Shooting a Feature on an iPhone: 5 Tips and 3 Scene Breakdowns From a Cinematographer Who Did It

Director of photography Tobias Deml shares his strategies for key scenes on Luc Besson's June and John, and his takeaways from shooting the low-budget romantic thriller on the iPhone 12 Pro Max.

Throughout my career, I've worked on many productions with limited resources.

Some of the wildest of these projects included swinging DSLRs, mounted to the longest 2'x4' beams available at Home Depot, over cliffs or out of driving cars to get fake crane shots; lighting entire interior scenes with only mirrors, because we couldn’t afford lights that would make a dent; or strapping myself with a harness onto the back of pickup trucks to get frontal shots of horses for a Western.

Still, none of these projects were ever as high-stakes as shooting a low-budget feature on an iPhone while sharing a slate with Luc Besson.

For me, our film June and John presented the ultimate challenge: Using a sensor and lens system with a very limited capacity to create a shallow depth of field for anything farther than four feet away, and a limited dynamic range that would require the utmost discipline in framing and time of day. We ended up with six iPhone 12 Pro Max bodies that were prepped and would come with Luc from Paris. Each of them had been modified by Europacorp to remove a protective glass layer that created a double specular highlight when shooting against a light source.

During prep, it became my mission to ensure we would max out what we could get in this form factor; the removal of the extra glass layer set me up in the right way. Here are five insights I can pass on to anyone crazy enough to shoot a feature film on an iPhone.

1. Mounting ND Filters

The first giveaway that tells the audience “This was shot on a phone” — aside from overzealous picture sharpening and limited dynamic range — is the high shutter speed during daytime shots, caused by the phone's optimization for proper exposure when left to its own devices. Our Moondog Labs filter mount was a quasi-cage that had been chosen back in France and turned out to be excellent; it not only allowed the attachment of some basic SmallRig handles for better camera control and more inertia in movement, but allowed me to mount proper variable ND filters to the rig. This way, I could keep my shutter speed consistently at 1/50th or 1/60th and regain cinematic motion blur throughout the film.

2. Snap-On Lenses & Magnifying Glasses

The cage also allowed for the snap-on lenses made by Moment (a brand that primarily serves influencers). Each of these lenses had relatively small front diameters, so we bought step-up filters and other solutions to fit our ND filters onto the lenses.

From my work on Hangman, a 2015 found-footage horror film I shot entirely on security cameras and camcorders, I knew of the existence of non-cinema lens extenders — magnifying glasses that were made to extend the focal range of basic camcorders and screw directly to the front of these cameras (rather than the proper cinema extenders that mount between lens and sensor). I brought two of these onto our production so we could emulate a 58mm and 85mm lens, respectively (extending our existing ~21mm and 35mm options). One caveat: The further we extended the focal range, the less the internal sensor stabilization of the iPhone worked. The final 85mm lens rig looked ridiculous, but did wonders to extend our cinematic language, and some of the most touching shots in the film were captured through these bizarre magnifying glasses.

3. Using FiLMiC Pro

At our time of filming in mid-2021, the recording app FiLMiC Pro was the most advanced app to shoot anything on an iPhone. It supported a home-baked codec called the Filmic Extreme, which offered 10 bits encoded in H265, with an as-flat-as-possible look. Researching and picking the right app — and then testing the full-color roundtrip workflow — is essential for anyone looking to film on a phone.

4. Remote Follow Focus via App

FiLMiC Pro offers a remote video and remote focus-pulling feature that has about a 0.5-1 second delay. I opted for an iPad that would allow me or my 1st AC to pull focus with my thumb — similar to how the app does it on the main phone. Other new apps might offer better looks, but having remote follow focus is practically a must for creating a feature film, so this feature is absolutely vital.

5. Aspect Ratio Tape

Filmic didn’t support aspect ratio overlays at the time, so we outfitted all phones with a thin gaff tape guide to show us the eventual 2.35:1 crop.

A Small and Scrappy Shoot

Next to shooting on the iPhone, June & John was also conceived as a micro-crew approach to filmmaking. When the producers shared with me that I would have a total crew of one person (apart from myself), I thought the email I was reading had a typo. But that’s what our crew was — Adrien Bourguignon, a talented all-rounder junior cinematographer from France, and me. Adrien would be my 1st AC, gaffer, key grip and the rest of G&E. I was the other half of the G&E and camera crew. (Some rare exceptions — one of which is detailed in my breakdown of the "Rooftop Run and Subway Meet" sequence below — called for us to bring in additional crew, for shoot days that incorporated intermittent use of digital cinema cameras.)

Outside of some documentary productions, I had never worked this small of a team, so I had to create entirely new workflows and methods of sharing duties. Luc’s preference to operate on most of his films was very helpful in this case, as I knew that I needed to execute a lot of my lighting vision on my own. It was also vital to sync up with Adrien to jump into this whirlwind with me; ultimately, the two of us would either make or break all of our visuals. Serving as our production vehicle was a Cadillac Escalade SUV with lots of trunk space, which I shared with one of our producers, Fred Imbert, who essentially became our G&E and camera-van driver.

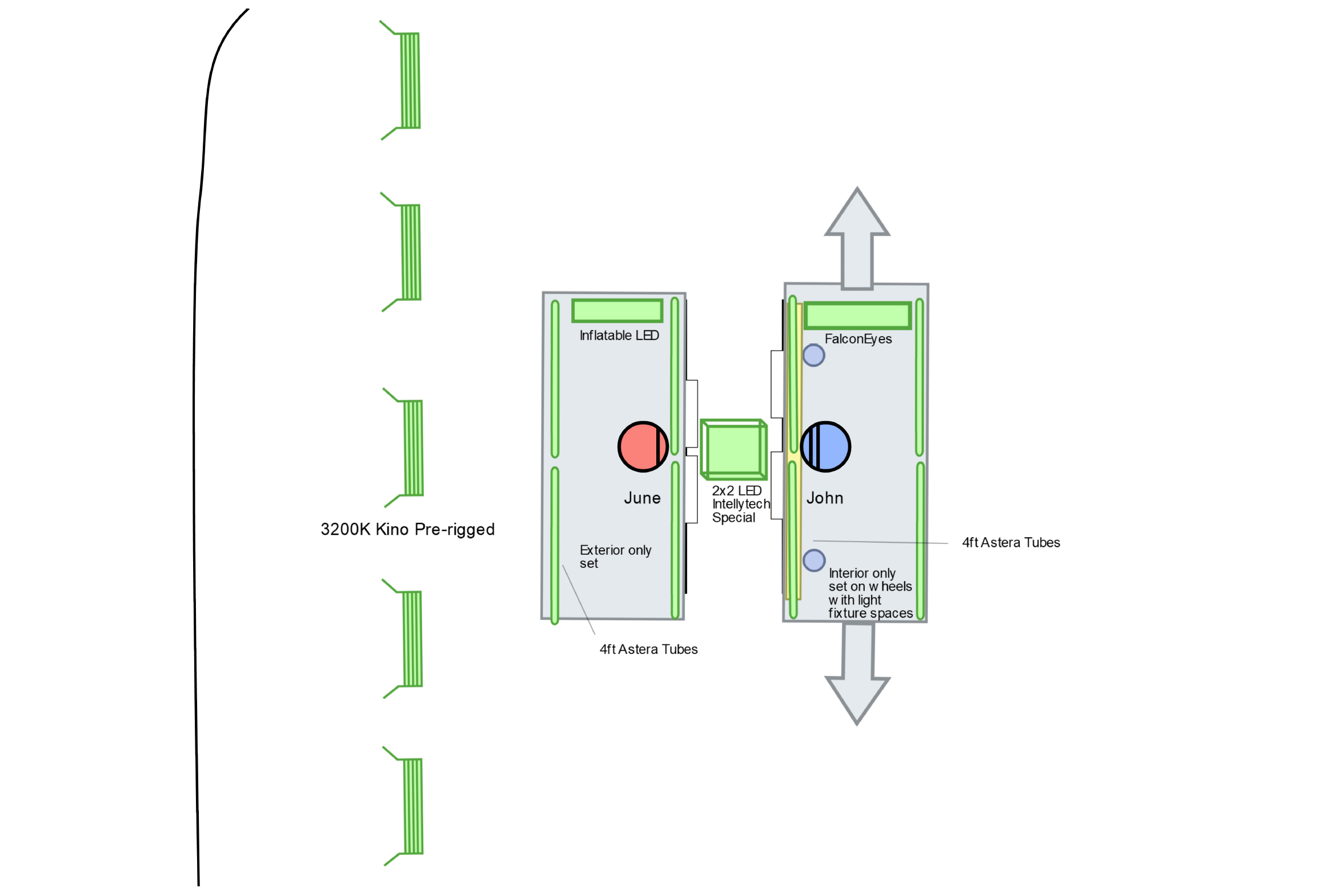

I had to optimize my lighting package to be incredibly nimble, variable in size for special days, and versatile for my core package. A 2'x2' Intellytech LiteCloth-160RGBWW 2.0 served as most of my key light; a 2'x2' Falcon Eyes RX-24TDX bicolor LED was used for some fills or second keys; and one Aputure 300D and one 600D were my second key, back or rim lights. Astera Titan Tubes and inflatable French lights came from France to supplement the package.

Once we started filming, it became obvious that everyone was willing to help each other, wear multiple hats and was happy to get their hands dirty. Sometime during lunch on until second day, I learned that our Covid PA Daniel Nunley was a photographer and aspiring cinematographer. We immediately brought him in to be our 2nd AC and G&E swing (whenever he didn’t need to attend Covid related duties), so we technically ended up having two and a half people on the G&E and camera team.

When Luc first told me about his vision to execute the film on an iPhone, I tried to talk him out of it. "We could shoot the film on another small camera, or something that can match the vision of being small and scrappy but has a better sensor and lens platform," I reasoned. But Luc was undeterred — he had envisioned the film’s production environment from the get-go as incredibly nimble, akin to an ultra-lightweight French New Wave shoot.

The more I listened to Luc, the more I felt that what he wanted to execute wasn’t one of those films that says “shot on iPhone” for mere PR purposes, yet, in practice, uses the iPhone as a sensor, and accessorizes it with a massive adapter, real cinema lenses and wireless systems. No, this would be real and raw, more like Tangerine (AC February '15; shot by Radium Cheung, HKSC) — a phone, a little cage and some magnifying glasses, that's it.

For color grading and post-processing of the iPhone footage, I worked with the Paris-based colorists Luc had chosen to set a technical foundation for the color — embracing a filmic look and shying away from the more clinical phone-video look. We experimented extensively with any approaches that might remind us of film: introducing grain, slightly softening the picture, glow, vignetting, highlight roll-off, crushing of darker areas, saturation and hue response that would be anti-digital, a modified gamma curve, color restoration in the highlights, digital halation, and an emulation of Kodak Vision3 200T-500T.

Scene Breakdown 1 — Rooftop Run/Subway Meet

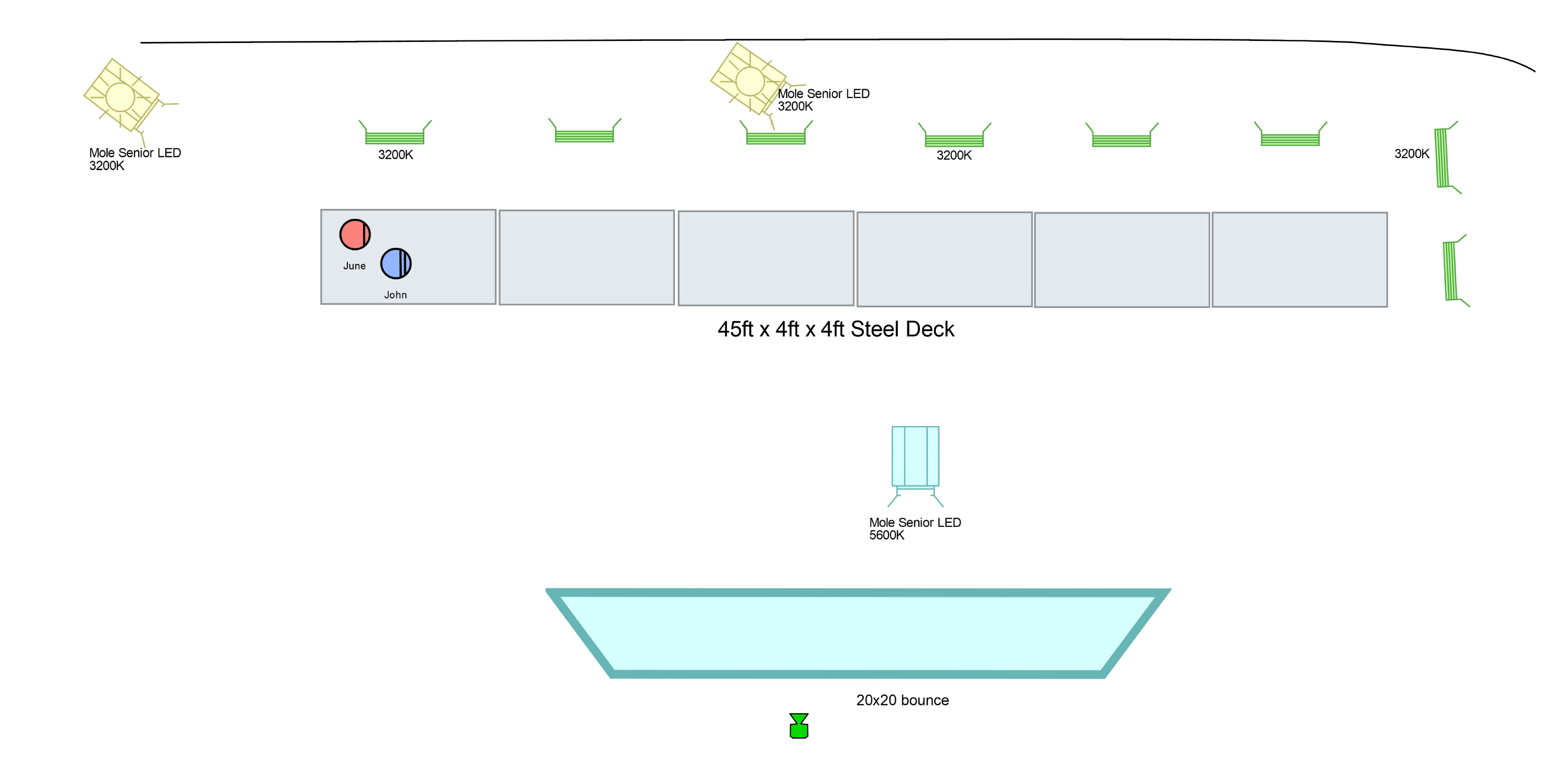

This combo scene was particularly important for the film, since we knew both parts of it would make for a great trailer sequence, and that both would be shot on the only day we used greenscreen and a high-end camera — a Blackmagic Ursa, which would allow us to capture proper chromakey — for specialty shots. Our talented and resourceful production designer, Aurélie Taillefer, constructed both a clone of a Los Angeles Metro subway car and a clone of a desert motel’s rooftop awning.

Both the subway-segment set and the motel awning looked photo-real, which made my job a lot easier; in either case, there would be no hiding of imperfections due to the deep depth of field. For our rooftop run, Luc had been planning a 60' dolly shot — one of the only days on which we had a team larger than two and a half people. This shot, captured on location, was later combined with a greenscreen composite, as the roof of the real motel was not safe to actually run on.

Scene Breakdown 2 — “I Am the Angel of the Apocalypse”

This was one of the indoor scenes for which I could truly use what little lighting gear we had and feel that it was perfectly sufficient to achieve the look we wanted. On many other scenes, I had this creeping thought of “I wish I had..." But on this one, we managed to time natural light with limited augmented artificial light perfectly.

Early on in the film, there's a moment in which June decides to rob John’s boss to get cash for her road trip. We had six characters in this scene, and we didn’t have the ability to control the sunlight outside the office with a crane or other large rig. So, we carefully scheduled our shoot time to match the right angle of incoming light. The scene happens shortly after June talks to John for the first time, so I chose to light her in a somewhat angelic fashion, more toward camera axis than I usually would.

Here are the results in two frames:

Scene Breakdown 3 — “Moving the Sun with a Finger”

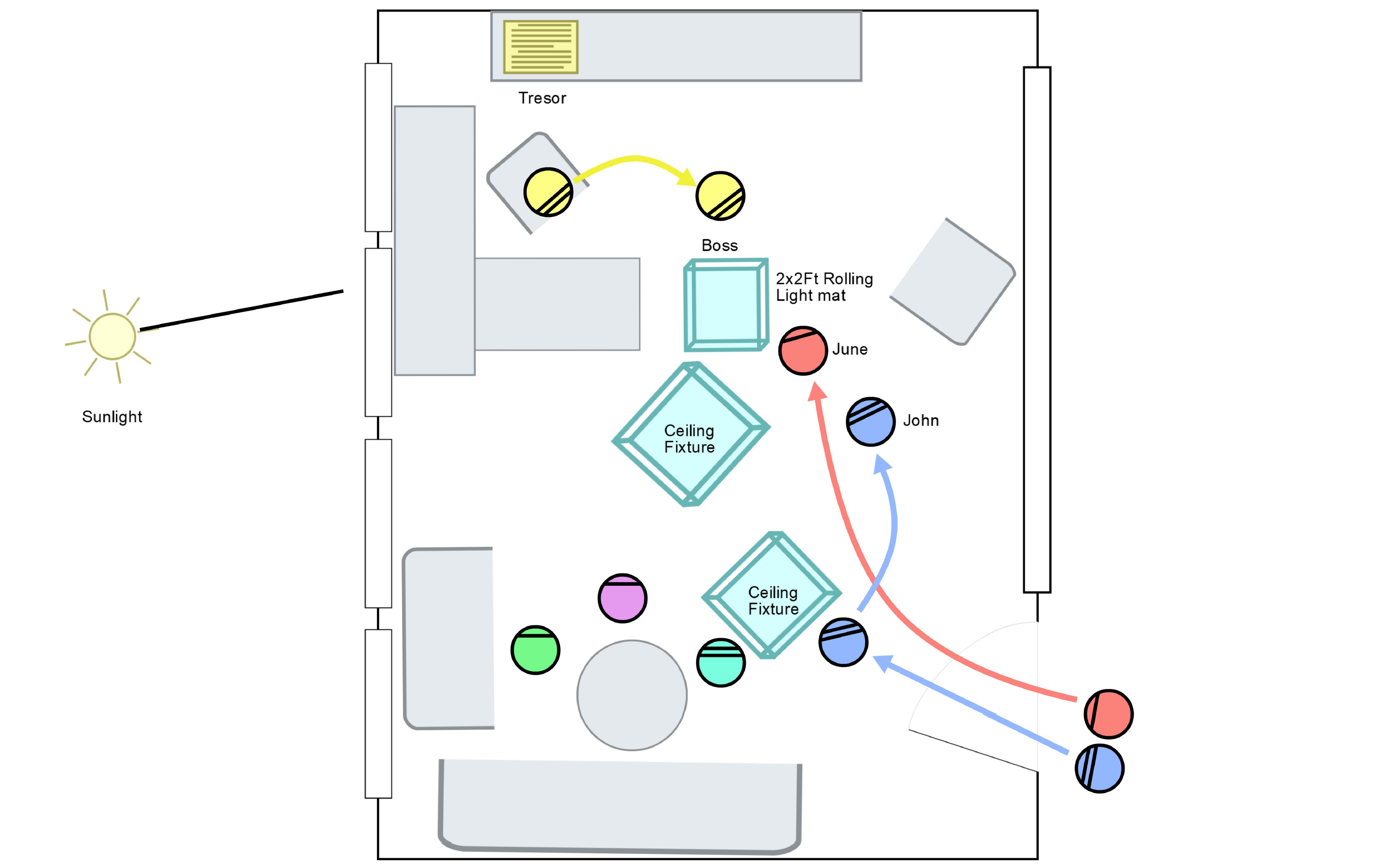

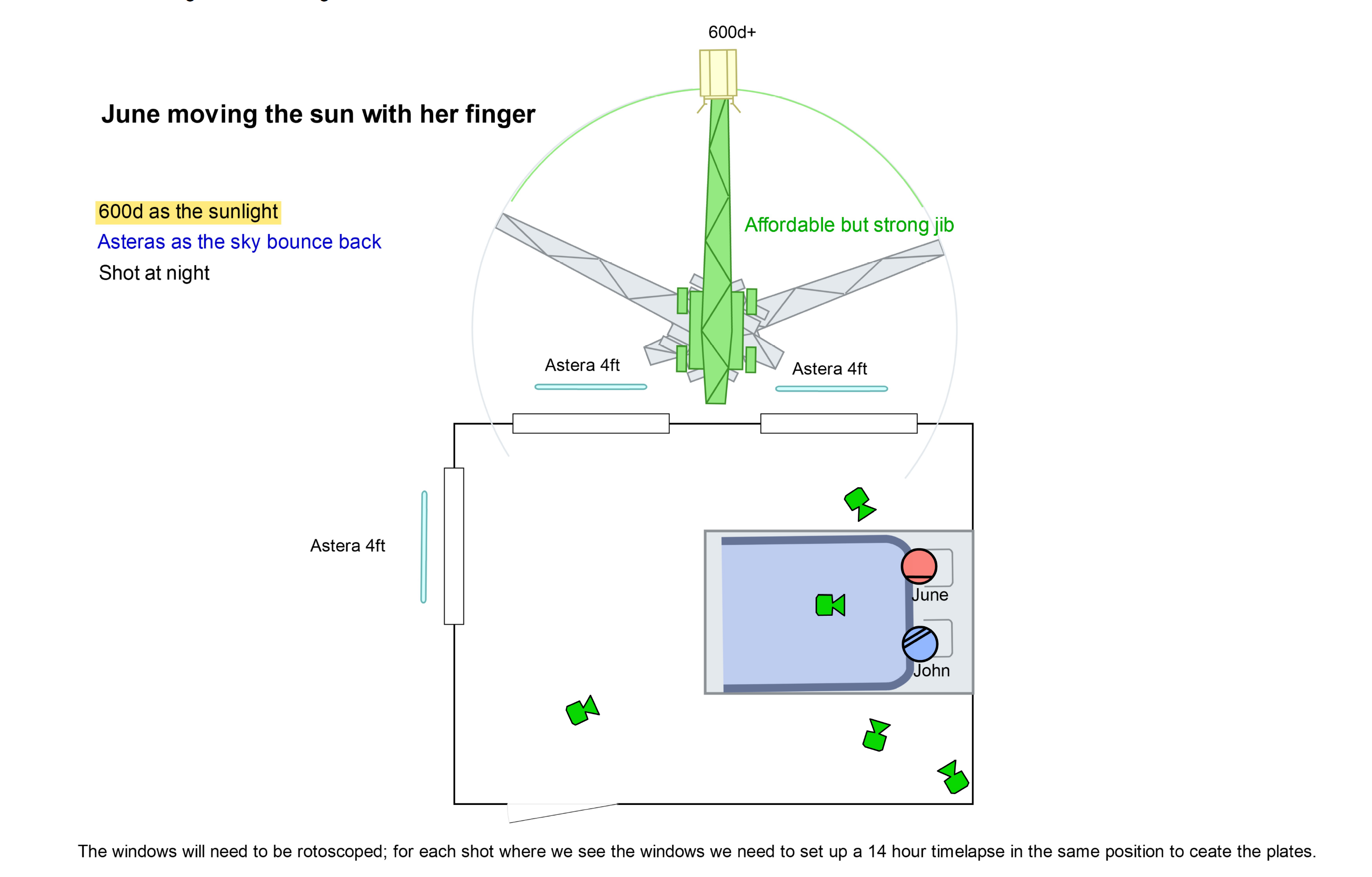

This was by far the most ambitious of all our lighting setups. Shot on the second story of a villa, the scene required the utmost attention to detail. We had one more G&E swing on the day we shot it, but the three of us still made for a very small team. The script called for June to literally move the sun with her finger, and for a 14-hour time-lapse to appear as if unfolding within a few seconds. Initially, my plan consisted of mounting our 600D onto a jib that would swing the “sunlight” across, outside the room. (See the below schematic.)

However, once we were set on the location and my gear package, we realized this was not going to happen.

"We had planned to have our 600D mounted as the moonlight on an insane rig — comprised of a Menace Arm vertically placed on top of a Mombo-Combo stand — and extend all pieces of the rig to about a 70 percent extension each, resulting in the Mombo-Combo gaining an extra 12 feet of height and reaching nearly to the third story of the villa, which is located about 25' up from ground level. But given the size of crew, it would have been insane to try to move a fixture at this height.

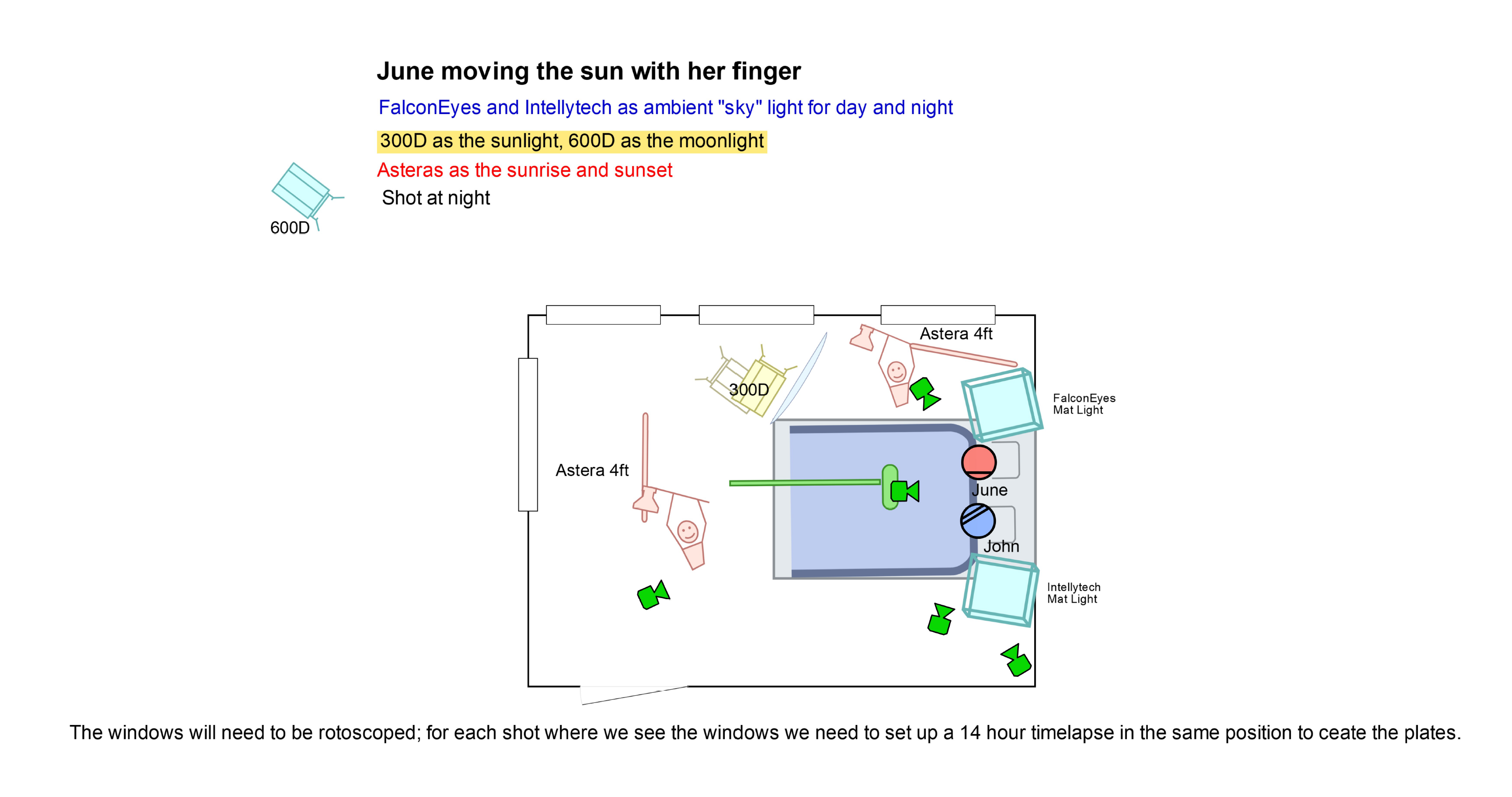

Instead, I devised a human-run gag with the help of gaffer/1st AC Bourguignon, Covid assistant/PA/swing Nunley and PA Fillippo Becciani: Two of our Asteras, placed in opposite corners of the room served as our sunrise and sunset; our Falcon Eyes and Intellytech mat lights, both bounced off of the ceiling, helped create daytime and nighttime ambient light; and our 300D, when swiveled on its mount and bounced into the ceiling, helped create a soft, "moving daylight" effect. Each of these 6 sources were then manually dimmed and/or moved in choreographed fashion, to trace the movement of the sun and the varying intensity and color of both sunlight and ambient sky/moonlight.

The foreground of this scene, which shows June and John lying in bed, was rotoscoped. We then separately recorded a timelapse of the room over the course of 14 hours, from before sunrise to sunset.

Here are some frames from the final, composited sequence — one of my favorites of the whole film: