m composing a shot,” Richardson continues. “I naturally move to one side or the other, especially when shooting anamorphic, whereas Quentin enjoys dead-center framing. For singles in particular, we’re just cutting dead-center framing from one side to the other, with the actors looking just past the barrel of the lens.”

Part of the distinctive look of Inglourious Basterds stems from its disregard for pure naturalism and lighting motivation, which also contributes to its impressionistic period feel. For example, the look of the opening scene in the farmhouse is defined by hot, hard daylight that shines down onto a table, bouncing to illuminate the two characters. Although one can imagine a skylight above the table, there is no clear motivation for the farmhouse lighting. “I don’t believe there always needs to be a motivation for a light,” says Richardson. “Sometimes you have to light for what you feel the sequence is.”

He explains that he avoided a source-y approach to the scene (i.e., having the main source come through the windows) in part because this “would have put a lot more light on the background. Here you feel the daylight on their faces but the background is relatively dark. The room was tiny and the source was isolating them in that small space.” He points out that the table bounce is also adapted to the action of the scene: Landa fills out his paperwork, while the farmer has a tendency to look down. “I felt it was important to have light in their eyes and to always have that bright spot available to the iris if so desired,” he says. The toplight source also gave the actors the opportunity to play with the light by moving in and out of the shadows, and it enabled Tarantino’s camera staging, which involved several wide-angle dolly moves around the table. “When the camera started on one side and ended on the other, there were very few places to get a light in,” Richardson observes.

The cinematographer would often add a soft fill light during the scene, and he felt free to adjust the direction of the top keylight from shot to shot.“When I had the opportunity, I would add a level of bounce, and I would move the toplight to one side or the other to help the dark side move toward camera. I prefer to have the face lit from the opposite side — not backlit, but ¾ — and I want the dark side toward my lens as often as possible; there’s something I like aesthetically about that choice. I’m willing to flip a key in a sequence to accommodate that.”

Tarantino told Richardson he wanted to see the landscape through the windows of the farmhouse, which required the quick changing of ND gels on the windows to adjust for the changing weather outside. Kincaid notes, “We’d sometimes have to bring the light way up inside” to balance with the exterior view. All of the scene’s sources were daylight-balanced HMIs, and inside, the main overhead source comprised Par 1.2Ks rigged in an attic above the table. Most of the lights were gelled with ¼ CTO to lend the “daylight” a slight warmth.

Large sources outside provided some soft light and an occasional touch of hard light inside. These external sources included 18K Arrimax HMIs on turtle stands bounced up on big muslin frames, a 12K Par through the door, and a 6K Par through a window to create a small spot of sunlight on the wall.

Kincaid confirms that there was no lighting whatsoever, not even a passive bounce, during the 100' tracking shot of Shosanna running away in profile at the end of the sequence. Achieving this shot was simply a matter of choosing the right moment to film against the naturally soft backlight of the northern sky.

Filming began on location at a farmhouse in northern Germany with an initial plan to capture mostly exterior shots before moving to a soundstage for the interiors. But Tarantino quickly decided to start shooting the dialogue inside the house before continuing to shoot the same scene on the Babelsberg stages near Berlin, creating a challenge in terms of lighting continuity because the location and stage footage had to cut together seamlessly throughout the 25-minute sequence. To maintain continuity, the location lighting was duplicated in Babelsberg, and Richardson decided to use HMIs on the soundstage, “which we never do,” says Kincaid. For the windows, Richardson used greenscreened plates when necessary, or painted backdrops masked with black net when the windows were less “present” in the frame.

The roomy soundstage allowed for bigger bounce fills than the location, but the principle was the same: “muzz and muzz.” Kincaid explains that Richardson eschews “plastic” diffusion or bouncing material like beadboards or Griffolyn in favor of cotton muslin or real silk. A “muzz and muzz” soft source involves hard lights bounced off muslin and then diffused through muslin again. The sides of the setup are covered with black material to prevent spill, creating a pie-shaped, soft light box. Richardson explains his affinity for muslin by noting it “has a more natural feel on the skin. I don’t feel as many highlights coming back,” whereas plastic materials give a “shine off of makeup or skin.”

Richardson claims that the muslin-bounced diffusion lends a unique quality to the soft source. “It’s the quality of the wrap of the light. I don’t feel the shadow of the source. I enjoy the way the light moves across the face.” Because the soft light has to be cut and flagged, the cinematographer usually tries to obtain the largest possible diffusion surface for the location. For example, when Pitt’s character interrogates a Nazi in the ravine scene, the bounce is a 12-by, but for tight interiors, the cinematographer will sometimes just staple a 4' piece of muslin bounce to the wall.

For a few scenes in Inglourious, Richardson uses a passive bounce as a key. A 12K provides most of the lighting for a brief but memorable scene in which Shosanna wields a hatchet and threatens a film developer positioned on a table. The hard source backlights Shosanna and her accomplice and then bounces off the table to provide a soft key on her face. The lighting is completed by a practical above and a 12K positioned on a Condor outside a window.

A similarly elegant use of hard light and bounce can be seen toward the end of the film when a smitten German soldier barges into the projection booth and confronts Shosanna at the doorway. Shosanna is backlit by a 20K positioned farther back on the set, and the soldier acts as her moving bounce: a strip of muslin was pinned to him off-camera. “Depending on how close she moves to him,” Richardson comments, “there is a movement [in the light] and a lighter and darker quality on her face.” A hint of red bounce also comes from Shosanna’s red dress. On the reverse shot, a similar setup lights the German, with a 12K bouncing off of the red dress. Other backlights were added to extend this effect once the actors move further inside the booth.

Richardson used a mixture of hard and soft sources for a beautiful scene on the top floor of the theater. As Shosanna prepares for the fateful premiere by applying her makeup, a 20K shines in through a circular window to provide a searing backlight. In front of the mirror, her face is keyed by a warm, soft source com¬ prising a cluster of small, tungsten “golf ball” bulbs dimmed way down and diffused through muslin. Kincaid explains, “The muslin lends a creamy feel to her skin. When we’re shooting a beautiful woman, we’ll go muzz-muzz. Generally, the front is bleached muslin and the back is unbleached. Unbleached muslin has a tighter weave; it’s a nice, rough surface, so it has no sheen. It’s a bit erratic, but it softens the light, and then the bleached muslin in front unifies it.”

Kincaid reveals that Richardson often uses rows of dimmed tungsten bulbs with diffusion to create soft sources that can fit in tight places. “On this film, we used soft frosted bulbs on wires, bunched in balls, attached to squares of wood and even draped around the camera,” says the gaffer. A variation of this technique was applied for a scene in which Shosanna is whisked off to meet Goebbels in a swanky French restaurant. Their encounter was shot in a private dining room at Berlin’s Einstein Cafe. Rows of tungsten bulbs were suspended from the low ceiling and diffused with muslin to create a soft top source, which was supplemented by several Chinese lanterns and a Par can throwing a pool of hard light down onto the tablecloth. Kincaid notes that Richardson frequently uses lightweight Par cans. “You can cluster them, and we use them for accent lights, for narrow backlight, and often for bouncing,” he says.

The long scene in the La Louisiane tavern posed one of the show’s biggest lighting challenges. Ten characters meet around two small tables in the cramped basement bar. The three British agents try to talk their way out of the tavern, leaving one table of drunken Germans and then accepting a round of drinks with a suspicious Gestapo officer. The tension rises until the scene explodes in a shootout.

The tavern set had very low ceilings and little room in which to maneuver. Richardson deadpans, “For all intents and purposes, it was a practical location built on a stage.” Kincaid adds, “We said to ourselves, ‘Okay, this is like the trailer scene in Kill Bill.

Quentin wants to create the feeling that nobody’s getting out of here easily.’” Complicating matters further, the actors frequently move from seated to standing positions.

After trying and rejecting inframe practicals as too cluttered, the crew attached rows of tungsten bulbs to the ceiling, adding two layers of muslin beneath them to create a soft base light. The headroom was so tight that the bottom layer of muslin had to be removed when actors stood. Richardson then decided to add Par can toplights and bounced backlights as the shots progressed, reflecting the scene’s mounting tension. “Slowly, as the scene evolved, I moved from the soft top and started adding hard lights off the table to increase the contrast. I also began bringing in soft backlights to separate actors from the background. I just felt this need to do it as I went along, but I tried not to do it in an obvious manner so the audience wouldn’t be aware of it.”

Although the transition is subtle, Richardson confesses that he wondered at the time whether altering the light was “a gigantic error.” Kincaid concedes, “We were very busy in there; every setup was a new challenge. We have a saying, though: ‘Pressure makes diamonds.’”

When the shootout starts, the lighting changes dramatically, with beams of hard light shining through the smoke and gunfire. Tarantino punctuates the scene with a few of his signature snap-zooms into Germans firing their weapons. The timing of the shootout feels realistically rapid, without the extensive high-speed work that has become a convention in contemporary action films. The lighting for the dramatic climax in the movie theater involved a series of 6K and 9K Maxi-Brutes hung from the ceiling with black skirts and silk frames. A fire effect was created mostly with real fire generated by an extensive network of gas pipes, supplemented by red gels on the Maxis.

Richardson did the digital intermediate for Basterds at EFilm with colorist Yvan Lucas, and the colorist says he did the color correction “the old-fashioned way,” starting from the qualities Tarantino and Richardson liked in the workprint made by Arri Munich during shooting. While he was timing the tavern scene, Lucas recalls, “Bob said, ‘Yvan, I know you come from film, so you’re going to match the faces, right? You’re not going to do it like the video timers, who match the backgrounds?’ His point was that faces are what jump out at you, and that was the big idea of the film: to work the old-fashioned way, by matching faces, and then seeing what we could do with the backgrounds if there were any problems.”

Asked how Richardson’s penchant for strong hard light impacts the digital grade, Lucas notes that he sometimes uses Richardson’s highlights to find the timing of a shot. “I’ll often start with the faces, but I can also find my density value in relation to the strong highlight. It’s like a visual reference that shows me where I have to place the shot. If the white is too bright, it’s not very pretty. By adding density, the white remains very overexposed and very strong, but it gets more body. In fact, there is very little choice in timing. There is one value that’s really right. Often when Bob sees what I’ve prepared for him, he doesn’t ask for density changes because I’m already where he wants to be.

“Bob has a very particular way of lighting a face — it’s very chiseled,” Lucas continues. “That allows me to go to a density value I would never dare use on another film. There is a gradation in the grays of the shadows that I can work with. His lighting allows me to go to a darker and very interesting density value without smothering the blacks.” For example, the colorist adds, referring to the scene in which Shosanna stands at the window before applying her makeup, “because the backlight is very strong, there is detail in the blacks. Although she is in the shadows, her face is delineated. When you add density, you see the cheekbones... but with this gradation. It’s very beautiful, and it’s due to the very hard light.”

Reflecting on his work, Richardson muses, “When I’m shooting, I don’t sense the passage of time. I start and finish the sequence, and I don’t recall the majority of what takes place in between unless I have a tremendous problem or I’m trying to rectify something in the middle of the sequence. Nothing exists except for that moment. The closest thing to it is when I jumped out of an airplane and parachuted to the ground. I don’t recall anything after jumping ... until my chute opened.”

2.40:1 Anamorphic

35mm Panaflex Millennium; Arri 435

Panavision Primo, G-Series lenses

Kodak Vision2 200T5217, Vision3 500T 5219

Digital Intermediate

Printed on Fuji Eterna-CP 3513D