John Bailey, ASC: Inside the Outsider

The cinematographer discusses his career behind the camera, his love for international cinema, his tenure as president of The Academy and what it takes to succeed in a very difficult business.

Editor’s note: John Bailey died at the age of 81 on Nov 10, 2023. A full memorial piece will soon be available.

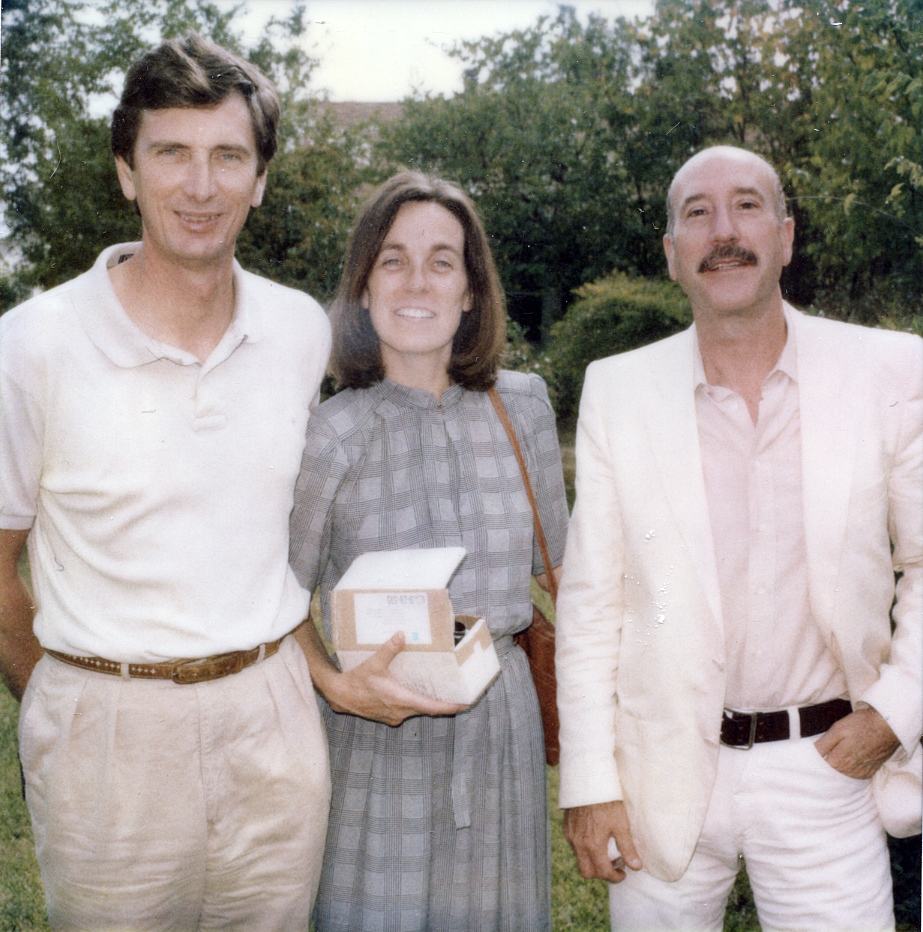

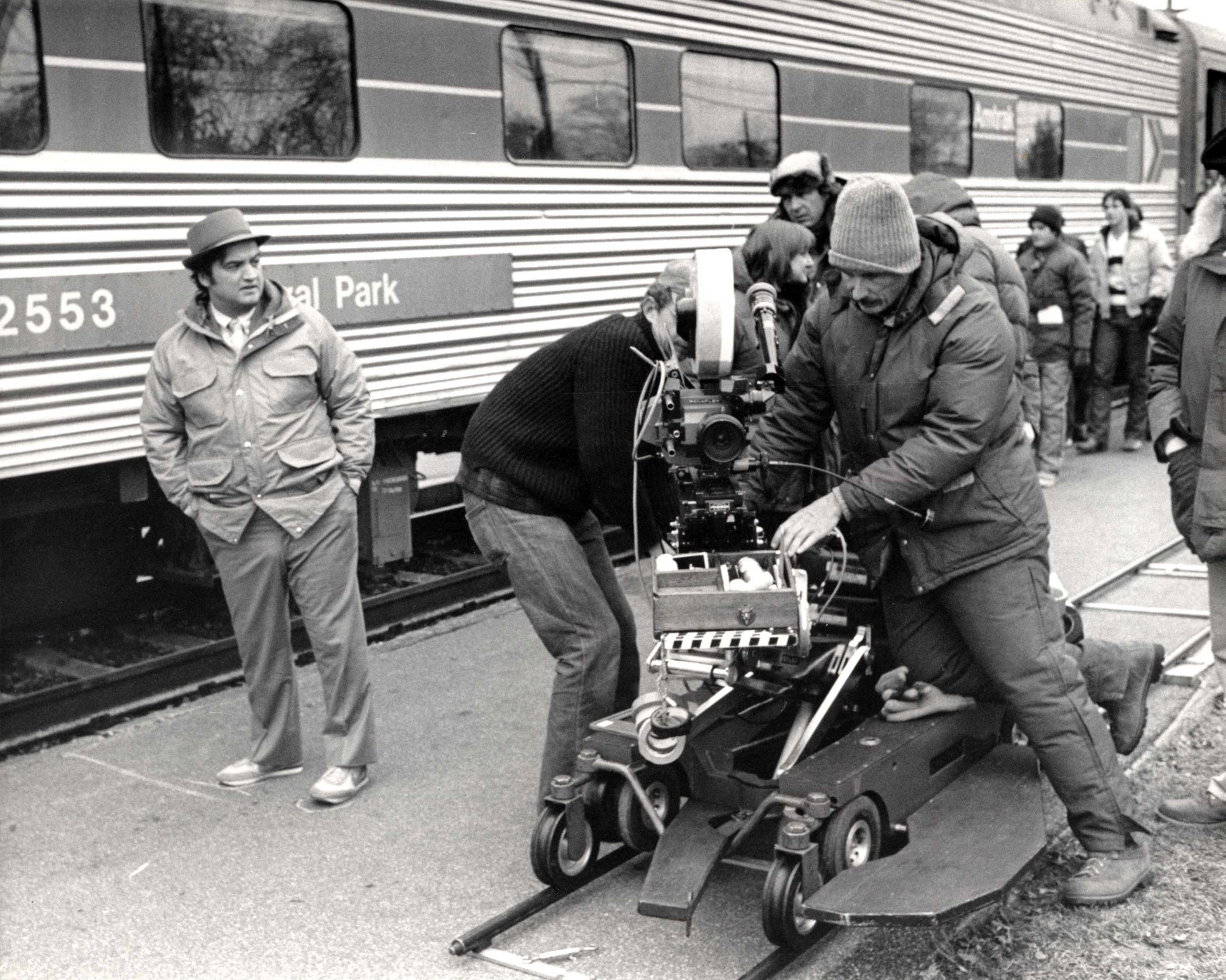

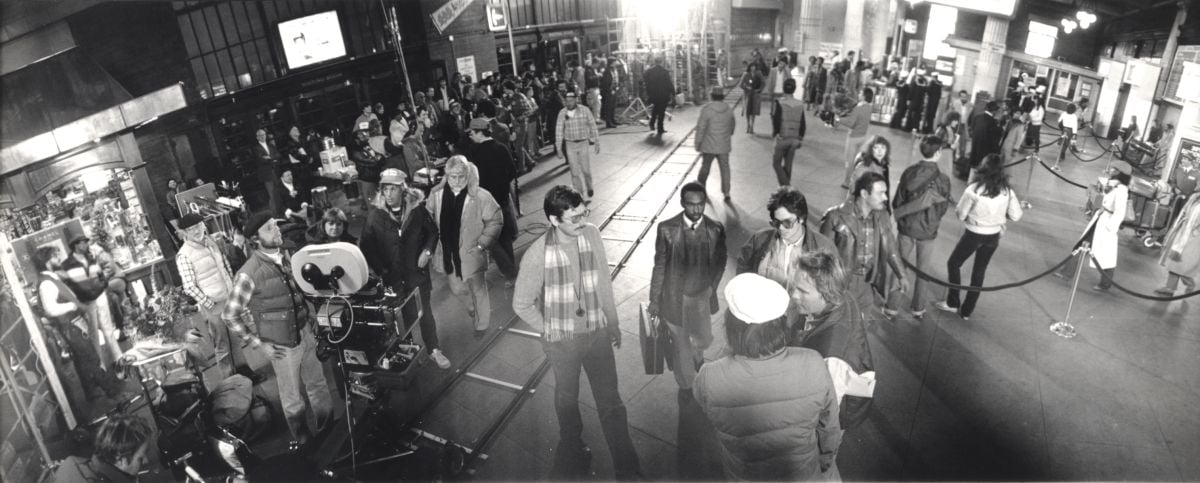

During the recent International Film Festival of the Art of Cinematography Camerimage, held in Torún, Poland, John Baily, ASC was honored with their Lifetime Achievement Award, presented with the trophy by Richard Gere. The actor starred in one of the cinematographer’s early breakthrough pictures, American Gigolo (1980), directed by Paul Schrader.

In 35 years, Bailey has amassed an eclectic body of work that runs the gamut from dramas and action to comedies and Westerns. Perhaps because of that variety, his cinematography doesn’t show the stamp of a single cinematic sensibility, but instead reflects as many different approaches as there are credits to his name. “I’ve never read a script to try to find photographic opportunities,” Bailey offers. “I look at the emotional value to see if I’m moved.”

Born in Moberly, Mo. and raised in Norwalk, Calif., Bailey’s background was blue collar, but his parents had an abiding respect for education and did all they could to ensure that their son would have the opportunities they hadn’t.

While attending Pius X High School, Bailey was guided toward college-prep courses. In his senior year at Loyola University, he was accepted to the University of Southern California’s School of Cinema. His studies opened his eyes, particularly to the works of filmmakers such as Ingmar Bergman and Michelangelo Antonioni. He aspired to be a film critic.

To critique cinema from a more technical point of view, Bailey enrolled in a cinematography course. One of his first assignments was to shoot a photographic study using a single roll of film. Bailey chose to shoot the routine at a hamburger stand, taking photos as the cook flipped burgers and the patrons ate. With some residual embarrassment, Bailey recalls, "The frames were so overexposed that there was barely an image! I’d misread the meter. I did whatever I could to make prints and brought them to class.”

The teaching assistant happened to be future ASC member Woody Omens. “I was thoroughly chagrined by these photographs, but Woody said, ‘Mr. Bailey here has done something interesting. He has chosen to make it very high key. It’s almost as if Richard Avedon had photographed a hamburger stand!’ I saw this as a disaster, and Woody put a beautiful, supportive, positive spin on it. Woody is the reason I had the courage to pursue photography."

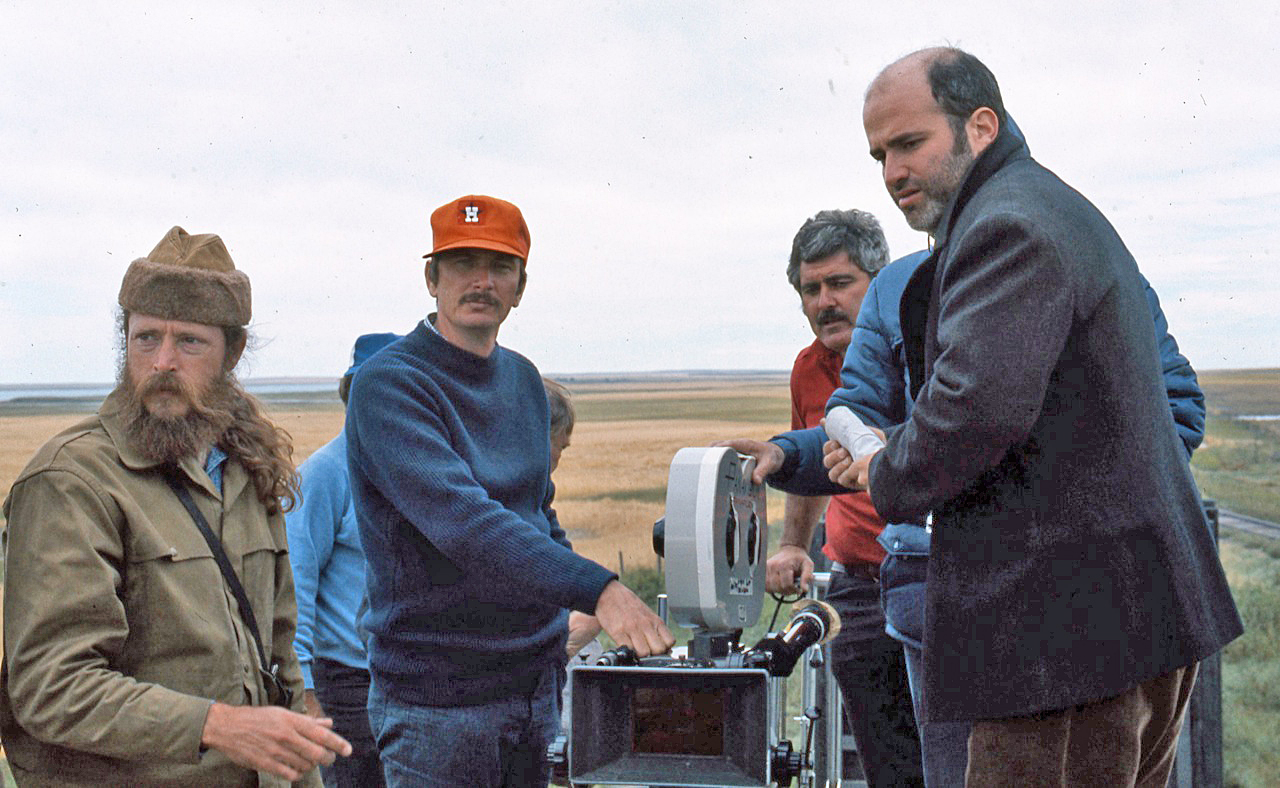

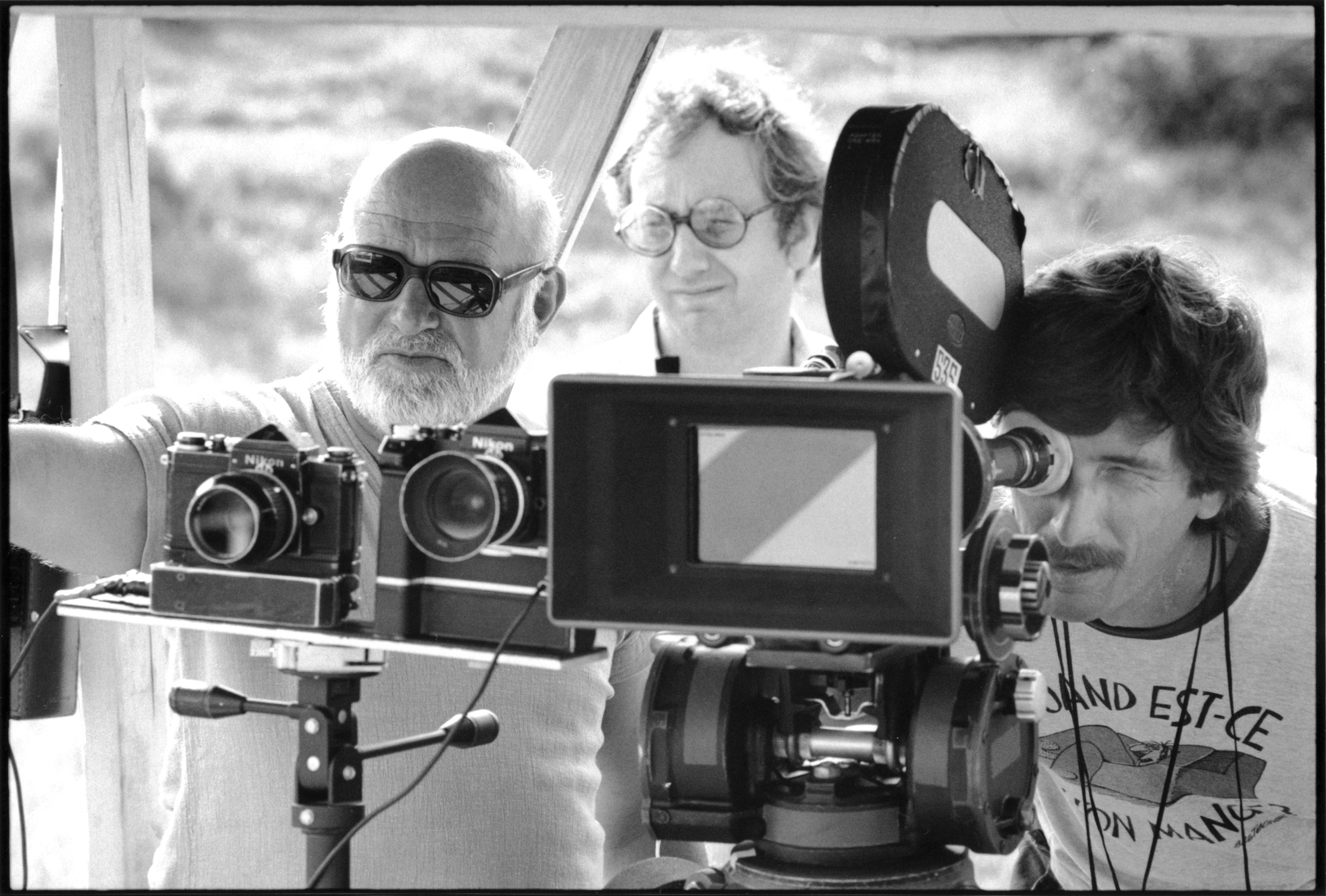

Upon leaving USC, Bailey found jobs in the camera department on several "zero-budget" films. “Working as a camera assistant, even at the loader stage, was physical work, and I found it to be immensely satisfying.” Then, on the cult favorite Two-Lane Blacktop, he worked as an assistant under Hungarian cinematographer Gregory Sandor, who taught him about the precision involved in classical cinematography. Another formative influence was director of photography Jimmy Dickson, whom Bailey credits as an essential supporter.

Later, as the operator on Robert Altman’s 3 Women, Bailey learned about setting an optimistic tone on the set from Charles Rosher Jr., ASC, and while operating for Néstor Almendros, ASC on Days of Heaven, he observed brilliant applications of single-source natural lighting. Bailey also served as operator on Winter Kills, and credits the anamorphic compositions of that film’s cinematographer, Vilmos Zsigmond, ASC, as inspiring his own abiding love for the wide-screen format.

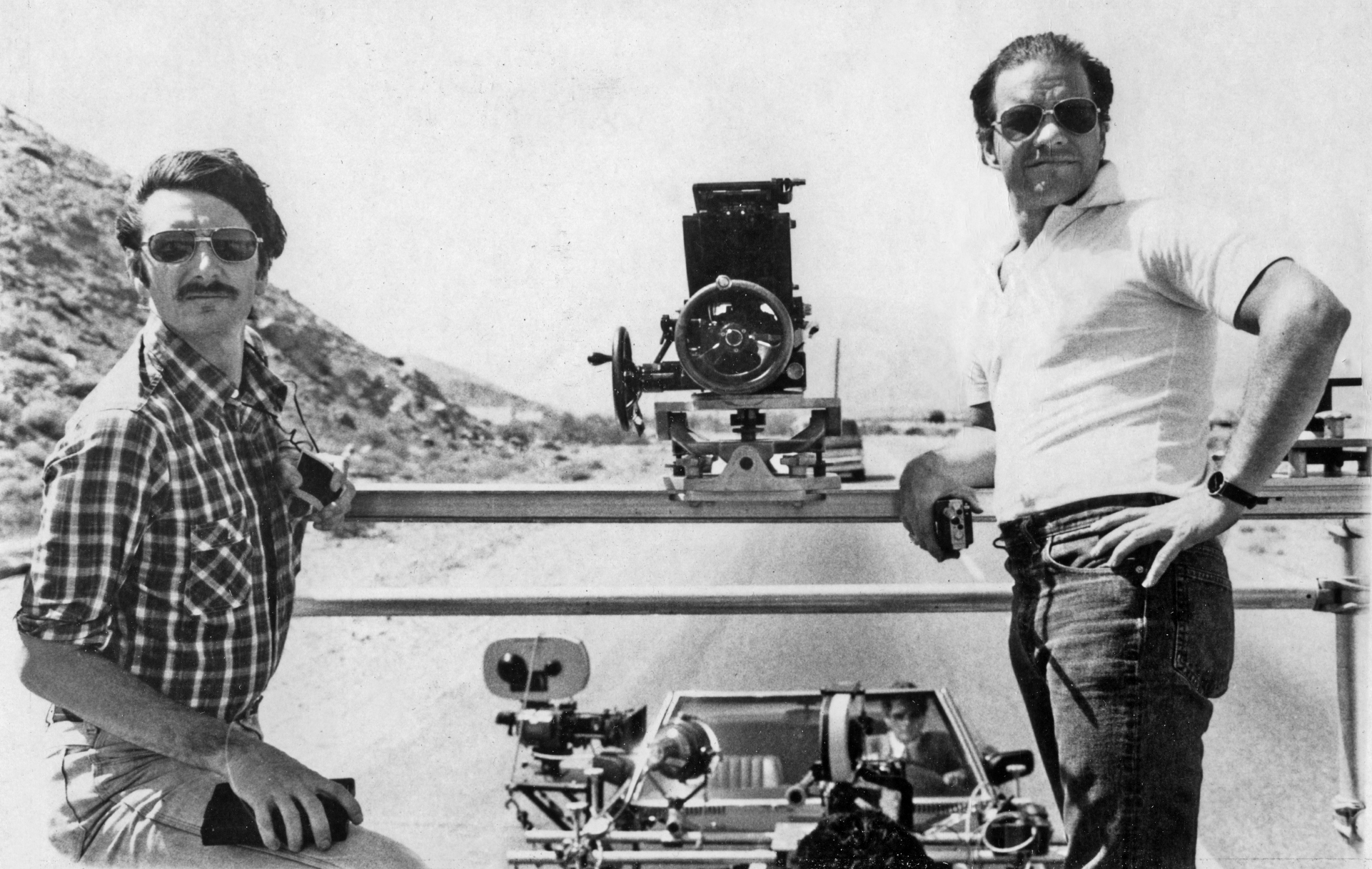

After Bailey shot some small features, agent JoAn Kincaid secured him a meeting with writer-director Paul Schrader, who was prepping the stylish, sexy drama American Gigolo for Paramount. A former film critic, Schrader went into the meeting intent on hiring a European, but, impressed with Bailey’s keen knowledge of foreign film — The Conformist, in particular — the director hired him instead.

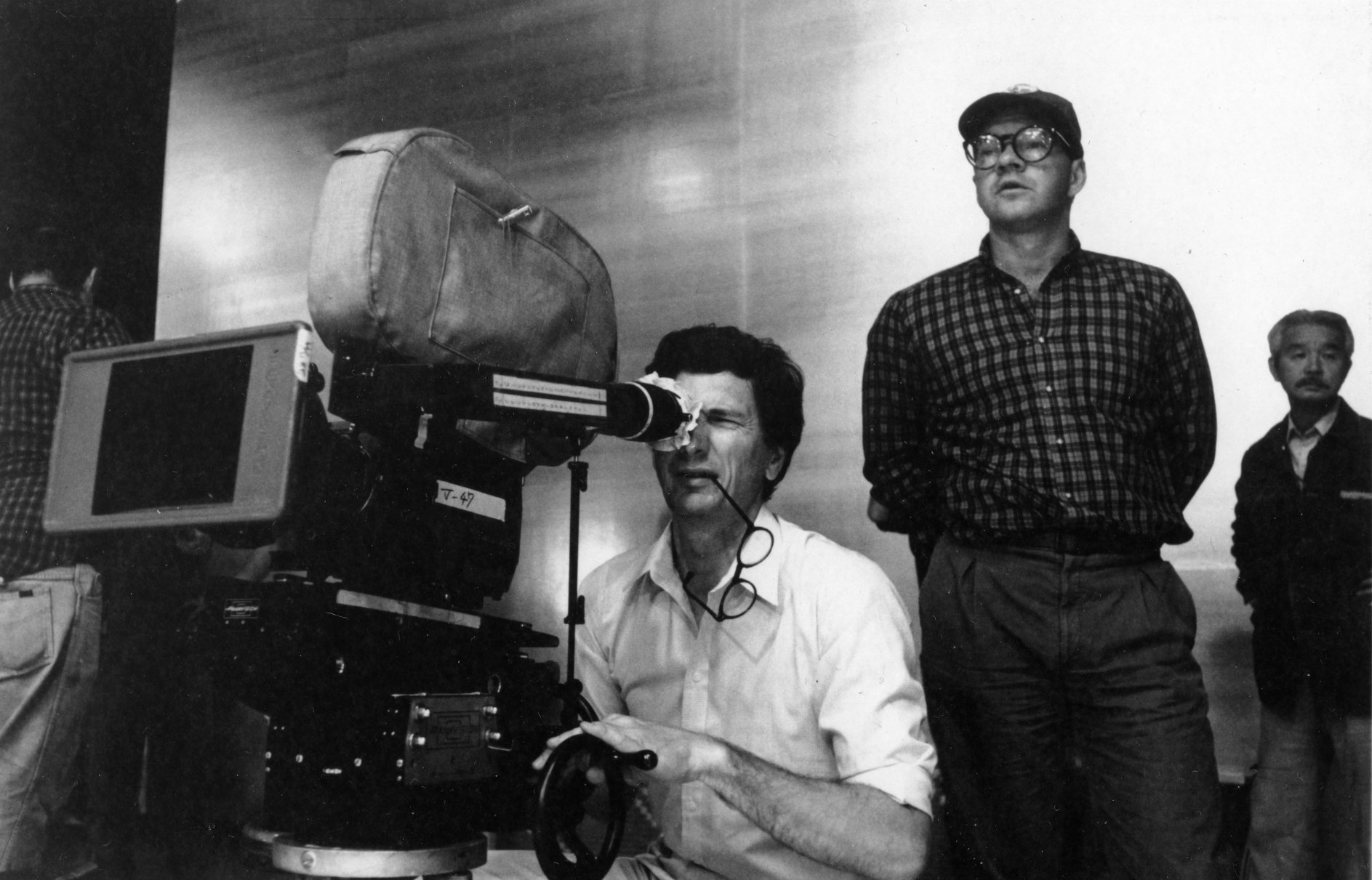

After the success of American Gigolo, Bailey and Schrader’s fruitful collaboration continued with the highly stylized Cat People, the lyrical Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters, and the emotionally raw Light of Day.

Bailey soon found himself meeting with Robert Redford to discuss his directorial debut, Ordinary People. The cinematographer admits that his understated camerawork in the picture does not have a look that declares itself — nor, he says, do most of his films. While he brought ideas about color and light from his love of painting, he made a decision early on that his cinematography would be only one component of a whole film and not an end in itself. Unless self-conscious stylization was called for, he wanted his work to be “invisible.”

Bailey’s working relationship with Lawrence Kasdan began with the naturalistic, character-driven drama The Big Chill and continued with the larger-than-life Western Silverado. But it was The Accidental Tourist that Kasdan refers to as “my favorite collaboration with John. It’s one of his best movies, and mine, too. John is so sensitive to nuance, and that movie is all nuance.”

Another of Bailey’s close allies has been director Ken Kwapis. "My collaboration with him has been the abiding continuity in my career," remarks Bailey. Their 30-year relationship has included six films — from 1988’s Vibes to A Walk in the Woods [2015].”

Bailey has also kept close tabs on technological developments. In 2000, when virtually every theatrical feature was still shot on film, he experimented with PAL video for The Anniversary Party. He then shot the mockumentary Incident at Loch Ness starring Werner Herzog in NTSC.

Bailey received the ASC Lifetime Achievement Award in 2015, noting at the time: “I’m happy that it reflects my whole body of work so far, and I’d like to believe it is also a recognition for work I’ve done for the organization, and my writing and teaching.” Not incidentally, he has been contributing to American Cinematographer since 2009 with his ongoing blog John’s Bailiwick, which chronicles not only his interest in filmmaking, but all manner of arts and artists.

Here, in an interview conducted at the ASC Clubhouse in Hollywood, just before Bailey traveled to Poland, the cinematographer discusses his career behind the camera, this new honor from Camerimage, his love for international cinema, his two-year tenure as president of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, and what it takes to succeed in a very difficult business.

American Cinematographer: What are your feelings about this Lifetime Achievement Award honor from Camerimage?

John Bailey, ASC: I’m very excited about it. I’ve had the great privilege to twice introduce and make the presentation to previous winners. I think back in the early years of the festival when it was originally held in Toruń, their first venue. It was the year that — 1994 I think — both Vittorio [Storaro, ASC, AIC] and Witold [Sobocinski, PSC] received the Lifetime Achievement Award. I gave the award to Vittorio. Then, several years ago, John Toll asked me to make a presentation to him for his Lifetime Award. Now the festival is back in Toruń, I’m very happy about that, because that’s where [my wife] Carol [Littleton] and I first went. We weren’t there the first year, but we were the second and, I think, third years and then, again, in the late 1990s, before the festival was relocated in Łódź. I never went to Łódź. I had a long gap from the late ‘90s into the aughts and the early teens, because I was shooting so much and the Academy presidency made it impossible for me to go because the Board of Governors and all the work there. I just couldn’t get away. But I’m free now. I have my life back. I went to the Academy office last week to pick up some things and someone said, “John, you look 10 years younger.” Gee, I wonder why that is!

“[Being honored] puts a period in context, and allows me to think about ‘What do I want to do next,’ whether it’s making movies, whether it’s expanding some of the things that have been of interest to me already.”

Tell us little bit about your experience of being the Academy president for two terms.

I had no idea how stressful that job was going to be. Part of it is my own fault because I decided to take on some issues that I thought really needed to be addressed, that — particularly regarding international membership and the fact that we had been sitting for decades on an old system where it was almost impossible for non-industry or non-Hollywood people to really get into the Academy because of the limitations of the sponsorship process. So, we changed that. In the last two years, 50 percent of new Academy members were international. One of the great pleasures I had, almost on the very last day I was sitting there, was signing something like over 800 new member certificates. I signed each one of them. One of the new members was Jean-Louis Trintignant. I mean, he’s 88 now, and one of the great iconic figures of French cinema of the ‘60s, which, as you know, is a period that was very important to me. So, I signed new member certificates for him, for Giancarlo Giannini, a major Italian actor kind of parallel with Marcello Mastroianni. Also, Lady Gaga, which was of more interest to most people because they may not know who Trintignant is. So that was great. There were things like that that I really felt good about, as well as being able to support the Margaret Herrick Library and the Academy Film Archive. Also, the screening program I started, “Films on Film,” showing 35mm prints — things like that were very important to me. As I’ve said to many people, Hollywood, the Oscars and the studios will take care of themselves. We got in way deep regarding the [2019] Oscars ceremony. The no-hosting, the host, no-host, the so-called, misnamed “popular Oscar,” the lynching from my own brothers and sisters regarding the proposed cut-down versions [of on-stage award acceptance] for the show, which had passed unanimously by the Executive Board of the Cinematographers Branch but then got misinterpreted. Some very esteemed cinematographers reacted very badly, very aggressively and nastily, I must say, and it was personally deeply painful at the time — but that’s all past, and the Camerimage tribute was very healing. And now I can go back to my former life, shoot a few more movies. We’ll see.

Now that you’ve completed your tenure at the Academy, what’s the next career phase for John Bailey? You’re at an interesting point where you’re being honored for a lifetime of work, so, you have the opportunity to really look back in retrospect. You’ve done this before, when you got the ASC Lifetime Achievement Award in 2015, but I have to imagine there’s an even deeper sense of self-reflection when it happens again.

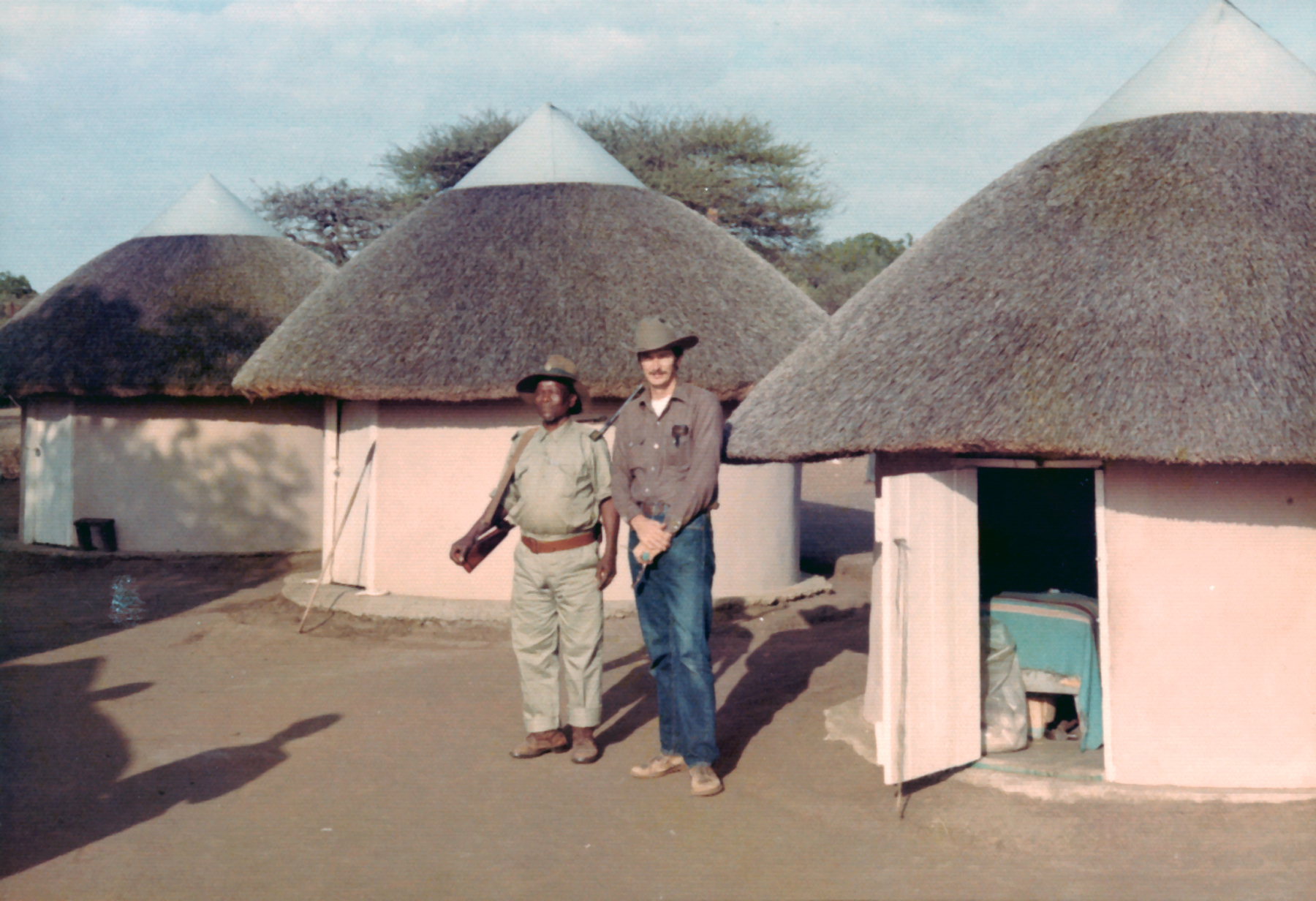

As you know, even though I’ve spent my life — myself and Carol, both of us — working inside the Hollywood system, our real love has been international cinema, documentaries, independents and experimental films. This award from Camerimage is really an international award. It’s of a different dimension in a way — which is not to minimize the ASC’s award, as I was very deeply honored by that — but this is something else. As you know, the festival publishes a book for each honoree, documenting their career, and working with [festival founder] Marek Żydowicz and the editor, Marek Zebrowski, on this has given me an opportunity to look back — a retrospective look at over 50 years of work from the time I was a camera assistant. There are more than 40 movies reflected with little chapters, photographs and comments, plus some personal things from my childhood. I hope it’s something that will end up in libraries and people will keep. It’s been very important for me, working with Marek, to essentially look at a synthesis of this work and look at connective tissue between films. You discover that there are certain things that represent a continuity in terms of what you are attracted to. For me, it has always been family dramas. And, to a certain extent, romantic comedies because they’re not violent. They’re not abusive. They’re fun, usually. But family dramas have been always very important to me. So, putting this book together, it has been possible to look back at how these different family relationship films have refracted against each other. For me, it has been a learning experience as well as a nostalgic one. As you said, it puts a period in context, and allows me to think about “What do I want to do next,” whether it’s making movies, whether it’s expanding some of the things that have been of interest to me already. And, obviously, the blog I do for American Cinematographer. So, we’ll see.

“I really didn’t have a circle in terms of peer group. I was an outsider. I had no family in the business.”

Given your writing, I’ve always been surprised you haven’t written a book yet.

When you see the Camerimage [commemorative honoree] book, there’s always a text introduction. It’s usually based on a few writings the cinematographers have done. But, basically, put together from Marek Zebrowski’s interviews. For this book, I wrote everything. I pulled things together — from reworking some blog pieces or even before the blog pieces I had written for the magazine in the 1990s. A lot of it is reflections on cinematographers that have been important to me, and not just people like Vittorio or Néstor [Almendros, ASC], but a man almost nobody knows, Gregory Sandor, who I worked with at the very beginning of my career as an assistant and was the de facto cinematographer on Two-Lane Blacktop, which was a very, very important film for me. So, much of what I learned about cinematography and how to have set decorum came from Gregory, who was of mixed Hungarian and Cuban. I don’t think he ever even got into the IA [cinematographer’s guild]. He never really broke the mainstream. He photographed two early films of [director] Monty Hellman before Two-Lane Blacktop. He did two back-to-back low-budget westerns with Jack Nicholson. I think they were done either for AIP or Roger Corman, Ride in the Whirlwindand The Shooting, which are cult-classic films. Then Greg went on to do Two-Lane Blacktop. So, I talk about that. I talk about art to a certain extent. There is a lot of text, about 75 pages. I don’t know who’s going to read it. Maybe somebody will. I hope it’s really readable because it’s not just about me and it’s certainly not just about the craft and art of cinematography. It’s about the relationships and the humanity and working with people, which, as you get older, becomes more and more important. You realize that the life you’re living is not just the art of the movies you’re shooting but the relationships, the humanity that you have with people. When we’re young and ambitious and deeply focused on our career and making our mark, our identity in terms of who we are as artists, that is really very much to the fore. As you get older and you reach a point where you feel “Well, I’m there as far as I’m going to be or as whatever — there’s not much more I can prove or do,” you start to change your perspective and you start to look at the humanity in your relationships. I’m getting ready to do a blog post on Robert Frank. I didn’t think I’d do one because everybody has written about Robert Frank in the past few days. But I found a link to a program he did for the BBC in 2004 — a crew followed him around in New York and a little bit at Mabou, Nova Scotia. Robert had a summer place there with June Leaf. You really see the humanity of the man. He’s not — he doesn’t talk at all about his photography. He talks about relationships of people he knew that were important in his life who continue to be important in his life. I think, for me, this book that Camerimage is doing is really about the people that I have had the good luck to work with for the last 50 some odd years. That’s what I’m really happy about.

“I did not want to do tawdry films. I did not want to do exploitive films or violent ones. I really held out, sometimes at great personal expense, literally, in terms of money, to do films that I knew were building a résumé that when I did become a director of photography that that was part of who I was.”

After going through this retrospective process, what do you think of that young John Bailey who was a camera assistant and very focused and ambitious? Who was that person? Reflecting back, what do you think of that person today?

I think he was pretty insensitive to people. He had a fairly narrow focus on moving forward in the world and forging a place for himself. He was obviously an acolyte of some very gifted people and felt — what can I say — not ‘intimidated,’ but certainly felt privileged to be able to work with some of these people. But he also wanted to assert himself. I think I say that because I don’t think I was much different than a lot of younger people starting off. It’s just inherent in who we are at a certain point in our life. We have this need to not only find our identity for ourselves but to let other people know who we are and why we are different from somebody else. It’s not even a question of feeling that you’re better or more artistic or anything than somebody else. It’s just that you are a unique person. You know? I think that for a good part of my career, certainly as I was on the way up as a camera assistant and as a camera operator in my early years as a director of photography, I was fairly consumed by that and not always as sympathetic to some of the crew that I worked with. I mean, I was not a screamer. I didn’t insult people. I never — you know, these things you hear about temper tantrums and throwing stuff around. I was never like that. But I was so narrowly focused sometimes that I was really not engaged with the human and personal dimensions of some of the people I worked with. In the last 15 years, especially in the last decade, that has become very important to me.

Early in a career, the pressure on you would have been immense. Because every project could potentially be a pivotal moment.

Pivotal up or down. And it’s the ‘down’ that creates the real pressure, because we know that in the film business, as you only get so many chances. And if you’re dealt the wrong cards or you deal yourself the wrong cards, you can be finished. I saw people, young cinematographers from the time I was an assistant and an operator who essentially had their moment. They either blew it themselves or things happened that were out of their control. The stars didn’t align for them and they went down. Some of them disappeared completely. Some of them just had less successful careers than they might have wanted. I always felt that I got incredibly lucky. You know? But I did have a singular focus on the kinds of films I wanted to make, even from the time I was an assistant and as an operator. I did not want to do tawdry films. I did not want to do exploitive films or violent ones. I really held out, sometimes at great personal expense, literally, in terms of money, to do films that I knew were building a résumé that when I did become a director of photography that that was part of who I was. People could look back and say, “Well, yeah, he was an assistant,” or, “he was a camera operator, but he worked with Monty Hellman. He worked with Robert Benton. He worked with Terry Malick and Robert Altman.” That made a big difference when I decided to become a cinematographer. I’m not sure that a lot of young cinematographers understand that. Of course, what we know as the apprentice/journeyman system of going up through the ranks still exists, but it is not obligatory anymore.

“Despite the myth and my dear French filmmaker colleagues who created the ‘auteur theory’ — coming out of criticism in the late 1950s and early ’60s which said that the director is the source of all genius — that is just not the way movies are made.”

Actually, you’re of the generation where that process actually stopped being obligatory.

Yeah, well, it was still somewhat obligatory for my generation. Look at my peer group, people like [ASC members] Steve Burum, Steven Poster, Jim Glennon, Allen Daviau and John Toll. Name a whole lot of them. We went up through the ranks. I mean, not Allen so much, but we others did. John and I were assistants together.

Just to clarify, before your generation, there really weren’t film schools the way that there are today. And going to a formal school became a parallel pathway to build a career.

Right. USC was the preeminent school in the 1950s, ’60s for people that wanted to be craft-oriented. We certainly knew about Ted McCord and Connie Hall, but we also knew that — this was before any embrace by the industry of film schools or even — one of the first things I remember was when Nissan — I think it was still called Datsun at the time — when Nissan gave awards to film students at a festival. That was an early thing that went back, I think, to the ’70s. That was one of the few — beginning of the openings of industry embracing the film schools in a very public way. Of course, now a lot of people look at, especially the West Coast film schools, as farm teams for the studios. Not without reason to say that. But Caleb [Deschanel, ASC] and I were at USC together at the same time, in the mid to late ‘60s, we were cautioned, “Whatever you do when you go out on a meeting for a job, do not let anybody know that you went to film school.” It was a kiss of death. Even when I got in the ASC in — what was it — ’85 or so, I used to tread lightly about my film school education, especially around people like [former ASC president] Stanley Cortez. [Laughs]

I also went to a film school, San Francisco State, which has a very artist-oriented program.

Oh, very much so, yeah.

Especially back in the mid to late 1980s when I was there. But one of our visiting filmmakers who left a strong impression on my class was your longtime collaborator Paul Schrader.

Oh, yeah?

He came in and also talked about relationships. That left a big impression. Let me just — it’s not too long a story.

No, please, please. Go ahead.

Schrader came in and addressed the class, talking about how he built his career, telling anecdotes and stories regarding other filmmakers he had worked with. He would say things like, “Well, my friend Marty,” Scorsese, of course. The stories piled up and revealed a pattern of relationships and collaborations between filmmakers of a certain age, helping build each other’s careers. That was the thing that I took away from it, that you have to find a peer group that you fit within and basically help each other build careers.

Well, Peter Biskind’s [1998] book, Easy Riders, Raging Bulls deals with some of that, doesn’t it?

Exactly. Then, someone in my class raised their hand and said, “Mr. Schrader, it sounds like if I’m not already in one of those circles, there’s no chance of me ever getting into them.” He laughed and he said, “No, there isn’t. You have to make your own circle.” How did you go about making your own circle and who were the key people that helped — your key collaborators that help you build a career?

I really didn’t have a circle in terms of peer group. I was an outsider. I had no family in the business. When I started as an assistant, even up through a good part of my time as an operator, benign nepotism was still very, very common. It was very hard to break in, which is why I worked with people who were not necessarily A-list cinematographers. And there were also issues with the union, regarding the roster and seniority, but also nepotism. Very early in my career, not that long after I got into the union, I contacted Robert Surtees [ASC], who was getting ready to do a film with [director] Herbert Ross called The Turning Point. It was about the world of ballet, which I loved. I was — I felt I could bring something to it. So I wrote Surtees a letter and tried to set up a meeting. I explained to him a new camera support that was just now starting to be used — the Steadicam — and how interesting it would be to use it inside the proscenium, almost as part of the choreography. And he wrote me back — I still wish I had it — a very short but very nice letter, saying, “Thank you for your notes. Very interesting. My assistant does all the hiring.” That was it. That was the closest I ever came to making a contact with a what you would call a real A-list studio cinematographer. The closest I got in terms of Hollywood was working as camera operator for Chuck Rosher [ASC], who was Charles Rosher [ASC]’s son. But they did not have a good relationship. Charles was Hollywood royalty. It’s the closest I ever came. Then most my other relationships were with international cinematographers, with Néstor, for example and Vilmos [Zsigmond, ASC, HSC], even though Vilmos, by then, had become totally involved in the Hollywood system. But Vilmos really never was fully integrated. He was often called —“the Hungarian.” Lazlo became more American, more integrated. But I remember one of the last times I saw Vilmos — I was doing a video interview with him for the Criterion Collection, for an extra on their Blu-ray release of his film The Rose. We looked at a couple sequences and as we talked about them, I realized, “Here’s a man who is still thinking like a European artist, even at the end of his career.” I really respected that. But it also made me realize how much of my own perspective on cinematography, on cinema, was still very much imbued with an international perspective. That’s true to this day, for good or bad.

“If you think getting out of film school with a thesis film — even 40 years ago, but less so today, but still true — is going to launch your career… It has happened, but it’s very rare.”

When you go to festivals like Camerimage you’re met with young, aspiring filmmakers, especially cinematographers, I’m sure you’re asked a million times, “How do you make it in this business?” Looking back at your career, is there any correlation between how to make it in the business then versus now? Is it completely different, or is it exactly the same?

That’s a really good question. I don’t know what the answer is because I think to really be able to answer that, I’d have to be in the flow of people that are trying to make it now. It’s hard for my outsider perspective to really know what it’s like other than that nebulous question that is timeless, “How do I get an agent and how do I get started in the business?” The only thing I’ve ever been able to say is prepare yourself for the long haul. If you think getting out of film school with a thesis film — even 40 years ago, but less so today, but still true — is going to launch your career… It has happened, but it’s very rare. You have to understand that you need to make the commitment, as Vilmos has said, and, essentially, as Werner Herzog has said… In a lot of ways, they were very similar in their sense of rigid aesthetic discipline in terms of their work. In short, if you’re not willing to make the commitment for 10 years or 12 years, whatever it is, assuming that something could break for you earlier at any given moment, you should probably do something else with your life, because it’s just not easy. I’m not just saying that because that’s how long it took me. I got into the union in May of 1969 and I shot my first studio picture as a director of photography in 1978 — basically, 10 years. But I had been working as a camera assistant for three years before I got in the union, too.

As my father frequently reminded me, “Every overnight success is 10 years in the making.”

It really is that simple. I think probably one of the most difficult things to make young people understand in an age of social media, instant gratification, short attention spans and irresponsible aphorisms like “Just Do It,” is that somehow, if we don’t succeed fairly instantly, that there’s something terribly wrong with us. The one thing that I learned more than any other in those 10 or 12 years I spent as a camera assistant and as a camera operator was understanding becoming successful as a cinematographer isn’t about learning the equipment. It’s about learning how people work together, forging relationships, dealing with the stresses and the sort of unexpected accidents and gifts that you’re given day to day, and developing a perspective that when you go to work in the morning you’re not executing a blueprint based on storyboards or discussions or anything. You are in a living, changing, spontaneous, human flux. Anything can happen at any given moment. If you are not prepared to be open to that and embrace it, or if you don’t want to embrace it because you don’t like it, at least understand it and have some positive attitude. Otherwise, you are in the wrong business. Despite the myth and my dear French filmmaker colleagues who created the “auteur theory” — coming out of criticism in the late 1950s and early ’60s — which said that the director is the source of all genius, that is just not the way movies are made. Certainly not in the American system, and I would think most people would acknowledge not really anywhere. I mean, you do have a few filmmakers like Ingmar Bergman, Andrei Tarkovsky, Lech Majewski and Béla Tarr, but that’s not the way most movies are made. If you’re not prepared to essentially embrace the chaos and embrace the indeterminacy of every day in your work, then you really should not be a cinematographer. Being an editor, at least, you get the footage and you can work it and you can try different things. Cinematographers are more exposed than anybody else, in a funny way, even more than directors, because they are often covered by the actors. As a cinematographer, you are there with that machine and your crew and they’re all looking to you. You’re responsible for them. You’re ultimately responsible for getting the day’s work done. I mean, you work with the AD and certainly the director, but we all know, also, there are plenty of directors, young, middle-aged, and old, who essentially have blind spots regarding the responsibility of getting the day’s work done. But the cinematographer can’t use that, or anything else, as an excuse.

“I’ve always found that you absolutely must have a good, trusting, open relationship with your crew — and not just your camera crew, but your grips and electricians as well. I mean, I’ve had dolly grips that have given me great ideas about shots and how to improve shots.”

The cinematographer is tasked with taking something that’s on the script page and become this shared mental vision, then actually executing it in a way that it can be photographed in a real world.

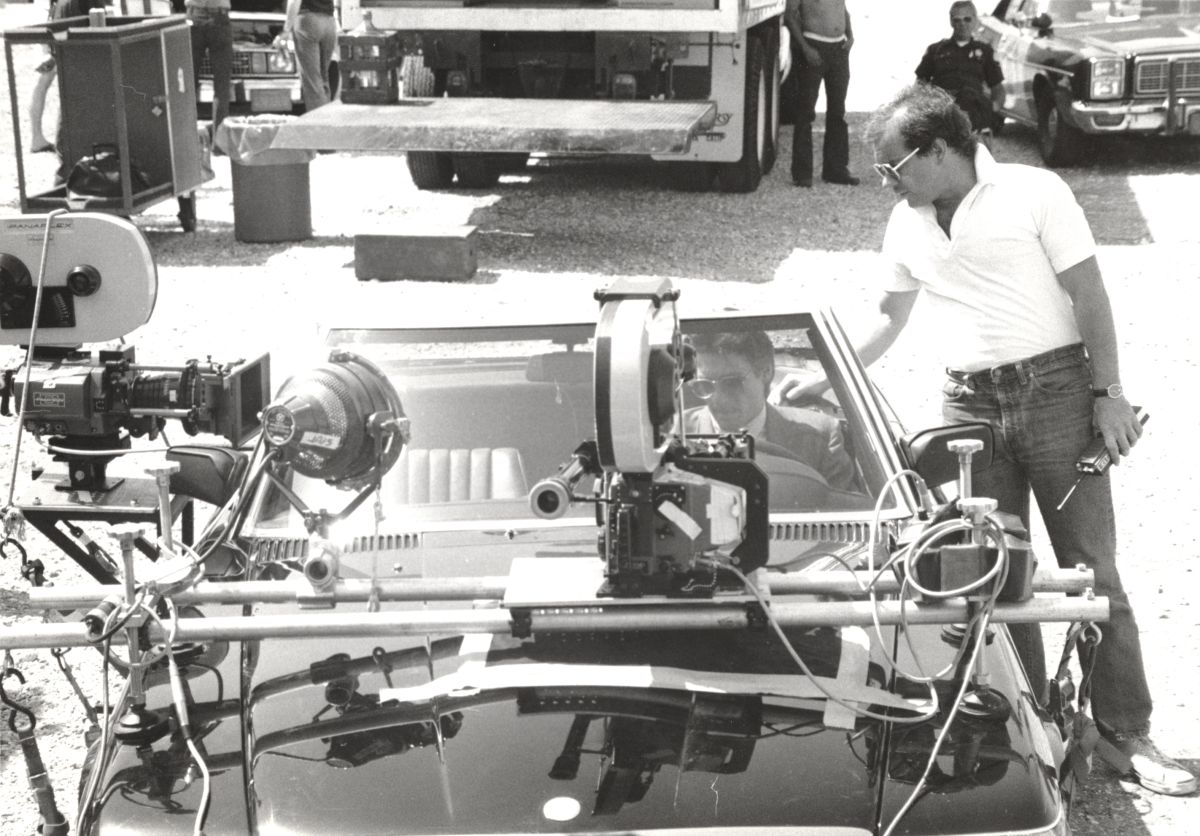

Yeah. You were mentioning Paul Schrader earlier. I did five films with him [American Gigolo, Cat People, Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters, Light of Day and Forever Mine]. I’d read his scripts and they were almost like Harold Pinter, at times. They’re dialogue. They set the scene. They give the minimum of details of what you need. But he often does not call shots. He does not essentially tell you how people think or even how they’re moving unless he has to. His scripts are very reductive. That’s very interesting because he is a writer and he is an auteur. Marty works very differently. He storyboards often. Paul hardly ever storyboarded anything. We would do a few sequences, but that notion of having this ability to create spontaneously — I mean, Paul and I, we would sometimes each have a viewfinder and we’d be looking at each other 180 degrees, just waving at each other. But, ultimately, Paul and I had a great ability to survey the scene and find a synthesis, and it was a really good working relationship. You know? That’s what it needs to be. It needs to be collaborative. I’ve always found that you absolutely must have a good, trusting, open relationship with your crew — and not just your camera crew, but your grips and electricians as well. I mean, I’ve had dolly grips that have given me great ideas about shots and how to improve shots. And if your crew knows that if they have an insight or an idea, that they can come to you and share it, that’s really great. That’s how movies are really made.

When I was a film student, it was completely drilled into our heads that we must have storyboards, shot lists, lighting and camera plots, et cetera. Then I read a great book about Sam Peckinpah — If They Move…Kill ‘Em!” — in which he talks about how he never created a shot list until he got to where they were going to shoot with the actors and they blocked the scene. Only then would create a shot list. Otherwise, if you don’t know what the actors are going to do, how can you set shots? Because he never wanted to control his actors to that degree. It’s almost an anti-Hitchcockian approach.

Exactly.

Can you describe your process of working on location and how that process impacts how you prepare and your work?

Again, we were talking about this notion of flexibility and spontaneity. In preproduction, you start to read all the cards in a deck. The kings being, of course, the director, essentially — or the aces. You have to understand and be able to read those cards. A key part of that is scouting locations, deciding the appropriateness of the locations for the way you think a scene may play. Will it be liberating for what you want to do rhythmically, visually, and dramatically with the actors? Understanding how locations can determine the choreography of the actors and how they move — which can dictate camera and lighting — is very important to the cinematographer. [Film] actors, for the most part, are very physical in how they deal with things; their ability to create character and performance is alive and a response to their surroundings, as opposed to [stage] actors on a proscenium stage. So their action is based on the way you use those spaces, which makes location scouting very important. I remember when I was scouting locations with John Schlesinger for Honky Tonk Freeway — we would walk into a room, a possible location, and Nando Scarfiotti, the very smart, sophisticated production designer who did so many Bertolucci films, and who I did American Gigolo and Cat People with, would pick these beautiful spaces that were architectural, that were aesthetic. Then John would walk in, look at them and walk around the room a couple of times. Sometimes he’d say, “No, it doesn’t work.” It would be a great location. I started to try to understand because that was still early in my career as a cinematographer, wondering “What is he thinking?” It’s not that he was planning in his own mind the actual shots or the choreography, and he certainly had not made any storyboards, but he knew the scene. He knew the dialogue. He knew what he thought the actors would need physically, architecturally in that scene and whether that space could serve it. I remember I asked him about that one time after he had rejected a location. He said, “Well, John, it’s really about the actors and what the actors need.” He also said, “If I have cast the movie properly with the right combination of characters and relationships, my work is 80 percent done.” Now he was being very modest at that, but I understood what he was talking about. I’ve always kept that in mind. Robert Redford was the same way. The film I did right before Honky Tonk Freeway was Ordinary People. Redford was so attuned to the physicality of space for the actors that he — being an actor himself, and this was his first film as a director — he would get out there and move in the space, reading from the script. Not that he was mechanically trying to tell the actors where to go or how to turn their head, but he understood actors have to inhabit the space. If the space is limiting or the — what can I say — the aesthetic or compositional values impinge on the actors in a way that compromises their dramatic space, then it’s not right. On the other hand, of course, if you’re doing a film that deals with compromised and constricted characterizations, that control of the physical space is essential because it defines them in terms of the narrow parameters of their own life. Of course, I think of most of [Bernardo] Bertolucci’s films, but particularly The Conformist. I mean, Jean-Louis Trintagnant, all of those characters, they are all very strongly defined by the light and the physical space they’re in. You look at that film and it’s got a great deal of emotion, but it is an intellectual emotion, intellectual slice of aesthetic emotion. I mean it’s a very cold film, ultimately, as are most of Bertolucci’s films. So, I realize that as much as I love — and Carol loves — international films, especially French films, our sense of cinema is very much American and it’s based on character and dialogue. I love Béla Tarr and there’s almost no dialogue in his films. If you look at a film like The Turin Horse, there’s virtually no dialogue except for one eight-minute scene, which is a monologue in the middle of the picture. A lot of European films that I like, they’re very reductive in the dialogue. American films, for the most part, aren’t. The films I have photographed, for the most part, are very strongly dialogue-based. I realized when I was doing this book for Camerimage and looking at the films that we selected to have photographs and comments on, how many of them were derived from literary sources, either from novels or theatrical stage plays. That’s a mixed bag, you know.

“A good part of my career as a cinematographer has been me trying to deal with my basic introversion. But I always understood that as a limiting factor. So, I always felt that having camera operators that essentially were out there and could engage the actors was a real asset.”

What’s your perception of the working relationship between cinematographers and the cast? What are key things that every cinematographer needs to know about, the acting process, and how that’s going to affect the cinematography? Do you think good actors have a strong perception of how cinematography is going to affect their performance?

A lot of actors are intimidated by the camera, even very experienced ones. They’re looking for any assurance that they’re not going to look foolish or, in the case of women, of course, that you’re not going to make them look bad. So, a lot of them have very defensive positions that comes across, sometimes to cinematographers, as though the actors are the enemy or they’re antithetical to cinematographers. In fact, it’s just a misunderstanding. I think most actors I’ve worked with are actually very interested in cinematography. I mean, I could name a whole list of them. People like Richard Gere, who is a photographer in his own right, a still photographer. A number of actors that I’ve worked with are photographers, and some of them have made their own movies. One of the things that makes an actor feel comfortable with regard to the cinematographer in relationship with the camera crew is an ability to explain when you need something; explain what it is you need for them to do. If you’ve got, for instance, a very specific lighting cue, engage them. Let them know what it is and why and solicit their opinion. If they don’t want to do it, ultimately, you have to abandon it. But it’s all in the presentation. A lot of cinematographers really do not want to be involved with the actors. So, there’s a — it’s not a hostility; there’s just a state of non-communication. That is really not productive for the actors or certainly for the cinematographers in terms of getting a real dialogue and understanding going. The lynchpin, a lot of times, is the camera operator. I’ve always tried to work with camera operators who I felt had outgoing personalities, that had an ability to talk directly and with respect but also with a familiarity to the actors. I’m not the most expansive person in the world. I think, as I’ve gotten older, I’ve gotten a little more extroverted, but I’m basically a very introverted person. A good part of my career as a cinematographer has been me trying to deal with my basic introversion. But I always understood that as a limiting factor. So, I always felt that having camera operators that essentially were out there and could engage the actors was a real asset.

As your surrogate?

Yes, as my surrogate. I think of people like Lou Barlia, who was a real New Yorker, from — I think he was from the Bronx. And Ben Speck, who I’ve worked with a number of years off and on. Just a number of really wonderful operators like Matt Moriarty, who was my intern on As Good as it Gets. But an operator that, essentially, is judgmental toward the actors or looks at actors missing a mark or something like that as screwing up the shot and throwing your arms up like that, it’s — well, they can bury you. Quickly.

Going back to your preparations on this book for Camerimage, are there things included in it that you thought, “I don’t know if I want to put this in; this is too personal,” or, “I wonder what people will think of this”?

I did think about that a little bit, but dismissed it almost immediately. I look at this as a testimonial, as like — I feel like this book is going to expose me on a personal level more than anything I’ve ever done. I talked to Carol about it a lot. We both thought, “Well, there is something satisfying about this,” for me, to just let go. I also think being honest and candid can be informative to people, especially to younger people who may want to read it. They can see that there is a vulnerable human position, person, behind this. We think of — I think of some of the gods of cinematography and you think of them as these icons. In fact, they were very vulnerable men and women. I knew some of them, especially people like Néstor. There are some who hide behind the image. I decided not to do that. I mean, I hope this book is more revealing than I even thought that it was going to be. I do talk a lot about myself, but it’s usually in relationship to the people who I’m working with. In fact, I tell a lot of stories on myself. I feel I’ve got moments in there where I expose my own naivety, my own limited ability to engage with people. I have several excerpts from a journal that I wrote when we were doing A Walk in the Woods. I’d always wanted to do a journal but I never seemed to have had time, which means I guess I didn’t think it was that important.

When we were in prep for A Walk in the Woods, I started to think back, “You know, at the beginning of my career, I worked with Redford, and here I am almost 35 years later doing another film with him.” We were both in very different places in our life. We were able to talk and engage. I thought, “It would be good to use this picture as the basis for a journal about the making of a film.” I’m not talking about the camera and the lights, but about the crew and the locations, and some of the crazy things that happen when you’re making a movie. I mean, we shot it in and around Atlanta, for the most part. That, of course, is Waffle House kingdom. We used to have a lot of fun with Waffle Houses and the whole joke of what they represented and everything. One day, there was a holdup at one of the Waffle Houses on the outskirts of Atlanta. A guy held up a Waffle House with a pitchfork. It actually turned into a chase later on and somebody ended up getting murdered as a result. It started off as a joke. But I started putting in this journal all kinds of anecdotes about things that were happening to crew members and to the world outside and the locations and walking into some of these locations and into people’s lives and saying, “We want to shoot in your house. We want to shoot in your store.” Looking at it as what it was, that you’re literally walking into somebody’s own history. I tried to put some of that in this journal. Anyway, so there are excerpts from this journal in the text of the book. I’m very proud of that. I don’t know how people will read that, but I hope it’s funny.

Recently, I’ve been doing a lot of historical research on cinematographers, and it’s quite shocking how little we know about many of them, even ones who had fantastic careers. And even if there is good documentation on their films, there’s an almost complete lack of information about their personalities. If you didn’t know them personally, there’s no way of finding out what they were really like. So it sounds like your book is going to be an invaluable resource for the future.

Yes, well, because of the interests I have in terms of film history and cinematography, I realize, as you said, how difficult it is to get inside many of these people. I’ve read a few of these memoirs by cinematographers and some of them are not very revealing. For example, Splinters from Hollywood Tripods by Virgil Miller. And Billy Bitzer’s autobiography [Billy Bitzer: His Story - The Autobiography of D.W. Griffith's Master Cameraman]. They’re not very revealing at all. The autobiographies tend to be more about the work. This is very much a part of most of the history of cinematography, where cinematographers, by their own definition and their own imperatives, have often looked at themselves as workmen, as technicians, or sometimes even as artists, but thinking that nobody would care or be interested. It was really about the work, the work, the work, the work, the work. Of course, the studios and the publicists and all the different ways that you could have found out who they were, they were all marginalized. So, there’s really very little information unless they actually did write something fairly revealing. There have been a few good biographies, though, like the one about James Wong Howe [ASC] that talks about the racial prejudice he faced…

Todd Rainsberger’s book?

Yes, that talks about when Howe first got a job at Paramount sweeping the floor at the sound stages. You look at the human dimension of all of these. The fact that Howe, who we look at one of these icons, but he had to hide his marriage to a Caucasian woman because of the anti-miscegenation laws in California until the late ‘40s. There are just a huge number of personal stories. I’ve always wanted to know more about the personal history of Gregg Toland, for example. He really does seem to be enigmatic. You can find little bits and pieces about — but as far as I know, there’s no real biography on Toland. I discovered that there is a wealth of material and there are — in the libraries and in the archives and there are scholars that are starting to do them. Christopher Beach has written a couple of books on cinematography now? [Including A Hidden History of Film Style.] There are, I think, realizations on the part of scholars that this is a very unmined field, biographies and profiles of cinematographers, a lot of whom had very interesting, exotic lives, a lot of whom married movie stars. For instance, Merle Oberon married Peckinpah’s cameraman, Lucien Ballard [ASC], who was from the same hometown in Oklahoma as my wife.

And, of course, Harold Rosson [ASC] was married briefly to Jean Harlow.

I’d love to know more about Rosson. He’s an amazing figure in terms of the range of the work he did from the glitzy Hollywood musicals for MGM, one of MGM’s real go-to people, almost to the extent that Leon Shamroy [ASC] was over at Fox. Rosson was at MGM but — you know, you say Harold Rosson on one hand and Leon Shamroy on the other, and a lot of people might not really know who Harold Rosson was. Yet, toward the end of his career, he did some exceptional black-and-white work on some noir-esque films. Obviously, there’s John Alton. There’s so many. Like Karl Struss, whom I actually met. Early in my blog writings, I did four posts on Struss, starting with his days in New York as a still photographer. I did a series of blogs on Jack Cardiff. You know, he wrote a wonderful book, Magic Hour. But it’s really not that revealing, just like Néstor’s book, Man with a Camera. Anyway, what I’ve started to do in this Camerimage book is begin to lay the groundwork for another book that I want to write. What I realize is the book will not be about cinematography in terms of, “And then I did this and this is what…” No, it’s going to be about the human journey. It became very clear to me that this would be the focus because the two years I had — well, not just those two years, but of my long-term involvement with the Academy and especially being inside the bubble the way I was for two years at a very tumultuous time. Matter of fact, I have a tentative working title for it. It’s called — wait a second... Deep Focus: From the Dark Room to the Board Room.

Can you believe that you went from the young aspiring cinematographer with no connections to becoming president of the Academy? It would be an immense journey for anybody.

No, it’s very hard for me to understand that. Carol and I both, because she’s had a parallel career. She was president of the local for six or eight years, the Editor’s Guild. She is still an Academy governor. She’s now one of the vice presidents in ACE. We sit around sometimes, having a glass of wine at dinner or something, and we look at each other and say, “Can you believe the journey that we’ve had?” She was raised on a farm in Oklahoma, in a small town. She had no connections. I had absolutely no connections. My father was a machinist. He never went to high school. No, there’s no way we could have ever foreseen what actually happened. At the same time, we realize that we were privileged in that we were born white and we were born at a time, even though we both came from working-class environments, that there was an opportunity in those decades in the 1950s and ‘60s when working-class kids could break free and enter whatever. And a lot of those doors have closed now. It’s very different. We have very much a de-facto class system today. It’s not so easy despite all the programs that we’re talking about, about the initiative programs, the diversity programs, and everything. Carol and I are both “wild childs” that came out of nowhere with no reason for anything, for us ever to rise above our station. But, somehow — with a combination of luck and initiative — we were able to do it. But there is no way either of us could have imagined that we would have had the life that we’ve been able to have. Also, the fact that we’ve been married for 47 years, which is about as unlikely as anything in Hollywood, isn’t it?

That’s an almost unbelievable Hollywood story. But I’d have to think that in order to have that longevity you either have to have a partner in life who either is completely supportive of your career or you need to have the co-dependency of you supporting her and her supporting you.

It may be anathema to say this, but I doubt very much that we would have been able to go down this path together, mutually supporting, mutually helping, mutually embracing each other in difficult times if we had decided to have a family. I think both of us knew that the responsibilities of bringing children into the world and raising them — that it would have been very hard to have had these parallel careers sustained at the level that, so we made the decision not to have children. I firmly believe that that was very instrumental in a positive way. People ask, “Why didn’t you have children?” You know, you can’t have everything. I learned very early on with some of the assistants and operators that I worked with before I became a director of photography who were Hollywood royalty — Jim Glennon, who was Bert Glennon’s son. Chuck Rosher, who was Charles Rosher’s son. They were not close to their fathers. Their fathers were absentees. Now, I’m not saying they were all like that, but you know.

I spoke with a very prominent cinematographer a few years ago whose son was getting into the business and becoming an assistant and operator. We talked a little bit about the idea of nepotism. He said, absolutely, it exists, but at the same time, a name or a call to a friend might get you through the door, but if you don’t have the talent to perform your position, you’re not going to last long.

That’s true, isn’t it? Even in the world of social media and hype, of press agents and publicists, ultimately, and sometimes even with talent, your shelf life is very short. Carol and I both had, and our generation, had the privilege that even though there was not instant gratification and you had to spend those 10 years or whatever it took to work, you had also the assurance that the journey on the way up was secure enough and the institutional memory was strong enough that the investment you were making, if you did get there, there was a likelihood that you would have a sustained career. That’s gone. The whole societal, cultural, business world now is so erratic and so based on instant messaging and social media. I think we have no idea and I don’t know at what point we will really have enough of a distance perspective on it to understand how fundamentally the way we understand ourselves and our relationships with other people and our place in the world, how much it has been compromised by the so-called social media tools that we use, which are not bringing us closer together but are making us less sensitive and less bonded, as a matter of fact, as we find out more and more.

“The entire body politic is so fragmented right now because we’re so insistent at getting personal voices through that there’s very little sense of the communal experience, of what is it that we share, what is it that gives us common ground as human beings, as Americans.”

With that in mind though, where does that put theatrical motion pictures? Because here you have an inherently communal experience and, in its essence, in your audience, you’re sharing a dream, a vision that you’re all experiencing in the same timeframe. Is that audience storytelling dynamic at odds with what’s popular today? Are we basically training people to not key into that? Or do they need that even more in order to have shared experiences?

They probably need it even more. But what I think we’re seeing, certainly in music, in the world of graphic arts, and certainly in the world of cinema and streaming movies and so forth, we are seeing more and more fragmentation. We can call it diversity and it’s great that diverse viewpoints are getting platforms to speak and identify themselves, but there is so much focus on diversity sometimes for its own diversity sake because it is different, and it’s the new throb of the beat of the moment, that we’re losing consensus. I don’t think — maybe it was illusory. Was the whole notion of, “We are Americans and we have an identity,” ever more than a fragmented, partly coalesced illusion? I don’t know. But what I do feel very strongly about now is that we’re broken apart in so many pieces that it’s really hard for us to talk to each other. We’re talking at each other. We’re talking to our own kind. This is one reason why I think the entire body politic is so fragmented right now because we’re so insistent at getting personal voices through that there’s very little sense of the communal experience, of what is it that we share, what is it that gives us common ground as human beings, as Americans. I mean, I look around me and most of what I see is divisive. I don’t think that’s just because I’m 77 years old. I don’t know. But I feel that a lot of the young people are very confused and disillusioned because they feel alone, in a way.

You’ve written so much about film history and you have a perspective on Hollywood and how things used to work. When you came into the business in the late 1960s, did you have a sense then that the studios were dying?

Yeah. I still got some sparks off of that fire, the studios’ fire. I understood it and I knew what it was. But it was done.

Do you wish you could have participated in that version of Hollywood, the classic studio system?

Absolutely not. I think that what I got was some of the best of it. I would not have wanted to have been trapped inside that system even though when I started to work, my peer group tried to work, we had to fight our way in as opposed to, during the studio system when nepotism really ruled the day. I have no nostalgia or regrets for any of that. I feel that I and Carol and our peers are very privileged in the time that we came — and we arrived at the end of the highly structured studio era, understanding it was starting to fall apart. But we understood, when I got into the ASC in 1985, a lot of the men who were on the Board of Governors here, people like Linn Dunn, people like Stanley Cortez, Phil Lathrop, who I love to death, they were all part of that time. They weren’t necessarily working anymore, but you got to know them and their values and all that. But, also, being part of an iconoclastic generation that was trying to redefine cinema was also very exciting. The interesting thing about it, we talk a lot about the revolution of the New Wave and new American cinema and all of that, but you know, the critics and the writers and those of us that were starting our careers at the time, we didn’t throw out — it wasn’t like “burn the barn down.” If you look at the New Wave critics, they were embracing artists like Raoul Walsh and Howard Hawks, people whose career went back to the Silent Era, who were still making movies. There was John Ford. Just so many of them. So, it was really the best of both possible worlds. You could feel that you were carrying the continuity of a mantle of tradition and history but you also had the freedom to move forward on your own. Because there was such chaos and all the rules were being redefined, you also had the ability, the impunity to make your own mistakes early on without being essentially castigated because everything was being questioned. I mean there’s a lot more at stake now, as we talked about very early on. A lot more at stake now for people starting off who have such a high level of expectation of themselves and the industry having such a high level of expectation of their work that if they don’t produce very early on, they get thrown into the wood pile. I don’t know. I have a great deal of sympathy for people trying to start careers today. First of all, there’s just so many more people. I mean it is just — every college campus in the country has some sort of film program now and there is so much illusion, so much — what can I say? Yeah, illusion that people are going to have careers when they’ve got no chance at all. There are a lot of movies being made, but 90 percent of them never get released.

Well, there are certainly not as many studio films being made today as there used to be. And I’m sure there’s a high percentage of them that are shot by the same small group of people. In a lot of ways, there’s a great chance of a young person playing for the NBA than getting a chance to shoot studio pictures.

Well, it’s true, almost in anything.

Can you talk a little bit about the tenacity that it takes to be successful in this business? And when I say “business,” I mean cinematography as both an art form and a business.

In terms of tenacity, endurance, perseverance — however you may want to define it — if you don’t have that, if you don’t understand that and you’re not willing to make that commitment, you should find something else to do. Because the challenges, even the obstacles, are formidable. Early on, Carol and I used to talk to film students when we’d do programs and things and talk about opportunities. I didn’t like to give career advice or anything like that, but we used to talk about it. But I can’t do it anymore. I cannot — and I’m sorry if this is all coming out negative. I don’t mean it to. But I cannot, in good conscience, talk to young people looking for careers in the film business, even when they’re still in film school and encourage them to move forward unless they fully understand the commitment that it takes. I got one piece of career advice that was probably the single best I ever got. I was a camera assistant. I did not have the seniority in the grouping system to work on a studio lot. So, I did a lot of commercials because I could work a day here, a day there and nobody could see that I was working and kick me off of a job. So, I did a lot of commercials and I worked with a lot of different people. I did a couple of commercials with Phil Lathrop, who we don’t think of as somebody who shot commercials, but he did, near the end. We were doing a car commercial one day and we had a beauty shot to do at the end of the thing. It was out in Thousand Oaks. There was a huge piece of asphalt that they had watered down so it would look dark and shiny. We were waiting for the sun to go down for that soft, wrap-around backlight to do a high-angle beauty shot of five cars from the top of a Titan crane, waiting there for the light to — it was the last shot we were going to do. I’m sitting in the assistant seat and Phil is at the Panavision, the PSR. I see he was just sitting there. I said, “Mr. Lathrop, could I ask you a question? I’m really just starting my career and I do want to be a cinematographer someday, at least I think I do. Do you have any advice you could give me?” He thought for a second, and he said, “Yeah.” He looked me right in the eye. He said, “There’s only one thing I can tell you really. Sit down whenever you can.” He’s right. That got to the quick of it. Just don’t kill yourself forging ahead all the time. Relax, sit down, look at the situations. That’s what I interpreted. This is a man who had done it all. He was, I recall, one of the camera assistant on Gone with the Wind.

Did Lathrop realize what great work he had done in his career? I first got to know his name from the amazing opening shot from Touch of Evil. But did people then have any idea of what great work they were doing?

I don’t think they did. I think they just were always moving ahead to the next project. There was very little retrospect. You’ve got to realize, this was before VHS. It was before the Z Channel or cable. It was before any kind of streaming existed. Then, suddenly, the history of movies became available for anybody. You’d see bad-duped or low-contrast prints on television that gave you no idea what the work was. So, I don’t think that they did. Phil Lathrop never talked about his work. Linn Dunn, who I knew for years on the Board here before I realized what he really had done, was very modest. The only person I knew who blew his own oversized horn was Stanley Cortez. The rest of them were all incredibly modest and not self-aggrandizing. I think one of the things that got John Alton in trouble was his posturing. He wore that French beret and a very sporty bowtie. He wrote a goddamn book about his work called Painting with Light!

“You know, you find out more about some of the cinematographers by reading the biographies or autobiographies of the directors they worked with.”

How dare he!

Exactly. Plus, Alton resigned from the ASC once and Shamroy talked him back in, then he resigned again. Some of these gentlemen were not our kind in terms of the way American cinematographers thought about or talked about themselves. The ASC was, at that time, a very closed club. I remember when I did some research on Boris Kaufman. He was nominated for On the Waterfront before he was a member. The ASC instantly reached out to him, accepted his application and he was a member within about four weeks because they were afraid — the last thing they wanted was for him to win an Academy Award and not being an ASC member. But it’s not like they embraced him or anything. I read a little bit about that. You can go back and read some of the meeting minutes, which are all in the ASC papers at the [Academy’s] Herrick Library, and you see how little love there was for some of the people who were not insiders, people like Alton and Kaufman, who stayed on the East coast and never shot a film in Hollywood. On the Waterfront was his first American film. He got nominated and won the Oscar. But there’s a whole incredible history. These guys, they each have the most amazing... because they were all very colorful and yet, as you said earlier, what do we really know about them? Because most of them did not write, or if you look at the old issues of AC magazine, most of what they wrote about was equipment or technology. You know, you find out more about some of the cinematographers by reading the biographies or autobiographies of the directors they worked with.

I’m presuming that Camerimage is screening a mini-retrospective of your pictures. Did you select the titles?

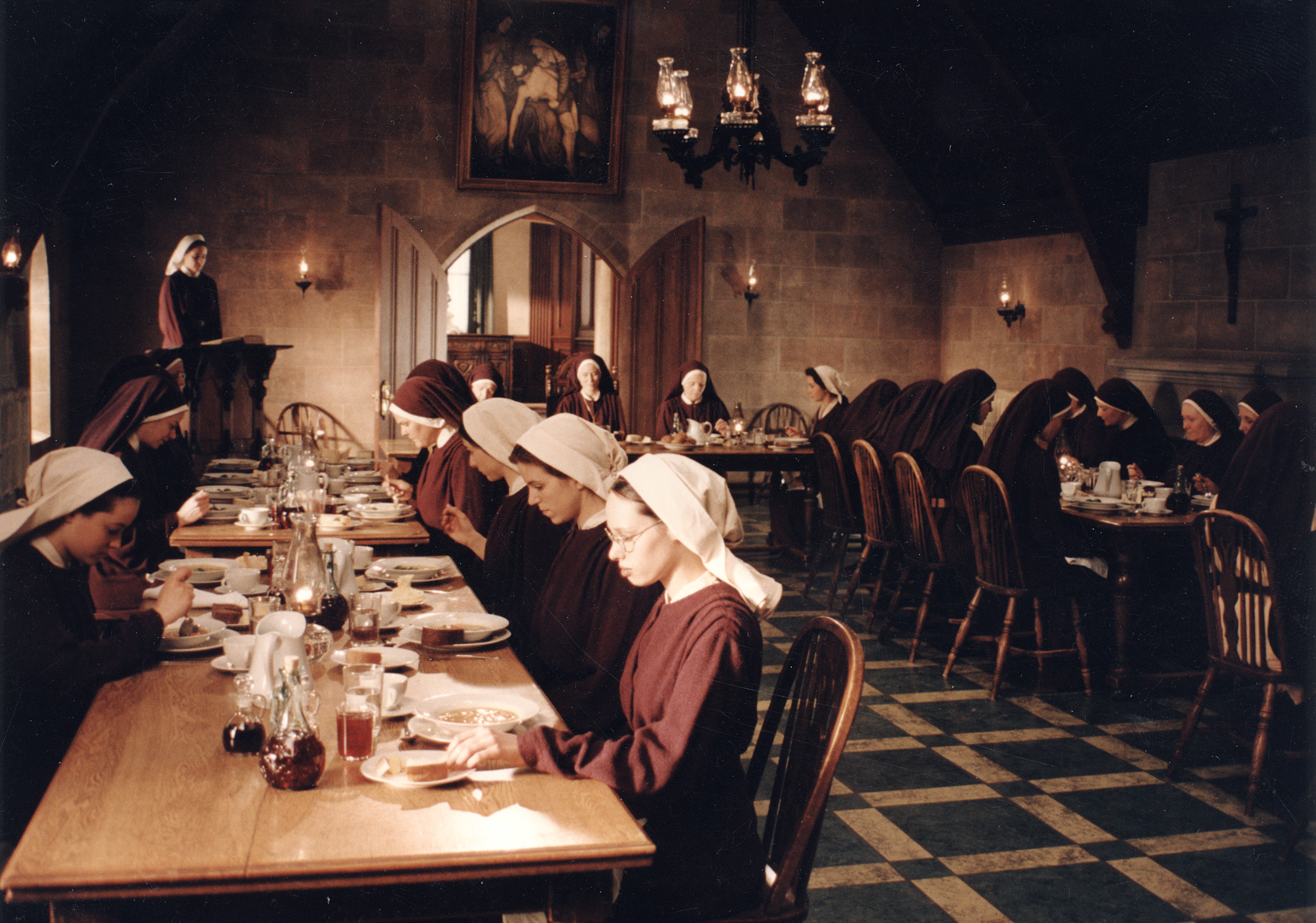

Yes. They’re really offbeat. There are a couple they wanted to show because they have — first of all, because they’ve moved back to Toruń, there are no 35mm projection facilities. So, they’ve got to run everything on DCP. So, that’s limited to a certain extent what I can do. They’re going to show American Gigolo and Ordinary People on DCP. I’ve asked them to show a couple of other films. I’m going to have a DCP of one of the last films I did that finally got a very nominal release but a film I love very much called Burn Your Maps, a film I did in Calgary with Jordan Roberts. It was a hit at the Toronto Film Festival. We all thought it was going to sell. It didn’t. It sat on a shelf unsold for three years and finally got a very small, nominal release. Well, it’s a film I love. I love the cinematography. We’re going to show that. I’m going to show a DCP of a film that I produced and directed that was never released, made in 1995. It was why I decided to no longer become — to work as a — to continue working at all as a director, even though I did a few concert films and performance films after that as a director, Mariette in Ecstasy. Paul Sarossy photographed it. I’m going to go ahead and show the DCP. It’s an orphan film. It’s never been shown publicly. It stars Geraldine O’Rawe, who’s actually married to Paul. They’re both going to be there and he’s going to be there with the new film of Atom Egoyan. So, we’re going to show Mariette and talk about it. I’m also going to show my own DVD of Incident at Loch Ness.

“That’s what I’m going to show — a film that’s never been released, a mockumentary, and a very small film that you hadn’t even heard of and then two iconic films I did back-to-back, American Gigolo and Ordinary People.”

I love that movie. It’s hilarious and says so much about filmmaking.

Yeah. I’m going to show it, even though it’ll look terrible from a DVD. It’s okay because I shot it with an old pre-HD Panasonic DVX one-third-inch chip camera. Actually, there is a 35mm print of it that the director has because we finished it on film. We made a 35mm negative and a couple 35mm prints. It was from the 35mm negative that we made the video masters, so it looked pretty good. That’s what I’m going to show — a film that’s never been released, a mockumentary, and a very small film that you hadn’t even heard of and then two iconic films I did back-to-back, American Gigolo and Ordinary People. There are lots of others I would have loved to have shown. One is a film I love very much, The Pope of Greenwich Village, but there’s really nothing that exists of it that I can easily get ahold of. It was an MGM film and trying to get anything from MGM is difficult. I would have loved to have shown Continental Divide, which is another film I love a lot.

But I’m very excited to be showing Mariette in Ecstasy. It takes place in a cloistered convent in upstate New York in 1906. It deals with a young postulant who is suffused with love for Jesus to the point of perhaps hysterical imagination or self-inflicted wounds. She starts to bleed, stigmata. Sends the convent into turmoil. It’s a metaphysical mystery. It’s with Geraldine. Rutger Hauer plays a priest. John Mahoney, Mary McDonnell and Eva Marie Saint, and about 25 or 30 young Canadian actresses who play the nuns. I mean it’s a film that I have some very good feelings, strong feelings for. I co-produced it with Frank Price, who I saw recently and helped me decide that I could go ahead and show this. He was the head of a company called Savoy Pictures. He had run Columbia and a couple other studios before that.

While we were in postproduction, Savoy went bankrupt. Mariette in Ecstasy and five or six other pictures they had got scattered to the winds. Mariette just never got released. It was so painful for me, the fact that it did not — there was no director’s cut. It was — the film, trying to save the studio and trying to save the film, make it more commercial, it got bowdlerized. I just recently came to terms with that as a compromised film. I’m going to show it. But it took me more than 20 years to come to that conclusion. Because I had a 35mm print, which I’ve given to the Academy Film Archive, they made a DCP. Yeah, that would be an interesting experience to write about because it’s a cautionary tale of a cinematographer becoming a director, especially one who is trying to make an art film in Hollywood. You know? I got beat up pretty badly.

Biographical text by Jon Silberg