The Japanese Method for Ran

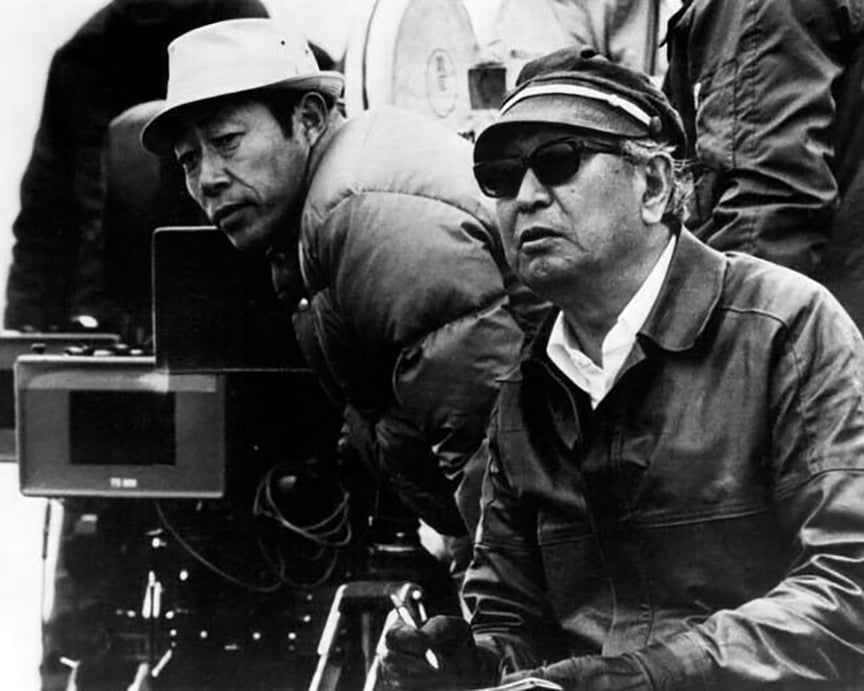

Legendary director Akira Kurosawa prefers to use multiple cinematographers on all of his films, dating back to 1954's The Seven Samurai.

This article originally appeared in AC, July 1986. Some images are additional or alternate.

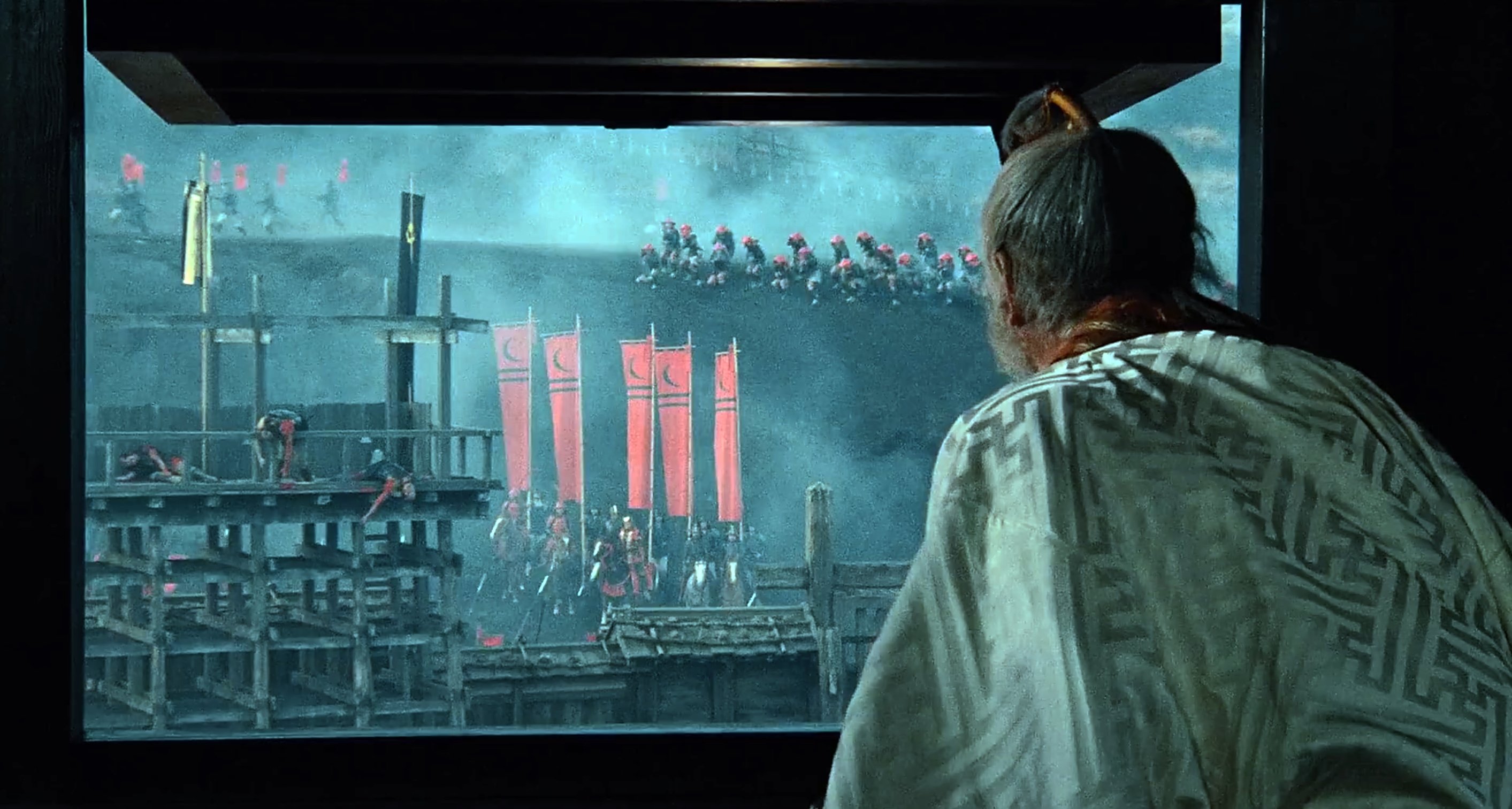

Some scenes only nature can paint, and few directors understand that better than Akira Kurosawa as he waited patiently for the weather to change on the slopes of Mt. Fuji. He was making Ran, an epoch movie set in feudal Japan documenting a tragic struggle for power between an aging warlord and his three sons.

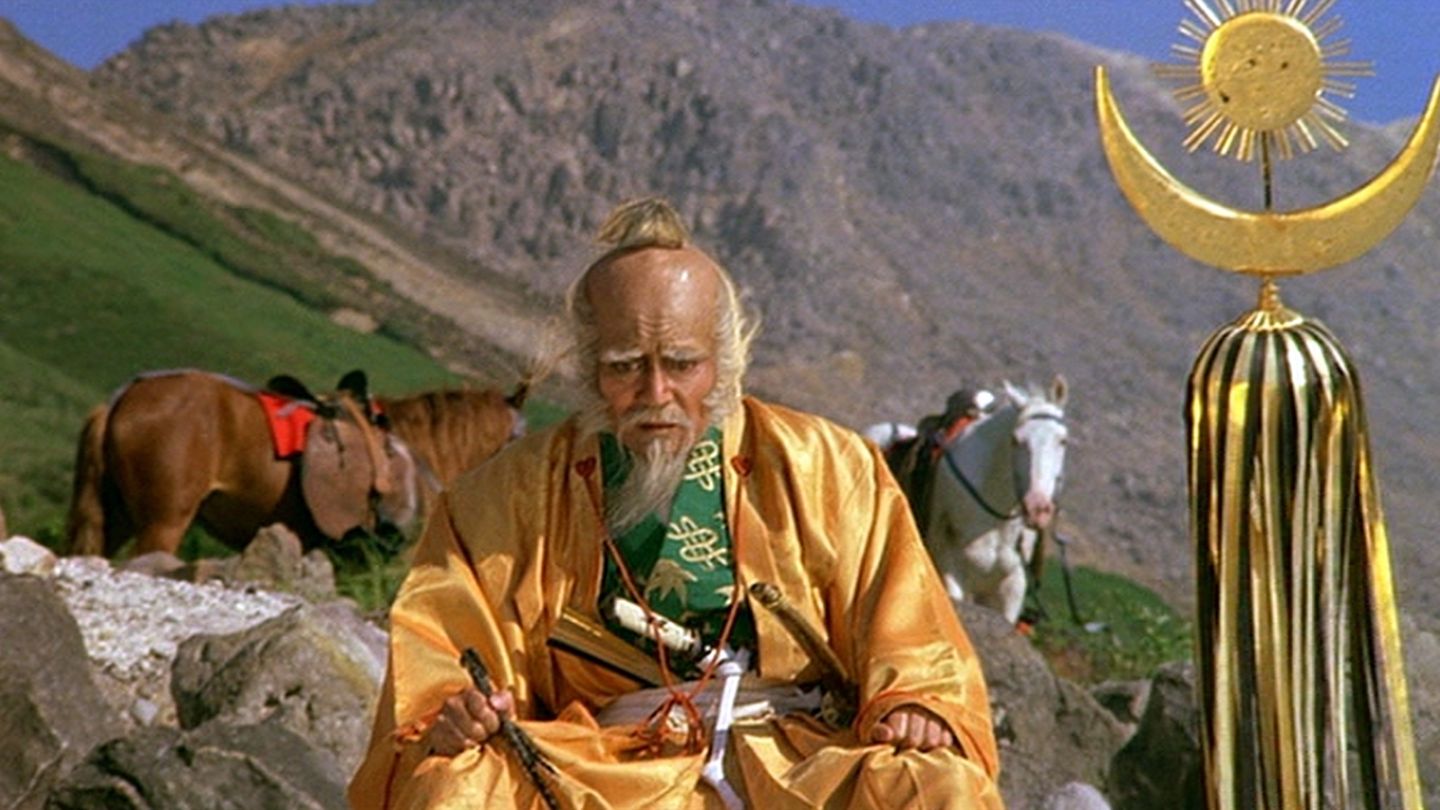

The warlord, or great lord, as he is called, has spent his lifetime stitching together an empire stretching over vast plains framed by snowcapped mountains. The story begins when the great lord unexpectedly announces that he will retire with only a small entourage, and he appoints his oldest son as his successor, ordering the others to swear fealty.

Discord results almost immediately, and the fabric which the great lord has spent his lifetime weaving begins to unravel. It very quickly becomes evident that there is a severe price to pay for the crimes that he has committed in his lust for power.

“Mr. Kurosawa and I [both] dislike special camera techniques... Fundamentally, the camera is not a player; it is there to record all that ought to be recorded and nothing more.”

— Takao Saitô, JSC

Ran is the first made-in Japan feature film in the 58-year history of the Academy Awards to earn an Oscar nomination for cinematography. (In 1970, three Japanese cinematographers shared an Oscar nomination with Charles Wheeler, ASC for Tora! Tora! Tora!)

Critics have compared Ran to Shakespeare's King Lear. There are obvious similarities in story and motivation of characters. However, as a motion picture, Ran is distinctly Kurosawa's visualization of a story which he obviously saw with great clarity in his own mind before the first frame of film was exposed.

In this context, Kurosawa has said, "To create is to remember."

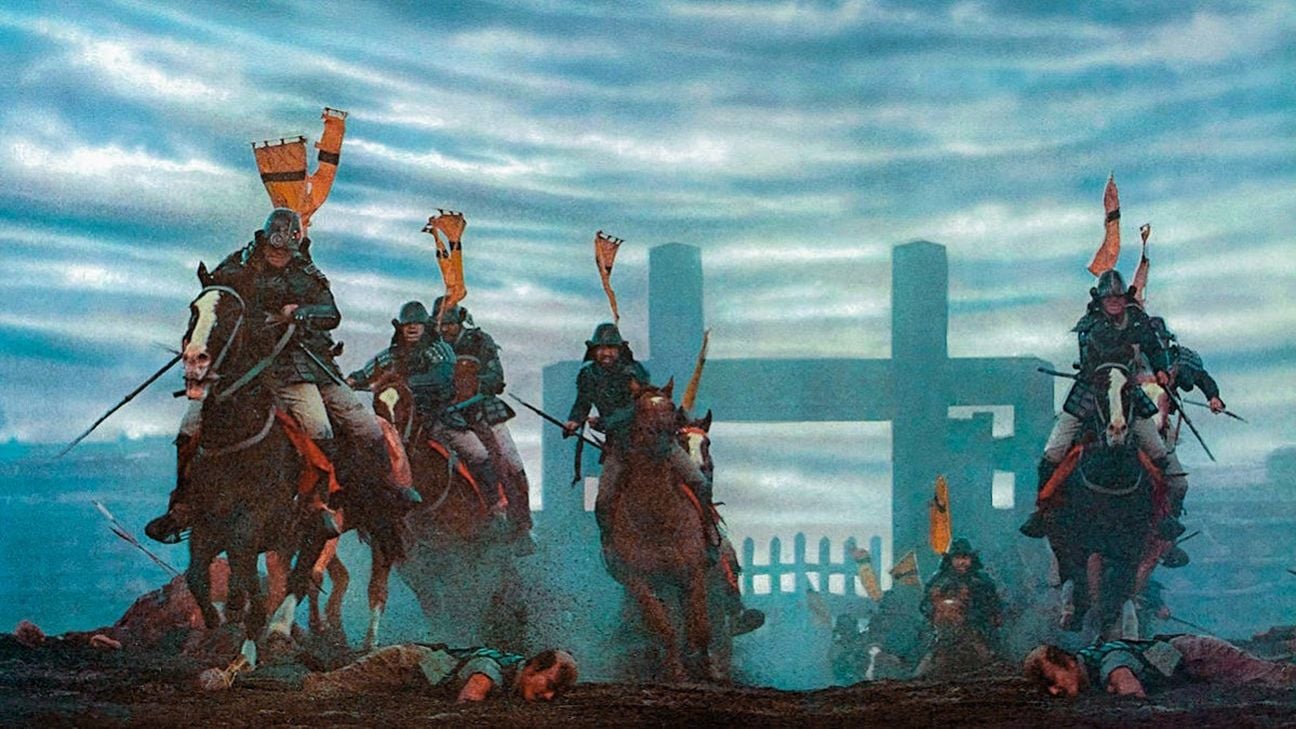

There were times during production when Kurosawa stoically meditated while waiting to shoot a complex battle scene involving hundreds of extras, including considerable action involving cavalry. He was waiting for nature to provide the background that promised to match his vision of the setting for a pivotal scene.

Sometimes the window of opportunity was very small, and it took a dedicated as well as disciplined cast and crew to respond. In those situations, it is said that Kurosawa could shoot seven battle scenes in the time that it might take another director to film a poker game. Kurosawa was also uncompromising in his attention to the smallest details that contributed to the overall illusion.

If that required re-shooting a scene, which was almost perfect, no quarter was given. In that sense, Ran was filmed one frame at a time. "We had some 200 very precise drawings before shooting started, 100 for the hell scene alone," says lead cinematographer Takao Saitô, JSC.

The drawings, which Kurosawa continued to produce throughout the filming process, were very specific right down to actors' expressions and the subtlest of colors. The cinematographer's tasks were to translate the illusion which Kurosawa had envisioned when the drawings were made, and to film as faithfully as possible.

Notice that we said cameramen — plural. Three cameramen participated in the filming of Ran: Saitô; Asakazu Nakai, JSC; and Shoji Ueda, JSC. As the letters following their names indicate, all are members of the Japanese Society of Cinematographers, and Nakai is a past director of the organization.

This is not an atypical situation, especially in the case of Kurosawa, who has used multiple cameras in production ever since he directed the last half of The Seven Samurai in 1954. According to Saitô, who has frequently worked with Kurosawa during this period, the purpose is to secure enough coverage from various angles and focal lengths to cleanly and effectively link action during the editing process.

There is an interesting contrast here to Western filmmaking methodology. During the production of Ran, as is the case with all of Kurosawa's work during the past 20 years, the three photographers each had responsibility for a specific camera.

They worked both as colleagues and in a teacher-student relationship with each other, and with Kurosawa, as they have for many years. Kurosawa emerged as a director some 40 years ago, and he created more than 30 films during this period. Nakai, who, like Kurosawa is 75 years old, did his first film with the director in 1946 — Waga Seishun ni Kui Nashi [No Regrets for Our Youth].

In all, Nakai has been cinematographer for 10 of Kurosawa's films, including Ikiru (1952), Seven Samurai and Dersu Uzaia (1975). He has also worked on various other famous features, including Tadashi Imai’s Aoi Sanmyaku (1949) and Kimisaburo Yoshimura’s Itsuwareru Seiso [Clothes of Deception] (1950). The Mainichi Film Concours awarded Nakai the Cinematography Prize for Norainu [Stray Dog] (1949) and Aoi Sanmyaku. He has also received the Japan Film Technique Award for Ikiru and The Seven Samurai, and the Film World Special Prize for Itsuwareru Seiso.

Saitô started his career as an assistant to Nakai on Kurosawa's film Subarashiki Nichiyobi [One Wonderful Sunday], in 1947, when he was 28 years old. He was the "B" cameraman on Ikimono no kiroku [I Live in Fear] in 1955. Saitô advanced to main cameraman in 1962, when he photographed Sanjuro Tsubaki with Kurosawa.

Ran is Saitô’s sixth feature film with Kurosawa as main cameraman. The others were Heaven and Hell (1963), Redbeard (1965), Dodes'ka-den (1970) and Kagemusha: The Shadow Warrior (1980). Sanjuro Tsubaki won an award for cinematography at the Asian Film Festival, and Heaven and Hell won the best cinematography award from the Hokkaido Shimbun newspaper.

Ueda started his career when he was 23 years old, working as an assistant to Saitô on Sanjuro Tsubaki and other films. He was the "B" cameraman on Kagemusha.

Ueda was the "B” cameraman for Ran, and Nakai was the "C” cameraman and backup. The juxtaposition of cameras varied depending upon the scene and situation. Sometimes they were set up at wide distances in order to cover scenes from different visual perspectives. Other times, three cameras were tightly clustered focusing on different aspects of a scene, or looking at the action through different focal lengths.

Typically, Saitô was responsible for the overall scene, Ueda for actors' movements, and Nakai for expressions. Another example would be the filming of the battle scene between the armies of the second and third oldest sons. Saitô's camera was set up on a nine-meter-high platform overlooking the meadow where the battle scene was filmed. He covered the entire battle with a 55mm lens.

Ueda's camera was on a slightly lower platform, seven meters high, but in the same position. The cameraman focused on the third son's force through a 150mm lens. Meanwhile, Nakai's camera was set up in a forest 500 meters from camera "A,” and it was used to cover the two sons' armies with a 100mm lens.

Saitô was involved informally (which means not under contract) in preproduction planning stages for Ran while he was working on Kagemusha. Location scouting began during the autumn of 1982. Saitô was responsible for site location and shooting tests.

''At first, we decided on Hokkaido as the main location, which was the same site as Kagemusha," says Saitô. However, various difficulties emerged, including an inability to get permission to shoot in the large field used for Kagemusha, a lack of a sufficient number of available horses in the area, and a decision by Kurosawa that the mountains and rivers in the Hokkaido location weren't ideal for the settings he envisioned.

Further research revealed that Kyushu would be a more appropriate main location for all of the above reasons. In addition, Himeji and Kumamoto castles, both historic sites, provided ideal settings both as exterior backdrops and for selected interiors. A third castle was constructed to meet specific production objectives.

Ueda began working on Ran in February, 1983, and Nakai joined the production team in May 1984 when shooting actually started.

Three Panaflex Gold cameras were used mainly with 25mm to 250mm zoom lenses. The cameras were each equipped with a Panavision electric spray deflector, a device which is fitted on the front of the lens to prevent rain or other water drops from splashing on the glass.

Mr. Kurosawa does not like wide-angle lenses," says Saitô. He also avoids zooming, though zoom lenses are on the cameras most of the time. Instead, the zoom lenses are generally locked down at a specific focal length, very often 75mm.

Then, why use zoom lenses? "To assure very precise color balancing," Saitô replies. The use of color is very important in developing the visual style of Ran, and Kurosawa wanted to avoid any possibility of subtle variations which could result from using various focal-length lenses.

Other production tools included a Mitchell Mark II, which was used primarily for slow-motion work, 400, 600, 800 and 1000mm lenses, and a combination of arc and HMI lighting elements.

Around 100,000 feet of Eastman color negative film 5247 and Eastman color high speed negative film 5294 were used for original photography with the latter employed for interiors and night work.

Except in those situations where very subtle exposure decisions were required, the three cameramen left it to their assistant to handle and coordinate exposure calculations to assure that footage from the cameras could be easily intercut.

Saitô says that Kurosawa al ways uses Eastman color negative film because of its consistency in processing, ease of handling during editing, and the comparative stability of colors and images during storage.

Processing was handled by Imagica, in Tokyo, (formerly Toyo Genzo Sho) by the same person who did color timing for Kagemusha. Saitô notes that was important because the timer had become very familiar with the visual intentions of Kurosawa and his cinematographers. "We were very careful to avoid color balancing deviations between the three cameras, yet this was unavoidable because of the use of smoke and the presence of fog in some scenes," he says. "Imagica was very helpful in these cases."

Saitô continues, "As regards color and compositions we were guided by Mr. Kurosawa's sketches . . . [he] divided the three brothers into yellow, red and blue camps, and devised special costumes based on color schemes found in Noh. We tried to be faithful to these colors, and also tried to preserve the true qualities of the subjects — the textures of their hair and clothing, etc. We meddled very little with the colors, but we sometimes used colored reflectors for character delineation."

In addition to the sketches, the cameras were always present during rehearsals, so the three crews were able to easily and quickly adjust to any changes in movement.

“We are extremely pleased just to be nominated, for we never even expected that to happen.”

As for photographic style, Saitô says, "Mr. Kurosawa and I [both] dislike special camera techniques... Fundamentally, the camera is not a player; it is there to record all that ought to be recorded and nothing more. I tried to photograph scenes so that they were easy to watch and understand."

Because of the nature of the story, Saitô adds, there are many scenes where characters are photographed either full body or waist up.

As much as Ran is a story about the people, including the great lord, his sons, and others affected by their interactions, it is also a story about the land. Kurosawa's direction and the photography gives audiences an intimate feeling for both.

On the Oscar nomination, Saitô comments: "We are extremely pleased just to be nominated, for we never even expected that to happen. I think it is because we were fortunate enough to have a good story, and also to have had a very cooperative staff... I would like [this] to be a step to the future."

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.